Abstract

Objectives

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a prevalent psychiatric disorder associated with impaired patient functioning and reductions in health-related quality of life (HRQL). The present study describes the impact of MDD on patients' HRQL and examines preference-based health state differences by patient features and clinical characteristics.

Methods

95 French primary care practitioners recruited 250 patients with a DSM-IV diagnosis of MDD for inclusion in an eight-week follow-up cohort. Patient assessments included the Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), the Clinical Global Impression of Severity (CGI), the Short Form-36 Item scale (SF-36), the Quality of Life Depression Scale (QLDS) and the EuroQoL (EQ-5D).

Results

The mean EQ-5D utility at baseline was 0.33, and 8% of patients rated their health state as worse than death. There were no statistically significant differences in utilities by demographic features. Significant differences were found in mean utilities by level of disease severity assessed by CGI. The different clinical response profiles, assessed by MADRS, were also revealed by EQ-5D at endpoint: 0.85 for responders remitters, 0.72 for responders non-remitter, and 0.58 for non-responders. Even if HRQL and EQ-5D were moderately correlated, they shared only 40% of variance between baseline and endpoint.

Conclusions

Self-reported patient valuations for depression are important patient-reported outcomes for cost-effectiveness evaluations of new antidepressant compounds and help in further understanding patient compliance with antidepressant treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is common in primary care patients [1] with a lifetime prevalence rate in the French population of 10–25% in women and 5–12% in men [2]. Depression is associated with marked decreases in functioning, well being and health-related quality of life (HRQL) [3, 4], and an increases in disability days [5], use of health services and overall societal costs [6]. Antidepressant treatments are effective in reducing depression severity [7, 8] and in increasing patient functioning and HRQL [9, 10].

The Washington Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine recommended the use of HRQL in the evaluation of health care interventions [11]. For this purpose, HRQL measurement needs to express patient health status on a scale where perfect health and death are valued 1 and 0 respectively. When such quality of life data are combined with corresponding data on the quantity of life, then the consequences of treatment are measured in units of Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALYs) [12]. Where QALYs are calculated for social decision making purposes then the HRQL measures used to make the quality adjustment should be based on the preferences of the population as a whole. Such social preferences are only available for a limited number of HRQL measures and for a limited number of countries. EQ-5D is one such measure that has been calibrated in this way.

Studies of physical illnesses have suggested that patient's values for their own health state affect decisions concerning treatment and its outcomes [13–15]. Several studies focused on establishing utility scores for a variety of health states in various mental illnesses, including schizophrenia [16], depression in primary care [17], temporary states of depression [18, 19] and treatment-related side effects [20, 21]. Health states in depression have been characterised by the presence or absence of symptoms, and depressed patients are usually categorised as responders and remitters using classical rating scales [22]. As responders sometimes present residual depressive symptoms, we classify patients as "Responder remitters", "Responders non-remitter" and "Non-responders".

The objectives of this paper are to describe the impact on HRQL of patients with MDD treated in a primary care setting, and to examine variations in terms of patients' demographic and clinical characteristics.

Material and methods

Design and patient sample

This national, multicentre, prospective, non-comparative cohort study was designed so as to reproduce the guidelines for management of depression in primary care. The scheduled follow-up period was two months, with assessments at baseline (D0), four weeks later (D28) and eight weeks later (D56).

The patients included in this study were recruited from an outpatient population, aged 18 and older, who consulted general practitioners for a new episode of MDD according to the DSM-IV [23]), and who were not treated with any antidepressant before inclusion. Patients whose symptomatology suggested schizophrenia or other psychotic symptoms, according to DSM-IV, were not included in this study. According to their experience and daily practice, general practitioners initiated an antidepressant treatment at baseline.

Data collection

Patients' characteristics

Patient profiles were created at baseline by recording age, gender, lifestyle, place of residence, socio-professional category and current professional status.

Clinical measures

Physicians assessed the severity of depressive symptoms using the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) [24] and the Clinical Global Impression of Severity (CGI-S) scale. The CGI was rated by physicians on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = "Normal, not ill at all" to 7 = "Among the most ill patients".

Qualitative outcomes derived from rating scales, like response to treatment or remission, are usually used in both clinical trials and economic evaluations of new antidepressant agents [22]. Using MADRS scores at D56, patients were classified into two groups: those that had scores lower or equal to 12 were considered as "Remitters", the others were considered as "Non-remitters". Patients who had a decrease of at least 50% in relation to baseline score were considered as "Responder", whereas the others were "Non-responders". These two patients groupings led to the creation of three mutually exclusive groups: "Responder remitters", "Responders non-remitter" and "Non-responders".

