Abstract

Backgraund

Acute-phase response proteins (APRP), cytokines and hormones have been claimed to be an independent prognostic factor of malignancies, however the basis for their association with prognosis remains unexplained. We suggest that in colon malignancies, as similar to pancreatic and lung cancers, changes in APRP are associated with angiogenesis.

Methods

C-reactive protein (CRP), albumin, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α, midkine, VEGF-A, VEGF-C, leptin, adiponectin, and ghrelin serum levels are studied in 126 colon cancer patients and 36 healthy subjects.

Results

We found statistically significant difference and correlations between two groups. We found significantly higher serum CRP, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α, VEGF-A, VEGF-C and leptin concentrations in patients relative to controls (p < 0.001). We found lower levels of the serum albumin, midkine, adiponectin and ghrelin in patients compared to control subjects (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Cachexia in patients with colon cancers is associated with changes in APRP, cytokines and hormone concentrations. These biomarkers and cachexia together have a direct relationship with accelerated angiogenesis. This may lead to a connection between the outcomes in malignancies and the biomarkers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cachexia due to cancer is one of the most frequent features of malignancy [1], it accounts up to 30-50% of cancer-related deaths in gastrointestinal tract malignancies [2]. Cachexia due to cancer is a complex metabolic disorder, including loss of adipose tissue due to lipolysis, loss of skeletal muscle mass, elevation of resting energy consumption, anorexia, and reduction of oral food intake [3, 4].

Despite intensive studies that have been conducted thus far in this field, the multi-factorial pathological mechanism of cancer-related cachexia has not been fully exhibited, besides currently available treatment modalities remain profoundly unsatisfactory [5]. Nevertheless, it is well known that cytokine up-regulation contributes to involuntary weight loss, which is a hallmark of cancer-related cachexia [6, 7]. Although the catabolism is mainly mediated by the effects of certain cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) [4, 8], the mechanisms associated with cancer related anorexia are still not elucidated completely [9]. Previous studies concerning cachexia in gastrointestinal cancer revealed that other pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-8 and, probably, vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A) and midkine, might be involved in the process of cachexia [10]. Also, the proteins such as cytokines, some hormones and neuropeptides, which affect various central mechanisms, are tightly related to the regulation of the energy homeostasis [11]. These hormones include adiponectin, ghrelin, and leptin [11, 12].

Adiponectin is a member of a group of proteins secreted from adipocytes [13] and its serum levels are (5-30 μg/ml) higher in women compared with men [14–16]. Adiponectin serum levels inversely correlate to body weight. Thus, low adiponectin levels are found in obesity [14, 15], and high levels are found in anorexia nervosa [16] and during weight loss [17]. Several reports have indicated association between low adiponectin levels and increased risk of breast, endometrium, and gastric cancers [18–20]. The mechanisms responsible for regulation of adiponectin levels have not been fully elucidated. Yet, recent data suggest down-regulation of adiponectin by TNF-α, as well as by insulin [21]. The hormone ghrelin is a 28 amino-acid peptide, unique by the esterification of its third serine residue by n-octanoic acid [22]. The major source of ghrelin is the stomach, where it is synthesized in identical endocrine cells. The peptide is a potent inducer of growth hormone (GH) release, acting at the pituitary and hypothalamic levels [23].

Ghrelin participates directly in hypothalamic regulation of nutrition, it causes weight gain by reducing food utilization, increasing food intake, and inhibiting leptin-induced feeding reduction [24]. High ghrelin levels are associated with various cachectic states, such as anorexia nervosa and severe congestive heart failure [25]. Elevated levels were recently reported in lung cancer-induced cachexia [26], and in a cohort of male patients with mainly lung and prostate cancer [27].

Leptin is another member of the adipo-cytokines family. It is produced mainly by differentiated adipocytes and acts in the central nervous system as a suppresser for food intake and stimulator of energy consumption [12]. Leptin plasma levels are reported to be higher in anorexia nervosa patients [28], but lower in gastrointestinal [29], and pancreatic cancer patients [30]. Association between acute-phase response proteins (APRPs) and weight loss in cancer-related cachexia has been reported only in pancreatic carcinoma and melanoma [31].

The aim of our study was to evaluate associations between cachexia due to weight loss and APRPs (albumin, C-reactive protein (CRP)), cytokines (IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, IL-8, VEGF-A, VEGF-C), midkine and hormones (adiponectin, leptin and ghrelin) in a population of newly diagnosed colon cancer patients.

