Abstract

Background

Smoking cessation has important immediate health benefits. The comparative short-term effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions is not well known. We aimed to determine the relative effectiveness of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), bupropion and varenicline at 4 weeks post-target quit date.

Methods

We searched 10 electronic medical databases (inception to October 2008). We selected randomized clinical trials [RCTs] evaluating interventions for our primary outcome of abstinence from smoking at at-least 4 weeks post-target quit date, with biochemical confirmation. We conducted random-effects odds ratio (OR) meta-analysis and meta-regression. We compared treatment effects across interventions using head-to-head trials and calculated indirect comparisons.

Results

We combined a total of 101 trials evaluating delivery of NRT versus inert controls at approximately 4 weeks post-target quit date (total n = 31,321). The pooled overall OR is OR 2.05 (95% Confidence Interval [CI], 1.89-2.23, P =< 0.0001). We pooled data from 31 bupropion trials contributing a total n of 11,118 participants and found a pooled OR of 2.25 (95% CI, 1.94-2.62, P =< 0.0001). We evaluated 9 varenicline trials compared to placebo. Our pooled estimate for cessation at 4 weeks post-target quit date found a pooled OR of 3.16 (95% CI, 2.55-3.91, P =< 0.0001). Two trials evaluated head to head comparisons of varenicline and bupropion and found a pooled estimate of OR 1.86 (95% CI, 1.49-2.33, P =< 0.0001 at 4 weeks post-target quit date. Indirect comparisons were: NRT and bupropion, OR, 1.09, 95% CI, 0.93-1.31, P = 0.28; varenicline and NRT, OR 1.56, 95% CI, 1.23-1.96, P = 0.0002; and, varenicline and bupropion, OR 1.40, 95% CI, 1.08-1.85, P = 0.01.

Conclusion

Pharmacotherapeutic interventions are effective for increasing smoking abstinence rates in the short-term.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Smoking remains the leading cause of preventable death in the world.[1] Smoking cessation is associated with important benefits at the individual and societal levels. Given the prevalence of smoking, considerable efforts have been directed toward developing interventions to assist smokers in quitting. However, smoking cessation interventions have had heterogeneous successes.[2] Smoking cessation is necessary to reduce future morbidity and mortality, however many patients have difficulty discontinuing.

Both psychosocial and pharmaceutical interventions have been evaluated for their success in achieving smoking discontinuation.[3, 4] Drug therapies are now licensed in North America and Europe to promote smoking cessation. The most commonly evaluated of these has been nicotine replacement therapy [NRT].[5, 6] More recently, attention has focused on the use of anti-depressant therapy and specifically the agent bupropion[7]. A new intervention approved in 2006, varenicline, targets nicotine receptors to reduce craving and pleasure sensations. Recent guidelines and evaluations call for combining therapies to provide optimal patient management.[3, 8]

We,.[9] and others,. [10–13] have previously reported on the efficacy of these interventions for longer-term cessation (3-12 months) durations. No systematic review has yet evaluated short-term quit rates from available therapies. Guidelines for smoking cessation programmes consider quitting 4-weeks post-planned quit date as a successful short-term cessation.[14] Short-term smoking abstinence is especially important in patients requiring immediate behaviour changes, such as those with recent cardiovascular events.[15] or undergoing surgery.[16] We conducted a meta-analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials [RCTs] to identify the effectiveness of the various pharmacological interventions in improving abstinence rates at 4-weeks and 6 months.

Methods

Eligibility Criteria

Our primary outcome of interest was smoking abstinence at approximately 4 weeks post-target quit date (TQD). Our secondary outcomes were short-term smoking abstinence defined as 6 months after initiating treatment or closest available data to that time point, within one month. We included any RCT of NRT of any delivery method, bupropion or varenicline. We included only RCTs of at least 4 weeks duration with biochemical confirmation of smoking abstinence because of the likelihood of abstinence over-reporting. While methods of assessing smoking abstinence vary from study to study, the most common method is self-report. However, this can have false cessation rates as high as 30%.[17]False reporting is most likely to occur in a trial setting or in assessing smoking status after a medical event. Laboratory tests are often used to verify smoking status, especially in clinical trials. Methods of biological verification include serum and saliva thiocyanate (SCN), expired carbon monoxide (CO), plasma, saliva and urinary cotinine and plasma and urinary nicotine. Each of these have various strengths and weaknesses.[18] Studies had to report smoking abstinence as either sustained abstinence at the time periods or point-prevalence of abstinence. When both outcomes were available, we considered sustained abstinence to be a superior clinical marker of abstinence. We excluded dose ranging studies, non-RCTs, post-hoc analyses, maintenance therapy, and studies that reported outcomes as self-report.

Study endpoints

Our primary endpoint was the 4-week post-TQD. This is variably reported in studies over years of publications. National committees require data on the 4-week post-TQD and each group of trials of intervention deals with this endpoint differently. Newer studies typically report this as the last 4-weeks of treatment as pharmacotherapy is begun prior to TQD. Where this specific endpoint is reported, we extracted data on 4-week post-TQD. Where not reported, we extracted data on 4 weeks post-intervention. Our secondary endpoint, 6-months post intervention is typically reported as 6 months post-treatment, but may also be reported as 6 months post TQD. Where reported specifically, we extracted data on 6-month post-TQD.

Search strategy

In consultation with a medical librarian (PR), we established a search strategy. We searched independently, in duplicate, the following 10 databases (from inception to October 1, 2008): MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane CENTRAL, AMED, CINAHL, TOXNET, Development and Reproductive Toxicology, Hazardous Substances Databank, Psych-info and Web of Science, databases that included the full text of journals (OVID, ScienceDirect, and Ingenta, including articles in full text from approximately 1700 journals since 1993). In addition, we searched the bibliographies of published systematic reviews.[5, 19–25, 7, 10, 11, 13, 26] and health technology assessments.[27] Searches were not limited by language, sex or age.

Study selection

Two investigators (EM, PW) working independently, in duplicate, scanned all abstracts and obtained the full text reports of records, that indicated or suggested that the study was a RCT evaluating a smoking abstinence therapy on the outcomes of interest. After obtaining full reports of the candidate trials (either in full peer-reviewed publication or press article) the same reviewers independently assessed eligibility from full text papers.

Data collection

Two reviewers (PW, EM) conducted data extraction independently using a standardized pre-piloted form. Reviewers collected information about the smoking intervention tested, the population studied (age, sex, underlying conditions), treatment dosages and dosing schedules, the treatment effect at 4 weeks post-TQD and at 6 months post-intervention, the specific measurement of abstinence (sustained or point-prevalence), and the chemical confirmation methods. Study evaluation included general methodological quality features including allocation concealment, sequence generation, blinding status, intention-to-treat, and appropriate descriptions of loss to follow-up. We entered the data into an electronic database such that duplicate entries existed for each study; when the two entries did not match, we resolved differences through discussion and consensus.

Data analysis

In order to assess inter-rater reliability on inclusion of articles, we calculated the Phi statistic, which provides a measure of inter-observer agreement independent of chance.[28] We calculated the Odds Ratios [OR] and appropriate 95% Confidence Intervals [CIs] of outcomes according to the number of events of abstinence reported in the original studies or sub-studies. Odds Ratios are the preferred effect measure in smoking cessation trials. In circumstances of zero outcome events in one arm of a trial, we added 1 to each arm, as suggested by Sheehe.[29] We first pooled studies of all NRT interventions versus all controls using the DerSimonian-Laird random effects method,.[30] which recognizes and anchors studies as a sample of all potential studies, and incorporates an additional between-study component to the estimate of variability.[31] We calculated the I2 statistic for each analysis as a measure of the proportion of the overall variation that is attributable to between-study heterogeneity.[32] Forest plots are displayed for each primary analysis, showing individual study effect measures with 95% CIs, and the overall DerSimmonian-Laird pooled estimate. We then conducted a meta-regression analysis on the NRT studies with predictors of heterogeneity including the following covariates: placebo control; reporting of sequence generation; reporting of allocation concealment; use of gum or patch; and, method of chemical confirmation of abstinence. We additionally conducted separate pooled analyses of NRT versus placebo, gum versus control and patch versus control. We conducted all analyses at 4 weeks and also at 6 months post-TQD. For bupropion trials, we pooled all bupropion trials versus all controls and conducted a meta-regression analysis using the following covariates: placebo control; reporting of sequence generation; reporting of allocation concealment; method of chemical confirmation of abstinence; and plans to quit. We conducted separate meta-regression analyses and calculated the relevant ORs for the covariates as the exponent of the coefficient.[33] We additionally pooled all placebo-controlled trials and evaluated effect sizes at 4 weeks and at 6 months post-TQD. For head-to-head trials of bupropion versus NRT, we conducted pooled random-effects analyses at 4 weeks and at 6 months post-TQD. For varenicline trials, we conducted pooled random-effects analyses of varenicline versus placebo and for head-to-head trials of varenicline versus bupropion or NRT at 4 weeks year and at 6 months. post-TQD. Head-to-head trials provide the strongest inferences regarding intervention superiority.[34] However, with so few head-to-head trials of varenicline versus NRT, we conducted indirect comparisons of these interventions versus placebo using methods described by Bucher et al.[35] This method maintains the randomization from each trial and compares the summary estimates of pooled interventions with CIs. Analyses were conducted using StatsDirect (version 2.5.2, http://www.statsdirect.com) and Comprehensive Meta-analysis (version 2, http://www.meta-analysis.com).

