Abstract

Malaria and anaemia are important health problems among children globally. Iron deficiency anaemia may offer protection against malaria infection and iron supplementation may increase the risk of malaria-related hospitalization and mortality. The nature and mechanism of these relationships, however, remain largely unresolved, resulting in concern and uncertainty around policies for non-selective iron supplementation in malaria endemic areas. Use of geographical information systems (GIS) to investigate this disease-disease interaction could contribute important new information for developing safe and effective anaemia and malaria interventions. To assess the current state of knowledge we conducted a systematic review of peer-reviewed and grey literature. Our primary objective was to qualitatively assess the application and utility of geographical concepts or spatial analyses in paediatric global health research. The secondary objective was to identify geographical factors that may be associated with anaemia and malaria prevalence or incidence among children 0–5 years of age living in low- and middle-income countries. Evaluation tools for assessing the quality of geographical data could not be found in the peer-reviewed or grey literature, and thus adapted versions of the STROBE (Strengthening The Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) and GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) methods were used to create reporting, and overall evidence quality scoring systems. Among the 20 included studies, we found that both malaria and anaemia were more prevalent in rural communities compared to urban areas. Geographical factors associated with malaria prevalence included regional transmission stability, and proximity to a mosquito breeding area. The prevalence of anaemia tended to vary inversely with greater or poorer access to community services such as piped water. Techniques for investigating geographic relationships ranged from simple descriptive mapping of spatial distribution patterns, to more complex statistical models that incorporated environmental factors such as seasonal temperature and rain fall. Including GIS in paediatric global health research may be an effective approach to explore relationships between childhood diseases and contribute key evidence for safe implementation of anaemia control programs in malaria endemic areas. Further, GIS presentation of ecological health data could provide an efficient means of translating this knowledge to lay audiences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Review

Background

Pediatric public health problems in a global context

Childhood malnutrition and infection make up a large proportion of the global health disease burden [1]. Anaemia and malaria, in particular, are among the most important public health issues worldwide, especially in low and middle-income countries [2, 3]. There are several potential causes of anaemia, with iron deficiency as the largest contributor in approximately half of all cases [2]. Generally, anaemia is a marker of both poor health and poor nutrition, and severe anaemia has been shown to increase the risk of child mortality [4, 5]. Other important causal factors of anaemia include parasitic infections, such as malaria [6]. Most malaria infections are caused by Plasmodium falciparum, and is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality among children in sub-Saharan Africa [7, 8]. Malaria causes anaemia primarily through haemolysis, the destruction of red blood cells [9]. Along with other haeme-related disorders, such as inherited thalassaemia and haemoglobinopathies, it has also been suggested that iron deficiency may offer protection against malaria infection [10]. On the contrary, evidence from a large randomized controlled trial in Pemba, Zanzibar (> 30,000 participants) suggested that providing iron supplements to young children living in a malaria endemic area who are iron replete may increase the risk of malaria-related hospitalization and mortality [11]. This trial was the first of its kind to be adequately powdered to investigate mortality as a primary outcome; and the findings have fuelled much debate within the scientific community over the nature of the interaction between malaria and anaemia, and the potential biological mechanisms that drive this relationship. As a result, concern and uncertainty were generated within the global health community, especially around policies for routine and non-selective iron supplementation in areas where malaria is highly prevalent.

Geographic information systems in health research

A geographical information system (GIS) constitutes a system of hardware and software used for storage, management, retrieval, manipulation, analysis, modeling, and mapping of geographical data [12]. It is an “enabling technology” that is relatively easy to use and access by non-experts in geography or cartography with basic computer literacy and map reading skills. There are several potential advantages of using GIS to investigate global health issues [13]: 1) it allows the exploration of the role of geographical or environmental factors in the prevalence (or incidence) of a health outcome of interest; 2) the combination of cartography and multivariate analysis allows investigation of complex spatial relationships (e.g. linking people and health outcomes to space and time); 3) GIS software enables the presentation of research findings in a visual manner that can be easily interpreted across disciplines; and 4) the technique can be applied to a range of analysis units, which may provide insight into relationships between health outcomes and other social, demographic, or economic variables at various jurisdictional levels. Although the use of GIS technology is expanding on a global scale (as indicated by ESRI licensing records alone), potential limitations of its use may include the lack of available geographically referenced data and the prohibitive cost of collecting such information, especially in remote or low-resource settings. More recently, however, the development of open-access GIS platforms, as well as initiatives by the United Nations (UN) and other government organizations (e.g. IDRC, WHO and CDC) have increased the accessibility and availability GIS software for low- and middle-income countries [14].

