Abstract

Background

Numerous primary care innovations emphasize patient-centered processes of care. Within the context of these innovations, greater understanding is needed of the relationship between improvements in clinical endpoints and patient-centered outcomes. To address this gap, we evaluated the association between glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) and diabetes-specific quality of life among patients completing diabetes self-management programs.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study nested within a randomized comparative effectiveness trial of diabetes self-management interventions in 75 diabetic patients. Multiple linear regression models were developed to examine the relationship between change in HbA1c from baseline to one-year follow-up and Diabetes-39 (a diabetes-specific quality of life measure) at one year.

Results

HbA1c levels improved for the overall cohort from baseline to one-year follow-up (t (74) = 3.09, p = .0029). One-year follow up HbA1c was correlated with worse overall quality of life (r = 0.33, p = 0.004). Improvements in HbA1c from baseline to one-year follow-up were associated with greater D-39 diabetes control (β = 0.23, p = .04) and D-39 sexual functioning (β = 0.25, p = .03) quality of life subscales.

Conclusions

Improvements in HbA1c among participants completing a diabetes self-management program were associated with better diabetes-specific quality of life. Innovations in primary care that engage patients in self-management and improve clinical biomarkers, such as HbA1c, may also be associated with better quality of life, a key outcome from the patient perspective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Diabetes Mellitus is among the most prevalent chronic illnesses in the United States, affecting nearly 24 million Americans [1]. In response to the Institute of Medicine’s calls for patient-centeredness [2], innovations in diabetes care have increasingly made patients’ perspectives central to the process and outcomes of care. These advances, which include the Chronic Care Model [3], the Patient-Centered Medical Home [4], and various patient-engagement interventions [5, 6], all focus on patient-centeredness in the process of care. However, there is a need to move beyond the process of care and develop patient-centered outcomes to assess the impact of these innovations from the patient perspective.

As with many chronic diseases, diabetes patients are less concerned with clinical biomarkers [7] such as hemoglobin A1c, blood pressure, or lipid levels, and are more concerned with physical and social function, emotional and mental health, and the burden of illness and treatments on daily life [8]. Quality of life measures, which include many of these domains [9] are thus more meaningful and relevant outcomes from the patient perspective. The development of quality of life measures that are associated with future clinical outcomes would enhance shared decision making by framing treatment options in a context that is pertinent to patients [10].

In diabetes care, general health status measures such as the SF-36 and the EQ-5D are commonly used to assess patients’ quality of life [11–18]. Although these measures are useful in comparing patient health status across different illnesses, they often cannot capture distinctive aspects of specific diseases [19]. Quality of life measures that are disease-specific and associated with clinical outcomes have been developed in other chronic illnesses. For instance, a number of disease-specific quality of life measures in cardiovascular disease [10, 20–22] and cancer [23–28] are predictive of subsequent morbidity and mortality. Diabetes places significant self-management responsibility on patients, and thus warrants the development and validation of clinically relevant and patient-centered quality of life measures. Recent structured reviews [9, 29, 30] have identified several disease-specific quality of life measures for diabetes. Unfortunately, attempts to understand the association between these quality of life measures and common clinical biomarkers, such as HbA1c, have been inadequate [9, 29, 30].

We conducted a retrospective cohort study nested within a randomized comparative effectiveness trial of diabetes self-management interventions to investigate the association of HbA1c and diabetes-specific quality of life. We evaluated the relationship between diabetes-specific quality of life and HbA1c both before and after participants completed diabetes self-management programs.

Methods

Study design

This study was a retrospective cohort study nested within a pilot randomized comparative effectiveness trial conducted among diabetic patients at the Michael E. Debakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MEDVAMC). The trial randomized eligible participants to the Empowering Patients in Chronic Care (EPIC) goal setting intervention or to a diabetes self-management and nutrition education intervention. The primary study was conducted among 50–90 year old type II diabetes mellitus patients with primary care providers (PCPs) within the VA healthcare system. This secondary analysis included all participants from the original study who had HbA1c ≥ 7.0% at baseline, completed either of the two self-management programs, had HbA1c measurements in the VA clinic database at one-year follow-up, and returned completed one-year follow-up questionnaires.

