Abstract

Background

Respiratory symptoms are common in the general population, and their presence is related to Health-related quality of life (HRQoL). The objective was to describe the association of respiratory symptoms with HRQoL in subjects with and without asthma or COPD and to investigate the role of atopy, bronchial hyperresponsiveness (BHR), and lung function in HRQoL.

Methods

The European Community Respiratory Health Survey (ECRHS) I and II provided data on HRQoL, lung function, respiratory symptoms, asthma, atopy, and BHR from 6009 subjects. Generic HRQoL was assessed through the physical component summary (PCS) score and the mental component summary (MCS) score of the SF-36.

Factor analyses and linear regressions adjusted for age, gender, smoking, occupation, BMI, comorbidity, and study centre were conducted.

Results

Having breathlessness at rest in ECRHS II was associated with mean score (95% CI) impairment in PCS of -8.05 (-11.18, -4.93). Impairment in MCS score in subjects waking up with chest tightness was -4.02 (-5.51, -2.52). The magnitude of HRQoL impairment associated with respiratory symptoms was similar for subjects with and without asthma/COPD. Adjustments for atopy, BHR, and lung function did not explain the association of respiratory symptoms and HRQoL in subjects without asthma and/or COPD.

Conclusion

Subjects with respiratory symptoms had poorer HRQoL; including subjects without a diagnosis of asthma or COPD. These findings suggest that respiratory symptoms in the absence of a medical diagnosis of asthma or COPD are by no means trivial, and that clarifying the nature and natural history of respiratory symptoms is a relevant challenge.

Several community studies have estimated the prevalence of common respiratory symptoms like cough, dyspnoea, and wheeze in adults [1–3]. Although the prevalence varies to a large degree between studies and geographical areas, respiratory symptoms are quite common. The prevalences of respiratory symptoms in the European Community Respiratory Health Study (ECRHS) varied from one percent to 35% [1]. In fact, two studies have reported that more than half of the adult population suffers from one or more respiratory symptoms [4, 5].

Respiratory symptoms are important markers of the risk of having or developing disease. Respiratory symptoms have been shown to be predictors for lung function decline [6–8], asthma [9, 10], and even all-cause mortality in a general population study [11]. In patients with a known diagnosis of asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), respiratory symptoms are important determinants of reduced health related quality of life (HRQoL) [12–15]. The prevalence of respiratory symptoms exceeds the combined prevalences of asthma and COPD, and both asthma and COPD are frequently undiagnosed diseases [16–18]. Thus, the high prevalence of respipratory symptoms may mirror undiagnosed and untreated disease.

The common occurrence of respiratory symptoms calls for attention to how these symptoms affect health also in subjects with no diagnosis of obstructive airways disease. Impaired HRQoL in the presence of respiratory symptoms have been found in two population-based studies [6, 19], but no study of respiratory sypmtoms and HRQoL have separate analyses for subjects with and without asthma and COPD, and no study provide information about extensive objective measurements of respiratory health.

The ECRHS is a randomly sampled, multi-cultural, population based cohort study. The ECRHS included measurements of atopy, bronchial hyperresponsiveness (BHR), and lung function, and offers a unique opportunity to investigate how respiratory symptoms affect HRQoL among subjects both with and without obstructive lung disease.

In the present paper we aimed to: 1) Describe the relationship between respiratory symptoms and HRQoL in an international adult general population and: 2) To assess whether this relationship varied with presence of asthma and/or COPD, or presence of objective functional markers like atopy and BHR.

Similar content being viewed by others

Methods

Study population

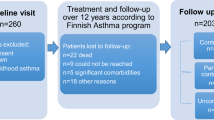

The ECRHS I [20] was undertaken in 1991 through 1993, and comprised representative population samples of adults aged 20-44 years in 48 centres in 22 countries. Altogether 137 619 subjects completed a postal questionnaire on respiratory health, giving a median response rate of 78% (stage I). Randomly selected representative subsamples of subjects from 36 centres participated in interviews and standardised clinical testing (ECRHS I stage II). The ECRHS II [21] was a follow-up study of respondents to ECRHS I stage II, conducted from 1998 through 2002. Of the invited, a total of 11 168 responded (response rate 76%). The respondents completed interviews and standardised clinical testing with blood tests, spirometry, and methacholine challenge. A total of 6009 subjects from 24 centres in 11 countries completed data regarding respiratory symptoms, HRQoL, and lung function in the ECHRS II. The regional ethics committees approved the study, and all participants signed informed consent. The full protocol is available at http://www.echrs.org.