Geospatial analysis can facilitate identification of the most vulnerable populations in terms of a disease outcome of interest, and thus contribute valuable information for planning targeted public health interventions. Assessments of the relationships between anaemia and malaria have not generally included geographical factors. Considering that the burden of anaemia and malaria is highest among children from poorer parts of low- and middle-income countries, these two prominent health problems could share common ecological and geographical settings. A systematic exploration and appraisal of current evidence regarding the application of GIS and spatial analysis in the investigation of these problems could be beneficial.

Objectives of the systematic review

Our primary objective was to determine how geographical concepts or spatial analyses have been applied to the investigation of anaemia and malaria outcomes among young children in low-resource settings; as well as discuss the potential utility of these applications. The secondary objective was to identify geographical factors that may be associated with anaemia and malaria prevalence or incidence among children 0–5 years of age living in low- and middle-income countries

Methods

Peer-reviewed literature search

Relevant peer-reviewed journal databases (PUBMED, MEDLINE, EMBASE, SCOPUS, WEB OF SCIENCE) were searched using the following terms and operators: (spatial OR “space-time” OR geostat* OR gis OR “geographic* information system*”) AND (child* OR infant* OR newborn OR neonat*) AND (“low income” OR “middle income” OR “developing country” OR “low resource”) AND (anemia OR anaemia OR “iron deficiency” OR hemoglobin OR haemoglobin OR malaria). The titles and abstracts of all records were screened by two reviewers using the following relevance criteria:

-

Population: study population includes children ≤ 5 years of age living in low or middle income countries (World Bank classification)

-

Approach: use of geographical or ecological-level data with/without spatial analysis

-

Co-approach: complimentary or comparative use of individual-level data (or other “non-geographical” factors) and corresponding analysis methods

-

Outcomes: anaemia, malaria

-

Exclusions: animal studies, in-vitro studies

Grey literature search and hand searches

Grey literature sources were sought by hand searching the reference lists of selected studies; searching publication lists of major international organizations involved in global pediatric health research and promotion (e.g. WHO and UNICEF); and conducting online searches for companies, institutions, or research groups involved in GIS work with a public health focus (e.g. Infonaut, Sault Ste. Marie Innovation Centre, MEASURE DHS, MARA, and MAP).

Data Screening and extraction

The full text versions of records from peer-reviewed and grey literature sources that met relevance criteria, based on the title and abstract, were retrieved and the data extracted onto pre-designed forms. For those records with titles and abstracts that did not contain enough information to assess relevance, the full texts were retrieved and screened. In order to assess inter-reviewer reliability, a subset of 30 records was randomly selected and the titles/abstracts independently screened by the two reviewers using the relevance criteria described above. The results of these independent screenings were compared through the calculation of a Kappa statistic, which quantifies the measure of agreement between independent reviewer assessments, taking into account the probability of chance agreements [15]. When there was disagreement in terms of relevance, the two reviewers met and reached consensus. If consensus could not be reached, a third independent reviewer was consulted to resolve the discrepancy.

Quality assessment

Literature quality was not included as a relevance criterion, and thus quality assessments were conducted after the full text screening and selection processes. As it was anticipated that the majority of the health outcome data reviewed would be observational in nature, the quality of reporting these outcomes were evaluated using the STROBE method (Strengthening The Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) [16, 17]. An example of a similar evaluation tool for assessing the quality of reporting geographical data could not be found in the peer-reviewed or grey literature; however, the ‘Metadata Standards’ of the US National Centre for Geographic Information and Analysis (NCGIA) guidelines were adopted as evaluation criteria. Under the ‘Metadata’ model, transparency in documentation is a requirement for meeting this standard, and thus studies that included a description of how the spatial data were produced were given a higher quality rating than those that did not. These criteria were included in an adapted version of the STROBE checklist (Table 1), which was used to create a binomial scoring system (e.g. 1 = criterion met, 0 = criterion not met). Final score percentages were based on the number of reporting quality criteria met divided by the number of criteria that were relevant (e.g. criterion for case control studies will not apply to evaluation reports).