Patient Reported Outcomes

The outcome measures used in this study were the 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36), the Quality of Life in Depression Scale (QLDS) and the EQ-5D.

The SF-36 is a generic HRQL measure consisting of eight dimensions assessing physical functioning (PF), role limitations due to physical problems (RP), bodily pain (BP), general health (GH), vitality (VT), mental health (MH), role limitations due to emotional problems (RE) and social functioning (SF) [25]. Two summary scores also assess both physical (PCS) and mental (MCS) facets [26]. All scale scores range from 0 (the worst HRQL) to 100 (the best HRQL).

The QLDS is a 34-item depression-specific HRQL instrument that assesses the ability and capacity of individuals to satisfy their daily needs [27, 28]. Each item is answered by Yes or No. An overall HRQL score is obtained by summing the 34 items. The results range from 0 (the highest HRQL) to 34 (the lowest HRQL).

EQ-5D is a generic measure of HRQL in which health status is defined in terms of 5 dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression [29]. Each dimension has three qualifying levels of response roughly corresponding to 'no problems', 'some difficulties/problems', and 'extreme difficulties'. EQ-5D defines a total of 243 unique health states. The importance of each of these states can be determined in a number of different ways. For the purpose of cost-utility analysis and other situations where the consequences of treatment are measured in terms of QALYs, these weights are typically established using utility measurement techniques such as Standard Gamble or Time Trade-Off (TTO) [12]. For the purposes of this present study, TTO weights elicited from a large national survey of the UK population were used [30]. Information collected using EQ-5D can be reported in terms of its individual dimensions and as a single index score (EQ-5DST).

Data analysis

Continuous variables were expressed by means and standard deviations, whereas categorical data were presented using frequency and percentage. The scales were scored using scoring algorithms described by the scale designers. Student's t-tests, ANOVA, Mann-Whitney, or Kruskal-Wallis tests were performed when appropriate to compare mean scores across subgroups. Regression analyses were used to examine the relationships between differences in the utility-weighted EQ-5DST and demographics, clinical response and HRQL measures. Several selection procedures (backward, stepwise) were tested in order to check the robustness of the model. The impact of each predictor was assessed with estimates and their 95% confidence interval. The data were analysed using the SAS software version 8.2. For all tests, the type I error was set to 0.05.

Results

Sample characteristics

Ninety-five physicians enrolled 250 patients between May and November 2002. Patient age ranged from 18 to 92 years, with a mean of 44.2 ± 14.1 years (mean ± standard deviation). The sex ratio (males/females) was 0.4. The mean MADRS score was 32.7 ± 7.7, ranging from 13 to 53. This high level of severity was also revealed by the CGI: about 85% of patients were rated "markedly ill" or more severely. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are reported in Table 1.

Among the 250 included patients, 24 were lost to follow-up (9.6%). Their sociodemographics and clinical characteristics were not significantly different from those of the 226 completers, so that all subsequent analyses were performed on the completers sub-sample.

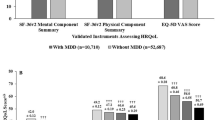

Impact of MDD on HRQL

At baseline, the mean QLDS score was 20.8 ± 5.8, ranging from 5 to 31. The mean SF-36 dimension scores for the total sample were: PF 69.0 ± 24.5, RP 22.4 ± 30.7, BP 52.0 ± 23.5, GH 38.3 ± 17.3, VT 22.2 ± 13.1, MH 24.5 ± 12.1, RE 9.1 ± 21.3 and SF 30.2 ± 17.1. The mean SF-36 summary scores were PCS 43.6 ± 9.2 and MCS 21.1 ± 6.6. The mean EQ-5DST score was 0.33 ± 0.25, ranging between -0.59 and 0.85. It was noteworthy that 8% of the study population had an EQ-5DST score of worse than death, i.e. less than zero.

During follow-up, all the dimensions rated improved (Table 2). The mean EQ-5DST scores were 0.68 ± 0.24 (range: [-0.11; 1.00]) and 0.78 ± 0.21 (range: [-0.08; 1.00]) at weeks 4 and 8, respectively.

Comparison of EQ-5DST by demographic and clinical features

No significant differences were found in EQ-5DST by demographics characteristics (Table 3): men and women reported the same preference-based score at baseline (0.32 ± 0.22 vs. 0.32 ± 0.26, respectively) and their scores increased in a similar manner during follow-up. Younger patients reported higher utility scores than older patients at baseline, day 28 and day 56, although this pattern was not statistically significant.