Results

Study inclusion

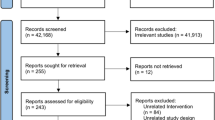

We identified 795 abstracts from our extensive searches. We excluded 532 as irrelevant to meeting our inclusion criteria. We obtained 263 full-text studies for screening. We further excluded 94 studies for reasons explained in figure 1 [See Additional File 1]. In total, we included data from 168 RCTs. Agreement was near perfect (φ => 0.9).

Methods reporting

Nicotine Replacement Therapy

One hundred and fifteen RCTs of NRT provided either safety or efficacy data at approximately 4 weeks post-TQD. [36–150]. Eighty-two (82/115) used a placebo control [36–116, 150]. Trials were variably reported with only 43 reporting methods of sequence generation[37, 39, 41, 46, 52, 55, 57, 70, 73–76, 80, 83, 85–92, 95–98, 103, 105, 110–112, 114–116, 118, 121, 125, 126, 139, 142, 144, 145, 148]. Eighteen (18/115) reported on allocation concealment. [37, 39, 41, 46, 70, 76, 81, 84, 86, 88–90, 95, 105, 111, 112, 126, 148], 81 (81/115) reported on who was blinded[36–73, 75–78, 120, 131, 132, 79–94, 96–98, 149, 100–103, 105–116]. Most trials used some form of chemical confirmation of abstinence, with carbon monoxide being the most common (104/115).[36–38, 40–57, 59–71, 73, 117–120, 122–124, 129–134].[72, 74–81, 83–94, 97–99, 135, 137–140, 149, 100–111, 113–116, 141–148], salivary cotinine (26/115).[42, 45, 46, 50, 56, 66, 68, 75, 76, 79, 83, 93, 95, 103, 106, 111, 123, 125, 128, 129, 132–134, 145, 147, 150], serum status (7/115).[39, 43, 58, 71, 114, 119, 136], or urine sampling (4/115)[74, 112, 126, 129]. Most (94/115) reported that participants were trying to quit smoking.[36–39, 41, 44–52, 54–65, 117, 118, 121, 122, 124–129, 131, 132, 68–75, 77, 78, 80–82, 85–87, 89–91, 93, 94, 97–100, 102–106, 108, 110–116, 136–140, 143–149].

Bupropion

Forty-two bupropion trials met our inclusion criteria.[113, 114, 142, 143, 149, 151–187] and reported on outcomes at 4 weeks post-TQD. Almost all trials (40/42) used a placebo control.[113, 114, 149, 151–187], with 2 providing education.[143] and counseling.[142] as controls. The quality of reporting studies varied considerably. We found that important study quality indicators were reported sporadically. Sequence generation was reported in 23 of 42 trials.[113, 114, 142, 152–154, 157–159, 161–164, 169–173, 176, 180, 182, 185, 186], allocation concealment was reported in 12 of 42 trials.[152, 153, 157–159, 162–164, 170, 176, 182, 186], the status of who was blinded was reported in 38 of 42 trials.[113, 114, 142, 149, 151–174, 176, 177, 180–187], 37 trials.[113, 114, 142, 143, 149, 151–155, 157–165, 167–172, 174–177, 180–187] confirmed cessation using carbon monoxide testing, while 13 used urinary cotinine[114, 152, 153, 157–159, 166, 173, 174, 178–180, 184]. Almost all trials used participants that were planning to quit smoking (38/42).[113, 114, 142, 143, 149, 151–161, 163, 165–171, 173–180, 182–187].

Varenicline

Eleven varenicline studies met our inclusion criteria[162–164, 188–195]. One reported only on safety[193]. All trials had a placebo control, 3 also had a bupropion control in their 3 armed trials[163, 164, 188]. We found that almost all (7/11) provided an additional intervention of counseling available[162–164, 190–192, 194]. Sequence generation was reported in 6 of 11 studies.[162–164, 189, 192, 195], allocation concealment in 7 of 11 studies.[162–164, 189, 192, 194, 195], blinding status in all studies (11/11), and the use of carbon monoxide testing in 10 of 11 studies.[162–164, 188–192, 194, 195], and urinary cotinine in 1 of 11 studies[193]. Five trials reported that the participants were trying to stop smoking[163, 189, 190, 192, 195].

Effectiveness

Nicotine Replacement Therapy

We combined a total of 101 trials.[36–43, 45–47, 49–52, 54–65, 117–119, 121, 123, 128–132, 147].[66–69, 71, 73–82, 84, 86–90, 134, 135, 137, 138, 149, 91, 94, 95, 97–100, 103, 105, 106, 111, 114–116, 139–146]evaluating some delivery form of NRT versus inert controls at approximately 4 weeks post-TQD (total n = 31,321). The pooled overall OR is OR 2.05 (95% CI, 1.89-2.23, P =< 0.0001, I2 = 51.8%, 95% CI = 38% to 61.3%, P =< 0.0001, See Figure 2). This assessment permitted a sufficient number of studies to assess publication bias and we found marginal evidence of it (Egger's P = 0.055, See Figure 3). We evaluated whether reporting exactly 4 week post-TQD data influenced outcomes and found trials reporting exactly 4 week post-TQD data were more likely to report treatment effects (OR 2.11, 95% CI, 1.97-2.27, P =< 0.0001). These pooled trials yielded an OR 1.82, 95% CI, 1.62-2.05, P =< 0.0001, I2 = 41.6%, 95% CI, 9.1 to 59.1%, P = 0.002). Trials reporting on sustained abstinence at approximately 4 weeks post-TQD yielded a similar pooled estimate (38 RCTs.[45, 52, 54, 56, 57, 60, 61, 66, 67, 69, 73, 75, 81, 82, 86, 87, 89, 91, 94, 98, 99, 103, 116, 124, 129, 131, 139, 142, 145, 149], n = 17,606, OR 2.24, 95% CI, 1.94-2.28, P =< 0.0001, I2 = 67.7%, 95% CI = 53.7% to 76.1%, P =< 0.0001). When we evaluated trials assessing NRT only to placebo we pooled 74 trials.[36–43, 45–47, 49–52, 54–69, 71, 73–82, 131, 84, 86–91, 94, 95, 97, 98, 100, 103, 105, 106, 111, 114–116, 149] (total n = 25,154: 24,654) and found a pooled estimate of 2.13 (95% CI, 1.94-2.34, P =< 0.0001, I2 = 53.6%, 95% CI = 37.6% to 64%, P =< 0.0001, this was not dissimilar when evaluating sustained abstinence (29 RCTs.[45, 52, 54, 56, 57, 60, 61, 66, 67, 69, 73, 75, 81, 82, 86, 87, 89, 91, 94, 98, 99, 103, 124, 131, 149], n = 14,306, OR 2.36 (95% CI, 2.04-2.73 I2 = 61.4%, 95% CI = 37.5% to 73.5%, P =< 0.0001).

When we specifically looked at the effectiveness of NRT gum versus all inert controls we pooled data from 41 trials.[36–42, 45–47, 50, 67, 74, 78, 106, 111, 114, 117–119, 121, 123, 124, 128–132, 134, 137, 138, 141, 144, 146] (n = 9,460) and found an OR of 1.76 (95% CI, 1.54-2.01, P =< 0.0001, I2 = 38.9% (95% CI = 3.8% to 57.6%, P = 0.004). This was not dissimilar from gum versus placebo controls (23 trials.[36–42, 45–47, 50, 67, 74, 78, 106, 111, 114, 124, 131], n = 5818, OR 1.66, 95% CI, 1.41-1.96, P =< 0.0001, I2 = 41.1% P = 95% CI = 0% to 63.2%, P = 0.01). When we specifically examined trials assessing the effectiveness of NRT cutaneous patches versus inert controls we included data from 47 RCTs.[49, 51, 52, 54, 56, 58–60, 62–66, 69, 71, 73, 77, 79, 82, 84, 86, 87, 89–91, 95, 97, 100, 103, 105, 106, 115, 135, 139, 141–145, 149] (n = 15,980) and found a pooled estimate of 2.11 (95% CI, 1.85-2.40, P =< 0.0001, I2 = 54.8%, 95% CI, 34.7 to 66.7%, P =< 0.0001). This was not different when examining NRT patches versus placebo controls (38 trials [49, 51, 52, 54, 56, 58–60, 62–66, 69, 71, 73, 77, 79, 82, 84, 86, 87, 89–91, 95, 97, 100, 103, 105, 106, 115, 149], n = 14,988, OR 2.15, 95% CI, 1.86-2.48, P =< 0.0001, I2 = 59.5%, 95% CI = 39.3 to 70.8%, P =< 0.0001).

When evaluating NRT versus controls at 6 months (96 RCTs, n = 30,422) we found a pooled estimate of OR 1.92 (95% CI, 1.73-2.14, P =< 0.0001, I2 = 64.2%, 95% CI, 54.8 to 70.8%, P =< 0.0001). This was not dissimilar when evaluating NRT as either gum (23 RCTs, n = 5818, OR 1.69, 95% CI, 1.37-2.08, P =< 0.0001, I2 = 55.9%, 95% CI, 21.8 to 71.3%, P = 0.0004) or cutaneous patch (43 RCTs, n = 16,298, OR, 1.90, 95% CI, 1.62-2.33, I2 = 62.4%, 95% CI, 45.5 to 72.3%, P =< 0.0001).

