Abstract

Introduction

Addressing the underrepresentation of indigenous health professionals is recognised internationally as being integral to overcoming indigenous health inequities. This literature review aims to identify 'best practice' for recruitment of indigenous secondary school students into tertiary health programmes with particular relevance to recruitment of Māori within a New Zealand context.

Methodology/methods

A Kaupapa Māori Research (KMR) methodological approach was utilised to review literature and categorise content via: country; population group; health profession ffocus; research methods; evidence of effectiveness; and discussion of barriers. Recruitment activities are described within five broad contexts associated with the recruitment pipeline: Early Exposure, Transitioning, Retention/Completion, Professional Workforce Development, and Across the total pipeline.

Results

A total of 70 articles were included. There is a lack of published literature specific to Māori recruitment and a limited, but growing, body of literature focused on other indigenous and underrepresented minority populations.

The literature is primarily descriptive in nature with few articles providing evidence of effectiveness. However, the literature clearly frames recruitment activity as occurring across a pipeline that extends from secondary through to tertiary education contexts and in some instances vocational (post-graduate) training. Early exposure activities encourage students to achieve success in appropriate school subjects, address deficiencies in careers advice and offer tertiary enrichment opportunities. Support for students to transition into and within health professional programmes is required including bridging/foundation programmes, admission policies/quotas and institutional mission statements demonstrating a commitment to achieving equity. Retention/completion support includes academic and pastoral interventions and institutional changes to ensure safer environments for indigenous students. Overall, recruitment should reflect a comprehensive, integrated pipeline approach that includes secondary, tertiary, community and workforce stakeholders.

Conclusions

Although the current literature is less able to identify 'best practice', six broad principles to achieve success for indigenous health workforce development include: 1) Framing initiatives within indigenous worldviews 2) Demonstrating a tangible institutional commitment to equity 3) Framing interventions to address barriers to indigenous health workforce development 4) Incorporating a comprehensive pipeline model 5) Increasing family and community engagement and 6) Incorporating quality data tracking and evaluation. Achieving equity in health workforce representation should remain both a political and ethical priority.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Indigenous1 populations worldwide experience significant inequities in healthcare access, healthcare quality and ultimately health outcomes with persistent disparities observed in life expectancy, morbidity and mortality when compared to non-indigenous populations [1, 2]. Addressing the underrepresentation of indigenous health professionals is recognised internationally as being an integral component of the overall response to overcoming indigenous health inequities [3]. However, indigenous students face significant barriers to participation and success in health education and understanding how to best achieve indigenous health workforce development remains a challenge.

This article explores the international literature for evidence of 'best-practice' for the recruitment of Māori (the indigenous population of New Zealand) or indigenous secondary students into health careers. Whether 'best practice', a contentious and potentially value-laden term, can actually be identified for Māori or indigenous students is an additional area of investigation for this study [4].

In New Zealand, Māori are under-represented within frontline health professional roles [5–7] (Table 1). The indigenous health workforce shortage in New Zealand is critical, with New Zealand having the largest proportion of overseas trained doctors internationally [8]. Evidence suggests that a lack of cultural concordance between patients and health professionals [9] may reduce patient satisfaction, access and adherence to treatments [10, 11].

Therefore, under-representation of indigenous peoples within health professions reduces the potential of the health sector to provide a diverse, capable and culturally appropriate workforce that meets the needs of indigenous communities [12]. Similarly, the rights of indigenous peoples to equitable access to the opportunities of society, including the personal and community benefits of health workforce development and improving health outcomes may not be fully realised if such disparities continue [13–16].

There are multiple explanations for the shortage of indigenous health professionals reflecting a mixture of supply and demand issues associated with historical, political, demographic, cultural, academic and financial factors [17–23]. Initiatives aimed at increasing the recruitment of secondary school students into health careers are increasingly being funded by government agencies as a key mechanism to attract more indigenous students into what are often rigorous and demanding academic pathways [24, 25]. At present, health recruitment initiatives in New Zealand tend to focus on making health careers 'attractive' to adolescents and are largely based within the secondary school sector. Recruitment programmes have only recently increased the focus on supporting indigenous secondary school students to achieve in the appropriate (e.g. science) subjects required for entry into health professional programmes.

A pipeline framework is commonly utilised to discuss health recruitment activity (Figure 1) [3, 26].

The Sullivan Commission report [27] notes that 'a pipeline from primary to secondary to postsecondary education, and finally to professional training, channels the flow of a diverse and talented stream of individuals into the nation's health care workforce' (p. 72). However, exactly what specific components are most effective and efficient, where they should be provided and how recruitment should be occurring within this pipeline remains unclear [13]. Furthermore, lessons can be learnt from other countries attempting similar (or different) approaches to the production of indigenous health professionals. This literature review considers broad recruitment contexts that may inform the health sector on how best to recruit indigenous secondary school students into health careers. Framed from a New Zealand context with a particular focus on Māori student recruitment, it is expected that the findings will have relevance internationally for other institutions hoping to address similar issues.

Research design

Aim

The aim of this literature review is to identify national and international evidence of best practice for recruitment of Māori or indigenous secondary school students into health related tertiary programmes.

