Abstract

Left ventricular hypertrophy is an important risk factor in cardiovascular disease and echocardiography has been widely used for diagnosis. Although an adequate methodologic standardization exists currently, differences in measurement and interpreting data is present in most of the older clinical studies. Variability in border limits criteria, left ventricular mass formulas, body size indexing and other adjustments affects the comparability among these studies and may influence both the clinical and epidemiologic use of echocardiography in the investigation of the left ventricular structure. We are going to review the most common measures that have been employed in left ventricular hypertrophy evaluation in the light of some recent population based echocardiographic studies, intending to show that echocardiography will remain a relatively inexpensive and accurate tool diagnostic tool.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The diagnosis of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) has been incorporated in the clinical practice as an important marker of cardiovascular disease. Its prevalence depends on classification criteria and specific population characteristics, ranging from 3% in normotensive community-based samples [1] to about three-quarters of hypertensive patients [2]. Irrespective of other risk factors, those in the upper distribution of left ventricular mass have their risk at least duplicated for future cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, as summarized in one metanalysis [3].

Echocardiography has been clinically employed for more than 30 years, becoming one of the most important non-invasive imaging methods in the evaluation of cardiac morphology and dynamics. However, the apparent simplicity in LVH evaluation by echocardiography conceals several intrinsic and usually unrecognized critical steps that may limit its clinical validity.

This manuscript introduces the basic principles of left ventricular mass (LV mass) estimation by echocardiography, focusing on the potential limitations and discrepancies of such measurement, in order to provide the appropriate background for understanding the rather complex issue of defining the cut-off values for LVH diagnosis in populations. Although advances in echocardiographic techniques has minimized the impact of many of the methodological details discussed here, an understanding of these topics is important, since most of the clinical and epidemiologic studies currently published are based on the echocardiographic criteria here described. We also intend to give a critical evaluation of the diagnostic performance and clinical validation of this imaging method.

Left Ventricular Measurement

Left ventricular mass is generally calculated as the difference between the epicardium delimited volume and the left ventricular chamber volume multiplied by an estimate of myocardial density. Following this principle, several methodologies have been used to calculate left ventricular mass and to define hypertrophy with its own flaws and strengths on each step (Table 1), resulting in a wide range of values. Probably, the most significant echocardiographic limitation is related to inadequate quality imaging. Population-based studies are not able to obtain complete imaging in almost a quarter of screened patients [4, 5]. mainly due to inappropriate acoustic windows.

Imaging – Mode and Acquisition

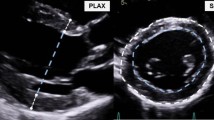

Both M-mode and two-dimensional imaging can be employed to calculate left ventricular mass. M-mode imaging allows better endocardial border definition as it has greater resolution due to higher frame-rate, as long as adequate ultrasound beam positioning is ensured and ventricle shape approaches normality. Two-dimensional imaging, on the other hand, depicts the "real" ventricular shape and identifies regional motion abnormalities. However, the quality of two-dimensional imaging may be limited due to both lower lateral resolution and frame-rate. Additionally this option is more time consuming, limiting its use in epidemiological studies. Two-dimensional images are usually acquired both in paraesternal and apical views, depending on the geometrical formulas that are used.

Technological advances have joined both methods and partially minimized their limitations There are standardized and validated recommendations for the clinical use of two-dimensional determination of LV mass [6], However, two-dimensionally oriented M-mode, obtaining images perpendicularly from the longitudinal axis slightly above the papillary muscle level is widely employed in clinical practice and is accepted as an adequate alternative in epidemiological studies. Digital imaging has also made it possible to reconstruct diverse M-mode planes from two-dimensional images (so called anatomical M-mode), allowing better positioning, although the final image resolution is that of two-dimensional images. Although accurate [7], LV mass estimation using anatomical M-mode has not been adequately validated in clinical studies. Two-dimensional mode has also improved due to refined imaging processing technology, particularly second harmonic imaging. Also, built-in software for automatic border detection has been developed allowing calculation of real-time volumes. Although most of these newer technologies are widely available in commercially available ultrasound equipment, their potential for providing additional accuracy in the evaluation of LVH remains poorly characterized.

A relevant degree of variability in LV mass determination could be attributed to online measurement inaccuracies due to lower imaging resolution of older equipment, which could reach 10% of parietal thickness. Nowadays, variability due to on-line or off-line analysis of digitalized images calculations is of considerably smaller magnitude [8].

We will focus our discussion on M-mode estimation of LV mass, since most epidemiological reports use this imaging modality. Preference for M-mode is based on its technical feasibility and availability at the time when most studies were performed. However, despite adequate correlation with two-dimensional measurements [9], M-mode has been suggested to averagely underestimate LV mass in about 20 g [10]. Theoretically, two-dimensional imaging would be more adequate in samples of patients with cardiovascular disease, where LV shape assumptions play a critical role in LV mass estimation.

Estimating Left Ventricular Volume

Determination of left ventricular volumes is accomplished using formulas that fit ventricular shape to primary geometric figures. Ellipse, cylinder, cone, and truncated polyhedrons have been employed and validated in normally shaped ventricles, although most studies have limited sample sizes [11]. Some geometrical assumptions are best fit using two-dimensional images while others can be performed assuming geometric forms from M-mode imaging.

If a two-dimensional approach is used, both area-length and truncated-ellipsoid models are feasible and reasonably accurate, with validated formulas [6]. Among other formulas for volume calculation, the modified Simpson's Discs Rule, which is greatly facilitated nowadays by built-in software, offers flexibility that allows accurate estimation of left ventricular volumes even in greatly distorted ventricles. Even though volumes determined by Simpson's Rule are frequently used for ventricular function determination, they are not routinely used to calculate LV mass, probably due to limitations resulting from poor epicardial delimitation in some patients. Other geometrical models have been proposed in the past [12, 13], with variable use in clinical practice.

The method of cubed formulas, which incorporate only one dimension of the left ventricular cavity and assume an ellipsoid geometry, is the most widely used to calculate left ventricular volumes and mass in noninvasive laboratories worldwide. The broad acceptance of M-mode derived estimation relies on the fact that it was the first method that was validated and also on its technical simplicity. The one-dimensional approach, however, imposes more strict geometrical assumptions and amplifies the risk of inaccuracy, as measurement errors are cubed.

Defining Border Limits – Conventions of Layer Measurements

Ultrasound signals are reinforced where surfaces change density, allowing definition of limits between surface layers. The inclusion or exclusion of these echoes from interfaces of the left ventricular cavity or myocardial wall can cause significant discrepancies in the overall measurements [14]. Initial M-mode standard recommended inclusion of the edges as part of interventricular septum thickness, but exclusion of the posterior wall epicardial edge [15]. Investigators of the University of Pennsylvania developed a criteria (The Penn Convention) in which all edges are not included in parietal thickness measurements, but are considered as part of the ventricle cavity [16]. This approach underestimate LV mass when compared to the M-mode convention, proposed by the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE). This latter convention (ASE) is the most accepted border definition criteria, becoming the standard recommendation for M-mode estimations, and uses the leading edge of each layer [17](Figure 1). Employing Penn and ASE convention with the same volume formulas may originate LV mass discrepancies in the range of 15% in men and 18% in women [18]. Measurement convention must be acknowledged and adequately corrected for in comparisons of clinical studies of LVH.

Comparison between M-mode border measurement conventions. The Standard convention measures from leading to trailing edge in the septum and from leading to leading edge of the posterior wall. Penn criteria excludes echoes from parietal walls while ASE criteria measure leading to leading edge. (LVDd: Left Ventricular Diameter in Diastole).

