Abstract

Background

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is a neurodegenerative disease which runs its course for the remainder of the patient's life frequently causing disability of varying degrees. Negative effects on Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) are well documented and a subject of clinical study. The Multiple Sclerosis QOL 54 (MSQOL-54) questionnaire was developed to measure HRQOL in patients with MS. It is composed of 54 items, and is a combination of the SF-36 and 18 disease-specific items.

Objective

The objective of this project was to translate the MSQOL-54 into French Canadian, and to make it available to the Canadian scientific community for clinical research and clinical practice.

Methods

Across all French speaking regions, there are occurrences of variation. They include the pronunciation, sentence structure, and the lexicon, where the differences are most marked. For this reason, it was decided to translate the US original MSQOL-54 into French Canadian instead of adapting the existing French version. The SF-36 has been previously validated and published in French Canadian, therefore the translation work was performed solely on the 18 MS specific items. The translation followed an internationally accepted methodology into 3 steps: forward translation, backward translation, and patients' cognitive debriefing.

Results

Instructions and Items 38, 43, 45 and 49 were the most debated. Problematic issues mainly resided in the field of semantics. Patients' testing (n = 5) did not reveal conceptual problems. The questionnaire was well accepted, with an average time for completion of 19 minutes.

Conclusion

The French Canadian MSQOL-54 is now available to the Canadian scientific community and will be a useful tool for health-care providers to assess HRQOL of patients with MS as a routine part of clinical practice. The next step in the cultural adaptation of the MSQOL-54 in French Canadian will be the evaluation of its psychometric properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by chronic inflammation, demyelination, and scarring of the central nervous system. Symptoms include weakness, fatigue, sensory loss, vertigo, lack of coordination, impotence or sexual dysfunction, urinary incontinence, optic atrophy, dysarthria, and mental problems [1, 2]. The average age at onset of MS is 30 years, and the disease runs its course for the remainder of the patient's life frequently causing disability of varying degrees [1]. The prevalence of MS varies with both geography and ethnic background with women twice as likely to be afflicted as men [3]. With an estimated 35,000 sufferers, Canada is considered a high frequency area with an average of between 55 and 202 per 10,000 persons [4].

While the effect of MS on life expectancy remains controversial, the disease's negative effect on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is documented and a topic currently undergoing clinical study [5–7]. Several studies have shown that HRQoL assessments provide unique information not measured by the Kurtzke's Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS), the commonly used outcome measure of impairment disability for MS patients [8–10]. As an alternative indicators of the impact of the disease on a patient's life, self-reported HRQoL focuses more attention on MS patients as a whole, in addition to focusing on physical problems [11, 12].

From the perspective of patients' organizations and regulatory agencies HRQOL assessments are increasingly seen as additional sources of information on the safety and efficacy of treatments, particularly important in chronic progressive, disabling diseases for which there is no cure [13]. Although the main use of HRQoL instruments has been in the context of clinical trials, the observation that measures of patients' perception of their health do not overlap with clinician assessments of disability reinforces the importance of developing HRQoL instruments for use in routine clinical practice [14, 15]. Rothwell et al. have shown that physical disability may not always be the main determinant of overall health related quality of life. Furthermore, their study showed that patient with MS are less concerned than their clinicians about physical disability in their illness [15]. Provinciali et al. have shown that including HRQoL in their multidimensional assessment protocol provides a detailed and sensitive evaluation of patients' disability profile and perceived difficulties thereby allowing clinicians to develop a care program tailored to each individual's needs [16]. HRQoL measures can also serve as screening instruments for patients reporting changes in symptom severity or functional ability. The quality of life data can be used to involve patients and family members in clinical decision-making [17].

