Abstract

Background

The SF-36 physical functioning scale (PF-10) and the Health Assessment Questionnaire disability index (HAQ-DI) are the most frequently used instruments for measuring self-reported physical function in rheumatoid arthritis (RA). The objective of this study was to develop a crosswalk between scores on the PF-10 and HAQ-DI in RA.

Methods

Item response theory (IRT) methods were used to co-calibrate both scales using data from 1791 RA patients. The appropriateness of a Rasch-based crosswalk was evaluated by comparing it with crosswalks based on a two-parameter and a multi-dimensional IRT model. The accuracy of the final crosswalk was cross-validated using baseline (n = 532) and 6-month follow-up (n = 276) data from an independent cohort of early RA patients.

Results

The PF-10 and HAQ-DI adequately fit a unidimensional Rasch model. Both scales measured a wide range of functioning, although the HAQ-DI tended to better target lower levels of functioning. The Rasch-based crosswalk performed similarly to crosswalks based on the two-parameter and multidimensional IRT models. Agreement between predicted and observed scale scores in the cross-validation sample was acceptable for group-level comparisons. The longitudinal validity in discriminating between disease response states was similar between observed and predicted scores.

Conclusion

The crosswalk developed in this study allows for converting scores from one scale to the other and can be used for group-level analyses in patients with RA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The SF-36 physical functioning scale (PF-10) [1, 2] and the Health Assessment Questionnaire disability index (HAQ-DI) [3, 4] are well-established instruments for measuring self-reported physical functioning. The SF-36 and the HAQ-DI were originally developed as generic measures to allow comparisons across populations [2, 5]. but both instruments have also been thoroughly examined for use in several specific conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [6].

Since the inclusion of patient-reported physical disability into core sets of outcomes for clinical trials and observational studies in RA [7, 8], an increasing number of RA studies now assess and report physical functioning. Although variation in the choice of instrument exists, the HAQ-DI and PF-10 are among the most frequently used [9, 10]. Both measures, however, differ considerably in their content, number of items, and scoring procedures, making it difficult to directly compare results obtained with the two scales. One way to overcome this problem is to link scores from the HAQ-DI and PF-10 [11]. This would allow the development of a concordance table, or crosswalk, to convert scores from one instrument to another and enable comparison of data from studies that used either one of the instruments.

Several methods are available for linking scale scores that vary in design, statistical techniques, and the degree to which exchangeability can be achieved [11, 12]. Item response theory (IRT) offers a flexible and powerful framework for score linking by its inherent ability to calibrate different items of the same concept on a common underlying metric [13–16]. Several examples of how to use IRT modeling to develop crosswalks between different instruments intended to measure the same health domain have been reported [17–20]. IRT, however, makes certain assumptions about the nature of the data, in particular with respect to dimensionality. A variety of models are available, which differ in their restrictiveness with respect to the assumptions made and the number of parameters used to describe items [21]. Consequently, the type of linking and the accuracy of the resulting crosswalk may depend in part on the specific IRT model used.

The most basic form of IRT-based linking is possible when the responses on the two instruments follow the same Rasch model; that is, if it can be shown that they pertain to the same unidimensional latent trait and that all items are equally discriminating. In the Rasch model, the observed sum score is a sufficient statistic for the latent trait estimate [22]. If the Rasch model fits, linking boils down to estimating the trait level associated with an observed score on instrument A and then finding the observed score on instrument B associated with that trait level. In this approach, the statistical equating error is merely a function of the reliability of the two instruments, that is, the reliability with which trait levels can be estimated using either of the two instruments.

If the Rasch model does not fit, a more general model can be used such as a two-parameter IRT model that includes a discrimination parameter for differentially weighting the association of items with the latent variable. Although this extension may improve model fit, linking is less straightforward as the observed sum score is no longer a sufficient statistic for the trait level and, conditional on an observed sum score, estimates of trait levels vary to some degree. In this approach, an observed score on instrument A is associated with an expected trait level and from this expectation an expected observed score on instrument B is estimated. As such, the resulting crosswalk contains a second source of statistical error, attributable to the variation of the trait level given observed sum scores. This error, in turn, is a function of the magnitude of the discrimination indices, that is, the strength of the association of the items with the latent variable.

The linking approach can be further generalized by assuming that the two instruments measure two different, yet correlated latent variables. This situation can be modeled by a two-dimensional IRT model, where the responses on one instrument pertain to one latent variable, and the aggregation of the two latent variables has a two-dimensional normal distribution. Again, the observed sum score on instrument B is estimated from the observed score on instrument A via the IRT model. Added to the two sources of statistical error already identified, is an error associated with the magnitude of the correlation between the two latent variables, that is, the strength of the association between the two assumed latent scales.

To date, no studies have attempted to link PF-10 and HAQ-DI scores. Moreover, although many studies have reported high correlations between the instruments, the degree and consequences of the multidimensionality that would result from combining the scales are unclear. Some previous studies have suggested that the PF-10 and HAQ-DI, or a selection of its items used in the modified HAQ, do essentially measure the same concept [23, 24]. However, studies that examined whether items from both scales could actually be calibrated on a common IRT metric did not unequivocally support either a unidimensional or multidimensional latent structure [25, 26]. Moreover, these studies did not compare the performance of different IRT models to further examine the impact of multidimensionality.

This study presents the development and evaluation of a crosswalk between the PF-10 and the HAQ-DI in a large and clinically diverse sample of patients with RA who completed both instruments. The appropriateness of different IRT models is taken into account by comparing the calibrations and performance of a crosswalk based on a one-parameter Rasch model with those of its two-parameter and multidimensional extensions. The accuracy of the final crosswalk is cross-validated in an independent sample of patients with early RA participating in a treatment-to-target study.

