Abstract

Background

Triglyceride concentrations are raised in pregnancy and are considered a key fetal fuel. Several gene variants are known to alter triglyceride concentrations, including those in the Apolipoprotein E (ApoE), Lipoprotein Lipase (LPL), and most recently, the Apolipoprotein AV (ApoAV) gene. However, less is known about how variants in these genes alter triglyceride concentrations in pregnancy or affect fetal growth. We aimed to determine the effect of the recently identified ApoAV gene on triglycerides in pregnancy and fetal growth. We assessed the role of two ApoAV haplotypes, defined by the C and W alleles of the -1131T>C and S19W polymorphisms, in 483 pregnant women and their offspring from the Exeter Family Study of Childhood Health.

Results

The -1131T>C and S19W variants have rare allele frequencies of 6.7% and 4.9% and are present in 13.4% and 9.7% of subjects respectively. In carriers of the -1131C and 19W alleles triglyceride concentrations were raised by 11.0% (1.98 mmol/ l(1.92 – 2.04) to 2.20 mmol/l (2.01 – 2.42), p = 0.035; and 16.2% (1.97 mmol/l (1.91 – 2.03) to 2.29 mmol/l (2.12 – 2.48), p < 0.001 respectively. There is nominally significant evidence that the -1131T>C variant is having an effect on maternal height (164.9 cm (164.3 – 165.5) to 167.0 cm (165.2 – 168.8), p = 0.029). There was no evidence that ApoAV genotype alters any other anthropometric measurements or biochemistries such as High Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (HDL-C) or Low Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (LDL-C). There is nominally significant evidence that the presence of a maternal -1131C variant alters fetal birth length (50.2 cm (50.0 – 50.4) to 50.9 cm (50.3 – 51.4), p = 0.022), and fetal birth crown-rump length (34.0 cm (33.8 – 34.1) to 34.5 cm (34.1 – 35.0), p = 0.023). There is no evidence that ApoAV genotype alters fetal birth weight or other fetal growth measurements.

Conclusion

In conclusion variation in the ApoAV gene raises triglyceride concentrations in pregnancy, as well as normolipaemic states and there is preliminary evidence that it alters fetal growth parameters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Triglycerides are a key fetal fuel in pregnancy. Triglyceride concentrations are raised in pregnancy due to the overproduction of triglyceride rich very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) cholesterol [1]. Pregnancy also elevates total and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterols [2] and lowers high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol [1]. Triglyceride concentrations increase gradually with the duration of pregnancy with significant increases during the second trimester [2]. Triglyceride and cholesterol concentrations return to pre-pregnant concentrations 20–24 weeks post partum [2], with a rapid reduction in triglycerides and cholesterol in breast-feeding mothers compared to mothers where lactation was never established [3].

Triglyceride and cholesterol concentrations are under strong genetic control. Variants in several genes, including, ApoE [1], LPL [1], LDL receptor [4], Apolipoprotein CIII (ApoCIII) [5], Apolipoprotein AIV (ApoAIV) [5] and, recently ApoAV [6] are associated with altered triglyceride and cholesterol concentrations [7]. Despite this, little is known about how these variants alter lipid profiles in pregnancy. In one study of 250 pregnant females from a number of ethnic groups, the genes encoding LPL (S447X and N291S) and ApoE (E2 allele) are associated with altered triglyceride and HDL-cholesterol concentrations in pregnancy [1].

High triglyceride concentrations in pregnancy can result in acute pancreatitis [8] and are associated with pre-eclampsia [9]. In addition to these implications for maternal health, maternal triglyceride concentrations are correlated with offspring birth weight. This correlation is independent of maternal pre-pregnant Body Mass Index (BMI), maternal weight gain, fasting glucose, gender and gestational age [10].

Common variation in the ApoAV gene has recently been shown to have one of the largest effects on triglyceride concentrations in the normal population. ApoAV was recently discovered in the ApoAI/CIII and AIV gene cluster using comparative genomics of human and mouse genomes [6]. Studies on transgenic and knockout mice showed that ApoAV is a key regulator of triglyceride concentrations in mice. In man, two haplotypes of the ApoAV gene, each of ~6.0% frequency in caucasians and defined by the C and W alleles of the -1131T>C and S19W single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP), are associated with increased triglyceride concentrations. Male carriers of one or two copies of the -1131C and 19W have triglyceride concentrations ~40.0% higher than subjects homozygous for the -1131T and 19S alleles [11]. There is less data available in women, but, a study of 442 caucasian women from the Dallas Heart Disease Prevention Project (DHDPP) showed an increase of 22.0% in carriers of either the -1131C or 19W haplotypes [11]. In addition to altering triglyceride concentrations, ApoAV variants have been associated with VLDL-cholesterol (P = <0.001), but not altered HDL-cholesterol or LDL-cholesterol concentrations [11]. Non-pregnant caucasian women were shown to have triglycerides that were 23.0% (17.4% – 36.6%) lower than caucasian males [11], p < 0.05.

