Abstract

Background

Available data on the effects of a fermented soy product enriched with Enterococcus faecium and Lactobacillus Jugurti on circulating lipids and adiposity are not completely settled. This study aimed to observe the effects of a fermented soy product enriched with Enterococcus faecium and Lactobacillus Jugurti on central obesity and dyslipidemia control in Wistar adult male rats.

Methods

Over a period of 8 weeks, animals had "ad libitum" food intake and water consumption as well as body weight and food consumption was monitored. The animals were assigned to four different experimental groups: Control Group (C); Control + Fermented Product Group (CPF); Hypercholesterolemic diet group (H); and Hypercholesterolemic + Fermented Product Group (HPF). The HPF and CPF groups received an intragastric administration of 1 ml of fermented product daily. After the experimental period the animals were killed by decapitation, blood was collected to measure cholesterol, triglycerides and HDL-cholesterol plasma concentration. Adipocyte circumference, lipolysis and lipogenis rates were measures using epididymal and retroperitoneal white adipose tissues.

Results

The results demonstrated that 1 ml/day/rat of the fermented soy product promoted important benefits such as reduced cholesterolemia in hypercholesterolemic diet group and the adipocyte circumference in both control and hypercholesterolemic diet group.

Conclusion

The fermented soy product enriched with Enterococcus faecium and Lactobacillus Jugurti decreased circulating lipids levels and reduced adipocyte area in rats.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The term probiotic refers to live micro-organisms which when administered in adequate amounts confer a health benefit on the host [1]. Probiotic bacteria have been the focus of much scientific and commercial interest due to a range of possible health effects of these bacteria such as on lipid metabolism [2, 3]. The most widely studied probiotic bacteria were Lactobacillus GG, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium bifidum and Enterococcus faecium [2–4].

Probiotic dairy products are considered to have functional properties because the probiotic bacteria added to the regular fermentation cultures provide therapeutic benefits such as modification of the immune system, reduction in cholesterol, alleviation from lactose intolerance and faster relief from diarrhea [5].

Available data on the effects of probiotic bacteria on lipid metabolism are controversial. It has been reported that Lactobacillus acidophilus [6] or Streptococcus faecalis [7] had hypocholesterolemic functions and the cholesterol-lowering mechanism depends heavily on binding of dietary cholesterol by Lactobacillus acidophilus or Streptococcus faecalis. Zacconi et al. [8] shown that Enterococcus faecium had a higher hypocholesterolemic effect in axenic mice than Lactobacillus acidophilus. In another study, L. acidophilus and a probiotic mixture decreased serum cholesterol concentration of rats fed with fat-and cholesterol-enriched diet while the Streptococcus faecalis failed to promote this effect [9]. On the other hand, in mice fed with control diet [10] and in rats fed with hypertriglyceridemic diet [11] the L. acidophilus had no effect on plasma cholesterol level. In a normocholesterolemic women and men, fermented milk with a bacteria culture containing Enterococcus faecium promoted a rapid reduction of LDL-cholesterol, but during a long-term intake (6 month) the reduction of LDL-cholesterol was similar to the placebo product [12].

Nowadays the soybean is another alimentary source that gets attention from the scientific community. Several studies have been shown that the soy protein, with or without dietary cholesterol, lowers plasma cholesterol and triacylglycerol concentrations in rats [13–15]. In contrast, Moundras et al. [16] reported that when rats were fed soybean protein at a suboptimal level (13%), serum cholesterol concentration was significantly higher than that in rats fed with 13% casein diet, and this higher cholesterol level was counteracted by supplementation of the diet with 0.4% methionine.

Some studies in human subjects have shown a significant hypocholesterolemic effect of soy protein in hypercholesterolemic subjects [17–20]. However, the hypocholesterolemic effect of soy protein also has been shown to be minimal or negligible in normocholesterolemic subjects [21, 22]. In addition, it has been reported that the soy protein versus the casein diet can reduce body fat and serum insulin levels in rats [23].

Manzoni et al. [24], reported that the soy product fermented by Enterococcus faecium and Lactobacillus Jugurti supplemented with isoflavones had beneficial effects on white adipose tissue in juvenile male rats, leads to a decrease in adipocyte size. However, the consequences of Enterococcus faecium and soy protein intake on circulating lipids and adiposity area are not completely settled. In this sense, the purpose of the present study was to examine the effect of ferment soy product enriched with Enterococcus faecium and Lactobacillus Jugurti in rats fed with control diet or hypercholesterolemic diet on circulating lipids levels and adipocyte area.