In the past few years, spatial resolution of transthoracic echocardiography has greatly enhanced, leading to major improvements in image quality. Most of this progress can be attributed to second harmonic imaging, that significantly increases signal-to-noise ratio by receiving only harmonic frequencies. Although this technology is now widely available in most ultrasound equipment, its potential accuracy to evaluate LVH remains poorly characterized. A recent study suggests that LV mass estimations using second harmonic imaging can cause as much as a 26% increment in mean LV mass index corrected for body surface area, when compared to standard fundamental imaging using similar formulas and conventions [19]. This is probably due to an increase in border refringency.

Calculating Mass (Left Ventricular Mass Formulas)

The most commonly used formulas to estimate LV mass are all variations of the same mathematical principle, based in the volume formulas stated above. Original calculations from Troy and coworkers were the first to be recommended as standard to estimate LV mass from M-mode measurements (Formula 1) [15].

Formula 1: LV mass(Troy) = 1.05 ([LVIDD + PWTD + IVSTD] 3 - [LVIDD] 3 ) g.

Where: LVIDD = Left Ventricular Internal Diameter in Diastole

PWTD = Posterior Wall Thickness in Diastole

IVSTD = Interventricular Septum Thickness in Diastole

Subsequently, Devereux and colleagues suggested a slightly modified regression equation, using the Penn convention as the border definition criteria (Formula 2). Their prediction equation in this pivotal study was derived from necropsy findings of 34 patients [16].

Formula 2: LV mass(Penn) = 1.04 ([LVIDD + PWTD + IVSTD] 3 - [LVIDD] 3 ) -13,6 g.

As depicted above, each regression equation was derived based on a specific border limits convention, an issue that is source of great confusion when interpreting different studies [20]. As expected, LV mass calculations derived from both formulas are linearly correlated, but final crude estimations may differ by more than 20%. Devereux and colleagues proposed a new adjusted equation, validated on necropsy findings of 52 individuals [21], using the ASE convention and accounting for this discrepancy (Formula 3).

Formula3: LVmass(ASE): 0.8 (1.04 ([LVIDD + PWTD + IVSTD] 3 - [LVIDD] 3 ))+ 0,6 g.

Some critical aspects must be acknowledged regarding LV mass formulas. First, all necropsy validation studies have limited sample sizes and evaluate heterogeneous ventricular configurations. Second, these formulas may not perform adequately in distorted ventricles, where a two-dimensional approach is preferred. Different formulas may yield distinct cut point values, as demonstrated by Levy and coworkers in the Framingham cohort [18]. Finally, other post-mortem study showed only moderate correlation between echocardiographic and autopsy LV mass estimations (correlation coefficients ranging from 0.58 to 0.67) [22].

Indexing for Body Size

Both body size and body habitus are clearly associated with LV dimensions and mass. Diverse normalization and indexes were created and tested to adjust for three different sources of physiologic variation in LV mass: lean body mass, obesity, and gender. However, the interdependence of such associations should be carefully understood to allow an adequate correction of LV mass without distorting its association with cardiovascular disease.

Several indexes for body size correction have been proposed, such as height, diverse allometric height adjustments, weight, body surface area, body mass index, and free-fat mass. The best way for normalization of LV mass is still controversial and another source of confusion. Different body-size adjustment criteria and their standard cut points result in different prevalence of patients with LVH [18]. Not surprisingly, those with higher LV mass are more frequently classified as hypertrophic by different classifications simultaneously [23].

The body surface area correction, using the Dubois formula [24], reduces variability due to body size and gender [25], but this index underestimates LV mass in the upper range of the body surface area distribution [26]. A correction based on height alone would allow evaluation of the separate role of obesity in LVH as proposed by Levy and coworkers [18].

Adjustment of LV mass with body surface area would imply that obese patients are expected to have higher LV mass estimations per se. In this scenario, height-based adjustments can more accurately estimate LV mass and the resulting cardiovascular risk associated with LVH in the obese. This turns to be particularly relevant in risk stratification due to the frequent clustering of hypertension, obesity and LHV. Different allometric height-based adjustments have been used. Height2.7, derived from regression models in normal samples from De Simone and coworkers [26], appears to offer the most accurate estimation of LV hypertrophy and risk factors for pathologic changes in the heart structure, particularly in obese subjects. Zoccali and colleagues found LVH indexed by height2.7 to be a better predictor of cardiovascular events than LVH indexed using body surface area in a group of patients under dialysis [27]. Liao and colleagues [28] studied 988 patients and identified progressive increments in death rates with both body surface area and with height2.7 indexing criteria. Subjects simultaneously classified as LVH with body surface area and height2.7 criteria had increased average LV mass and a 3-fold increase in death rates, while those classified as LVH only when indexed by height indexes had no increase in future cardiovascular events. In summary, it appears prudent to favor indexes that do not adjust for obesity, such as height, and height2.7, particularly in studies in which the independent impact of obesity is in question. Body surface area indexing permits adequate classification of most of patients in clinical practice, incorporating in LVH determination some of the risk associated with obesity.

Finally, men have increased LV mass and at least part of this effect can be attributed to body size differences. Gender differences in LV mass are first noticed around puberty and can be minimized although not eliminated by adequate indexing of body size [29]. Due to this difference in LV mass, some criteria for body size adjustments use gender-specific cut points for normality as will be seen below.

Determining Cut-off Points

The determination of cut points in biological variables to define abnormality is frequently a source of controversy, and can be driven by different strategies. The definition of what constitutes an abnormal LV mass is no exception to this rule.

Left Ventricular hypertrophy diagnosis defined by deviation from mean

LV mass as most biological variables are statistically distributed in normal or skewed curves. One can consider the diagnosis of LV hypertrophy in those who are in the extreme right tail of a "Gaussian" distribution, such as beyond two standard deviations of a reference sample of normal individuals. Identification of a "normal representative sample" is not trivial and most studies use relatively small samples. In the late 80s, Levy and coworkers. [18] published a landmark paper evaluating a subset of individuals without known cardiovascular risk factors in the Framingham Cohort. These authors calculated LV mass both with the ASE convention and Troy equation (Formula 1) and with the Penn Convention and Devereux equation (Formula 2) to estimate LV mass, and proposed normal limits for LV mass for men and women, based on cut points at two standard deviations above the mean and using several indexes for body size correction (Table 2). These criteria are widely used in clinical practice and research, despite limitations in representativeness, as they may not perform well in non-white populations.

Left Ventricular hypertrophy defined by prediction of clinical disease

Increase in LV mass has been shown to be an independent prognostic factor for intermediate endpoints [30] and clinical outcomes such as major cardiovascular events and mortality [31, 32]., total mortality [27, 28, 33] and sudden death [34]. However, the risk associated with increases in several "physiological" variables is mostly linear over a great range of variation. This behavior has already been suggested for blood pressure [35] and cholesterol levels [36], leading to aggressive management strategies ("the lower the better"). In fact, Levy and colleagues demonstrated a progressive increase in risk associated to LV mass, even at levels not considered as "hypertrophic". Cardiovascular disease and death rates had a 1.5-fold increase for each 50 g/m of LV mass indexed by height [31]. In a subset of hypertensive patients [32], cardiovascular disease increased monotonically with more than a 4-fold increase in risk between the lowest and highest LV mass quintiles. In this study, clinically relevant increment in risk was identified in patients with LV mass below the limits usually employed for LVH definition.

