Abstract

Background

Self-reported outcome instruments in health research have become increasingly important over the last decades. Occupational therapy interventions often focus on occupational balance. However, instruments to measure occupational balance are scarce. The aim of the study was therefore to develop a generic self-reported outcome instrument to assess occupational balance based on the experiences of patients and healthy people including an examination of its psychometric properties.

Methods

We conducted a qualitative analysis of the life stories of 90 people with and without chronic autoimmune diseases to identify components of occupational balance. Based on these components, the Occupational Balance-Questionnaire (OB-Quest) was developed. Construct validity and internal consistency of the OB-Quest were examined in quantitative data. We used Rasch analyses to determine overall fit of the items to the Rasch model, person separation index and potential differential item functioning. Dimensionality testing was conducted by the use of t-tests and Cronbach’s alpha.

Results

The following components emerged from the qualitative analyses: challenging and relaxing activities, activities with acknowledgement by the individual and by the sociocultural context, impact of health condition on activities, involvement in stressful activities and fewer stressing activities, rest and sleep, variety of activities, adaptation of activities according to changed living conditions and activities intended to care for oneself and for others. Based on these, the seven items of the questionnaire (OB-Quest) were developed. 251 people (132 with rheumatoid arthritis, 43 with systematic lupus erythematous and 76 healthy) filled in the OB-Quest. Dimensionality testing indicated multidimensionality of the questionnaire (t = 0.58, and 1.66 after item reduction, non-significant). The item on the component rest and sleep showed differential item functioning (health condition and age). Person separation index was 0.51. Cronbach’s alpha changed from 0.38 to 0.57 after deleting two items.

Conclusions

This questionnaire includes new items addressing components of occupational balance meaningful to patients and healthy people which have not been measured so far. The reduction of two items of the OB-Quest showed improved internal consistency. The multidimensionality of the questionnaire indicates the need for a summary of several components into subscales.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The use of self-reported outcome instruments in health care research has become increasingly important over the last decades, because the perspective of patients is an essential part regarding the effectiveness or non-effectiveness of a treatment[1–3]. Currently, it is recommended not only to measure outcomes from the perspectives of the patients, but also to involve them into the development of instruments. Patients should be asked for feedback on the wording to detect problems of understanding. Additionally, for already existing instruments, qualitative research is suitable in facilitating that the items are relevant to the target population[4–6].

Occupational balance largely guides the clinical practice of occupational therapists[7, 8]. "Occupations" refer to goal-directed, meaning- and purposeful everyday activities that people do as individuals and in their social contexts[7]. Occupational therapists focus on occupations as a means, but also as an outcome of therapy. Occupational balance is one important construct that links – in the view of occupational therapists – "occupation" and health[9, 10].

Occupational balance is defined diversely. One definition which is grounded in the beginning of occupational therapy refers to a balance between different occupational areas, such as work, play, rest and sleep[7]. However, the definitions are mainly derived from the perspectives of occupational therapists rather than of the perspectives of patients and healthy people (without a diagnosed health condition)[11]. Occupational balance may thus be an "academically defined concept" which lacks a link to the experiences of "real" people.

Up to now, only one questionnaire exists (Wilcock’s two-page "questionnaire on involvement in physical, mental, social and rest occupations") which was developed and used to assess occupational balance[12]. However, this questionnaire has not been developed based on qualitative data, and was not used in further research. One essential aspect of the validity of an instrument is the content validity, referring to its ability to measure those underlying components of the construct which it intends to measure. This requires a conceptual definition of the construct to be measured and a specification of its components[13]. To assess occupational balance in patients of different health conditions, a generic self-reported outcome instrument, based on qualitative data on the perspectives and experiences of patients and healthy people, is required. Additionally, reliable and valid (occupational balance) instruments are prerequisites for the evaluation of outcomes in occupational therapy practice.

Therefore, the aim of the study was to develop a generic self-reported outcome instrument to assess occupational balance based on the experiences of patients and healthy people including an examination of its psychometric properties.