Results

Percentage of Body Weight Gain and Total Food Intake

The results of body weight and food intake are shown in Table 1. The percentage of body weight gain and total food intake were increased in H group as compared to the C and HPF groups. No significant differences in the percentage of body weight and total food intake were observed among C, CPF, and HPF groups.

Retroperitoneal and Epididymal adipose tissues

Table 2 shows that there were no significant differences between C and CPF groups when RET (absolute and relative) and EPI (relative) weight as compared. In the HPF group the RET and EPI (absolute and relative) weight were lower than in H group.

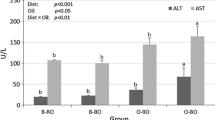

A significant reduction was observed in RET and EPI adipocyte circumference when CPF and HPF were compared with C and H groups (Table 3 and Figure 1 and 2).

Circumference (μm) of the adipocyte from Retroperitoneal (RET) White Adipose Tissue in rats fed different diets during 8 weeks. Values are means ± SEM (n = 8). A – Control Group (C): circumference = 127.35 ± 2.49 μm. B – Control + Fermented Product Group (CPF): circumference = 118.06 ± 1.75* μm. C – Hypercholesterolemic Diet Group (H): circumference = 138.59 ± 2.37+ μm. D – Hypercholesterolemic + Fermented Product Group (HPF): circumference = 113.49 ± 2.03* μm. *p < 0.05 comparing C × CPF and H × HPF; +p < 0.05 comparing C × H.

Circumference (μm) of the adipocyte from Epididymal (EPI) White Adipose Tissue in rats fed different diets during 8 weeks. Values are means ± SEM (n = 8). A – Control Group (C): circumference = 128.25 ± 2.05 μm. B – Control + Fermented Product Group (CPF): circumference = 110.13 ± 1.42* μm. C – Hypercholesterolemic Diet Group (H): circumference = 122.69 ± 1.73 μm. D – Hypercholesterolemic + Fermented Product Group (HPF): circumference = 110.12 ± 1.42* μm. *p < 0.05 comparing C × CPF and H × HPF.

Measurements of the lipogenesis and lipolysis rate

The fermented soy product treatments significantly decreased lipogenesis rate in RET, EPI and Liver when H and HPF were compared. In CPF group, it was observed that RET and EPI lipogenesis rates were decreased when compared with C group, however, no significant differences were observed in liver lipogenesis rate (Table 4).

We observed a significant increase in lipolysis rate (RET and EPI) in the HPF group when compared with H. When C and CPF groups were compared it was observed an increase only in RET lipolysis rate (Table 5).

Plasma lipids

A significant TC and plasma TG is noted higher in comparing the H (108.67 ± 5.22; 177.83 ± 15.78) to the C Group (62.17 ± 3.07; 122.67 ± 15.08). Rats treated with hypercholesterolemic diet plus fermented product (HPF) presented a significant reduction of circulating cholesterol and triglyceride levels as compared to hypercholesterolemic diet group (Table 6).

Fermented soy product in HPF group tended to an increase (p = 0,08) in HDL-cholesterol concentration compared with H group. However, the difference was only significant when C group was compared with CPF group (Table 6).

Discussion

In the present study, feeding rats with hypercholesterolemic diet resulted in a significant increase in food intake and body weight gain. On the other hand, previous reports did not show a difference significantly in food intake of rats fed chow diet and hypercholesterolemic diet [24–27]. Probably this could be accounted by the difference of the period of treatment and the amount of cholesterol present in the diet, since in our study the period of treatment was longer and the concentration of cholesterol was lower than made by the others [24–27]. In spite of that, the diet used in the present study was able to promote hypercholesterolemia and increase plasma triglycerides around 45% in rats, without modify HDL-cholesterol concentration.

This study demonstrated that a cholesterol-rich diet can significantly increase body weight gain, probably because of the increased food intake, which can cause dyslipidemia and obesity because of the additional cholesterol in its properties [28]. Several animal and human studies have confirmed the hypercholesterolemic properties of a cholesterol diet, which include increasing TC, TG, and alterations in the lipoprotein pattern, however, the mechanisms of which remain under study [28–30].

In rats, the mechanisms that prevent dyslipidemia are due to the reduction of the feedback inhibition of cholesterol biosynthesis and increased bile acid excretion, leading to a minor elevation of serum cholesterol after a cholesterol-enriched diet. [31]. However, cholic acid addition to the diet caused an increase in plasma total cholesterol levels, since cholic acid promotes cholesterol absorption [28] which was clearly shown in our study.