These findings suggest that traditional cut-off limits may ignore cardiovascular risk associated with increased LV mass in the "normal" range based on statistical assumptions. De Simone and coworkers introduced the concept of inappropriate LV mass increase [37] to use LVH within the context of risk prediction employing multiple factors. It is considered a clinical relevant LV mass increase values above 128% of a predicted LV mass based on gender, estimated stroke volume and height2.7 [38, 39]

Moreover, LVH regression has been used in clinical trials as a favorable prognostic marker. A metanalysis has shown in hypertensive patients that the regression of LVH predicts a reduction of more than 50% in cardiovascular events[40]

Evaluation of Left Ventricular Structure

Alternative concepts to LVH in the determination of left ventricular adaptive processes that take place in the overloaded ventricle assesses the fundamental components used in LV mass estimations, namely wall thickness and diastolic chamber dimension. The expected pathophysiological response of each of these components is theoretically distinct, as pressure overload leads to increased wall thickness and volume overload leads to chamber dilation. These differences cannot be assessed solely by LV mass calculations.

Relative Wall Thickness

Parietal thickness and its relation to LV chamber size have been recognized as measures of hypertrophy for more than 30 years [41]. Relative wall thickness (RWT) is measured in clinical studies both as: 2 * posterior wall thickness divided by LV diastolic diameter or, septal wall thickness + posterior wall thickness divided by LV diastolic diameter. Even thought these measures have been used interchangeably by some investigators, septal asymmetry (IVSTD/PWTD > 1.3) was present in about 5% of Framingham subjects [42] and can lead to an underestimation of relative thickness when only posterior wall thickness is used. The reference cut point value for increased relative wall thickness derived from upper limits of normal samples is usually 0.44 [43] or 0.45 [42], irrespective of which formula is used. RWT provides information regarding LV geometry independent of other calculations [44], precluding the requirement of most corrections. Nevertheless, significant LVH can occur without major changes in RWT, particularly when simultaneous pressure and volume overload are present.

Geometric Patterns

Attempts have been made to evaluate separately adaptive responses in parietal thickness increase and in dilation. Initially, Savage and coworkers [42] stratified Framingham patients with LVH in subgroups as: disproportionate septal LVH; concentric LVH; eccentric-dilated LVH, and eccentric non-dilated LVH. They identified in the 3 last categories increasing levels of systolic blood pressure, utilizing retrospective blood pressure data from 30-years of the cohort follow-up, suggesting a progressive character of adaptive mechanisms. A later approach defined 4 distinct geometric patterns: normal geometry, concentric remodeling, concentric hypertrophy and eccentric hypertrophy (Figure 2). Ganau and coworkers [43], using echocardiographic hemodynamic estimates, reinforced the impression that the geometric patterns parallels progressive hemodynamic changes. Hypertensive target organ disease measured by fundoscopic alterations are also more frequent in hypertrophic geometric patterns [30].

Koren and coworkers [45] used cut points of 125 g/m2 for LVH and 0.45 for RWT in a sample of hypertensive patients and found a 10-year incidence of cardiovascular events of 31% in those with concentric hypertrophy compared to 11% in those with normal geometry. In 1995, two cohorts studies were simultaneously published evaluating geometric patterns impact in the incidence of cardiovascular events. Verdecchia and colleagues [46] studying 694 patients with body surface area indexed LV mass lower than 125 g/m2, without additional adjustment for obesity and other metabolic risk factors, found a relative risk of 2.6 in the 272 patients with concentric remodeling compared to normal geometry patients. Krumholz and coworkers [47], studied 3209 from The Framingham study, indexed LVM by height using cut points of 143 g/m in men and 102 g/m in women and adjusted the models for obesity and other relevant covariates. Their analysis showed a relative risk of 2.1 for all cause mortality with concentric hypertrophy, but not additional risk in those classified as concentric remodeling. Relative risk became nonsignificant when a correction for LV mass was included in the models. Verdecchia and colleagues [48], afterwards could not demonstrate additional risk associated with increased relative wall thickness in those classified as hypertrophic. These data may suggest a smaller independent risk associated with increased wall thickness in hypertensive patients without LVH criteria.

Even though the additional prognostic role of geometric patterns over LVH may be lesser than initially supposed, this classification permits identification of determined adaptive processes. Concentric remodeling may be related to specific pathophysiological adaptations, particularly related to glucose and insulin metabolism [49–51] and studies in contemporary cohorts have also shown an association of concentric forms with diabetes [52, 53].

We believe that geometric classification, with adequate body size indexing and clearly defined standardization, may be an alternative and informative strategy to evaluate adaptive responses, providing information beyond that provided by classification with respect to left ventricular hypertrophy.

Role of additional factors in left ventricular mass and hypertrophy determination

Gender and body size are clearly identified as predictors of LV mass and LVH Definitions are usually corrected and/or stratified for these factors, as seen above. Many others constitutional factors and exposures may lead to changes in LV mass. Some of these factors are pathophysiologically involved in LVH and, moreover, interact among themselves, limiting the interpretation of the independent role of each one.

Gender

Differences in LV mass due to gender, independent of questions related to body size, may have pathophysiological implications. Women have been shown to have an increased parietal hypertrophic responses to pressure overload [54, 55]., even after body size correction. This adaptive pattern was demonstrated also in animal models [56]. The unfavorable prognostic implications of this hypertrophic response are suggested by the findings of Liao and coworkers of a 5-fold greater risk of death associated with LV hypertrophy indexed by BSA in woman compared to the risk associated to LVH in men. However, despite using gender specific cut-offs for LVH, additional adjustment for obesity was not performed. Employment of height2.7 indexing allowed to use a unique cut-point of 51 g/m2.7 for both genders [26], reducing the impact of gender in LVH inference, at least in African-Americans [57].

Obesity

Although the best strategy to adjust LVM for obesity is a matter of debate, obesity is increasingly recognized as an independent predictor of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [58, 59]. The increase in LV mass related to obesity is probably more than a mere physiologic adaptation.

Obesity has been shown to be independently associated to LVH [60], particularly in populations with a high prevalence of hypertension and other metabolic risk factors [61, 62]. Despite this association, the impact of obesity on LVH may be less than expected [63], as Iacobellis and colleagues [64] have demonstrated that "uncomplicated obesity" was not a risk factor for LVH when indexed by either body surface area or height 2.7. As obesity, however, causes complications, it is frequently accompanied by additional risk factors. Adjusting by height 2.7 minimizes the interference of obesity in LV mass estimates (See above: Body-size Indexing).

Age

LV mass progressively increases during aging [65], particularly parietal thickness [4], which was seen in both normotensive and hypertensive patients [66]. Heart size increases during infancy and adolescence due to body size enlargement and, at this stage, the gender differences become prominent [67]. The rate of LV mass increase due to age changes in magnitude [29], weakening its independent role at older individuals, when other risk factors play a greater role [63]. Dannenbeg and coworkers [68] demonstrated that LV mass did not increase with age in a healthy sub-sample of The Framingham study, suggesting that most of the supposed physiological increase is caused by other determinants. These results are reinforced by studies in younger subjects where the age-associated increase in LV mass is partially explained by body size and blood pressure changes [67]. Nevertheless, it appears prudent to adjust for age in epidemiological investigations related to LV mass and hypertrophy.

Ethnicity

LVH is particularly prevalent in African-Americans [5, 62, 69–72]. In these analyses, two particular aspects deserve consideration. An increased crude prevalence of LVH in African-Americans and Hispanics is more evident using height-indexed LV mass than with body surface area-indexed LV mass [71], suggesting that obesity may partially explain the reported ethnic differences. Furthermore, adaptive response to hypertension may differ across ethnic groups. Hypertensive African-Americans, in comparison with hypertensive whites, have increased relative wall thickness, resulting in an increased frequency of concentric remodeling, given equivalent LV mass estimates [72, 73]. However, Afro-American ancestry has been identified as an independent risk factor for LVH [74].

Clinical correlates of left ventricular hypertrophy

Several factors have been shown repeatedly in epidemiologic studies to associate with LVH. Investigation and prognostication based on LVH should take these factors in the account.

