Abstract

Collision tumors of the sellar region are relatively uncommon and consist mainly of more than one type of pituitary adenoma or a cyst or cystic tumor. The association of a pituitary adenoma and a craniopharyngioma is particularly rare. This study describes a rare occurrence in which a pituitary adenoma and a craniopharyngioma coexisted in the sellar region. The case involves a 47-year-old woman who underwent transsphenoidal surgery with subtotal tumor resection and reoperation using an interhemispheric transcallosal approach for total microsurgical resection of the tumor because the visual acuity in her left eye had re-deteriorated. Histopathological and immunohistochemical examinations of the excised tissue revealed a pituitary adenoma in the first operation and a craniopharyngioma in the second operation. Retrospective analysis found the coexistence of a pituitary adenoma and a craniopharyngioma, known as a collision tumor. Instead of the transsphenoidal approach, a craniotomy should be performed, to explore the suprasellar region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pituitary adenomas and craniopharyngiomas are two types of common tumors in the sellar or suprasellar areas. Pituitary tumors represent 10% to 15% of all intracranial tumors, with an annual incidence of 0.2 to 2.8 cases per 100,000 persons [1]. Craniopharyngiomas represent 1% to 4% of all primary intracranial neoplasms and occur at a rate of 1.3 per million person years [2]. The coexistence of these two neoplasms in the sellar or suprasellar areas is rare, and both lesions can attain a large size and cause similar signs and symptoms. This similarity makes the diagnosis and treatment of these coexisting tumors difficult. In this report, we present a case in which a pituitary adenoma and a craniopharyngioma were found to coexist. The case involves a 47-year-old woman who underwent transsphenoidal surgery with subtotal pituitary adenoma resection and reoperation using an interhemispheric transcallosal approach for total microsurgical resection of the craniopharyngioma.

Case presentation

History and examination

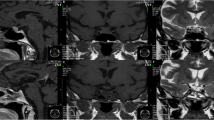

A 47-year-old right-handed woman presented with intermittent blurred vision of the left eye and headaches, which she had had for 5 months. She had also suffered from sore roughening or splitting of the palms and arches for 6 months. The patient had been pregnant twice with normal deliveries, and she had not reached menopause at admission. Neurological examination revealed no obvious clinical signs. The patient complained of decreased vision in her left eye. An examination of her visual acuity revealed that her left eye had almost no distant vision. Visual field testing showed that her left eye’s mean sensitivity and mean defect were significantly decreased compared with the normal value. Ophthalmic fundus examination of both eyes did not show any obvious abnormality. The vision of the patient’s right eye was 5/4, and the mean sensitivity and mean defect were decreased but higher than in the left eye. An endocrine evaluation revealed increased levels of prolactin (111.9 ng/ml, reference value: 2 ng/ml to 25 ng/ml) and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) (116.7 pg/ml, reference value: 11.6 pg/ml to 70.8 pg/ml). Levels of other hormones, including luteinizing hormone, growth hormone, and follicle-stimulating hormone were normal. Other physical examinations revealed that the patient had no other clinical symptoms, neurologic deficits, or other hormonal dysfunction. Biochemical evaluations, including analysis of blood chemistry, electrolyte levels, and urine did not show any obvious abnormality. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the patient’s brain revealed an abnormal signal in the sellar and suprasellar areas, owing to the presence of a partial contrasting mass with clear edges (Figure 1). The patient was diagnosed with pituitary adenoma.

Preoperative images of computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. (A) Sagittal CT showing isodensity or slightly higher density in the sellar and suprasellar areas (arrow indicates the cystic mass in the suprasellar areas). (B,C) Transverse MRI showing a short T1-weighted signal in the sellar area and prepontine cistern and a short T2-weighted signal (arrows indicate the mass). (D-F) Contrast MRI showing an enhanced mass in the sellar and suprasellar areas with a cystic mass in the prepontine cistern (D,F; arrows indicate the mass. E; arrow indicates the cystic mass in the prepontine cistern).