Methods

Design

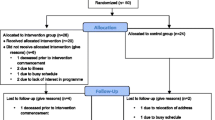

We conducted a mixed-methods study that started off with qualitative analyses of the life stories of people with and without chronic autoimmune diseases to identify components of occupational balance. Based on these components, we developed the Occupational Balance-Questionnaire (OB-Quest). A German version was designed first and then forward and back translated into English according to standard translation procedures[14]. Construct validity and internal consistency of the OB-Quest were examined in quantitative data using Rasch analyses and Cronbach’s alpha. This study was part of a larger study, the Gender, Occupational Balance and Immunology (GOBI) study[15]. A flow chart is depicted in Figure 1.

Participants

Patients of two outpatient clinics of the Medical University of Vienna, Austria, diagnosed with Crohn’s disease (CD)[16], rheumatoid arthritis (RA)[17], systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)[18], systemic sclerosis (SSc)[19] or diabetes mellitus type one (T1D)[20] were asked to participate. Only the qualitative data from patients with CD and RA were used from previous studies which employed the same methodological approach[11, 15, 21]. Additionally, healthy people were asked to participate via personal invitation by patients, such as "friends" of a similar age, and announcements in public places such as supermarkets, universities and the general hospital. Sex, age, employment status and health condition, if applicable were recorded. Furthermore, information about disease duration was obtained from patient files where appropriate.

A qualitative analysis of life stories with relation to occupational balance

A biographical narrative approach was used to explore the experience of occupational balance. The participants’ own perspectives on their lives, expressed in their life stories, were investigated in relation to current and biographic experiences[22]. The life stories, collected in two interview sessions, were transcribed verbatim and analysed with the biographic narrative interpretative method[22]. With this method, we compered the "lived life" (the biographical data) to the "told story" (the present perspective of the interviewee on her or his life). Hypotheses were developed by a research panel which were then verified or falsified depending on the course of each life story. Through this process, so-called typologies, which were common themes found in more than one life story, were identified. Typologies related to occupational balance were then extracted, defined as components of occupational balance and used as basis for the development of the questionnaire items.

Item development

Each component resulted in one item. Items were generated by the first author in collaboration with patients and healthy people[4]. After this initial process a final version of the items was formulated based on the feedback of additional patients and healthy people and on the discussion of the research panel (TAS, BP, AB and MD). Patients from the rheumatology outpatient clinic and internal medicine ward, as well as healthy people ("friends" of a similar age and visitors) were invited to give feedback. Each item included a numerical rating scale consisting of three response categories. "1" indicated a positive score, such as "having a good variety of activities", and "3" indicated a negative score such as "having little or no variety of activities". In addition, a German version was designed first and then the English version was developed by the use of a standard methodology with forward and back translation and proof reading by a total of four English or German native speakers (PG, AJ, LL and VN-D)[14].

Examination of construct validity and internal consistency

Construct validity and internal consistency of the OB-Quest were explored. Therefore, patients with RA or SLE and healthy people completed the OB-Quest, as well as a questionnaire on demographic data. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS)[23] was used for descriptive and RUMM 2030[24] for Rasch analyses. Concerning construct validity we examined overall fit of the items to the Rasch model as suggested by Tennant et al.[25]. Therefore, the mean item log residual test of fit as well as the item-trait interaction chi-square statistics were assessed[25]. Non-significant residuals between -2.5 and +2.5 were interpreted as item fit, non-significant item-trait interaction chi-square values as overall fit[25–27]. Additionally, we calculated potential differential item functioning (DIF) of sex, age (above and below the median) and health condition (RA, SLE and healthy) concerning construct validity. Furthermore, we used an approach for unidimensionality testing proposed by Smith[28], namely the combination of principal component analysis (PCA) followed by a series of t-tests to assess if subsets of items result in different estimates of person parameters. As prerequisites for the t-tests, "easy" and "hard" subsets of items were selected based on PCA. The sets of items whose residual factors loaded most strongly (positively or negatively) on the first principal component factor were used because these are most likely to violate the assumption of unidimensionality. Easy items were defined as having fit residuals that loaded negatively on the first component[29]. We used Bonferroni adjustment for multiple testing regarding the level of significance of the results of the Rasch analyses. Internal consistency is an estimate of an instruments’ reliability and was assessed with Cronbach’s alpha (α) and Rasch reliability statistics (person separation index, PSI). PSI refers to the reproducibility of relative measure location. A high PSI value (≥ 0.7) is preferred, since this indicates a high probability that people with enhanced performance will achieve high measures (sensitivity) and vice versa[30, 31]. We interpreted Cronbach’s α of ≥ 0.9 as excellent, ≤ 0.89 and ≥ 0.8 as good, ≤ 0.79 and ≥ 0.7 as acceptable and ≤ 0.69 and ≥ 0.6 as questionable[23].