The MSQOL-54 questionnaire was developed to measure HRQoL in patients suffering from multiple sclerosis [18]. Composed of the Short Form 36 Item Health survey (Short Form-36 or SF-36) [19, 20] and 18 disease specific items, this 54-item self-report measure combines the strength of generic and disease specific approaches to HRQoL measurement. By complementing the SF-36 with questions focusing on the specific domains affected by MS it becomes possible to compare the HRQOL of a patient suffering from MS with the HRQoL of the general population and the HRQOL of patients with other diseases. In routine clinical practice the instrument could be used to evaluate the differences in HRQoL of individuals at various stages of MS.

The MSQOL-54 has been used in the United States and has proven a valuable instrument for measuring HRQoL in MS [21–23]. The questionnaire has also been translated into both Italian [24] and French [25, 26].

The objective of this study was to translate the MSQOL-54 into French Canadian, and to make it available to the Canadian scientific community for clinical research and clinical practice.

Methodology

Background

According to the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis [27], every language embodies its own vision of the world, a prism through which its speakers inevitably view, for instance, their own health. If true, this hypothesis would indicate that a valid translation is impossible. Fortunately, this is not the case. We are in fact able to make the leaps of logic necessary to comprehend the complex ideas put forth by a foreign society [28], and translation techniques are available to remove the difficulties hindering the optimal transfer of the information, emotion, and stylistic content of the original message [29].

Conducted using an internationally accepted methodology, the cultural adaptation of an HRQoL questionnaire encompasses two essential stages: a translation stage ensuring linguistic validity of the questionnaire in the new language and the evaluation of the psychometric properties of the questionnaire or psychometric validation [30]. The two are complementary and indispensable in demonstrating the equivalence between the original and the translated questionnaires.

This paper describes the linguistic validation of the 18 MS specific questions (i.e. #37 to #54) in French Canadian since the SF-36 has been previously translated, psychometrically validated and published in French Canadian [31] and is currently used in the Canadian National Population Survey [32].

More than one hundred million people of very diverse cultures speak French across the world. Quebec, the principal French-speaking center in North America, constitutes a significant member of this speech community. As is the case for all languages, there are occurrences of variation inside the French language. The variation is composite: it includes the pronunciation (the accents), sentence structure, and the lexicon, where the differences are most marked [33]. For this reason we translated the 18 MS specific questions (i.e. #37 to #54) of the original US MSQOL-54 into French Canadian instead of adapting the existing French version [26].

Linguistic validation

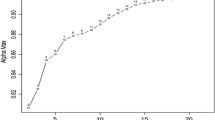

In general, there are four major stages (figure 1) involved in a linguistic validation: forward translation, quality control through backward translation, test of understanding or cognitive debriefing, international harmonization. Each stage helps to improve the quality of the translation in terms of the conceptual equivalence between the original and translated questionnaires and the ease of understanding of the patient. In this project, the linguistic validation of the 18 disease-specific questions of the MSQOL-54 was performed solely into French Canadian thereby removing the need for an International Harmonization process. The linguistic validation was carried out in Canada by a Project Manager based in Canada, under the supervision of Mapi Research Institute's Central Project Manager based in Lyon France.

Linguistic Validation – MAPI Research Institute process* *Adapted from: Mear I. Difficulties of international clinical trials: Cultural adaptation of quality of life questionnaires. In Chassany O, Caulin C, eds. Health-related quality of life and Patient-reported outcomes: Scientific and useful outcome criteria. Paris: Springer Verlag Publishers, 2002; 55–62.

STEP 1: Forward Translation

The aim of this first step was to translate the 18 disease specific questions (#37–54) of the original US MSQOL-54 questionnaire into French Canadian and produce a version that was semantically and conceptually as close as possible to the original questionnaire. Two qualified translators, native speakers of French Canadian, proficient in English and living in the target country, and the Local French Canadian Project Manager, performed this step. Each translator produced a forward translation of the original instrument into the target language without mutual consultation. The Local Project Manager reviewed the forward translations, compared them with the original and established a consensus version.