Materials and methods

Patients

A total of 126 patients with colon cancer were enrolled in our study. Exclusion criterias included: previous treatment with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or a major operation history 6 months before recovery; brain metastasis; second malignancy; acute or chronic infections; dysphagia; other primary cachectic states (i.e. congestive pulmonary disease, cirrhosis); elevated bilirubin or liver enzymes (> 2 of the upper normal reference value); renal failure (creatinine > 2 mg/dl); history of eating disorders; or gastrectomy.

Demographic clinical and anthropometric data were collected during recovery period. All pathology reports were reviewed, and data of the tumor histology were recorded. Stage was defined according to the 1997 American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging System [32].

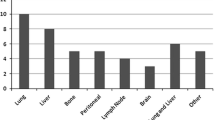

We examined 41 cases of stage II cancers, 48 cases of stage III, 37 cases of stage IV cancers. There were 54 females and 72 males, with a median age of 56 years (range 38-74 years). We used sera from blood donors considered healthy on the basis of routine blood tests to obtain reference values in this study. The reference group consisted of 38 individuals, 16 females and 22 males, with a median age of 41 years (range 37-71 years).

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height (m2), and cachexia was defined as ≥ 5% reduction in BMI at the time of recovery. The study protocol was approved by the medical Ethics Committee of Haseki Education and Research Hospital, Istanbul, and was in accordance with the ethical standards formulated in the Helsinki Declaration of 1975. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Analytical Methods

The concentrations of all parameters in the examined samples were measured in sera obtained from blood drawn in the fasting state, clotted (15 min, room temperature) and centrifuged (15 min, 1000 g). The serum samples were then immediately frozen at -80°C until further analysis (except albumin, CRP, and midkine).

The albumin concentrations were measured colorimetrically as a complex of albumin with bromocresol blue dye under acidic conditions. High-sensitive CRP was determined by the immunonephelometry (Behring Nephelometer II). Serum midkine concentrations were assayed with indirect ELISA R&D Systems, USA) anti-human midkine polyclonal antibodies were used. The serum concentrations of IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α were assayed using a validated commercial ELISA (Quantikine R&D Systems, Mineapolis). The IL-10 levels were measured by using the Endogen Inc. assay (Cambridge). The concentrations of VEGF-A and VEGF-C were measured in duplicate with a commercially available quantitative sandwich enzyme immunassay kit (R&D Systems, USA). Adiponectin, ghrelin and leptin concentrations were determined using radioimmunassay kits (Linco Research, St. Charles, Missouri).

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as means ± SD. Comparisons were performed with the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test for continuous variables and with the χ2 test for categorical data. Differences between groups were determined using the log-rank test. Two-sided p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

There were no differences of median age between patients with cancer and subjects in control group (p > 0.05). None of the parameters showed significant difference when they were compared by age between those groups (p > 0.05). Plasma leptin levels showed no significant difference between genders (p > 0.05).

We found significantly higher serum CRP, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α, VEGF-A, VEGF-C and leptin concentrations in patients relative to controls (p < 0.001). We found lower levels of the serum albumin, midkine, adiponectin and ghrelin in patients compared to control subjects (p < 0.001).

We found favourable correlation between BMI loss and adiponectin levels (p < 0.01, r = 0.74). Also, we found positive correlation between midkine and albumin; similarly between both BMI loss and plasma leptin levels; and BMI loss and midkine.

There was significantly positive correlation between BMI loss and VEGF-A; as well as VEGF-A and IL-1.

VEGF-A and IL-6 correlation was similarly statistically significant; we also found favourable correlation between adiponectin and BMI loss.

(respectively; p < 0.01, r = 0.58; p < 0.001, r = 0.69, p < 0.01, r = 0.69; p < 0.01, r = 0.71; p < 0.01, r = 0.65, p < 0.001, r = 0.73; p < 0.01, r = 0.61). The Concentrations of all parameters in patients and controls were shown in table 1.