Fermented soy product administration resulted in a decrease in food intake and body weight gain in hypercholesterolemics rats, whereby the obtained values were similar in the control group that received or not the fermented soy product. Besides was observed a weight reduction of the white adipose tissue in hypercholesterolemic rats treated with fermented soy product. Previous study have found that the relative EPI weight in rats fed the cholesterol-enriched diet and a chow diet plus fermented soy product, tended to be lower than those in rats fed the chow diet or a cholesterol-enriched diet [24].

Our results showed a significant reduction in the circumference of EPI and RET depots when the ferment soy product enriched with Enterococcus faecium and Lactobacillus Jugurti was used, probably due to the significantly decrease in lipogenesis rate and increase in lipolysis rate in the RET and EPI, which were clearly shown in this study (H × HPF and C × CPF). Previous work has indicated that soy protein alters hormone balance and in turn accelerates lipid metabolism [21] and suppress hepatic lipogenic enzyme gene expression in Wistar fatty rats [32]. Our results suggested that a small amount of soy protein enriched with Enterococcus faecium and Lactobacillus Jugurti could have the same effect of the previously reported.

Some studies have reported a hypocholesterolemic effect with soy [19, 33, 34], whereas other studies have failed to find this effect [35]. In our study, the treatment with fermented soy product produced a significant lower in plasma cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations in the rats fed a hypercholesterolemic diet. Our results are in agreement with those reported by Rossi et al. [25] and Manzoni et al. [24], however in the last study was used the fermented soy product supplemented with isoflavones. Our results suggest that beyond isoflavone the Enterococcus faecium and Lactobacillus Jugurti can assist in the hypocholesterolemic effect. In most of the studies that reported positive results, was more effective in hypercholesterolemic subjects than in normocholesterolemic subjects [36, 37].

There are multiple mechanisms by which soy protein could modulate plasma lipid and lipoprotein concentrations [37]. The interaction of protein with isoflavones and other non-protein components may contribute to the cholesterol-lowering effect of soy protein, since the isoflavones are structurally similar to estrogen and bind to the estrogen receptor [20, 38]. In previous studies [39–42], reported that isoflavones have no effect when given separately.

Others soy bioactive components such as amino acids, minerals and the phytin acid could be acting actively in the decrease of the cholesterol and triglycerides. Same amino acids as the lysine increase the plasma cholesterol concentration [43], while others as e.g. arginine [44], have opposite action. This fact could partly be an explanation of hypocholesterolemic effects of the soy, as it contains good relation arginine/lysine [45]. The phytin acid present in soy has chelant property for certain minerals, such as for instance zinc. As the soy reduces the zinc absorption, it provides a low relation zinc/copper, which could reduce cholesterol. However, the concentration of these substances was not evaluated in the present study.

It is known that the soy presents some antinutritious factors such as trypsin and chymotrypsin inhibitors, mineral chelants and flatulence factor. Studies consider the possibility that trypsin inhibitors are capable to increase the cholecistochinin secretion that stimulates the liberation and subsequent bile secretion [42, 43]. The soy possesses great fibre amount so this could be as well related to its hypocholesterolemic effects [44]. In addition, as was stated by Kritchevsky [45], animals fed soy protein excrete more neutral and acidic steroids, and have increased activity of hepatic HMG CoA reductase and cholesterol 7alpha-hydroxylase. In fact, Aoyama et al. [14] showed that rats fed soy protein had an increase in fecal-fat excretion.

The addition of the Enterococcus faecium to soy also could contribute to the decrease in cholesterol concentration in the group treated with hypercholesterolemic diet, this effect was possibly due to the ability of the E. faecium to reduce in 54% the cholesterol added to the adequate culture medium [26], it has been proposed that the possible hypocholesterolemic effect of E. faecium involves inhibition of exogenous cholesterol absorption from the diet [24].

Rossi et al. [25], reported that administration of fermented soy product enriched with Enterococcus faecium and Lactobacillus Jugurti 10 ml/day, for 15 days lowered in plasma cholesterol in 18,4%, however this difference disappeared at the 30th day. As was stated by St-Onge et al. [46], the fermented product containing several types of bacteria, with indigestible carbohydrates and that produce short-chain fatty acid that will alter cholesterol synthesis. Also, the intestinal bacteria can bind bile acids to cholesterol, resulting in the excretion of bile acid-cholesterol complexes in the feces. Decreased bile acid recycling through the enterohepatic circulation would result in cholesterol uptake from the circulation into the liver for again synthesis of bile acids.