STEP 2: Backward Translation

Carried out with quality control in mind, the 18 French Canadian questions generated in step 1 were translated back into American English by one qualified translator, native speaker of English, proficient in French Canadian and living in Quebec. Following discussions between the translator, the Local Project Manager, and Mapi Research Institute's Central Project Manager, translation discrepancies were corrected in the French version to generate a version of the MSQOL-54 ready for testing by MS patients.

STEP 3: Cognitive Debriefing

The aim of this step was to check the French Canadian population's understanding and interpretation of the translated items and thereby validate the conceptual equivalence between the US and French Canadian versions. The French Canadian version of the questionnaire generated in step 2 was tested on five French Canadian subjects with multiple sclerosis. This stage led to the final French Canadian version of the MSQOL-54.

Results

What follows is an overview of the problems encountered and the solving process. Minor changes made for typographical or grammatical reasons are not discussed.

Use of masculine/feminine forms

As both gender populations will use these questionnaires both forms will be used in the translation wherever appropriate.

Title: "Multiple Sclerosis Quality of life (MSQOL-54)

It was suggested that "Questionnaire de Qualité de vie sur la sclérose en plaques" (Quality of Life Questionnaire on multiple sclerosis) was not satisfactory as the notion of "sur la sclérose en plaques" (on multiple sclerosis) was not idiomatic. As a result of the discussions between the French Canadian team and Mapi Research Institute it was decided that "Questionnaire de Qualité de vie dans la sclérose en plaques"(Quality of Life Questionnaire in multiple sclerosis) was more understandable and more accepted in spoken French Canadian.

Instructions

• First instruction sentence: "The survey asks you about your health and daily activities"

In French Canadian it is impossible to use a literal translation of the verb "to ask" in this context because in spoken French only a person can ask something of another person, a survey cannot. After discussion with the French Canadian consultant, it was decided to render "asks you about" as "porte sur" (concerns), a much more idiomatic verb in this sense.

• Second instruction sentence: "Answer every question by ticking the appropriate statement"

As it is not idiomatic to use the verb "tick" in French Canadian, it was decided to use "cocher" (cross), the usual way to mark answers in this language.

• Third instruction sentence: " If you are unsure how to answer a question, please give the best answer you can."

The notion "If you are unsure…" was initially translated as " En cas d'hésitation…" (In case of hesitation…). However, subsequent to review and recommendation, it was decided to change this to "En cas de doute…"(In case of doubt…), as the French Canadian population more readily understands it.

Item by Item Review

• Item 38: "Were you discouraged by you health problems?"

The item was originally translated as "Avez-vous été découragé(e)…" (Have you been discouraged…). After review, it was recommended to harmonize the structure of this item with the one used in items 39 and 41 respectively in order to maintain fluency in French Canadian. Thus "Have you been discouraged…" was changed to "Vous êtes-vous senti(e) découragé(e)… " (Have you felt discouraged…).

• Item 40: "Was your health a worry in your life?"

This item was originally translated as "Did your health worry you?" which is not equivalent to the original as the notion of "in your life" was not included. Following the backward translation step it was decided to reword the question to include "dans votre vie" (in your life) to maintain the original documents intent and include a notion of duration. As a result " Votre santé a-t-elle été un souci dans votre vie?" (Has your health been a worry in your life?) was adopted in French Canadian.

• Item 43: "Did you have trouble keeping attention on an activity for long"

The original expression "keeping attention" was initially translated to "se concentrer " (to concentrate). This form was determined to be too restrictive since to concentrate is an action with no notion of duration. After discussions with the French Canadian consultant following the backward translation step, it was decided to adopt "rester concentré(e) " (remain concentrated) to include the duration factor.

• Item 45: "Have others, such as family members or friends, noticed that you have trouble with your memory or problems with your concentration?"

