Abstract

Background

Allergic rhinitis (AR) affects up to 80% of children with asthma and increases asthma severity. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) is a key mediator of allergic inflammation. The role of the TSLP gene (TSLP) in the pathogenesis of AR has not been studied.

Objective

To test for associations between variants in TSLP, TSLP-related genes, and AR in children with asthma.

Methods

We genotyped 15 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in TSLP, OX40L, IL7R, and RXRα in three independent cohorts: 592 asthmatic Costa Rican children and their parents, 422 nuclear families of North American children with asthma, and 239 Swedish children with asthma. We tested for associations between these SNPs and AR. As we previously reported sex-specific effects for TSLP, we performed overall and sex-stratified analyses. We additionally performed secondary analyses for gene-by-gene interactions.

Results

Across the three cohorts, the T allele of TSLP SNP rs1837253 was undertransmitted in boys with AR and asthma as compared to boys with asthma alone. The SNP was associated with reduced odds for AR (odds ratios ranging from 0.56 to 0.63, with corresponding Fisher's combined P value of 1.2 × 10-4). Our findings were significant after accounting for multiple comparisons. SNPs in OX40L, IL7R, and RXRα were not consistently associated with AR in children with asthma. There were nominally significant interactions between gene pairs.

Conclusions

TSLP SNP rs1837253 is associated with reduced odds for AR in boys with asthma. Our findings support a role for TSLP in the pathogenesis of AR in children with asthma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Allergic rhinitis (AR) is a common chronic disease, affecting 10-30% of adults and 40% of children [1]. Characterized by nasal congestion, itching, rhinorrhea, and sneezing, AR decreases school and work productivity. AR is a risk factor for asthma exacerbations and asthma-related hospitalization [2, 3]. Up to 80% of children with asthma have AR [4], and treatment of comorbid AR reduces the odds of asthma-related healthcare by up to 80% [5]. A better understanding of the pathophysiology of AR could decrease morbidity in asthmatics and in children overall.

The role of thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) in the pathogenesis of AR has not been extensively studied. TSLP is an interleukin (IL)-7-like cytokine that triggers dendritic cells and mast cells to induce T helper (Th)2 inflammatory responses (Figure 1) [6, 7]. The gene for TSLP (TSLP) is expressed by epithelial cells of the lung, skin and gut [8]. In humans, TSLP has been linked to the pathogenesis of asthma [9–11], atopic dermatitis [6], and eosinophilic esophagitis [12]. A few in vitro and murine studies with small sample size have examined TSLP expression in allergic rhinitis (AR) [13–16]. To date, there have been no genetic association studies of TSLP and AR.

The effects of TSLP are influenced by its heterodimeric receptor, costimulatory molecules, transcriptional regulators, and other cytokines (Figure 1). Therefore, we were also interested in examining the association between AR and genes related to TSLP, including OX40L, IL7R, and RXRα. Expressed by antigen-presenting cells, OX40L is an essential costimulatory mediator of TSLP-mediated Th2 responses [17, 18]. Blockade of OX40L inhibits TSLP-driven Th2 inflammatory cell infiltration, cytokine secretion, and IgE production in mouse lung and skin [19]. The receptor for TSLP is a heterodimeric complex composed of TSLPR and IL7Rα chains [20]. The TSLPR chain binds to TSLP at low affinity but its combination with the IL7Rα chain results in high-affinity binding and STAT5 activation [21, 22]. The IL7Rα chain is encoded by IL7R. The nuclear receptors retinoid × receptor (RXR)α and RXRβ act as transcriptional repressors that inhibit TSLP gene expression in mouse skin keratinocyte models of atopic dermatitis [23].

In this study, we report an analysis of association between single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in TSLP, OX40L, IL7R, and RXRα and AR in three independent studies of children with asthma from Costa Rica, North America, and Sweden. We chose to perform this study in children with asthma because AR causes disproportionately high morbidity in children with asthma, and AR is up to four times more prevalent in children with asthma [24]. We found that a SNP in TSLP was associated with reduced odds for AR in boys across the three cohorts of children with asthma.

Methods

Ethics Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from study participants and from parents of children in the cohorts. The institutional review boards of Brigham & Women's Hospital, CAMP Study Centers, and Karolinska Institutet approved the study protocols.