Methodology

A Kaupapa Māori Research (KMR) [28] methodological approach was utilised. KMR is based on a number of key principles [29]. In this instance it aims to provide: a critique of literature from a Māori paradigm that takes into account the structural and power imbalances within society that perpetuate inequities; an explicit challenge to or rejection of 'victim blame' and 'cultural deficit' analyses [30]; a commitment to ensuring that the research outputs will have positive benefits for Māori communities; a commitment to Māori, research leadership and workforce development. Such an approach involves questioning conclusions that require students to change their behaviour rather than the recruitment programme, inclusion of non-published but highly relevant Māori literature, acknowledging the relevance of other indigenous and under-represented minority population literature whilst maintaining a focus on Māori as indigenous peoples in the New Zealand context, rejection of findings that suggest the culture of Māori students is to blame for their educational failures and ensuring that any recommendations made from the review aim to facilitate Māori student success.

Data sources

Literature were initially identified via searches within three sources: (1) Medline (Ovid) database, (2) ERIC database and (3) grey literature (unpublished documents or reports highly relevant to the aim).

Initial searches specific to Māori or other indigenous populations (i.e. Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander, Native American, Inuit, Metis or First Nation peoples) produced very few results. The search was therefore widened to include Pacific (i.e. the heterogeneous composite of Pacific ethnic minority groups living in New Zealand e.g. Samoan, Tongan, Nuiean, Cook Island), however this also provided only a small number of articles. Given this context, the research team decided that the literature search would extend to under-represented minority groups or URM. 2 Data on URM students have been included as their situations, statistics and challenges often mirror those of indigenous students. Furthermore, issues associated with power, privilege and agency within society are hypothesised to be similar for indigenous and URM groups and therefore exploring the literature for these groups collectively was thought to be appropriate given the small amount of data currently available. The term indigenous/URM is used when discussing the actual literature review findings with specific reference to Māori where appropriate.

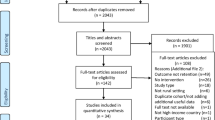

Key search words included: 'Māori', 'Indigenous', 'Aboriginal', 'Minority', 'Ethnic', 'Race', Disadvantaged', 'Underrepresented', 'Recruit*', 'Secondary', 'Tertiary', 'Undergraduate', 'School', 'Student', 'Education', 'Programme', 'Health', 'Science', 'Careers', 'Selection', 'Transition', 'Retention', 'Admission', 'Best Practice', 'Intervention'. A total of 216 articles from Medline and 202 articles from ERIC were initially identified using various combinations of these key words. All abstracts were reviewed and articles were excluded using the following criteria: published before 1985; not specifically relevant to the stated aim; not in English language; could not be obtained in hard copy. Application of the above criteria resulted in 172 Medline and 195 ERIC articles being excluded. A total of 70 articles sourced from Medline (44), ERIC (7) and Grey Literature (19) remained for inclusion in this literature review [5, 6, 12, 14, 17, 18, 20–22, 25, 26, 31–90].

Analysis

All data (hereon referred to as 'articles') were reviewed and article content was categorised via the following variables: country; population group; health profession focus; research methods; evidence of effectiveness; and discussion of barriers (Table 2). Recruitment activities were categorised into five broad contexts associated with the recruitment pipeline (Table 3). The potential overlap of activities between these broad contexts is acknowledged, however, the following definitions have guided this literature review: (1) early exposure (i.e. activities targeted towards secondary school students that aim to expose students to health careers and academic pathways), (2) transitioning (i.e. activities that assist secondary school students to enter tertiary study programmes), (3) retention/completion (i.e. activities that aim to support success in tertiary health professional programmes), (4) professional workforce development (i.e. activities that aim to develop the existing health workforce including continuous professional development, specialisation or career development) and (5) across the total pipeline (i.e. activities that occur in more than one aspect of the pipeline).

Results

Literature focus

Table 4 provides a synopsis of the specific recruitment activities occurring within these five contexts. A summary of the content associated with each article based on the variables and contexts identified above is provided in Table 5.

The majority of articles are sourced from the United States of America (USA) (37/70), followed by Australia (15/70) and New Zealand (13/70) with only a small number of articles obtained from the United Kingdom (3/70) and Canada (2/70). Most articles referred to Under Represented Minority (37) population groups with 24 articles specific to Indigenous population groups. A smaller number of articles were identified if they specifically referred to Māori (12) and Pacific (11) population groups. Health profession areas of focus include medicine (40), followed by nursing/midwifery (31), dentistry (24), allied health professions (20) and pharmacy ( 11).

The majority of articles are descriptive in nature (55). Thirty-four articles provide some evidence and/or analysis of tertiary student data. Twenty-four articles involved surveys of students, families, programme and/or university staff with a smaller number of sources presenting findings from interviews (14), focus groups (11) and workshop/seminars (10).

Of the 70 articles, 42 sources provide new evidence of effectiveness regarding the recruitment activities described. Of these, 35 sources discuss the appropriateness of the process of recruitment, 26 sources present evidence of promising workforce outcomes (e.g. matriculation/enrolment into health programmes) and 10 present evidence of workforce achievement (e.g. completion/graduation from health programmes).