Operation and post-operative course

Transsphenoidal surgery was performed. The tumor was pinkish-gray and soft, and some parts had a rich blood supply with hemorrhage. Subtotal tumor resection was achieved. Staining with H & E revealed a pituitary adenoma consisting of a diffused expansion of cells with pseudo-acinar and pseudo-papillary features (Figure 2A). Immunohistochemical stains for growth hormone, prolactin, follicle-stimulating hormone, thyroid-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, and ACTH were negative, revealing a nonfunctional pituitary adenoma (Figure 2B-G). After surgery, the patient had transient diabetes insipidus and hyponatremia, but she demonstrated fast recovery and her vision improved.

Second admission and examination

After 4 months, a follow-up MRI showed an enlarged region of isodensity in the suprasellar and prepontine areas (Figure 3, arrow point). An enlarged mass corresponding to the ‘cystic lesion’ area was observed in the preoperative image (Figure 1A and E, arrow point). After retrospective analysis, the cystic expansion was believed to be a result of the decompression caused by pituitary tumor resection. The patient was followed up because she had no other clinical symptoms or signs. At 9 months after the initial operation, the patient complained that the visual acuity of her left eye had deteriorated again. Two months later, she came back to our hospital for further examination. Ophthalmologic examination revealed that the status of her left eye was very poor, with almost no visual acuity, and she was not able to maintain visual field detection. Her right eye visual acuity had decreased slightly compared with the previous evaluation (from 5/4 to 5/5), and its visual field was also decreased. Ophthalmic fundus examination of both eyes did not show any obvious abnormality. Endocrinological testing showed normal levels of prolactin, ACTH, follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, growth hormone, and free T4 with only slightly decreased levels of free T3 (1.72 nmol/l, reference value: 2.2 nmol/l to 4.2 nmol/l) and thyroid-stimulating hormone (0.3 μIU/ml, reference value: 0.47 μIU/ml to 4.95 μIU/ml). Sagittal CT and MRI showed an abnormal mixed signal in the suprasellar area and the prepontine cistern, corresponding to a partial contrasting mass with clear edges (Figure 4, arrow point). The patient was diagnosed with recurrent pituitary adenoma.

Second operation and post-operative course

The patient underwent a right frontal craniotomy using an interhemispheric transcallosal approach for total microsurgical resection of the tumor. The tumor was situated in the suprasellar area and premesencephalon. It was cystic, soft, and yellow-white. Histopathological studies revealed an adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma characterized by squamous epithelium arranged in a trabecular pattern as well as nodules of wet keratin (Figure 5). The post-operative course of the patient was uneventful, with the exception of transient diabetes insipidus and hyponatremia. Endocrinologic testing showed only that levels of free T3 and thyroid-stimulating hormone were slightly lower than normal. The patient’s visual acuity improved again. After 3 months, a follow-up MRI confirmed complete resection of the tumor (Figure 6).

Discussion

Collision tumors represent two morphologically different tumors that are attached to each other [3]. Although pituitary adenomas and craniopharyngiomas are two of the most common tumors in the sellar or suprasellar areas, the coexistence of a pituitary adenoma and a craniopharyngioma is rare. Only a few cases have been reported; their clinicopathological features are summarized in Table 1[4–16]. Table 1 summarizes 14 cases (including two cases reported in China in Chinese) of tumors found in ten men and four women with ages ranging from 12 to 75. The prolactin type of pituitary adenoma was the most frequent (eight cases), in addition, there were two cases of ACTH (including the present case) and one case of thyroid-stimulating hormone; the remaining cases were the nonfunctional or silent type. The most well-documented cases of craniopharyngioma have been of the adamantinomatous type. The most common clinical features included deteriorating vision and symptoms caused by the abnormal secretion of hormones. These features are similar to those of pituitary adenoma or craniopharyngioma alone. No obvious features were observed in CT and MRI images to identify this coexistence.