Study Populations

The Genetics of Asthma in Costa Rica

The Genetics of Asthma in Costa Rica study includes 616 children ages 6-14 years with asthma who were recruited between February 2001 and March 2006 [4]. This population is a genetic isolate of mixed Spanish and Amerindian descent with one of the world's highest rates of asthma (27.4% of children aged 6-7 years [25]). Questionnaires were sent to the parents of 13,125 schoolchildren enrolled in 113 schools in Costa Rica. Of the 7,282 children whose parents returned questionnaires, 2,714 had asthma (defined as physician-diagnosed asthma and ≥2 respiratory symptoms or recurrent asthma attacks in the past year). Of these 2,714 children, 616 had high probability of having ≥6 great-grandparents born in the Central Valley of Costa Rica (to ensure descent from the founder population), and were willing to participate along with their parents. Of these 616 parent-child trios, 24 were excluded because of inadequate DNA quality, leaving 592 trios for genotyping and analysis.

Childhood Asthma Management Program (CAMP)

CAMP is a multicenter North American clinical trial designed to investigate the long-term effects of inhaled anti-inflammatory medications in children with mild to moderate asthma [26]. Participating children had asthma defined by symptoms greater than 2 times per week, use of an inhaled bronchodilator at least twice weekly or use of daily medication for asthma, and increased airway responsiveness to methacholine (PC20 ≤ 12.5 mg/ml). Children with severe asthma or other clinically significant medical conditions were excluded. Of the 1041 children enrolled in the original clinical trial, 968 children and 1518 of their parents contributed DNA samples to the CAMP Genetics Ancillary Study [27]. Selection criteria for genome wide association study (GWAS) genotyping were (a) self-described non-Hispanic white ethnicity and (b) availability of sufficient DNA for microarray hybridization; 422 children and their parents met these criteria.

Children, Allergy, Milieu, Stockholm, Epidemiological Survey (BAMSE)

BAMSE is a birth cohort study of allergy and environment. 4089 newborn infants were recruited between 1994 and 1996 from central and northwestern parts of Stockholm, Sweden [28]. At eight years of age, all BAMSE children were invited for clinical testing, and blood samples were obtained from 2,480 children. DNA was extracted from 2,033 samples after exclusion of samples with too little blood, lack of questionnaire data, or if parental consent to genetic analysis of the sample was not obtained. All children with a doctor's diagnosis of asthma ever (n = 251) underwent GWAS genotyping [29].

Phenotyping

Phenotypic data were collected from each participant in Costa Rica at study entry, in CAMP at randomization, and in BAMSE at one, two, four, and eight years of age. AR was defined as naso-ocular symptoms apart from colds in the past 12 months and ≥1 positive skin test reaction (STR) to allergens in Costa Rica and CAMP, and as naso-ocular symptoms in the past 12 months and ≥1 positive allergen-specific IgE (Phadiatop®, Phadia AB, Uppsala, Sweden) at eight years in BAMSE. These definitions for AR are consistent with Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) 2008 guidelines [30]. We chose not to use a physician's diagnosis to define AR given greater variability associated with this definition. We compared allergen-sensitized AR and physician-diagnosed AR in Costa Rica in a previous study [4].

Genotyping

Using data from European Americans (CEU) in the International HapMap project [31], we applied a linkage-disequilibrium (LD)-tagging algorithm (minor allele frequency ≥ 5% and r2 ≥ 0.8) to identify common variation in TSLP, OX40L, IL7R, RXRα and their 10 kb flanks. LD maps were plotted using Haploview [32]. We considered additional SNPs in TSLP to evaluate reported functional variation (rs3806933) [33] and those highlighted in previous studies of asthma (rs1837253) [34]. A total of 21 SNPs were chosen for genotyping in Costa Rican subjects and their parents using the Sequenom iPLEX platform (Sequenom, San Diego, CA) including 9 SNPs for TSLP and 4 SNPs each for OX40L, IL7R, and RXRα. We chose Costa Rica as our population for initial findings because of greater power to detect associations in this cohort relative to CAMP and BAMSE (Table 1). All power calculations were performed using Quanto v.1.2.4. (University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA).

Genome-wide SNP genotyping for CAMP subjects and their parents was performed on Illumina Human-Hap550 Genotyping BeadChip (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA). Genome-wide SNP genotyping for BAMSE subjects was performed on Illumina Human 610-Quad Beadchip (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA). Sixteen of the CAMP GWAS SNPs and fifteen of the BAMSE GWAS SNPs overlapped with those genotyped in Costa Rican subjects and their parents. The 15 overlapping SNPs were used to replicate our initial findings (Table 2). Of these 15 SNPs, 3 were in TSLP (rs1837253, rs2289276, rs17551370), and 4 each were in OX40L (rs1234313, rs10489267, rs10489266, rs1234315), IL7R (rs1494555, rs10063294, rs2194225, rs6897932), and RXRα (rs11185647, rs12339187, rs11185659, rs10881582). The 6 SNPs that were genotyped in Costa Rica but not on both the GWAS platforms had no significant association with AR in Costa Rica. There were no differences in SNP minor allele frequencies between boys and girls in these cohorts.