Significant differences in EQ-5DST were found by disease severity level assessed by CGI-S, with more severe patients having lower weighted index scores. At baseline, a mean difference of 0.12 was observed between "slightly/moderately ill" and "markedly ill" patients (p < 0.05), and 0.18 between "markedly ill" and "seriously ill" patients (p < 0.001). At the end of the follow-up, a mean difference of 0.12 was observed between patients with "first signs of illness" and "slightly/moderately ill" patients (p < 0.001). "Slightly/moderately ill" and "markedly ill" patients had EQ-5DST scores that differed 0.30 on average (p < 0.001). A mean difference of 0.14 between "markedly ill" patients and "seriously ill" patients was found (p < 0.05).

Comparison of EQ-5DST by clinical response

Clinical response, defined by MADRS scores, revealed statistically significant differences between mean EQ-5DST scores at baseline (p < 0.01), D28 (p < 0.001) and D56 (p < 0.001) (Table 4).

At baseline, an overall significant difference was found in comparing the three groups, with a mean difference of 0.14 observed between "Responder remitters" and "Responder non-remitters" (p < 0.01). During the study period, EQ-5DST scores increased in all groups of clinical response. At the end of the follow-up, a statistically significant mean difference of 0.14 was observed between "Responder remitters" and "Responders non-remitter" (p < 0.001). "Responders non-remitter" and "Non-responders" had EQ-5DST scores that significantly differed by 0.14 on average (p < 0.05).

Comparison of Patient Reported Outcomes

At each visit, EQ-5DST scores were compared with SF-36 dimension, SF-36 summary and QLDS scores (Table 5) by computing correlation coefficients. The correlation between EQ-5DST score and the Mental Health dimension of the SF-36 was the highest observed, whatever the assessment (DO: r = 0.49; D28: r = 0.56; D56: r = 0.63). At baseline, Pearson correlation coefficients were always greater than 0.30, except for the role-physical and role-emotional dimensions.

The QLDS was significantly correlated with the EQ-5DST scores, ranging from -0.43 at baseline to -0.68 at the end of the follow-up period.

Multivariate analysis

An ordinary least-square regression analysis to predict EQ-5DST using demographic features, clinical and HRQL evolution only explained 40% of the variance in the weighted index scores. The statistically significant predictors in the regression model were differences in Physical Functioning, Bodily Pain, General Health and Mental Health (Table 6).

Discussion

This study evaluated the usefulness of EQ-5D in assessing health status of primary care patients with major depressive disorder.

The sampling of our study is representative of the primary care depressed population in France [2]. 8% of the patients rated their health state as worse than death. This result is not surprising given the relationship between depression and suicide [31, 32]. Despite different approaches to measuring health state utilities using standard gamble, time trade-off or rating scales, the findings of our study agree with those previously reported: the baseline mean utility of an untreated depression was 0.33, compared to 0.30 for Revicki [21] and 0.32 for Bennett [33]. Patient-rated EQ-5DST scores after the eight-week follow-up period was 0.78, which is comparable to utilities reported in other studies (0.79 [33]; 0.74 [21]; 0.76 [34]; 0.70 [35]). The main interest is that EQ-5DST values are easy to collect in large sample surveys due to the brevity of EQ-5D classification system with its 5 dimensions and 3 levels.

No differences in EQ-5DST utilities were observed by demographic characteristics, which is comparable to previous results in depressed patients [21, 34, 35]. More severely depressed patients reported utilities that were 0.30 points lower than less severely depressed patients at baseline. Several researchers have suggested that differences in utility greater than 0.05 are clinically important [12, 36]. These findings may reflect clinically important differences.

As demonstrated in previous studies [21, 37], we found that the EQ-5DST score and other HRQL measures shared only about 40% of variance. Utilities measure a patient's preference for their health state, while HRQL scales assess the patient's report of their functioning and well-being. Although these two concepts are related they are not identical [38], and measuring both may lead to a better understanding of reasons for non-compliance to treatment regimens.

There are several limitations that need to be considered when interpreting the results of this study. First, the study does not take into account the antidepressant prescribed or their side effects, which may influence patients' ratings [21, 39]. Second, the concomitant impact of depression and chronic medical conditions could not be examined in this sample. It is likely that the health state utilities of patients with depression, in addition to a chronic medical disease would be significantly reduced [17]. Lastly, a limitation of the analysis presented in this study relates to the source of the utility weights used to compute the EQ-5DST. Given that this was a national study conducted in France it may have been better to use social preference values based on the French population. Unfortunately, at the time of writing these values were not available for EQ-5DST. Weights were therefore adopted from a major UK study that provided the most robust technical estimates widely used in the evaluation of EQ-5DST in countries that lack their own national reference data.