Bupropion

We pooled data from 31 trials.[114, 142, 143, 149, 152–157, 162–173, 175–177, 182–187] contributing a total n of 11,118 participants providing data at approximately 4 weeks post-TQD and found a pooled OR of 2.25 (95% CI, 1.94-2.62, P =< 0.0001, I2 = 78, 95% CI, 70-83%, P =< 0.001, See Figure 4). When we evaluated studies assessing sustained cessation (25 randomized cohorts.[142, 149, 151, 152, 154, 155, 159, 160, 162–166, 168, 170, 171, 175, 176, 180, 182, 185, 187], n = 8,724) we found a pooled OR of 1.96, 95% CI, 1.39-2.79, P = 0.0002, I2 = 89%, 95% CI, 86-92%, P =< 0.0001, See Figure 5). We were able to explain the large heterogeneity in the analysis through meta-regression as studies failing to report allocation concealment were associated with increased effect sizes (OR 2.29, 95% CI, 2.05-2.60, P =< 0.0001), as were studies confirming abstinence through urinary cotinine (OR 2.44, 95% CI, 2.18-2.66, P =< 0.0001), but not those utilizing carbon monoxide confirmation (OR 1.30, 95% CI, 0.87-1.95, P = 0.18).

Our secondary outcomes for effectiveness also indicated significant benefits with bupropion over controls at 6 months (OR 1.75, 95% CI, 1.54-1.97, P =< 0.0001, I2 = 32%, 95% CI, 0-53%, P =< 0.0001). This effect was consistent when applying only continuous abstinence in the 6 month period (OR 1.94, 95% CI, 1.62-2.32, P =< 0.0001, I2 = 34, 95% CI, 0-62, P = 0.04).

Varenicline

When we evaluated varenicline for smoking abstinence at approximately the last 4 weeks of treatment (4 weeks post-TQD) compared to placebo, we pooled 9 trials.[162–164, 189–192, 194, 196] contributing a total n of 5,192 participants. Our pooled estimate for abstinence at 4 weeks post-TQD found a pooled OR of 3.16 (95% CI, 2.55-3.91, P =< 0.0001, I2 = 53%, 95% CI, 0-76%, P = 0.02, See Figure 6). We were able to explain the heterogeneity in the analysis through meta-regression as studies failing to report allocation concealment were associated with increased effect sizes (OR 3.35, 95% CI, 2.45-4.57, P =< 0.0001). Our 6 month evaluations of varenicline versus placebo yielded similar estimates for continuous abstinence in the 6 month period (OR 2.17, 1.48-3.19, P =< 0.0001, I2 = 80, 95% CI, 49-90%, P =< 0.0001).

Two trials evaluated head to head comparison of varenicline and bupropion and found a pooled estimate of OR 1.86 (95% CI, 1.49-2.33, P =< 0.0001) using continuous abstinence rates at 4 weeks and, at 6 months post-TQD (OR 1.64, 95% CI, 1.28-2.10, P =< 0.0001).[163, 164] One trial evaluated varenicline versus NRT patch (n = 757) for continuous abstinence at the last 4 weeks post-TQD using carbon monoxide confirmation (OR 1.70, 95% CI, 1.26-2.28, P =< 0.001).[188] This same trial reported on continuous abstinence at 6 months (24 weeks), but the difference was not significant (OR 1.29, 95% CI, 0.94-1.77, P = 0.11).

Adjusted indirect comparison (Figure 7)

We applied an adjusted indirect comparison evaluating NRT, bupropion and varenicline on our primary endpoint of 4 weeks post-TQD abstinence. We were unable to display a significant difference between NRT and bupropion at 4-weeks (OR, 1.09, 95% CI, 0.93-1.31, P = 0.28). Varenicline was superior to both NRT (OR 1.56, 95% CI, 1.23-1.96, P = 0.0002) and bupropion at post-TQD (OR 1.40, 95% CI, 1.08-1.85, P = 0.01).

Discussion

This study confirms the short-term effectiveness of all three smoking interventions compared to placebo. Our findings stand in line with outcomes evaluated over a longer period, up to one year, of these same interventions.[9, 10] This finding should be of interest to clinicians, policy-makers and patients. As interventions to assist in smoking cessation are increasingly available, the combination of these interventions, along with socio-behavioural interventions, should be a research priority.[8]

The definition of smoking abstinence and relapse are variable across studies. The most common time periods of smoking cessation required to be considered abstinent are 24 hours, 7 days and 30 days. Relapse is defined by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute as having smoked at least a puff for 7 days after having quit. Seventy five to 80 percent of smokers relapse within the first 6 months. Relapse rates continue to remain high from 6 to 12 months (7 to 35% of those abstinent at 6 months). Relapse occurs at a lower rate following one year of cessation.[4] The National Center for Health Education Code of Practice and Standards for the Evaluation of Group Smoking Cessation Programs recommends at least one year of follow-up before determining if patients have quit smoking.[4] The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (UK) Guidelines require the reporting of short-term abstinence rates. Further, immediate abstinence of smoking following a major cardiovascular event has major benefits in preventing secondary events.[197] We recognize that multiple short-term abstinence attempts followed by relapses may be associated with long term smoking use, an issue that is increasingly complex to manage from a clinical and public health perspective.[198] However, our findings are consistent with the longer term evaluations and indicate that sustained abstinence is possible in the clinical trial setting. Furthermore there are some physiological and health advantages to short-term abstinence. For example, individuals with cardiovascular events can immediately benefit from smoking discontinuation because of improvements in several physiological variables including reduced myocardial oxygen demand, improved myocardial oxygen supply, reduced activation of the sympathetic system, reduced risk of arrhythmias and reduced acute thrombosis risk. These benefits could be particularly critical in the peri-event period when patients are at increased risk of complications or repeat events. Thus even if relapse occurs at a later stage, abstinence around the time of an event could prove beneficial.

When we previously evaluated varenicline to NRT and bupropion, we had data from only 4 trials.[9] This evaluation found that the addition of 7 trials continues to demonstrate elevated varenicline effects compared to NRT and bupropion. Further community effectiveness interventions will be required to ensure generalizability.

There are several strengths and limitations to consider when interpreting our analysis. Strengths of this review include the comprehensive search strategy that improved the likelihood of identifying all relevant studies. Duplicate extraction of data reduced the potential for bias in this component of the synthesis process. By limiting this review to randomized trials we ensured that the included studies would have reduced likelihood of systematic error and therefore have high internal validity. Our use of meta-regression to identify sources of heterogeneity in the meta-analyses is a strength and demonstrated that several of the a priori chosen covariates were predictors of heterogeneity. To reduce patient-reporting bias, we included only studies that chemically confirmed the cessation of smoking at the specific time-points- this has been a weakness in previous reviews.[23]

Limitations of this meta-analysis include the potential for publication bias, in particular the possibility that small negative studies would not be published. Publication bias on short-term effects is likely due to both author-initiated bias and journal-initiated bias against short-term evaluations. We included only published trials so it is possible that other trials have been conducted and never published. However, it is unlikely that the presence of these studies would have altered the findings of our analysis given the large number of studies included and the consistency with the longer-term evaluations (both 6 months and one year).[9, 10] We limited our search to English language databases (although we would include non-English articles if identified) so the possibility of quality studies in other languages does exist. We used both direct and indirect comparisons to evaluate the relative effectiveness of agents. Head-to-head trials provide the strongest inferences regarding intervention superiority.[34] In the presence of existing head-to-head trials of varenicline versus NRT.[188] and bupropion,.[163, 164] it is arguable whether indirect comparisons are required.[199] In this case, the results were consistent. We used the indirect comparison method proposed by Bucher et al., that respects the principle of randomization between trials.[200] Other strategies we have previously applied,.[201] including mixed treatment comparisons, offer similar benefits.[199]

Conclusion

In conclusion, our review demonstrates clear efficacy of smoking cessation pharmacotherapies in the short term and provides similar estimates of efficacy as longer term evaluations.[9, 10] Given the benefits of smoking abstinence in both primary and secondary prevention of major morbidities, the use of these therapies in patients with active smoking related disease warrants further study.[15] Future research to evaluate the efficacy and safety of these interventions in combination and in patients with advanced diseases is warranted.

Funding

This study received unrestricted funding from Pfizer Ltd to evaluate anti-smoking agents. They had no role in the conduct, interpretation or writing of this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- CO:

-

Carbon monoxide

- NRT:

-

Nicotine replacement therapy

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- RCT:

-

Randomized Clinical Trial

- SCN:

-

Saliva thiocynate

- 95% CI:

-

95% Confidence intervals.

References

Peto R, Lopez AD, Boreham J, Thun M, Heath C, Doll R: Mortality from smoking worldwide. Br Med Bull. 1996, 52: 12-21.

Law M, Tang JL: An analysis of the effectiveness of interventions intended to help people stop smoking. Arch Intern Med. 1995, 155: 1933-1941. 10.1001/archinte.155.18.1933.

Kuehn BM: Updated US smoking cessation guideline advises counseling, combing therapies. JAMA. 2008, 299: 2736-10.1001/jama.299.23.2736.

US Public Health Service. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. 2008, [http://www.ahrq.gov/path/tobacco.htm]

Silagy C, Lancaster T, Stead L, Mant D, Fowler G: Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004, CD000146-

Salanti G, Kavvoura FK, Ioannidis JP: Exploring the geometry of treatment networks. Ann Intern Med. 2008, 148: 544-553.

