Abstract

Background

Unambiguous interpretation of ordered rating scale response categories requires distinct meanings of category labels. Also, summation of item responses into total scores assumes equal intervals between categories. While studies have identified problems with rating scale response category functioning there is a paucity of empirical studies regarding how respondents interpret response categories. We investigated the interpretation of commonly used rating scale response categories and attempted to identify distinct and roughly equally spaced response categories for patient-reported rating scales in Parkinson's disease (PD) and age-matched control subjects.

Methods

Twenty-one rating scale response categories representing frequency, intensity and level of agreement were presented in random order to 51 people with PD (36 men; mean age, 66 years) and 36 age-matched controls (14 men; mean age, 66). Respondents indicated their interpretation of each category on 100-mm visual analog scales (VAS) anchored by Never - Always, Not at all - Extremely, and Totally disagree - Completely agree. VAS values were compared between groups, and response categories with mean values and non-overlapping 95% CIs corresponding to equally spaced locations on the VAS line were sought to identify the best options for three-, four-, five-, and six-category scales.

Results

VAS values did not differ between the PD and control samples (P = 0.286) or according to educational level (P = 0.220), age (P = 0.220), self-reported physical functioning (P = 0.501) and mental health (P = 0.238), or (for the PD sample) PD duration (P = 0.213) or presence of dyskinesias (P = 0.212). Attempts to identify roughly equally spaced response categories for three-, four-, five-, and six-category scales were unsuccessful, as the 95% CIs of one or several of the identified response categories failed to include the criterion values for equal distances.

Conclusions

This study offers an evidence base for selecting more interpretable patient-reported rating scale response categories. However, problems associated with raw rating scale data, primarily related to their ordinal structure also became apparent. This argues for the application of methodologies such as Rasch measurement. Rating scale response categories need to be treated with rigour in the construction and analysis of rating scales.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Patient-reported rating scales are gaining increasing importance in determining patient status and effectiveness of therapies. In such scales, responses to a number of items are typically summed to yield a total score intended to locate the respondent on a continuum from less to more on the variable of interest. Following the tradition of Likert [1], this is achieved by assigning integral numerals (e.g., 0 - 1 - 2 - 3) to descriptive response categories (e.g., none - mild - moderate - severe) as a means of partitioning the underlying latent quantitative continuum into successively increasing (or decreasing) amounts of the variable.

Although the summed rating scale approach may appear simple and straight forward, its appropriateness and legitimacy rests on some fundamental assumptions that often appear overlooked. First, for respondents to be able to communicate their positions accurately (and for investigators and clinicians to accurately interpret those responses), the descriptive response category labels need to have distinct and unambiguous meanings that reflect differences in amount [2]. Second, for arithmetic operations, such as summation of integral numerals assigned to response categories to be performed and interpreted legitimately, the magnitudes that successive categories represent need to be equally spaced [3, 4]. Recently, these criteria have been emphasized by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for patient-reported rating scales to be considered appropriate as clinical trial endpoints [5].

Although attention has been paid to these and related issues in the behavioral and social sciences [2, 6–8], less work appears to have been conducted in the clinical health sciences [9–11]. Furthermore, a considerable number of participants in available studies in the health arena have not suffered from any specific medical conditions [9–11]. Particularly, there seems to be a lack of this type of study in the clinical neurosciences. However, studies have shown that rating scale response categories often do not function as expected and required among people with neurological disorders such as Parkinson's disease (PD), multiple sclerosis and stroke [12–18]. These studies illustrate that although a larger number of response categories generally tend to increase variance and, hence, correlations and reliability coefficients [6], this is not always the case and might be at the expense of validity [6, 14, 16, 17, 19]. Consideration of how neurological respondents interpret rating scale response categories is therefore warranted in order to provide an evidence base for their selection when developing and modifying patient-reported rating scales. Additionally, it is unclear whether rating scale response category interpretations differ between people with long-term illnesses and control subjects, since we have been unable to identify any controlled studies of this kind. This may be particularly relevant in chronic unpredictable neurological disorders, such as PD, that impacts a variety of functions.