The -1131C allele raises triglyceride concentrations in a variety of dyslipidaemic conditions such as hyperlipidaemia, hypoalphalipoproteinaemia and hyperalphalipoproteinaemia from the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Genomic Resource in Arteriosclerosis [7].

The chemical properties of Apolipoprotein AV indicate that it may retard triglyceride-rich particle assembly and may function intracellularly to modulate hepatic Very Low Density Lipoprotein (VLDL) synthesis and/or secretion [12]. The Apolipoprotein AV gene is only expressed in the liver and has a very low plasma concentration. ApoAV may therefore affect plasma triglyceride levels by modulating hepatic VLDL assembly and secretion, rather than the intravascular metabolism of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins [12]. The -1131T>C polymorphism is in the promoter region and may therefore affect transcription of the ApoAV gene. The S19W polymorphism changes the amino acid serine to a tryptophan at codon 19. This change could alter the secondary structure of the protein and alter protein folding, thus altering the function of the protein.

The role of ApoAV gene variants in regulating triglyceride concentrations in pregnancy is not known. To gain a better understanding of the genetic control of triglycerides in pregnancy and potential effects on fetal growth we have examined the role of the variants -1131T>C and S19W in the ApoAV gene in caucasian pregnant women and their offspring. We have shown that two common variants in the ApoAV gene alter triglycerides in pregnancy by 11.0% (1.5% to 22.2%) and 16.2% (7.6% to 25.9%).

Results

Triglyceride concentrations in 483 pregnant females (2.01 mmol/l (1.96 – 2.06)) were higher than those in their male partners (1.34 mmol/l (1.28 – 1.39), p value of <0.001).

Both Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) were in Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium. The frequencies of the two rare alleles were 6.7% for -1131T>C and 4.9% for S19W. Nine point seven percent of subjects are carriers of at least one -1131C allele and 13.4% are carriers of at least one 19W allele with 0.6% carrying both a -1131C and a 19W allele. We did not observe any significant LD between the two variants, D' = 0.33; p >0.5.

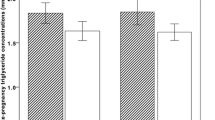

The -1131T>C and S19W ApoAV variants alter triglyceride concentrations in pregnancy

Tables 1 and 2 show the effect on maternal anthropometry and biochemistry for -1131T>C and S19W respectively. Each of the two ApoAV variants was associated with altered triglyceride concentrations in pregnancy. The two SNPs increased triglycerides concentrations by a similar magnitude of effect, the -1131C showed a 11.0% increase (from 1.98 mmol/l (1.92 – 2.04) to 2.20 mmol/l (2.01 – 2.42), p = 0.035), and 19W a 16.2% increase (from 1.97 mmol/l (1.91 – 2.03) to 2.29 mmol/l (2.12 – 2.48), p < 0.001) respectively.

Total Cholesterol concentrations were raised in pregnant females carrying at least 1 rare allele. Subjects with -1131C allele had 6.75 mmol/l (6.40 – 7.11) compared to 6.43 mmol/l (6.31 – 6.53) in non carriers (p = 0.078). Subjects with 19W had 6.73 mmol/l (6.44 – 7.05) compared to 6.37 mmol/l (6.27 – 6.49) in non carriers (p = 0.025). The effect of the -1131T>C variant did not reach significance. There is no evidence of an effect in any of the remaining biochemistry concentrations for either of the polymorphisms.

Subjects carrying at least one rare allele at -1131T>C were 3.7 kg heavier (p = 0.06) and 2.10 cm taller (p = 0.029) than non carriers. There was no evidence for either genotype altering other anthropometric measures.