Diabetes self-management programs

All participants in our retrospective cohort completed one of two diabetes self-management programs. Both programs were conducted in group settings, included diabetes self-management education, and focused on educating participants about key clinical indicators in diabetes and the importance of integrating patient self-management into daily life. Each program included a ten minute one-on-one session with either a clinician or a diabetes educator to go over participants’ individual HbA1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol levels. The aim of the 1-on-1 personal sessions in both programs was to help participants individualize the diabetes self-management information. The Empowering Patients in Chronic Care (EPIC) intervention included didactic and problem-based discussions on goal-setting and action planning as well as patient-physician communication. The traditional diabetes education intervention included information on diabetes medications, associated health problems, meal preparation, and portion size and control. The complete methodology of the randomized comparative effectiveness study has been published elsewhere [6].

Data collection

All data used in this study were collected during the EPIC pilot randomized comparative effectiveness trial after approval from the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board and the MEDVAMC research and development committee. No additional data were collected for this retrospective cohort study.

Clinical information, including hemoglobin A1c and body mass index, was collected and then extracted from participants’ medical record in the MEDVAMC clinic database. Participants also completed questionnaires with a variety of self-reported data at baseline and one-year. Diabetes-related burden of illness was assessed at baseline as a proxy for diabetes-specific quality of life using a measure adapted from the Diabetes Care Profile Section VII [19]. This 13-item measure asks participants about aspects of their daily lives that diabetes interferes with, the burden of diabetes on personal finances, and how difficult life with diabetes is. Responses are along a 5-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating a greater diabetes-related burden of illness. Individual diabetes burden of illness scores are calculated as the mean of all items, and thus range from 1–5. A co-morbidity score was determined using a measure derived from the Deyo modification of the Charlson Comorbidity Index [31].

Diabetes-39: A diabetes specific quality of life questionnaire

Diabetes-related quality of life was assessed at one-year using the Diabetes-39 [32]. This 39-item self-administered instrument measures patients’ self-assessed quality of life, and includes 5 domains: diabetes control, anxiety and worry, social burden, sexual functioning, and energy and mobility. Respondents were asked “how much was the quality of your life affected by” a wide range of aspects of diabetes illness and its treatments in the past month. Possible responses are along a 7-point scale, and range from “Not affected at all” (=1) to “Extremely affected” (=7). Domain scores were calculated by summing the responses and then applying a linear transformation to a 0–100 scale. An overall quality of life score was calculated using all 39 items in the questionnaire. Scores closer to 0 indicate a better quality of life. The instrument has undergone tests for internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.81–0.93; item-total correlation = 0.50–0.84), construct validity using the SF-36 Health Status Questionnaire, and a factor analysis, which found that five factors accounted for 90% of variance [33].

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics to characterize the cohort at baseline. Normality of continuous variables was assessed with Shapiro-Wilks test. Continuous variables were described using means, standard deviations, medians, and interquartile ranges, whereas categorical variables were described using counts and percents. Those who returned the follow-up survey at one year were compared to those who did not return the survey on demographic and clinical characteristics using Fishers Exact Test and the Wilcoxon Mann–Whitney test. The Wilcoxon signed rank sum test was used to compare change in HbA1c from baseline to one-year follow-up and the Spearman Brown correlation (r sb ) was calculated to assess the relationship between one-year HbA1c and overall quality of life.

Multiple linear regression models were created to assess the relationships between change in HbA1c from baseline to one-year and quality of life at one-year. Change in HbA1c was calculated by subtracting baseline scores from 1 year scores. Therefore, higher scores indicated less improvement in HbA1c. Six regression models were conducted to separately predict the overall quality of life score and each of the five quality of life subscales. Treatment group (where diabetes education = 0 and EPIC intervention = 1) and baseline burden of illness were included as covariates in all six models. Because baseline Diabetes-39 quality of life scores were not available, baseline burden of illness served as a proxy for baseline quality of life. All analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Sample characteristics

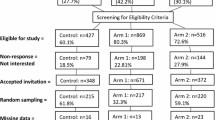

We identified a cohort of participants completing one of two diabetes self-management programs as part of a randomized comparative effectiveness trial. The current study draws from the 94 participants who were consented and enrolled as part of the original comparative effectiveness trial. We excluded 14 participants from our cohort who did not return one-year follow-up questionnaires. Four additional participants were excluded for having baseline HbA1c below 7.0%, and one participant was excluded due to an incomplete D-39 questionnaire. A total of 75 participants were included in the analytical cohort for this study.