In all study cohorts, duplicate genotyping was performed on approximately 5% of the sample to assess genotype reproducibility. Genotype quality control was assessed by <1% discordance rate, <5 Mendelian inconsistencies, and genotype completion rates >98% for all loci. All SNPs included in analyses were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p > 0.01).

Of the 592 Costa Rican child-parent trios genotyped, 6 were excluded from this analysis because of Mendelian inconsistencies, leaving 586 trios. Of the 422 nuclear families in CAMP trios, 25 were excluded from this analysis because of Mendelian inconsistencies (n = 6) or missing >5% of the genotypic data (n = 19), leaving 397 families. 12 children from BAMSE were excluded because of duplicate genotyping or non-European ancestry as determined by admixture mapping using principal components analysis [29], leaving 239 children for this analysis.

Statistical Analyses

We tested for association between SNPs in TSLP, OX40L, IL7R, RXRα and AR in children with asthma. Family-based association analyses were first conducted under an additive genetic model in Costa Rican families using the Pedigree-Based Association Test (PBAT) [35] implemented in Helix Tree v6.4.3 (Golden Helix, Bozeman, MT). An advantage of family-based association testing is that it is robust against population stratification and population admixture [36]. We then replicated our findings from Costa Rica in the CAMP and BAMSE cohorts. Family-based analysis using PBAT was performed in CAMP. In BAMSE, associations between SNPs and AR phenotypes were measured using the Cochran-Armitage trend test in PLINK [37]. As we have previously reported sex-specific effects for TSLP on serum total IgE [38] and asthma [11], we also performed sex-stratified analyses in all cohorts. Transmitted to undertransmitted ratios (T:U) and odds ratio estimates for AR phenotypes were obtained using PLINK [37]. To assess for joint evidence of association in the child-based cohorts, P values were combined across Costa Rica, CAMP, and BAMSE with Fisher's combined probability method [39]. Results were considered significant only when consistent associations (i.e. same allele, same direction of genetic effect) were observed in all three populations with a Fisher's combined P value of ≤ 8.0 × 10-4 (0.05/(21*3) to account for multiple testing of 21 SNPs and 3 strata (overall, male, female).

Tests for interaction between SNPs in TSLP, OX40L, IL7R, RXRα were additionally performed using PBAT given high interest in potential gene by gene interactions. Based on our power calculations using Quanto v.1.2.4 for gene by gene interactions, we recognized a priori that our power to detect such interactions would be insufficient. For example, to detect an interaction between two SNPs each with minor allele frequency 0.40 causing a change in risk of 10%, our sample size would have to be 4229 parent-child trios. We therefore limited our interaction testing to the cohort with most subjects (Costa Rica, with 592 trios) and considered this a secondary, exploratory analysis.

Results

The phenotypic characteristics of children in the Costa Rica, Childhood Asthma Management Program (CAMP), and Children, Allergy, Milieu, Stockholm, Epidemiological Survey (BAMSE) study cohorts are shown in Table 3. Consistent with the known gender distribution of asthma in childhood [40], all three cohorts had more boys than girls. Children in Costa Rica had the highest prevalence of AR.

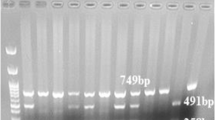

The linkage disequilibrium (LD) patterns and minor allele frequencies (MAF) for the TSLP SNPs genotyped in all three cohorts are shown in Figure 2. There were no major differences in MAFs and LD patterns among the SNPs between the cohorts. The LD patterns and MAFs for the nine TSLP SNPs genotyped in Costa Rica are shown in Figure 3. Consistent with our LD-tagging approach, LD was generally not high between the SNPs chosen for genotyping in Costa Rica.