Blood Pressure and Hypertension

Numerous population based studies have unequivocally shown an association between hypertension and LVH [4, 5, 65, 75]. Other reports usually stratify their analysis by or restrict to those with hypertension to allow better evaluation of additional risk factors [45, 73, 76, 77]. It is interesting that even within the normal range, increases in blood pressure is related to an increased LV mass [67]. This increment may be attributed to the classical pathophysiological concept of hypertrophic response to increased overload, although neuro-humoral and genetic factors have been also implicated [78]. LVH association with hypertension is so evident that it is recognized as target organ damage in hypertensive disease by several clinical practice guidelines, representing an intermediate unfavorable prognostic marker [79, 80].

Diabetes and The Metabolic Syndrome

Together with obesity and hypertension, diabetes has been implicated as an important determinant of left ventricular mass in most population-based studies [5, 52, 62, 81, 82]. Myocardial and systemic mechanisms, as an increased extra-cellular matrix, vascular hypertrophy and vasoconstriction [83], have been attributed to this hypertrophic response.

An adaptive response has been shown to diverse degrees of altered carbohydrate metabolism, as in Cardiovascular Health Study [82] and in The Strong Heart Study cohort, where diabetes [52], impaired glucose tolerance [84] and insulin levels[85] where associated with increased LV mass. Although associated with an increase in left ventricular mass, hyperinsulinemia [49] and insulin resistance [50] show a stronger association with concentric remodeling. Concentric hypertrophy is more pronounced in diabetes presenting with microalbuminuria [51, 86]., which could imply a progressive adaptive process.

A gender difference in the left ventricular response to diabetes, with an increase in parietal thickening, rather than hypertrophy, being prominent in women has been suggested [81, 85, 87].

LV mass increase is also seen in individuals with other known risk factors, as in those linked to the metabolic syndrome [62, 88]., where pathophysiological aspects related to this syndrome may directly affect ventricular adaptive mechanisms.

Other Risk Factors

A multitude of other factors have been shown to be independently related to LV mass. It should be emphasized that estimates of the relative magnitude of these factors varies according to the degree of adjustment for other known risk factors in statistical modeling. Primary valvular and myocardial disease are clearly related to LV mass increase but will not be subject of our review.

Environmental exposures such as alcohol consumption [89], salt intake [90], smoking [4, 89]. and increased leisure-time physical activity in men [91] have been associated to increased LV mass. Other factors such as blood lipids, pulmonary function, the heart rate and hematocrit have also been implicated but with some inconsistency among different studies [4, 75, 92, 93]. Also, low weight at 1 year-old has been suggested as LV hypertrophy risk factor, concordant with Barker's Theory of the fetal and early life origin of chronic disease[94].

Clinical validity and impact of such factors is controversial, but it may be important to consider them as relevant potential confounders in epidemiological studies investigating the role of novel risk factors in LVH and the role of LVH in disease prediction.

Reproducibility

Each step in LV mass measurement is a potential source of variability. In M-mode measurement, differences of approximately 5% may translate into differences in LV mass between 8% and 15% [95], which can represent about 50 g. This variability can be attributed particularly to the measurement of wall thicknesses and border layer definition [96–98]. Reproducibility is slightly better using the ASE rather than the Penn convention [98]. Additional smaller differences in left ventricular volume determinations can also be attributed to changes in body position or circulatory loading conditions [99].

Intraobserver M-mode measurements may vary about 5% between echocardiographic studies, while interobserver variability may reach 15%. Some trials retesting patients found differences of up to 30 g between tests [100, 101]. When all sources of variability are taken into account, differences in the estimates are not small, since they approach a difference in LV mass values that is associated with a clinically important increased cardiovascular risk. Strategies such as core laboratory reading, strict protocols and regular training may keep this variability in an acceptable range for clinical and epidemiologic studies.

Comparison with other Imaging Methods

Autopsy is classically employed as the gold standard in heart hypertrophy studies, because it objectively measures LV mass. However, use of reported data is complicated by the fact that macroscopic LVH definition criteria are usually more varied than those used in non-invasive testing [102–105], as well as by the fact that different studies have applied different indexing techniques for body size.

From a histological point of view, myocytes hyperplasia is uncommon in adults. Pathologic studies and animal models suggest evaluating hypertrophy suggest that myocytes keep their integrity and functionality until an increase up to 50 -70% above normal [106]. This is concordant with the Linzbach's critical level of LVH, above which cytopathological changes occur with disruption of myocardial tissue integrity and functioning [107].

LV mass can also be calculated from angiography. Although diverse formulas have been employed and validated [13], correlation with echocardiographic calculated LV mass is fair to moderate, with correlation coefficients of between 0.50 and 0.70 [108].

Radioisotopic gated myocardial perfusion imaging with 99mTc-Sestamibi has been employed to estimate LV mass. Its accuracy is limited by image construction and processing variability, resulting in a limited correlation with echocardiographic LV mass [109]. However, Maruyama and coworkers [110] found a good correlation coefficient (r = 0.96) between gated 99mTc-tetrofosmin myocardial perfusion and echocardiographic based LV mass estimations, using an automated quantitative software.

Newer imaging methods have been employed in LV mass determination. Computed tomography has a good correlation with necropsy findings (r = 0.97). In vivo intrareader variability was estimated to be equivalent to 19 g and intereader 28 g [111]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has emerged as a highly reproducible and accurate imaging methodology in the evaluation of LV geometry and mass [112–115]. As a result, it is of great value in evaluating distorted ventricles and its high accuracy may partially counterbalance its costs, due to the smaller samples needed. However, echocardiography costs are considerably lower in most of the countries, there is no significant radiation exposure [116], and just a few-population based studies have used these costly and less available newer imaging techniques.

Real time three-dimensional echocardiography is still experimental, but has incorporated technical advantages in image acquisition and processing. This method may permit accurate real time LV mass measurement without the caveats of geometrical assumptions. Preliminary data suggest that real time three-dimensional echocardiography is at least as accurate and reproducible as MRI calculations [117]. Contrast echo with microbubbles also permits increasing accuracy, particularly in those with inadequate acoustic windows or with distorted ventricles [118].

Conclusion

LV mass estimation and LVH diagnosis role in cardiovascular disease management is based on epidemiological research and also on clinical grounds. Despite more than 30 years of use echocardiography-based LVH calculation and definition are still variable among ultrasound technicians and laboratories around the world, leading to inconsistency among epidemiological studies and possibly limiting its clinical application. Several technical aspects of the echocardiographic exam can generate substantial errors in LV estimations, some of them equivalent in size to those expected to result from pathophysiological processes and therapeutic strategies. Also, adequate indexing for body size seems to be a critical point in defining pathological hypertrophy. LV mass is closely related to the other known cardiovascular risk factors, that must be taken into account concomitantly. Finally, since the risk associated to LV mass appears to be progressive, without a clear threshold, additional input can be added at different baseline risks, defined by the prevalence of other known cardiovascular risk factors. The addition of multiple newer markers, however, leads to a small increment in risk stratification capacity over formulas applying only classical risk factors [119]. Despite these limitations, the role of echocardiography in LV mass determination is of great clinical value.

Considering all the aspects reviewed, use of echocardiography in clinical studies must be standardized applying already defined criteria. In delineating a study, if two-dimensional is impractical, then two-dimensional guided M-mode, using ASE criteria and Devereux modified formula, will allow estimation of LV mass with an acceptable level of accuracy. Additionally, adequate adjustment of related covariates must be undertaken. LHV/Ht2.7greater than 51g/m2.7 appears to be a reliable criteria to define LVH, and the inclusion of a measurement of relative wall thickness, individually or classified as geometric patterns improves the identification of the adaptive mechanisms involved.