Table 1 describes the baseline characteristics of the study cohort. Those with baseline HbA1c of at least 7.0% who did not return the follow-up questionnaire (n = 11) were not significantly different from study includes (n = 75) on any of the demographic or clinical characteristics reported in Table 1 (all p s > .05, data for non-respondents not reported). The cohort was predominantly older men of diverse education and racial/ethnic backgrounds, with multiple morbidities and elevated BMI and HbA1c levels at baseline.

Outcome measures

Significant improvements in HbA1c levels were observed for the cohort from baseline to one-year follow-up, S = −574, p = .001. At follow-up, mean scores for overall quality of life and diabetes control, anxiety and worry, and energy and mobility subscale scores were similar to each other. Social burden subscale scores were better than overall quality of life scores, while sexual functioning subscale scores were worse than overall quality of life scores.

Higher one-year HbA1c scores were associated with worse overall quality of life (r sb = 0.37, p = 0.001). We conducted a series of six multiple linear regression models to assess the relationship between change in HbA1c from baseline to one-year and Diabetes-39 quality of life (overall and for each subscale) at one-year. Results are presented in Table 2, with all models adjusting for burden of illness at baseline and treatment group. Irrespective of intervention group assignment and baseline burden of illness, improved HbA1c levels from baseline to one-year follow-up were significantly associated with greater quality of life on the diabetes control (β = 0.23, p = .04) and sexual function subscales (β = 0.25, p = .03). Change in HbA1c from baseline to one-year was not associated with greater overall quality of life or the anxiety/worry, social burden, or energy and mobility subscales. The R2 values for the diabetes control, sexual function, and energy and mobility subscale models were significant, indicating that these models explain a significant amount of the variability in their respective diabetes-specific quality of life subscales.

Discussion

We constructed a retrospective cohort of participants drawn from a randomized comparative effectiveness study to evaluate the relationship between change in HbA1c and Diabetes-39 quality of life. HbA1c at one-year follow-up was significantly associated with overall quality of life on the Diabetes-39. Our multiple linear regression models suggest that improvements in HbA1c among patients completing diabetes self-management interventions are significantly associated with increased quality of life on the diabetes control and sexual functioning subscales of the Diabetes-39. No association was established between changes in HbA1c and the anxiety and worry, social burden, and energy and mobility subscales. Baseline burden of illness, a proxy for baseline quality of life, predicted overall quality of life as well as all subscales of the Diabetes-39, as expected.

This study firmly establishes the relationship between improved HbA1c, a critical clinical biomarker in diabetes, and the Diabetes-39, a patient-centered diabetes-specific quality of life measure among patients completing a self-management education program. Several previous studies have attempted to explore the relationship between clinical indicators, such as HbA1c, and a variety of diabetes-specific quality of life measures [31, 34–40]. Unfortunately, these associations have been weak [41] or nonexistent [42], present for only very few of a scale’s domains [36], or are specific to type 1 diabetes only [34, 35]. Further, prior studies report on measures that have poor evidence for validity and reliability [32, 35, 36, 41], focus on singular aspects of quality of life (e.g., distress [37, 38, 41]), ignore key components of quality of life such as physical and social functioning [9], or include several items that are not diabetes-specific [9]. Additionally, several reviews of diabetes-specific quality of life measures [9, 29, 30] have recognized the lack of empirical evidence on the responsiveness of these scales to changes in health status.

This analysis of HbA1c and diabetes-specific quality of life addresses many of the limitations of prior studies. The Diabetes-39 diabetes-specific quality of life measure has been recommended for use in research and clinical settings by all of the aforementioned reviews of diabetes-specific quality of life measures [9, 29, 30]. The instrument has good evidence for validity and reliability, includes several domains that cover many aspects of quality of life, and is applicable to a wide population of patients [9, 29, 30, 33]. The Diabetes-39 is one of few diabetes-specific quality of life measures that have been shown to be responsive to changes in health status [39]. Further, this instrument does not impose a definition of quality of life upon respondents, but instead allows patients to frame responses in the context of their own personal conceptualization of quality of life. Also, patients were directly involved in the selection of items for the questionnaire [33]. These attributes make the instrument highly patient-centered, one of the most critical components to any patient-assessed quality of life measure. Thus, our study focuses on a diabetes-specific quality of life measure that is a prime candidate for analysis.