The results for overall and sex-stratified association testing of TSLP SNP rs1837253 and AR in Costa Rica, CAMP, and BAMSE are shown in Table 4. The association between rs1837253 and AR in all children (in analyses not stratified by sex) was significant in CAMP (P value 0.003) but not in Costa Rica or BAMSE. In sex-stratified analysis, the T allele of SNP rs1837253 was associated with reduced odds for allergen-sensitized AR in boys in all three cohorts, with P values ranging from 0.04 to 0.004. Specifically, the minor allele of rs1837253 was undertransmitted in boys with AR and asthma as compared to boys with asthma alone in all three cohorts. The combined P value across cohorts met our criteria for significance after accounting for multiple testing, with Fisher's combined P value of 1.2 × 10-4. Odds ratios (ORs) for these associations ranged from 0.56 to 0.63. In contrast to the observed results in males, female-specific associations between rs1837253 and AR were inconsistent across cohorts.

The other TSLP SNPs and SNPs in OX40L, IL7R and RXRα were not significantly associated with AR phenotypes across cohorts (Table 5).

Tests for gene by gene interactions showed twelve nominally significant interactions between SNPs in all gene pair combinations of TSLP, OX40L, RXRα and IL7R except for between RXRα and IL7R (Table 6). After accounting for 84 tests for interaction, none remained significant after correction for multiple comparisons (P value threshold for significance 0.05/84 interaction tests = 0.00060).

Discussion

This is the first study to examine genetic associations between SNPs in TSLP and AR. This is also the first study to concurrently examine associations between variants in multiple TSLP-related genes (OX40L, IL7R, RXRα) and AR. We found an inverse male-specific association between the T allele of SNP rs1837253 in TSLP and AR in three independent cohorts of children with asthma. As children with asthma are particularly vulnerable to develop and suffer morbidity from AR, our findings are of direct relevance to this population.

Our study contributes to a nascent literature on the role of TSLP in AR. Prior work on TSLP has focused on other allergic diseases [6, 9–12]. That TSLP could play a role in AR is first suggested by our understanding of TSLP and its ability to drive Th2 dominant inflammation. Second, a limited number of in vitro and murine studies have reported increased TSLP expression in cell cultures and nasal epithelium from AR patients [13–16, 19]. The significant association between a TSLP variant and AR that we observed across multiple large and distinct cohorts supports that TSLP plays a role in AR in humans, corroborates previous in vitro and murine studies, and supports our understanding of TSLP driving allergic inflammation.

We found male-specific associations between TSLP SNP rs1837253 and AR in children with asthma from the Costa Rica, CAMP, and BAMSE studies. This SNP was undertransmitted in boys with AR and asthma as compared to in boys with asthma alone. Although this SNP has previously been associated with asthma [11, 34], the associations with AR that we found cannot be attributed to asthma alone since all subjects in our study had asthma. Our findings suggest an additional role for this SNP in the pathogenesis of AR.

Our results were more statistically significant in boys than in all children, despite reductions in power in the sex-stratified analysis. This suggests that the significant associations among males that we observed across the cohorts were not merely due to the greater number of boys in these cohorts. The gene for the TSLPR chain of the heterodimeric TSLP receptor has a sex chromosome location in humans (Xp22.3 and Yp11.3) [41], and this could partially explain a sex-specific mechanism for TSLP. Sex-dependent hormonal regulation of transcription is also possible. Sex-specific effects have been observed for TSLP[11] and for other genes [42–44].

Our study's findings are consistent with sex-specific epidemiological observations for AR. Male children become more sensitized to environmental allergens and have higher serum total IgE levels [45, 46]. Nasal fluid allergen-specific IgE levels are higher in male than female patients with seasonal AR [47]. A sex-stratified analysis of inflammatory pathways using allergen-challenged CD4+ cells from AR patients showed higher expression signatures in males [47]. Sexual dimorphism has also been noted in genetic linkage and association studies of serum total IgE [38, 48]. Our findings expand on previous reports of sexual dimorphism in allergic disease by identifying sex-specific effects of a genetic variant on AR.

Our laboratory previously reported a sex-specific association between rs2289276 and serum total IgE [38], and between rs1827253 and asthma [11]. rs2289276 is predicted to affect an exonic splicing enhancer, while rs1837253 is thought to disrupt a transcription factor binding site [49]. SNP rs1837253 is located 5.7 kb upstream of the TSLP transcription start site. A study by Harada et al. conducted in human bronchial epithelial suggested that a SNP in the TSLP promoter region could serve as a binding site for transcription activating protein (AP)-1, enhance AP-1 binding to regulatory elements, and lead to TSLP's downstream effects [33]. Harada et al. implicated rs3806933 as the functional SNP; they did not study rs1837253, and rs1837253 is not in LD with rs3806933 (Figure 3). We did not find an association between rs3806933 and AR, nor between rs2289276 and AR. He et al. reported associations between rs1837253 and protection from asthma, atopic asthma, and airway hyperresponsiveness [34], and Hunninghake et al. reported sex-specific associations between rs1837253 and protection from asthma in boys. These studies corroborate rs1837253 as a SNP of interest with a potential functional role.