Hughes J, Stead L, Lancaster T: Antidepressants for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004, CD000031-

Shah SD, Wilken LA, Winkler SR, Lin SJ: Systematic review and meta-analysis of combination therapy for smoking cessation. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2008, 48: 659-665. 10.1331/JAPhA.2008.07063.

Wu P, Wilson K, Dimoulas P, Mills EJ: Effectiveness of smoking cessation therapies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2006, 6: 300-10.1186/1471-2458-6-300.

Eisenberg MJ, Filion KB, Yavin D, Belisle P, Mottillo S, Joseph L, Gervais A, O'Loughlin J, Paradis G, Rinfret S, Pilote L: Pharmacotherapies for smoking cessation: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Cmaj. 2008, 179: 135-144.

Cahill K, Stead LF, Lancaster T: Nicotine receptor partial agonists for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008, CD006103-

Stead LF, Perera R, Bullen C, Mant D, Lancaster T: Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008, CD000146-

Hughes JR, Stead LF, Lancaster T: Antidepressants for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007, CD000031-

NICE: NICE: smoking cessation guidance. 2008, [http://www.idea.gov.uk/idk/core/pagedo?pageId=8024618]

Wilson K, Gibson N, Willan A, Cook D: Effect of smoking cessation on mortality after myocardial infarction: meta-analysis of cohort studies. Arch Intern Med. 2000, 160: 939-944. 10.1001/archinte.160.7.939.

Thomsen T, Tonnesen H, Moller AM: Effect of preoperative smoking cessation interventions on postoperative complications and smoking cessation. The British journal of surgery. 2009, 96: 451-461. 10.1002/bjs.6591.

Ruth KJ, Neaton JD: Evaluation of two biological markers of tobacco exposure. MRFIT Research Group. Prev Med. 1991, 20: 574-589. 10.1016/0091-7435(91)90056-A.

Hounton SH, Carabin H, Henderson NJ. Towards an understanding of barriers to condom use in rural Benin using the Health Belief Model: a cross sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2005, 5: 8-10.1186/1471-2458-5-8.

Lancaster T, Silagy C, Fowler G: Training health professionals in smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000, CD000214-

Silagy C: Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000, CD000165-

Silagy C, Lancaster T, Stead L, Mant D, Fowler G: Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001, CD000146-

Silagy C, Lancaster T, Stead L, Mant D, Fowler G: Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002, CD000146-

Silagy C, Mant D, Fowler G, Lancaster T: Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000, CD000146-

Silagy C, Mant D, Fowler G, Lancaster T: Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000, CD000146-

Stead LF, Lancaster T, Silagy CA: Updating a systematic review--what difference did it make? Case study of nicotine replacement therapy. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2001, 1: 10-10.1186/1471-2288-1-10.

Hughes JR, Stead LF, Lancaster T: Antidepressants for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002, CD000031-

NICE: TA39 Smoking cessation - bupropion and nicotine replacement therapy: Guidance. Issue Date: March 2002 Review Date: March 2005. [http://www.nice.org.uk/TA039]

Meade MO, Guyatt GH, Cook RJ, Groll R, Kachura JR, Wigg M, Cook DJ, Slutsky AS, Stewart TE: Agreement between alternative classifications of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001, 163: 490-493.

Sheehe PR: Combination of log relative risk in retrospective studies of disease. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1966, 56: 1745-1750.

Fleiss JL: The statistical basis of meta-analysis. Stat Methods Med Res. 1993, 2: 121-145. 10.1177/096228029300200202.

DerSimonian R, Laird N: Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986, 7: 177-188. 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG: Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002, 21: 1539-1558. 10.1002/sim.1186.

Thompson SG, Higgins JP: How should meta-regression analyses be undertaken and interpreted?. Stat Med. 2002, 21: 1559-1573. 10.1002/sim.1187.

McAlister FA, Laupacis A, Wells GA, Sackett DL: Users' Guides to the Medical Literature: XIX. Applying clinical trial results B. Guidelines for determining whether a drug is exerting (more than) a class effect. Jama. 1999, 282: 1371-1377. 10.1001/jama.282.14.1371.

Bucher HC, Griffith LE, Guyatt GH: Systematic review on the risk and benefit of different cholesterol-lowering interventions. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999, 19: 187-195.

Jarvis MJ, Raw M, Russell MA, Feyerabend C: Randomised controlled trial of nicotine chewing-gum. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1982, 285: 537-540. 10.1136/bmj.285.6341.537.

Fagerstrom KO: A comparison of psychological and pharmacological treatment in smoking cessation. J Behav Med. 1982, 5: 343-351. 10.1007/BF00846161.

Malcolm RE, Sillett RW, Turner JA, Ball KP: The use of nicotine chewing gum as an aid to stopping smoking. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1980, 70: 295-296. 10.1007/BF00427889.

Comparison of four methods of smoking withdrawal in patients with smoking related diseases. Report by a subcommittee of the Research Committee of the British Thoracic Society. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983, 286: 595-597. 10.1136/bmj.286.6365.595.

Schneider NG, Jarvik ME, Forsythe AB, Read LL, Elliott ML, Schweiger A: Nicotine gum in smoking cessation: a placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Addict Behav. 1983, 8: 253-261. 10.1016/0306-4603(83)90020-5.

Jamrozik K, Fowler G, Vessey M, Wald N: Placebo controlled trial of nicotine chewing gum in general practice. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1984, 289: 794-797. 10.1136/bmj.289.6448.794.

Hall SM, Tunstall CD, Ginsberg D, Benowitz NL, Jones RT: Nicotine gum and behavioral treatment: a placebo controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1987, 55: 603-605. 10.1037/0022-006X.55.4.603.

Tonnesen P, Fryd V, Hansen M, Helsted J, Gunnersen AB, Forchammer H, Stockner M: Two and four mg nicotine chewing gum and group counselling in smoking cessation: an open, randomized, controlled trial with a 22 month follow-up. Addict Behav. 1988, 13: 17-27. 10.1016/0306-4603(88)90021-4.

Areechon W, Punnotok J: Smoking cessation through the use of nicotine chewing gum: a double-blind trial in Thailand. Clin Ther. 1988, 10: 183-186.

Fortmann SP, Killen JD, Telch MJ, Newman B: Minimal contact treatment for smoking cessation. A placebo controlled trial of nicotine polacrilex and self-directed relapse prevention: initial results of the Stanford Stop Smoking Project. Jama. 1988, 260: 1575-1580. 10.1001/jama.260.11.1575.

Hughes JR, Gust SW, Keenan RM, Fenwick JW, Healey ML: Nicotine vs placebo gum in general medical practice. Jama. 1989, 261: 1300-1305. 10.1001/jama.261.9.1300.

Blondal T: Controlled trial of nicotine polacrilex gum with supportive measures. Arch Intern Med. 1989, 149: 1818-1821. 10.1001/archinte.149.8.1818.

Gross J, Stitzer ML, Maldonado J: Nicotine replacement: effects of postcessation weight gain. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989, 57: 87-92. 10.1037/0022-006X.57.1.87.

Abelin T, Ehrsam R, Buhler-Reichert A, Imhof PR, Muller P, Thommen A, Vesanen K: Effectiveness of a transdermal nicotine system in smoking cessation studies. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 1989, 11: 205-214.

Killen JD, Fortmann SP, Newman B, Varady A: Evaluation of a treatment approach combining nicotine gum with self-guided behavioral treatments for smoking relapse prevention. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1990, 58: 85-92. 10.1037/0022-006X.58.1.85.

Hurt RD, Lauger GG, Offord KP, Kottke TE, Dale LC: Nicotine-replacement therapy with use of a transdermal nicotine patch--a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Mayo Clin Proc. 1990, 65: 1529-1537.

Tonnesen P, Norregaard J, Simonsen K, Sawe U: A double-blind trial of a 16-hour transdermal nicotine patch in smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 1991, 325: 311-315.

Campbell IA, Prescott RJ, Tjeder-Burton SM: Smoking cessation in hospital patients given repeated advice plus nicotine or placebo chewing gum. Respir Med. 1991, 85: 155-157. 10.1016/S0954-6111(06)80295-7.

Daughton DM, Heatley SA, Prendergast JJ, Causey D, Knowles M, Rolf CN, Cheney RA, Hatlelid K, Thompson AB, Rennard SI: Effect of transdermal nicotine delivery as an adjunct to low-intervention smoking cessation therapy. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Arch Intern Med. 1991, 151: 749-752. 10.1001/archinte.151.4.749.

Sutherland G, Stapleton JA, Russell MA, Jarvis MJ, Hajek P, Belcher M, Feyerabend C: Randomised controlled trial of nasal nicotine spray in smoking cessation. Lancet. 1992, 340: 324-329. 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91403-U.

Sachs DP, Sawe U, Leischow SJ: Effectiveness of a 16-hour transdermal nicotine patch in a medical practice setting, without intensive group counseling. Arch Intern Med. 1993, 153: 1881-1890. 10.1001/archinte.153.16.1881.

Tonnesen P, Norregaard J, Mikkelsen K, Jorgensen S, Nilsson F: A double-blind trial of a nicotine inhaler for smoking cessation. Jama. 1993, 269: 1268-1271. 10.1001/jama.269.10.1268.

Merz PG, Keller-Stanislawski B, Huber T, Woodcock BG, Rietbrock N: Transdermal nicotine in smoking cessation and involvement of non-specific influences. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol. 1993, 31: 476-482.

Russell MA, Stapleton JA, Feyerabend C, Wiseman SM, Gustavsson G, Sawe U, Connor P: Targeting heavy smokers in general practice: randomised controlled trial of transdermal nicotine patches. Bmj. 1993, 306: 1308-1312. 10.1136/bmj.306.6888.1308.