Our statistical methods also address several prior studies’ shortcomings. While most previous attempts to examine the relationship between HbA1c and quality of life used simple linear correlations [34, 41, 42], our analyses included predictive linear regression models. This allows for a more robust analysis and provides a quantification of the impact of HbA1c on quality of life. To our knowledge, two prior studies have employed linear regression models to assess this relationship [37, 38]. However, one study [38] grouped continuous HbA1c data into two groups. This reduces a model’s ability to quantify the effect of changes in HbA1c on quality of life, and diminishes the overall robustness of the model. A second study [37] modeled HbA1c as the primary dependent variable. This is not in line with the Institute of Medicine’s vision [2] in which patient-centered measures, such as quality of life, are the ultimate outcomes of care. Our analysis included a regression of continuous HbA1c data with quality of life as the primary outcome.

Few prior studies have examined the relationship between clinical indicators and diabetes-specific quality of life measures among participants who all completed diabetes self-management programs. These programs were deeply embedded in primary care. One program was led by a primary care physician, while the other was led by nurse educators and registered dieticians. The latter model represents the type of delivery system redesign that is characteristic to many primary care innovations [3, 4]. Our examination of the relationship between clinical indicators and quality of life outcomes in the context of patient-centered diabetes self-management programs demonstrates that HbA1c improvements among participants in these programs are associated with better quality of life. Previous studies have included diabetes-specific quality of life among outcome measures [40, 43]. These studies approach both quality of life and HbA1c as distinct outcomes, and do not explore the association between the two variables. Unlike prior studies, our study examines the relationship between changes in HbA1c and diabetes-specific quality of life. In the post-ACCORD era, there has been reduced emphasis on intensive HbA1c control [44]. However, the current study suggests that improved HbA1c resulting from diabetes self-management interventions is associated with better diabetes-specific quality of life. Thus, HbA1c control is relevant to patient-centered outcomes and should remain a valuable goal in diabetes care.

There were limitations to our study. A sample size of 75 limited the range of analytic strategies that could be employed. The sample size may also have affected the power of our analyses, which may account for the weak association between changes in HbA1c and some of the Diabetes-39 subscales. The generalizability of our study may also be limited. Our sample is reflective of the United States Veterans Administration patient population, consisting largely of older patients who are predominantly male, of older age, and have significant co-morbidities. Further, all of the participants in our cohort participated in at least one diabetes self-management program. Thus, we were unable to assess the impact of participation in these programs on quality of life as compared with patients who did not participate in any self-management programs. Additionally, the lack of Diabetes-39 data at baseline precluded an examination of the responsiveness of this diabetes-specific quality of life measure over time. However, our analysis does include HbA1c data from multiple time points and includes a measure of burden of illness at baseline. Many previous studies used cross-sectional data from one time point [34, 37, 41, 42]. Our analyses included HbA1c data from both before and after participation in diabetes self-management programs.

Future studies should be certain to collect quality of life data both before and after diabetes self-management programs so that the responsiveness of quality of life measures can be assessed. Subsequent studies should also include larger, more diverse samples to ensure adequate power and generalizability. The inclusion of a control group that does not receive any programs beyond routine care may also allow for future examinations of the impact of diabetes-self management programs on quality of life.

Conclusion

Improved HbA1c levels among participants in diabetes self-management programs are associated with higher diabetes-specific quality of life scores. These findings suggest that innovations in primary care focused on patient engagement may not only improve traditional clinical outcomes, but are associated with better patient-centered quality of life outcomes.

