Abstract

Aboriginal people experience a disproportionate burden of HIV infection among the adult population in Canada; however, less is known regarding the prevalence and characteristics of HIV positivity among drug-using and street-involved Aboriginal youth. We examined HIV seroprevalence and risk factors among a cohort of 529 street-involved youth in Vancouver, Canada. At baseline, 15 (2.8%) were HIV positive, of whom 7 (46.7%) were Aboriginal. Aboriginal ethnicity was a significant correlate of HIV infection (odds ratio = 2.87, 95%CI: 1.02 – 8.09). Of the HIV positive participants, 2 (28.6%) Aboriginals and 6 (75.0%) non-Aboriginals reported injection drug use; furthermore, hepatitis C co-infection was significantly less common among Aboriginal participants (p = 0.041). These findings suggest that factors other than injection drug use may promote HIV transmission among street-involved Aboriginal youth, and provide further evidence that culturally appropriate and evidence-based interventions for HIV prevention among Aboriginal young people are urgently required.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Aboriginal populations in Canada are contending with a disproportionate burden of HIV infection [1]. Although only 3.3% of Canadians identify as American Indian, First Nations, Inuit, or Métis, Aboriginal people accounted for 18.8% of HIV test reports in 1998 and 27.3% in 2006 [1, 2]. Within adult Aboriginal communities, injection drug use is considered to be one of the primary modes of HIV transmission, accounting for approximately 60% of new HIV infections [1]. Among injection drug using populations, Aboriginal ethnicity has also been shown to be an independent predictor of HIV seroconversion [3, 4]. Elevated rates of HIV incidence have also been observed among young Aboriginal injection drug users [5, 6]. Although the prevalence and risk factors for HIV infection among Aboriginal injection drug users have been relatively well-described, there exists little information on HIV infection among populations of street-involved Aboriginal youth with heterogeneous (i.e., injection and non-injection) drug-using characteristics and patterns. Since HIV infections typically occur at earlier ages among Aboriginal people as compared to the non-Aboriginal population [1], research examining the risk factors for HIV infection among this age group is of particular salience to public health programming and policy. We undertook this study to examine the prevalence and characteristics of HIV positive status among a cohort of street-involved youth in Vancouver.

Methods

The At Risk Youth Study (ARYS) is a prospective cohort of drug-using and street-involved youth that has been described in detail previously [7]. Snowball sampling and extensive street-based outreach was conducted to recruit participants into the study. Eligibility criteria included: being between the age of 14 and 26, self-reported use of illicit drugs other than or in addition to marijuana in the past 30 days, and the provision of informed consent. The study has been approved by the University of British Columbia/Providence Health Care Research Ethics Board. We also sought to ensure that the research protocols were in accordance with the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Guidelines for Health Research Involving Aboriginal People [8].

All participants who completed a baseline survey between September, 2005 and October, 2006 were included in this analysis. At study entry, each participant completed an interviewer-administered questionnaire and provided blood samples for HIV and hepatitis C (HCV) serology. American Indian/Aboriginal ethnicity (yes vs. no) was defined as self-identified First Nations, Aboriginal, Inuit, or Métis origin. Other variables that were included in this analysis included age (<22 vs. ≥ 22), sex (female vs. male), Downtown Eastside (DTES) residency, homelessness, injection drug use, syringe sharing, history of incarceration, history of sex work, history of sexual abuse, ever engaging in anal intercourse, condom use (inconsistent vs. consistent), and for males, ever engaging in sex with men. As described previously [9], individuals were recorded as residents of the Downtown Eastside if they responded "DTES" to the question, "What local neighbourhoods or cities have you lived in during the past 6 months". Individuals classified as DTES residents may include those who are homeless and sleep or spend most of their time in the neighbourhood. To be consistent with previous studies, syringe sharing included lending or borrowing used syringes, and inconsistent condom use was defined as not always using a condom during vaginal and anal intercourse with all regular and casual partners [10, 11].

Pearson's chi-square test was used to determine the factors associated with HIV positive status at baseline (Table 1). Fisher's exact test was used when one or more of the cell counts was less than or equal to five. Since we only observed 15 positive diagnoses, multivariate analysis was not conducted; however, the individual characteristics of each HIV positive participant were aggregated and are presented in Table 2.