Recognizing that TSLP interacts with other proteins to affect Th2-driven inflammation, we implemented a comprehensive approach from the outset by also examining for genetic associations between AR and SNPs in OX40L, IL7R, and RXRα. We did not observe findings that were consistent across cohorts for individual SNP associations with AR. This may have been due to unexamined gene-by-environment interactions. Shamim et al. previously reported an association between two IL7R SNPs and inhalation allergy [50]. They did not perform replication analyses in independent populations, and we did not find associations between those SNPs and AR in our cohorts. It is thought that RXRα and RXRβ can influence transcription of TSLP, but neither has been previously studied in subjects with AR [23]. The RXRα SNPs we chose to genotype capture 96% of the HapMap SNPs with MAF ≥ 10% in RXRα and its 10 kb flanks in the CEU population with r2 ≥ 0.8, so our lack of findings for RXRα was unlikely due to inadequate genotypic coverage [32]. Interestingly, our tests for gene by gene interaction among TSLP, OX40L, RXRa and IL7R in Costa Rican subjects demonstrated nominally significant results between SNPs in all gene pairs, except for between RXRα and IL7R. Lack of gene by gene interaction between RXRα and IL7R would be biologically consistent with their physically disparate roles as transcriptional regulator of TSLP and receptor for TSLP, respectively. Further gene by gene analyses with larger sample size could overcome the power limitations we faced.

Our study has additional limitations. First, our findings do not elucidate a specific mechanism. SNP rs1837253 is not in LD with other HapMap SNPs and has the potential to represent a functional SNP itself. Our work provides a specific direction for functional studies that could focus on transcriptional regulators of TSLP. Second, some of our findings in Costa Ricans may be mainly applicable to them and certain Hispanic subgroups. However, we replicated our main finding in CAMP and BAMSE, and previous findings in Costa Rica have been applicable to children of other ethnicities [51, 52]. Family-based testing is also robust against population stratification and population admixture [36]. Lastly, we focused on AR in children with asthma, and it is possible that distinct associations could be found if we examined cohorts with AR only. However, our findings are relevant to a group of children at high risk for AR.

Conclusions

In summary, we found that the T allele of TSLP SNP rs1837253 was associated with reduced odds for AR in three independent cohorts of children with asthma. The association was sex-specific, as it was significant in males but not females. Our work highlights that TSLP likely plays a role in the pathogenesis of AR in children with asthma.

References

Meltzer EO, Blaiss MS, Derebery MJ, Mahr TA, Gordon BR, Sheth KK, Simmons AL, Wingertzahn MA, Boyle JM: Burden of allergic rhinitis: results from the Pediatric Allergies in America survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009, 124: S43-70. 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.05.013

Thomas M, Kocevar VS, Zhang Q, Yin DD, Price D: Asthma-related health care resource use among asthmatic children with and without concomitant allergic rhinitis. Pediatrics. 2005, 115: 129-134.

Sazonov Kocevar V, Thomas J, Jonsson L, Valovirta E, Kristensen F, Yin DD, Bisgaard H: Association between allergic rhinitis and hospital resource use among asthmatic children in Norway. Allergy. 2005, 60: 338-342. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00712.x

Bunyavanich S, Soto-Quiros ME, Avila L, Laskey D, Senter JM, Celedon JC: Risk factors for allergic rhinitis in Costa Rican children with asthma. Allergy. 2010, 65 (2): 256-63. Epub 2009 Oct 1. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02159.x

Corren J, Manning BE, Thompson SF, Hennessy S, Strom BL: Rhinitis therapy and the prevention of hospital care for asthma: a case-control study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004, 113: 415-419. 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.11.034

Soumelis V, Reche PA, Kanzler H, Yuan W, Edward G, Homey B, Gilliet M, Ho S, Antonenko S, Lauerma A: Human epithelial cells trigger dendritic cell mediated allergic inflammation by producing TSLP. Nat Immunol. 2002, 3: 673-680. 10.1038/nrm910

Allakhverdi Z, Comeau MR, Jessup HK, Yoon BR, Brewer A, Chartier S, Paquette N, Ziegler SF, Sarfati M, Delespesse G: Thymic stromal lymphopoietin is released by human epithelial cells in response to microbes, trauma, or inflammation and potently activates mast cells. J Exp Med. 2007, 204: 253-258. 10.1084/jem.20062211

Liu YJ: TSLP in epithelial cell and dendritic cell cross talk. Adv Immunol. 2009, 101: 1-25. full_text

Ying S, O'Connor B, Ratoff J, Meng Q, Mallett K, Cousins D, Robinson D, Zhang G, Zhao J, Lee TH, Corrigan C: Thymic stromal lymphopoietin expression is increased in asthmatic airways and correlates with expression of Th2-attracting chemokines and disease severity. J Immunol. 2005, 174: 8183-8190.