Ethical considerations

Participants were informed about study procedures, and confirmed their voluntary participation with written and oral informed consents. Furthermore, we guaranteed confidentiality and changed the names in the given quotes. Approval of the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Vienna, Austria, was obtained.

Results

Participants

Ninety people participated in the qualitative part of this study (15 people each with CD, SLE, SSc, RA or T1D and 15 healthy people). The data of 251 people (132 people with RA, 43 with SLE and 76 healthy people) were collected in the quantitative part of this study. Demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

Components of occupational balance

Eight components of occupational balance were identified in the analysis of the qualitative data, as described in Table 2 in the left column. In the following we give one example of how the components relate to the transcribed data. Sabine was diagnosed with systemic sclerosis at the age of 59 years. Sabine maintained occupational balance through a balance of challenging and relaxing activities:

This year I was tandem parachuting four times, out of an airplane of 4000 meters height (first interview, lines 170-171). I love such challenges. I need something like this [parachuting, long distance motor cycling] in addition to my daily routine (first interview, lines 223-224).

Yesterday, we have played tennis. I must say that afterwards I need some relaxation (second interview, lines 330-331).

Occupational Balance-Questionnaire (OB-Quest)

The eight components of occupational balance identified in the qualitative analysis were used for the development of the questionnaire items, as shown in Table 2.

The first draft of the OB-Quest was piloted in 20 additional patients and healthy people. Based on their feedback some questions were reworded. The item activities intended to care for oneself and for others was deleted because patients complained that this question would not be relevant for those who did not care for others. The same applied to the example changed family circle in the item on the component adaptation of activities according to changed living conditions. Finally, seven items were formulated as presented in Table 2, second column.

Construct validity and internal consistency

The results of the overall fit, item and fit statistics referring to construct validity are shown in Table 3.

The following sets of items whose residual factors loaded most strongly were used for t-tests: variety of activities, adaptation of activities according to changed living conditions, impact of own health condition on activities, involvement in stressful and fewer stressful activities (negative loading), and challenging and relaxing activities, activities with acknowledgement by the individual and by the sociocultural context and rest and sleep (positive loading). The result of the t-test disproved the equivalence of test scores within the OB-Quest (t = 0.58, non-significant) and thus confounded our hypothesis on unidimensionality of the questionnaire. The item on the component rest and sleep showed DIF regarding the categories health condition and age. Furthermore, PSI was 0.51 and Cronbach’s α 0.38, revealing low internal consistency. Therefore, we decided to remove the items on the components challenging and relaxing activities and adaptation of activities according to changed living conditions.

After deleting these items (components challenging and relaxing activities and adaption of activities to changed living conditions) the t-test and Cronbach’s α changed. The new results of the t-test (t = 1.66, non-significant) were based on the use of the sets of items on the components involvement in stressful and fewer stressful activities and impact of health condition on activities (positive loading), activities with social acknowledgement, rest and sleep and variety of activities (negative loading). Furthermore, Cronbach’s α changed to 0.57 indicating an improved internal consistency.

Because the item on the component challenging and relaxing activities confounded the unidimensionality of the OB-Quest, we decided to split this item into two concepts: too much and too little demand. Consequently, the two new items read now as follows: "1. Do you generally find your activities in your everyday life under-demanding? 2. Do you generally find your activities in your everyday life over-demanding?" Additionally, the item on the component adaptation of activities to changed living conditions misfitted the model. Accordingly this item was split into two concepts also, as shown in Table 2 right column. Furthermore due to DIF (as described above), the item on the component rest and sleep was divided into two items: one on rest and the other on sleep. Additionally, several changes were made based on the feedback of patients, e.g. particular words were reformulated (difficult to understand and/or score; Table 2). The final OB-Quest is proposed as ten items addressing seven components. Subsequently, the revised German version was forward and back translated; the final English and German versions of the OB-Quest are presented in Tables 4 and5, respectively.