Questionnaire information

Information on respiratory symptoms was obtained in ECRHS II by questions 1-11 listed in appendix 1. Asthma was defined as ever having had asthma, question 12 in appendix 1 (ECRHS II).

Smoking was categorized as never-, ex- and current, where the current smokers were the ones that reported having smoked during the last month in the ECRHS II. The longest held job during the follow up period was used as a marker of socioeconomic status, and classified into 5 groups as 1) managers and professionals; 2) technicians; 3) other non-manual workers; 4) manual workers; and 5) non-classified workers. Data on comorbidities were obtained by the questions listed in appendix 2. Presence of comorbidity was included as a dichotomized variable.

The Short Form-36 (SF-36) questionnaire was used to assess HRQoL in the ECRHS II. The SF-36 is a standardized, widely used and validated general HRQoL questionnaire, which is translated into several languages [22]. It includes 36 questions from which the physical component summary (PCS) and the mental component summary (MCS) were computed as described in the SF-36 User's Manual [23]. The scores were transformed so that the mean score was 50 and the standard deviation was 10 [24]. A higher score indicates better quality of life. In clinical trials, a 5 point change in the MCS and PCS are regarded as clinically relevant, whereas statistical significance can be reached with changes in 1-2 points in the scores.

Objective measurements

Pre-bronchodilator lung function (forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC)) and BHR were measured by standard methods [21]. BHR was defined as a 20% reduction in FEV1 (PD20) after methacholine challenge, with a maximum cumulative methacholine dose of 2 mg [20]. COPD was defined and classified according to the Global initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) [25], i.e FEV1/FVC < 0.70. Because the number of subjects with FEV1 < 50% predicted were small (COPD GOLD stage III and IV), these were grouped together. Specific IgE levels were measured with the Pharmacia CAP System [26], and atopy was defined as assay results > 0.35 kU/L for any of the following allergens: house dust mite (Dermatophagoides Pteronyssinus), timothy grass, cat and mould (Cladosporium Herbarum).

Statistical analyses

The statistical software Stata version 10.1 was used for the statistical analyses [27]. The bivariate relationships between the outcome variables (PCS and MCS) and the respiratory symptoms were described by means and standard deviations and tested with Kruskal Wallis and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Nonparametric test were used due to skewed distributions of the SF-36 scores. The relationship between the SF-36 scores and each of the symptom variables were investigated in robust multiple linear regression models, with adjustments for age, gender, smoking, occupation, body mass index (BMI), comorbidity, and study centre. Stratified analyses were performed with respect to diagnosis (neither asthma nor COPD; and asthma and/or COPD). Respiratory symptoms often occur together, causing problems of co-linearity if included together, in a mutually adjusted model. Therefore, we used exploratory factor analysis, where symptoms with high level of covariance were summarized in a factor. This yields an estimate of the association between having one of the symptoms in the factor, regardless of which, and HRQoL. The factors substituted the observed symptom variables in multiple linear regression analysis with respect to the SF-36 scores, adjusted for atopy, BHR, and FEV1 in addition to age, gender, smoking, occupation, BMI, comorbidity, and study centre.

Results

Demographic details of the study population (ECRHS II) are given in table 1. In bivariate analyses, both PCS and MCS varied significantly with presence of asthma, gender, age, smoking, occupation, BMI, comorbidity, BHR, but not with atopy. PCS varied with COPD stage, while MCS did not.