Triglyceride Concentrations in mothers and fetal growth

Table 3 shows the effect of maternal ApoAV -1131T>C genotype on measures of fetal growth in 483 newborns. There is evidence that maternal genotype alters fetal birth length (from 50.2 cm (50.0 – 50.4) to 50.9 cm (50.3 – 51.4), p = 0.022) and birth crown-rump length (from 34.0 cm (33.8 – 34.1) to 34.5 cm (34.1 – 35.0), p = 0.02). There was no evidence that maternal genotype alters other fetal growth measurements.

Table 4 shows the effect of the maternal S19W genotype on measures of fetal growth. There is no evidence of an effect on any of the fetal growth measurements.

Discussion

We have shown that variation in the ApoAV gene alters triglyceride concentrations in pregnancy. The two haplotypes, defined in this study by the -1131T>C and S19W SNPs, raise triglycerides by 11.0% (1.5% – 22.2%) and 16.2% (7.6% – 25.9%) respectively. The -1131T>C and S19W alleles were previously shown to increase triglyceride concentrations in non-pregnant caucasian females by 22.0% [11]. The -1131T>C variant therefore has a slightly lower magnitude of effect on triglycerides in pregnancy as it does outside pregnancy, although based on our 95% confidence intervals we cannot exclude an effect as small as 1.5% or as large as 22.2% for -1131T>C variant and as small as 7.6% and 25.9% for the S19W variant. Women carrying at least one of either the 19W or -1131C alleles may therefore be at increased risk of complications from raised triglycerides in pregnancy. Further studies are needed to assess this as the size of the increase is modest and the prevalence of clinical complications associated with hypertriglyceridaemia in pregnancy rare.

Evidence so far indicates that the effect of ApoAV variants on altering triglyceride concentrations is not lost or reduced in hyperlipidaemic states. In addition to our results in pregnancy, the -1131C allele was analysed in a variety of dyslipidaemic conditions including hyperlipidaemia, hypoalphalipoproteinaemia and hyperalphalipoproteinaemia from the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Genomic Resource in Arteriosclerosis and increased triglyceride and VLDL-Cholesterol concentrations by 10.7% and 24.2% respectively and marginally reduced HDL-Cholesterol concentration by 4.9% [7]. The -1131C allele was increased in frequency in hyperlipidaemia vs. control (13%) [7]. There was however no evidence of an allelic association with either hypoalphalipoproteinaemia or hyperalphalipoproteinaemia [7].

Both of the variants investigated may have different functional properties. The -1131T>C variant is in the promoter region and is in linkage disequilibrium with a -3A>G variant that is found in the 'kozak' region [13]. This -3A>G variant disrupts a 6 to 8 bp sequence that precedes the initiation methionine and has been previously shown in other genes to severely disrupt ribosomal translation efficiency [13]. The S19W variant is in exon 2 and may cause a variation in the signal sequence which would reduce ApoAV secretion across the endoplasmic reticulum which has been previously seen with the ApoB signal peptide variant [13]. As ApoAV may act as a brake on the transport of triglyceride rich lipoproteins from the liver, these variants would produce lower levels of ApoAV and therefore increase the triglyceride plasma concentrations [13].

Variants in other genes that raise triglycerides are also associated with raised triglycerides in pregnancy. In a study on 250 pregnant Canadian women in their third trimester, the presence of the e4/e4 polymorphism in the ApoE gene increased triglyceride concentrations by 0.4 mmol/l (15%) compared to carriers of the e2/e2 variants. Carriers of the S447X polymorphism in the LPL gene showed a decrease of 0.6 mmol/l (21%) (P = 0.003) compared to non-carriers and carriers of the N291S polymorphism showed an increase of 0.5 mmol/l (19%) (P = 0.2) compared to non-carriers [1].

In addition to effects on triglyceride concentrations in pregnancy we examined the role of maternal ApoAV genotype on fetal growth. Maternal triglyceride concentration correlates strongly with birth weight and therefore genetic effects on triglyceride concentrations in pregnancy could contribute to fetal growth. We found evidence that the presence of a maternal -1131T>C variant produces a 0.67 cm (1.3%) increase in birth length (p = 0.022) and a 0.57 cm (1.7%) increase in fetal birth crown to rump length (p = 0.023). However, further studies will be needed to confirm or refute these observations.