Authors’ information

AK is an MD/MPH candidate at Baylor College of Medicine and the University of Texas School of Public Health. AN is the an investigator in the Health Decision-Making and Communication Program, Houston VA Health Services Research and Development CoE, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center. AN is also an Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Section of Health Services Research, Baylor College of Medicine and Adjunct Assistant Professor, Division of Health Promotion and Behavioral Sciences, School of Public Health, The University of Texas Health Sciences Center at Houston. AB is a Programmer in the Design and Analysis Program, Houston VA Health Services Research and Development CoE, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center and an Instructor in the Department of Medicine, Section of Health Services Research, Baylor College of Medicine. JS is a Professor of Health Economics, at the University Texas School of Public Health and at the University of Texas Medical School, Center for Clinical Research Evidence-Based Medicine, and Adjunct Professor, Department of Economics, Rice University. RS is a Research Professor in Medicine at Texas A&M University and Director, Health Communication and Decision-Making Program in the Houston Center for Quality of Care and Utilization Studies, Baylor College of Medicine. MP is the Associate Director of Evaluation for the University of Texas Prevention Research Center and an Assistant Professor at The University of Texas School of Public Health.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: National diabetes fact sheet: general information and national estimates on diabetes in the United States. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA; 2008. [http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/pdf/ndfs_2007.pdf]

Institute of Medicine: Crossing the Quality Chasm Preface and Executive Summary. In In Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. The National Academies Press; 2001:1–22.

Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M: Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. The Milbank Quarterly 1996, 74(4):511–544. 10.2307/3350391

American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), American College of Physicians (ACP), American Osteopathic Association (AOA): Joint principles of the patient-centered medical home.: American Academy of Family Physicians 2007.

Bodenheimer T, Handley MA: Goal-setting for behavior change in primary care: An exploration and status report. Patient Education and Counseling 2009, 76(2):174–180. 10.1016/j.pec.2009.06.001

Naik AD, Palmer N, Petersen NJ, Street RL, Rao R, Suarez-Almazor ME, Haidet P: Comparative Effectiveness of Goal-setting in Diabetes Group Clinics: Randomized Clinical Trial. Arch Intern Med 2011, 171(5):453–9. 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.70

Krumholz HM: Outcomes research: Generating evidence for best practice and policies. Circulation 2008, 118(3):309–318. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.690917

Barr JT: The outcomes movement and health status measures. Journal of Allied Health 1995, 24(1):13–28.

Watkins K, Connell CM: Measurement of health-related QOL in diabetes mellitus. PharmacoEconomics 2004, 22(17):1109–1126. 10.2165/00019053-200422170-00002

Spertus JA: Evolving applications for patient-centered health status measures. Circulation 2008, 118(20):2103–2110. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.747568

Tapp RJ, O'Neil A, Shaw JE, Zimmet PZ, Oldenburg BF, AusDiab Study Group: Is there a link between components of health-related functioning and incident impaired glucose metabolism and type 2 diabetes? The Australian Diabetes Obesity and Lifestyle (AusDiab) Study. Diabetes Care 2010, 33(4):757–762. 10.2337/dc09-1107

Logtenberg SJ, Kleefstra N, Houweling ST, Groenier KH, Gans RO, Bilo HJ: Health-related quality of life, treatment satisfaction, and costs associated with intraperitoneal versus subcutaneous insulin administration in type 1 diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2010, 33(6):1169–1172. 10.2337/dc09-1758

Li CL, Chang HY, Lu JR: Health-related quality of life predicts hospital admission within 1 year in people with diabetes: A nationwide study from taiwan. Diabetic Medicine: A Journal of the British Diabetic Association 2009, 26(10):1055–1062. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02818.x

Merlino G, Valente M, Serafini A, Fratticci L, Del Giudice A, Piani A, Noacco C, Gigli GL: Effects of restless legs syndrome on quality of life and psychological status in patients with type 2 diabetes. The Diabetes Educator 2010, 36(1):79–87. 10.1177/0145721709351252

Hayashino Y, Fukuhara S, Akiba T, Akizawa T, Asano Y, Saito S, Kurokawa K: Low health-related quality of life is associated with all-cause mortality in patients with diabetes on haemodialysis: The japan dialysis outcomes and practice pattern study. Diabetic Medicine: A Journal of the British Diabetic Association 2009, 26(9):921–927. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02800.x