The fermented soy product use promoted a significant increase in HDL-cholesterol concentration, this is an important factor that determining the reduction in the risk of cardiovascular diseases. Similar results were obtained by Fukushima and Nakano [47] and Rossi [25], who showed that rats fed with high cholesterol diet, had reduction in the total cholesterol and an increase in HDL fraction with a daily intake of a probiotic product containing species of Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, and yeast.

The intake of 200 ml/day of the fermented soy milk, produced with Enterococcus Faecium and Lactobacillus Jugurti, for 6 weeks led to a 10% increase in HDL-cholesterol level in normocholesterolemic middle-age men [48]. Agerholm-Larsen et al. [49], reported that the consumption of yogurt fermented with different probiotics had variable effects on LDL cholesterol in obese subjects. Previous studies that used probiotic mixture containing Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus casei, and Bifidobacterium bifidum, but found no significant effect on body weight, fat deposition, plasma cholesterol levels [50], suggesting that hypolipidemic effect is dependent on the type of probiotics.

In addition, the low serum cholesterol concentrations observed in rats treated with HPF diet as compared to H diets; might be due to the reduction of lipogenesis. Thus, the reduced biosynthesis of fatty acids in turn will reduce the production of VLDL particles, thus limiting the formation of LDL particles and resulting in low serum triglycerides and cholesterol concentrations [51].

Further studies are needed to clarify whether this effect is due to the soy protein or to the Enterococcus faecium and Lactobacillus Jugurti and whether other types of probiotic mixtures containing different bacterial strains, other than used in the present study, have effects on lipid metabolism deserves further investigation.

Conclusion

The present study showed that 1 ml/day/rat of fermented soy product enriched with Enterococcus faecium and Lactobacillus Jugurti induces an improvement in lipid profile and reduction in visceral and central adiposity.

Methods

Animals

Thirty-two adults male Wistar rats, weighing 210 ± 10 g were housed in individual cages. The animals were kept at an environmental temperature of 23 ± 2°C in a 12 h light/dark controlled room. All animal procedures were performed according to principles in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals [52].

Diets

Before beginning the experiment, the animals were submitted during five days to an adaptive period of flavour conditioning: during two days the animals received the sweet solution; afterwards they received during two days the sweet and acid solution, and finally the placebo product. The animals were randomly divided into four groups (n = 8) as follows: Control Group (C); Control + Fermented Product Group (CPF); Hypercholesterolemic diet group (H); and Hypercholesterolemic + Fermented Product Group (HPF). The control groups were fed with a chow diet (Nuvilab®). The animals of the H and HPF groups were fed with a chow diet enriched in cholesterol 0,15% (w/w), of Sigma C 8503 cholesterol. The cholesterol was diluted in ethyl ether P.A and stabilized with 10 ppm of butylated hydroxytoluene-BHT. The HPF and CPF groups received an intragastric administration of 1 ml of fermented product daily, during the 8 weeks of the study. Body weight gain and total food intake was measured.

Preparation of the fermented product

The fermented soy product was prepared according to the methodology described by Rossi et al. (1999), and was added in 1.5% (v/v) of the Enterococcus faecium CRL 183 culture and 1.5% (v/v) of Lactobacillus Jugurti 416 culture. Quantification of the viable cells in the finished fermented product was performed using the specific M 17-agar and MRS-agar media of culture. The colonies formed were counted and their morphological characteristics were recorded [26].

Experimental Procedure

After 8 weeks of treatment the animals were killed by decapitation. Trunk blood was collected in a heparinized tube and was centrifuged for 15 min at 2500 rev./min. Retroperitoneal (RET) and Epididymal (EPI) white adipose tissues were immediately removed and weighed.

Adipocyte size

A fragment (100 mg) of RET and EPI was fixed in 0.2 M collidine buffer pH 7.4, containing 2% of osmium tetroxide at 37°C. After 24 hours, they were washed with warmed saline as described by Hirsch & Gallian (1968). The adipocyte circumference was measured using image analysis software (Image Pro Plus) and expressed as μm.

Plasma lipids

Plasma was used to measure triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol (TC) and HDL-cholesterol. For these measurements we used commercial Kits from Labtest Diagnostic S.A.