Discussion

This article describes the development of a new self-reported outcome instrument to assess occupational balance. Item development was based on an exploration of occupational balance in qualitative data and the involvement of patients with chronic autoimmune diseases and healthy people. Furthermore we validated and revised the OB-Quest based on quantitative data of patients with RA or SLE and healthy people.

The OB-Quest includes items which have not been covered so far by instruments used to assess occupational balance. Challenging and relaxing activities and adaptation of activities have already been identified as components of occupational balance[21, 38, 39]. Additionally, stress has also been related to occupational balance earlier[40]. However, the four components challenging and relaxing activities, involvement in stressful activities and fewer stressing activities, impact of health condition on activities, and adaptation of activities to changed living conditions have not been included in occupational balance instruments.

Different instruments have been used to assess single components of occupational balance, as identified in the current study. For example, the Short-Form 36-items Health Survey (SF-36)[41] assesses, besides other aspects, the impact of a health condition on activities of daily living (questions on health limiting daily activities). Another example is the Adolescent Stress Questionnaire which includes items on having enough time for activities others than school tasks[42]. Frequently used instruments, such as the Perceived Stress Questionnaire[43] or the Perceived Stress Scale[44] do not capture potential relations between stress and activities. However, a "composition" of the seven components, identified in our study within one instrument, has not been developed.

The results of this study indicate that occupational balance might be a multidimensional construct. Additionally, the results of the t-tests (0.58 and 1.66, respectively), indicated that the test scores vary within the OB-Quest items. Furthermore, the authors of previous studies came to the conclusion that occupational balance might be a multidimensional construct[45, 46]. Moreover, the two models of occupational balance which are based on empirical quantitative and qualitative data[10, 47] also challenge a unidimensional conceptualisation of occupational balance. The multidimensionality indicates that a total score of the instrument is not justified and thus requests the summary of several of the components into subscales, as this is the case in the SF-36[41]. Further research including components analysis is suggested to verify the various components of the OB-Quest.

The concept of "occupational imbalance" should be addressed in further research. Studies of occupational imbalance are scarce and findings are diverse[48]. For example, occupational imbalance, defined as interference among occupations, was negatively associated with subjective wellbeing[49] and life satisfaction[45]. However, this was not the case in another study on occupational imbalance[48]. Currently, it is unclear whether occupational balance and occupational imbalance represent opposite poles of one single dimension or two distinct concepts[45, 48].

The component activities intended to care for oneself and for others is important for the maintenance of occupational balance in people who have someone they care about. When assessing occupational balance in people who do care for others, the following question could be used: "Could you take sufficient care of yourself while caring for another (such as a family member, loved one, etc.)?" The inclusion of optional items was found to be justified in specific settings or circumstances[6]. However, due to the feedback of patients and healthy people, we decided to exclude this item of the OB-Quest.

Strengths and limitations

The development together with patients and healthy people, as well as the base on experiences of people with and without chronic autoimmune diseases strengthens the questionnaire’s construct validity[5, 13]. Additionally, this process followed common recommendations for the development of self-reported outcome instruments[5, 50] and resulted in the identification of new components of occupational balance. Cronbach’s α or the internal consistency of the questionnaire turned out to improve by the reduction of the items on the components challenging and relaxing activities and adaptation of activities according to changed living conditions. In the current study three of the four native speakers were without a health professional or patient perspective and conducted the forward and back translations of the different questionnaire versions. Another study could include patients of various diagnoses according to the International Classification of Diseases[19]. Moreover, a translation into different languages and an examination of the instrument’s psychometric properties in different countries all over the world, could allow an evaluation of its culture fairness. Additionally, a conceptual definition of occupational balance would be of great value and importance. We extracted components of occupational balance from qualitative data. However, we did not aim to provide a conceptual definition of occupational balance. The conceptualization of a concept requires a complex process of synthesizing the findings of several studies[51]. We suggest further studies on the conceptualization of occupational balance.

Conclusions

This questionnaire includes new items addressing components of occupational balance meaningful to patients and healthy people which have not been measured so far. The OB-Quest showed improved internal consistency after the reduction of two items, based on data obtained from patients with chronic autoimmune diseases and healthy people. The multidimensionality of the questionnaire indicates the need for a summary of several components into subscales.