Discussion

In our study, we analyzed the associations between acute-phase response cytokines, pro-inflammatory cytokines, cytokines, hormones and cancer related cachexia in a population of newly diagnosed or newly recurrent, untreated colon cancer. Systemic inflammation is a non specific process of many cancer types. Association between acute-phase related proteins and accelerated weight loss has been described only in a few cancer types; which are pancreatic, lung cancers and melanoma [31]. Decreased albumin concentrations are involved with cachexia and are a common laboratuary feature in gastrointestinal cancers. Hypoalbuminemia has recently been demonstrated to be a predictive factor of poor responsiveness [33, 34]. Our results showing a weight-loss dependent association with cachexia may support the association of hypoalbuminemia and cachexia. The decrease in transferring concentrations seems to be especially weight-loss dependent. The ongoing systemic imflammatory response determined in terms of CRP concentrations has recently gained some interest, as an-easy-to measure and well-standardized outcome predictor [35, 36]. Similar to substantial weight loss [10], an elevation in CRP concentration has been related to increased extent of primary tumor and has been associated with poor survival [35, 36]. Our results may support the association of CRP concentrations and cancer related cachexia. The association of CRP with the pro-angiogenic environment may contribute to adverse effects together with CRP elevation [37]. Our results reveal a positive correlation between CRP and circulating IL-8, midkine, which both have pro-angiogenic properties [38]. Similarly CRP and VEGF correlation has been determined and these results may further support this hypothesis. It is also of interest that similar to CRP [35, 36], circulating midkine [10] and IL-8 [39] have been found to reflect lymph node involvement in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. The concentrations of circulating IL-6 and midkine, independently of the patients weight status, and with Il-1, Il-8 and VEGF in cachectic cancer patients. TNF-α, IL-1 and IL-6 are key cytokines involved in cancer-related cachexia. However, apart from IL-6, alterations in their systemic levels are rarely detected [31]. As experimental cytokine-directed anti-cachectic therapies yielded moderate results [31], there is a need for finding other mediators of cancer cachexia [5, 31]. We found midkine and VEGF to be independent predictors of weight loss in patients with colon cancer. Our results provide evidence for an association of midkine and VEGF with systemic inflammation and malnutrition, supporting a possible involvement of these cytokines in the pathogenesis of cachexia. However, only the concentrations of VEGF, and leptin but not midkine, are associated with weight loss in the examined cohort of cancer patients. Midkine was related to inflammation and was correlated with albumin concentration, while the associations were not affected by cachexia. These together may further indicate VEGF as rather a pro-cachectic cytokine, corroborating the findings of other authors demonstrating VEGF associations with standard pro-cachectic cytokines. IL-1 and IL-6 have been implicated in the regulation of VEGF expression [40], while anti-TNF α treatment (infliximab) has been shown to decrease serum VEGF concentrations [41]. We found that VEGF correlated with IL-1 and IL-6 exclusively in cachectic colon cancer patiens. Although the involvement of midkine in inflammation is well-documented [42], only a weak correlation between midkine and CRP in cancer patients has been reported [43].

Adiponectin levels are reported to be inversely correlated with body weight. Thus, voluntary weight loss, as well as anorexia nervosa, is associated with elevated adiponectin levels [14, 17, 44]. However, in our study, we found no correlation between decreased BMI and adiponectin levels. Adiponectin levels are regulated mainly by changes in the adipose tissue [44]. The lack of association between adiponectin levels and weight loss may simply reflect the preservation of adipose tissue. Recent studies, which found inhibition of adiponectin secretion from adipocytes by various cytokines, including TNF-α, support our observations [21, 45]. Thus, the lack of elevation of adiponectin levels after cancer related cachexia, may reflect altered regulation of adiponectin in this condition. Interestingly, lower adiponectin levels were also found in a cohort of cachectic patients with very advanced stage of lung cancer compared with healthy volunteers [46].

Elevated levels of total or active ghrelin in cancer related cachexia have been reported in cohorts of mainly male lung cancer patients [26].

In our study, we report elevated ghrelin levels in a cohort of colon cancer patients. Notably, high levels of ghrelin were also found among a significant number of cachectic lung cancer patients [26]. Our results suggest that measurement of ghrelin levels may have important clinical implications in treating cancer related cachexia syndrome. Although leptin levels are directly associated with weight loss after fasting [47], associations between leptin levels and cancer related cachexia are not yet fully elucidated. Thus, lower leptin levels were found in patients with gastrointestinal cancers, regardless of the degree of weight loss [48]. However, association between leptin levels and weight loss was noted in a cohort of lung [49], and pancreatic cancer patients [29]. We also found a correlation between leptin levels and cancer-induced weight loss. Our results showing a weight-loss dependent association with cachexia may support the association of leptin with cachexia. Moreover, leptin levels have positive correlation with IL-6 levels and CRP in our study. This situation may explain high IL-6 levels related with cancer progression and invasion. Pyrogenic activity of this proinflammatory cytokine may responsible for cachexia and weight loss. In addition, IL-6 stimulates to the synthesis of APRP. So, adiponectin, ghrelin and leptin levels accelerated by APRP levels. Association with between weight loss and levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, cytokins, APRP, adiponectin, ghrelin and leptin leves have not been explained yet. We suggested that adiponectin, ghrelin and leptin are tightly regulated the energy homeostasis such as cytokines, which affect various central mechanisms [11]. Our study revealed an association between cytokine and pro-inflammatory cell concentrations and APRP in patients with colon cancer. In our study, there is an association between these parameters and levels of these hormones, which confirm our hypothesis.