The concept of "noticed" was initially translated as "pointed out to you". During the backward translation step it was determined that the original did not reflect the notion that the family pointed this out to the patient and was worded in such a way that the patient might have heard these things indirectly or by chance. "Faire remarquer" (to point out) refers explicitly to a verbal exchange between the patient and his/her family or friends, while "remarquer" (remark, notice) simply refers to the fact that the patient's friends or family noticed his/her problems with memory but did not necessarily mention them to the patient. It was therefore determined to replace the concept of "faire remarquer" (pointed out) with "remarqué" (noticed) following the backward translation step.

• Subtitle: "Sexual Function"

A literal translation was initially rendered but after Cognitive debriefing the translation was deemed too technical. As a result the French Canadian term "Vie Sexuelle" (Sexual life) was adopted.

• Item 49: "Ability to satisfy sexual Partner"

The French Canadian team initially suggested translating "ability" as "incapacity" given that items 46, 47, and 48 used negative wording to refer to sexual problems/dysfunctions. Item 46 refers to "lack of sexual interest", 47 to "difficulty getting or keeping an erection/inadequate lubrication, and 48 "difficulty having orgasm". Following discussion between The Project Manager and Mapi Research Institute, it was determined that use of the term "incapacité" (incapacity) would carry a distinctly negative connotation thereby discouraging the patients to rate ability even if the ability exists in a reduced form. "Incapacité" was replaced by "capacité" (capacity) to better reflect the original document and thus remain more neutral, and less influential on patient's judgment of self.

Cognitive Debriefing

The French Canadian version of the MSQOL-54 was tested on five French Canadian subjects with multiple sclerosis. The mean age of the subjects was 51 years. Completion of the questionnaire took an average of 19 minutes. (See Table 1 for the data summary.)

The subjects report on the questionnaire was favorable. It was found to be clear, relevant, and appropriate to the condition. The length of the questionnaire was acceptable to the subjects with one exception who stated that the questionnaire should not exceed its current length as problems with concentration arose during the final phase of completion.

No suggestions were made for missing articles or topics in the questionnaire.The translated MSQOL-54 went through cognitive debriefing successfully.

Conclusion

Health-related Quality of Life (HRQoL) questionnaires are increasingly used in international clinical trials. The cultural adaptation of an HRQoL questionnaire is a rigorous and complex process [31, 34]. The main objective is to obtain a conceptual equivalence between the original and translated versions, allowing, among other things, a poolingand comparison of international studies data. This incremental methodological approach has become essential as increasing amounts of data are collected about cultural differences in measuring quality of life as well as the different types of equivalence between cultures [35].

The translation of the MSQOL-54 in French Canadian was carried out within the confines of internationally accepted methodologies under the supervision of experts in the field of cultural adaptation [29, 30]. Instructions and Items 38, 43, 45 and 49 were the most debated. Problematic issues mainly resided in the field of semantics.

As suggested by Ware et al [20], HRQoL questionnaires can form a practical tool for directly linking the norms from large population surveys with the results from more focused clinical trials, outcomes research studies, and monitoring efforts in everyday clinical practice. Patients have reported that information from assessments helped guide discussions about treatment options and care planning, thereby improving communication with health care providers [36]. It has been suggested in the extent literature on doctor-patient relationships that the clinical application of HRQoL instruments helps to open the lines of communication between doctors and patients [37]. It signals to the patient that his or her doctor is prepared to discuss a wide range of health related issues thereby allowing them to relay details surrounding their condition that might otherwise remain unspoken. In addition, these discussions help patients feel understood both physically and emotionally. Of course, the use of HRQOL questionnaires can never substitute for the natural dynamics of doctor-patient communication and interaction. It can, however, be viewed as a valuable tool for structuring the information gathering process. For these reasons, the French Canadian MSQOL-54 can be considered as a useful tool to help health-care providers to conduct formal HRQoL assessments of patients with MS as a routine part of clinical practice. Its proper use will necessitate the adherence to a few basic guidelines: 1) the average time of completion should not exceed 19 minutes, 2) the questionnaire may be administered directly in the waiting room, 3) the integrity of the instruments' wording should be maintained, 4) the patient's autonomy during completion process should be respected.