Literature content

Nearly three quarters of the articles present their findings within the context of a pipeline that integrates recruitment across both the secondary and tertiary education sectors (51/70) compared to articles that have a specific focus on either secondary education (7/70) or tertiary education (12/70). Overall, there is a similar amount of evidence that refers to recruitment activities within early exposure (59/70), transitioning (47/70), retention/completion (60/70) and those activities that occur across the total pipeline (66/70). A small number of articles discuss the importance of professional workforce development (12/70) within the recruitment pipeline; however, these articles are not the key focus of this literature review, and therefore a more extensive literature review focused on professional workforce development is required to examine this aspect of the pipeline further.

Early exposure

Early exposure interventions focused on school visits, provision of additional academic preparation and targeted secondary enrichment programmes where students are provided with opportunities to visit tertiary institutions and health settings. Improving advice from careers advisors, including parental involvement and advertising/marketing to support career decision making were highlighted. A small number of USA articles referred to the provision of secondary financial support to students whilst studying at secondary school.

Transitioning

Admission/quota policies targeted towards indigenous and URM students and the offering of tertiary enrichment programmes to undergraduate students seeking post-graduate entry into health training were well described. Student pre-matriculation/application support and the provision of bridging/foundation programmes to address academic prerequisite gaps (particularly within the science subjects) were other key transitioning activities.

Retention/completion

Tertiary retention and completion activities included the provision of specific support programmes and the need to develop staff/faculty with a particular focus on indigenous and URM academic leadership. Retention activities referred to the provision of tertiary financial support and a commitment to indigenous/URM curriculum development. The provision of accommodation support and the options of first year expansion particularly within medical programmes were discussed in a smaller number of articles.

Across the pipeline

A number of activities occur across the total pipeline and are used within secondary, transitioning and tertiary contexts including the use of indigenous and URM role models, mentoring and ensuring community involvement in recruitment activities. Facilitating access for secondary and tertiary students to obtain health work experience is encouraged. Some articles specifically noted the need to conduct ongoing evaluation/tracking, research, inclusion of spiritual/cultural values within the recruitment process and the presence of a tertiary mission statement/vision.

Discussion

This study reviewed 70 articles to explore national and international best practice for recruitment of Māori or indigenous/URM secondary school students into health related tertiary programmes. The following discussion explores key issues relevant to the recruitment pipeline in total and within the specific contexts of early exposure, transitioning, retention/completion.

Early exposure

The literature identifies a number of barriers for indigenous/URM secondary school students wishing to pursue health careers. These barriers reflect education, information, aspiration and access issues requiring the development of appropriate interventions within the early exposure context.

For example, within the New Zealand context, inequities in academic achievement rates between Māori and non-Māori secondary school students, particularly within science subjects, are a major barrier underlying the need for early exposure. In 2007 nearly two out of five Māori aged ≥ 15 years had no formal qualification and participation in a Year 133 science subject was only 23% for Māori secondary school students compared to 41% for non-Māori [91]. In 2009, only 29% Māori versus 54% non-Māori students received university entrance at the completion of their final year of secondary school study [92, 93]. Similar academic achievement inequities exist internationally and therefore interventions that encourage indigenous students to choose the appropriate prerequisite subjects at secondary school such as sciences (i.e. Chemistry, Biology, and Physics) and other relevant subjects are needed (e.g. English and Mathematics) [19, 71, 83, 84]. Once students have chosen the right subjects, appropriate support should be provided to ensure indigenous students attain the necessary credits for entry into health programmes [27, 83]. Early exposure must therefore ensure that secondary school students have access to the necessary academic building blocks for movement into health professional programmes.

The literature also discusses the importance of actively including parents, families and indigenous/URM communities in early exposure activities due to their influence on student career choices [13, 19, 37, 60, 78, 83, 90]. This is particularly important as indigenous/URM students are often diverted away from health careers via careers advisors and teachers [18, 19]. For example, Chesters et al. [35] found that only 18% (26/144) of secondary school advisors or guidance counsellors were able to demonstrate the knowledge required to effectively advise or support indigenous students into health careers. Similar findings are described elsewhere [18, 19, 27, 44, 60, 64, 74, 78, 83] with Hollow et al. [44] noting "when counsellors or teachers "track" minority [or indigenous] students into less rigorous academic courses - intentionally or not - they limit student's academic achievement and inhibit their career aspirations"(p. 4).

Addressing the deficit or failure discourse of career advisors via professional development [35] and, more importantly, supporting the use of indigenous/URM staff, role models or mentors to provide careers advice is recommended [21, 44, 83, 94].

Other enrichment activities such as visits to tertiary institutions that expose indigenous/URM students to campus environments early [17, 70, 71, 95] are recommended. These enrichment activities are important as they introduce students to indigenous/URM role models they may not have had access to previously [47, 56, 67, 82], they foster trust between tertiary providers and families/communities [47, 56] and enhance student confidence and motivation to apply for health programmes [42].

