Abstract

Background

Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma (NCMH) is an extremely rare benign tumor, primarily diagnosed in young infants and children and it often simulates malignant tumors on imaging.

Case presentation

We present computerized tomography and magnetic resonance imaging findings of two nasal chondromesenchymal hamartomas in a 5-year-old boy and a 6-week-old girl.

Conclusions

NCMH is a rare, benign tumor-like lesion with good biologic behavior. No recurrence after complete resection or malignant transformation of NCMH has been reported. A correct diagnosis is imperative to avoid unnecessary adjuvant therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma (NCMH) is a rare, relatively newly discovered, pediatric tumor. In 1998, McDermott et al. [1] were the first to use the term NCMH to describe a tumor consisting mainly of chondroid or cartilaginous tissues and mesenchymal elements that occurred in the nasal cavity and had similar morphology to chest wall mesenchymal hamartoma occurring exclusively in infancy. Reported cases have occurred mostly in infants and young children, with characteristic histopathological features similar to chest wall mesenchymal hamartoma in infancy [1–5]. However, the affected age range can vary from newborn to the very elderly [1, 6–11].

To the best of our knowledge, NCMH has been reported in less than 25 cases in the English medical literature [11, 12]; thus, the pathogenesis of NCMH remains poorly understood. In this paper, we present computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings of NCMH in two young children.

Case presentation

Case 1

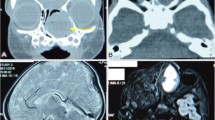

A 5-year-old boy was admitted to our hospital for evaluation of nasal obstruction, recurrent sinusitis, and noisy breathing over a period of 4 years. The child had normal nutrition and development. Physical examination revealed a smooth, purple, non-tender mass attached to the roof of the right nasal cavity. No palpable cervical lymphadenopathy was identified. The remainder of his medical and family history was unremarkable. A CT scan revealed an oval-shaped, well-defined homogeneous soft-tissue mass in the right nasal cavity. The mass measured 2.5 × 3.6 × 4.3 cm and involved the ethmoid sinus, extending up to the cribriform plate and the anterior cranial fossa with evidence of bony erosion of the cribriform plate. Tumor density was measured in regions of interest in different slices and ranged from 33 to 36 Hounsfield Units (HU) before contrast injection; it was strikingly enhanced after injection, to a range of 64 to 69 HU (Figure 1). MRI demonstrated a well-demarcated homogeneous mass extending to the anterior cranial fossa in the right nasal cavity. The mass had low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and mixed high signal intensity on T2-weighted images, with striking inhomogeneous enhancement (Figure 2). No calcification, cystic component, or definite dural enhancement was identified. The right nasal cavity was dilated. The middle and inferior turbinates were medially compressed and the nasal septum was deviated to the left, but the mass did not invade adjacent structures. A biopsy was performed and the pathology report was consistent with NCMH. Operative findings revealed a well-defined mass attached to the anterior skull base, and a subtotal resection was performed. Histopathologically, the mass was composed mainly of irregular islands of chondroid tissues and mesenchymal elements such as spindle cells in a myxoid stroma (Figure 3). At present, a follow-up CT at 3 years revealed no recurrence.

CT of sinonasal cavity. (a) An axial non-contrast CT revealed an ovoid soft-tissue mass in the right nasal cavity. (b ) An axial contrast-enhanced CT image showed marked enhancement. (c) A coronal contrast-enhanced CT image revealed a marked enhanced mass which extends into the anterior cranial fossa and erodes the cribriform plate (arrow). The nasal septum was deviated to the left and the right nasal cavity dilated.

MR Imaging of sinonasal cavity. (a) An axial T1-weighted MRI revealed a mildly hypointense mass in the right nasal cavity. (b) An axial T2-weighted MRI showed a well-defined hyperintense mass and strong signal in both maxillary sinuses. (c) A coronal contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI showed striking enhancement of the mass, extending into the anterior fossa with intact dura.

