Abstract

Background

Tobacco use is a leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality. In the developed nations where the burden from infectious diseases is lower, the burden of disease from tobacco use is especially magnified. Understanding the factors that may be associated with adolescent cigarette smoking may aid in the design of prevention programs.

Methods

A secondary analysis of the 2004 United States National Youth Tobacco Survey was carried out to estimate the association between current cigarette smoking and selected smoking-related variables. Study participants were recruited from middle and high schools in the United States. Logistic regression analysis using SUDAAN software was conducted to estimate the association between smoking and the following explanatory variables: age, sex, race-ethnicity, peer smoking, living in the same household as a smoker, amount of pocket money at the disposal of the adolescents, and perception that smoking is not harmful to health.

Results

Of the 27727 respondents whose data were analysed, 15.9% males and 15.3% females reported being current cigarette smokers. In multivariate analysis, compared to Whites, respondents from almost all ethnic groups were less likely to report current cigarette smoking: Blacks (OR = 0.52; 95% CI [0.44, 0.60]), Asians (OR = 0.45; 95% CI [0.35, 0.58]), Hispanic (OR = 0.81; 95% CI [0.71, 0.92]), and Hawaii/Pacific Islanders (OR = 0.69; 95% CI [0.52, 0.93]). American Indians were equally likely to be current smokers as whites, OR = 0.98 [95% CI; 0.79, 1.22]. Participants who reported living with a smoker were more than twice as likely to smoke as those who did not live with a cigarette smoker (OR = 2.73; 95% CI [2.21, 3.04]). Having friends who smoked was positively associated with smoking (OR = 2.27; 95% CI [1.91, 2.71] for one friend who smoked, and OR = 2.71; 95% CI [2.21, 3.33] for two or more friends who smoked). Subjects who perceived that it was safe to smoke for one or two years were more likely to smoke than those who thought it was definitely not safe to do so. There was a dose-response relationship between age and the amount of money available to the respondents on one hand, and current smoking status on the other (p-value < 0.001).

Conclusion

We found that White non-Hispanic adolescents were as likely to be current smokers as American Indians but more likely to be smokers than all other racial/ethnic groups. Older adolescents, increase amounts of pocket money, and perception that smoking was not harmful to health. The racial/ethnic differences in prevalence of smoking among America youth deserve particular exploration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tobacco use is a leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality in the world [1, 2]. Tobacco-related morbidity and mortality rank high especially in developed nations where the burden of disease from communicable or infectious diseases and maternal mortality is lower than in the developing nations of the world. Cigarette smoking causes serious illnesses among an estimated 8.6 million persons and approximately 440,000 deaths annually in the United States [3]. The prevalence of adult cigarette smoking in the United States has slightly decreased since the early 1990s from 24.7% in 1997 to 20.8% in 2006 [4, 5]. This lack of a further decrease in cigarette use during this period might have been due to cuts in funding for comprehensive state programs for tobacco control and prevention by 20.3% from 2002 to 2006 while the tobacco-industry marketing expenditures nearly doubled from 1998 ($6.7 billion) to 2005 ($13.1 billion) [5, 6].

Many of adult smokers start smoking as adolescents or young adults [7, 8]. It is therefore imperative to prevent initiation of and maintenance of smoking among adolescents. Adolescent smoking is also associated with other unhealthy behaviors such as unsafe sexual intercourse [9, 10], alcohol use [11, 12] and truancy [13]. Cigarette smoking has also been described as a "gateway" substance towards illicit drug use among adolescents and young adults [14, 15]. Prevention of adolescent smoking therefore potentially has short term as well as long-range benefits. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has used data on the prevalence of cigarette smoking among adolescents as an indicator of future burden of chronic disease in the country. Internationally, much of the data on global adolescent tobacco use come from the Global Youth Tobacco Survey [16–20].

The prevalence of tobacco use among in-school adolescents in the US using the 2004 National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS) have been reported before [21]. However this report did not assess factors that are associated with smoking in this group. We therefore used data from the United States to conduct further analyses to assess whether the following factors are associated with smoking among adolescents in the US: age; ethnicity; living with smoker in the same household; perception that it is alright to smoke for one to two years as long as one stops thereafter; smoking in best friends and the amount of pocket money at the disposal of the adolescent.

Methods

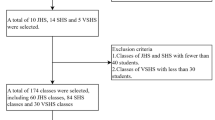

This study was based on secondary analysis of the NYTS of 2004. A comprehensive description of the survey has been reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [21, 22]. Of the 31,774 students who were eligible to participate in the study, 27,933 (88%) completed the survey (14,034 middle school students [grades 6–8], 13,738 high school students [grades 9–12], and 161 students unclassified with respect to grade).