Methods

Study populations

Two independent datasets were used for this study. The first dataset was used for IRT calibrations and development and comparison of the crosswalks between the PF-10 and the HAQ-DI. Accuracy and validity of the final crosswalk were tested in the second dataset.

Calibration sample

This dataset was derived from the Dutch Rheumatoid Arthritis Monitoring (DREAM) registry [27]. The DREAM registry is an observational multicenter cohort study that monitors the course of RA patients undergoing different treatment regimens in the Netherlands. Clinical, laboratory, and patient-reported outcomes are routinely collected and stored. Patient-reported outcomes are generally completed online. Within the different DREAM cohorts, 1791 unique patients simultaneously completed the SF-36 and HAQ-DI at least once between 2003 and 2012. For every patient, the first available simultaneous assessment was selected for analysis.

Cross-validation sample

The second, independent dataset included data from patients participating in the DREAM remission induction cohort [28]. The remission induction cohort consists of patients with early RA participating in a treat-to-target strategy aimed at achieving fast remission. The strategy has been shown to be highly effective, with the largest improvement in disease activity observed in the first 6 months of treatment [28]. Data from 532 patients who completed the HAQ-DI and SF-36 at baseline were used to cross-validate the accuracy of the Rasch-based crosswalk. To study the longitudinal performance of the crosswalk, available data of 276 patients who also completed the HAQ and PF-10 after six months were used.

Measures

SF-36 physical functioning scale (PF-10)

The PF-10 is one of the eight scales of the SF-36 Health Survey and consists of 10 items measuring perceived current limitations in a variety of physical activities on a 3-point response scale from 1 (yes, limited a lot) to 3 (no, not limited at all). Where there are no missing data, observed PF-10 scores can have 21 possible values, with higher scores indicating more favorable levels of physical functioning. Using traditional scoring, scores on the PF-10 items are summed and linearly transformed to range between 0 and 100. Additionally, the summed scores can be standardized using norm-based scoring based on a mean score of 50 and a standard deviation of 10 in the 1998 US general population [29]. Previous Rasch modeling of the PF-10 indicated that the items form a unidimensional, hierarchical continuum with stable item difficulty estimates across diverse patient groups [24, 30].

Health Assessment Questionnaire disability index (HAQ-DI)

The HAQ-DI contains 20 items measuring physical disabilities over the past week in eight categories of daily living: dressing and grooming, rising, eating, walking, hygiene, reach, grip, and activities. Each item is scored on a 4-point rating scale from 0 (without any difficulty) to 3 (unable to do). Additionally, the HAQ-DI contains four sections on the use of aids and devices or need for help from another person for performing activities in any of the eight categories. Two scoring methods can be used to calculate total HAQ-DI scores [31]. The standard disability index (SDI) adjusts category scores upwards for the use of aids or devices or help from others. The alternative disability index (ADI) does not take the use of aids and devices into account. For both scoring methods, the total disability score (HAQ-DI) is calculated by determining the highest score in each of the eight categories and then averaging the category scores. As a result, observed scores on the HAQ-DI can take on 25 possible values between 0 and 3, with higher values indicating more disability. Recent Rasch analyses have shown that the categories of the HAQ-DI constitute a unidimensional scale [24, 32].

Statistical analyses

IRT modeling

The maximum likelihood estimation procedure was utilized to estimate the structural model parameters and the latent disability levels of patients were estimated using the expected a posteriori (EAP) method throughout all IRT analyses. Model fit of all estimated models was assessed using Lagrange multiplier (LM) item fit statistics specifically targeted at polytomously scored items [33, 34]. Absolute differences (effect sizes; ES) between expected and observed item scores for high, average and low scoring individuals were computed. In accordance with previous research, model fit was considered acceptable if all ES statistics were <0.10 [35, 36]. As the ES is weighted by the number of response categories, this cutoff reflects differences between observed and expected score frequencies of 2.5% for the HAQ-DI and 3.33% for the PF-10, respectively. All IRT analyses were performed with the MIRT software package [37].

Development of the crosswalk

Initial IRT analysis and cross-calibration of the PF-10 and HAQ-DI were performed in the calibration sample. To achieve consistent response patterns, PF-10 scores were reversed (so a lower score indicates better function) preceding analysis. Item parameters for the Rasch-based crosswalk were obtained using the polytomous partial credit model (PCM) [38]. First, the 10 PF-10 items and the eight HAQ-DI category scores were jointly calibrated in the same model. After the structural model parameters were estimated, questionnaire-specific scoring runs on the HAQ-DI and PF-10 items only were performed to estimate EAP scores associated with all possible total score levels and to create scoring tables mapping this relation. In these runs the item parameters of the HAQ-DI and PF-10 items, respectively, were fixed to the values obtained in the initial co-calibration. Subsequently, each possible total score was linked to the total score on the other instrument for which the absolute distance between EAP scores on the latent scale was the smallest. The total procedure was separately performed for both the HAQ-SDI based category scores and the HAQ-ADI based category scores.