In conclusion, our results provide evidence for an association between colon cancer related cachexia and changes in the concentrations of APRPs, cytokines and hormones. More studies should be performed to confirm this association between cachexia and APRP, cytokines, and hormones in patients with colon cancer, as well as in other cancer types.

References

Loberg RD, Bradley DA, Tomlins SA, Chinnaiyan AM, Pienta KJ: The lethal phenotype of cancer: the molecular basis of death due to malignancy. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007, 57: 225 241-10.3322/canjclin.57.4.225.

Polesty JA, Dudrick SJ: What we have learned about cachexia in gastrointestinalcancer. Dig Dis. 2003, 21: 198-213. 10.1159/000073337.

Chamberlain JS: Cachexia in cancer-zeroing in onmyosin. N Engl J Med. 2004, 351: 2124-2125. 10.1056/NEJMcibr042889.

Rubin H: Cancer cachexia: its correlations andcauses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003, 100: 5384-5389. 10.1073/pnas.0931260100.

Boddeart MS, Gerritsen WR, Pinedo HM: On our own way to targeted therapy for cachexia incancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 2006, 18: 335-340. 10.1097/01.cco.0000228738.85626.ac.

Saini A, Al-Shants N, Stework CE: Waste management cytokines growth factors and cachexia. Cytokine Growth factor Rev. 2006, 17: 475-486. 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2006.09.006.

Deans C, Wigmore SJ: Systemic inflammation, cachexia and prognosis in patients with cancer. Curr Opin Clin Nutr metab care. 2005, 8: 265-269. 10.1097/01.mco.0000165004.93707.88.

Acharyya S, Ladner KJ, Nelsen LL, Damrauer J, Reiser PJ, Swoap S, Guttridge DC: Cancer cachexia is regulated by selective targeting of skeletal muscle geneproducts. J Clin Invest. 2004, 114: 370-8.

Ramas EJ, Suzuki S, Marks D, Inui A, Asakawa A, Meguid MM: Cancer anorexia-cachexia syndrome: cytokines and neuropeptides. Curr Opin Nutr Metab care. 2004, 7: 427-434. 10.1097/01.mco.0000134363.53782.cb.

Krzystek-Korpacka M, Matusiewicz M, Diakowska D, Grabowski K, Blachut K, Kustrzeba-Wojcicka I, Banas T: Impact of weight loss on circulating IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, VEGF-A, VEGF-C and midkine in gastroesophageal cancerpatients. Clin Biochem. 2007, 40: 1353-1360. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2007.07.013.

Have PJ: Peripheral signals conveying metabolic information to the brain: short-term and long-term regulation of food intake and energy homeostasis. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2001, 226: 963-977.

Meier U, Gressner AM: Endocrine regulation of energy metabolism: review of pathobiochemical and clinical chemical aspects of leptin, ghrelin, adiponectin andresistin. Clin Chem. 2004, 50: 1511-1525. 10.1373/clinchem.2004.032482.

Diez JJ, Iglesias P: The role of the novel adipocyte-derived hormone adiponectin in humandisease. Eur J Endocrinol. 2003, 148: 293-300. 10.1530/eje.0.1480293.

Arita Y, Kihara S, Ouchi N, Takahashi M, Maeda K, Miyagawa J, Hotta K, Shimomura I, Nakamura T, Miyaoka K, Kuriyama H, Nishida M, Yamashita S, Okubo K, Matsubara K, Muraguchi M, Ohmoto Y, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y: Paradoxical decrease of on adipose-specific protein, adiponectin, inobesity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999, 257: 79-83. 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0255.

Staiger H, Tschritter O, Machann J, Thamer C, Fritsche A, Maerker E, Schick F, Häring HU, Stumvoll M: Relationship of serum adiponectin and leptin concentrations with body fat distribution inhumans. Obes Res. 2003, 11: 368-72. 10.1038/oby.2003.48.

Pannacciulli N, Vettor R, Milan G, Granzotto M, Catucci A, Federspil G, De Giacomo P, Giorgino R, De Pergola G: Anorexia nervosa is characterized by increased adiponectin plasma levels and reduced non-oxidative glucosemetabolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003, 88: 1748-1752. 10.1210/jc.2002-021215.