The objective of this study was to investigate the interpretation of commonly used rating scale response categories and to identify distinct and roughly equally spaced response categories for patient-reported rating scales in PD and age-matched control subjects.

Methods

Two samples were used: 51 consecutive Swedish speaking people with neurologist diagnosed PD [20] without clinically significant mental impairments (e.g. dementia, confusion) were recruited from a Swedish university hospital, and 36 age-matched controls without neurological disorders were recruited through snowball sampling. In addition to age, it was desired that controls should have approximately the same educational background as the PD sample.

Participants were interviewed regarding demographic characteristics and self-completed the physical functioning and mental health scales of the SF-36 [21, 22]. People with PD were also assessed regarding Hoehn & Yahr stages of PD severity [23]. Participants were then presented with 21 rating scale response options representing ratings of frequency, intensity and level of agreement (see Table 1). Respondents indicated their interpretation of each of the 21 response categories on 100-mm visual analog scales (VAS) anchored by Never - Always (frequency), Not at all - Extremely (intensity), and Totally disagree - Completely agree (agreement) [9, 10]. Categories and anchors were taken from patient-reported rating scales used in PD [22, 24–29]. Response categories were presented one at a time, on separate sheets and in random order; each sheet consisted of one response category and a corresponding 100-mm anchored VAS line. Before commencing this part of the data collection, the investigators ascertained that participants understood the task by explaining the procedure and its objective. In doing so, the task was illustrated by an example relating the word "warm" to a VAS line anchored by "ice cold" and "boiling hot". During data collection, any comments regarding the response categories and their interpretation were recorded. If a respondent was unable to assess the magnitude of a response category, this was recorded as a missing value.

The study was reviewed by the institutional ethics advisory committee and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent.

Analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 14 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago IL). P-values were adjusted for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure [30], and considered statistically significant when < 0.05. The distribution of data was assessed regarding univariate and multivariate normality (Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Mardia's tests) and described and analyzed accordingly.

Group comparisons of rating scale response category interpretations

Nonparametric multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) [31] was used to compare VAS values from PD and control respondents. If no significant differences between groups were identified, the pooled data was used to explore (using nonparametric MANOVA) whether VAS values differed according to educational level (university/professional degree vs others), age, physical functioning and mental health (with the latter three dichotomized by their median values). For the PD group, differences in VAS values according to PD duration (dichotomized by the median) and whether patients experienced dyskinesias or not were also explored.

Identification of distinct rating scale response categories

To determine the best response options for the three types of ratings, the mean, standard deviations (SD) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the VAS values were examined [9, 10]. The criterion was that mean VAS values (or their associated 95% CIs) should be distributed equally across the 0-100 mm continuum, assuming the values of 0 and 100 for the predefined extreme anchor categories. This was done for three-, four-, five- and six-category response scales. For example, for a five-category response scale, the three response categories with mean VAS values closest to 25, 50 and 75 mm were identified and each 95% CI was examined to determine if it covered the criterion value. For three-, four- and six-category response scales the corresponding reference locations were 50 mm (three categories), 33 and 67 mm (four categories) and 20, 40, 60 and 80 mm (six categories). In addition to roughly equal distances between mean locations, the 95% CIs for the VAS values of the selected response categories should not overlap. If two or more response categories met these criteria, the one with the smallest dispersion (SD) was selected. Finally, participants' comments were also taken into account when determining response category suitability.

Results

Sample characteristics are reported in Table 2. There were no differences between people with PD and controls regarding age, educational levels or mental health scores, but there were more men in the PD sample, and controls had better physical functioning scores than people with PD (Table 2). Data collection also took significantly longer for people with PD (mean [SD], 17.4 [7.2] minutes) than for controls (mean [SD], 12.7 [4.3] minutes) to complete (P = 0.001; unpaired t-test). In the PD group, 94% were treated with levodopa, 82% were on dopamine agonists, COMT- and MAO-inhibitors were used among 43% each, and 25% had undergone a neurosurgical intervention for their PD.