Measurements of the lipogenesis rate

All animals were killed by decapitation 1 h after an intraperitoneal injection of 3 mCi 3H2O in a volume of 0.3 ml for the determination of the in vivo lipogenesis rate. The "de novo" lipogenic (fatty acid synthesis) rate was determined by the incorporation of 3H2O into saponified lipids according to the method of Robinson & Williamson [53]. Tissues samples were digested in 3 ml of 30% KOH and 3 ml of ethanol for at least 2 h at 70°C in capped tubes for the lipids to saponify. After cooling, 2 ml of 12 N H2SO4 was added, and lipid was extracted three times with 10 ml of petroleum ether [54]. The combined petroleum ether plus extracts was washed with 2 ml of distilled water and evaporated to dryness. The extracted fatty acids were dissolved in 5 ml of scintillation liquid, and radioactivity of 20 μl serum samples was counted for the determination of specific activity. The rate of lipogenesis was calculated as micromoles of 3H2O incorporated into lipids per gram per hour. The lipid content of the tissue was determined by the gravimetric method [55].

Determination of lipolysis rate "in vitro"

Tissue fragments (about 100 mg) of RET and EPI were used for "in vitro" determination of glycerol release, an index of lipolytic rate [56]. The samples were minced into small fragments and incubated for 1 h at 37°C under continuous shaking in Ca2+-free Krebs-Henseleit solution containing 2% (w/v) bovine albumin (fraction V-essentially fatty acid-free), pH 7.4. Lipolysis was interrupted by placing the vials on ice. The tissue fragments were then removed and the glycerol content in the medium was determined enzymatically by the method of Eggstein and Kreutz [57]. The results were expressed as μmol of glycerol released/h.100 mg of tissue.

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as means ± standard error of the means. Data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA to test the effects of diets, fermented soy product and their interactions, following by Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test. Significance was accepted at the p < 0.05 level.

Abbreviations

- BHT:

-

Butylated hydroxytoluene

- C:

-

Control Group

- CPF:

-

Control + Fermented Product Group

- E.:

-

Enterococcus

- EPI:

-

Epididymal adipose tissue

- H:

-

Hypercholesterolemic diet group

- HDL:

-

High Density Lipoprotein

- L.:

-

Lactobacillus

- LDL:

-

Low Density Lipoprotein

- PF:

-

Fermented Product Group

- RET:

-

Retroperitoneal adipose tissue

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- TG:

-

Triglycerides

- VLDL:

-

Very Low-Density Lipoprotein

References

World Health Organization : Food and Agriculture Organization of the United States (FAO)/World Health Organization (WHO). Joint of FAO/WHO Working Group Report on Drafting Guidelines for the Evaluation of Probiotics in Food, London Ontário, Canadá. 2002, April 30 and May 1.

Klein A, Friedrich U, Vogelsang H, Jahreis G: Lactobacillus acidophilus 74-2 and Bifidobacterium animalis subsp DGCC 420 modulate unspecific cellular immune response in healthy adults. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008, 62 (5): 584-593. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602761

Park YH, Kim JG, Shin YW, Kim HS, Kim YJ, Chun T, Kim SH, Whang KY: Effects of Lactobacillus acidophilus 43121 and a mixture of Lactobacillus casei and Bifidobacterium longum on the serum cholesterol level and fecal sterol excretion in hypercholesterolemia-induced pigs. Biosci Biotechnol Bioche. 2008, 72: 595-600. 10.1271/bbb.70581.

Ross NM, Katan MB: Effects of probiotic bacteria on diarrhea, lipid metabolism, and carcinogenesis: a review of papers published between 1988 and 1998. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000, 71: 405-411.

Hekmat S, Reid G: Sensory properties of yogurt is comparable to standard yogurt. Nutr Res. 2006, 26: 163-166. 10.1016/j.nutres.2006.04.004.

Gilliland SE, Nelson CR, Maxwell C: Assimilation of cholesterol by Lactobacillus acidophilus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985, 49: 377-

Ishihara K, Shin R, Shiina T, Yamamoto H, Isoda M: Influence of intestinal bacteria on cholesterol metabolism. Intestinal flora and bio-homeostasis. Edited by: Mitsuoka T. 1989, 121-Tokyo: Japan Scientific Societies Press.

Zacconi C, Bottazzi V, Rebecchi A, Bosi E, Sarra PG, Tagliaferri L: Serum cholesterol levels in axenic mice colonizeed with Enterococcus faecium and Lactobacillus acidophilus. Microbiologica. 1992, 15 (4): 413-417.