Westman EC, Levin ED, Rose JE: The nicotine patch in smoking cessation. A randomized trial with telephone counseling. Arch Intern Med. 1993, 153: 1917-1923. 10.1001/archinte.153.16.1917.

Hjalmarson A, Franzon M, Westin A, Wiklund O: Effect of nicotine nasal spray on smoking cessation. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Arch Intern Med. 1994, 154: 2567-2572. 10.1001/archinte.154.22.2567.

Hurt RD, Dale LC, Fredrickson PA, Caldwell CC, Lee GA, Offord KP, Lauger GG, Marusic Z, Neese LW, Lundberg TG: Nicotine patch therapy for smoking cessation combined with physician advice and nurse follow-up. One-year outcome and percentage of nicotine replacement. Jama. 1994, 271: 595-600. 10.1001/jama.271.8.595.

Fiore MC, Kenford SL, Jorenby DE, Wetter DW, Smith SS, Baker TB: Two studies of the clinical effectiveness of the nicotine patch with different counseling treatments. Chest. 1994, 105: 524-533. 10.1378/chest.105.2.524.

Richmond RL, Harris K, de Almeida Neto A: The transdermal nicotine patch: results of a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Med J Aust. 1994, 161: 130-135.

Levin ED, Westman EC, Stein RM, Carnahan E, Sanchez M, Herman S, Behm FM, Rose JE: Nicotine skin patch treatment increases abstinence, decreases withdrawal symptoms, and attenuates rewarding effects of smoking. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1994, 14: 41-49. 10.1097/00004714-199402000-00006.

Stapleton JA, Russell MA, Feyerabend C, Wiseman SM, Gustavsson G, Sawe U, Wiseman D: Dose effects and predictors of outcome in a randomized trial of transdermal nicotine patches in general practice. Addiction. 1995, 90: 31-42. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1995.tb01007.x.

Herrera N, Franco R, Herrera L, Partidas A, Rolando R, Fagerstrom KO: Nicotine gum, 2 and 4 mg, for nicotine dependence. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial within a behavior modification support program. Chest. 1995, 108: 447-451. 10.1378/chest.108.2.447.

Schneider NG, Olmstead R, Mody FV, Doan K, Franzon M, Jarvik ME, Steinberg C: Efficacy of a nicotine nasal spray in smoking cessation: a placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Addiction. 1995, 90: 1671-1682. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1995.tb02837.x.

Puska PKH, Vartiainen E, Urjanheimo E: Combined use of nicotine patch and gum compared with gum alone in smoking cessation: a clinical trial in North Karelia. Tabacco Control. 1995, 4: 231-235. 10.1136/tc.4.3.231.

Kornitzer M, Boutsen M, Dramaix M, Thijs J, Gustavsson G: Combined use of nicotine patch and gum in smoking cessation: a placebo-controlled clinical trial. Prev Med. 1995, 24: 41-47. 10.1006/pmed.1995.1006.

Dale LC, Hurt RD, Offord KP, Lawson GM, Croghan IT, Schroeder DR: High-dose nicotine patch therapy. Percentage of replacement and smoking cessation. Jama. 1995, 274: 1353-1358. 10.1001/jama.274.17.1353.

Campbell IA, Prescott RJ, Tjeder-Burton SM: Transdermal nicotine plus support in patients attending hospital with smoking-related diseases: a placebo-controlled study. Respir Med. 1996, 90: 47-51. 10.1016/S0954-6111(96)90244-9.

Gourlay SG, Forbes A, Marriner T, Pethica D, McNeil JJ: Double blind trial of repeated treatment with transdermal nicotine for relapsed smokers. Bmj. 1995, 311: 363-366.

Hall SM, Munoz RF, Reus VI, Sees KL, Duncan C, Humfleet GL, Hartz DT: Mood management and nicotine gum in smoking treatment: a therapeutic contact and placebo-controlled study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996, 64: 1003-1009. 10.1037/0022-006X.64.5.1003.

Leischow SJN, Franzo F, Hill M, Otte A, Merikle P, P E: Efficacy of the Nicotine Inhaler as an Adjunct to Smoking Cessation. American Journal of Health Behavior. 1996, 20: 364-371.

Schneider NG, Olmstead R, Nilsson F, Mody FV, Franzon M, Doan K: Efficacy of a nicotine inhaler in smoking cessation: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Addiction. 1996, 91: 1293-1306. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1996.tb03616.x.

Paoletti P, Fornai E, Maggiorelli F, Puntoni R, Viegi G, Carrozzi L, Corlando A, Gustavsson G, Sawe U, Giuntini C: Importance of baseline cotinine plasma values in smoking cessation: results from a double-blind study with nicotine patch. Eur Respir J. 1996, 9: 643-651. 10.1183/09031936.96.09040643.

Kinnunen T, Doherty K, Militello FS, Garvey AJ: Depression and smoking cessation: characteristics of depressed smokers and effects of nicotine replacement. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996, 64: 791-798. 10.1037/0022-006X.64.4.791.

Killen JD, Fortmann SP, Davis L, Varady A: Nicotine patch and self-help video for cigarette smoking cessation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997, 65: 663-672. 10.1037/0022-006X.65.4.663.

Blondal T, Franzon M, Westin A: A double-blind randomized trial of nicotine nasal spray as an aid in smoking cessation. Eur Respir J. 1997, 10: 1585-1590. 10.1183/09031936.97.10071585.

Hjalmarson A, Nilsson F, Sjostrom L, Wiklund O: The nicotine inhaler in smoking cessation. Arch Intern Med. 1997, 157: 1721-1728. 10.1001/archinte.157.15.1721.

Sonderskov J, Olsen J, Sabroe S, Meillier L, Overvad K: Nicotine patches in smoking cessation: a randomized trial among over-the-counter customers in Denmark. Am J Epidemiol. 1997, 145: 309-318.

Daughton D, Susman J, Sitorius M, Belenky S, Millatmal T, Nowak R, Patil K, Rennard SI: Transdermal nicotine therapy and primary care. Importance of counseling, demographic, and participant selection factors on 1-year quit rates. The Nebraska Primary Practice Smoking Cessation Trial Group. Arch Fam Med. 1998, 7: 425-430. 10.1001/archfami.7.5.425.

Perng RP, Hsieh WC, Chen YM, Lu CC, Chiang SJ: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of transdermal nicotine patch for smoking cessation. J Formos Med Assoc. 1998, 97: 547-551.

Ahluwalia JS, McNagny SE, Clark WS: Smoking cessation among inner-city African Americans using the nicotine transdermal patch. J Gen Intern Med. 1998, 13: 1-8. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00001.x.

Lewis SF, Piasecki TM, Fiore MC, Anderson JE, Baker TB: Transdermal nicotine replacement for hospitalized patients: a randomized clinical trial. Prev Med. 1998, 27: 296-303. 10.1006/pmed.1998.0266.

Davidson M, Epstein M, Burt R, Schaefer C, Whitworth G, McDonald A: Efficacy and safety of an over-the-counter transdermal nicotine patch as an aid for smoking cessation. Arch Fam Med. 1998, 7: 569-574. 10.1001/archfami.7.6.569.

Blondal T, Gudmundsson LJ, Olafsdottir I, Gustavsson G, Westin A: Nicotine nasal spray with nicotine patch for smoking cessation: randomised trial with six year follow up. Bmj. 1999, 318: 285-288.

Tonnesen P, Paoletti P, Gustavsson G, Russell MA, Saracci R, Gulsvik A, Rijcken B, Sawe U: Higher dosage nicotine patches increase one-year smoking cessation rates: results from the European CEASE trial. Collaborative European Anti-Smoking Evaluation. European Respiratory Society. Eur Respir J. 1999, 13: 238-246. 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.13b04.x.

Hays JT, Croghan IT, Schroeder DR, Offord KP, Hurt RD, Wolter TD, Nides MA, Davidson M: Over-the-counter nicotine patch therapy for smoking cessation: results from randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, and open label trials. Am J Public Health. 1999, 89: 1701-1707. 10.2105/AJPH.89.11.1701.

Bohadana A, Nilsson F, Rasmussen T, Martinet Y: Nicotine inhaler and nicotine patch as a combination therapy for smoking cessation: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2000, 160: 3128-3134. 10.1001/archinte.160.20.3128.

Bolliger CT, Zellweger JP, Danielsson T, van Biljon X, Robidou A, Westin A, Perruchoud AP, Sawe U: Smoking reduction with oral nicotine inhalers: double blind, randomised clinical trial of efficacy and safety. Bmj. 2000, 321: 329-333. 10.1136/bmj.321.7257.329.

Garvey AJ, Kinnunen T, Nordstrom BL, Utman CH, Doherty K, Rosner B, Vokonas PS: Effects of nicotine gum dose by level of nicotine dependence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2000, 2: 53-63. 10.1080/14622200050011303.

Wallstrom M, Nilsson F, Hirsch JM: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical evaluation of a nicotine sublingual tablet in smoking cessation. Addiction. 2000, 95: 1161-1171.

Wisborg K, Henriksen TB, Jespersen LB, Secher NJ: Nicotine patches for pregnant smokers: A randomized controlled study. Obstet Gynecol. 2000, 96: 967-971. 10.1016/S0029-7844(00)01071-1.