The overall quality of evidence from selected studies was assessed using the GRADE approach (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation Working Group 2004). Under this approach, assessing the quality of a body of evidence involves consideration of within-study risk of bias, and data quality. The approach specifies four levels of quality: high (+2), moderate (+1), low (0), and very low (≤ −1). Quality ratings may be downgraded or upgraded based on the presence of eight factors [18]: 1) Limitations in design and implementation; 2) Indirectness of evidence; 3) Unexplained heterogeneity or inconsistency of results; 4) Imprecision of results; 5) High probability of publication bias; 6) Large magnitude of effect; 7) All plausible confounding would reduce a demonstrated effect or suggest a spurious effect when results show no effect; 8) Dose–response gradient.

The GRADE approach was originally developed to assess the quality of medical evidence from clinical studies, and there did not appear to be a similar validated evaluation tool for assessing the quality of geographic evidence. There is, however, a sufficiently large body of literature on spatial data quality that could be used to create an adapted version of the GRADE approach. As such, relevant data quality elements extracted and compiled from various sources[19, 20], including: 1) Accuracy (a component of quality that can be defined in terms of the entity-attribute-value model); 2) Resolution (the amount of detail that can be discerned in space, time or theme); 3) Consistency (the absence of apparent contradictions in a database); 4) Completeness (lack of errors of omission in a database relative to the database specification).

Verifying the accuracy and completeness of spatial data, while especially important to consider in quantitative analyses and interpretations, was not deemed necessary for addressing the objectives of this qualitative review. However, the resolution (precision) and consistency of geographical maps and mapping techniques used by authors to display and interpret health outcome data was assessed using an adapted GRADE approach. In the case of precision, studies that presented spatial data with insufficient detail to allow appropriate discernment of spatial, temporal, or thematic resolution were given lower quality ratings. In terms of consistency, if there were apparent contradictions in the spatial, temporal, or thematic evidence that were not adequately explained by the investigators, quality ratings were decreased.

Data synthesis

Due to the observational and heterogeneous nature of the literature retrieved, a qualitative synthesis (rather than a meta-analytic assessment) of the data was performed. Patterns in the data within and between studies were analysed inductively. Methods used to apply geographical concepts or spatial analyses were similarly assessed.

Results

Literature search, data synthesis and quality assessment

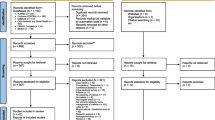

A total of 102 records were retrieved from peer-reviewed and grey literature sources, as well as through individual hand searches. Of these records, 13 were duplicates and 69 did not meet relevance criteria (Figure 1). The primary reasons for rejection were: 1) lack of data pertaining to a target population in the specified age range of 0–5 years (25 records); and 2) lack of data on anaemia or malaria outcomes (25 records). The Kappa score for the sub-sample of independently reviewed titles/abstracts was 0.61, reflecting a good agreement between the two reviewer assessments [15]. Twenty records remained for inclusion in this review and underwent quality assessments and data synthesis.

A description of all selected studies, ranked according to their reporting quality ratings, is presented in Table 2. Six out of twenty records included anaemia as a primary outcome [2, 21–24], while the rest were focused on malaria. The target population in 75% (15/20) of the selected studies and reports were from single or multiple countries in Africa. Three reports, all published by the WHO, pertained to all children globally, and 1 record included a target population from Asia (Indonesia). Reporting quality scores ranged from 41.4% to 88.3%, with the majority of records (13/20) having final scores between 60 and 80%. In terms of the quality of evidence, 4 studies were upgraded once, mainly due to reporting dose–response gradient-like relationships between a geographic factor and the prevalence/incidence of malaria or anaemia outcomes [24–27]. Three studies were upgraded twice due to dose–response relationships and additional control or consideration of confounders and potential biases [21, 28, 29]. All downgraded records (8/20) were given ratings of −1 due to the indirectness of results (e.g. spatial analysis was applied to whole population data rather those specific to young children; or geographic relationships were inferred from inter-site or cross-country comparisons).