Data were weighted with the intention to adjust for design effects (non-independence) resulting from sampling within clusters in order to produce estimates that should be nationally representative. SUDAAN version 9.0 (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, USA) was used for data analysis. Prevalence of current smoking and selected relevant socio-demographics were obtained. Current smoking was defined as having smoked a cigarette at least once in the last 30 days. Bivariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses were conducted to assess factors that are associated with current cigarette smoking. The explanatory variables that were assessed are: age; ethnicity; living with smoker; perception that it is alright to smoke for one to two years as long as one stops thereafter; smoking in best friends and the amount of pocket money at the disposal of the adolescent. For the purpose of these analyses, complete data were available for 27,727 study participants.

Results

Characteristics of the study participants

Data for 27,727 students who participated in the study were analyzed of whom 13,958 (50.4%) were males and 13,769 (49.6%) were females. The median age was 14 years (Q1 = < 16 years, Q3 = 13 years).

Prevalence of cigarettes smoking

Table 1 indicates that of the 27,727 participants, 15.9 males and 15.3% females reported being current cigarette smokers. Whites had the highest rate of smoking (17.6%) while Asians had the lowest (9.3%).

Factors associated with being a current cigarette smoker

Table 2 indicates that for both males and females, age and ethnicity, living with a cigarette smoker, having best friends cigarette smokers, perception that it is safe to smoke for only a year or two, and pocket money were associated with current cigarette smoking.

Table 3 indicates that findings from multivariate analysis remained unchanged. Compared to Whites, respondents from almost all ethnic groups were less likely to report current cigarette smoking: Blacks (OR = 0.52; 95% CI [0.44, 0.60]), Asians (OR = 0.45; 95% CI [0.35, 0.58]), Hispanic (OR = 0.81; 95% CI [0.71, 0.92]), and Hawaii/Pacific Islanders (OR = 0.69; 95% CI [0.52, 0.93]). American Indians were equally likely to be current smokers as whites, OR = 0.98 [95% CI; 0.79, 1.22].

Participants who reported living with a smoker were more than twice as likely to smoke as those who did not live with a cigarette smoker (OR = 2.73; 95% CI [2.21, 3.04]). Having friends who smoked was positively associated with smoking (OR = 2.27; 95% CI [1.91, 2.71] for one friend who smoked, and OR = 2.71; 95% CI [2.21, 3.33] for two or more friends who smoked). Subjects who perceived that it was safe to smoke for one or two years were more likely to smoke than those who thought it was definitely not safe to do so. There was a close-response relationship between age, and the amount of money available to the respondents on one hand and smoking on the other (p-value < 0.001).

Discussion

We report in the current study an overall prevalence of current cigarette smoking among the studied cohort in 2004 of 15.7%, with lower smoking rates at lower ages from 4.0% in those 12 years old or younger to 25.7% in those 16 years or older. Males predominated in being smokers as has been shown in other studies [23–25]. However, in absolute terms, the difference in prevalence was rather minimal, 15.9% and 15.3% in males and females respectively. Our study also found that having a close friend who was a smoker, or living in a household with a smoker were both independently associated with being a current smoker among the adolescents. Previous studies have reported similar correlation between these characteristics and smoking [26–28].

In a prospective study on adolescent alcohol drinking reported by Fisher et al [29], having adults who drink in the home, underage sibling who drinks, peer who drinks, possession of or willingness to use alcohol promotional items, and positive attitudes toward alcohol were associated with an increased likelihood of alcohol initiation. The mechanisms operating in the case of alcohol i.e. role modeling, acceptability of a behavior within the home and among siblings and peers, easy access to a substance and positive attitude towards a behavior, may be operational in the case of smoking.

Due to the cross sectional nature of the data collection in the NYTS, it is not possible to ascribe causation or determine the exact sequence of events in an adolescents' smoking trajectory. It is plausible to consider that adolescents who befriend smokers are more likely to be influenced into smoking. It is equally plausible that adolescents who smoke are more likely to choose other smokers as their friends [30, 31]. Adult smokers within the home are also less likely to discourage adolescents from smoking. Furthermore the easy availability of cigarettes when other people are smokers in the home may facilitate initiation and maintenance of smoking among the adolescents. Conley Thomson et al [32] have reported that household smoking bans limits smoking among adolescents. Adults who do not smoke themselves are more likely to discourage smoking in the home and elsewhere than smokers. This study also found that as age increases, the likelihood of being a current smoker also increases.