Group comparisons of rating scale response category interpretations

MANOVA of overall differences among VAS values between PD and control groups was not significant (P = 0.286). Similarly, MANOVAs of VAS values for the pooled sample did not display any significant differences between educational levels (P = 0.220), age groups (P = 0.220), or between people with lower and higher physical functioning (P = 0.501) and mental health (P = 0.238) scores. In the PD sample, there were no differences between people with shorter and longer disease durations (P = 0.213) or between those with or without dyskinesias (P = 0.212).

Identification of distinct rating scale response categories

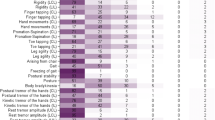

Results from the VAS evaluations of the 21 rating scale response categories from the pooled sample are presented in Table 1 and Figure 1, with categories organized in ascending order (from lower to higher mean VAS values) within each of the three response category types. Additional file 1 presents the corresponding data separately for people with PD and controls.

Response category mean VAS values and 95% CIs. Mean values (black dots) with associated 95% confidence intervals (error bars) for 100-mm visual analog scale (VAS) ratings (y-axis) of the perceived meaning of response category wordings (x-axis) in relation to (A) Never (0 mm) - Always (100 mm), (B) Not at all (0 mm) - Extremely (100 mm), and (C) Totally disagree (0 mm) - Completely agree (100 mm) among people with Parkinson's disease (n = 51) and an age-matched control group (n = 36). See Methods for details.

One third (n = 12) of the control group and 43% (n = 22) of the PD group expressed difficulties interpreting the response category Don't know. Difficulties were also expressed by one or two respondents each for the categories Sometimes, Somewhat, Moderately, and Do not agree or disagree.

Based on these observations the best three-, four-, five and six-category response scales according to the pre-defined criteria are provided in Figure 2. It can be seen that the equal distances criterion was not fully met in either of the identified three-, four-, five or six-category response scales for any of the three types of ratings. The proportion of categories whose 95% CI covered the criterion VAS values was highest for the six-category agreement scale (75%), followed by the five category scales for all three types of ratings (67%).

Selected response categories. Selected response categories for three-, four-, five-, and six-category response scales as determined from observed visual analog scales (VAS) values. See Methods for details.

* 95% CI of category VAS value does not cover criterion value. Arrows indicate direction of discrepancy (←, below criterion value; →, above criterion value); see Table 1 for raw data.

Discussion

This appears to be the first controlled study on the interpretation of patient-reported rating scale response categories in the clinical neurosciences. As such, it provides a first evidence base and initial guidance for selection of rating scale response categories when developing new or modifying available patient-reported rating scales for PD. This is highly relevant as clarity, distinctiveness and equality of response category intervals represent fundamental assumptions underpinning traditional rating scale construction [1, 32] that are recognized by, e.g. the FDA when judging the appropriateness of rating scales as clinical trial endpoints [5]. Although focusing on PD, the lack of systematic differences between people with PD and age-matched controls, as well as between other health-related respondent characteristics, suggests that our findings are relevant beyond this context.

The identified best categories for three-, four-, five and six-category response scales were not optimal, as they failed to fulfill the assumption of equal inter-category distances also when considering their 95% CIs. For example, the distances between Some of the time and A good bit of the time are clearly different from those between A good bit of the time and Most of the time. Extrapolating data from this study to response categories in commonly used scales reveals similar problems. For example, the three non-extreme response options in the original PDQ-39 (Occasionally - Sometimes - Often) [27] correspond to mean VAS locations of 30.8, 45.9 and 74.7, respectively. That is, the estimated distance between the latter two categories is about twice as large as that between the former two. Similar or more extreme situations are evident with scales such as the PFS-16 [24], FACIT-F [29], SF-36 [22], PDQL [25], and PDQUALIF [28].