All the respiratory symptoms were significantly related to both PCS and MCS, the scores being lower in subjects reporting symptoms (table 2). Breathlessness at rest was the symptom related to the lowest score, both for PCS and MCS. The least impairment in the scores was observed in subjects with cough in the night. A similar pattern of score decrement was observed in multivariate analyses, adjusting for age, gender, smoking, comorbidity, occupation, BMI, and study centre (table 3). The impairment in HRQoL associated with the symptoms was more pronounced for PCS than for MCS.

All the symptoms except breathlessness at night were related to MCS. Breathlessness at rest and waking up with chest tightness were associated with the greatest HRQoL impairment, both in PCS and MCS (table 3).

The adjusted relationship between the symptoms and the HRQoL scores were further explored by analyses stratified by asthma and/or COPD (additional file 1). The relationship between wheeze and breathlessness and the HRQoL scores was similar, whether the subjects had asthma and/or COPD or not, with the exception of breathlessness at rest, which was significantly lower in subjects without asthma and/or COPD compared to those with any of these diagnoses. For cough and phlegm symptoms, the impairment in PCS was somewhat higher in subjects with asthma and/or COPD compared to subjects without these diseases.

Additional analyses assessing the respiratory symptoms-HRQoL relationship in those with asthma and in those with COPD separately showed that these relationships did not differ overtly between subjects with asthma and subjects with COPD (data not shown).

The results of the factor analysis are shown in table 4. Two factors were retained. Symptoms indicated in questions 1-6 (appendix 1) correlated highly and founded the basis for the factor named "wheeze or breathlessness", while questions 7-11 formed a factor for "chronic cough or phlegm". Table 4 displays the results of two multiple linear regression models with respect to PCS and MCS, with the two symptom factors as explanatory variables. Presence of symptoms related to "wheeze or breathlessness" was associated with almost twice the PCS impairment compared to presence of symptoms related to "chronic cough or phlegm". The first model was adjusted for age, gender, smoking, occupation, BMI, comorbidity, and study centre. The second was also adjusted for atopy, BHR, and FEV1. The coefficients for the symptom factors did not change significantly when adjusted for atopy, BHR, and FEV1.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first international general population study assessing the association between respiratory symptoms and HRQoL. The association between respiratory symptoms and HRQoL did not depend on having a specific diagnosis of asthma or COPD, as the association was similar in subjects with and without these diseases. Furthermore, in subjects without asthma and/or COPD, the impairment in HRQoL associated with the respiratory symptoms was neither explained by atopy, BHR, nor impairment of lung function.

HRQoL and other diseases

One of the advantages of using a general HRQoL questionnaire like the SF-36 is that it allows for comparison between different populations. In a Norwegian study where the HRQoL measured by SF-36 of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, epilepsy, angina pectoris, asthma and COPD were compared, and the patients with COPD and rheumatoid arthritis had the lowest physical scores [28]. The mean PCS of patients with COPD was 45, in other words in the same magnitude as the score decrements as the respiratory symptoms investigated in the present study. In a German study evaluating the HRQoL of patients in general practices, the adjusted mean PCS decrements of patients with COPD and asthma were 4.2 points, also comparable to the impairment of PCS scores we found in our study [29]. Our study elaborates on the association between respiratory disease and HRQoL by highlighting the importance of respiratory symptoms, and not only diagnosed disease in this association.

Chronic respiratory symptoms can be caused by other conditions than asthma and COPD. Obesity, heart diseases, hypertension with congestive heart failure, and cancer with metastasis to the lungs can have similar symptomatology. In the current study, both BMI and comorbidities were included as adjustment variables in the analyses. Of the 6009 subjects, 45.8% had no comorbidities 33.2% had one or more, and in 21.0% data on comorbidities were missing. To evaluate if the observed associations between respiratory symptoms and HRQoL could be due to residual confounding by comorbidity, the analyses presented in additional file 1 were also conducted in subjects without comorbidities. In this subgroup, there were still significant associations between respiratory symptoms and HRQoL, both in subjects with and without asthma and/or COPD (data not shown).