Case 2

A 6-week-old girl, born at full term by transvaginal delivery, presented with a 4-week history of left nasal watery rhinorrhea and obstruction. Physical examination revealed a purple polypoid mass in the left nasal cavity. All other findings of her medical and family history were unremarkable. Non-contrast CT scans revealed a 2.6 × 3.4 × 3.9 cm well-defined, expansile mass with amorphous calcification in the left nasal cavity (Figure 4). The mass caused pressure remodeling of the adjacent bones without evidence of destruction or invasion of the adjacent structures. MRI demonstrated that the signal intensity of the mass was heterogeneous on T1- and T2-weighted images. The T2-weighted images further showed multiple round areas of high signal intensity within the lesion. The majority of the mass showed a strongly heterogeneous enhancement and the multiple round areas of high signal intensity on T2-weighted images were demonstrated as non-enhancing cystic components after administration of contrast medium (Figure 5). Total resection of the mass was performed in this patient. Histopathologically, the mass was composed of multiple irregular cartilage islands in mesenchymal elements such as spindle cells in a myxoid stroma. The patient is currently doing well postoperatively, without evidence of residue or recurrence according to a 10-month follow-up CT scan.

MR Imaging of sinonasal cavity. (a) An axial T2-weighted MRI showed a well-defined, heterogeneous hyperintense mass containing multiple small round areas of higher signal intensity (arrow). (b) Axial contrast-enhanced fat-suppressed T1-weighted image demonstrated striking heterogeneous enhancement of the mass with multiple non-enhanced cystic components within the lesion (arrow).

Discussion

The most common sinonasal tumors are epithelial in nature. However, nasal masses, including those of epithelial and mesenchymal origin, are infrequently encountered in young infants and children. Nasal hamartomatous lesions may be predominantly composed of mesenchymal and epithelial elements. Several different types of hamartomatous lesions, including angiomatous, lipomatous, chondroid, neurogenic, and epithelial hamartomas, depending on preponderant tissue, have been documented in the literature [4–7]. Mesenchymal hamartomas are more common than epithelial lesions, but a hamartoma of purely epithelial elements has not been described in children [8].

The initial diagnosis of NCMH can be difficult or mistaken radiographically. A correct diagnosis is made primarily from histopathologic examination. However, CT or MRI are diagnostic imaging techniques of choice because they can reveal the tumor’s site of origin, extension, and relationships to adjacent structures, and can also help determine the texture of the mass and aid in planning resection surgery. Most reported cases involved a heterogeneous soft-tissue mass, which were predominantly solid and cystic with or without calcification on a CT scan [1, 3, 7, 10, 11]. The solid component of the tumor is usually strongly enhanced. The lesion is inhomogeneous with low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and with high signal intensity on T2-weighted images with strongly inhomogeneous contrast enhancement. Calcification may be an important diagnostic clue which may help differentiate it from other nasal masses. In a review of CT imaging characteristics of 15 reported cases with NCMH [11], 67% revealed bony remodeling, thinning, or erosion, 53% demonstrated ethmoid sinus or intracranial extension through the cribriform plate, 50% demonstrated internal calcifications, 40% showed cystic components, and 67% demonstrated moderate to strong enhancement. In our two cases, CT of the lesion showed a well-demarcated homogeneous or heterogeneous soft-tissue mass with strong enhancement. In addition, it had low signal intensity on T1-weighted MRI and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images, with marked heterogeneous enhancement; 50% demonstrated calcification or apparent cystic portions within the lesions, which is similar to other reported cases in the literature [11].

The differential diagnosis of NCMH mainly includes nasoethmoidal encephalocele, nasal glioma, rhabdomyosarcoma, lymphoma, and chondrosarcoma. Nasoethmoidal encephaloceles often show mixed density or central soft tissue and peripheral water without marked enhancement, as well as a defect in bone, but no destruction of the anterior cranial fossa [13]. Nasal gliomas embryologically connect to the brain and are partially or completely sealed off with the same signal characteristics as the brain on MRI [12, 13]. Nasal lymphomas are usually homogeneous soft-tissue masses with uniform mild enhancement that distinguish them from NCMH. It can be very difficult to differentiate NCMH from rhabdomyosarcoma and chondrosarcoma radiographically, but the latter two tend to have a much more destructive, ill-defined, and rapid-growing nature [14].