Transitioning

Indigenous/URM students face significant barriers when transitioning into tertiary programmes. While many students entering university have to leave their families, communities and support networks; indigenous/URM students have the additional pressure of entering into what is generally a non-indigenous/URM, foreign and unfriendly tertiary environment [18, 51, 96]. Madjar et al. [96] discuss the large size of first year degree lectures as contributing to student's feelings of isolation [96], with indigenous/URM students often feeling 'culturally alienated' (p. 1049) within the tertiary environment [97]. Indigenous/URM specific orientations may therefore create a more welcoming and indigenous/URM appropriate introduction to tertiary settings [17, 41, 71].

Indigenous/URM students experiencing academic barriers to programme entry (often complicated with additional pastoral and socio-economic issues) [13, 95] may be best supported by a bridging/foundation programme. To achieve this comprehensive support, bridging/foundation programmes differ according to their duration (from 4-6 weeks to an academic year), content focus (individualised to a specific student versus generic programme provision) and cohort size (from 6 students to over 100 students) [95, 98] and are often designed for their local contexts. Many utilise indigenous/URM curriculum content (e.g. Aboriginal health topics) [13, 61, 74, 96], specifically support the acquisition of study skills required for tertiary study [71, 86], whilst also ensuring that students are given access to indigenous/URM role models for motivation to continue along the pathway towards health careers [13, 48]. Bridging/foundation programmes therefore have the potential to provide comprehensive transitioning support to address gaps in educational achievement whilst also ensuring that students are set up for success from a pastoral perspective.

Tertiary institutions should demonstrate a tangible commitment to equity initiatives via the provision of well defined, accessible and targeted admission policies or quotas for indigenous students. Support to navigate the often complex university application processes should also be provided [81]. These activities not only create direct pathways for indigenous/URM student entry, they also promote the institution as valuing cultural diversity which has been identified as being attractive for indigenous/URM students considering health as a career [17, 31].

It is acknowledged that transitioning in a broader context occurs at multiple sites along the pipeline whenever students move between environments within the education sector (e.g. secondary to tertiary, undergraduate students into graduate health study). Therefore institutions may need to provide multiple forms of transitioning support beyond the definition outlined within this literature review [27, 96].

Retention/completion

Inequities in academic achievement for indigenous/URM students persist into the tertiary context. New Zealand statistics for example, show that national participation rates for Māori aged 18-19 in degree level study is less than half the rate for all students, Māori first year attrition rates in bachelor degree level programmes are 28.8% versus 18.2% for non-Māori [99, 100] and Māori rates of participation in health professional degree level programmes remain low [101]. This data supports the need for successful recruitment programmes to extend beyond getting students into programmes and provide indigenous students with comprehensive retention and completion support within the tertiary context [17, 18, 73].

Similar to other educational settings [102], support for indigenous/URM students within health professional programmes should include academic interventions such as additional tutorials [69, 84], study support [84] and formation of study groups [21, 64]. Pastoral interventions should also be provided to facilitate student access to financial assistance (a pivotal support requirement) [54, 69, 86, 90], referral to counseling as required [51, 80, 84] and provision of ongoing career advice [51, 69]. Tertiary institutions need to provide the resources to support retention activities including the provision of culturally safe spaces for indigenous students [51, 69]. Having access to an indigenous/URM specific space encourages peer support, provides a safe haven from any racism experienced from their non-indigenous/URM peers or institution and allows students to operate within culturally appropriate contexts (e.g. physical study spaces that include shared eating opportunities) [13, 18, 51, 83].

However, encouraging indigenous/URM students to become more resilient to unsafe environments and negative experiences within their health professional training is an inadequate response [18]. Tertiary institutions can address these issues and target student development via curriculum reform that includes both indigenous/URM and cultural safety content [17, 83]. The provision of professional development for staff to understand and address these issues is also required [17, 51, 54, 71] alongside the development of indigenous/URM academic and general staff positions [17, 18, 56] and the promotion of indigenous/URM academics to positions of tertiary leadership [56]. Whilst many of these interventions are not new to those delivering tertiary support, the framing of these interventions within a secondary school recruitment framework reflects the broader pipeline approach.

The pipeline

Debate exists around the definition and scope of 'receruitment' with some commentators suggesting that recruitment activities cease once students enter a tertiary institution [103]. However, the literature clearly frames recruitment activity as occurring across a pipeline that extends from secondary through to tertiary education contexts and in some instances vocational (post-graduate) training [13, 21, 25, 27, 74, 82, 85, 104].

Given this context, tertiary institutions have a responsibility (and arguably a requirement) to provide both secondary school recruitment and tertiary retention initiatives that target indigenous/URM students. This reflects ethical concerns that may arise if institutions actively recruit students into tertiary environments that fail to ensure indigenous student success. Similarly, recruitment programmes have a responsibility to ensure that they are knowledgeable of, and well integrated with, the tertiary sector for successful workforce development. There is little point in making health attractive to students if they have no realistic chance or pathway for entry into what are often highly competitive programmes.

Recruitment should be framed from a comprehensive and integrated pipeline perspective that has the ability to include secondary, tertiary, community and workforce stakeholders. Active inclusion of indigenous/URM communities throughout the recruitment pipeline is encouraged [19, 32, 68], with some articles highlighting the need to better incorporate indigenous spiritual and cultural practices within secondary and tertiary contexts [19, 61]. Using a specific mission statement or vision to demonstrate a commitment to equity initiatives may assist institutions to maintain support for an integrated, indigenous/URM-appropriate, recruitment approach [13, 51, 71, 85, 90].