Abbreviations

- α:

-

Alpha

- CD:

-

Crohn’s disease

- CDAI:

-

Clinical disease activity index

- Hba1c:

-

Glycosylated haemoglobin

- HBI:

-

Harvey Bradshaw Index

- OB-Quest:

-

Occupational balance-questionnaire

- PSI:

-

Person separation index

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- DIF:

-

Differential item functioning

- RA:

-

Rheumatoid arthritis

- SF-36:

-

Short-Form 36-items Health Survey

- SLE:

-

Systemic lupus erythematous

- SSc:

-

Systemic sclerosis

- T1D:

-

Diabetes mellitus type one

- SLEDAI:

-

Systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index

- RODNAN:

-

Rodnan skin score.

References

Johnston BC, Patrick DL, Busse JW, Schunemann HJ, Agarwal A, Guyatt GH: Patient-reported outcomes in meta-analyses–Part 1: assessing risk of bias and combining outcomes. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2013, 11: 109. 10.1186/1477-7525-11-109

Ahmed S, Berzon RA, Revicki DA, Lenderking WR, Moinpour CM, Basch E, Reeve BB, Wu AW, International Society for Quality of Life R: The use of patient-reported outcomes (PRO) within comparative effectiveness research: implications for clinical practice and health care policy. Med Care 2012, 50: 1060–1070. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318268aaff

Dinan MA, Compton KL, Dhillon JK, Hammill BG, Dewitt EM, Weinfurt KP, Schulman KA: Use of patient-reported outcomes in randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials. Med Care 2011, 49: 415–419.

Kirwan JR, Fries JF, Hewlett SE, Osborne RH, Newman S, Ciciriello S, van de Laar MA, Dures E, Minnock P, Heiberg T, Sanderson TC, Flurey CA, Leong AL, Montie P, Richards P: Patient perspective workshop: moving towards OMERACT guidelines for choosing or developing instruments to measure patient-reported outcomes. J Rheumatol 2011, 38: 1711–1715. 10.3899/jrheum.110391

Lasch KE, Marquis P, Vigneux M, Abetz L, Arnould B, Bayliss M, Crawford B, Rosa K: PRO development: rigorous qualitative research as the crucial foundation. Qual Life Res 2010, 19: 1087–1096. 10.1007/s11136-010-9677-6

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Knol DL, Stratford PW, Alonso J, Patrick DL, Bouter LM, de Vet HC: The COSMIN checklist for evaluating the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties: a clarification of its content. BMC Med Res Methodol 2010, 10: 22. 10.1186/1471-2288-10-22

Meyer A: The philosophy of occupation therapy. Reprinted from the archives of occupational therapy, volume 1, pp. 1–10, 1922. Am J Occup Ther 1977, 31: 639–642.

AOTA: American occupational therapy association. The role of occupational therapy in disaster preparedness, repsonse and recovery. Am J Occup Ther 2011, 65: S11-S25.

Backman CL: Occupational balance: exploring the relationships among daily occupations and their influence on well-being. Can J Occup Ther 2004, 71: 202–209. 10.1177/000841740407100404

Jonsson H, Persson D: Towards an experimental model of occupational balance: an alternative perspective on flow theory analysis. J Occup Sci 2006, 13: 62–73.

Stamm TA, Lovelock L, Stew G, Nell V, Smolen J, Machold K, Jonsson H, Sadlo G: I have a disease but I am not ill: a narrative study of occupational balance in people with rheumatoid arthritis. OTJR 2009, 29: 32–39.

Wilcock AA: The relationship between occupational balance and health: a pilot study. Occup Ther Int 1997, 4: 17–30. 10.1002/oti.45

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, Bouter LM, de Vet HC: The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 2010, 63: 737–745. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.006

Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D: Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol 1993, 46: 1417–1432. 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90142-N

Dür M, Sadlonova M, Haider S, Binder A, Stoffer M, Coenen M, Smolen J, Dejaco C, Kautzky-Willer A, Fialka-Moser V, Moser G, Stamm TA: Health determining concepts important to people with Crohn’s disease and their coverage by patient-reported outcomes of health and wellbeing. J Crohns Colitis 2014, 8: 45–55. 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.12.014

Stange EF, Travis SP, Vermeire S, Beglinger C, Kupcinkas L, Geboes K, Barakauskiene A, Villanacci V, Von HA, Warren BF, Gasche C, Tilg H, Schreiber SW, Scholmerich J, Reinisch W: European evidence based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: definitions and diagnosis. Gut 2006, 55(Suppl 1):i1–15.

Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, Healey LA, Kaplan SR, Liang MH, Luthra HS: The american rheumatism association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1988, 31: 315–324. 10.1002/art.1780310302

Manzi SM, Stark VE, Ramsey-Goldman R: Epidemiology and Classification of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. In Rheumatology. Volume 3 edition. Edited by: Hochberg MC, Silman A, Smolen JS, Weinblatt M, Weisman MH. Mosby: Edinburgh; 2003:1291–1296.

WHO: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10) Version for 2010. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010.

WHO: Definition And Diagnosis Of Diabetes Mellitus And Intermediate Hyperglycemia: Report Of A Who/Idf Consultation. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2006.

Stamm T, Wright J, Machold K, Sadlo G, Smolen J: Occupational balance of women with rheumatoid arthritis: a qualitative study. Musculoskeletal Care 2004, 2: 101–112. 10.1002/msc.62

Rosenthal G: Reconstruction of Life Stories. Principles of Selection in Generating Stories of Narrative Biographical Interviews. In The Narrative Study of Lives. Edited by: Josselson R, Lieblich A. Sage: Thousand Oaks; 1993:59–91.

SPSS: SPSS Statistics 17.00 for Windows. Chicago: SPSS Inc; 2008.

Rumm Laboratory PL: RUMM2030. Released in January 2010. License Re-structure from March 2012. Australia, Duncraig; 2012.

Tennant A, Pallant JF: Unidimensionality Matters! (A Tale of Two Smiths?). Rasch Measurement Transactions Volume 20 edition. 2006, 1048–1051. Archives of the Rasch Measurement SIG, AERA http://www.rasch.org/rmt/rmt201c.htm:

Andrich D: RASCH Models for Measurement. SAGE University Paper: Sara Miller McCune, SAGE Publications, Inc.; 1988.

Rumm Laboratory PL: Interpreting RUMM2030. PART I Dichotomus data. Australia, Duncraig; 2009.

Smith EV Jr: Detecting and evaluating the impact of multidimensionality using item fit statistics and principal component analysis of residuals. J Appl Meas 2002, 3: 205–231.

Rumm Laboratry PL: Extending the RUMM2030 Analysis. RUMM2030 Rasch Unidimensional Measurment Model. 8th edition. 2012.

Gibbons CJ, Mills RJ, Thornton EW, Ealing J, Mitchell JD, Shaw PJ, Talbot K, Tennant A, Young CA: Rasch analysis of the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) for use in motor neurone disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011, 9: 82. 10.1186/1477-7525-9-82

Bond TG, Fox CM: Applying the Rasch Model. Fundamental Measurement in the Human Science. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 2007.

Harvey RF, Bradshaw JM: A simple index of Crohn’s-disease activity. Lancet 1980, 1: 514.

Executive summary: standards of medical care in diabetes--2009 Diabetes Care 2009, 32 Suppl 1: S6–12.

Aletaha D, Nell VP, Stamm T, Uffmann M, Pflugbeil S, Machold K, Smolen JS: Acute phase reactants add little to composite disease activity indices for rheumatoid arthritis: validation of a clinical activity score. Arthritis Res Ther 2005, 7: 796–806. 10.1186/ar1740

Bombardier C, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Caron D, Chang CH: Derivation of the SLEDAI. A disease activity index for lupus patients. The committee on prognosis studies in SLE. Arthritis Rheum 1992, 35: 630–640. 10.1002/art.1780350606

Formiga F, Moga I, Pac M, Mitjavila F, Rivera A, Pujol R: High disease activity at baseline does not prevent a remission in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 1999, 38: 724–727. 10.1093/rheumatology/38.8.724

Seibold JR, McCloskey DA: Skin involvement as a relevant outcome measure in clinical trials of systemic sclerosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 1997, 9: 571–575. 10.1097/00002281-199711000-00014

Wagman P, Hakansson C, Bjorklund A: Occupational balance as used in occupational therapy: a concept analysis. Scand J Occup Ther 2012, 19: 322–327. 10.3109/11038128.2011.596219

Gibbs L, Klinger L: Rest is a meaningful occupation for women with hip and knee osteoarthritis. OTJR 2011, 31: 143–150.