Next, the validity and appropriateness of the Rasch-based crosswalk was evaluated by determining its precision to correctly predict HAQ-DI scores from PF-10 scores and vice versa and comparing the results to the precision of two additional crosswalks that were developed using the two-parameter and multidimensional extensions of the PCM. Using the same general approach as outlined above, we first re-estimated the model parameters using the generalized partial credit model (GPCM). The GPCM model is a two-parameter IRT model for polytomous data which includes a discrimination parameter that accounts for the different reliability of individual items with respect to measuring the underlying latent trait. As such, the PCM is nested within the GPCM. Finally, a between-item, multidimensional GPCM model was estimated. Again, the GPCM model is nested within the multidimensional GPCM model. In this model, all items were specified to load on their own questionnaire-specific dimension, and the relation between the dimensions was modeled by their correlation. Because in this model the two dimension-specific EAP scores are estimated concurrently, no separate scoring runs needed to be performed for the HAQ-DI and PF-10 to obtain questionnaire-specific EAP estimates associated with all possible total scores.

Agreement between patients’ observed and predicted scores on the PF-10 and HAQ-DI was assessed by computing intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) with 95% confidence intervals using two-way mixed effects models with absolute agreement for single measurements (type A,1) [39]. ICCs were considered adequate for group level comparisons when ≥0.70 [40].

Cross-validation of the results

The final step of the analyses was to apply the crosswalk in the cross-validation sample and to evaluate the agreement between observed and predicted HAQ-DI and PF-10 scores. Agreement between patients’ observed and crosswalked scores on the PF-10 and HAQ-DI at baseline (n = 532) was again assessed by computing ICCs (type A,1). Additionally, Bland-Altman plots of the difference against the mean of predicted and observed scores were constructed [41, 42]. As a final test of the validity of the crosswalk, observed and predicted change scores and total effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated for patients who completed both measures at baseline and 6-month follow-up (n = 276). The relative efficiency of the change scores to discriminate between responder status was analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests [43, 44]. The 28-joint Disease Activity Score (DAS28), a pooled index that includes a tender joint count, a swollen joint count, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and the patient’s global assessment of general health, was used as the external criterion for determining response to treatment [45]. Patients were classified as good responders at 6 months when the DAS28 score had improved at least 1.2 points and the final score was ≤3.2 [46]. For purposes of comparing results, relative validity (RV) coefficients with 95% bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrap confidence intervals [44, 47] for the predicted scores in relation to the actual observed scores were computed.

Results

Patient characteristics

The calibration and cross-validation samples were comparable with respect to demographic characteristics (Table 1). However, baseline physical functioning levels were substantially better in the cross-validation sample, as measured with both the HAQ-DI and the PF-10. Patients in the cross-validation sample had moderately active disease on average at baseline according to the DAS28.

Development of the Rasch-based crosswalk

Total scores on the PF-10 and HAQ-DI were strongly correlated (r = −0.75 for both the HAQ-SDI and HAQ-ADI). Both the Rasch-based co-calibration of the HAQ-SDI and PF-10 items and the co-calibration of HAQ-ADI and PF-10 items resulted in a model that adequately fitted the data according to the LM tests, with all accompanying ESs <0.10 (Additional file 1: Table S1 and S2).

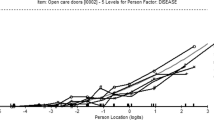

Figure 1 presents the test information functions which describe the local reliability of the PF-10 and HAQ-SDI. Both scales measured an approximately equally wide range of physical functioning with high precision. Overall, the PF-10 was slightly more precise at better levels of physical functioning (i.e., lower theta values), whereas the HAQ-SDI tended to provide more information at worse levels of functioning.

Table 2 presents the resulting Rasch-based crosswalks between the PF-10 and HAQ-DI. Separate cross-walks are presented for the standard and alternative scoring rule of the HAQ-DI. As would be expected, predicted HAQ-ADI scores were generally lower than predicted HAQ-SDI scores, for a given level of the PF-10. This effect was strongest in the range of HAQ-DI scores from 1 to 2, where for the same observed PF-10 total scores, the estimated HAQ-SDI scores were consistently 0.25 points (i.e. two score levels) higher than the HAQ-ADI scores. Observed HAQ-ADI and HAQ-SDI scores ≥2.75 were linked to locations on the EAP theta scale that were below the lowest possible score for the PF-10 scale. Conversely, observed PF-10 scores of 95 and 100 were linked to EAP scores that reflect levels of function that are not represented in the HAQ-DI. They were therefore linked to the value zero in the crosswalks.

Comparative performance of the Rasch-based crosswalk

Model fit of the co-calibrations based on the two-parameter GPCM and the multi-dimensional IRT model improved marginally as compared with the Rasch model (Additional file 1: Table S3–S6). For both the GPCM and the multi-dimensional model, ESs were also <0.10 and generally slightly smaller than those observed in the Rasch model. The correlation between the latent dimensions in the multidimensional models was 0.73. The crosswalks based on the GPCM and multi-dimensional IRT model were almost identical to the Rasch-based crosswalk. Correlations between predicted scores based on the different crosswalks were very high (r’s >0.988). Moreover, the crosswalks based on the two-parameter and multidimensional models did not perform substantially better in terms of agreement between observed and predicted total scores on the PF-10 and HAQ-DI (Table 3). Considering that the Rasch-based calibration fitted the data well according to pre-specified criteria and that the agreement between observed and predicted scale scores did not improve much in the more general models, it was concluded that the Rasch-based crosswalk was adequate for converting total scale scores.