Etter JF, Laszlo E, Zellweger JP, Perrot C, Perneger TV: Nicotine replacement to reduce cigarette consumption in smokers who are unwilling to quit: a randomized trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002, 22: 487-495. 10.1097/00004714-200210000-00008.

Shiffman S, Gorsline J, Gorodetzky CW: Efficacy of over-the-counter nicotine patch. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002, 4: 477-483. 10.1080/1462220021000018416.

Glover ED, Glover PN, Franzon M, Sullivan CR, Cerullo CC, Howell RM, Keyes GG, Nilsson F, Hobbs GR: A comparison of a nicotine sublingual tablet and placebo for smoking cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002, 4: 441-450. 10.1080/1462220021000018443.

Shiffman S, Dresler CM, Hajek P, Gilburt SJ, Targett DA, Strahs KR: Efficacy of a nicotine lozenge for smoking cessation. Arch Intern Med. 2002, 162: 1267-1276. 10.1001/archinte.162.11.1267.

Glavas D, Rumboldt M, Rumboldt Z: Smoking cessation with nicotine replacement therapy among health care workers: randomized double-blind study. Croat Med J. 2003, 44: 219-224.

Wennike P, Danielsson T, Landfeldt B, Westin A, Tonnesen P: Smoking reduction promotes smoking cessation: results from a double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of nicotine gum with 2-year follow-up. Addiction. 2003, 98: 1395-1402. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00489.x.

Hughes JR, Novy P, Hatsukami DK, Jensen J, Callas PW: Efficacy of nicotine patch in smokers with a history of alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003, 27: 946-954.

Hanson K, Allen S, Jensen S, Hatsukami D: Treatment of adolescent smokers with the nicotine patch. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003, 5: 515-526. 10.1080/14622200307243.

Chou KR, Chen R, Lee JF, Ku CH, Lu RB: The effectiveness of nicotine-patch therapy for smoking cessation in patients with schizophrenia. Int J Nurs Stud. 2004, 41: 321-330. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2003.07.001.

Schuurmans MM, Diacon AH, van Biljon X, Bolliger CT: Effect of pre-treatment with nicotine patch on withdrawal symptoms and abstinence rates in smokers subsequently quitting with the nicotine patch: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2004, 99: 634-640. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00711.x.

Moolchan ET, Robinson ML, Ernst M, Cadet JL, Pickworth WB, Heishman SJ, Schroeder JR: Safety and efficacy of the nicotine patch and gum for the treatment of adolescent tobacco addiction. Pediatrics. 2005, 115: e407-414. 10.1542/peds.2004-1894.

Batra A, Klingler K, Landfeldt B, Friederich HM, Westin A, Danielsson T: Smoking reduction treatment with 4-mg nicotine gum: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005, 78: 689-696. 10.1016/j.clpt.2005.08.019.

Cooper TV, Klesges RC, Debon MW, Zbikowski SM, Johnson KC, Clemens LH: A placebo controlled randomized trial of the effects of phenylpropanolamine and nicotine gum on cessation rates and postcessation weight gain in women. Addict Behav. 2005, 30: 61-75. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.04.013.

Rennard SI, Glover ED, Leischow S, Daughton DM, Glover PN, Muramoto M, Franzon M, Danielsson T, Landfeldt B, Westin A: Efficacy of the nicotine inhaler in smoking reduction: A double-blind, randomized trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006, 8: 555-564. 10.1080/14622200600789916.

Tonnesen P, Mikkelsen K, Bremann L: Nurse-conducted smoking cessation in patients with COPD using nicotine sublingual tablets and behavioral support. Chest. 2006, 130: 334-342. 10.1378/chest.130.2.334.

Ahluwalia JS, Okuyemi K, Nollen N, Choi WS, Kaur H, Pulvers K, Mayo MS: The effects of nicotine gum and counseling among African American light smokers: a 2 × 2 factorial design. Addiction. 2006, 101: 883-891. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01461.x.

Myung SK, Seo HG, Park S, Kim Y, Kim DJ, Lee do H, Seong MW, Nam MH, Oh SW, Kim JA, Kim MY: Sociodemographic and smoking behavioral predictors associated with smoking cessation according to follow-up periods: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of transdermal nicotine patches. J Korean Med Sci. 2007, 22: 1065-1070. 10.3346/jkms.2007.22.6.1065.

Covey LS, Glassman AH, Jiang H, Fried J, Masmela J, LoDuca C, Petkova E, Rodriguez K: A randomized trial of bupropion and/or nicotine gum as maintenance treatment for preventing smoking relapse. Addiction. 2007, 102: 1292-1302. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01887.x.

Piper ME, Federman EB, McCarthy DE, Bolt DM, Smith SS, Fiore MC, Baker TB: Efficacy of bupropion alone and in combination with nicotine gum. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007, 9: 947-954. 10.1080/14622200701540820.

Oncken C, Cooney J, Feinn R, Lando H, Kranzler HR: Transdermal nicotine for smoking cessation in postmenopausal women. Addict Behav. 2007, 32: 296-309. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.04.004.

Croghan IT, Hurt RD, Dakhil SR, Croghan GA, Sloan JA, Novotny PJ, Rowland KM, Bernath A, Loots ML, Le-Lindqwister NA, Tschetter LK, Garneau SC, Flynn KA, Ebbert LP, Wender DB, Loprinzi CL: Randomized comparison of a nicotine inhaler and bupropion for smoking cessation and relapse prevention. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007, 82: 186-195. 10.4065/82.2.186.

Clavel F, Benhamou S, Company-Huertas A, Flamant R: Helping people to stop smoking: randomised comparison of groups being treated with acupuncture and nicotine gum with control group. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1985, 291: 1538-1539. 10.1136/bmj.291.6508.1538.

Fagerstrom KO: Effects of nicotine chewing gum and follow-up appointments in physician-based smoking cessation. Prev Med. 1984, 13: 517-527. 10.1016/0091-7435(84)90020-3.

Hall SM, Tunstall C, Rugg D, Jones RT, Benowitz N: Nicotine gum and behavioral treatment in smoking cessation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1985, 53: 256-258. 10.1037/0022-006X.53.2.256.

Russell MA, Merriman R, Stapleton J, Taylor W: Effect of nicotine chewing gum as an adjunct to general practitioner's advice against smoking. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983, 287: 1782-1785. 10.1136/bmj.287.6407.1782.

Page AR, Walters DJ, Schlegel RP, Best JA: Smoking cessation in family practice: the effects of advice and nicotine chewing gum prescription. Addict Behav. 1986, 11: 443-446. 10.1016/0306-4603(86)90025-0.

Sutton S, Hallett R: Smoking intervention in the workplace using videotapes and nicotine chewing gum. Prev Med. 1988, 17: 48-59. 10.1016/0091-7435(88)90071-0.

Harackiewicz JM, Blair LW, Sansone C, Epstein JA, Stuchell RN: Nicotine gum and self-help manuals in smoking cessation: an evaluation in a medical context. Addict Behav. 1988, 13: 319-330. 10.1016/0306-4603(88)90038-X.

Tonnesen P, Fryd V, Hansen M, Helsted J, Gunnersen AB, Forchammer H, Stockner M: Effect of nicotine chewing gum in combination with group counseling on the cessation of smoking. N Engl J Med. 1988, 318: 15-18.

Gilbert JR, Wilson DM, Best JA, Taylor DW, Lindsay EA, Singer J, Willms DG: Smoking cessation in primary care. A randomized controlled trial of nicotine-bearing chewing gum. J Fam Pract. 1989, 28: 49-55.

Segnan N, Ponti A, Battista RN, Senore C, Rosso S, Shapiro SH, Aimar D: A randomized trial of smoking cessation interventions in general practice in Italy. Cancer Causes Control. 1991, 2: 239-246. 10.1007/BF00052140.

Ockene JK, Kristeller J, Goldberg R, Amick TL, Pekow PS, Hosmer D, Quirk M, Kalan K: Increasing the efficacy of physician-delivered smoking interventions: a randomized clinical trial. J Gen Intern Med. 1991, 6: 1-8. 10.1007/BF02599381.

McGovern PG, Lando HA: An assessment of nicotine gum as an adjunct to freedom from smoking cessation clinics. Addict Behav. 1992, 17: 137-147. 10.1016/0306-4603(92)90018-Q.

Pirie PL, McBride CM, Hellerstedt W, Jeffery RW, Hatsukami D, Allen S, Lando H: Smoking cessation in women concerned about weight. Am J Public Health. 1992, 82: 1238-1243. 10.2105/AJPH.82.9.1238.

Nebot M, Cabezas C: Does nurse counseling or offer of nicotine gum improve the effectiveness of physician smoking-cessation advice?. Fam Pract Res J. 1992, 12: 263-270.

Richmond RL, Makinson RJ, Kehoe LA, Giugni AA, Webster IW: One-year evaluation of three smoking cessation interventions administered by general practitioners. Addict Behav. 1993, 18: 187-199. 10.1016/0306-4603(93)90049-F.

Niaura R, Goldstein MG, Abrams DB: Matching high- and low-dependence smokers to self-help treatment with or without nicotine replacement. Prev Med. 1994, 23: 70-77. 10.1006/pmed.1994.1010.

Fortmann SP, Killen JD: Nicotine gum and self-help behavioral treatment for smoking relapse prevention: results from a trial using population-based recruitment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995, 63: 460-468. 10.1037/0022-006X.63.3.460.