We also found that white-non Hispanic adolescents were more likely to be smokers than African-American, Asian-Americans and Hispanic. American Indians however were as likely as Whites to be smokers. We did not determine why this may be the case from the available data. However, a literature review report by Tauras [33] found that Hispanics and African Americans were more responsive to changes in cigarette prices than whites. Furthermore, one study that was reviewed reported that adolescent white males who smoked were responsive to changes in smoke-free air laws, while adolescent blacks who smoked were responsive to changes in youth access laws. This may suggest that different racial/ethnic groups may respond to different public health interventions.

In agreement to previous studies [23, 24], perception that smoking was not harmful to health and having pocket money were associated with being a current smoker among adolescents. In an environment where adolescents may be legally employed to earn income from employment, it is possible that much of an adolescent's income may not be coming from parents. As such expecting parental supervision on adolescent spending may be particularly difficult. Also, it is possible that the amount of pocket money available to the adolescent may have just been a surrogate variable for the unmeasured time that the adolescent spends at work. Ramchand et al [34] have reported that the longer the hours an adolescent worked, the more likely she or he was to be a smoker.

Overall, 1 in 10 adolescents in the current study thought smoking was "cool", 1 in 3 owned an item with a tobacco brand, and exposure to pro-tobacco advertisements at gas stations, on the internet and smoking by characters in movies/television exceeded 40%. This amount of exposure should be seen in the light of evidence that media exposure to tobacco advertisements is associated with adolescent smoking [35–37].

Limitations of the study

This study had several limitations. First, the results reported in this study were based on self-reports. Study participants may have intentionally mis-reported history of smoking or done so inadvertently. In addition, the levels of reliability and validity in the specific settings where data collection occurred may result in differential bias. Furthermore, self-reported history of smoking was not validated with laboratory markers such as exhaled carbon monoxide, and blood or urine cotinine [38–40]. Brener et al [41] however have reported high reliability of this methodology to assess adolescent health risky behaviors. However, in the design and administration of the surveys, various steps were taken to mitigate such bias, for example students were participated anonymously. This was aimed to prevent intentional mis-reporting for fear of reprisals from school officials. However, it is not possible to gauge how far the study participants completed the questionnaires as accurately as possible.

Smoking rates among students who were habitually absent may have been different from the rates among their counterparts who attended school regularly. The external validity of the results from the current study may therefore be limited to students who were not absent on the day of administration. It is however likely that absent students are more likely to be smokers than those present in schools [42, 43], so our findings are likely to be underestimates.

Among persons aged 16 or 17 years in the United States, about 5% were not enrolled in a high school education and had not completed high school in 2000 [44]. The questionnaire was offered only in English, and so with the increase in non-US born adolescents who may have difficulties in comprehension, there may have been misreporting. Finally, the factors assessed in this study were limited to socio-demographic variables. Key psychosocial variables known to affect substance use such as perceived norms, outcome expectancies, ability to resist peer appeals (self-efficacy), depression, truancy and stress were not included.

Conclusion

We found that White non-Hispanic adolescents were as likely to be current smokers as American Indians but more likely to be smokers than all other racial/ethnic groups. Older adolescents, increase amounts of pocket money and perception that smoking was not harmful to health were associated with being a smoker. There is need to explore the reasons why the prevalence of smoking among difference racial groups differ in United States.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations

- GYTS:

-

Global Youth Tobacco Survey

- YRBS:

-

Youth Risk Behavior Survey

- NYTS:

-

National Youth Tobacco Survey

- US:

-

United States.

References

Mannino DM, Buist AS: Global burden of COPD: risk factors, prevalence, and future trends. Lancet. 2007, 370: 765-73. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61380-4.

Warren CW, Jones NR, Eriksen MP, Asma S, Global Tobacco Surveillance System (GTSS) collaborative group: Patterns of global tobacco use in young people and implications for future chronic disease burden in adults. Lancet. 2006, 367: 749-53. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68192-0.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Cigarette smoking-attributable morbidity...United States, 2000. MMWR. 2003, 52: 842-4.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Annual smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and economic costs–United States, 1995–1999. MMWR. 2002, 51: 300-3.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Cigarette smoking among adults–United States, 2006. MMWR. 2007, 56: 1157-61.

Fagan P, Brook JS, Rubenstone E, Zhang C, Brook DW: Longitudinal precursors of young adult light smoking among African Americans and Puerto Ricans. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009, 11: 139-47. 10.1093/ntr/ntp009.