Cross-validation of the results

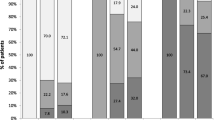

The agreement between observed scores and scores predicted from the Rasch-based crosswalk was high in the cross-validation sample. The ICCs (95% CI) between predicted and actual scores were 0.78 (0.74 to 0.81) for the HAQ-SDI, 0.77 (0.72 to 0.80) for the HAQ-ADI and 0.79 (0.75 to 0.82) for the PF-10, indicating adequate agreement for group-level comparisons. Additionally, group mean differences on both scales were small in magnitude (Table 4). Intra-individual differences were similarly distributed above and below the mean and not related to the magnitude of the measurement (Figure 2). However, the limits of agreement were wide for both scales and showed substantial discrepancies in agreement within individual patients.

Bland-Altman plots for agreement between observed and predicted HAQ-SDI (top left), HAQ-ADI (top right) and PF-10 scores (bottom left: predicted from HAQ-SDI, bottom right: predicted from HAQ-ADI). The y-axes represent the difference between observed and predicted scores. The x-axes represent the mean of observed and predicted scores. The horizontal solid lines represent the mean difference between both scores. The dashed lines represent the 95% limits of agreement.

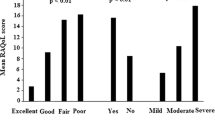

With respect to the observed 6-month change scores in the total cross-validation sample (Table 5), standardized improvements were largest for the HAQ-DI (ES = 0.55), closely followed by the HAQ-SDI (ES = 0.49) and the PF-10 (ES = 0.40). In terms of differentiating between levels of longitudinal treatment response, the HAQ-ADI was slightly more efficient than the HAQ-SDI and PF-10. Relative validity coefficients of the predicted scores were close to, and not significantly different from, those of the actual observed scores for all three scales.

Discussion

This study used IRT methods to analyze and link two widely used scales for measuring physical functioning, the PF-10 and the HAQ-DI. Results showed that it was possible to develop a straightforward Rasch-based crosswalk between both scales that can be used to estimate scores on one scale from scores on the other in patients with RA. The Rasch-based crosswalk performed similarly to crosswalks based on its two-parameter and multidimensional extensions. The application of the crosswalk in an independent sample of patients with early RA indicated that the crosswalk can be validly used for group-level analyses in RA populations.

Test linking or test equating has long been the focus of research in educational and psychological settings [12, 48]. More recently, the desire for standardization has also found its way to health outcomes measurement. As in educational testing, linking of existing health outcome instruments could enhance meaningful comparison and interpretation of results across studies and populations. With the rise of IRT in health outcomes assessment, new techniques have become available to achieve this objective. This is reflected in an increasing number of studies that have linked different patient-reported measures using IRT-based methods, including several measures of physical functioning [15, 17, 19, 49–55]. These crosswalks allow researchers to compare their results with studies and populations where another instrument was used and may improve the common understanding of the specific underlying construct. Moreover, they may be particularly useful for compilation of findings in meta-analytic studies or longitudinal studies focusing on measuring effects or changes [56]. A such, crosswalks are an important step in achieving better interpretation and comparability of patient-reported outcomes measures across different studies [57]. A next possible step in the standardization and promotion of a common measurement system of patient-reported outcomes, is the development of large IRT-calibrated item banks such as those developed by the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) initiative [58]. These item banks can be used to build flexible short forms and computer adaptive tests for different populations or clinical conditions, while scores on these measures remain directly comparable. Recent studies have already shown the promise of this approach in RA [59].

The current study used an elaborate approach for cross-calibrating the HAQ-DI with the PF-10 and developing and evaluating the crosswalk, especially in its choice for comparing different IRT models. IRT linking studies usually do not explain or justify their use of a specific IRT model, such as the Rasch model or more general models. When using IRT analysis, however, the differences in model assumptions should be taken into account and the final model choice should be motivated by considering aspects such as the unidimensionality and the discrimination equality of the items [60]. Moreover, it should be shown to what degree the used model holds. In the case of using IRT for linking total scale scores, the specific model used may have consequences for the robustness and accuracy of the resulting crosswalk. This article presents a straightforward and practical IRT-based approach of linking total scale scores that includes comparing the fit and performance of different nested IRT models. This approach can be used for future studies aimed at linking different instruments intended to measure the same construct. An important feature of the approach is that it can be used for calibrating scales with polytomous items, which is the case with most patient-reported outcomes. Contrary to the Rasch model, tests of model fit for more complex models for polytomous items which are based on test statistics with known asymptotic distributions are rare. Therefore, the presented approach uses the LM test throughout all fit analyses [34].

Additionally, most IRT linking studies to date have not tested the performance of the crosswalks in clinically different, independent samples. To our knowledge, this study is the first to cross-validate a crosswalk of physical functioning scales in a clinical setting. One recent study did validate a crosswalk for fatigue using data from a subsequent time point, but acknowledged that using an independent sample would have been preferable [56]. With the objective in mind of creating a robust crosswalk in this study, its development was performed in a large and diverse sample of RA patients with a wide range of physical functioning levels. Subsequently, the performance of the crosswalk was examined in a specific sample of patients with early disease.

The results of the IRT calibrations suggested that the PF-10 and the HAQ-DI essentially measure the same unidimensional construct and could be adequately fitted to the same Rasch model. The finding that the simple Rasch model performed similarly to more general models in calibrating both scales may have several theoretical and practical advantages [61–63]. An advantage in the case of total score linking is that each observed total instrument score is associated with only one latent trait (theta) score, making the resulting crosswalk more straightforward and robust against statistical error.