Findings

A total of 529 participants completed a baseline survey and were eligible for this analysis. The median age of the sample was 22.0 (interquartile range: 19.9 – 23.9), 159 (30.1%) were female, 404 (76.4%) had been homeless in the past six months, and 221 (41.8%) reported ever injecting. In total, 127 (24.0%) participants self-identified as Aboriginal, American Indian, First Nations, Inuit, or Métis.

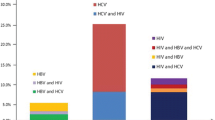

Of the entire sample, 15 (2.8%) tested positive for HIV, of whom 7 (46.7%) were of Aboriginal ethnicity. As shown in Table 1, Aboriginal ethnicity was associated with HIV infection (odds ratio [OR] = 2.87, 95%CI: 1.02 – 8.09), as was injection drug use (OR = 2.75, 95%CI: 0.98 – 7.73) and sex trade work (OR = 4.35, 95%CI: 1.54 – 12.26). Younger participants were less likely to be infected with HIV (OR = 0.14, 95%CI: 0.03 – 0.65).

Among the HIV positive individuals (Table 2), only 2 (28.6%) Aboriginal participants reported injecting drugs and none reported sharing syringes. HIV-infected Aboriginal youth were significantly less likely to be co-infected with HCV (Fisher's exact test p-value = 0.041).

Discussion

Among a community-based sample of street-involved youth, Aboriginal participants were more than two and a half times more likely to be infected with HIV. The prevalence of HIV among Aboriginal youth in this sample was 5.5%, a proportion similar to that reported in a recent study of at-risk Aboriginal youth in two cities in British Columbia [12]. The prevalence of HIV among Aboriginal youth in this setting is also substantially higher than those that have been observed among street youth populations in Montréal (1.9%) and Toronto (2.2%) [13, 14]. Furthermore, the fact that HIV-infected Aboriginal youth were less likely to report injection drug use and be co-infected with HCV suggests that unsafe sexual activity, sex work, and other unmeasured antecedent factors may be responsible for a significant proportion of infections. These findings are concerning and suggest that immediate and culturally appropriate policy and programmatic remedies are required to prevent further infections among Aboriginal youth and to provide increased resources to those individuals who are already infected.

Other factors that were associated with HIV positivity in bivariate analysis are similar to other studies of HIV infection among street-involved youth in Canada. For example, older age, history of injection drug use, and sex work were also all significant correlates of HIV infection among a cohort of street-involved youth in Montreal [14]. Of particular relevance to our setting is the high prevalence of incarceration observed among both HIV positive and negative participants – in fact, all seven HIV positive Aboriginal individuals also reported a history of incarceration. Given that incarceration has been associated with both HIV risk behaviours [15] and HIV incidence [16] in Vancouver, interventions to reduce street youths' exposure to correctional environments and the HIV-related harms associated with them are in urgent need of evaluation. Of further concern is that over half of HIV-infected Aboriginal participants reported experiencing sexual abuse, a finding which supports a recent study showing strong associations between sexual abuse and HIV risk behaviours among this population [17]. These results suggest that programs which aim to support HIV positive Aboriginal young people should recognize and address the lasting effects of historical trauma and cultural assimilation stemming from the Canadian residential school system on current levels of sexual abuse, substance use, and other HIV-related vulnerabilities.

Recently, the federal government of Canada announced that funding to community and regional HIV programs would be redirected towards the Canadian HIV Vaccine Initiative [18, 19]. Although research funding for HIV vaccines is undoubtedly integral to long-term HIV strategies, the observed prevalence of HIV among Aboriginal youth observed in this and other studies supports statements made by the Assembly of First Nations that, relative to the size of the epidemic, HIV programs for Aboriginal programs are chronically under-funded and are in urgent need of further investment [20]. The Canadian Aboriginal AIDS Network has also argued that a serious lack of youth-specific HIV prevention programmes for Aboriginal youth exists across the country, and as such a national strategy on Aboriginal youth HIV/AIDS prevention is required [21]. Given these concerns, research and interventions that seek to identify effective strategies for addressing HIV infection and related vulnerabilities among Aboriginal young people should be a public health priority.