Conclusions

We present two cases of NCMH to alert others that an intranasal mass should be added to the list of differential diagnoses. NCMH is a rare, benign tumor-like lesion with good biologic behavior. No recurrence after complete resection or malignant transformation of NCMH has been reported. A correct diagnosis is imperative to avoid unnecessary adjuvant therapy.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editor-in-chief of this journal.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- HU:

-

Hounsfield Units

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NCMH:

-

Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma.

References

McDermott MB, Ponder TB, Dehner LP: Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma: an upper respiratory tract analogue of the chest wall mesenchymal hamartoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998, 22: 425-433. 10.1097/00000478-199804000-00006.

Shet T, Borges A, Nair C, Desai S, Mistry R: Two unusual lesions in the nasal cavity of infants—a nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma and an aneurysmal bone cyst like lesion: more closely related than we think?. Int Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2004, 68: 359-364. 10.1016/j.ijporl.2003.10.014.

Kim B, Park SH, Min SH, Rhee JS, Wang KC: Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma of infancy clinically mimicking meningoencephalocele. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2004, 40: 136-140. 10.1159/000079857.

Adair CF, Thompson LDR, Wenig BM, Heffner DK: Chondroosseous and respiratory epithelial hamartomas of sinonasal tract and nasopharynx [abstract]. Mod Pathol. 1996, 9: 100-

Kim DW, Low W, Billman G, Wickkersham J, Kearns D: Chondroid hamartoma presenting as a neonatal nasal mass. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1999, 47: 253-259. 10.1016/S0165-5876(98)00121-9.

Ozolek JA, Carrau R, Barnes EL, Hunt JL: Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma in old children and adults: series and immunohistochemical analysis. Arch Patholo Lab Med. 2005, 129: 1444-1450.

Norman ES, Bergman S, Trupiano JK: Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma: report of a case and review of the literature. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2004, 7: 517-520. 10.1007/s10024-004-1003-2.

Hsueh C, Hsueh S, Gonzalez-Crussi F, Lee T, Su T: Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma in children: report of 2 cases with review of the literatures. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001, 125: 400-403.

Kato K, Ijiri R, Tanaka Y, Hara M, Sekido K: Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma of infancy: the first Japanese case report. Pathol Int. 1999, 49: 731-736. 10.1046/j.1440-1827.1999.00933.x.

Alrawi M, McDermott M, Orr D, Russell J: Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma presenting in an adolescent. Int Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2003, 67: 669-677. 10.1016/S0165-5876(03)00067-3.

Johnson C, Nagaraj U, Esguerra J, Wasdhl D, Wurzbach D: Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma: radiographic and histopathologic analysis of a rare pediatric tumor. Pediatr Radiol. 2007, 37: 101-104. 10.1007/s00247-006-0352-6.

Kim JE, Kim HJ, Kim JH, Ko YH, Chung SK: Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma: CT and MR imaging findings. Korean J Radiol. 2009, 10: 416-419. 10.3348/kjr.2009.10.4.416.

Barcovich AJ, Vandermarck P, Edwards MSB, Cogen PH: Congenital nasal masses: CT and MR imaging features in 16 cases. Am J Neuroradiol. 1991, 12: 105-116.

Moron FA, Morriss MC, Jones JJ, Hunter JV: Lumps and bumps on the head in children: use of CT and MR imaging in solving the clinical diagnostic dilemma. Radiographics. 2004, 24: 1655-1674. 10.1148/rg.246045034.

Acknowledgements

Written informed consent was obtained from the two patients for publication of these case reports.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

TT Wang contributed as diagnostic radiologists. WH Li planned, designed and analyzed the study, collected data and wrote the manuscript. QQ Li, YF Cui, CT Chu, and G Ren collected data. XR Wu contributed as a pathologist and helped in writing the manuscript. ML Xiang contributed as otolaryngology–head and neck surgeon and performed the operation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, T., Li, W., Wu, X. et al. Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma in young children: CT and MRI findings and review of the literature. World J Surg Onc 12, 257 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7819-12-257

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7819-12-257