The evaluation of the measurement precision of the PF-10 and HAQ-DI under the Rasch model showed that the HAQ-DI and the PF-10 both measured a wide range of physical functioning in patients with RA. However, the HAQ-DI provided its optimal measurement precision at worse levels of physical function, whereas the PF-10 had better precision at somewhat better levels on the physical function continuum. This corresponds with previously reported ceiling effects of the HAQ-DI in less disabled populations [24, 64–66] and floor effects of the PF-10 in more disabled populations [67–70]. These effects were also apparent in the final crosswalk, where the HAQ-DI was better able to distinguish different scores at the lower end of the physical functioning spectrum and the PF-10 could better distinguish scores at the upper end. This supports previous findings that combining items from the HAQ-DI and PF-10 can reduce floor and ceiling effects and results in a scale with increased measurement precision and sensitivity to change across a wider range of physical functioning [25].

In the current study, separate crosswalks were developed for so-called standard (SDI) and alternative disability index (ADI) scoring of the HAQ-DI [5]. In the standard scoring method, the score on a category of daily living is corrected upwards when a respondent indicates the use of help from others or a device for performing one of the items in this category. Consequently, SDI scores are generally higher than ADI scores. Although the average difference between both scoring methods has been reported to be very small in general populations or populations with mild disability [71], SDI scores have been shown to be up to 0.15 to 0.26 points higher than ADI scores in samples with increasing disability levels [65, 72–74]. In the current study, this resulted in higher predicted scores for the SDI than for the ADI, especially for patients with worse levels of functioning. Therefore, care must be taken in using the correct crosswalk when converting PF-10 and HAQ-DI scores. Unfortunately, published studies do not always clearly specify which method was used to compute the HAQ-DI scores [75, 76]. If necessary and possible, researchers should therefore re-analyze the original data to compute the correct HAQ-DI scores.

Additionally, we presented the cross-walk for both the original and the norm-based scoring method of the PF-10. The original 0–100 scoring has been most frequently used in the literature to date. Since the introduction of version 2 of the SF-36, however, all eight scales can also be linearly transformed to T-scores based on normative data from the US general population [29]. This norm-based scoring method has become increasingly popular as it allows for easier interpretation of differences across scales and populations.

The two RA samples used to develop and evaluate the crosswalk in this study correspond with the two major populations of interest in current clinical studies in RA. The sample used to cross-calibrate the PF-10 and HAQ-DI represents the general and clinically diverse RA population seen in the everyday clinical practice and the distribution of age, sex, and functional disability scores in this sample corresponds closely with the characteristics reported in other large observational studies [77–79]. The cross-validation was performed in a sample of RA patients with a maximum symptom duration of one year. This population is gaining increasing research interest, mainly due to the development of effective biological treatments and the implementation of new treatment guidelines [80, 81]. The finding that the crosswalk also performed well in this very specific sample, provides further support for its wide applicability in RA research.

It should be noted, however, that RA is characterized by very specific disease mechanisms and physical manifestations, such as a high frequency of dexterity problems. Consequently, the IRT item parameters of the HAQ-DI and PF-10 may vary between conditions and populations as was previously shown for the HAQ-DI across different rheumatic diseases [35]. Therefore, future studies should cross-validate the crosswalk in both general and other disease-specific populations.

Further, the crosswalk is not suitable for use at the individual patient level. Although ICCs between observed and predicted scores were adequate for group-level analyses, they were not sufficiently high to warrant individual level analyses. This was confirmed by the Bland-Altman analyses, which showed that observed and predicted scores were characterized by high intra-individual variation. Therefore, cross-walked scores are not equivalent at an individual level and cannot be used interchangeably.

Conclusions

In sum, the crosswalk developed in this study enables the conversion of PF-10 scores into HAQ-DI scores and vice versa in patients with RA. Using the crosswalk will allow for group-level comparisons of data from studies that used either of the scales and can facilitate more meaningful interpretation and comparison of results. Future studies should examine the robustness of the crosswalk in other populations.

Abbreviations

- ADI:

-

Alternative disability index

- DAS28:

-

28-joint disease activity score

- DREAM:

-

Dutch rheumatoid arthritis monitoring

- EAP:

-

Expected a posteriori

- ES:

-

Effect size

- GPCM:

-

Generalized partial credit model

- HAQ-DI:

-

Health assessment questionnaire disability index

- ICC:

-

Intraclass correlation coefficient

- IRT:

-

Item response theory

- LM:

-

Lagrange multiplier

- PCM:

-

Partial credit model

- PF-10:

-

10-item physical functioning scale

- RA:

-

Rheumatoid arthritis

- RV:

-

Relative validity

- SDI:

-

Standard disability index

- SF-36:

-

Short-form 36-item health survey.

References

Stewart AL, Kamberg CJ: Physical functioning measures. In Measuring functioning and well-being. Edited by: Stewart AL, Ware JEJr. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1992:86–101.

Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD: The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992, 30: 473–483. 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002

Fries JF, Spitz P, Kraines RG, Holman HR: Measurement of patient outcome in arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1980, 23: 137–145. 10.1002/art.1780230202

Fries JF, Spitz PW, Young DY: The dimensions of health outcomes: the Health Assessment Questionnaire, disability and pain scales. J Rheumatol 1982, 9: 789–793.

Bruce B, Fries JF: The Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ). Clin Exp Rheumatol 2005, 23: S14-S18.

Oude Voshaar MA, ten Klooster PM, Taal E, van de Laar MA: Measurement properties of physical function scales validated for use in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of the literature. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011, 9: 99. 10.1186/1477-7525-9-99

Boers M, Tugwell P, Felson DT, van Riel PL, Kirwan JR, Edmonds JP, Smolen JS, Khaltaev N, Muirden KD: World health organization and international league of associations for rheumatology core endpoints for symptom modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. J Rheumatol 1994, 21: 86–89.