Eriksson T, Westerberg Y, Jonsson H: Experiences of women with stress-related ill health in a therapeutic gardening program. Can J Occup Ther 2011, 78: 273–281.

Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD: The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992, 30: 473–483. 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002

De Vriendt T, Clays E, Moreno LA, Bergman P, Vicente-Rodriguez G, Nagy E, Dietrich S, Manios Y, De Henauw S, Group HS: Reliability and validity of the Adolescent Stress Questionnaire in a sample of European adolescents–the HELENA study. BMC Public Health 2011, 11: 717. 10.1186/1471-2458-11-717

Levenstein S, Prantera C, Varvo V, Scribano ML, Berto E, Luzi C, Andreoli A: Development of the perceived stress questionnaire: a new tool for psychosomatic research. J Psychosom Res 1993, 37: 19–32.

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R: A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 1983, 24: 385–396. 10.2307/2136404

Anaby DR, Backman CL, Jarus T: Measuring occupational balance: a theoretical exploration of two approaches. Can J Occup Ther 2010, 77: 280–288. 10.2182/cjot.2010.77.5.4

Forhan M, Backman C: Exploring occupational balance in adults with rheumatoid arthritis. OTJR 2010, 30: 133–141.

Jonsson H: A new direction in the conceptualization and categorization of occupation. J Occup Sci 2008, 15: 3–8.

Anaby D, Jarus T, Backman CL, Zumbo BD: The role of occupational characteristics and occupational imbalance in explaining well-being. Appl Res Qual Life 2010, 5: 81–104. 10.1007/s11482-010-9094-6

Riediger M, Freund AM: Interference and facilitation among personal goals: differential associations with subjective well-being and persistent goal pursuit. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2004, 30: 1511–1523. 10.1177/0146167204271184

Kirwan JR, Fries JF, Hewlett S, Osborne RH: Patient perspective: choosing or developing instruments. J Rheumatol 2011, 38: 1716–1719. 10.3899/jrheum.110390

Jaccard J, Jacoby J: Theory Construction and Model-Building Skills (Methodology in the Social Sciences). London: Guilford Press; 2009.

Acknowledgements

Partly funded by a restricted grant of the Austrian Science Fund (FWF): [P21912-B09]. We thank people for their participation and the important contributions for this study. We thank Linda Lovelock for her support with the item development, and Philip Graf, Vallerie Nell-Duxneuner and Andrea Jordan for translating the questionnaire.

Data sharing statement

The data from the current study will be made available upon request to the corresponding author (TAS), according to the guidelines from the funding agency and the ethical approval of the ethics committee of the Medical University of Vienna, Austria.

Partly funded by a restricted grant of the Austrian Science Fund (FWF): [P21912-B09].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

There are no declared competing interest of the authors.

Authors’ contributions

MD and TS were involved into conception and design, the acquisition of data, the analysis and interpretation of data, wrote the draft manuscript, and gave final approval of the manuscript. GS contributed to the conception and design of the study, assisted the data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, and the draft version, and finally gave advice on editing of manuscript. AK-W, VF-M, CD, and JS, gave substantial contributions to conception and design, supported the acquisition of the data, have been involved in revising the draft manuscript critically, and finally approved the manuscript considered for publication. BP was involved into conception, design of the study, and item development, supported the analysis and interpretation of the data, contributed substantially to the draft manuscript and approved the final version. AB was involved into the conception and design, item development, the acquisition and the interpretation of the data, the writing of the draft manuscript and gave final approval of the manuscript. MAS was involved into the acquisition and the interpretation of the data, the writing of the draft manuscript and gave final approval of the manuscript. The authors have taken an active part in the study and take responsibility for its contents. The FWF had no influence on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Dür, M., Steiner, G., Fialka-Moser, V. et al. Development of a new occupational balance-questionnaire: incorporating the perspectives of patients and healthy people in the design of a self-reported occupational balance outcome instrument. Health Qual Life Outcomes 12, 45 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-12-45

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-12-45