Utility scores are needed for calculating QALYs, which are used as indicators of effectiveness or outcome in economic evaluations [35, 36, 40]. It is debatable whether or not patient or general population utilities should be used in cost-effectiveness studies [40]. Nevertheless, patients with experience in the disease may be the best providers of health state preference data. Cost-effectiveness studies are required to help clinicians and health care decision-makers in determining the impact of new antidepressants on both patient outcomes and medical or overall societal costs. Understanding patient preferences for depression outcomes is important for economic evaluations of new antidepressants, as well as for understanding patient behaviour and compliance to antidepressant regimens. Such a measure can be applied to cost-utility analyses either within clinical decision modelling studies or within prospective, randomised clinical trials and offers additional scope for the analysis and reporting of data derived from clinical trials of new compounds.

References

Williams JW Jr, Kerber CA, Mulrow CD, Medina A, Aguilar C: Depressive disorders in primary care: prevalence, functional disability and identification. J Gen Intern Med 1995, 10: 7–12.

Le Pape A, Lecomte T: Prévalence et prise en charge de la dépression. Paris: Centre de Recherche en Economie de la Santé 1999.

Hays RD, Wells KB, Sherbourne CD, Rogers W, Spritzer K: Functioning and well-being outcomes of patients with depression compared with chronic general medical illnesses. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995, 52: 11–9.

Saarijarvi S, Salminen JK, Toikka T, Raitasalo R: Health-related quality of life among patients with major depression. Nord J Psychiatry 2002, 56: 261–4. 10.1080/08039480260242741

Lecrubier Y: The burden of depression and anxiety in general medicine. J Clin Psychiatry 2001, 62: 4–9.

Goff VV: Depression: a decade of progress, more to do. NHPF Issure Brief 2002, 786: 1–14. (Nov 22)

Nierenberg AA: Current perspectives on the diagnosis and treatment of major depressive disorder. Am J Manag Care 2001, 7: S353–66.

Brown C, Schulberg HC, Prigerson HG: Factors associated with symptomatic improvement and recovery from major depression in primary care patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2000, 22: 242–50. 10.1016/S0163-8343(00)00086-4

Revicki DA, Simon GE, Chan K, Katon W, Heiligenstein J: Depression, health-related quality of life, and medical cost outcomes of receiving, recommended levels of antidepressant treatment. J Fam Pract 1998, 47: 446–52.

Reynolds CF 3rd: Treatment of major depression in late life: a life cycle perspective. Psychiatr Q 1997, 68: 221–46. 10.1023/A:1025484123244

Weinstein MC, Siegel JE, Gold MR, Kamlet MS, Russell LB: Recommendations of the Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. JAMA 1996, 276: 1253–8. 10.1001/jama.276.15.1253

Bennett KJ, Torrance GW: Measuring health state preferences and utilities: rating scale, time trade-off and standard gamble techniques. In: Quality of Life and Pharmacoeconomics in Clinical Trials 2 Edition (Edited by: Spilker B). Philadelphia: Lipincott-Raven 1996.

de Boer AG, Stalmeier PF, Sprangers MA, de Haes JC, van Sandick JW, Hulscher JB, van Lanschot JJ: Transhiatal vs extended transthoracic resection in oesophageal carcinoma: patients' utilities and treatment preferences. Br J Cancer 2002, 86: 851–7. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600203

Tosteson AN, Hammond CS: Quality-of-life assessment in osteoporosis: health-status and preferenced-based measures. Pharmacoeconomics 2002, 20: 289–303.

Smith DS, Krygiel J, Nease RF Jr, Sumner W 2nd, Catalona WJ: Patient preferences for outcomes associated with surgical management of prostate cancer. J Urol 2002, 167: 2117–22. 10.1097/00005392-200205000-00042

Chouinard G, Albright PS: Economic and health state utility determinations for schizophrenic patients treated with risperidone or haloperidol. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1997, 17: 298–307. 10.1097/00004714-199708000-00010

Wells KB, Sherbourne CD: Functioning and utility for current health status of patients with depression or chronic medical conditions in managed, primary care practices. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999, 56: 897–904. 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.897

Bennett KJ, Torrance GW, Boyle MH, Guscott R: Cost-utility analysis in depression: the McSad utility measure for depression health state. Psychiatr Serv 2000, 51: 1171–6. 10.1176/appi.ps.51.9.1171