The next step in the cultural adaptation process of the MSQOL-54 in French Canadian will be field research to provide the empirical data necessary for its psychometric evaluation.

References

Weinshenker BG: The natural history of Multiple Sclerosis. Neurol Clinic 1995,13(1):119–146.

Moller A, Weidemann G, Rohde U, et al.: Correlates of cognitive impairment and depressive mood disorder in multiple sclerosis. Actz Psychiatr Scand 1994, 89: 117–121.

Hauser SL: Multiple sclerosis and other demyelinating diseases. In: Harrison's principles of internal medicine (Edited by: Isselbacher KJ). McGraw Hill 1994, 2281–2294.

Sadovnick AD, Ebers GC: Epidemiology of Multiple Sclerosis: A Critical Overview. Can J Neurol Sci 1993, 20: 17–29.

Miltenburger C, Kobelt G: Quality of life and cost of multiple sclerosis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2002,104(3):272–275. 10.1016/S0303-8467(02)00051-3

Canadian Burden of Illness Study Group: Burden of Illness of Multiple Sclerosis: Part II: Quality of life. Can J Neurol Sci 1998, 25: 31–38.

Lintern TC, Beaumont JG, Kenealy PM, Murrell RC: Quality of Life (QoL) in severely disabled multiple sclerosis patients: Comparison of three QoL measures using multidimensional scaling. Qual Life Res 2001,10(4):371–378. 10.1023/A:1012219504134

Kurtzke JF: Rating neurological impairment in multiple sclerosis: An expanded disability scale status (EDSS). Neurology 1983, 33: 1444–1452.

Nortvedt MW, Riise T, Myhr KM, et al.: Quality of Life in multiple sclerosis: Measuring the disease effects more broadly. Neurology 1999,53(5):1098–1103.

Janardhan V, Bakshi R: Quality of Life and its relation to brain lesions and atrophy on magnetic resonance images in 60 patients with multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol 2000,57(10):1485–1491. 10.1001/archneur.57.10.1485

Pfennings LEMA, Cohen L, Van der Ploeg HM: Assessing the quality of life of patients with multiple sclerosis. In: Multiple sclerosis: Clinical challenges and controversies (Edited by: Thompson AJ, Polman C, Hohlfeld R). London: Martin Dunitz 1997, 195–210.

Rudick RA, Sibley W, Durelli L: Treatment of multiple sclerosis with type I interferons. In: Multiple sclerosis: Advances in clinical trial design, treatment and future perspectives (Edited by: Goodkin DE, Rudick RA). London: Springer 1996, 223–250.

Apolone G, De Carli G, Brunetti M, Garattini S: Health-related quality of life (Hr-QoL) and regulatory issues. An assessment of the European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Product-s (EMEA) recommendations on the use of Hr-QoL measures in drug approval. PharmacoEconomics 2001, 19: 187–195.

Ritvo PG, Fischer JS, Miller DM, et al.: Multiple Sclerosis Quality of life inventory: A Users Manual. New York: National Multiple Sclerosis Society 1997.

Rothwell PM, McDowell Z, Wong CK, Dorman PJ: Doctors and Patients don't agree: Cross-sectional study of patients and doctors perceptions and assessments of disability in Multiple Sclerosis. Br Med J 1997, 314: 1580–1583.

Provinciali L, Ceravolo MG, Logullo F, et al.: A multidimensional assessment of multiple sclerosis: Relationships between disability domains. Acta Neurol Scand 1999, 100: 156–162.

Miller D: Health-related quality of life assessment. In Multiple Sclerosis Therapeutics (Edited by: Rudick RA, Goodkin DE). London: Martin Dunitz Publishers 1999, 49–63.

Vickrey BG, Hays RD, Harooni R, Meyers LW: A health related quality of life measure for multiple sclerosis. Qual Life Res 1995, 4: 187–206.

Ware JE, Sherbourne CD: A 36-item short form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992, 30: 473–483.

Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinsky M, Gandek B: SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and interpretation guide. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center 1993, 10–15.

Vickrey BG, Hays RD, Genovese BJ, Myers LW, Ellison GW: Comparison of a generic to disease-targeted health-related quality-of-life measures for multiple sclerosis. J Clin Epidemiol 1997,50(5):557–569. 10.1016/S0895-4356(97)00001-2

Ford HL, Gerry E, Johnson MH, Tennant A: Health status and quality of life of people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil 23(12):516–521. 2001 Aug 15 10.1080/09638280010022090

O'Connor P, Lee L, Ng PT, Narayana P, Wolinsky JS: Determinants of overall quality of life in secondary progressive MS: A longitudinal study. Neurology 2001,57(5):889–891.

Solari A, Filippini G, Mendozzi L, Ghezzi A, Cifani S, Barbieri E, Baldini S, Salmaggi A, Mantia LL, Farinotti M, Caputo D, Mosconi P: Validation of Italian multiple sclerosis quality of life 54 questionnaire. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1999,67(2):158–62.

Leplège A, Ecosse E, Verdier A, Perneger T: The French SF-36 Health Survey: Translation, cultural adaptation and Preliminary Psychometric Evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol 1998,51(11):1013–1023. 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00093-6

Vernay D, Gerbaud L, Biolay S, Coste J, Debourse J, Aufauvre D, Beneton C, Colamarino R, Glanddier PY, Dordain G, Clavelou P: Qualité de vie et sclérose en plaques: validation de la version française de l'auto-questionnaire SEP-59. Rev Neurol 2000,156(3):247–263.

Whorf BL: A linguistic consideration of speaking in primitive communities. In: Language, thought, and reality: Selected writings of Benjamin Lee Whorf (Edited by: Carroll JB). Cambridge MA: MIT Press 1956, 65–86.

Mounin G: Les problèmes théoriques de la traduction. Paris: Gallimard 1963.

Acquadro C, Jambon B, Ellis D, Marquis P: Language and translation issues. In Quality of life and Pharmacoeconomics in clinical trials (Edited by: Spilker B). Philadelphia: Lippencourt-Raven Publishers 1996, 575–585.

Mear I: Difficulties of international clinical trials: Cultural adaptation of quality of life questionnaires. In Health-related quality of life and Patient-reported outcomes: Scientific and useful outcome criteria (Edited by: Chassany O, Caulin C). Paris: Springer Verlag Publishers 2002, 55–62.

Dauphinee SW, Gauthier L, Gandek B, Magnan L, Pierre U: Readying a US measure of health status, the SF-36, for use in Canada. Clin Invest Med 1997,20(4):224–38.

Canadian National Population Health Survey (NPHS) 1996–2002

Martel P, Vincent N, Cajolet-Laganière H: Le français québécois et la légitimité de sa description. Revue Quebecoise de Linguistique 1999,26(2):95–106.

Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D: Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: Literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol 1993, 46: 1417–1432.

Herdman M, Fox-Rushby J, Badia X: A model of equivalence in the cultural adaptation of HRQoL instruments: The universalist approach. Qual Life Res 1998, 7: 323–335.

Velikova G, Brown JM, Smith AB, Selby PJ: Computer-based quality-of-life questionnaires may contribute to doctor patient interactions in oncology. Br J Cancer 2002, 86: 51–9. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600001

Detmar SB, Aaronson NK: Quality of life assessment in daily clinical oncology practice: A feasibility study. Eur J Cancer 1998, 34: 1181–6. 10.1016/S0959-8049(98)00018-5

Acknowledgement

The authors gratefully acknowledge the grant provided for this study by Aventis Pharma Canada, and Dr Barbara Vickrey for her support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Acquadro, C., Lafortune, L. & Mear, I. Quality of life in multiple sclerosis: translation in French Canadian of the MSQoL-54. Health Qual Life Outcomes 1, 70 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-1-70

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-1-70