Given the similarities of the clinical and imaging features to those of pituitary adenomas, a preoperative diagnosis of a dual pathological condition of the sella is highly difficult. A definitive diagnosis of a collision sellar lesion is usually based on histological studies. In this case, preoperative MRI showed two abnormal masses attached to each other with different signal intensities (Figure 1A,E). The calcification on the CT imaging in Figure 1A was ignored at first, and the preoperative imaging findings were considered to indicate a pituitary adenoma with cystic changes. The cystic mass was expected to shrink naturally after transsphenoidal surgery of the pituitary adenoma, but instead it increased in size after the surgery. The cystic mass was still not given sufficient attention, and it was believed that the cystic dilatation had been caused by the decreased pressure after removal of the pituitary adenoma. It was only when the patient’s visual acuity in her left eye deteriorated and the imaging was repeated that the tumor recurrence was identified. A review of the histological diagnoses of this case, namely, a pituitary adenoma in the first operation and a craniopharyngioma in the second operation, revealed that ‘a pituitary adenoma with cystic changes’ was in fact coexisting pituitary adenoma and craniopharyngioma and that ‘the cystic changes’ were features of a craniopharyngioma lesion. Although the transsphenoidal approach is the first choice for the resection of most pituitary adenomas, craniotomy should be performed to explore the suprasellar region for coexisting tumors. If the cystic part can be identified as a craniopharyngioma during the first procedure, a craniotomy should be performed to explore the suprasellar region, rather than the transsphenoidal approach, and a second surgery might thereby be avoided. After the second operation, the tumor was completely removed surgically using the interhemispheric transcallosal approach. During a follow-up period of 3 months, the patient was alive and well, with no evidence of disease progression. MRI showed total tumor resection with post-surgical changes (Figure 6).

The tumorigenesis of the coexisting pituitary adenoma and craniopharyngioma is unclear. Yoshida et al. [11] reported a case of pituitary adenoma intermingled with adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma-like components in a young man, but an intermediate morphological phenotype was not found between the two types of tumor. Gokden and Mrak [15] reported a nonfunctioning pituitary adenoma with an intermingled craniopharyngioma component that did not form two distinct lesions. In their study, a histological delineation was also absent, although multiple foci corresponding to the transition from an ordinary pituitary adenoma to an adenoma with squamoid and then adamantinomatous areas were described by pathological examination. Moshkin et al. [14] reported a collision tumor, and histological analysis revealed it to be an adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma. However, electron microscopy showed adenoma cells with the ultrastructural features of a silent pituitary adenoma subtype 3. Aside from these three cases, in which the pituitary adenoma and craniopharyngioma components were admixed, additional cases in which the two components are distinct have been reported. Our study describes another case with the association of a pituitary adenoma and a craniopharyngioma, in which the two components are separated. In general, a neoplasm with dual internal phenotypes is can be explained using metaplastic mechanisms, but the histogenesis of the aforementioned collision tumors is still uncertain. Among the cases of collision tumors listed in Table 1, eight cases had hyperprolactinemia. With respect to the tumorigenesis of these types of concurrent tumor, Cusimano et al. [10] postulated that the loss of the inhibitory hypothalamic dopaminergic input due to pituitary stalk compression by craniopharyngioma is intimately associated with the pathogenesis of lactotroph hyperplasia and prolactinoma. In updated cases, reports on the pathological types of pituitary adenomas other than prolactinoma are available. However, the malfunction of hypothalamic dopaminergic input caused by craniopharyngioma does not explain the formation of nonfunctional or ACTH adenoma. A determination of the mechanisms responsible for the collision coexistence of the two tumor types requires further study.

Conclusions

The concurrence of pituitary adenoma and craniopharyngioma is rare and represents a serious problem in clinical and imaging diagnoses. If we had been aware of the possibility of the concurrence (it is completely possible to make a correct diagnosis based on pathology and imaging characteristics), we would have avoided the second operation resulting from the misdiagnosis. For a patient with a pituitary adenoma and craniopharyngioma collision tumor, a craniotomy should be performed to explore the suprasellar region, rather than a transsphenoidal approach.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editor-in-chief of this journal.

Abbreviations

- ACTH:

-

Adrenocorticotropic hormone

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- H & E:

-

Hematoxylin and eosin

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging.

References

Asa SL, Ezzat S: The cytogenesis and pathogenesis of pituitary adenomas. Endocr Rev. 1998, 19: 798-827. 10.1210/er.19.6.798.