Echocardiography is widely available all over the world and major technical improvements have been achieved in the last two decades. Given careful attention with respect to the technical aspects appraised in this review, echocardiography will remain a safe, inexpensive and accurate tool for both the clinical diagnosis and epidemiologic investigation of left ventricular hypertrophy

References

Antoniucci D, Seccareccia F, Menotti A, Dovellini EV, Prati PL, Rovelli F, Fazzini PF: Prevalence and correlates of echocardiographic determined left ventricular hypertrophy in 2318 asymptomatic middle-aged men: the ECCIS project. Epidemiolgia e Clinica della Cardiopatia Ischemica Silente. G Ital Cardiol 1997, 27: 363-369.

Coca A, Gabriel R, de la FM, Lopez-Sendon JL, Fernandez R, Sagastagoitia JD, Garcia JJ, Barajas R: The impact of different echocardiographic diagnostic criteria on the prevalence of left ventricular hypertrophy in essential hypertension: the VITAE study. Ventriculo Izquierdo Tension Arterial Espana. J Hypertens 1999, 17: 1471-1480. 10.1097/00004872-199917100-00016

Vakili BA, Okin PM, Devereux RB: Prognostic implications of left ventricular hypertrophy. Am Heart J 2001, 141: 334-341. 10.1067/mhj.2001.113218

Gardin JM, Arnold A, Gottdiener JS, Wong ND, Fried LP, Klopfenstein HS, O'Leary DH, Tracy R, Kronmal R: Left ventricular mass in the elderly. The Cardiovascular Health Study. Hypertension 1997, 29: 1095-1103.

Skelton TN, Andrew ME, Arnett DK, Burchfiel CM, Garrison RJ, Samdarshi TE, Taylor HA, Hutchinson RG: Echocardiographic left ventricular mass in African-Americans: the Jackson cohort of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Echocardiography 2003, 20: 111-120. 10.1046/j.1540-8175.2003.03000.x

Schiller NB, Shah PM, Crawford M, DeMaria A, Devereux R, Feigenbaum H, Gutgesell H, Reichek N, Sahn D, Schnittger I: Recommendations for quantitation of the left ventricle by two-dimensional echocardiography. American Society of Echocardiography Committee on Standards, Subcommittee on Quantitation of Two-Dimensional Echocardiograms. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 1989, 2: 358-367.

Katsuki K, Nakatani S, Kanzaki H, Hanatani A, Tanaka N, Nakasone I, Masuda Y, Yamagishi M, Miyatake K: [Clinical validation of accuracy of anatomical M-mode measurements: effect of harmonic imaging]. J Cardiol 2001, 37: 35-42.

Arnett DK, Skelton TN, Liebson PR, Benjamin E, Hutchinson RG: Comparison of m-mode echocardiographic left ventricular mass measured using digital and strip chart readings: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2003, 1: 8. 10.1186/1476-7120-1-8

Park SH, Shub C, Nobrega TP, Bailey KR, Seward JB: Two-dimensional echocardiographic calculation of left ventricular mass as recommended by the American Society of Echocardiography: correlation with autopsy and M-mode echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 1996, 9: 119-128.

Paczek A, Gardin JM, Hardin JM, Anton-Culver H, Kurosaki T, Hsu C, Bild DE: Comparison of M-mode and two-dimensional echocardiographic algorithms used to estimate left ventricular mass: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 1995, 8: 780-792.

Vuille C, Weyman A: Left Ventricle I: General Considerations, assessment of chamber size and function. In Principles and Practice of Echocardiography. 2nd edition. Edited by: Weyman A. Malvern, Pennsylvania: Lea & Febinger; 1994:575-624.

Teichholz LE, Kreulen T, Herman MV, Gorlin R: Problems in echocardiographic volume determinations: echocardiographic-angiographic correlations in the presence of absence of asynergy. Am J Cardiol 1976, 37: 7-11. 10.1016/0002-9149(76)90491-4

Tortoledo FA, Quinones MA, Fernandez GC, Waggoner AD, Winters WL Jr: Quantification of left ventricular volumes by two-dimensional echocardiography: a simplified and accurate approach. Circulation 1983, 67: 579-584.

Reichek N: Standardization in the measurement of left ventricular wall mass. M-mode echocardiography. Hypertension 1987, 9: II27-II29.

Troy BL, Pombo J, Rackley CE: Measurement of left ventricular wall thickness and mass by echocardiography. Circulation 1972, 45: 602-611.

Devereux RB, Reichek N: Echocardiographic determination of left ventricular mass in man. Anatomic validation of the method. Circulation 1977, 55: 613-618.

Sahn DJ, DeMaria A, Kisslo J, Weyman A: The committee on M-mode Standardization of the American Society of Echocardiography: recommendations regarding quantitation in M-mode echocardiography: results of a survey of echocardiographic methods. Circulation 1978, 58: 1072-1083.

Levy D, Savage DD, Garrison RJ, Anderson KM, Kannel WB, Castelli WP: Echocardiographic criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy: the Framingham Heart Study. Am J Cardiol 1987, 59: 956-960. 10.1016/0002-9149(87)91133-7

McGavigan AD, Dunn FG, Goodfield NE: Secondary harmonic imaging overestimates left ventricular mass compared to fundamental echocardiography. Eur J Echocardiogr 2003, 4: 178-181. 10.1016/S1525-2167(02)00164-6

Devereux RB: Detection of left ventricular hypertrophy by M-mode echocardiography. Anatomic validation, standardization, and comparison to other methods. Hypertension 1987, 9: II9-II26.

Devereux RB, Alonso DR, Lutas EM, Gottlieb GJ, Campo E, Sachs I, Reichek N: Echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular hypertrophy: comparison to necropsy findings. Am J Cardiol 1986, 57: 450-458. 10.1016/0002-9149(86)90771-X

Bachenberg TC, Shub C, Hauck AJ, Edwards WD: Can anatomical left ventricular mass be estimated reliably by M-mode echocardiography? A clinicopathological study of ninety-three patients. Echocardiography 1991, 8: 9-15.

Wachtell K, Bella JN, Liebson PR, Gerdts E, Dahlof B, Aalto T, Roman MJ, Papademetriou V, Ibsen H, Rokkedal J, et al.: Impact of different partition values on prevalences of left ventricular hypertrophy and concentric geometry in a large hypertensive population : the LIFE study. Hypertension 2000, 35: 6-12.

Dubois D, Dubois EF: A formula to estimate the aproximate surface area if height and weight be known. Arch Intern Med 1916, 17: 863-871.

Devereux RB, Lutas EM, Casale PN, Kligfield P, Eisenberg RR, Hammond IW, Miller DH, Reis G, Alderman MH, Laragh JH: Standardization of M-mode echocardiographic left ventricular anatomic measurements. J Am Coll Cardiol 1984, 4: 1222-1230.

De Simone G, Daniels SR, Devereux RB, Meyer RA, Roman MJ, de Divitiis O, Alderman MH: Left ventricular mass and body size in normotensive children and adults: assessment of allometric relations and impact of overweight. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992, 20: 1251-1260.

Zoccali C, Benedetto FA, Mallamaci F, Tripepi G, Giacone G, Cataliotti A, Seminara G, Stancanelli B, Malatino LS: Prognostic impact of the indexation of left ventricular mass in patients undergoing dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2001, 12: 2768-2774.

Liao Y, Cooper RS, Durazo-Arvizu R, Mensah GA, Ghali JK: Prediction of mortality risk by different methods of indexation for left ventricular mass. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997, 29: 641-647. 10.1016/S0735-1097(96)00552-9

De Simone G, Devereux RB, Daniels SR, Meyer RA: Gender differences in left ventricular growth. Hypertension 1995, 26: 979-983.