A number of common recruitment activities operating across the pipeline are described in the literature. For example, both secondary and tertiary students are noted to benefit from exposure to indigenous/URM role models, mentors and work experience in health settings [17, 27, 35, 69]. Unfortunately, clear and detailed descriptions of these specific activities are rarely provided and therefore assume a common understanding. 'Mentoring' for example, can be delivered both formally and informally, and may involve student peers, staff or health professionals [105]. Understanding exactly what programmes mean by mentoring is important as different models will have different protocol and resourcing implications.

Given the limited evidence of effectiveness obtained from this literature review, recruitment programmes and tertiary institutions need to improve data tracking and research potential to better inform recruitment initiatives [69]. New Zealand in particular needs to increase its contribution to the published literature in order to better present and examine the numerous recruitment strategies targeted at Māori students.

Strengths and limitations

This study highlights the lack of published literature specific to Māori recruitment and the limited, but growing, body of literature focussed on other indigenous and under-represented minority populations. The majority of articles refer to URM groups, are based in the USA and tend to focus on medicine, nursing/midwifery and dentistry. Generalisation of these findings to other settings such as indigenous students, the New Zealand context and broader health professions may be problematic. Nevertheless, it remains important to consider these programmes as models of what may (or may not) be achieved when working with populations facing similar power, privilege and agency within society and barriers to health care professional training with the proviso that adaptation to local contexts will be required.

The literature is primarily descriptive in nature with few articles providing evidence of effectiveness [17, 18, 26, 69, 73, 95]. Therefore, it is arguable that the current literature cannot fully describe 'best practice' [4]. Given this context, broad principles to inform and enhance the potential of recruitment programmes to achieve success for indigenous health workforce may be more preferable than the identification of "best practice" per se. The challenge remains to more fully understand the various components, their contributions and interactions along the recruitment pipeline, including a broader discussion of what constitutes good practice from an indigenous perspective.

It is acknowledged, that indigenous recruitment programmes are relatively new and may be less able to conduct and publish research whilst in developmental phases, particularly if there is a lack of institutional support for formal evaluation and tracking of outputs [81]. These issues need to be addressed if we are to fully understand how to best recruit and graduate indigenous students into health careers. A small number of articles described recruitment activities that targeted students within primary school settings however this requires further investigation that was outside the scope of this study.

Despite these concerns, this literature review has a number of strengths including the use of Kaupapa Māori methodology that critiques the literature from an indigenous and specifically Māori perspective; the use of a systematic review process to consider international literature as a body of evidence rather than reviewing articles in isolation; and the timeliness of reviewing the available evidence given the increasing political and health sector support for funding of indigenous health workforce development initiatives [106, 107].

Conclusions

Addressing the underrepresentation of indigenous health professionals is recognised internationally as being integral to overcoming indigenous health inequities [3, 27, 81, 107]. The literature supports the provision of indigenous specific recruitment programmes as a key initiative for indigenous health workforce development. Although the current literature is less able to identify 'best practice', six broad principles can be drawn from the literature to inform and enhance the potential of recruitment programmes to achieve success for indigenous health workforce development:

-

1.

Frame recruitment initiatives within an indigenous worldview that takes into account indigenous rights, realities, values, priorities and processes.

-

2.

Demonstrate a tangible institutional commitment to achieving indigenous health workforce equity via the development (and proactive support of) a mission statement/vision and appropriate policies and processes.

-

3.

Identify the barriers to indigenous health workforce development and use these to frame recruitment initiatives within your local context.

-

4.

Conceptualise and incorporate recruitment activity within a comprehensive and integrated pipeline model that operates across secondary and tertiary education sectors via the provision of early exposure, transitioning, retention/completion and post-graduation activities.

-

5.

Increase engagement with parents, families and indigenous communities (including tribal groups) within all recruitment activities but particularly early exposure.

-

6.

Incorporate high quality data collection, analysis and evaluation of recruitment activities within programmes with the publication of results where possible.

International institutions should apply these principles to indigenous health workforce development initiatives in a way that is meaningful, appropriate and effective within their own indigenous context. Successful indigenous health workforce recruitment has a key role to play in overcoming health inequities for indigenous peoples. Achieving equity in health workforce representation must therefore remain both a political and ethical priority.

Endnotes

1There are multiple descriptors for the term indigenous. Common themes include: those cultures whose world views place special significance on the idea of the unification of the humans with the natural world (Royal, C. (2003). Indigenous worldviews; A comparative study. Otaki, New Zealand: Te Wānanga-o-Raukawa) and descendants of those who inhabited a country or a geographical region at the time when people of different cultures or ethnic origins arrived (United Nations. (2004). The Concept of Indigenous Peoples: Background paper prepared by the Secretariat of the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. Workshop on data collection and disaggregation for Indigenous Peoples (New York, 19-21 January 2004), United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs.).

2Medical definitions for the term URM are changing over time. One definition includes "those racial and ethnic populations that are underrepresented in the medical profession relative to their numbers in the general population" (Association of American Medical Colleges. (2003). Underepresented in Medicine Definition. Retrieved from https://www.aamc.org/initiatives/urm). For the purposes of this article, URM refers to a mixture of African-American, Hispanic and/or Asian/US Pacific. Indigenous populations that may have been included within URM articles have been dually identified as indigenous for this analysis.