Bunin GR, Surawicz TS, Witman PA, Preston-Martin S, Davis F, Bruner JM: The descriptive epidemiology of craniopharyngioma. J Neurosurg. 1998, 89: 547-551. 10.3171/jns.1998.89.4.0547.

Koutourousiou M, Kontogeorgos G, Wesseling P, Grotenhuis AJ, Seretis A: Collision sellar lesions: experience with eight cases and review of the literature. Pituitary. 2010, 13: 8-17. 10.1007/s11102-009-0190-2.

Prabhakar V, Rao BD, Subramanyam MV: Pituitary adenoma associated with craniopharyngioma. J Pathol. 1971, 103: 185-187. 10.1002/path.1711030307.

Shishkina VL, Kasumova SI, Snigireva RI, Miakota AE: Craniopharyngioma associated with pituitary adenoma and chordoma of Blumenbach’s clivus. Zh Vopr Neirokhir Im N N Burdenko. 1981, 6: 52-54.

Wheatley T, Clark JD, Stewart S: Craniopharyngioma with hyperprolactinaemia due to a prolactinoma. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1986, 49: 1305-1307. 10.1136/jnnp.49.11.1305.

Dong Y, Song YX, Qi W: A case of pituitary adenoma associated with craniopharyngioma. Chin J Neurosurg. 1986, 2: 195-

Asari J, Yamanobe K, Sasaki T, Yamao N, Kodama N: A case of prolactinoma associated with craniopharyngioma. No Shinkei Geka. 1987, 15: 1313-1318.

Jiang ZW, Cheng BL: Pituitary adenoma associated with craniopharyngioma: a case report. Acad J Second Mil Med Univ. 1987, 8: 67-

Cusimano MD, Kovacs K, Bilbao JM, Tucker WS, Singer W: Suprasellar craniopharyngioma associated with hyperprolactinemia, pituitary lactotroph hyperplasia, and microprolactinoma. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1988, 69: 620-623. 10.3171/jns.1988.69.4.0620.

Yoshida A, Sen C, Asa SL, Rosenblum MK: Composite pituitary adenoma and craniopharyngioma?: an unusual sellar neoplasm with divergent differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008, 32: 1736-1741. 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181753abd.

Karavitaki N, Scheithauer BW, Watt J, Ansorge O, Moschopoulos M, Llaguno AV, Wass JA: Collision lesions of the sella: co-existence of craniopharyngioma with gonadotroph adenoma and of Rathke’s cleft cyst with corticotroph adenoma. Pituitary. 2008, 11: 317-323. 10.1007/s11102-007-0070-6.

Sargis RM, Wollmann RL, Pytel P: A 59 year-old man with sellar lesion. Brain Pathol. 2009, 19: 161-162.

Moshkin O, Scheithauer BW, Syro LV, Velasquez A, Horvath E, Kovacs K: Collision tumors of the sella: craniopharyngioma and silent pituitary adenoma subtype 3: case report. Endocr Pathol. 2009, 20: 50-55. 10.1007/s12022-009-9065-3.

Gokden M, Mrak RE: Pituitary adenoma with craniopharyngioma component. Hum Pathol. 2009, 40: 1189-1193. 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.02.007.

Finzi G, Cerati M, Marando A, Zoia C, Ferreli F, Tomei G, Castelnuovo P, Rosa SL, Capella C: Mixed pituitary adenoma/craniopharyngioma: clinical morphological, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study of a case, review of the literature, and pathogenetic and nosological considerations. Pituitary. 2013, 10.1007/s11102-013-0465-5.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Lin Luo and Guilin Li for kindly re-evaluating the pathological specimen and Professor Shaowu Li for helpful comments on radiologic interpretation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

GJ and SH reviewed the literature and drafted the manuscript. FL was clinically responsible for the patient’s care and revised the manuscript. JX and RM were responsible for the pathology and radiological images. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Jin, G., Hao, S., Xie, J. et al. Collision tumors of the sella: coexistence of pituitary adenoma and craniopharyngioma in the sellar region. World J Surg Onc 11, 178 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7819-11-178

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7819-11-178