GIS applications and spatial analyses of malaria and anaemia among children

Table 3 summarizes the results from selected records in terms of GIS applications and the observed geographic factors associated with malaria or anaemia among young children. The use of GIS and spatial analysis ranged from simple descriptive maps of study areas [22, 25, 36], to more complex depictions of environmental or spatial predictors of health outcomes. The most common GIS application was describing the distribution and spatial patterns of anaemia and malaria-related outcomes (e.g. disease prevalence or incidence, vector transmission or parasitology) using thematic mapping, such as choropleth or dot density [2, 7, 24, 27, 29, 31, 33, 34, 37–39]. The Mapping Malaria Risk in Africa (MARA) project, and more recent initiative, Malaria Atlas Project (MAP), have reported extensive use of GIS combined with fuzzy logic (MARA) and posterior predictive modeling (MAP), to estimate malaria risk according to levels of parasite endemicity, transmission stability, and climate suitability [26, 30, 32, 35, 40]. GIS has also been combined with other types of geostatistical methods – such as Bayesian geostatistical models [24, 28], and geographically weighted regression [21] – to estimate the spatial distribution of burden and environmental predictors of malaria and anaemia (e.g. climate or urbanization).

According to the WHO reports included in this review (Table 3), annual childhood mortality from malaria in 2002 were highest in Africa (978, 661 deaths/year) , followed by South-East Asia (57, 877 deaths/year) [38], and this global pattern has been consistently supported by malaria incidence data from 160 endemic countries up to 2009 [7, 33], as well as global malaria risk tables and prevalence distribution maps produced by the Malaria Atlas Project [40]. Variations in malaria prevalence within countries have also been reported in both Asia and Africa. Anthony et al. found lower prevalence in areas of Indonesia among populations living outdoors on forest-covered mountain slopes compared to villagers living in houses [37]. In Senegal, Giardina’s group reported higher malaria prevalence in rural areas compared to urban areas [28], while in Kenya, a higher prevalence of parasitaemia was found among young children from households that were closer to mosquito larval habitats, particularly during months with heavier rainfall [27]. Similarly, Schellenberg et al. reported higher malaria-related hospital admission rates among children who lived closer to a hospital (< 5 km vs. > 25 km) and the nearest road (< 0.5 km vs. > 2.5 km) [26]. Spatial variations in malaria mortality and morbidity rates, clinical malaria incidence, and severe malaria infections have been found to be associated with geographical variations in transmission stability, level of endemicity, and/or entomological inoculation rate [30–32, 34, 36, 41], which are also influenced by local climate and climatic trends [30].

In terms of anaemia, worldwide prevalence among pre-school aged children was estimated by the WHO using country-specific data spanning from 1993–2005 [2]. Similar to the global distribution of malaria, anaemia prevalence appears to be highest in Africa (67.6%, 95% C.I. 64.3-71.0), followed closely by South-East Asia (65.5%, 95% C.I. 61.0-70.0) [2]. At the country level, inverse associations were found between the prevalence of moderate anaemia and the level of urbanization in two studies [21, 42]. Using geographically weighted regression (GWR), Mainardi et al. also reported a significant association between access to a water source (defined by the median number of minutes to attain) and the prevalence of moderate anaemia (defined as haemoglobin 7–9.9 g/dl) among children < 5 years of age (p < 0.01), but not severe anaemia [21]. Two studies reported prevalence data for both malaria and anaemia [22, 29]. Snow et al. compared the health outcomes of young children (0–4 years of age) from two East African communities with markedly different levels of malaria transmission– Kilifi, Kenya and Ifakara, Tanzania – and found that the site with a higher prevalence of severe anaemia also had higher parasitaemia [22]. Conversely, Greenwell et al. found the highest risk of severe anaemia among children in areas of moderate malaria prevalence [29].

Discussion

GIS applications and spatial analyses of malaria and anaemia among children

The literature reviewed herein has demonstrated that geo-spatial concepts and analysis techniques are generally used to describe geographical variation in an outcome measure, sometimes in concurrence with variations in other spatial and non-spatial factors such as time, or climate. Descriptive statistics were presented mainly through thematic maps (e.g. choropleth or dot density). Overall, the evidence has also indicated that geographic factors play a role in the prevalence of malaria and anaemia among young children living in low- and middle-income countries

Spatial analyses and statistical modeling have revealed both positive and negative associations between various geographic factors and the prevalence of malaria, or other related outcomes (such as malaria-related mortality). In some cases, the geographical factors that were associated with malaria prevalence (e.g. distance to larval habitat and transmission stability) were also modified by climatic trends such as seasonal rainfall and regional temperature gradients. Although GIS was not applied as extensively in the anaemia literature retrieved, there were notable similarities in the findings, namely the inverse association between anaemia prevalence and level of urbanization, as well as access to a community service such as piped water. In other words, anaemia has been found to be more common among rural and isolated communities with poorer access to a reliable source of water. The fact that anaemia and malaria share common biological pathways – through red blood cell turnover – and have similar continental-level spatial patterns (e.g. highest prevalence in both Africa and South-East Asia) suggests a geo-biological link that should be investigated further.