Ying S, O'Connor B, Ratoff J, Meng Q, Fang C, Cousins D, Zhang G, Gu S, Gao Z, Shamji B: Expression and cellular provenance of thymic stromal lymphopoietin and chemokines in patients with severe asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Immunol. 2008, 181: 2790-2798.

Hunninghake GM, Soto-Quiros ME, Avila L, Kim HP, Lasky-Su J, Rafaels N, Ruczinski I, Beaty TH, Mathias RA, Barnes KC: TSLP polymorphisms are associated with asthma in a sex-specific fashion. Allergy. 2010, 65 (12): 1566-75. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02415.x

Rothenberg ME, Spergel JM, Sherrill JD, Annaiah K, Martin LJ, Cianferoni A, Gober L, Kim C, Glessner J, Frackelton E: Common variants at 5q22 associate with pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Nat Genet. 2010, 42: 289-291. 10.1038/ng.547

Mou Z, Xia J, Tan Y, Wang X, Zhang Y, Zhou B, Li H, Han D: Overexpression of thymic stromal lymphopoietin in allergic rhinitis. Acta Otolaryngol. 2008, 1-5.

Miyata M, Hatsushika K, Ando T, Shimokawa N, Ohnuma Y, Katoh R, Suto H, Ogawa H, Masuyama K, Nakao A: Mast cell regulation of epithelial TSLP expression plays an important role in the development of allergic rhinitis. Eur J Immunol. 2008, 38: 1487-1492. 10.1002/eji.200737809

Kamekura R, Kojima T, Koizumi JI, Ogasawara N, Kurose M, Go M, Harimaya A, Murata M, Tanaka S, Chiba H: Thymic stromal lymphopoietin enhances tight-junction barrier function of human nasal epithelial cells. Cell Tissue Res. 2009, 338 (2): 283-93. Epub 2009 Sep 9. 10.1007/s00441-009-0855-1

Zhu DD, Zhu XW, Jiang XD, Dong Z: Thymic stromal lymphopoietin expression is increased in nasal epithelial cells of patients with mugwort pollen sensitive-seasonal allergic rhinitis. Chin Med J (Engl). 2009, 122: 2303-2307.

Ito T, Wang YH, Duramad O, Hori T, Delespesse GJ, Watanabe N, Qin FX, Yao Z, Cao W, Liu YJ: TSLP-activated dendritic cells induce an inflammatory T helper type 2 cell response through OX40 ligand. J Exp Med. 2005, 202: 1213-1223. 10.1084/jem.20051135

Wang YH, Liu YJ: Thymic stromal lymphopoietin, OX40-ligand, and interleukin-25 in allergic responses. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009, 39: 798-806. 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03241.x

Seshasayee D, Lee WP, Zhou M, Shu J, Suto E, Zhang J, Diehl L, Austin CD, Meng YG, Tan M: In vivo blockade of OX40 ligand inhibits thymic stromal lymphopoietin driven atopic inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2007, 117: 3868-3878. 10.1172/JCI33559

Reche PA, Soumelis V, Gorman DM, Clifford T, Liu M, Travis M, Zurawski SM, Johnston J, Liu YJ, Spits H: Human thymic stromal lymphopoietin preferentially stimulates myeloid cells. J Immunol. 2001, 167: 336-343.

Pandey A, Ozaki K, Baumann H, Levin SD, Puel A, Farr AG, Ziegler SF, Leonard WJ, Lodish HF: Cloning of a receptor subunit required for signaling by thymic stromal lymphopoietin. Nat Immunol. 2000, 1: 59-64.

Park LS, Martin U, Garka K, Gliniak B, Di Santo JP, Muller W, Largaespada DA, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Farr AG: Cloning of the murine thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) receptor: Formation of a functional heteromeric complex requires interleukin 7 receptor. J Exp Med. 2000, 192: 659-670. 10.1084/jem.192.5.659

Li M, Messaddeq N, Teletin M, Pasquali JL, Metzger D, Chambon P: Retinoid × receptor ablation in adult mouse keratinocytes generates an atopic dermatitis triggered by thymic stromal lymphopoietin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005, 102: 14795-14800. 10.1073/pnas.0507385102

Meltzer EO, Szwarcberg J, Pill MW: Allergic rhinitis, asthma, and rhinosinusitis: diseases of the integrated airway. J Manag Care Pharm. 2004, 10: 310-317.