3Year 13 is the final year of secondary schooling in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Authors' information

Dr Elana Curtis (Te Arawa) is a specialist in public health medicine who has experience in research and policy concerned with eliminating ethnic and indigenous inequalities in health. Elana is currently employed as a Senior Lecturer and is Director of the Vision 20:20 initiative at Te Kupenga Hauora Māori, The University of Auckland. Ongoing research includes ethnic disparities in cardiovascular disease, use of Kaupapa Māori Research methodology and indigenous health workforce development.

Erena Wikaire (Ngāti Hine) is a Māori Physiotherapist who has experience in research concerned with Māori and Indigenous health workforce development, cultural competence, and psycho-oncology in Māori and Indigenous populations. Erena is currently completing a Masters in Public Health whilst working as a Researcher at Te Kupenga Hauora Māori, University of Auckland. Ongoing research interests include Māori health workforce development and addressing ethnic inequalities in health.

Kanewa Stokes (Ngāti Porou/Te Whānau ā Apanui) is the Development Manager for the Whakapiki Ake Project for recruitment of Māori into health careers within Te Kupenga Hauora Māori, The University of Auckland. Kanewa holds a Masters degree in social policy and has worked in research and evaluation across the Māori and indigenous education, health and social development sectors.

Associate Professor Papaarangi Reid (Te Rarawa) is Tumuaki and Head of Department of Māori Health at the Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, University of Auckland, New Zealand.She holds science and medical degrees from the Universities of Otago and Auckland and is a specialist in public health medicine. Her research interests include analysing disparities between indigenous and non-indigenous citizens as a means of monitoring government commitment to indigenous rights.

Abbreviations

- ERIC:

-

Education Resources Information Center

- KMR:

-

Kaupapa Māori Research

- URM:

-

Under-represented minorities

- USA:

-

United States of America.

References

Hauora: Māori Standards of Health IV. A study of the years 2000-2005. Edited by: Robson B, Harris R. 2007, Wellington: Te Rōp ū Rangahau Hauora a Eru P ō mare

Bramley D, Hebert P, Tuzzio L, Chassin M: Disparities in Indigenous Health: A Cross-Country Comparison Between New Zealand and the United States. Am J Public Health. 2005, 95 (5): 844-850. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.040907.

Ratima M, Brown R, Garrett N, Wikaire E, Ngawati R, Aspin C, Potaka U: Rauringa Raupa: Recruitment and retention of Māori in the health and disability workforce. Auckland: Taupua Waiora: Division of Public Health and Psychosocial Studies. 2008, Faculty of Health and Environmental Sciences: AUT University

Smith C, Sutton F: Best practice: What it is and what it is not. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 1999, 5 (2): 100-105. 10.1046/j.1440-172x.1999.00154.x.

Ministry of Health: He Pa Harakeke: Māori Health Workforce Profile: Selected regulated health occupations 2007. 2007, Wellington: Ministry of Health

Pharmacy Council of New Zealand: Pharmacy Council of New Zealand Workforce Demographics as at 30 June 2009. 2009, Wellington: Pharmacy Council of New Zealand

Ministry of Health: Pacific Health and Disability Workforce Development Plan. 2004, Wellington: Ministry of Health

Gorman D, Brooks P: On solutions to the shortage of doctors in Australia and New Zealand. Medical Journal of Australia. 2009, 190 (3): 152-156.

Jansen P, Bacal K, Crengle S: He Ritenga Whakaaro: Māori experiences of health services. 2008, Auckland: Mauri Ora Associates

Cooper LA, Powe NR: Disparities in patient experiences, health care processes, and outcomes: The role of patient-provider racial, ethnic, and language concordance. The Commonwealth Fund. 2004

LaVeist TA, Nuru-Jeter A, Jones KE: The Association of Doctor-Patient Race Concordance with Health Services Utilization. Journal of Public Health Policy. 2003, 24 (3/4): 312-323. 10.2307/3343378.

Health Workforce Advisory Committee: The New Zealand Health Workforce: Future Directions - Recommendations to the Minister of Health 2003. 2003, Wellington: Ministry of Health

Australian Indigenous Doctors Association: Healthy futures: Defining best practice in the recruitment and retention of Indigenous medical students. 2005, Canberra: Australian Government: Department of Health and Aging

Health Workforce Advisory Committee: Report of the Health Workforce Advisory Committee on Encouraging Māori to Work in the Health Professions. 2006, Wellington Ministry of Health

Reid P, Robson B: Understanding Health Inequities. Hauora: Māori Standards of Health IV A study of the years 2000-2005. Edited by: Robson B, Harris R. 2007, Wellington: Te Rōpū Rangahau Hauora a Eru Pōmare, 3-10.

United Nations: United Nations Declaration on the rights of Indigenous peoples. Edited by: Nations U. 2008, Geneva: United Nations

Acosta D, Olsen P: Meeting the needs of regional minority groups: The University of Washington's programs to increase the American Indian and Alaskan native physician workforce. Academic Medicine. 2006, 81 (10): 863-870. 10.1097/01.ACM.0000238047.48977.05.