White H, Pandina R, Chen P: Developmental trajectories of cigarette use from early adolescence into young adulthood. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002, 65 (2): 167-178. 10.1016/S0376-8716(01)00159-4.

Dearden KA, Crookston BT, De La Cruz NG, Lindsay GB, Bowden A, Carlston L, Gardner P: Teens in trouble: cigarette use and risky behaviors among private, high school students in La Paz, Bolivia. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2007, 22: 160-8. 10.1590/S1020-49892007000800002.

Aras S, Semin S, Gunay T, Orcin E, Ozan S: Sexual attitudes and risk-taking behaviors of high school students in Turkey. J Sch Health. 2007, 77: 359-66. 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00220.x.

Faeh D, Viswanathan B, Chiolero A, Warren W, Bovet P: Clustering of smoking, alcohol drinking and cannabis use in adolescents in a rapidly developing country. BMC Public Health. 2006, 6: 169-10.1186/1471-2458-6-169.

White HR, Violette NM, Metzger L, Stouthamer-Loeber M: Adolescent risk factors for late-onset smoking among African American young men. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007, 9: 153-61. 10.1080/14622200601078350.

Brook JS, Balka EB, Ning Y, Brook DW: Trajectories of cigarette smoking among African Americans and Puerto Ricans from adolescence to young adulthood: associations with dependence on alcohol and illegal drugs. Am J Addict. 2007, 16: 195-201. 10.1080/10550490701375244.

White HR, Jarrett N, Valencia EY, Loeber R, Wei E: Stages and sequences of initiation and regular substance use in a longitudinal cohort of black and white male adolescents. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007, 68: 173-81.

Khan MM, Aklimunnessa K, Kabir MA, Kabir M, Mori M: Tobacco consumption and its association with illicit drug use among men in Bangladesh. Addiction. 2006, 101: 1178-86. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01514.x.

Biederman J, Monuteaux MC, Mick E, Wilens TE, Fontanella JA, Poetzl KM, Kirk T, Masse J, Faraone SV: Is cigarette smoking a gateway to alcohol and illicit drug use disorders? A study of youths with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2006, 59: 258-64. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.07.009.

Baska T, Sovinová H, Nemeth A, Przewozniak K, Warren CW, Kavcová E, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia GYTS Collaborative Group: Findings from the Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) in Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia–smoking initiation, prevalence of tobacco use and cessation. Soz Praventivmed. 2006, 51: 110-6. 10.1007/s00038-005-0022-8.

Kyrlesi A, Soteriades ES, Warren CW, Kremastinou J, Papastergiou P, Jones NR, Hadjichristodoulou C: Tobacco use among students aged 13–15 years in Greece: the GYTS project. BMC Public Health. 2007, 7: 3-10.1186/1471-2458-7-3.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Use of cigarettes and other tobacco products among students aged 13–15 years–worldwide, 1999–2005. MMWR. 2006, 55: 553-6.

Global Youth Tobacco Survey Collaborating Group: Differences in worldwide tobacco use by gender: findings from the Global Youth Tobacco Survey. J Sch Health. 2003, 73: 207-15.

Sovinová H, Csémy L: Smoking behaviour of Czech adolescents: results of the Global Youth Tobacco Survey in the Czech Republic, 2002. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2004, 12: 26-31.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Tobacco Use, Access, and Exposure to Tobacco in Media Among Middle and High School Students – United States, 2004. MMWR. 2005, 54: 297-301.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: 2004, National Youth Tobacco Survey. Methodology Report. Contract Number: 2003-Q-00775. 2009, Office on Smoking and Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, United States of America, Retrieved 20 12 February 2009, [http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/surveys/nyts/index.htm#NYTS2004]

Siziya S, Muula AS, Rudatsikira E: Correlates of current cigarette smoking among in-school adolescents in the Kurdistan region of Iraq. Confl Health. 2007, 1: 13-10.1186/1752-1505-1-13.

Siziya S, Rudatsikira E, Muula AS, Ntata PR: Predictors of cigarette smoking among adolescents in rural Zambia: results from a cross sectional study from Chongwe district. Rural Remote Health. 2007, 7: 728-

Jindal SK, Aggarwal AN, Gupta D, Kashyap S, Chaudhary D: Prevalence of tobacco use among school going youth in North Indian States. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2005, 47: 161-6.

Rachiotis G, Muula AS, Rudatsikira E, Siziya S, Kyrlesi A, Gourgoulianis K, Hadjichristodoulou C: Factors associated with adolescent cigarette smoking in Greece: results from a cross sectional study (GYTS Study). BMC Public Health. 2008, 8: 313-10.1186/1471-2458-8-313.