Gross J, Johnson J, Sigler L, Stitzer ML: Dose effects of nicotine gum. Addict Behav. 1995, 20: 371-381. 10.1016/0306-4603(94)00078-D.

Cinciripini PM, Cinciripini LG, Wallfisch A, Haque W, Van Vunakis H: Behavior therapy and the transdermal nicotine patch: effects on cessation outcome, affect, and coping. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996, 64: 314-323. 10.1037/0022-006X.64.2.314.

Nilsson P, Lundgren H, Soderstrom M, Fagerstrom KO, Nilsson-Ehle P: Effects of smoking cessation on insulin and cardiovascular risk factors--a controlled study of 4 months' duration. J Intern Med. 1996, 240: 189-194. 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1996.16844000.x.

Martin JE, Calfas KJ, Patten CA, Polarek M, Hofstetter CR, Noto J, Beach D: Prospective evaluation of three smoking interventions in 205 recovering alcoholics: one-year results of Project SCRAP-Tobacco. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997, 65: 190-194. 10.1037/0022-006X.65.1.190.

Niaura R, Abrams DB, Shadel WG, Rohsenow DJ, Monti PM, Sirota AD: Cue exposure treatment for smoking relapse prevention: a controlled clinical trial. Addiction. 1999, 94: 685-695. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.9456856.x.

Tonnesen P, Mikkelsen KL: Smoking cessation with four nicotine replacement regimes in a lung clinic. Eur Respir J. 2000, 16: 717-722. 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.16d25.x.

Hand S, Edwards S, Campbell IA, Cannings R: Controlled trial of three weeks nicotine replacement treatment in hospital patients also given advice and support. Thorax. 2002, 57: 715-718. 10.1136/thorax.57.8.715.

Molyneux A, Lewis S, Leivers U, Anderton A, Antoniak M, Brackenridge A, Nilsson F, McNeill A, West R, Moxham J, Britton J: Clinical trial comparing nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) plus brief counselling, brief counselling alone, and minimal intervention on smoking cessation in hospital inpatients. Thorax. 2003, 58: 484-488. 10.1136/thorax.58.6.484.

Swanson NA, Burroughs CC, Long MA, Lee RW: Controlled trial for smoking cessation in a Navy shipboard population using nicotine patch, sustained-release buproprion, or both. Mil Med. 2003, 168: 830-834.

Uyar M, Filiz A, Bayram N, Elbek O, Herken H, Topcu A, Dikensoy O, Ekinci E: A randomized trial of smoking cessation. Medication versus motivation. Saudi Med J. 2007, 28: 922-926.

Pollak KI, Oncken CA, Lipkus IM, Lyna P, Swamy GK, Pletsch PK, Peterson BL, Heine RP, Brouwer RJ, Fish L, Myers ER: Nicotine replacement and behavioral therapy for smoking cessation in pregnancy. Am J Prev Med. 2007, 33: 297-305. 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.05.006.

Prapavessis H, Cameron L, Baldi JC, Robinson S, Borrie K, Harper T, Grove JR: The effects of exercise and nicotine replacement therapy on smoking rates in women. Addict Behav. 2007, 32: 1416-1432. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.10.005.

Okuyemi KS, James AS, Mayo MS, Nollen N, Catley D, Choi WS, Ahluwalia JS: Pathways to health: a cluster randomized trial of nicotine gum and motivational interviewing for smoking cessation in low-income housing. Health Educ Behav. 2007, 34: 43-54. 10.1177/1090198106288046.

Gallagher SM, Penn PE, Schindler E, Layne W: A comparison of smoking cessation treatments for persons with schizophrenia and other serious mental illnesses. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2007, 39: 487-497.

Hotham ED, Gilbert AL, Atkinson ER: A randomised-controlled pilot study using nicotine patches with pregnant women. Addict Behav. 2006, 31: 641-648. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.042.

Jorenby DE, Leischow SJ, Nides MA, Rennard SI, Johnston JA, Hughes AR, Smith SS, Muramoto ML, Daughton DM, Doan K, Fiore MC, Baker TB: A controlled trial of sustained-release bupropion, a nicotine patch, or both for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 1999, 340: 685-691. 10.1056/NEJM199903043400903.

Randomised trial of nicotine patches in general practice: results at one year. Imperial Cancer Research Fund General Practice Research Group. Bmj. 1994, 308: 1476-1477.

George TP, Vessicchio JC, Sacco KA, Weinberger AH, Dudas MM, Allen TM, Creeden CL, Potenza MN, Feingold A, Jatlow PI: A placebo-controlled trial of bupropion combined with nicotine patch for smoking cessation in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2008, 63: 1092-1096. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.11.002.

McCarthy DE, Piasecki TM, Lawrence DL, Jorenby DE, Shiffman S, Fiore MC, Baker TB: A randomized controlled clinical trial of bupropion SR and individual smoking cessation counseling. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008, 10: 717-729. 10.1080/14622200801968343.

Schmitz JM, Stotts AL, Mooney ME, Delaune KA, Moeller GF: Bupropion and cognitive-behavioral therapy for smoking cessation in women. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007, 9: 699-709. 10.1080/14622200701365335.

Fossati R, Apolone G, Negri E, Compagnoni A, La Vecchia C, Mangano S, Clivio L, Garattini S: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial of bupropion for smoking cessation in primary care. Arch Intern Med. 2007, 167: 1791-1797. 10.1001/archinte.167.16.1791.

Evins AE, Cather C, Culhane MA, Birnbaum A, Horowitz J, Hsieh E, Freudenreich O, Henderson DC, Schoenfeld DA, Rigotti NA, Goff DC: A 12-week double-blind, placebo-controlled study of bupropion sr added to high-dose dual nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation or reduction in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007, 27: 380-386. 10.1097/01.jcp.0b013e3180ca86fa.

Grant KM, Kelley SS, Smith LM, Agrawal S, Meyer JR, Romberger DJ: Bupropion and nicotine patch as smoking cessation aids in alcoholics. Alcohol. 2007, 41: 381-391. 10.1016/j.alcohol.2007.03.011.

Muramoto ML, Leischow SJ, Sherrill D, Matthews E, Strayer LJ: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 2 dosages of sustained-release bupropion for adolescent smoking cessation. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007, 161: 1068-1074. 10.1001/archpedi.161.11.1068.

Brown RA, Niaura R, Lloyd-Richardson EE, Strong DR, Kahler CW, Abrantes AM, Abrams D, Miller IW: Bupropion and cognitive-behavioral treatment for depression in smoking cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007, 9: 721-730. 10.1080/14622200701416955.

Rigotti NA, Thorndike AN, Regan S, McKool K, Pasternak RC, Chang Y, Swartz S, Torres-Finnerty N, Emmons KM, Singer DE: Bupropion for smokers hospitalized with acute cardiovascular disease. Am J Med. 2006, 119: 1080-1087. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.04.024.

Haggstram FM, Chatkin JM, Sussenbach-Vaz E, Cesari DH, Fam CF, Fritscher CC: A controlled trial of nortriptyline, sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation: preliminary results. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2006, 19: 205-209. 10.1016/j.pupt.2005.05.003.

Killen JD, Fortmann SP, Murphy GM, Hayward C, Arredondo C, Cromp D, Celio M, Abe L, Wang Y, Schatzberg AF: Extended treatment with bupropion SR for cigarette smoking cessation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006, 74: 286-294. 10.1037/0022-006X.74.2.286.

Nides M, Oncken C, Gonzales D, Rennard S, Watsky EJ, Anziano R, Reeves KR: Smoking cessation with varenicline, a selective alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptor partial agonist: results from a 7-week, randomized, placebo- and bupropion-controlled trial with 1-year follow-up. Arch Intern Med. 2006, 166: 1561-1568. 10.1001/archinte.166.15.1561.

Gonzales D, Rennard SI, Nides M, Oncken C, Azoulay S, Billing CB, Watsky EJ, Gong J, Williams KE, Reeves KR: Varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2006, 296: 47-55. 10.1001/jama.296.1.47.

Jorenby DE, Hays JT, Rigotti NA, Azoulay S, Watsky EJ, Williams KE, Billing CB, Gong J, Reeves KR: Efficacy of varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs placebo or sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2006, 296: 56-63. 10.1001/jama.296.1.56.

Evins AE, Cather C, Deckersbach T, Freudenreich O, Culhane MA, Olm-Shipman CM, Henderson DC, Schoenfeld DA, Goff DC, Rigotti NA: A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of bupropion sustained-release for smoking cessation in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005, 25: 218-225. 10.1097/01.jcp.0000162802.54076.18.

Wagena EJ, Knipschild PG, Huibers MJ, Wouters EF, van Schayck CP: Efficacy of bupropion and nortriptyline for smoking cessation among people at risk for or with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med. 2005, 165: 2286-2292. 10.1001/archinte.165.19.2286.

Holt S, Timu-Parata C, Ryder-Lewis S, Weatherall M, Beasley R: Efficacy of bupropion in the indigenous Maori population in New Zealand. Thorax. 2005, 60: 120-123. 10.1136/thx.2004.030239.

Zellweger JP, Boelcskei PL, Carrozzi L, Sepper R, Sweet R, Hider AZ: Bupropion SR vs placebo for smoking cessation in health care professionals. Am J Health Behav. 2005, 29: 240-249.

Myles PS, Leslie K, Angliss M, Mezzavia P, Lee L: Effectiveness of bupropion as an aid to stopping smoking before elective surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Anaesthesia. 2004, 59: 1053-1058. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.03943.x.