Farrington S, Page S, DiGregorio KD: The things that matter: Understanding the factors that affect the participation and retention of Indigenous students in the Cadigal Program at the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Sydney. Journal of Australia and New Zealand Student Services Association. 2001 (18): Paper presented at the Joint Annual Conference of the Australian Association for Research in Education (AARE) and New Zealand Association for Research in Education (NZARE), Melbourne

Hollow WB, Patterson DG, Olsen PM, Baldwin LM: American Indians and Alaska Natives: how do they find their path to medical school?. Academic Medicine. 2006, 81 (10 Suppl): S65-69.

Omeri A, Ahern M: Utilising culturally congruent strategies to enhance recruitment and retention of Australian indigenous nursing students. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 1999, 10 (2): 150-155. 10.1177/104365969901000209.

Usher K, Miller M, Turale S, Goold S: Meeting the challenges of recruitment and retention of Indigenous people into nursing: outcomes of the Indigenous Nurse Education Working Group. Collegian. 2005, 12 (3): 27-31. 10.1016/S1322-7696(08)60498-9.

Zuzelo PR: Affirming the disadvantaged student. Nurse Educator. 2005, 30 (1): 27-31. 10.1097/00006223-200501000-00008.

Thompson B, Miller L, thomson W, Dresden J: Evaluating magnet schools for the health professions: Career aspirations of Hispanic and non-minority students. The American Education Research Association Annual Meeting Atlanta. 1993

Kia Ora Hauora: Kia ora Hauora. 2011, Auckland: Counties Manukau District Health Board

Ratima M, Brown R, Garrett N, Wikaire E, Ngawati R, Aspin C, Potaka U: An Indigenous Medical Workforce. Stengthening Māori Participation in the New Zealand Health and Disability Workforce. Medical Journal of Australia. 2007, 186 (10): 541-543.

Andersen RM, Friedman J-A, Carreon DC, Bai J, Nakazono TT, Afifi A, Gutierrez JJ: Recruitment and retention of underrepresented minority and low-income dental students: effects of the Pipeline program. J Dent Educ. 2009, 73 (2 Suppl): S238-258. S375

The Sullivan Commission: Missing persons: Minorities in the health professions. A report of the Sullivan Commission on diversity in the healthcare workforce. 2004, The Sullivan Commission

Smith L: Decolonising Methodologies Research and Indigenous Peoples. 1999, Dunedin: University of Otago Press

Principles of Kaupapa Māori: [http://www.rangahau.co.nz/research-idea/27]

Valencia RR: The Evolution of Deficit Thinking: Educational Thought and Practice. 1997, Washington: The Palmer Press

Andersen RM, Carreon DC, Friedman J-A, Baumeister SE, Afifi AA, Nakazono TT, Davidson PL: What enhances underrepresented minority recruitment to dental schools?. J Dent Educ. 2007, 71 (8): 994-1008.

Anderson M, Lavallee B: The development of the First Nations, Inuit and Metis medical workforce. Medical Journal of Australia. 2007, 186 (10): 539-540.

Baker M: Developing the Maori nursing and midwifery workforce. Nursing New Zealand (Wellington). 2009, 15 (2): 28-

Bediako MR, McDermott BA, Bleich ME, Colliver JA: Ventures in education: A pipeline to medical education for minority and economically disadvantaged students. Academic Medicine. 1996, 71 (2): 190-192. 10.1097/00001888-199602000-00029.

Chesters J, Drysdale M, Ellender I, Faulkner S, Turnbull L, Kelly H, Robinson A, Chambers H: Footprints forwards blocked by a failure discourse: issues in providing advice about medicine and other health science careers to indigenous secondary school students.(Report). Australian Journal of Career Development. 2009, 18 (1): 26(10)

Collins JP, White GR, Mantell CD: Selection of medical students: an affirmative action programme. Medical Education. 1997, 31 (2): 77-80. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1997.tb02462.x.

Cooney R, Kosoko-Lasaki O, Slattery B, Wilson MR: Proximal versus distal influences on underrepresented minority students pursuing health professional careers. Journal of The National Medical Association. 2006, 98 (9): 1471-1475.

Cooper RA: Impact of trends in primary, secondary, and postsecondary education on applications to medical school. I: Gender considerations. Academic Medicine. 2003, 78 (9): 855-863. 10.1097/00001888-200309000-00003.

Fitzjohn J, Wilkinson T, Gill D, Mulder R: The demographic characteristics of New Zealand medical students: the New Zealand Wellbeing, Intentions, Debt and Experiences (WIDE) Survey of Medical Students 2001 study. The New Zealand medical journal. 2003, 116 (1183): U626-

Friedland ML, Kosko K, Lynch GA: An early-acceptance program for underrepresented minority or economically disadvantaged students. Academic medicine: journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 1997, 72 (5): 413-414. 10.1097/00001888-199705000-00034.

Gravely T, McCann A, Brooks E, Harman W, Schneiderman E: Enrichment and recruitment programs at dental schools: impact on enrollment of underrepresented minority students. J Dent Educ. 2004, 68 (5): 542-552.