Fukushima M, Yamada A, Tsuyoshi E, Nakano M: Effects of a mixture of organisms, Lactobacillus acidophillus or Streptococcus faecalis on Δ6-desaturase activity in the livers of rats fed with fat- and cholesterol-enriched diet. Nutrition. 1999, 15: 373-378. 10.1016/S0899-9007(99)00030-1

Zhou JS, Shu Q, Rutherfurd KJ, Prasad J, Birtles MJ, Gopal PK, Gill HS: Safety assessment of potencial probiotic lactic acid bacterial strains Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001, Lb. acidophilus HN017, and Bifidobacterium lactis HN019 in BALB/c mice. Int J Food Microbiol. 2000, 56: 87-96. 10.1016/S0168-1605(00)00219-1

Oda T, Hashiba H: Effects of skim milk and its fermented product by Lactobacillus acidophilus on plasma and liver lipid levels in diet-induced hypertriglyceridemic rats. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol. 1994, 40 (6): 617-621.

Richelsen B, Kristensen K, Pedersen SB: Long-term (6 months) effect of a new fermented milk product on the level of plasma lipoproteins a placebo-controlled and double blinde study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1996, 50 (12): 811-815.

Morita T, Oh-Hashi A, Takei K, Ikai M, Kasaoka S, Kiriyama S: Cholesterol lowering effects of soybean, potato and rice proteins depend on their low methionine contents in rats fed a cholesterol-free purified diet. J Nutr. 1997, 127: 470-477.

Aoyama T, Fukuri K, Takamatsu K, Yukio H, Yamamoto T: Soy protein isolate and its hydrolysate reduce body fat of dietary obese rats and genetically obese mice (yellow KK). Nutrition. 2000, 16: 349-354. 10.1016/S0899-9007(00)00230-6

Peluso MR, Winters TA, Shanahan MF, Banz WJ: A cooperative interaction between soy protein and its isoflavones-enriched fraction lowers hepatic lipids in male obese Zucker rats and reduces blood platelet sensitivity in male sprague-Dawley rats. J Nutr. 2000, 130: 2333-2342.

Moundras C, Remesy C, Levrat MA, Demigne C: Methionine deficiency in rats fed soy protein induces hypercholesterolemia and potentiates lipoprotein susceptibility to peroxidation. Metabolism. 1995, 44: 1146-1152. 10.1016/0026-0495(95)90007-1

Gaddi A, Descovich GC, Noseda G: Hypercholesterolemia treated by soy bean protein diet. Arch Dis Child. 1987, 62: 274-278. 10.1136/adc.62.3.274

Widhalm K, Brazda G, Schneider B, Kohl S: Effect of soy protein diet versus standard low fat, low cholesterol diet on lipid and lipoprotein levels in children with familiar or polygenic hypercholesterolemia. J Pediatr. 1993, 123: 30-34. 10.1016/S0022-3476(05)81533-1

Potter SM, Bakhit RM, Essex-Sorlie DL: Depression of plasma cholesterol in men by consuption of baked products containing soy protein. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994, 58: 501-506.

Anthony MS, Clarkson TB, Willians JK: Effects of soy isoflavoines on atherocleroses: potencial mechanisms. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998, 68 (6 Suppl): 1390S-1393S.

Meinertz H, Faergeman O, Nilausen K, Chapman MJ, Goldstein S, Laplaud PM: Effect of soy protein and casein in low cholesterol diets on plasma lipoproteins in normolipidemic subjects. Atherosclerosis. 1988, 72 (1): 63-70. 10.1016/0021-9150(88)90063-9

Meinertz H, Nilausen K, Faergeman O: Soy protein and casein in cholesterol-enriched diets: effects on plasma lipoproteins in normolipidic subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989, 50 (4): 786-793.

Baba N, Radwan H, Itallie TV: Effect of casein versus soy protein diets on body composition and serum lipids levels in adults rats. Nutr Res. 1992, 12: 279-285. 10.1016/S0271-5317(05)80733-X.

Manzoni MSJ, Rossi AE, Carlos IZ, Vendramini RC, Duarte ACGO, Dâmaso AR: Fermented soy product supplemented with isoflavones affected fat depots in juvenile rats. Nutrition. 2005, 21: 1018-1024. 10.1016/j.nut.2005.02.007

Rossi EA, Vendramini RC, Carlos IZ, Ueiji IS, Squinzari MM, Silva I, Valdez GF: Effects of a novel fermented soy product on the serum lipids of hypercholesterolemic rabbits. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2000, 74: 213-216. 10.1590/S0066-782X2000000300003.