Ziegler D, Movsesyan L, Mankovsky B, Gurieva I, Abylaiuly Z, Strokov I: Treatment of symptomatic polyneuropathy with actovegin in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2009, 32(8):1479–1484. 10.2337/dc09-0545

Ose D, Wensing M, Szecsenyi J, Joos S, Hermann K, Miksc A: Impact of primary care-based disease management on the health-related quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes and comorbidity. Diabetes Care 2009, 32(9):1594–1596. 10.2337/dc08-2223

Clarke PM, Hayes AJ, Glasziou PG, Scott R, Simes J, Keech AC: Using the EQ-5D index score as a predictor of outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. Medical Care 2009, 47(1):61–68. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181844855

Anderson RM, Fitzgerald JT, Wisdom K, Davis WK, Hiss RG: A comparison of global versus disease-specific quality-of-life measures in patients with NIDDM. Diabetes Care 1997, 20(3):299–305. 10.2337/diacare.20.3.299

Spertus JA, Tooley J, Jones P, Poston C, Mahoney E, Deedwania P, Hurley S, Pitt B, Weintraub WS: Expanding the outcomes in clinical trials of heart failure: The quality of life and economic components of EPHESUS (EPlerenone's neuroHormonal efficacy and SUrvival study). Am Hear J 2002, 143(4):636–642. 10.1067/mhj.2002.120775

Carson P, Tam SW, Ghali JK, Archambault WT, Taylor A, Cohn JN, Braman VM, Worcel M, Anand IS: Relationship of quality of life scores with baseline characteristics and outcomes in the african-american heart failure trial. J Card Fail 2009, 15(10):835–842. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.05.016

Moser DK, Yamokoski L, Sun JL, Conway GA, Hartman KA, Graziano JA, Binanay C, Stevenson LW, Escape Investigators: Improvement in health-related quality of life after hospitalization predicts event-free survival in patients with advanced heart failure. J Card Fail 2009, 15(9):763–769. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.05.003

Montazeri A: Quality of life data as prognostic indicators of survival in cancer patients: An overview of the literature from 1982 to 2008. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2009, 7: 102. 10.1186/1477-7525-7-102

Coates A, Gebski V, Bishop JF, Jeal PN, Woods RL, Snyder R, Tattersall MH, Byrne M, Harvey V, Gill G: Improving the quality of life during chemotherapy for advanced breast cancer. A comparison of intermittent and continuous treatment strategies. N Engl J Med 1987, 317(24):1490–1495. 10.1056/NEJM198712103172402

Herndon JE, Fleishman S, Kornblith AB, Kosty M, Green MR, Holland J: Is quality of life predictive of the survival of patients with advanced nonsmall cell lung carcinoma? Cancer 1999, 85(2):333–340. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19990115)85:2<333::AID-CNCR10>3.0.CO;2-Q

Efficace F, Bottomley A, Smit EF, Lianes P, Legrand C, Debruyne C, Schramel F, Smit HJ, Gaafar R, Biesma B, Manegold C, Coens C, Giaccone G, Van Meerbeeck J, EORTC Lung Cancer Group and Quality of Life Unit: Is a patient's self-reported health-related quality of life a prognostic factor for survival in non-small-cell lung cancer patients? A multivariate analysis of prognostic factors of EORTC study 08975. Annals of Oncology: Official Journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology/ESMO 2006, 17(11):1698–1704. 10.1093/annonc/mdl183

Eton DT, Fairclough DL, Cella D, Yount SE, Bonomi P, Johnson DH, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group: Early change in patient-reported health during lung cancer chemotherapy predicts clinical outcomes beyond those predicted by baseline report: Results from eastern cooperative oncology group study 5592. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2003, 21(8):1536–1543. 10.1200/JCO.2003.07.128

Lis CG, Gupta D, Grutsch JF: Patient satisfaction with quality of life as a predictor of survival in pancreatic cancer. International Journal of Gastrointestinal Cancer 2006, 37(1):35–44. 10.1385/IJGC:37:1:35

Garratt AM, Schmidt L, Fitzpatrick R: Patient-assessed health outcome measures for diabetes: A structured review. Diabetic Medicine: A Journal of the British Diabetic Association 2002, 19(1):1–11. 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00650.x