Strengths and limitations

Approximately half of the peer-reviewed papers retrieved were published prior to the year 2000, and all studies were observational. The former may be a reflection of the search strategy used; however, we remain confident that the sources included, from both the peer-reviewed and grey literature, have provided a fair depiction of GIS applications in paediatric global health research pertaining to malaria and anaemia. In the latter case, the Cochrane Collaboration has tended to regard observational research as lower quality in terms of evidence for informing intervention effectiveness [43]. Considering that the investigation of geographical patterns and spatial relationships related to health outcomes lends itself almost exclusively to non-experimental study designs, using the Cochrane criteria for evaluating evidence may bias the results for a study towards ‘low’ quality when in fact it is closer ‘moderate’ or ‘high’ relative to other studies in the field, and after accounting for other factors that are more relevant to this topic area (rather than intervention research). GRADE and STROBE are published and verified approaches for evaluating research quality that were adapted in order to account for the potential bias mentioned above, as well as the variability in quality across studies, while maintaining transparency regarding the characteristics of the body of literature reviewed [16, 17, 43]. These novel assessment tools while innovative and potentially ground-breaking, in terms of their contribution to GIS literature reviews, should be further tested and formally evaluated for validity and reliability. Lastly, unlike the Cochrane method [43], quality ratings were not included as part of the relevance criteria. Without prior knowledge of the current range or nature of global paediatric health research that includes GIS, this methodological modification was considered important for determining the extent of research activity, as well as identifying potential opportunities to inform future research agendas in this area.

Conclusions

Overall, we found that the investigation of geographic relationships with specific health outcomes has extended beyond simply mapping and describing spatial distribution patterns, to more complex analyses and predictive modelling to incorporate the effect of other environmental and spatial factors, such as regional variations in climate and distributions in population density. Bearing in mind the potential barriers of GIS use (e.g. lack of available data or prohibitive cost), it was somewhat discouraging that the application of GIS in paediatric anaemia and malaria research was so limited. Especially in the case of anaemia, as the burden of this disease among children under five years is equally if not even more widespread than malaria; and a plethora of prevalence and evaluation data exist that would be amenable to geographical mapping and spatial analysis. Current interest in the interaction between malaria and iron deficiency anaemia, may present an ideal opportunity to employ GIS to explore this relationship further. Such research could benefit local health officials and policy makers in malaria endemic areas who are still without definitive guidelines for planning and implementing anaemia control programs.

Abbreviations

- DHS:

-

Demographic and health survey

- ESRI:

-

Environmental systems research institute

- GIS:

-

Geographical information systems

- GRADE:

-

Grades of recommendation, assessment, development and evaluation

- GWR:

-

Geographically weighted regression

- MARA:

-

Mapping malaria risk in Africa

- MAP:

-

Malaria atlas project

- NCGIA:

-

National centre for geographic information and analysis

- STROBE:

-

Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology

- UNICEF:

-

United nations children’s fund

- WHO:

-

World health organization.

References

Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, Caulfield LE, de Onis M, Ezzati M, Mathers C, Rivera J, Group MaCUS: Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet. 2008, 371 (9608): 243-260. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61690-0.

WHO: WHO Global Database on Anaemia. Worldwide prevalence of anaemia 1993–2005. 2008, Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization

Black RE, Morris SS, Bryce J: Where and why are 10 million children dying every year?. Lancet. 2003, 361 (9376): 2226-2234. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13779-8.

Macgregor M: Maternal anaemia as a factor in prematurity and perinatal mortality. Scott Med J. 1963, 8: 134-

Scholl TO, Hediger ML: Anemia and iron-deficiency anemia: compilation of data on pregnancy outcome. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994, 59 (2 Suppl): 492S-500S. discussion 500S-501S

WHO/UNICEF/UNU: Iron deficiency anaemia: assessment, prevention and control: a guide for programme managers. 2001, Geneva: World Health Organization

WHO: World Malaria Report 2008. 2008, Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization

Breman JG: The ears of the hippopotamus: manifestations, determinants, and estimates of the malaria burden. AmJTrop Med Hyg. 2001, 64 (1–2 Suppl): 1-11.