Yang WS, Lee WJ, Funahashi T, Tanaka S, Matsuzawa Y, Chao CL, Chen CL, Tai TY, Chuang LM: Weight reduction increases plasma levels of an adipose-derived anti-inflammatory protein, adiponectin. J Clin Endocrinol metab. 2001, 86: 3815-19. 10.1210/jc.86.8.3815.

Dal Maso L, Augustin LS, Karalis A, Talamini R, Franceschi S, Trichopoulos D, antzoros CS, La Vecchia C: Circulation adiponectin and endometrial cancerrisk. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004, 89: 1160-1163. 10.1210/jc.2003-031716.

Miyoshi Y, Funahashi T, Kihara S, Taguchi T, Tamaki Y, Matsuzawa Y, Noguchi S: Association of serum adiponectin levels with breast cancerrisk. Clin Cancer Res. 2003, 9: 5699-5704.

Ishikawa M, Kitayoma J, Kazoma S, Hiramatsu T, Hatano K, Nagawa H: Plasma adiponectin and gastriccancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005, 11: 466-472. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1453.

Wang B, Jenkins JR, Trayhurn P: Expression and secretion of inflammation-related adipokines by human adipocytes differentiated in culture: Integrated response to TNF-α. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005, 288: E731-E740. 10.1152/ajpendo.00475.2004.

Kojima M, Hosoda H, Date Y, Nakazato M, Matsuo H, Kangawa K: Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide fromstomach. Nature. 1999, 402: 656-660. 10.1038/45230.

Takaya K, Ariyasu H, Kanamoto N, Iwakura H, Yoshimoto A, Harada M, Mori K, Komatsu Y, Usui T, Shimatsu A, Ogawa Y, Hosoda K, Akamizu T, Kojima M, Kangawa K, Nakao K: Ghrelin strongly stimulates growth hormone release inhumans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000, 85: 4908-11. 10.1210/jc.85.12.4908.

Nakazato M, Murakami N, Date Y, Kojima M, Matsuo H, Kangawa K, Matsukura S: A role for ghrelin in the central regulation of feeding. Nature. 2001, 409: 194-8. 10.1038/35051587.

Otto B, Cuntz U, Fruehauf E, Wawarta R, Folwaczny C, Riepl RL, Heiman ML, Lehnert P, Fichter M, Tschöp M: Weight gain decreases elevated plasma ghrelin concentrations of patients with an anorexianervosa. Eur J Endocrinol. 2001, 145: 669-73. 10.1530/eje.0.1450669.

Shimizu Y, Nagaya N, Isobe T, Imazu M, Okumura H, Hosoda H, Kojima M, Kangawa K, Kohno N: Increased plasma ghrelin levels in lung cancercachexia. Clin Cancer Res. 2003, 9: 774-8.

Garcia JM, Garcia-Toyza M, Hijazi RA, Taffet G, Epner D, Mann D, Smith RG, Cunningham GR, Marcelli M: Active ghrelin levels and active/total ghrelin ratio in cancer-inducedcachexia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005, 90: 2920-2926. 10.1210/jc.2004-1788.

Brichard SM, Delporte MI, Lambert M: Adipocytokines in cachexia nervosa: a review focusing on leptin and adiponectin. Horm Metab res. 2003, 35: 337-342. 10.1055/s-2003-41353.

Brown DR, Beikowitz DE, Breslow MJ: Weight loss is not associated with hyperleptinemia in humans with pancreaticcancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001, 86: 162-166. 10.1210/jc.86.1.162.

Bolukbas FF, Kılıc H, Bolukbas C, Gumus M, Horoz M, Turhal NS, Kavakli B: Serum leptin concentration and advanced gastrointestinal cancers: a case controlled study. BMC Cancer. 2004, 4: 29-10.1186/1471-2407-4-29.

Lelbach A, Muzes G, Feher J: Current perspectives of catabolic mediators of cancer cachexia. Med Sci Monit. 2007, 13: RA168-173.

Fleming JD, Cooper JS, Henson DE: American Joint Committee on Cancer Staing Manual. 1997, Philadelphia: Lippincott. Raven, 5

Sanz R, Ovejero VJ, Gonzalez JJ: Mortality risk scales in esophagoctomy for cancer: their usefulness in preoperative patientselection. Hepatogastroenterology. 2006, 53: 869-873.