HRQoL, COPD, and asthma

In the current analyses, we chose to join self-reported asthma and spirometrically defined COPD in one group. Firstly, aging is an established risk factor for COPD [17, 30, 31]. The risk of developing COPD is substantially higher in subjects over 45 years of age [17] compared to younger subjects, and the majority of our study population was under 45 years. Secondly, among our study participants, 336 subjects (5.6%) had airway obstruction measured with pre-bronchodilatator spirometry, and the majority of these had FEV1 > 80% of predicted. Most likely, a large number of these subjects have reversible airway obstruction [32], indicating asthma and not COPD. Thirdly, there where 102 subjects that reported ever having had asthma in addition to having FEV1/FVC < 0.70. Thus, in a population study as this classification error between asthma and COPD is difficult to avoid. Since the main focus of the study was the subjects without obstructive lung disease, we chose to group asthma and COPD together.

A priori, respiratory symptoms without a known cause will probably be more worrying than symptoms with a recognized pathological origin. A study of asthma and COPD patients in the Netherlands showed that knowledge about both asthma and COPD was related to better adaptation to these diseases [33]. Knowledge of disease is likely to vary in the group of asthma and/or COPD in our study, since asthma was self-reported and COPD was based on spirometric measurements of airflow limitation. To account for an eventual positive effect of knowledge of disease we conducted analyses stratified by asthma and COPD. However, the HRQoL scores did not differ significantly between the subjects with self-reported asthma and respiratory symptoms and the subjects with spirometrically confirmed COPD and respiratory symptoms.

Some symptoms had a greater impact on HRQoL than other symptoms. Subjects with breathlessness without asthma and/or COPD had lower both PCS and MCS than subjects with asthma and/or COPD. It could be that breathlessness indicated by subjects without asthma or COPD represents a different sensation than in subjects with asthma and/or COPD; dyspnoea is a term describing many sensations [34], and the underlying mechanisms of dyspnoea are many [35].

Subjects with cough/phlegm symptoms and asthma/COPD had lower PCS than subjects with these symptoms and neither asthma nor COPD. This difference might be explained by the frequency and intensity of these symptoms, which most likely are higher in subjects with asthma and/or COPD. The symptom questionnaire did not assess symptom frequency and intensity, so this remains unsolved. COPD is a heterogeneous disease, and the classical way of describing the different phenotypes have been through the Snider venn diagram. Snider described the variety of obstructive lung disease is through the phenotype with asthma, the one with chronic bronchitis, the one with emphysema, and varying degrees of overlap between the three phenotypes. The hallmark symptoms of the chronic bronchitis phenotype often are cough and phlegm. The decreased PCS accompanying the cough and phlegm in our analyses of subjects with asthma and/or COPD may indicate that subjects with the chronic bronchitis phenotype have lower HRQoL than the asthma and emphysema phenotypes.

Objective measurements

When atopy, BHR and FEV1 was included in the regression model with the symptom factors, the regression coefficients did not change overtly. Garcia-Marcos et al evaluated HRQoL in asthmatic children and found that atopy was not a risk factor for decreased HRQoL [36]. We have found no previous general population studies investigating BHR in the context of HRQoL. Better lung function was related to higher HRQoL as found in another study [31], but the difference in FEV1 associated with one point change in the PCS score was more than 1000 ml. In other words, a change in PCS score barely statistically significant corresponded to five times the FEV1 change regarded as clinically relevant spirometrically.

Conclusion

Respiratory symptoms are among the more common health problems in the general population. Our results have shown that otherwise healthy young adults reporting respiratory symptoms have a relevant impairment in quality of life, which is not restricted to those with asthma or COPD and cannot be explained by atopy, reduced lung function, or BHR. Understanding the nature of these symptoms and the implications for diagnosis, treatment and prevention, remains a relevant challenge. Furthermore, our study suggests that it is important to adjust for respiratory symptoms, and not only respiratory disease or other comorbidities when HRQoL is evaluated.