El Achhab Y, Nejjari C, Chikri M, Lyoussi B: Disease-specific health-related quality of life instruments among adults diabetic: A systematic review. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 2008, 80(2):171–184. 10.1016/j.diabres.2007.12.020

Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA: Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 1992, 45(6):613–619. 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8

Fitzgerald JT, Davis WK, Connell CM, Hess GE, Funnell MM, Hiss RG: Development and validation of the diabetes care profile. Evaluation & the Health Professions 1996, 19(2):208–230. 10.1177/016327879601900205

Boyer JG, Earp JA: The development of an instrument for assessing the quality of life of people with diabetes: Diabetes-39. Medical Care 1997, 35(5):440–453. 10.1097/00005650-199705000-00003

Bott U, Muhlhauser I, Overmann H, Berger M: Validation of a diabetes-specific quality-of-life scale for patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 1998, 21(5):757–769. 10.2337/diacare.21.5.757

Mannucci E, Ricca V, Bardini G, Rotella CM: Well-being enquiry for diabetics: a new measure of diabetes-related quality of life. Diabetes, Nutrition, and Metabolism 1996, 2(9):89–102.

Hammond GS, Aoki TT: Measurement of Health Status in diabetic patients: diabetes impact measurement scales. Diabetes Care 1992, 15(4):469–477. 10.2337/diacare.15.4.469

Polonsky WH, Anderson BJ, Lohrer PA, Welch G, Jacobson AM, Aponte JE, Schwartz CE: Assessment of diabetes-related distress. Diabetes Care 1995, 18(6):754–760. 10.2337/diacare.18.6.754

Herschbach P, Duran G, Waadt S, Zettler A, Amm C, Marten-Mittag B: Psychometric properties of the questionnaire on stress in patients with diabetes–revised (QSD-R). Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association 1997, 16(2):171–174.

Lee LJ, Fahrbach JL, Nelson LM, McLeod LD, Martin SA, Sun P, Weinstock RS: Effects of insulin initiation on patient-reported outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes: Results from the DURABLE trial. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 2010, 89(2):157–66. 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.04.002

Lowe J, Linjawi S, Mensch M, James K, Attia J: Flexible eating and flexible insulin dosing in patients with diabetes: Results of an intensive self management course. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 2008, 80(3):439–43. 10.1016/j.diabres.2008.02.003

Carey MP, Jorgensen RS, Weinstock RS, Sprafkin RP, Lantinga LJ, Carnrike CL, Baker MT, Meisler AW: Reliability and validity of the appraisal of diabetes scale. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 1991, 14(1):43–51. 10.1007/BF00844767

Polonsky WH, Fisher L, Earles J, Dudl RJ, Lees J, Mullan J, Jackson RA: Assessing psychosocial distress in diabetes: Development of the diabetes distress scale. Diabetes Care 2005, 28(3):626–631. 10.2337/diacare.28.3.626

DAFNE Study Group: Training in flexible, intensive insulin management to enable dietary freedom in people with type 1 diabetes: dose adjustment for normal eating (DAFNE) randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2002, 325(7367):746. 10.1136/bmj.325.7367.746

Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes Study Group: Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008, 358(24):2545–59.

Acknowledgements

The EPIC study was supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Centers for Research and Education on Therapeutics (U18HS016093; principalinvestigator, Dr Suarez-Almazor). Additional support for the EPIC Study was provided by a Clinical Scientist Development Award from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (principal investigator, Dr Naik). Dr Naik received additional support from the National Institute of Aging (K23AG027144) and the Houston Health Services Research and Development Center of Excellence (HFP90-020) at the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AK and AN conceived of the study and participated in its design. AK drafted the manuscript. AB conducted statistical analysis and helped draft the manuscript. AN participated in study conception and design, helped draft the manuscript, and conducted the parent study from which data for this study was derived. JS, RS, and MP contributed to interpretation of data, revising manuscript critically, and final approval of the version submitted to the journal. All authors read and approved the final manuscript

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Khanna, A., Bush, A.L., Swint, J.M. et al. Hemoglobin A1c improvements and better diabetes-specific quality of life among participants completing diabetes self-management programs: A nested cohort study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 10, 48 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-10-48

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-10-48