Munilla MA, Herrera E: A cholesterol-rich diet causes a greater hypercholesterolemic response in pregnant than in nonpregnant rats and does not modify fetal lipoprotein profile. J Nutr. 1997, 127: 2239-2245.

Yokogoshi H, Mochizuki H, Nanami K, Hida Y, Miyachi F, Oda H: Dietary taurine enhances cholesterol degradation and reduces serum and liver cholesterol concentrations in rats fed a high-cholesterol diet. J Nutr. 1999, 129: 1705-1712.

Guerra RLF, Prado WL, Cheik NC, Viana FP, Botero JP, Vendramini R: Effects of 2 or 5 consecutive exercise days on adipocyte area and lipid parameters in Wistar rats. Lipids Health Dis. 2007, 6: 16- 10.1186/1476-511X-6-16

Naveh E, Werman MJ, Sabo E, Neeman I: Defatted avocado pulp reduces body weight and total hepatic fat but increases plasma cholesterol in male rats fed diets with cholesterol. J Nutr. 2002, 132: 2015-2018.

Zulet MA, Barber A, Garcin H, Higueret P, Martynez JA: Alterations in Carbohydrate and Lipid Metabolism Induced by a Diet Rich in Coconut Oil and Cholesterol in a Rat Model. J Am Coll Nutr. 1999, 18 (1): 36-42.

Lin DS, Connor WE: The long term effects of dietary cholesterol upon the plasma lipids, lipoproteins, cholesterol absorption, and the sterol balance in man: the demonstration of feedback inhibition of cholesterol biosynthesis and increased bile acid excretion. J Lipid Res. 1980, 21: 1042-1052.

Iratani N, Hosomi H, Fukuda H: Soybean protein suppresses hepatic lipogenic enzyme gene expression in Wistar fatty rats. J Nutr. 1996, 126: 380-386.

Kern M, Ellison D, Marroquin Y, Ambrose M, Mosier K: Effects of soy protein supplemented with methionine on blood lipids and adiposity of rats. Nutrition. 2002, 18 (7–8): 654-656. 10.1016/S0899-9007(02)00783-9

Hsu CS, Chiu WC, Yeh SL: Effects of soy isoflavone supplementation on plasma glucose, lipids, and antioxidant enzyme activities in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Nutr Res. 2003, 23 (1): 67-75. 10.1016/S0271-5317(02)00386-X.

Laurin D, Jacques H, Moorjani S: Effects of soy protein beverage on plasma lipoproteins in children with familiar hypercholesterolemia. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991, 54: 98-103.

Sirtori CR, Zucchi-Dentone C, Sirtori M: Cholesterol lowering and HDL raising properties of lecithinated soy proteins in type II hyperlipidemic patients. Ann Nutr Metab. 1985, 29: 348-357. 10.1159/000176991

Bricarello LP, Kasinski N, Bertolami MC, Faludi A, Pinto LA, Relvas WG, Izar MC, Ihara SS, Tufik S, Fonseca FA: Comparison between the effects of soy milk and non-fat cow milk on lipid profile and lipid peroxidation in patients with primary hypercholesterolemia. Nutrition. 2004, 20 (1): 200-204. 10.1016/j.nut.2003.10.005

Anderson JW, Smith BM, Wasnock CS: Cardiovascular and renal benefits of dry bean and soybean intake. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999, 70 (3 Suppl): 464S-474S.

Balmir F, Staack R, Jeffrey E, Jimenez MD, Wang L, Potter SM: An extract of soy flour influences serum cholesterol and thyroid hormones in rats and hamsters. J Nutr. 1996, 126: 3046-3053.

Greaves KA, Parks JS, Williams JK, Wagner JD: Intact dietary soy protein, but not adding an isoflavones-rich soy extract to casein, improves plasma lipids in ovariectomized cynomolgus monkeys. J Nutr. 1999, 129: 1585-1592.

Greaves KA, Wilson MD, Rudel LL, Williams JK, Wagner JD: Consumption of soy protein reduces cholesterol absorption compared to casein protein alone or supplemented with an isoflavones extract or conjugated equine estrogen in ovariectomized cynomolgus monkeys. J Nutr. 2000, 130: 820-826.