Wolfe F, Lassere M, van der Heijde D, Stucki G, Suarez-Almazor M, Pincus T, Eberhardt K, Kvien TK, Symmons D, Silman A, et al.: Preliminary core set of domains and reporting requirements for longitudinal observational studies in rheumatology. J Rheumatol 1999, 26: 484–489.

Kalyoncu U, Dougados M, Daures JP, Gossec L: Reporting of patient-reported outcomes in recent trials in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review. Ann Rheum Dis 2009, 68: 183–190. 10.1136/ard.2007.084848

Kirkham JJ, Boers M, Tugwell P, Clarke M, Williamson PR: Outcome measures in rheumatoid arthritis randomised trials over the last 50 years. Trials 2013, 14: 324. 10.1186/1745-6215-14-324

Dorans NJ: Linking scores from multiple health outcome instruments. Qual Life Res 2007, 16: 85–94. 10.1007/s11136-006-9155-3

Lim RL: Linking results of distinct assessments. Appl Meas Educ 1993, 6: 83–102. 10.1207/s15324818ame0601_5

Chang CH, Reeve BB: Item response theory and its applications to patient-reported outcomes measurement. Eval Health Prof 2005, 28: 264–282. 10.1177/0163278705278275

McHorney CA: Generic health measurement: past accomplishments and a measurement paradigm for the 21st century. Ann Intern Med 1997, 127: 743–750. 10.7326/0003-4819-127-8_Part_2-199710151-00061

McHorney CA, Cohen AS: Equating health status measures with item response theory: illustrations with functional status items. Med Care 2000, 38: II43-II59.

Reise SP, Waller NG: Item response theory and clinical measurement. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2009, 5: 27–48. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153553

Fisher WP Jr, Eubanks RL, Marier RL: Equating the MOS SF36 and the LSU HSI physical functioning scales. J Outcome Meas 1997, 1: 329–362.

Orlando M, Sherbourne CD, Thissen D: Summed-score linking using item response theory: application to depression measurement. Psychol Assess 2000, 12: 354–359.

Carmody TJ, Rush AJ, Bernstein I, Warden D, Brannan S, Burnham D, Woo A, Trivedi MH: The Montgomery Asberg and the Hamilton ratings of depression: a comparison of measures. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2006, 16: 601–611. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2006.04.008

Fischer HF, Tritt K, Klapp BF, Fliege H: How to compare scores from different depression scales: equating the patient health questionnaire (PHQ) and the ICD-10-symptom rating (ISR) using item response theory. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2011, 20: 203–214. 10.1002/mpr.350

Hambleton RK, Swaminathan H, Rogers HJ: Fundamentals of item response theory. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991.

Andersen EB: Sufficient statistics and latent trait models. Psychometrika 1977, 42: 69–81. 10.1007/BF02293746

Escalante A, Del RI, Cornell JE: Latent variable approach to the measurement of physical disability in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2004, 51: 399–407. 10.1002/art.20404

Taylor WJ, McPherson KM: Using Rasch analysis to compare the psychometric properties of the Short Form 36 physical function score and the health assessment questionnaire disability index in patients with psoriatic arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2007, 57: 723–729. 10.1002/art.22770

Martin M, Kosinski M, Bjorner JB, Ware JE Jr, Maclean R, Li T: Item response theory methods can improve the measurement of physical function by combining the modified health assessment questionnaire and the SF-36 physical function scale. Qual Life Res 2007, 16: 647–660. 10.1007/s11136-007-9193-5

Rose M, Bjorner JB, Becker J, Fries JF, Ware JE: Evaluation of a preliminary physical function item bank supported the expected advantages of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). J Clin Epidemiol 2008, 61: 17–33. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.06.025

Kievit W, Fransen J, Oerlemans AJ, Kuper HH, van de Laar MA, de Rooij DR, De Gendt CM, Ronday KH, Jansen TL, van Oijen PC, et al.: The efficacy of anti-TNF in rheumatoid arthritis, a comparison between randomized controlled trials and clinical practice. Ann Rheum Dis 2007, 66: 1473–1478. 10.1136/ard.2007.072447

Vermeer M, Kuper HH, Hoekstra M, Haagsma CJ, Posthumus MD, Brus HL, van Riel PL, van de Laar MA: Implementation of a treat-to-target strategy in very early rheumatoid arthritis: results of the Dutch rheumatoid arthritis monitoring remission induction cohort study. Arthritis Rheum 2011, 63: 2865–2872. 10.1002/art.30494

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Dewey JE: How to score version 2 of the SF-36 health survey (standard & acute forms). QualityMetric Inc: Lincoln, RI; 2000.

Haley SM, McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr: Evaluation of the MOS SF-36 physical functioning scale (PF-10): I. Unidimensionality and reproducibility of the Rasch item scale. J Clin Epidemiol 1994, 47: 671–684. 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90215-1

Fries JF: The Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) and the Improved HAQ. Stanford: Stanford University School of Medicine, Division of Immunology & Rheumatology; 2009. Available at: http://aramis.stanford.edu/haq.html

ten Klooster PM, Taal E, van de Laar MA: Rasch analysis of the Dutch health assessment questionnaire disability index and the health assessment questionnaire II in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2008, 59: 1721–1728. 10.1002/art.24065

Glas CAW: Modification indices for the 2-PL and the nominal response model. Psychometrika 1999, 64: 273–294. 10.1007/BF02294296

Glas CAW: Testing fit to IRT models for polytomously scored items. In Handbook of polytomous item response theory models. Edited by: Nering ML, Ostini R. New York, NY: Routledge; 2010:185–210.

van Groen MM, ten Klooster PM, Taal E, van de Laar MA, Glas CA: Application of the health assessment questionnaire disability index to various rheumatic diseases. Qual Life Res 2010, 19: 1255–1263. 10.1007/s11136-010-9690-9

Oude Voshaar MA, Glas CA, ten Klooster PM, Taal E, Wolfe F, van de Laar MA: Cross-cultural measurement equivalence of the health assessment questionnaire-II. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012, 65: 1000–1004.