Shigematsu Y, Hamada M, Mukai M, Matsuoka H, Sumimoto T, Hiwada K: Clinical evidence for an association between left ventricular geometric adaptation and extracardiac target organ damage in essential hypertension. J Hypertens 1995, 13: 155-160.

Levy D, Garrison RJ, Savage DD, Kannel WB, Castelli WP: Prognostic implications of echocardiographically determined left ventricular mass in the Framingham Heart Study. N Engl J Med 1990, 322: 1561-1566.

Schillaci G, Verdecchia P, Porcellati C, Cuccurullo O, Cosco C, Perticone F: Continuous relation between left ventricular mass and cardiovascular risk in essential hypertension. Hypertension 2000, 35: 580-586.

Verdecchia P, Carini G, Circo A, Dovellini E, Giovannini E, Lombardo M, Solinas P, Gorini M, Maggioni AP: Left ventricular mass and cardiovascular morbidity in essential hypertension: the MAVI study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001, 38: 1829-1835. 10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01663-1

Haider AW, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Levy D: Increased left ventricular mass and hypertrophy are associated with increased risk for sudden death. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998, 32: 1454-1459. 10.1016/S0735-1097(98)00407-0

MacMahon S, Peto R, Cutler J, Collins R, Sorlie P, Neaton J, Abbott R, Godwin J, Dyer A, Stamler J: Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 1, prolonged differences in blood pressure: prospective observational studies corrected for the regression dilutional bias. Lancet 1990, 335: 765-774. 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90878-9

Mortality rates after 10.5 years for participants in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Findings related to a priori hypotheses of the trial. The Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial Research Group JAMA 1990, 263: 1795-1801. 10.1001/jama.263.13.1795

De Simone G, Pasanisi F, Contaldo F: Link of nonhemodynamic factors to hemodynamic determinants of left ventricular hypertrophy. Hypertension 2001, 38: 13-18.

De Simone G, Palmieri V, Koren MJ, Mensah GA, Roman MJ, Devereux RB: Prognostic implications of the compensatory nature of left ventricular mass in arterial hypertension. J Hypertens 2001, 19: 119-125. 10.1097/00004872-200101000-00016

De Simone G, Verdecchia P, Pede S, Gorini M, Maggioni AP: Prognosis of inappropriate left ventricular mass in hypertension: the MAVI Study. Hypertension 2002, 40: 470-476. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000034740.99323.8A

Verdecchia P, Angeli F, Borgioni C, Gattobigio R, De Simone G, Devereux RB, Porcellati C: Changes in cardiovascular risk by reduction of left ventricular mass in hypertension: a meta-analysis. Am J Hypertens 2003, 16: 895-899. 10.1016/S0895-7061(03)01018-5

Sjogren AL: Left ventricular wall thickness determined by ultrasound in 100 subjects without heart disease. Chest 1971, 60: 341-346.

Savage DD, Garrison RJ, Kannel WB, Levy D, Anderson SJ, Stokes J III, Feinleib M, Castelli WP: The spectrum of left ventricular hypertrophy in a general population sample: the Framingham Study. Circulation 1987, 75: I26-I33.

Ganau A, Devereux RB, Roman MJ, De Simone G, Pickering TG, Saba PS, Vargiu P, Simongini I, Laragh JH: Patterns of left ventricular hypertrophy and geometric remodeling in essential hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992, 19: 1550-1558.

Li L, Shigematsu Y, Hamada M, Hiwada K: Relative wall thickness is an independent predictor of left ventricular systolic and diastolic dysfunctions in essential hypertension. Hypertens Res 2001, 24: 493-499. 10.1291/hypres.24.493

Koren MJ, Devereux RB, Casale PN, Savage DD, Laragh JH: Relation of left ventricular mass and geometry to morbidity and mortality in uncomplicated essential hypertension. Ann Intern Med 1991, 114: 345-352.

Verdecchia P, Schillaci G, Borgioni C, Ciucci A, Battistelli M, Bartoccini C, Santucci A, Santucci C, Reboldi G, Porcellati C: Adverse prognostic significance of concentric remodeling of the left ventricle in hypertensive patients with normal left ventricular mass. J Am Coll Cardiol 1995, 25: 871-878. 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00424-O

Krumholz HM, Larson M, Levy D: Prognosis of left ventricular geometric patterns in the Framingham Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 1995, 25: 879-884. 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00473-4

Verdecchia P, Schillaci G, Borgioni C, Ciucci A, Gattobigio R, Zampi I, Santucci A, Santucci C, Reboldi G, Porcellati C: Prognostic value of left ventricular mass and geometry in systemic hypertension with left ventricular hypertrophy. Am J Cardiol 1996, 78: 197-202. 10.1016/S0002-9149(96)90395-1

Ohya Y, Abe I, Fujii K, Ohmori S, Onaka U, Kobayashi K, Fujishima M: Hyperinsulinemia and left ventricular geometry in a work-site population in Japan. Hypertension 1996, 27: 729-734.

Sundstrom J, Lind L, Nystrom N, Zethelius B, Andren B, Hales CN, Lithell HO: Left ventricular concentric remodeling rather than left ventricular hypertrophy is related to the insulin resistance syndrome in elderly men. Circulation 2000, 101: 2595-2600.

Picca M, Agozzino F, Pelosi G: Influence of microalbuminuria on left ventricular geometry and function in hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ital Heart J 2003, 4: 48-52.

Devereux RB, Roman MJ, Paranicas M, O'Grady MJ, Lee ET, Welty TK, Fabsitz RR, Robbins D, Rhoades ER, Howard BV: Impact of diabetes on cardiac structure and function: the strong heart study. Circulation 2000, 101: 2271-2276.

Palmieri V, Bella JN, Arnett DK, Liu JE, Oberman A, Schuck MY, Kitzman DW, Hopkins PN, Morgan D, Rao DC, et al.: Effect of type 2 diabetes mellitus on left ventricular geometry and systolic function in hypertensive subjects: Hypertension Genetic Epidemiology Network (HyperGEN) study. Circulation 2001, 103: 102-107.

Carroll JD, Carroll EP, Feldman T, Ward DM, Lang RM, McGaughey D, Karp RB: Sex-associated differences in left ventricular function in aortic stenosis of the elderly. Circulation 1992, 86: 1099-1107.

Rohde LE, Zhi G, Aranki SF, Beckel NE, Lee RT, Reimold SC: Gender-associated differences in left ventricular geometry in patients with aortic valve disease and effect of distinct overload subsets. Am J Cardiol 1997, 80: 475-480. 10.1016/S0002-9149(97)00398-6

Weinberg EO, Thienelt CD, Katz SE, Bartunek J, Tajima M, Rohrbach S, Douglas PS, Lorell BH: Gender differences in molecular remodeling in pressure overload hypertrophy. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999, 34: 264-273. 10.1016/S0735-1097(99)00165-5

Nunez E, Arnett DK, Benjamin EJ, Liebson PR, Skelton TN, Taylor H, Andrew M: Optimal threshold value for left venticular hypertrophy in blacks: the A therosclerosis risk in communities study. Hypertension 2005, 45: 58-63.

Seidell JC, Visscher TL, Hoogeveen RT: Overweight and obesity in the mortality rate data: current evidence and research issues. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1999, 31: S597-S601. 10.1097/00005768-199911001-00018

Zhou BF: Effect of body mass index on all-cause mortality and incidence of cardiovascular diseases – report for meta-analysis of prospective studies open optimal cut-off points of body mass index in Chinese adults. Biomed Environ Sci 2002, 15: 245-252.