Conceivably, this has at least two consequences. First, it may contribute to respondent difficulties in using the response options. Second, it is unknown what a certain difference in raw rating scale scores represents and by how much more someone has changed compared to people with smaller change scores. This illustrates the ordinal nature of raw rating scale data and argues against the legitimacy of analyzing and interpreting summed integral numerals from item responses as linear measures [3, 33, 34]. This latter aspect represents a fact perhaps partly overlooked when developing rating scales; that is, the profound step that is taken when transforming words (qualitative descriptors) into numbers (quantities) that typically are treated as linear measures.

There are a number of aspects that need to be taken into consideration when interpreting the results presented here. First, the appropriateness of using VAS to evaluate participants' interpretation of response categories may be questioned since evidence speaks against the linearity of VAS data [35]. However, there is also evidence supporting the linearity of VAS ratings [36, 37], and the approach has been found useful in previous studies of rating scale category interpretations [9–11]. Second, our observations refer to the Swedish versions of the studied response categories, and the equivalence between various language versions is dependent on cultural and semantic aspects, as well as the quality of the translation. It has for example been shown that interpretations of the same response category can differ between languages as well as between cultures within the same language [11]. However, the VAS values found here are in general agreement with those reported in previous studies using the same methodology and response categories [9, 10]. This suggests that our observations are not necessarily limited to a Swedish context. Third, we limited the types of response categories to frequency, intensity and agreement, and there are also response categories of these types that were not covered here. Furthermore, the anchor categories were assumed to have fixed values at 0 and 100 mm, whereas their interpretations actually may differ between people. For example, studies investigating the perceived absolute frequency or probability of occurrence associated with frequency descriptors have found variations in the interpretation of Always as well as Never [38, 39].

The samples studied here were not randomly selected, which may limit the generalizability of results. Furthermore, the sample sizes were somewhat limited, which influences the precision of observations and, therefore, renders the reported 95% CIs wider than otherwise would have been the case. However, given that data failed to support the assumption of equal inter-category distances even with consideration of the observed CIs, increasing the number of observations would presumably have yielded even stronger evidence against legitimate raw score summation of the response categories studied here. Similarly, the lack of differences between people with PD and control subjects, as well as between other subgroups also needs to be interpreted in view of the sample size. That is, with increasing numbers of observations, statistically significant differences are increasingly likely to be detected. However, statistical significance says nothing about the practical significance of differences, which is not known for the current type of data.

The variability in interpretations of response categories was wide between individuals (as illustrated by the ranges of VAS values). This does not appear to be limited to patient-reported data, as studies regarding physicians' interpretation of various probability related expressions (including some of the response categories studied here) have shown similar variability [38]. This variability further complicates score interpretation at the individual patient level. An important aspect in this respect is the extent to which interpretations are stable within individuals over time. This needs to be assessed in further studies designed for this purpose. Such studies would also allow for direct evaluation of the error variation in VAS ratings, which is an important aspect for the interpretability of data that was not considered in this study.

Our observations concern the interpretation of response categories without reference to a particular context. This is different from the use of response categories in rating scales where items articulate the context within which responses are requested. Studies have shown that the meaning of descriptors of, e.g. frequency differ according to context as well as respondents' experiences within the context [32, 40]. While this hampers the possibilities to make valid comparisons of raw rating scale data between people and between scales tapping different variables, the magnitude of these effects for various health outcome variables is uncertain and will need to be addressed in future studies.

A large proportion of respondents expressed difficulties with the response category Don't know. This observation is in accordance with previous studies of neutral middle categories (e.g., Undecided, ?, and Not sure) in Likert type response scales [19, 41, 42]. These studies have shown that there may be a variety of reasons why respondents select this type of response category and that in practice, it does not operate as a middle category. It has therefore been recommended that it should not be presented as an integral part of a continuum of levels of agreement but, if used at all, be presented separately from categories expressing agreement levels [41]. The observations reported here provide further qualitative evidence in support for this notion.