Conclusions

In conclusion we have shown that variants in the ApoAV gene raise 28-week pregnancy triglyceride concentration, in addition to the triglyceride raising effect of pregnancy itself. Preliminary evidence indicates that the gene is having an effect on fetal growth parameters, but, this needs replicating in further studies

Methods

Subjects

Genotyping was performed on 483 pregnant caucasian females and their partners from the Exeter Family Study of Childhood Health. These samples form part of an ongoing study of parent-offspring trios. Women from the central Exeter area were contacted at 25–26 weeks gestation via letter and recruited via telephone one week later. During the 28th week of pregnancy, fasting venous blood samples were taken for biochemical and DNA isolation, as were anthropometric measurements. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects prior to samples and measurements being taken.

A number of fasting blood biochemistries were measured including insulin, glucose, triglycerides, total and HDL-cholesterols, plus LDL-cholesterol (by calculation using the Friedewald formula). All tests were performed in the local Clinical Chemistry laboratory at the Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital using dry slide technology on Vitros 950 analysers (Ortho Clinical) prior to December 2001 and manufacturers' standard reagents on Modular analysers (Roche) thereafter. All local methods demonstrated analytical Coefficients of Variation (CV's) of less than 5%.

Offspring of the mothers had detailed growth measurements at birth, including weight, length, crown/rump length, head circumference, arm circumference, triceps skin fold and sub scapular skin fold. A sample of cord blood was taken at delivery for DNA isolation.

Genotyping

Two ApoAV SNPs were used to define the two haplotypes associated with raised triglyceride concentrations. These were -1131T>C (SNP 3 in [6]) and S19W (c.56C>G in [11]) which changes a Serine to a Tryptophan amino acid at codon 19 [11].

Restriction Length Fragment Polymorphism (RFLP) analysis was used for both SNPs. The -1131T>C and S19W SNPs were genotyped as previously described ([6, 11] respectively) with the following exceptions:

For -1131T>C

The Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) was performed in 10 μl volume reactions containing in addition to the standard reagents: 5 M Betaine, 5% DMSO due to the high GC content of the target product, and 0.4 U of Amplitaq Gold (Applied Biosystems, UK).

PCR cycling conditions were: denaturation at 95°C for 12 mins, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 1 min, annealing at 54°C for 1 min and extension at 72°C for 2 mins, with a final 10 min extension at 72°C.

The PCR was digested using 2 U of MseI (New England Biolabs, UK) and incubated at 37°C overnight. The digested product was run out on a 3% agarose gel for one and a half hours at 200 V.

For S19W

The PCR was performed in a 10 μl volume reaction containing in addition to the standard reagents: 0.4 U of Amplitaq Gold (Applied Biosystems, UK).

PCR cycling conditions were: denaturation at 94°C for 12 mins followed by 34 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 45 secs, annealing at 65°C for 45 secs and extension at 72°C for 45 secs, with a final extension at 72°C for 10 mins.

The PCR product was digested using 7 U of EagI and incubated at 37°C overnight. The digested product was run out on a 3% agarose gel for one and a half hours at 200 V.

We performed extensive genotype quality control checks, including confirming the presence of any rare homozygotes by re-genotyping and sequencing, scoring gels on two separate occasions and re-genotyping 10% of randomly chosen samples. Overall genotyping results were obtained in 94.5% of the samples and no errors in genotyping were detected.

Statistics

Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium for each SNP was tested by comparing observed genotype numbers with expected genotype numbers based on observed allele frequencies, using a Chi-square analysis.

The LDMAX function of GOLD software was used to calculate the Linkage Disequilibrium (LD) between the two SNPs.

The correlation between maternal triglycerides, HDL-cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol and measures of fetal growth were calculated using regression analysis with SPSS.

The associations between the genotype of each SNP and triglyceride concentrations were performed using univariate general linear model analysis in SPSS. Each genotype was looked at independently and samples that contained at least one copy of the rare allele for the other SNP were not included in the analysis. All non-normally distributed data was log-transformed and back transformed geometric means and 95% Confidence Intervals are quoted.

Maternal anthropometry was uncorrected and maternal biochemistry measures were corrected for weight (with the exception of glucose that was corrected for age and weight due to their significant effect on glucose).

Gestational age was corrected for sex and all other fetal growth measurements were corrected for gestational age and sex.

The comparison between pregnant female and male triglyceride concentrations were determined using an Independent T-Test.

References

McGladdery SH, Frohlich JJ: Lipoprotein lipase and apoE polymorphisms: relationship to hypertriglyceridemia during pregnancy. J Lipid Res. 2001, 42 (11): 1905-12.

Choi JW, Pai SH: Serum lipid concentrations change with serum alkaline phosphatase activity during pregnancy. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2000, 30 (4): 422-8.