Schaffer A, Levitt AJ, Hershkop SK, Oh P, MacDonald C, Lanctot K: Utility scores of symptom profiles in major depression. Psychiatry Res 2002, 110: 189–97. 10.1016/S0165-1781(02)00097-5

Lenert LA, Morss S, Goldstein MK, Bergen MR, Faustman WO, Garber AM: Measurement of the validity of utility elicitations performed by computerized interview. Med Care 1997, 35: 915–20. 10.1097/00005650-199709000-00004

Revicki DA, Wood M: Patient-assigned health state utilities for depression-related outcomes: differences by depression severity and antidepressant medications. J Affect Disord 1998, 48: 25–36. 10.1016/S0165-0327(97)00117-1

Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products: Note for Guidance on Clinical Assessment of Medicinal Products in the Treatment of Depression. London: EMEA 2002.

American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association 4 Edition 1994.

Montgomery SA, Asberg M: A New Depression Scale Designed to be Sensitive to Change. Br J Psychiatry 1979, 134: 382–9.

Leplège A, Ecosse E, Verdier A, Perneger TV: The French SF-36 Health Survey: translation, cultural adaptation and preliminary psychometric evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol 1998, 51: 1013–23. 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00093-6

Ware JE Jr, Gandek B, Kosinski M, Aaronson NK, Apolone G, Brazier J, Bullinger M, Kaasa S, Leplège A, Prieto L, Sullivan M, Thunedborg K: The equivalence of SF-36 summary health scores estimated using standard and country-specific algorithms in 10 countries. J Clin Epidemiol 1998, 51: 1167–70. 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00108-5

Hunt SM, McKenna SP: The QLDS, a scale for the measurement of quality of life in depression. Health Policy 1992, 22: 307–19. 10.1016/0168-8510(92)90004-U

McKenna SP, Doward LC, Kohlmann T, Mercier C, Niero M, Paes M, Patrick D, Ramirez N, Thorsen H, Whalley D: International development of the Quality of Life in Depression Scale (QLDS). J Affect Disord 2001, 63: 189–99. 10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00184-1

EuroQoL Group: EuroQoL – a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990, 16: 199–208. 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9

Dolan P, Gudex C, Kind P, Williams A: A social tariff for EuroQoL: Results from a UK General Population Survey. University of York: Center for Health Economics 1995.

Kohn Y, Zislin J, Agid O, Hanin B, Troudard T, Shapira B, Bloch M, Gur E, Ritsner M, Lerer B: Increased prevalence of negative life events in subtypes of major depressive disorder. Compr Psychiatry 2001, 42: 57–63. 10.1053/comp.2001.19753

Angst J, Angst F, Stassen HH: Suicide risk in patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1999, 60: 57–62.

Bennett KJ, Torrance GW, Boyle MH, Guscott R, Moran LA: Development and testing of a utility measure for major, unipolar depression (McSad). Qual Life Res 2000, 9: 109–20. 10.1023/A:1008952602494

Pyne JM, Patterson TL, Kaplan RM, Ho S, Gillin JC, Goldshan S, Grant I: Preliminary longitudinal assessment of quality of life in patients with major depression. Psychopharmacol Bull 1997, 33: 23–9.

Pyne JM, Patterson TL, Kaplan RM, Gillin JC, Koch WL, Grant I: Assessment of quality of life of patients with major depression. Psychiatr Serv 1997, 48: 224–30.

Torrance GW, Feeny D: Utilities and quality-adjusted life years. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 1989, 5: 559–75.

Revicki DA, Kaplan RM: Relationship between psychometric and utility-based approaches to the measurement of health-related quality of life. Qual Life Res 1993, 2: 477–87.

Apolone G, De Carli G, Brunetti M, Garattini S: Health-related quality of life (HR-QOL) and regulatory issues. An assessment of the EMEA recommendations on the use of HR-QOL measures in drug approval. Pharmacoeconomics 2001, 19: 187–95.

Simon GE, VonKorff M, Heiligenstein JH, Revicki DA, Grothaus L, Katon W, Wagner EH: Initial antidepressant choice in primary care: effectiveness and cost of fluoxetine versus tricyclic antidepressants. JAMA 1996, 275: 1897–902. 10.1001/jama.275.24.1897

Gold MR, Siegal JE, Russell LB, Weinstein MC, eds: Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. New York: Oxford University Press 1996.

Acknowledgment

Funding for this study was provided by H. Lundbeck A/S.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Sapin, C., Fantino, B., Nowicki, ML. et al. Usefulness of EQ-5D in Assessing Health Status in Primary Care Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2, 20 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-2-20

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-2-20