Kuch B, Hense HW, Gneiting B, Doring A, Muscholl M, Brockel U, Schunkert H: Body composition and prevalence of left ventricular hypertrophy. Circulation 2000, 102: 405-410.

Kuperstein R, Hanly P, Niroumand M, Sasson Z: The importance of age and obesity on the relation between diabetes and left ventricular mass. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001, 37: 1957-1962. 10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01242-6

De Simone G, Palmieri V, Bella JN, Celentano A, Hong Y, Oberman A, Kitzman DW, Hopkins PN, Arnett DK, Devereux RB: Association of left ventricular hypertrophy with metabolic risk factors: the HyperGEN study. J Hypertens 2002, 20: 323-331. 10.1097/00004872-200202000-00024

Gardin JM, Siscovick D, Anton-Culver H, Lynch JC, Smith VE, Klopfenstein HS, Bommer WJ, Fried L, O'Leary D, Manolio TA: Sex, age, and disease affect echocardiographic left ventricular mass and systolic function in the free-living elderly. The Cardiovascular Health Study. Circulation 1995, 91: 1739-1748.

Iacobellis G, Ribaudo MC, Leto G, Zappaterreno A, Vecci E, Di Mario U, Leonetti F: Influence of excess fat on cardiac morphology and function: study in uncomplicated obesity. Obes Res 2002, 10: 767-773.

Levy D: Echocardiographically detected left ventricular hypertrophy: prevalence and risk factors. The Framingham Heart Study. Ann Intern Med 1988, 108: 7-13.

De Simone G, Daniels SR, Kimball TR, Roman MJ, Romano C, Chinali M, Galderisi M, Devereux RB: Evaluation of concentric left ventricular geometry in humans: evidence for age-related systematic underestimation. Hypertension 2005, 45: 64-68.

Burke GL ARCWWLCYBG: Blood pressure and echocardiographic measures in children: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Circulation 1987, 75: 106-114.

Dannenberg AL, Levy D, Garrison RJ: Impact of age on echocardiographic left ventricular mass in a healthy population (the Framingham Study). Am J Cardiol 1989, 64: 1066-1068. 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90816-3

Arnett DK, Rautaharju P, Crow R, Folsom AR, Ekelund LG, Hutchinson R, Tyroler HA, Heiss G: Black-white differences in electrocardiographic left ventricular mass and its association with blood pressure (the ARIC study). Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities. Am J Cardiol 1994, 74: 247-252. 10.1016/0002-9149(94)90365-4

Koren MJ, Mensah GA, Blake J, Laragh JH, Devereux RB: Comparison of left ventricular mass and geometry in black and white patients with essential hypertension. Am J Hypertens 1993, 6: 815-823.

Zabalgoitia M, Ur Rahman SN, Haley WE, Oneschuk L, Yunis C, Lucas C, Yarows S, Krause L, Amerena J: Impact of ethnicity on left ventricular mass and relative wall thickness in essential hypertension. Am J Cardiol 1998, 81: 412-417. 10.1016/S0002-9149(97)00925-9

Liebson PR, Grandits G, Prineas R, Dianzumba S, Flack JM, Cutler JA, Grimm R, Stamler J: Echocardiographic correlates of left ventricular structure among 844 mildly hypertensive men and women in the Treatment of Mild Hypertension Study (TOMHS). Circulation 1993, 87: 476-486.

Chaturvedi N, Athanassopoulos G, McKeigue PM, Marmot MG, Nihoyannopoulos P: Echocardiographic measures of left ventricular structure and their relation with rest and ambulatory blood pressure in blacks and whites in the United Kingdom. J Am Coll Cardiol 1994, 24: 1499-1505.

Kizer JR, Arnett DK, Bella JN, Paranicas M, Rao DC, Province MA, Oberman A, Kitzman DW, Hopkins PN, Liu JE, et al.: Differences in left ventricular structure between black and white hypertensive adults: the Hypertension Genetic Epidemiology Network study. Hypertension 2004, 43: 1182-1188. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000128738.94190.9f

Gardin JM, Wagenknecht LE, Anton-Culver H, Flack J, Gidding S, Kurosaki T, Wong ND, Manolio TA: Relationship of cardiovascular risk factors to echocardiographic left ventricular mass in healthy young black and white adult men and women. The CARDIA Study. Circulation 1995, 92: 380-387.

Gottdiener JS, Reda DJ, Materson BJ, Massie BM, Notargiacomo A, Hamburger RJ, Williams DW, Henderson WG: Importance of obesity, race and age to the cardiac structural and functional effects of hypertension. The Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Antihypertensive Agents. J Am Coll Cardiol 1994, 24: 1492-1498.

De Simone G, Devereux RB, Roman MJ, Alderman MH, Laragh JH: Relation of obesity and gender to left ventricular hypertrophy in normotensive and hypertensive adults. Hypertension 1994, 23: 600-606.

Lips DJ, deWindt LJ, van Kraaij DJ, Doevendans PA: Molecular determinants of myocardial hypertrophy and failure: alternative pathways for beneficial and maladaptive hypertrophy. Eur Heart J 2003, 24: 883-896. 10.1016/S0195-668X(02)00829-1

Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT Jr, et al.: The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA 2003, 289: 2560-2572. 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560

2003 European Society of Hypertension-European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension J Hypertens 2003, 21: 1011-1053. 10.1097/00004872-200306000-00001

Galderisi M, Anderson KM, Wilson PWF, Levy D: Echocardiographic evidence for a existence of a distinct cardiomyopathy (The Framingham Heart Study). Am J Cardiol 1991, 68: 85-89. 10.1016/0002-9149(91)90716-X

Lee M, Gardin JM, Lynch JC, Smith V-E, Tracy RP, Savage PJ, Szklo M, Ward BJ: Diabetes mellitus and echocardiographic left ventricular function in free-living elderly men and women: The Cardiovascular Health Study. Am Heart J 1997, 133: 36-43.

Feener EP, King GL: Vascular dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. Lancet 1997,350(Suppl 1):SI9-13.

Ilercil A, Devereux RB, Roman MJ, Paranicas M, O'Grady MJ, Welty TK, Robbins DC, Fabsitz RR, Howard BV, Lee ET: Relationship of impaired glucose tolerance to left ventricular structure and function: The Strong Heart Study. Am Heart J 2001, 141: 992-998. 10.1067/mhj.2001.115302

Ilercil A, Devereux RB, Roman MJ, Paranicas M, O'Grady MJ, Lee ET, Welty TK, Fabsitz RR, Howard BV: Associations of insulin levels with left ventricular structure and function in American Indians: the strong heart study. Diabetes 2002, 51: 1543-1547.

Wachtell K, Palmieri V, Olsen MH, Bella JN, Aalto T, Dahlof B, Gerdts E, Wright JT Jr, Papademetriou V, Mogensen CE, et al.: Urine albumin/creatinine ratio and echocardiographic left ventricular structure and function in hypertensive patients with electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy: the LIFE study. Losartan Intervention for Endpoint Reduction. Am Heart J 2002, 143: 319-326. 10.1067/mhj.2002.119895

Rutter MK, Parise H, Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Larson MG, Meigs JB, Nesto RW, Wilson PW, Vasan RS: Impact of glucose intolerance and insulin resistance on cardiac structure and function: sex-related differences in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2003, 107: 448-454. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000045671.62860.98

Chinali M, Devereux RB, Howard BV, Roman MJ, Bella JN, Liu JE, Resnick HE, Lee ET, Best LG, De Simone G: Comparison of cardiac structure and function in American Indians with and without the metabolic syndrome (the Strong Heart Study). Am J Cardiol 2004, 93: 40-44. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.09.009

Manolio TA, Levy D: Relation of alcohol intake to left ventricular mass: The Framingham Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 1991, 17: 717-721.