Rudatsikira E, Muula AS, Siziya S, Mataya RH: Correlates of cigarette smoking among school-going adolescents in Thailand: findings from the Thai global youth tobacco survey 2005. Int Arch Med. 2008, 1: 8-10.1186/1755-7682-1-8.

Rudatsikira E, Abdo A, Muula AS: Prevalence and determinants of adolescent tobacco smoking in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2007, 7: 176-10.1186/1471-2458-7-176.

Fisher LB, Miles IW, Austin SB, Camargo CA, Colditz GA: Predictors of initiation of alcohol use among US adolescents: findings from a prospective cohort study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007, 161: 959-66. 10.1001/archpedi.161.10.959.

Chassin L, Presson CC, Sherman SJ: Cognitive and social influence factors in adolescent smoking cessation. Addict Behav. 1984, 9: 383-90. 10.1016/0306-4603(84)90038-8.

Wang MQ, Eddy JM, Fitzhugh EC: Smoking acquisition: peer influence and self-selection. Psychol Rep. 2000, 86: 1241-6. 10.2466/PR0.86.3.1241-1246.

Conley Thomson C, Siegel M, Winickoff J, Biener L, Rigotti NA: Household smoking bans and adolescents' perceived prevalence of smoking and social acceptability of smoking. Prev Med. 2005, 41: 349-56. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.12.003.

Tauras JA: Differential impact of state tobacco control policies among race and ethnic groups. Addiction. 2007, 102 (Suppl 2): 95-103. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01960.x.

Ramchand R, Ialongo NS, Chilcoat HD: The effect of working for pay on adolescent tobacco use. Am J Public Health. 2007, 97: 2056-62. 10.2105/AJPH.2006.094045.

Ling PM, Glantz SA: Why and how the tobacco industry sells cigarettes to young adults: evidence from industry documents. Am J Public Health. 2002, 92: 908-16. 10.2105/AJPH.92.6.908.

Borzekowski DL, Flora JA, Feighery E, Schooler C: The perceived influence of cigarette advertisements and smoking susceptibility among seventh graders. J Health Commun. 1999, 4: 105-18. 10.1080/108107399126995.

Wills TA, Sargent JD, Stoolmiller M, Gibbons FX, Worth KA, Cin SD: Movie exposure to smoking cues and adolescent smoking onset: a test for mediation through peer affiliations. Health Psychol. 2007, 26: 769-76. 10.1037/0278-6133.26.6.769.

Hung J, Lin CH, Wang JD, Chann CC: Exhaled carbon monoxide level as an indicator of cigarette consumption in a workplace cessation program in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2006, 105: 210-3.

Jenkins RA, Counts RW: Personal exposure to environmental tobacco smoke: salivary cotinine, airborne nicotine, and nonsmoker misclassification. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 1999, 9: 352-63. 10.1038/sj.jea.7500036.

Low EC, Ong MC, Tan M: Breath carbon monoxide as an indication of smoking habit in the military setting. Singapore Med J. 2004, 45: 578-82.

Brener ND, Collins JL, Kann L, Warren CW, Williams BI: Reliability of the Youth Risk Behavior Survey Questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol. 1995, 141: 575-80.

Gage AJ, Suzuki CJ: Risk factors for alcohol use among male adolescents and emerging adults in Haiti. J Adolesc. 2006, 29: 241-60. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.05.001.

Yang G, Ma J, Chen AP, Brown S, Taylor CE, Samet JM: Smoking among adolescents in China: 1998 survey findings. Int J Epidemiol. 2004, 3: 1103-10. 10.1093/ije/dyh225.

US Department of Education: Dropout rates in the United States: 2000. 2001, Washington, DC. US Department of Education, National Center for Educational Statistics, Office of Educational Research and Improvement, publication no. (NCES) 2002–114

Acknowledgements

Data used in this study were obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office on Smoking and Health National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion to which we are immensely grateful. We also thank the students, parents and school administrators for making the data collection exercise possible.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

ER: conceived data analysis plan, conducted data analysis, and participated in the drafting of the manuscript. AM: participated in the interpretation of the results and drafting of the manuscript. SS: participated in the interpretation of the results and drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Rudatsikira, E., Muula, A.S. & Siziya, S. Current cigarette smoking among in-school American youth: results from the 2004 National Youth Tobacco Survey. Int J Equity Health 8, 10 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-8-10

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-8-10