Fukui K, Tachibana N, Fukuda Y, Takamatsu K, Sugano M: Ethanol washing does not attenuate the hypocholesterolemic potential of soy protein. Nutrition. 2004, 20 (11–12): 984-990. 10.1016/j.nut.2004.08.011

Friedman M, Brandon DL: Nutritional and health benefits of soy proteins. J Agric Food Chem. 2001, 49: 1069-1086. 10.1021/jf0009246

Mateos-Aparicio I, Redondo Cuenca A, Villanueva-Suárez MJ, Zapata-Revilla MA: Soybean, a promising health source. Nutr Hosp. 2008, 23 (4): 305-12.

Kritchevsky D: Protein and atherosclerosis. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 1990, 36 (Suppl 2): S81-S86.

St-Onge CPS, Farnworth ER, Jones P: Consumption of fermented and non fermented dairy produtcs: effects on cholesterol. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000, 71: 674-681.

Fukushima M, Nakano M: The effect of a probiotic on fecal and liver lipid classes in rats. Br J Nutr. 1995, 73: 701-710. 10.1079/BJN19950074

Rossi EA, Vendramini RC, Carlos IZ, Oliveira MG, Valdez GF: Efeito de um novo produto fermentado de soja sobre os lípides séricos de homens adultos normocolesterolêmicos. ALAN. 2003, 53 (1): 47-51.

Agerholm-Larsen L, Raben A, Haulrik N, Hansen S, Manders M, Astrup A: Effect of 8 week intake of probiotic milk products on risk factors for cardiovascular diseases. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2000, 54 (4): 288-297. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600937

Ascencio C, Torres N, Isoard-Acosta F, Gómez-Pérez FJ, Hernández-Pando R, Tovar AR: Soy Protein Affects Serum Insulin and Hepatic SREBP-1 mRNA and Reduces Fatty Liver in Rats. J Nutr. 2004, 134 (3): 522-529.

Ali AA, Velasquez MT, Hansen CT, Mohamed AI, Bhathena SJ: Effects of soybean isoflavones, probiotics, and their interactions on lipid metabolism and endocrine system in an animal model of obesity and diabetes. J Nutr Biochem. 2004, 15: 583-590. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2004.04.005

, : Guide for care and use of laboratory animals. Revised ed. 1985, 85-23. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences.

Robinson AM, Williamson DH: Control of glucose metabolism in isolated acini of the lactating mammary gland of rat: effects of oleate on glucose utilization and lipogenesis. Biochem J. 1978, 170: 609-621.

Stansbie D, Browsey RW, Crettaz M, Denton RM: Acute effects in vivo of anti-insulin serum on rates of fatty acid synthesis and activities of acetylcoenzyme A carboxylase and pyruvate dehydrogenase in liver and epididymal adipose tissue of fed rats. Biochem J. 1976, 160: 413-426.

Oller do Nascimento CM, Williamson DH: Evidence for conservation of dietary lipid in the rat during lactation and the immediate period after removal of the litter. Biochem J. 1986, 239: 233-252.

Arner P, Engfeldt P: Fasting-mediated alteration studies in insulin action on lipolysis and lipogenesis in obese women. Am J Physiol. 1987, 253 (2 Pt 1): E193-E201.

Eggstein M, Kreutz FH: Eine neue bestimmung der neutralfette im blustserum und gewebe: prinzip, durchfuhnrung und besprechung der methode. Klinische Wochenschrift. 1966, 44: 262-267. 10.1007/BF01747716

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) and the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) for the financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

NCC made contributions to the conception and design of the study, generation, collection, assembly, analysis and interpretation of data and drafting the manuscript. ARD made contributions to the conception and design of the study, generation, collection, assembly, analysis and interpretation of data and drafting the manuscript. EAR made contributions to the conception and design of the study, generation, collection, assembly, analysis and interpretation of data and drafting the manuscript. RFLG made contributions to the collection, assembly, analysis of data and revision of the manuscript.

FPV made contributions to the collection, assembly, analysis of data and revision of the manuscript. MSJM made contributions to the collection, assembly, analysis of data and revision of the manuscript. IZC performed the design of the study and interpretation of data. PLS performed the design of the study and interpretation of data. RCV performed the design of the study and interpretation of data. CMON performed the design of the study and interpretation of data.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheik, N.C., Rossi, E.A., Guerra, R.L.F. et al. Effects of a ferment soy product on the adipocyte area reduction and dyslipidemia control in hypercholesterolemic adult male rats. Lipids Health Dis 7, 50 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-511X-7-50

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-511X-7-50