Ojukwu JU, Okebe JU, Yahav D, Paul M: Oral iron supplementation for preventing or treating anaemia among children in malaria-endemic areas. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009, 8 (3): CD006589-

Nyakeriga AM, Troye-Blomberg M, Dorfman JR, Alexander ND, Bäck R, Kortok M, Chemtai AK, Marsh K, Williams TN: Iron deficiency and malaria among children living on the coast of Kenya. J Infect Dis. 2004, 190 (3): 439-447. 10.1086/422331.

Sazawal Z, Black RE, Ramsan M, Chwaya HM, Stoltzfus RJ, Dutta A, et al: Effects of routine prophylactic supplementation with iron and folic acid on admission to hospital and mortality in preschool children in a high malaria transmission setting: community-based, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2006, 367: 133-143. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)67962-2.

Delaney J: Geographical Information Systems: An Introduction. 1999, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Nykiforuk C, Flaman L: Technical report #08-001. Exploring the utilization of geographic information systems in health promotion and public health. 2008, Edmonton, AB, Canada: School of Public Health, University of Alberta

Mapping Software and Data. http://www.esri.com,

Higgins JPT, Deeks JJ: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 510 (updated March 2011). Edited by: Higgins JPT, Deeks JJ. 2011, Chapter 7: Selecting studies and collecting data, The Cochrane Collaboration,

Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Mulrow CD, Pocock SJ, Poole C, Schlesselman JJ, Egger M, Initiative S: Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Epidemiology. 2007, 18 (6): 805-835. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181577511.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, Initiative S: The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Epidemiology. 2007, 18 (6): 800-804. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181577654.

Schunemann HJ, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Higgins JPT, Deeks JJ, Glasziou P, Guyatt H: Chapter 12: Interpreting results and drawing conclusions. Cochrane Handbook for systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. Edited by: Higgins JPT, Green S. 2011, London, UK: The Cochrane Collaboration

Kumi-Boateng B, Yakubu I: Assessing the quality of spatial data. Eur J Sci Res. 2010, 43 (4): 507-515.

Veregin H: NCGIA Core Curriculum in Geographic Information Science. Data Quality Measurement and Assessment. 1998, Santa Barbara, CA, USA: National Centre for Geographic Information and Analysis at the University of California Santa Barbara

Mainardi S: Modelling spatial heterogeneity and anisotropy: child anaemia, sanitation and basic infrastructure in sub-Saharan Afrca. Int J Geogr Inf Sci. 2012, 26 (3): 387-411. 10.1080/13658816.2011.585612.

Snow RW, de Bastos Azevedo I, Lowe BS, Kabiru EW, Nevill CG, Mwankusye S, Kassiga G, Marsh K, Teuscher T: Severe childhood malaria in two areas of markedly different falciparum transmission in east Africa. Acta Trop. 1994, 57 (4): 289-300. 10.1016/0001-706X(94)90074-4.

WHO: Situational analysis of iron deficiency anaemia in South-East Asian countries: a regional overview. 1995, Salaya, Thailand: World Health Organization

Magalhães RJ, Clements AC: Mapping the risk of anaemia in preschool-age children: the contribution of malnutrition, malaria, and helminth infections in West Africa. PLoS Med. 2011, 8 (6): e1000438-10.1371/journal.pmed.1000438.

Mbogo CN, Snow RW, Kabiru EW, Ouma JH, Githure JI, Marsh K, Beier JC: Low-level plasmodium falciparum transmission and the incidence of severe malaria infections on the kenyan coast. AmJTrop Med Hyg. 1993, 49 (2): 245-253.

Schellenberg JA, Newell JN, Snow RW, Mung’ala V, Marsh K, Smith PG, Hayes RJ: An analysis of the geographical distribution of severe malaria in children in kilifi district, kenya. Int J Epidemiol. 1998, 27 (2): 323-329. 10.1093/ije/27.2.323.

Hightower AW, Ombok M, Otieno R, Odhiambo R, Oloo AJ, Lal AA, Nahlen BL, Hawley WA: A geographic information system applied to a malaria field study in western Kenya. AmJTrop Med Hyg. 1998, 58 (3): 266-272.