Glas CA: Preliminary manual of the software program Multidimensional Item Response Theory (MIRT). Enschede, The Netherlands: University of Twente; 2010. Available at: http://www.utwente.nl/gw/omd/en/employees/employees/glas.doc/

Masters GN, Wright BD: The partial credit model. In Handbook of modern item response theory. Edited by: van der Linden WJ, Hambleton RK. New York: Springer; 1997:101–122.

McGraw KO, Wong SP: Forming inferences about some intraclass correlation coefficients. Psychol Methods 1996, 1: 30–46.

Lohr KN: Assessing health status and quality-of-life instruments: attributes and review criteria. Qual Life Res 2002, 11: 193–205. 10.1023/A:1015291021312

Bland JM, Altman DG: Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1986, i: 307–310.

Bland JM, Altman DG: Comparing methods of measurement: why plotting difference against standard method is misleading. Lancet 1995, 346: 1085–1087. 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)91748-9

McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr, Raczek AE: The MOS 36-Item short-form health survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care 1993, 31: 247–263. 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006

Liang MH, Larson MG, Cullen KE, Schwartz JA: Comparative measurement efficiency and sensitivity of five health status instruments for arthritis research. Arthritis Rheum 1985, 28: 542–547. 10.1002/art.1780280513

Prevoo ML, Hof MA V ’t, Kuper HH, Van Leeuwen MA, Van De Putte LB, Van Riel PL: Modified disease activity scores that include twenty-eight-joint counts: development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1995, 38: 44–48. 10.1002/art.1780380107

Fransen J, van Riel PL: The disease activity score and the EULAR response criteria. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2005, 23: S93-S99.

Deng N, Ware J: Using bootstrap confidence intervals to compare relative validity coefficients: an example with PRO measures of chronic kidney disease (CKD) impact. Value Health 2012, 15: A159.

Dorans NJ: Equating, concordance, and expectation. Applied Psychological Measurement 2004, 28: 227–246. 10.1177/0146621604265031

McHorney CA: Use of item response theory to link 3 modules of functional status items from the asset and health dynamics among the oldest old study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2002, 83: 383–394. 10.1053/apmr.2002.29610

Bjorner JB, Kosinski M, Ware JE Jr: Using item response theory to calibrate the Headache Impact Test (HIT) to the metric of traditional headache scales. Qual Life Res 2003, 12: 981–1002. 10.1023/A:1026123400242

Holzner B, Bode RK, Hahn EA, Cella D, Kopp M, Sperner-Unterweger B, Kemmler G: Equating EORTC QLQ-C30 and FACT-G scores and its use in oncological research. Eur J Cancer 2006, 42: 3169–3177. 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.08.016

Velozo CA, Byers KL, Wang YC, Joseph BR: Translating measures across the continuum of care: using Rasch analysis to create a crosswalk between the functional independence measure and the minimum data set. J Rehabil Res Dev 2007, 44: 467–478. 10.1682/JRRD.2006.06.0068

Haley SM, Ni P, Lai JS, Tian F, Coster WJ, Jette AM, Straub D, Cella D: Linking the activity measure for post acute care and the quality of life outcomes in neurological disorders. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011, 92: S37-S43. 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.01.026

Fischer HF, Wahl I, Fliege H, Klapp BF, Rose M: Impact of cross-calibration methods on the interpretation of a treatment comparison study using 2 depression scales. Med Care 2012, 50: 320–326. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31822945b4

Askew RL, Kim J, Chung H, Cook KF, Johnson KL, Amtmann D: Development of a crosswalk for pain interference measured by the BPI and PROMIS pain interference short form. Qual Life Res 2013. (2013 Mar 29. [Epub ahead of print])

Noonan VK, Cook KF, Bamer AM, Choi SW, Kim J, Amtmann D: Measuring fatigue in persons with multiple sclerosis: creating a crosswalk between the modified fatigue impact scale and the PROMIS fatigue short form. Qual Life Res 2012, 21: 1123–1133. 10.1007/s11136-011-0040-3

Fries JF, Krishnan E, Bruce B: Items, instruments, crosswalks, and PROMIS. J Rheumatol 2009, 36: 1093–1095. 10.3899/jrheum.090320

Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, Gershon R, Cook K, Reeve B, Ader D, Fries JF, Bruce B, Rose M: The patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS): progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med Care 2007, 45: S3-S11.

Fries JF, Cella D, Rose M, Krishnan E, Bruce B: Progress in assessing physical function in arthritis: PROMIS short forms and computerized adaptive testing. J Rheumatol 2009, 36: 2061–2066. 10.3899/jrheum.090358

Siemons L, Ten Klooster PM, Taal E, Glas CA, Van de Laar MA: Modern psychometrics applied in rheumatology–A systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2012, 13: 216. 10.1186/1471-2474-13-216

Tennant A, McKenna SP, Hagell P: Application of Rasch analysis in the development and application of quality of life instruments. Value Health 2004,7(Suppl 1):S22-S26.