Qureshi IA, Xi XR, Limbu YR, Bin HY, Chen MI: Hyperlipidaemia during normal pregnancy, parturition and lactation. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1999, 28 (2): 217-21.

Brorholt-Petersen JU, Jensen HK, Jensen JM, Refsgaard J, Christiansen T, Hanse Gregersen N, Faergeman O: LDL receptor mutation genotype and vascular disease phenotype in heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia. Clin Genet. 2002, 61 (6): 408-15. 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2002.610603.x

Talmud PJ, Hawe E, Martin S, Olivier M, Miller GJ, Rubin EM, Pennacchio LA, Humphries SE: Relative contribution of variation within the ApoC3/A4/A5 gene cluster in determining plasma triglycerides. Human Mol Genet. 2002, 11 (24): 3039-3046. 10.1093/hmg/11.24.3039. 10.1093/hmg/11.24.3039

Pennacchio LA, Olivier M, Hubacek JA, Cohen JC, Cox DR, Fruchart JC, Krauss RM, Rubin EM: An apolipoprotein influencing triglycerides in humans and mice revealed by comparative sequencing. Science. 2001, 294 (5540): 169-73. 10.1126/science.1064852

Aouizerat BE, Kulkarni M, Heilbron D, Drown D, Raskin S, Pullinger CR, Malloy MJ, Kane JP: Genetic analysis of a polymorphism in the human apoA-V gene: effect on plasma lipids. J Lipid Res. 2003, 44 (6): 1167-73. 10.1194/jlr.M200480-JLR200

Schaefer EJ, McNamara JR, Genest J, Ordovas JM: Clinical significance of hypertriglyceridemia. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1988, 14 (2): 143-8.

Hubel CA, McLaughlin MK, Evans RW, Hauth BA, Sims CJ, Roberts JM: Fasting serum triglycerides, free fatty acids, and malondialdehyde are increased in pre-eclampsia, are positively correlated, and decrease within 48 hours post partum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996, 174 (3): 975-82.

Sherman RC, Burdge GC, Ali Z, Singh KL, Wootton SA, Jackson AA: Effect of pregnancy of plasma lipid concentration in Trinidadian women. Result of a pilot study. West Indian Med J. 2001, 50 (4): 282-7.

Pennacchio LA, Olivier M, Hubacek JA, Krauss RM, Rubin EM, Cohen JC: Two independent apolipoprotein A5 haplotypes influence human plasma triglyceride levels. Hum Mol Genet. 2002, 11 (24): 3031-8. 10.1093/hmg/11.24.3031

Weinberg RB, Cook VR, Beckstead JA, Martin DDO, Gallagher JW, Shelness GS, Ryan RO: Structure and interfacial properties of Human Apolipoprotein A-V. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003, 278 (36): 34438-44. 10.1074/jbc.M303784200

Martin S, Nicaud V, Humphries SE, Talmud PJ, EARS Group: Contribution of ApoA5 gene variants to plasma triglyceride determination and to the response to both fat and glucose challenges. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2003, 1637 (3): 217-25. 10.1016/S0925-4439(03)00033-4

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Len A. Pennacchio, Berkley University, California for the helpful discussion regarding the ApoAV gene.

This work was principally funded by Diabetes Research and Education Trust (DIRECT) and The University of Exeter, UK, through a studentship for KJW. The funding for the collection of the samples analysed for the Exeter Family Study of Childhood Health was provided by South and West National Health Service Directorate, Exeter, UK. BS is a Research Assistant with the Medical Research Council, Exeter, UK. BK has a research studentship with the South and West National Health Service Directorate, Exeter, UK. MBS is an NHS Consultant in Clinical Chemistry with the Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital, Exeter, UK. ATH is a Wellcome Trust Career Leave Research Fellow, Exeter, UK. TMF is a career scientist for the South and West National Health Service Directorate, Exeter, UK.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

KJW carried out the molecular genetic studies, performed statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. BS collated and organised all phenotypic data. BK was responsible for sample collection and measurements of anthropometric phenotypes. MBS was responsible for all biochemical analysis. ATH and TMF conceived and designed the molecular genetics study and participated in it's design and coordination. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Ward, K.J., Shields, B., Knight, B. et al. Genetic variants in Apolipoprotein AV alter triglyceride concentrations in pregnancy. Lipids Health Dis 2, 9 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-511X-2-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-511X-2-9