Giardina F, Gosoniu L, Konate L, Diouf MB, Perry R, Gaye O, Faye O, Vounatsou P: Estimating the burden of malaria in senegal: bayesian zero-inflated binomial geostatistical modeling of the MIS 2008 data. PLoS One. 2012, 7 (3): e32625-10.1371/journal.pone.0032625.

Greenwell F, Neuman M: Children’s Anemia levels in west africa: a good proxy for malaria morbidity?. 2006, America: Population Association

Snow RW, Craig M, Deichmann U, Marsh K: Estimating mortality, morbidity and disability due to malaria among Africa’s non-pregnant population. Bull World Health Organ. 1999, 77 (8): 624-640.

MARA/ARMA: Towards and Atlas of Malaria Risk in Africa: First Technical Report of the MARA/ARMA Collaboration. 1998, Durban, South Africa: MARA/ARMA Investigating Centre

Snow RW, Gouws E, Omumbo J, Rapuoda B, Craig MH, Tanser FC, le Sueur D, Ouma J: Models to predict the intensity of plasmodium falciparum transmission: applications to the burden of disease in kenya. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1998, 92 (6): 601-606. 10.1016/S0035-9203(98)90781-7.

WHO: World Malaria Report 2010. 2010, Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization

Root GP: Disease environments and subnational patterns of under-five mortality in sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Popul Geogr. 1999, 5 (2): 117-132. 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1220(199903/04)5:2<117::AID-IJPG127>3.0.CO;2-I.

Snow RW, Craig MH, Deichmann U, le Sueur D: A preliminary continental risk map for malaria mortality among African children. Parasitol Today. 1999, 15 (3): 99-104. 10.1016/S0169-4758(99)01395-2.

Mbogo CN, Snow RW, Khamala CP, Kabiru EW, Ouma JH, Githure JI, Marsh K, Beier JC: Relationships between plasmodium falciparum transmission by vector populations and the incidence of severe disease at nine sites on the kenyan coast. AmJTrop Med Hyg. 1995, 52 (3): 201-206.

Anthony RL, Bangs MJ, Hamzah N, Basri H, Purnomo , Subianto B: Heightened transmission of stable malaria in an isolated population in the highlands of irian jaya, indonesia. AmJTrop Med Hyg. 1992, 47 (3): 346-356.

Gordon B, Mackay R, Rehfuess E: Inheriting the world: the atlas of Children’s health and the environment. 2004, Brighton, UK: Myriad Editions Limited

TNBS/ICFI: 2010 Tanzania Atlas of Maternal Health, Child Health, and Nutrition. 2012, Calverton, Maryland, USA: Tanzania National Bureau of Statistics and ICF International

Malaria Atlas Project. http://www.map.ox.ac.uk,

Snow RW, Nahlen B, Palmer A, Donnelly CA, Gupta S, Marsh K: Risk of severe malaria among African infants: direct evidence of clinical protection during early infancy. J Infect Dis. 1998, 177 (3): 819-822. 10.1086/517818.

Brink EW, Aly HE, Dakroury AM, Said AK, Ghoneme FM, Hussein MA, Shaheen FM, Peck RE, Gentry ED, Nichaman MZ: The egyptian national nutrition survey, 1978. Bull World Health Organ. 1983, 61 (5): 853-860.

Higgins JPT, Green S: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. 2011, London, UK: The Cochrane Collaboration

Acknowledgements

We thank Stanley Zlotkin for making substantial contributions to project conception, and critically reviewing the manuscript. Funding for this review was provided by the Hospital for Sick Children Research Training Centre (AA). This funding body did not play a role in any aspect of producing this review, from research design to manuscript preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

Outside of the interests associated with their affiliations and the acknowledgements, the authors do not have financial or non-financial competing interests to disclose.

Authors’ contributions

AMA conceived the project and developed the overall research plan and oversaw the study, conducted the research, synthesized and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. NP conducted the research, and reviewed the manuscript. DCC was involved in project conception and study oversight, and contributed to various phases of the project from reviewing the protocol, conducting the research, and reviewing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Aimone, A.M., Perumal, N. & Cole, D.C. A systematic review of the application and utility of geographical information systems for exploring disease-disease relationships in paediatric global health research: the case of anaemia and malaria. Int J Health Geogr 12, 1 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-072X-12-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-072X-12-1