Our study is limited by its nonrandom sampling methodology that precludes generalization to the larger street-involved population in British Columbia. However, the sociodemographic characteristics of our sample are similar to those observed among other street youth studies in this setting [22, 23]. Secondly, stigmatized behaviours such as injection drug use and syringe sharing may be underreported, particularly as the reliability and validity of self-report among samples of Aboriginal youth has been questioned by some authors [24]. However, a review of studies assessing the reliability and validity of self-reported drug use and HIV risk behaviours among injection drug users concluded that these measures are sufficiently valid [25]. It is also important to note that the prevalence of injection drug use and related behaviours reported in our study are similar to those from a recently published analysis of risk behaviours among Aboriginal youth who use drugs in Vancouver [12]. Even if socially desirable reporting were present in the data, we have no reason to believe that Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal participants would differ with respect to the likelihood of the underreporting of certain behaviours. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that biological evidence (i.e., hepatitis C serostatus) supports the self-reported data suggesting a higher proportion of sexually acquired HIV among Aboriginal participants. Finally, although we recognize that HIV vulnerability among Aboriginal populations is produced through a complex interplay of social, structural, and historical factors such as poverty, cultural oppression, and the multigenerational effects of the residential school system [6], we were unable to measure and characterize many of these effects.

In summary, we observed an alarmingly high prevalence of HIV infection among street-involved Aboriginal youth. Our findings demonstrate that urgent and culturally appropriate action is required to address the pervasive inequities that perpetuate marginalization and heightened vulnerability to HIV among Aboriginal young people in Canada.

References

Public Health Agency of Canada: HIV/AIDS Epi Updates, November 2007. [http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/aids-sida/publication/epi/pdf/epi2007_e.pdf]

Public Health Agency of Canada: Understanding the HIV/AIDS Epidemic among Aboriginal Peoples in Canada: The Community at a Glance. [http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/epiu-aepi/epi-note/pdf/epi_notes_aboriginal_e.pdf]

Wood E, Montaner JS, Li K, Zhang R, Barney L, Strathdee SA, Tyndall MW, Kerr T: Burden of HIV infection among Aboriginal injection drug users in Vancouver, British Columbia. Am J Public Health. 2008, 98: 515-519. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.114595.

Craib KJ, Spittal PM, Wood E, Laliberte N, Hogg RS, Li K, Heath K, Tyndall MW, O'Shaughnessy MV, Schechter MT: Risk factors for elevated HIV incidence among Aboriginal injection drug users in Vancouver. CMAJ. 2003, 168: 19-24.

Miller CL, Tyndall M, Spittal P, Li K, LaLiberte N, Schechter MT: HIV incidence and associated risk factors among young injection drug users. AIDS. 2002, 16: 491-493. 10.1097/00002030-200202150-00025.

Miller CL, Strathdee SA, Spittal PM, Kerr T, Li K, Schechter MT, Wood E: Elevated rates of HIV infection among young Aboriginal injection drug users in a Canadian setting. Harm Reduct J. 2006, 3: 9-10.1186/1477-7517-3-9.

Wood E, Stoltz JA, Montaner JS, Kerr T: Evaluating methamphetamine use and risks of injection initiation among street youth: The ARYS study. Harm Reduct J. 2006, 3: 18-10.1186/1477-7517-3-18.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research: Guidelines for Health Research Involving Aboriginal People. [http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/documents/ethics_aboriginal_guidelines_e.pdf]

Maas B, Fairbairn N, Kerr T, Li K, Montaner JS, Wood E: Neighborhood and HIV infection among IDU: Place of residence independently predicts HIV infection among a cohort of injection drug users. Health Place. 2007, 13: 432-439. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2006.05.005.

Marshall BDL, Kerr T, Shoveller JA, Patterson TL, Buxton JA, Wood E: Homelessness and unstable housing associated with an increased risk of HIV and STI transmission among street-involved youth. 2008,

Kerr T, Tyndall M, Li K, Montaner J, Wood E: Safer injection facility use and syringe sharing in injection drug users. Lancet. 2005, 366: 316-318. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66475-6.

Spittal PM, Craib KJP, Teegee M, Baylis C, Christian WM, Moniruzzaman AKM, Schechter MT, Partnership CP: The Cedar Project: Prevalence and correlates of HIV infection among young Aboriginal people who use drugs in two Canadian cities. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2007, 66: 226-240.