Appendix 1

Wheezing or whistling in your chest in the last 12 months

If yes to 1, breathless when wheezing sound present

If yes to 1, wheezing and whistling without cold

Woken up with a feeling of chest tightness in the last 12 months

Attack of short breath after activity last 12 months

Attack of shortness of breath at rest in the last 12 months

Woken by attack of shortness of breath in the last 12 months

Woken by attack of coughing in the last 12 months

Usually cough first thing in the morning in winter?

Usually cough in day or night during winter?

7.1 Cough like this for 3 months a year?

Bring up phlegm from your chest in the morning in the winter?

Bring up phlegm during day or night in the winter?

Bring up phlegm most days for three months each year?

Ever had asthma?

Appendix 2

Suffer from long term limiting illness

Suffer with arthritis

Suffer with hypertension-high blood presure

Suffer with deafness

Suffer with varicose veins

Suffer from cataracts

Suffer from heart disease

Suffer from depression

Suffer from diabetes

Suffer from migraine/recurrent headaches

Have cancer

Had a stroke

References

Variations in the prevalence of respiratory symptoms, self-reported asthma attacks, and use of asthma medication in the European Community Respiratory Health Survey (ECRHS) Eur Respir J 1996, 9: 687–695. 10.1183/09031936.96.09040687

Eagan TM, Bakke PS, Eide GE, Gulsvik A: Incidence of asthma and respiratory symptoms by sex, age and smoking in a community study. Eur Respir J 2002, 19: 599–605. 10.1183/09031936.02.00247302

Lundback B, Stjernberg N, Nystrom L, Forsberg B, Lindstrom M, Lundback K, Jonsson E, Rosenhall L: Epidemiology of respiratory symptoms, lung function and important determinants. Report from the Obstructive Lung Disease in Northern Sweden Project. Tuber Lung Dis 1994, 75: 116–126. 10.1016/0962-8479(94)90040-X

Frostad A, Soyseth V, Haldorsen T, Andersen A, Gulsvik A: Respiratory symptoms and long-term cardiovascular mortality. Respir Med 2007, 101: 2289–2296. 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.06.023

Voll-Aanerud M, Eagan TM, Wentzel-Larsen T, Gulsvik A, Bakke PS: Respiratory symptoms, COPD severity, and health related quality of life in a general population sample. Respir Med 2008, 102: 399–406. 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.10.012

Bridevaux PO, Gerbase MW, Probst-Hensch NM, Schindler C, Gaspoz JM, Rochat T: Long-term decline in lung function, utilisation of care and quality of life in modified GOLD stage 1 COPD. Thorax 2008, 63: 768–774. 10.1136/thx.2007.093724

de Marco R, Accordini S, Cerveri I, Corsico A, Anto JM, Kunzli N, Janson C, Sunyer J, Jarvis D, Chinn S, Vermeire P, Svanes C, Ackermann-Liebrich U, Gislason T, Heinrich J, Leynaert B, Neukirch F, Schouten JP, Wjst M, Burney P: Incidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a cohort of young adults according to the presence of chronic cough and phlegm. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007, 175: 32–39. 10.1164/rccm.200603-381OC

Vestbo J, Prescott E, Lange P: Association of chronic mucus hypersecretion with FEV1 decline and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease morbidity. Copenhagen City Heart Study Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996, 153: 1530–1535.

Fujimura M, Nishizawa Y, Nishitsuji M, Nomura S, Abo M, Ogawa H: Predictors for typical asthma onset from cough variant asthma. J Asthma 2005, 42: 107–111. 10.1081/JAS-51336

Sistek D, Wickens K, Amstrong R, D'Souza W, Town I, Crane J: Predictive value of respiratory symptoms and bronchial hyperresponsiveness to diagnose asthma in New Zealand. Respir Med 2006, 100: 2107–2111. 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.03.028

Frostad A, Soyseth V, Andersen A, Gulsvik A: Respiratory symptoms as predictors of all-cause mortality in an urban community: a 30-year follow-up. J Intern Med 2006, 259: 520–529. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01631.x

Hu J, Meek P: Health-related quality of life in individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Heart Lung 2005, 34: 415–422. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2005.03.008