Pearce N, Ait-Khaled N, Beasley R, Mallol J, Keil U, Mitchell E, Robertson C: Worldwide trends in the prevalence of asthma symptoms: phase III of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC). Thorax. 2007, 62: 758-766. 10.1136/thx.2006.070169

The Childhood Asthma Management Program (CAMP): design, rationale, and methods. Childhood Asthma Management Program Research Group. Control Clin Trials. 1999, 20: 91-120.

Himes BE, Hunninghake GM, Baurley JW, Rafaels NM, Sleiman P, Strachan DP, Wilk JB, Willis-Owen SA, Klanderman B, Lasky-Su J: Genome-wide association analysis identifies PDE4D as an asthma-susceptibility gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2009, 84: 581-593. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.04.006

Melen E, Nyberg F, Lindgren CM, Berglind N, Zucchelli M, Nordling E, Hallberg J, Svartengren M, Morgenstern R, Kere J: Interactions between glutathione S-transferase P1, tumor necrosis factor, and traffic-related air pollution for development of childhood allergic disease. Environ Health Perspect. 2008, 116: 1077-1084. 10.1289/ehp.11117

Moffatt M, Gut IG, Demenais F, Strachan DP, Bouzigon E, Heath S, von Mutius E, Farrall M, Lathrop M, Cookson WOCM, : A large-scale, consortium-based genome-wide association study of asthma. N Engl J Med. 2010, 363: 1211-1221. 10.1056/NEJMoa0906312

Bousquet J, Khaltaev N, Cruz AA, Denburg J, Fokkens WJ, Togias A, Zuberbier T, Baena-Cagnani CE, Canonica GW, van Weel C, World Health Organization; GA(2)LEN; AllerGen : Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) 2008 update (in collaboration with the World Health Organization, GA(2)LEN and AllerGen). Allergy. 2008, 63: 8-160. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01620.x

The International HapMap Project. Nature. 2003, 426: 789-796.

Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ: Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005, 21: 263-265. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457

Harada M, Hirota T, Jodo AI, Doi S, Kameda M, Fujita K, Miyatake A, Enomoto T, Noguchi E, Yoshihara S: Functional analysis of the thymic stromal lymphopoietin variants in human bronchial epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009, 40: 368-374. 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0041OC

He JQ, Hallstrand TS, Knight D, Chan-Yeung M, Sandford A, Tripp B, Zamar D, Bosse Y, Kozyrskyj AL, James A: A thymic stromal lymphopoietin gene variant is associated with asthma and airway hyperresponsiveness. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009, 124: 222-229. 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.04.018

Lange C, DeMeo D, Silverman EK, Weiss ST, Laird NM: PBAT: tools for family-based association studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2004, 74: 367-369. 10.1086/381563

Laird NM, Lange C: Family-based designs in the age of large-scale gene-association studies. Nat Rev Genet. 2006, 7: 385-394. 10.1038/nrg1839

Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PI, Daly MJ, Sham PC: PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007, 81: 559-575. 10.1086/519795

Hunninghake GM, Lasky-Su J, Soto-Quiros ME, Avila L, Liang C, Lake SL, Hudson TJ, Spesny M, Fournier E, Sylvia JS: Sex-stratified linkage analysis identifies a female-specific locus for IgE to cockroach in Costa Ricans. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008, 177: 830-836. 10.1164/rccm.200711-1697OC

Fisher RA: Statistical Methods for Research Workers. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd; 1932.

Almqvist C, Worm M, Leynaert B: Impact of gender on asthma in childhood and adolescence: a GA2LEN review. Allergy. 2008, 63: 47-57.