The ordinal nature of rating scale response categories challenges the legitimacy of summing individual item scores into total scores, as well as their interpretability [3, 4, 34]. However, there are means to empirically determine how the response categories used with a particular set of items function when administered to a particular group of people, and to overcome the assumption of equal intervals in the construction of total scores. Specifically, the polytomous Rasch measurement model for ordered response categories does not assume equal intervals between response categories, tests whether thresholds between adjacent categories are ordered in the expected manner, and provides a means of exploring the effect of collapsing adjacent categories [19, 41, 43, 44]. Additionally, the Rasch model defines, mathematically, the requirements that data need to meet in order to produce measurements, and when these requirements are met scores can be expressed as invariant measures instead of ordinal numbers [33, 45–47]. This study argues for a wider application of this methodology, including appropriate appreciation of response category functioning, whenever rating scale data are used for measurement. For purposes of assessment (in contrast to measurement [33, 46, 48]) an alternative to summed total scores that takes the ordinal nature of rating scale response categories into consideration would, e.g., be the approaches proposed by Svensson [49].

Conclusions

Although in need of replication and extension, this study offers an evidence base for selecting more interpretable patient-reported rating scale response categories. As such, it provides guidance when developing new or modifying existing rating scales. However, it must be stressed that the selection of response categories also should be guided by additional considerations, so that they express levels of the construct articulated by the items in a meaningful way that is congruent with the intention of the scale. In this perspective, response categories alternative to those primarily identified here may be appropriate, particularly since the difference between identified and alternative categories in some cases were marginal. Our observations also illustrate problems associated with raw rating scale data that clinicians and investigators need to be aware of and that argue for the application of newer rating scale methodologies such as Rasch measurement. Response categories need to be treated with rigour in the construction and application of rating scales.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COMT:

-

Catechol-O-methyl transferase

- FACIT-F:

-

Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy - Fatigue

- FDA:

-

Food and Drug Administration

- MANOVA:

-

Multivariate analysis of variance

- MAO:

-

Monoamine oxidase

- mm:

-

Millimeter

- PD:

-

Parkinson's disease

- PDQ-39:

-

39-item Parkinson's disease questionnaire

- PDQUALIF:

-

Parkinson's disease quality of life scale

- PFS-16:

-

16-item Parkinson fatigue scale

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SF-36:

-

Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short Form health survey

- VAS:

-

Visual analog scale

References

Likert R: A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology 1932, 140: 1–55.

Krosnick JA: Survey research. Annu Rev Psychol 1999, 50: 537–567. 10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.537

Merbitz C, Morris J, Grip JC: Ordinal scales and foundations of misinference. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1989, 70: 308–312.

Stevens SS: On the Theory of Scales of Measurement. Science 1946, 103: 677–680. 10.1126/science.103.2684.677

Food and Drug Administration: Patient-Reported Outcome measures: Use in Medicinal Product Development to Support Labelling Claims. Washington D.C. 2009. [http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf]

Cox EP: The optimal number of response alternatives for a scale: A review. Journal of Marketing Research 1980, 17: 407–422. 10.2307/3150495

Hawthorne G, Mouthaan J, Forbes D, Novaco RW: Response categories and anger measurement: do fewer categories result in poorer measurement?: development of the DAR5. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2006, 41: 164–172. 10.1007/s00127-005-0986-y

Spector PE: Choosing response categories for summated rating scales. J Appl Psychol 1976, 61: 374–375. 10.1037/0021-9010.61.3.374

Keller SD, Ware JE Jr, Gandek B, Aaronson NK, Alonso J, Apolone G, Bjorner JB, Brazier J, Bullinger M, Fukuhara S, et al.: Testing the equivalence of translations of widely used response choice labels: results from the IQOLA Project. International Quality of Life Assessment. J Clin Epidemiol 1998, 51: 933–944. 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00084-5

Skevington SM, Tucker C: Designing response scales for cross-cultural use in health care: data from the development of the UK WHOQOL. Br J Med Psychol 1999,72(1):51–61. 10.1348/000711299159817

Szabo S, the WHOQOL Group: The World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL) Assessment Instrument. In Quality of Life and Pharmacoeconomics in Clinical Trials. Second edition. Edited by: Spilker B. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996:355–362.