Polley L, Yaman N, Heaney L, Cardwell C, Murtagh E, Ramsey J, Macmahon J, Costello RW, McGarvey L: Impact of cough across different chronic respiratory diseases: comparison of two cough-specific health-related quality of life questionnaires. Chest 2008, 134: 295–302. 10.1378/chest.07-0141

Schatz M, Mosen D, Apter AJ, Zeiger RS, Vollmer WM, Stibolt TB, Leong A, Johnson MS, Mendoza G, Cook EF: Relationships among quality of life, severity, and control measures in asthma: an evaluation using factor analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005, 115: 1049–1055. 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.02.008

Schlecht NF, Schwartzman K, Bourbeau J: Dyspnea as clinical indicator in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chron Respir Dis 2005, 2: 183–191. 10.1191/1479972305cd079oa

Bednarek M, Maciejewski J, Wozniak M, Kuca P, Zielinski J: Prevalence, severity and underdiagnosis of COPD in the primary care setting. Thorax 2008, 63: 402–407. 10.1136/thx.2007.085456

Johannessen A, Omenaas E, Bakke P, Gulsvik A: Incidence of GOLD-defined chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a general adult population. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2005, 9: 926–932.

Raherison C, Abouelfath A, Le Gros V, Taytard A, Molimard M: Underdiagnosis of nocturnal symptoms in asthma in general practice. J Asthma 2006, 43: 199–202. 10.1080/02770900600566744

Voll-Aanerud M, Eagan TM, Wentzel-Larsen T, Gulsvik A, Bakke PS: Changes in respiratory symptoms and health-related quality of life. Chest 2007, 131: 1890–1897. 10.1378/chest.06-2629

Burney PG, Luczynska C, Chinn S, Jarvis D: The European Community Respiratory Health Survey. Eur Respir J 1994, 7: 954–960.

The European Community Respiratory Health Survey II Eur Respir J 2002, 20: 1071–1079. 10.1183/09031936.02.00046802

Aaronson NK, Acquadro C, Alonso J, Apolone G, Bucquet D, Bullinger M, Bungay K, Fukuhara S, Gandek B, Keller S, et al.: International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) Project. Qual Life Res 1992, 1: 349–351. 10.1007/BF00434949

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD: SF-36 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales: A User's manual. 1994. --- Either ISSN or Journal title must be supplied.

Leynaert B, Neukirch C, Liard R, Bousquet J, Neukirch F: Quality of life in allergic rhinitis and asthma. A population-based study of young adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000, 162: 1391–1396.

Pauwels RA, Buist AS, Ma P, Jenkins CR, Hurd SS: Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and World Health Organization Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD): executive summary. Respir Care 2001, 46: 798–825.

Jarvis D, Luczynska C, Chinn S, Potts J, Sunyer J, Janson C, Svanes C, Kunzli N, Leynaert B, Heinrich J, Kerkhof M, Ackermann-Liebrich U, Anto JM, Cerveri I, de Marco R, Gislason T, Neukirch F, Vermeire P, Wjst M, Burney P: Change in prevalence of IgE sensitization and mean total IgE with age and cohort. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005, 116: 675–682. 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.05.009

StataCorp Stata Statistical Software, InCollege Station, TX;

Stavem K, Lossius MI, Kvien TK, Guldvog B: The health-related quality of life of patients with epilepsy compared with angina pectoris, rheumatoid arthritis, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Qual Life Res 2000, 9: 865–871. 10.1023/A:1008993821253

Wang HM, Beyer M, Gensichen J, Gerlach FM: Health-related quality of life among general practice patients with differing chronic diseases in Germany: cross sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2008, 8: 246. 10.1186/1471-2458-8-246

Bakke PS, Baste V, Hanoa R, Gulsvik A: Prevalence of obstructive lung disease in a general population: relation to occupational title and exposure to some airborne agents. Thorax 1991, 46: 863–870. 10.1136/thx.46.12.863

Coultas DB, Mapel D, Gagnon R, Lydick E: The health impact of undiagnosed airflow obstruction in a national sample of United States adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001, 164: 372–377.