Maglott D, Ostell J, Pruitt KD, Tatusova T: Entrez Gene: gene-centered information at NCBI. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35: D26-31. 10.1093/nar/gkl993

Patsopoulos NA, Tatsioni A, Ioannidis JP: Claims of sex differences: an empirical assessment in genetic associations. JAMA. 2007, 298: 880-893. 10.1001/jama.298.8.880

Raby BA, Lazarus R, Silverman EK, Lake S, Lange C, Wjst M, Weiss ST: Association of vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms with childhood and adult asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004, 170: 1057-1065. 10.1164/rccm.200404-447OC

Karjalainen J, Nieminen MM, Aromaa A, Klaukka T, Hurme M: The IL-1beta genotype carries asthma susceptibility only in men. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002, 109: 514-516. 10.1067/mai.2002.121948

Guilbert TW, Morgan WJ, Zeiger RS, Bacharier LB, Boehmer SJ, Krawiec M, Larsen G, Lemanske RF, Liu A, Mauger DT: Atopic characteristics of children with recurrent wheezing at high risk for the development of childhood asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004, 114: 1282-1287. 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.09.020

Uekert SJ, Akan G, Evans MD, Li Z, Roberg K, Tisler C, Dasilva D, Anderson E, Gangnon R, Allen DB: Sex-related differences in immune development and the expression of atopy in early childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006, 118: 1375-1381. 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.09.008

Barrenas F, Andersson B, Cardell LO, Langston M, Mobini R, Perkins A, Soini J, Stahl A, Benson M: Gender differences in inflammatory proteins and pathways in seasonal allergic rhinitis. Cytokine. 2008, 42: 325-329. 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.03.004

Raby BA, Soto-Quiros ME, Avila L, Lake SL, Murphy A, Liang C, Fournier E, Spesny M, Sylvia JS, Verner A: Sex-specific linkage to total serum immunoglobulin E in families of children with asthma in Costa Rica. Hum Mol Genet. 2007, 16: 243-253. 10.1093/hmg/ddl447

Conde L, Vaquerizas JM, Dopazo H, Arbiza L, Reumers J, Rousseau F, Schymkowitz J, Dopazo J: PupaSuite: finding functional single nucleotide polymorphisms for large-scale genotyping purposes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34: W621-625. 10.1093/nar/gkl071

Shamim Z, Muller K, Svejgaard A, Poulsen LK, Bodtger U, Ryder LP: Association between genetic polymorphisms in the human interleukin-7 receptor alpha-chain and inhalation allergy. Int J Immunogenet. 2007, 34: 149-151. 10.1111/j.1744-313X.2007.00657.x

Hersh CP, Raby BA, Soto-Quiros ME, Murphy AJ, Avila L, Lasky-Su J, Sylvia JS, Klanderman BJ, Lange C, Weiss ST, Celedon JC: Comprehensive testing of positionally cloned asthma genes in two populations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007, 176: 849-857. 10.1164/rccm.200704-592OC

Hunninghake GM, Soto-Quiros ME, Avila L, Su J, Murphy A, Demeo DL, Ly NP, Liang C, Sylvia JS, Klanderman BJ: Polymorphisms in IL13, total IgE, eosinophilia, and asthma exacerbations in childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007, 120: 84-90. 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.04.032

Acknowledgements

We thank all subjects for their participation in the Genetics of Asthma in Costa Rica, CAMP, and BAMSE studies. We acknowledge the CAMP investigators and research team, supported by NHLBI, for collection of CAMP Genetic Ancillary Study data. All work on data collected from the CAMP Genetic Ancillary Study was conducted at the Channing Laboratory of the Brigham and Women's Hospital under appropriate CAMP policies and human subject's protections. This work was supported by the National Institute of Health [Grants R37 HL66289, U01 HL075419, P01 HL083069, T32 HL007427]; the Swedish Research Council; Stockholm County Council; Centre for Allergy Research, Karolinska Institutet; Swedish Heart Lung Foundation; Swedish Fulbright Commission; Riksbankens Jubileumsfond; Erik Rönnberg Scholarship; GABRIEL contract number 018996 under Integrated Program LSH-2004-1.2.5-1; the Wellcome Trust [WT084703MA].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

SB contributed to the study design, analyzing the data, and writing the manuscript. EM contributed to analyzing the data and manuscript editing. JBW contributed to analyzing the data and manuscript editing. MG contributed to analyzing the data and manuscript editing. MS contributed to patient recruitment and manuscript editing. LA contributed to patient recruitment and manuscript editing. JLS contributed to analyzing the data and manuscript editing. GH contributed to the study design and manuscript editing. MW contributed to patient recruitment and manuscript editing. GP contributed to patient recruitment and manuscript editing. GTO contributed to patient recruitment and manuscript editing. SW contributed to patient recruitment and manuscript editing. JCC contributed to the study design, patient recruitment and writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Bunyavanich, S., Melen, E., Wilk, J.B. et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) is associated with allergic rhinitis in children with asthma. Clin Mol Allergy 9, 1 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-7961-9-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-7961-9-1