Oñate-Ocaña LF, Aiello-Crocifoglio V, Gallardo-Rincón D, Herrera-Goepfert R, Brom-Valladares R, Carrillo JF, Cervera E, Mohar-Betancourt A: Serum albumin as a significant prognostic factor for patients with gastriccarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007, 14: 381-389. 10.1245/s10434-006-9093-x.

Gockel I, Dirksen K, Messow CM, Iunginger T: Significance of preoperative C-reactive protein as a parameter of the perioperative course and long-term prognosis in squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. World J Gastroenterol. 2006, 12 (37): 46-50.

Nozoe T, Saeki H, Sugimachi K: Significance of preoperative elevation of serum C-reactive protein as an indicator of prognosis in esophagealcarcinoma. Am J Surg. 2001, 182: 197-201. 10.1016/S0002-9610(01)00684-5.

Crumley AB, McMillan DC, McKernan M, Going JJ, Shearer CJ, Stuart RC: An elevated C-reactive protein concentration, prior to surgery, predicts poor cancer-specific survival in patients undergoing resection for gastro-esophagealcancer. Br J Cancer. 2006, 94: 1568-71.

Beecken WD, Kramer W, Jonas D: New molecular mediators in tumorangiogenesis. J Cell Mol Med. 2000, 4: 262-269. 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2000.tb00125.x.

Krzystek-Korpacka M, Matusiewicz M, Diakowska D, Grabowski K, Blachut K, Konieczny D, Kustrzeba-Wojcicka I, Terlecki G, Banas T: Elevation of circulating IL-8 is related to lymph node and distant metastases in esophageal squamous cell carcinomas-implication for clinical evaluation of cancer patient. Cytokine. 2008, 3: 232-9.

Boedefeld WM, Bland KI, Heslin MJ: Recent insights into angiogenesis, apoptosis, invasion and metastasis in colorectal carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003, 10: 839-851. 10.1245/ASO.2003.02.021.

Macías I, García-Pérez S, Ruiz-Tudela M, Medina F, Chozas N, Girón-González JA: Modification of pro-and anti-inflammatory cytokines and vascular-related molecules by tumor necrosis factor-α blockade in patients with rheumatoidarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2005, 32: 2102-8.

Muramatsu T: Midkine and pleiotrophin: two related proteins involved in development, survival, inflammation andtumorigenesis. J Biochem. 2002, 132: 359-371.

Ikematsu S, Yano A, Aridome K, Kikuchi M, Kumai H, Nagano H: Serum midkine levels are increased in patients with various type ofcarcinomas. Br J Cancer. 2000, 83: 701-706. 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1339.

Berg AH, Combs TP, Scherer PE: ACRP30/adiponectin: an adipokine regulating glucose and lipidmetabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2002, 13: 84-89. 10.1016/S1043-2760(01)00524-0.

Bruun JM, Lihn AS, Verdich C, Pedersen SB, Toubro S, Astrup A, Richelsen B: Regulation of adiponectin by adipose tissue-derived cytokines: in vivo and in vitro investigations in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003, 285: E527-E533.

Jamieson NB, Brown DJ, Michael Wallace A, McMillan DC: Adiponectin and the systemic inflammatory response in weight-losing patients with nonsmall cell lungcancer. Cytokine. 2004, 27: 90-92. 10.1016/j.cyto.2004.03.017.

Wolfe BE, Jimerson DC, Orlova C, Mantzoros CS: Effect of dieting on plasma leptin receptor, adiponectin and resistin levels in healthy volunteers. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2004, 61: 332-338. 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2004.02101.x.

Dulger H, Alici S, Sekeroglu MR, Erkog R, Ozbek H, Noyan T, Yavuz M: Serum levels of leptin and proinflammatory cytokines in patients with gastrointestinalcancer. Int J Clin Pract. 2004, 58: 545-549. 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2004.00149.x.

Simons JP, Schols AM, Campfield LA, Wouters EF, Sanis WH: Plasma concentration of total leptin and human lung-cancer-associated cachexia. Clin Sci (Lond). 1997, 93: 273-277.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

OK, ST- Collected data and wrote the manuscript in draft. ASK- Carried out the biochemical analysis. SP-Carried out the statistical analysis. AS, ACD, IH and BD- Took part in and contributed the discussion. All authors have read and approve of the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kemik, O., Sumer, A., Kemik, A.S. et al. The relationship among acute-phase response proteins, cytokines and hormones in cachectic patients with colon cancer. World J Surg Onc 8, 85 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7819-8-85

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7819-8-85