Johannessen A, Omenaas ER, Bakke PS, Gulsvik A: Implications of reversibility testing on prevalence and risk factors for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a community study. Thorax 2005, 60: 842–847. 10.1136/thx.2005.043943

Boot CR, van der Gulden JW, Vercoulen JH, van den Borne BH, Orbon KH, Rooijackers J, van Weel C, Folgering HT: Knowledge about asthma and COPD: associations with sick leave, health complaints, functional limitations, adaptation, and perceived control. Patient Educ Couns 2005, 59: 103–109. 10.1016/j.pec.2004.10.007

Simon PM, Schwartzstein RM, Weiss JW, Fencl V, Teghtsoonian M, Weinberger SE: Distinguishable types of dyspnea in patients with shortness of breath. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990, 142: 1009–1014.

Simon PM, Schwartzstein RM, Weiss JW, Lahive K, Fencl V, Teghtsoonian M, Weinberger SE: Distinguishable sensations of breathlessness induced in normal volunteers. Am Rev Respir Dis 1989, 140: 1021–1027.

Garcia-Marcos L, Carvajal Uruena I, Escribano Montaner A, Fernandez Benitez M, Garcia de la Rubia S, Tauler Toro E, Perez Fernandez V, Barcina Sanchez C: Seasons and other factors affecting the quality of life of asthmatic children. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2007, 17: 249–256.

Acknowledgements

The coordination of ECRHS II was supported by the European Commission, as part of their Quality of Life programme. The following bodies funded the local studies in ECRHS II in this article.

Albacete -- Fondo de Investigaciones Santarias (grant code: 97/0035-01, 13 99/0034-01, and 99/0034-02), Hospital Universitario de Albacete, Consejeria de Sanidad. Antwerp -- FWO (Fund for Scientific Research)- Flanders Belgium (grant code: G.0402.00), University of Antwerp, Flemish Health Ministry.

Barcelona -- Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias (grant code: 99/0034-01, and 99/0034-02), Red Respira (RTIC 03/11 ISC IIF). Ciber of Epidemiology and Public Health has been established and founded by Instituto de Salud Carlos III.

Basel -- Swiss National Science Foundation, Swiss Federal Office for Education & Science, Swiss National Accident Insurance Fund (SUVA).

Bergen--Norwegian Research Council; Norwegian Asthma & Allergy Association (NAAF); Glaxo Wellcome AS, Norway Research Fund.

Bordeaux--Institut Pneumologique d'Aquitaine.

Erfurt--GSF-National Research Centre for Environment & Health, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (grant code FR 1526/1-1).

Galdakao--Basque Health Department.

Gothenburg--Swedish Heart Lung Foundation, Swedish Foundation for Health Care Sciences & Allergy Research, Swedish Asthma & Allergy Foundation, Swedish Cancer & Allergy Foundation.

Grenoble--Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique-DRC de Grenoble 2000 no. 2610, Ministry of Health, Direction de la Recherche Clinique, Ministere de l'Emploi et de la Solidarite, Direction Generale de la Sante, CHU de Grenoble, Comite des Maladies Respiratoires de l'Isere.

Hamburg--GSF-National Research Centre for Environment & Health, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (grant code MA 711/4-1).

Ipswich and Norwich--National Asthma Campaign (UK).

Huelva--Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias (FIS) (grant code: 97/0035-01, 99/0034-01, and 99/0034-02).

Montpellier--Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique-DRC de Grenoble 2000 no. 2610, Ministry of Health, Direction de la Recherche Clinique, CHU de Grenoble, Ministere de l'Emploi et de la Solidarite, Direction Generale de la Sante, Aventis (France), Direction Régionale des Affaires Sanitaires et Sociales Languedoc-Roussillon. Oviedo--Fondo de Investigaciones Santarias (FIS) (grant code: 97/0035-01, 99/0034-01, and 99/0034-02).

Paris--Ministere de l'Emploi et de la Solidarite, Direction Generale de la Sante, UCBPharma (France), Aventis (France), Glaxo France, Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique-DRC de Grenoble 2000 no. 2610, Ministry of Health, Direction de la Recherche Clinique, CHU de Grenoble.