Schmieder RE, Messerli FH, Garavaglia GE, Nunez BD: Dietary salt intake. A determinant of cardiac involvement in essential hypertension. Circulation 1988, 78: 951-956.

Savage DD, Levy D, Dannenberg AL, Garrison RJ, Castelli WP: Association of echocardiographic left ventricular mass with body size, blood pressure and physical activity (the Framingham Study). Am J Cardiol 1990, 65: 371-376. 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90304-J

Jullien V, Gosse P, Ansoborlo P, Lemetayer P, Clementy J: Relationship between left ventricular mass and serum cholesterol level in the untreated hypertensive. J Hypertens 1998, 16: 1043-1047. 10.1097/00004872-199816070-00019

Bella JN, Devereux RB, Roman MJ, O'Grady MJ, Welty TK, Lee ET, Fabsitz RR, Howard BV: Relations of left ventricular mass to fat-free and adipose body mass: the strong heart study. The Strong Heart Study Investigators. Circulation 1998, 98: 2538-2544.

Vijayakumar M: Birth weight, weight at one year, and left ventricular mass in adult life. Br Heart J 1995, 73: 363-367.

Stollberger C, Hollander I, Dimitrov L, Slany J: Influence of measurement inaccuracies on determination of left ventricular mass by M mode echocardiography. Heart 1996, 75: 312-313.

de Leonardis V, Cinelli P: Evidence of no interobserver variability in M-mode echocardiography. Clin Cardiol 1986, 9: 324-326.

Collins HW, Kronenberg MW, Byrd BF III: Reproducibility of left ventricular mass measurements by two-dimensional and M-mode echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol 1989, 14: 672-676.

Fast JH: Limits of reproducibility of left ventricular wall thickness and mass by M-mode echocardiography. Neth J Med 1989, 34: 297-301.

Lantelme P, Bouchayer D, Gayet C, Lievre M, Gessek J, Milon H: Influence of a rapid change of left ventricular dimensions on the echocardiographic measurement of left ventricular mass by the Penn convention. J Hypertens 1999, 17: 1323-1328. 10.1097/00004872-199917090-00013

Palmieri V, Dahlof B, DeQuattro V, Sharpe N, Bella JN, De Simone G, Paranicas M, Fishman D, Devereux RB: Reliability of echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular structure and function: the PRESERVE study. Prospective Randomized Study Evaluating Regression of Ventricular Enlargement. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999, 34: 1625-1632. 10.1016/S0735-1097(99)00396-4

De Simone G, Muiesan ML, Ganau A, Longhini C, Verdecchia P, Palmieri V, Agabiti-Rosei E, Mancia G: Reliability and limitations of echocardiographic measurement of left ventricular mass for risk stratification and follow-up in single patients: the RES trial. Working Group on Heart and Hypertension of the Italian Society of Hypertension. Reliability of M-mode Echocardiographic Studies. J Hypertens 1999, 17: 1955-1963. 10.1097/00004872-199917121-00027

Dadgar SK, Tyagi SP, Singh RP, Hameed S: Factors influencing the normal heart weight – a study of 140 hearts. Jpn Circ J 1979, 43: 77-82.

Hangartner JR, Marley NJ, Whitehead A, Thomas AC, Davies MJ: The assessment of cardiac hypertrophy at autopsy. Histopathology 1985, 9: 1295-1306.

Murphy ML, White HJ, Meade J, Straub KD: The relationship between hypertrophy and dilatation in the postmortem heart. Clin Cardiol 1988, 11: 297-302.

de la Grandmaison GL, Clairand I, Durigon M: Organ weight in 684 adult autopsies: new tables for a Caucasoid population. Forensic Sci Int 2001, 119: 149-154. 10.1016/S0379-0738(00)00401-1

Broughton A, Korner PI: Left ventricular pump function in renal hypertensive dogs with cardiac hypertrophy. Am J Physiol 1986, 251: H1260-H1266.

Linzbach AJ: Hypertrophy, hyperplasia and structural dilatation of the human heart. Adv Cardiol 1976, 18: 1-14.

Hradec J, Aschermann M, Vancura J, Petrasek J, Drechslerova J, Michaljanic A, Jezek V: Comparison of M-mode echocardiography and angiography in the evaluation of left ventricular hypertrophy. Cor Vasa 1986, 28: 341-349.

Williams KA, Lang RM, Reba RC, Taillon LA: Comparison of technetium-99m sestamibi-gated tomographic perfusion imaging with echocardiography and electrocardiography for determination of left ventricular mass. Am J Cardiol 1996, 77: 750-755. 10.1016/S0002-9149(97)89211-9

Maruyama K, Hasegawa S, Nakatani D, Paul AK, Kusuoka H, Nishimura T, Hori M, Hatazawa J: Left ventricular mass index measured by quantitative gated myocardial SPECT with 99mTc-tetrofosmin: a comparison with echocardiography. Ann Nucl Med 2003, 17: 31-39.

Mousseaux E, Beygui F, Fornes P, Chatellier G, Hagege A, Desnos M, Lecomte D, Gaux JC: Determination of left ventricular mass with electron beam computed tomography in deformed, hypertrophic human hearts. Eur Heart J 1994, 15: 832-841.

Missouris CG, Forbat SM, Singer DR, Markandu ND, Underwood R, MacGregor GA: Echocardiography overestimates left ventricular mass: a comparative study with magnetic resonance imaging in patients with hypertension. J Hypertens 1996, 14: 1005-1010.

Pons LG, Carreras F, Borras X, Llauger J, Palmer J: [Comparative study of echocardiography and magnetic resonance imaging in the assessment of left ventricular mass]. Rev Esp Cardiol 2001, 54: 22-28.

Grothues F, Smith GC, Moon JC, Bellenger NG, Collins P, Klein HU, Pennell DJ: Comparison of interstudy reproducibility of cardiovascular magnetic resonance with two-dimensional echocardiography in normal subjects and in patients with heart failure or left ventricular hypertrophy. Am J Cardiol 2002, 90: 29-34. 10.1016/S0002-9149(02)02381-0

Bottini PB, Carr AA, Prisant LM, Flickinger FW, Allison JD, Gottdiener JS: Magnetic resonance imaging compared to echocardiography to assess left ventricular mass in the hypertensive patient. Am J Hypertens 1995, 8: 221-228. 10.1016/0895-7061(94)00178-E

Picano E: Economic and biological costs of cardiac imaging. Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2005, 3: 13. 10.1186/1476-7120-3-13

Chuang ML, Beaudin RA, Riley MF, Mooney MG, Mannin WJ, Douglas PS, Hibberd MG: Three-dimensional echocardiographic measurement of left ventricular mass: comparison with magnetic resonance imaging and two-dimensional echocardiographic determinations in man. Int J Card Imaging 2000, 16: 347-357. 10.1023/A:1026540809758

Thomson HL, Basmadjian AJ, Rainbird AJ, Razavi M, Avierinos JF, Pellikka PA, Bailey KR, Breen JF, Enriquez-Sarano M: Contrast echocardiography improves the accuracy and reproducibility of left ventricular remodeling measurements: a prospective, randomly assigned, blinded study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001, 38: 867-875. 10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01416-4

Folsom AR, Chambless LE, Duncan BB, Gilbert AC, Pankow JS: Prediction of coronary heart disease in middle-aged adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003, 26: 2777-2784.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work, read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Foppa, M., Duncan, B.B. & Rohde, L.E. Echocardiography-based left ventricular mass estimation. How should we define hypertrophy?. Cardiovasc Ultrasound 3, 17 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-7120-3-17

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-7120-3-17