Franchignoni F, Ferriero G, Giordano A, Guglielmi V, Picco D: Rasch psychometric validation of the Impact on Participation and Autonomy questionnaire in people with Parkinson's disease. Europa medicophysica 2007, 43: 451–461.

Franchignoni F, Giordano A, Ferriero G: Rasch analysis of the short form 8-item Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-8). Qual Life Res 2008, 17: 541–548. 10.1007/s11136-008-9341-6

Hagell P, McKenna SP: International use of health status questionnaires in Parkinson's disease: translation is not enough. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2003, 10: 89–92. 10.1016/S1353-8020(03)00110-X

Hagell P, Nilsson MH: The 39-item Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39): is it a unidimensional construct? Therapeutic Advances in Neurological Disorders 2009, 2: 205–214. 10.1177/1756285609103726

Hobart J, Cano S: Improving the evaluation of therapeutic interventions in multiple sclerosis: the role of new psychometric methods. Health Technol Assess 2009., 13: iii, ix-x, 1–177

Nilsson AL, Sunnerhagen KS, Grimby G: Scoring alternatives for FIM in neurological disorders applying Rasch analysis. Acta Neurol Scand 2005, 111: 264–273. 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2005.00404.x

Mills R, Young C, Nicholas R, Pallant J, Tennant A: Rasch analysis of the Fatigue Severity Scale in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2009, 15: 81–87. 10.1177/1352458508096215

Andrich D, De Jong JHA, Sheridan B: Diagnostic opportunities with the Rasch model for ordered response categories. In Applications of latent trait and latent class models in the social sciences. Edited by: Rost J, Langeheine R. Münster: Waxmann Verlag; 1997:58–68.

Gibb WR, Lees AJ: The relevance of the Lewy body to the pathogenesis of idiopathic Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1988, 51: 745–752. 10.1136/jnnp.51.6.745

Hagell P, Törnqvist AL, Hobart J: Testing the SF-36 in Parkinson's disease: Implications for reporting rating scale data. J Neurol 2008, 255: 246–254. 10.1007/s00415-008-0708-y

Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD: The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992, 30: 473–483. 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002

Hoehn MM, Yahr MD: Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology 1967, 17: 427–442.

Brown RG, Dittner A, Findley L, Wessely SC: The Parkinson fatigue scale. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2005, 11: 49–55. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2004.07.007

de Boer AG, Wijker W, Speelman JD, de Haes JC: Quality of life in patients with Parkinson's disease: development of a questionnaire. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1996, 61: 70–74. 10.1136/jnnp.61.1.70

Katzenschlager R, Schrag A, Evans A, Manson A, Carroll CB, Ottaviani D, Lees AJ, Hobart J: Quantifying the impact of dyskinesias in PD: the PDYS-26: a patient-based outcome measure. Neurology 2007, 69: 555–563. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000266669.18308.af

Peto V, Jenkinson C, Fitzpatrick R, Greenhall R: The development and validation of a short measure of functioning and well being for individuals with Parkinson's disease. Qual Life Res 1995, 4: 241–248. 10.1007/BF02260863

Welsh M, McDermott MP, Holloway RG, Plumb S, Pfeiffer R, Hubble J: Development and testing of the Parkinson's disease quality of life scale. Mov Disord 2003, 18: 637–645. 10.1002/mds.10424

Yellen SB, Cella DF, Webster K, Blendowski C, Kaplan E: Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) measurement system. J Pain Symptom Manage 1997, 13: 63–74. 10.1016/S0885-3924(96)00274-6

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y: Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B (Methodological) 1995, 57: 289–300.

Zwick R: Nonparametric one-way multivariate analysis of variance: a computational approach based on the Pillai-Bartlett trace. Psychol Bull 1985, 97: 148–152. 10.1037/0033-2909.97.1.148

Streiner DL, Norman GR: Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their development and use. 4th edition. New York: Oxford University Press Inc; 2008.