Pavia--Glaxo, Smith & Kline Italy, Italian Ministry of University and Scientific and Technological Research (MURST), Local University Funding for Research 1998 & 1999 (Pavia, Italy).

Portland--American Lung Association of Oregon, Northwest Health Foundation, Collins Foundation, Merck Pharmaceutical.

Reykjavik--Icelandic Research Council, Icelandic University Hospital Fund.

Tartu--Estonian Science Foundation.

Turin--ASL 4 Regione Piemonte (Italy), AO CTO/ICORMA Regione Piemonte (Italy), Ministero dell'Università e della Ricerca Scientifica (Italy), Glaxo Wellcome spa (Verona, Italy).

Umeå--Swedish Heart Lung Foundation, Swedish Foundation for Health Care Sciences & Allergy Research, Swedish Asthma & Allergy Foundation, Swedish Cancer & Allergy Foundation.

Uppsala--Swedish Heart Lung Foundation, Swedish Foundation for Health Care Sciences & Allergy Research, Swedish Asthma & Allergy Foundation, Swedish Cancer & Allergy Foundation.

Verona--University of Verona; Italian Ministry of University and Scientific and Technological Research (MURST); Glaxo, Smith & Kline Italy.

The following bodies funded ECRHS I for centres in ECRHS II:

Belgian Science Policy Office, National Fund for Scientific Research; Ministère de la Santé, Glaxo France, Institut Pneumologique d'Aquitaine, Contrat de Plan Etat-Région Languedoc-Rousillon, CNMATS, CNMRT (90MR/10, 91AF/6), Ministre delegué de la santé, RNSP, France; GSF, and the Bundesminister für Forschung und Technologie, Bonn, Germany; Ministero dell'Università e della Ricerca Scientifica e Tecnologica, CNR, Regione Veneto grant RSF n. 381/05.93, Italy; Norwegian Research Council project no. 101422/310; Dutch Ministry of Wellbeing, Public Health and Culture, Netherlands; Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo FIS (grants #91/0016060/00E-05E and #93/0393), and grants from Hospital General de Albacete, Hospital General Juan Ramón Jiménez, Consejería de Sanidad, Principado de Asturias, Spain; The Swedish Medical Research Council, the Swedish Heart Lung Foundation, the Swedish Association against Asthma and Allergy; Swiss National Science Foundation grant 4026-28099; National Asthma Campaign, British Lung Foundation, Department of Health, South Thames Regional Health Authority, UK; United States, Department of Health, Education and Welfare Public Health Service (grant #2 S07 RR05521-28).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

Authors MVA, TMLE, EP, ERO, CS, VS, IP, JMA, and BL have no conflicts of interest.

Within the last 5 years MVA, TMLE, and PSB have received sponsorship for travel and accommodation to the ATS conference from GlaxoSmithKline, and TMLE has received grant monies from AstraZeneca. PSB has received 2000 € in lecture fees from GlaxoSmithKline and 1000 € in lecture fees from AstraZeneca during the last 5 years. PSB acts as a principle investigator in the ECLIPSE study. None of this is related to the present study.

Authors' contributions

The presented work is carried out in collaboration between all authors. JMA and MVA defined the research theme. JMA, CS, ERO, and BL designed the data collection. EP and MVA conducted the statistical analyses. Results interpreted by JMA, EP, and MVA. All authors contributed to the drafting and critical revising of the manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12955_2010_730_MOESM1_ESM.DOC

Additional file 1: Association (coefficient and 95% CI) of the physical component summary (PCS) and the mental component summary (MCS) with respiratory symptoms in the ECRHS II by asthma and/or COPD, adjusted for age, gender, smoking, comorbidity, and country. (DOC 82 KB)

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Voll-Aanerud, M., Eagan, T.M., Plana, E. et al. Respiratory symptoms in adults are related to impaired quality of life, regardless of asthma and COPD: results from the European community respiratory health survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes 8, 107 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-8-107

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-8-107