Aubin HJ, Lebargy F, Berlin I, Bidaut-Mazel C, Chemali-Hudry J, Lagrue G: Efficacy of bupropion and predictors of successful outcome in a sample of French smokers: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Addiction. 2004, 99: 1206-1218. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00814.x.

Dalsgareth OJ, Hansen NC, Soes-Petersen U, Evald T, Hoegholm A, Barber J, Vestbo J: A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 6-month trial of bupropion hydrochloride sustained-release tablets as an aid to smoking cessation in hospital employees. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004, 6: 55-61.

Hatsukami DK, Rennard S, Patel MK, Kotlyar M, Malcolm R, Nides MA, Dozier G, Bars MP, Jamerson BD: Effects of sustained-release bupropion among persons interested in reducing but not quitting smoking. Am J Med. 2004, 116: 151-157. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.07.018.

Simon JA, Duncan C, Carmody TP, Hudes ES: Bupropion for smoking cessation: a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2004, 164: 1797-1803. 10.1001/archinte.164.16.1797.

Killen JD, Robinson TN, Ammerman S, Hayward C, Rogers J, Stone C, Samuels D, Levin SK, Green S, Schatzberg AF: Randomized clinical trial of the efficacy of bupropion combined with nicotine patch in the treatment of adolescent smokers. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004, 72: 729-735. 10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.729.

Tonstad S, Farsang C, Klaene G, Lewis K, Manolis A, Perruchoud AP, Silagy C, van Spiegel PI, Astbury C, Hider A, Sweet R: Bupropion SR for smoking cessation in smokers with cardiovascular disease: a multicentre, randomised study. Eur Heart J. 2003, 24: 946-955. 10.1016/S0195-668X(03)00003-4.

Tonnesen P, Tonstad S, Hjalmarson A, Lebargy F, Van Spiegel PI, Hider A, Sweet R, Townsend J: A multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 1-year study of bupropion SR for smoking cessation. J Intern Med. 2003, 254: 184-192. 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01185.x.

Hurt RD, Krook JE, Croghan IT, Loprinzi CL, Sloan JA, Novotny PJ, Kardinal CG, Knost JA, Tirona MT, Addo F, Morton RF, Michalak JC, Schaefer PL, Porter PA, Stella PJ: Nicotine patch therapy based on smoking rate followed by bupropion for prevention of relapse to smoking. J Clin Oncol. 2003, 21: 914-920. 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.160.

Lerman C, Shields PG, Wileyto EP, Audrain J, Pinto A, Hawk L, Krishnan S, Niaura R, Epstein L: Pharmacogenetic investigation of smoking cessation treatment. Pharmacogenetics. 2002, 12: 627-634. 10.1097/00008571-200211000-00007.

Lerman C, Roth D, Kaufmann V, Audrain J, Hawk L, Liu A, Niaura R, Epstein L: Mediating mechanisms for the impact of bupropion in smoking cessation treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002, 67: 219-223. 10.1016/S0376-8716(02)00067-4.

George TP, Vessicchio JC, Termine A, Bregartner TA, Feingold A, Rounsaville BJ, Kosten TR: A placebo controlled trial of bupropion for smoking cessation in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2002, 52: 53-61. 10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01339-2.

Hall SM, Humfleet GL, Reus VI, Munoz RF, Hartz DT, Maude-Griffin R: Psychological intervention and antidepressant treatment in smoking cessation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002, 59: 930-936. 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.930.

Tashkin D, Kanner R, Bailey W, Buist S, Anderson P, Nides M, Gonzales D, Dozier G, Patel MK, Jamerson B: Smoking cessation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised trial. Lancet. 2001, 357: 1571-1575. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04724-3.

Hertzberg MA, Moore SD, Feldman ME, Beckham JC: A preliminary study of bupropion sustained-release for smoking cessation in patients with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001, 21: 94-98. 10.1097/00004714-200102000-00017.

Evins AE, Mays VK, Rigotti NA, Tisdale T, Cather C, Goff DC: A pilot trial of bupropion added to cognitive behavioral therapy for smoking cessation in schizophrenia. Nicotine Tob Res. 2001, 3: 397-403. 10.1080/14622200110073920.

Gonzales DH, Nides MA, Ferry LH, Kustra RP, Jamerson BD, Segall N, Herrero LA, Krishen A, Sweeney A, Buaron K, Metz A: Bupropion SR as an aid to smoking cessation in smokers treated previously with bupropion: a randomized placebo-controlled study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2001, 69: 438-444. 10.1067/mcp.2001.115750.

Hays JT, Hurt RD, Rigotti NA, Niaura R, Gonzales D, Durcan MJ, Sachs DP, Wolter TD, Buist AS, Johnston JA, White JD: Sustained-release bupropion for pharmacologic relapse prevention after smoking cessation. a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2001, 135: 423-433.

Hurt RD, Sachs DP, Glover ED, Offord KP, Johnston JA, Dale LC, Khayrallah MA, Schroeder DR, Glover PN, Sullivan CR, Croghan IT, Sullivan PM: A comparison of sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 1997, 337: 1195-1202. 10.1056/NEJM199710233371703.

Aubin HJ, Bobak A, Britton JR, Oncken C, Billing CB, Gong J, Williams KE, Reeves KR: Varenicline versus transdermal nicotine patch for smoking cessation: results from a randomised open-label trial. Thorax. 2008, 63: 717-724. 10.1136/thx.2007.090647.

Niaura R, Hays JT, Jorenby DE, Leone FT, Pappas JE, Reeves KR, Williams KE, Billing CB: The efficacy and safety of varenicline for smoking cessation using a flexible dosing strategy in adult smokers: a randomized controlled trial. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008, 24: 1931-1941. 10.1185/03007990802177523.

Williams KE, Reeves KR, Billing CB, Pennington AM, Gong J: A double-blind study evaluating the long-term safety of varenicline for smoking cessation. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007, 23: 793-801. 10.1185/030079907X182185.

Tsai ST, Cho HJ, Cheng HS, Kim CH, Hsueh KC, Billing CB, Williams KE: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of varenicline, a selective alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, as a new therapy for smoking cessation in Asian smokers. Clin Ther. 2007, 29: 1027-1039. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.06.011.

Nakamura M, Oshima A, Fujimoto Y, Maruyama N, Ishibashi T, Reeves KR: Efficacy and tolerability of varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, in a 12-week, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-response study with 40-week follow-up for smoking cessation in Japanese smokers. Clin Ther. 2007, 29: 1040-1056. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.06.012.

Burstein AH, Fullerton T, Clark DJ, Faessel HM: Pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability after single and multiple oral doses of varenicline in elderly smokers. J Clin Pharmacol. 2006, 46: 1234-1240. 10.1177/0091270006291837.

Oncken C, Gonzales D, Nides M, Rennard S, Watsky E, Billing CB, Anziano R, Reeves K: Efficacy and safety of the novel selective nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, varenicline, for smoking cessation. Arch Intern Med. 2006, 166: 1571-1577. 10.1001/archinte.166.15.1571.

Tonstad S, Tonnesen P, Hajek P, Williams KE, Billing CB, Reeves KR: Effect of maintenance therapy with varenicline on smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2006, 296: 64-71. 10.1001/jama.296.1.64.

Tonstad S: Smoking cessation efficacy and safety of varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptor partial agonist. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2006, 21: 433-436.

Houston TK, Allison JJ, Person S, Kovac S, Williams OD, Kiefe CI: Post-myocardial infarction smoking cessation counseling: associations with immediate and late mortality in older Medicare patients. Am J Med. 2005, 118: 269-275. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.12.007.

Lancaster T, Hajek P, Stead LF, West R, Jarvis MJ: Prevention of relapse after quitting smoking: a systematic review of trials. Arch Intern Med. 2006, 166: 828-835. 10.1001/archinte.166.8.828.

Salanti G, Higgins JP, Ades AE, Ioannidis JP: Evaluation of networks of randomized trials. Stat Methods Med Res. 2008, 17: 279-301. 10.1177/0962280207080643.

Bucher HC, Guyatt GH, Griffith LE, Walter SD: The results of direct and indirect treatment comparisons in meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997, 50: 683-691. 10.1016/S0895-4356(97)00049-8.

Mills EJ, Wu P, Rachlis B, Arora P, Deveraux PJ, Perri D: Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Mortality and Events With Statin Treatments A Network Meta-Analysis Involving More Than 65,000 Patients. JACC. 2008, 52: 1769-1781.

Acknowledgements

We thank Chris O'Regan for assistance with this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

EM, PW and KW have consulted to Pfizer Ltd in the past 5 years. No stock ownership is reported. DS is an employee of Pfizer Ltd. JE declares no conflict of interest. Pfizer Ltd. Is the maker of an NRT product and varenicline. EM and KW are supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Canada Research Chairs.

Authors' contributions

EM, PW, DS, KW and COR conceived the protocol. EM, PW, KW did the search strategies. EM, PW, JO, KW did the data abstraction and analysis. EM, PW, JO, KW wrote the first draft of the manuscript. EM, PW, DS, JO, KW approved the final submitted version.

Electronic supplementary material

12954_2009_156_MOESM1_ESM.DOC

Additional file 1: Characteristics of included studies. Supplementary Tables addressing study populations and interventions. (DOC 678 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Mills, E.J., Wu, P., Spurden, D. et al. Efficacy of pharmacotherapies for short-term smoking abstinance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Harm Reduct J 6, 25 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7517-6-25

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7517-6-25