DeMatteo D, Major C, Block B, Coates R, Fearon M, Goldberg E, King SM, Millson M, O'Shaughnessy M, Read SE: Toronto street youth and HIV/AIDS: Prevalence, demographics, and risks. J Adolesc Health. 1999, 25: 358-366. 10.1016/S1054-139X(99)00059-2.

Roy E, Haley N, Leclerc P, Lemire N, Boivin JF, Frappier JY, Claessens C: Prevalence of HIV infection and risk behaviours among Montreal street youth. Int J STD AIDS. 2000, 11: 241-247. 10.1258/0956462001915778.

Milloy MJ, Wood E, Small W, Tyndall M, Lai C, Montaner J, Kerr T: Incarceration experiences in a cohort of active injection drug users. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2008, 1-7.

Tyndall MW, Currie S, Spittal P, Li K, Wood E, O'Shaughnessy MV, Schechter MT: Intensive injection cocaine use as the primary risk factor in the Vancouver HIV-1 epidemic. AIDS. 2003, 17: 887-893. 10.1097/00002030-200304110-00014.

Cedar Project P, Pearce ME, Christian WM, Patterson K, Norris K, Moniruzzaman A, Craib KJ, Schechter MT, Spittal PM: The Cedar Project: Historical trauma, sexual abuse and HIV risk among young Aboriginal people who use injection and non-injection drugs in two Canadian cities. Soc Sci Med. 2008, 66: 2185-2194. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.034.

Galloway G: Ottawa redirects AIDS funds for Gates initiative. Globe and Mail, National edition. November 29. 2007, A1-

Public Health Agency of Canada: CPHO Statement on HIV/AIDS Funding. [http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/media/cpho-acsp/hiv1205-eng.php]

Assembly of First Nations: Canada's First Nations HIV/AIDS Epidemic. [http://www.afn.ca/article.asp?id=2800]

Prentice T, Norton A, Amaral A, Harper R, Unrau D, Myrah J, Nyce FB, Jackson B, Barlow K: A community-based approach to developing HIV prevention messages for Canadian Aboriginal youth [abstract]. Can J Infect Dis. 2004, 15: 488P-

Martin I, Lampinen TM, McGhee D: Methamphetamine use among marginalized youth in British Columbia. Can J Public Health. 2006, 97: 320-324.

Ochnio JJ, Patrick D, Ho M, Talling DN, Dobson SR: Past infection with hepatitis A virus among Vancouver street youth, injection drug users and men who have sex with men: Implications for vaccination programs. CMAJ. 2001, 165: 293-297.

Majumdar BB, Chambers TL, Roberts J: Community-based, culturally sensitive HIV/AIDS education for Aboriginal adolescents: Implications for nursing practice. J Transcult Nurs. 2004, 15: 69-73. 10.1177/1043659603260015.

Darke S: Self-report among injecting drug users: A review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998, 51: 253-263. 10.1016/S0376-8716(98)00028-3.

Acknowledgements

We would particularly like to thank the ARYS participants for their willingness to be included in the study, as well as current and past ARYS investigators and staff. We would specifically like to thank Deborah Graham, Tricia Collingham, Leslie Rae, Caitlin Johnston, Steve Kain, and Calvin Lai for their research and administrative assistance. The study was supported by the US National Institutes of Health and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). Brandon Marshall is supported by training awards from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR) and CIHR. Thomas Kerr is supported by fellowships from MSFHR and CIHR.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

BM, TK, CL, KL, and EW declare that they have no competing interests. JM has received grants from, served as an ad hoc adviser to, or spoken at events sponsored by Abbott, Argos Therapeutics, Bioject Inc., Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Hoffmann-La Roche, Janssen-Ortho, Merck Frosst, Panacos, Pfizer, Schering, Serono Inc., TheraTechnologies, Tibotec (J&J), and Trimeris.

Authors' contributions

EW had full access to all of the data and takes responsibility for the integrity of the results and the accuracy of the statistical analysis. BM conceived the study concept and design and was responsible for the composition of the manuscript.

The statistical analysis was conducted by KL and the interpretation of the results was performed by BM, CL, EW, JM and TK. The manuscript was edited and revised by BM, CL, EW, JM and TK. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Marshall, B.D., Kerr, T., Livingstone, C. et al. High prevalence of HIV infection among homeless and street-involved Aboriginal youth in a Canadian setting. Harm Reduct J 5, 35 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7517-5-35

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7517-5-35