Andrich D: Controversy and the Rasch model: a characteristic of incompatible paradigms? Med Care 2004, 42: I7-I16.

Bond TG, Fox CM: Applying the Rasch model: Fundamental measurement in the human sciences. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2007.

Stucki G, Stucki S, Bruhlmann P, Michel BA: Ceiling effects of the health assessment questionnaire and its modified version in some ambulatory rheumatoid arthritis patients. Ann Rheum Dis 1995, 54: 461–465. 10.1136/ard.54.6.461

Uhlig T, Haavardsholm EA, Kvien TK: Comparison of the health assessment questionnaire (HAQ) and the modified HAQ (MHAQ) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006, 45: 454–458. 10.1093/rheumatology/kei181

Wolfe F, Michaud K, Pincus T: Development and validation of the health assessment questionnaire II: a revised version of the health assessment questionnaire. Arthritis Rheum 2004, 50: 3296–3305. 10.1002/art.20549

Andresen EM, Fouts BS, Romeis JC, Brownson CA: Performance of health-related quality-of-life instruments in a spinal cord injured population. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999, 80: 877–884. 10.1016/S0003-9993(99)90077-1

Freeman JA, Hobart JC, Langdon DW, Thompson AJ: Clinical appropriateness: a key factor in outcome measure selection: the 36 item short form health survey in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000, 68: 150–156. 10.1136/jnnp.68.2.150

Kersten P, Mullee MA, Smith JA, McLellan L, George S: Generic health status measures are unsuitable for measuring health status in severely disabled people. Clin Rehabil 1999, 13: 219–228. 10.1191/026921599667206154

Lai SM, Perera S, Duncan PW, Bode R: Physical and social functioning after stroke: comparison of the Stroke Impact Scale and Short Form-36. Stroke 2003, 34: 488–493. 10.1161/01.STR.0000054162.94998.C0

Walsh M, Macgregor D, Stuckless S, Barrett B, Kawaja M, Scully MF: Health-related quality of life in a cohort of adult patients with mild hemophilia A. J Thromb Haemost 2008, 6: 755–761. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.02929.x

Katz P, Morris A, Yelin E: Subclinical disability in valued life activities among individuals with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2008, 59: 1416–1423. 10.1002/art.24110

Langston AL, Campbell MK, Fraser WD, Maclennan G, Selby P, Ralston SH: Clinical determinants of quality of life in Paget’s disease of bone. Calcif Tissue Int 2007, 80: 1–9.

Lovas K, Kalo Z, McKenna SP, Whalley D, Pentek M, Genti G: Establishing a standard for patient-completed instrument adaptations in Eastern Europe: experience with the Nottingham health profile in Hungary. Health Policy 2003, 63: 49–61. 10.1016/S0168-8510(02)00078-7

Johnson SR, Lee P: The HAQ disability index in scleroderma trials. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004, 43: 1200–1201. 10.1093/rheumatology/keh288

Zandbelt MM, Welsing PM, van Gestel AM, van Riel PL: Health assessment questionnaire modifications: is standardisation needed? Ann Rheum Dis 2001, 60: 841–845.

Wolfe F: A reappraisal of HAQ disability in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2000, 43: 2751–2761. 10.1002/1529-0131(200012)43:12<2751::AID-ANR15>3.0.CO;2-6

Krishnan E, Sokka T, Hakkinen A, Hubert H, Hannonen P: Normative values for the Health Assessment Questionnaire disability index: benchmarking disability in the general population. Arthritis Rheum 2004, 50: 953–960. 10.1002/art.20048

Louie GH, Reveille JD, Ward MM: Challenges comparing functional limitations in rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2009, 27: S83-S91.

Combe B, Landewe R, Lukas C, Bolosiu HD, Breedveld F, Dougados M, Emery P, Ferraccioli G, Hazes JM, Klareskog L, et al.: EULAR recommendations for the management of early arthritis: report of a task force of the European standing committee for international clinical studies including therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis 2007, 66: 34–45.

Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW, Breedveld FC, Boumpas D, Burmester G, Combe B, Cutolo M, de Wit M, Dougados M, et al.: Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis 2010, 69: 631–637. 10.1136/ard.2009.123919

Acknowledgment

This study was funded by the Dutch Arthritis Association, project number 11-1-203.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

PTK and MOV designed the study and drafted the manuscript. MOV and CG carried out the statistical analyses. BG, MR, JB, ET, PVR and MVDL supervised the study and the interpretation of the results. All authors critically reviewed, contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12955_2013_1239_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Additional file 1: Table S1: Item parameters and item level fit statistics for the Rasch (PCM) co-calibration of the HAQ-SDI and PF-10. Table S2. Item parameters and item level fit statistics for the Rasch (PCM) co-calibration of the HAQ-ADI and PF-10. Table S3. Item parameters and item level fit statistics for the two-parameter (GPCM) co-calibration of the HAQ-SDI and PF-10. Table S4. Item parameters and item level fit statistics for the two-parameter (GPCM) co-calibration of the HAQ-ADI and PF-10. Table S5. Item parameters and item level fit statistics for the multidimensional (GPCM) co-calibration of the HAQ-SDI and PF-10. Table S6. Item parameters and item level fit statistics for the multidimensional (GPCM) co-calibration of the HAQ-ADI and PF-10. (DOCX 37 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

ten Klooster, P.M., Oude Voshaar, M.A., Gandek, B. et al. Development and evaluation of a crosswalk between the SF-36 physical functioning scale and Health Assessment Questionnaire disability index in rheumatoid arthritis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 11, 199 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-11-199

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-11-199