Wright BD, Linacre JM: Observations are always ordinal; measurements, however, must be interval. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1989, 70: 857–860.

Zhu W: Should total scores from a rating scale be used directly? Res Q Exerc Sport 1996, 67: 363–372.

Svensson E: Comparison of the quality of assessments using continuous and discrete ordinal rating scales. Biometrical Journal 2000, 42: 417–434. Publisher Full Text 10.1002/1521-4036(200008)42:4%3C417::AID-BIMJ417%3C3.0.CO;2-Z

Hofmans J, Theuns P: On the linearity of predefined and self-anchoring Visual Analogue Scales. Br J Math Stat Psychol 2008, 61: 401–413. 10.1348/000711007X206817

Myles PS, Troedel S, Boquest M, Reeves M: The pain visual analog scale: is it linear or nonlinear? Anesth Analg 1999, 89: 1517–1520. 10.1097/00000539-199912000-00038

Bryant GD, Norman GR: Expressions of probability: words and numbers. N Engl J Med 1980, 302: 411.

Hakel MD: How often is often? Am Psychol 1968, 23: 533–534. 10.1037/h0037716

Schaeffer NC: Hardly ever or constantly? Group comparisons using vague quantifiers. Public Opin Q 1991, 55: 395–423. 10.1086/269270

Andrich D: Understanding ordered category response data from the perspective of the Rasch model. Educ Res Eval 1998, 25: 25–35.

Dubois B, Burns JA: An analysis of the meaning of the question mark response category in attitude scales. Educ Psychol Meas 1975, 35: 869–884. 10.1177/001316447503500414

Andrich D: A rating formulation for ordered response categories. Psychometrika 1978, 43: 561–574. 10.1007/BF02293814

Luo G: The relationship between the Rating Scale and Partial Credit Models and the implication of disordered thresholds of the Rasch models for polytomous responses. J Appl Meas 2005, 6: 443–455.

Andrich D: Rasch models for measurement. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, Inc; 1988.

Hobart JC, Cano SJ, Zajicek JP, Thompson AJ: Rating scales as outcome measures for clinical trials in neurology: problems, solutions, and recommendations. Lancet Neurol 2007, 6: 1094–1105. 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70290-9

Perline R, Wright BD, Wainer H: The Rasch model as additive conjoint measurement. Applied Psychological Measurement 1979, 3: 237–255. 10.1177/014662167900300213

Delandshere G, Petrosky AR: Assessment of complex performances: limitations of key measurement assumptions. Educational Researcher 1998, 27: 14–24.

Svensson E: Construction of a single global scale for multi-item assessments of the same variable. Stat Med 2001, 20: 3831–3846. 10.1002/sim.1148

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all participating respondents for their cooperation. The study was conducted within the Neuroscience Caring and Outcomes Research (NeuroCORE) group, Department of Health Sciences, Lund University. The study was supported by the Swedish Research Council, the Skane County Council Research and Development Foundation, the Swedish Parkinson Foundation, the Swedish Parkinson Academy, and the Faculty of Medicine, Lund University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

IK participated in designing the study, data collection, data analyses and interpretation, and drafting of the manuscript. HR participated in designing the study, data collection, data analyses and interpretation. JR participated in data collection, and drafting of the manuscript. PN participated in designing the study, conducted data analyses, participated in data interpretation, and drafting of the manuscript. PH conceptualized and designed the study, participated in data collection, conducted data analyses, participated in data interpretation and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12955_2009_684_MOESM1_ESM.PDF

Additional file 1: Descriptive response category VAS data separately for people with Parkinson's disease and control subjects. (PDF 13 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Knutsson, I., Rydström, H., Reimer, J. et al. Interpretation of response categories in patient-reported rating scales: a controlled study among people with Parkinson's disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes 8, 61 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-8-61

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-8-61