Greenhalgh T, Russell J, Dunkley L, Boynton P, Lefford F, Chopra N: "We were treated like adults" - development of a pre-medicine summer school for 16 year olds from deprived socioeconomic backgrounds: action research study. Brit Med J. 2006, 332 (7544): 762-766B. 10.1136/bmj.38755.582500.55.

Greenhalgh T, Seyan K, Boynton P: "Not a university type" focus group study of social class, ethnic, and sex differences in school pupils' perceptions about medical school. BMJ. 2004, 328 (7455): 1541-10.1136/bmj.328.7455.1541.

Hollow W, Buckley A, Patterson DG, Olsen P, Medora R, Morin L, Padilla R, Tahsequah J, Baldwin L-M: Clearing the Path to Medical School for American Indians and Alaska Natives: New Strategies. 2006, Washington: School of Medicine, University of Washington and WWAMI Centre for Health Workforce Studies

Kivell D: Boosting Maori and Pacific nursing members. Interview by Teresa O'Connor. Nurs N Z. 2008, 14 (12): 20-21.

Kosoko-Lasaki O, Cooney R, Slattery B, Wilson MR: Proximal versus distal influences on underrepresented minority students pursuing health professional careers. Journal of The National Medical Association. 2006, 98 (9): 1471-1475.

Lawson KA, Armstrong RM, Van Der Weyden MB: Training Indigenous doctors for Australia: shooting for goal. Med J Aust. 2007, 186 (10): 547-550.

Lewis CL: A state university's model program to increase the number of its disadvantaged students who matriculate into health professions schools. Academic medicine: journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 1996, 71 (10): 1050-1057. 10.1097/00001888-199610000-00010.

Lopez N, Wadenya R, Berthold P: Effective recruitment and retention strategies for underrepresented minority students: perspectives from dental students. J Dent Educ. 2003, 67 (10): 1107-1112.

Participation analysis: All science subjects, Year 11 to 13 candidates: [http://www.maorihealth.govt.nz/moh.nsf/indexma/science-nationalparticipation]

Nikora LW, Levy M, Henry J, Whangapiritia L: An evaluation of Te Rau Puawai workforce 100: Evaluation overview (prepared for the Ministry of Health Technical report no. 1). 2002, Hamilton, New Zealand Māori and Psychology Research Unit, University of Waikato

Patterson DG, Hollow WB, Olsen PM, Baldwin LM: American Indians and Alaska natives: How do they find their path to medical school?. Academic Medicine. 2006, 81 (10): S65-S69.

Poole PJ, Moriarty HJ, Wearn AM, Wilkinson TJ, Weller JM: Medical student selection in New Zealand: looking to the future.[Erratum appears in N Z Med J. 2010;123(1308):following 123]. New Zealand Medical Journal. 2009, 122 (1306): 88-100.

Price SS, Crout RJ, Mitchell DA, Brunson WD, Wearden S: Increasing minority enrollment utilizing dental admissions workshop strategies. J Dent Educ. 2008, 72 (11): 1268-1276.

Royal Society of New Zealand: "Promoting Māori and Pasifika into health. science and technology: A report on the 4th March 2005 Symposium convened by Science and Technology Education Committee of the Royal Society of New Zealand and Māori Health and Disability Workforce Sub-Committee of the Health Workforce Advisory Committee". 2005, Wellington: Royal Society of New Zealand

Rumala BB, Cason FD: Recruitment of underrepresented minority students to medical school: minority medical student organizations, an untapped resource. Journal of The National Medical Association. 2007, 99 (9): 1000-1004. 1008-1009

Sewell J, Hawley N, Kingsley K, O'Malley S, Ancajas CC: Recent admissions trends at UNLV-SDM: perspectives on recruitment of female and minority students at a new dental school. J Dent Educ. 2008, 72 (11): 1261-1267.

Shields LA: El Paso Community College Health Careers Opportunity Program (HCOP). 1991, Texas: El Paso Community College, Texas

Unequal Treatment. Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare. Edited by: Smedley B, Stith A, Nelson A. 2002, Washington: Institute of Medicine of the National Academies Press

Soto-Greene M, Wright L, Gona OD, Feldman LA: Minority enrichment programs at the New Jersey Medical School: 26 years in review. Academic medicine: journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 1999, 74 (4): 386-389. 10.1097/00001888-199904000-00032.

Spencer A, Young T, Williams S, Yan D, Horsfall S: Survey on Aboriginal issues within Canadian medical programmes. Medical Education. 2005, 39 (11): 1101-1109. 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02316.x.

Stewart FM, Drummond JR, Carson L, Hoad Reddick G: The future of the profession-a survey of dental school applicants. Br Dent J. 2004, 197 (9): 569-573. 10.1038/sj.bdj.4811810. quiz 577

The Werry Centre for Child and Adolescent Mental Health: Targeted recruitment strategies: For the child and adolescent mental health and accictions workforce, with a Māori and Pacific focus. 2008, The Werry Centre for Child and Adolescent Mental Health

Thompson HC, Weiser MA: Support programs for minority students at Ohio University College of Osteopathic Medicine. Academic medicine: journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 1999, 74 (4): 390-392. 10.1097/00001888-199904000-00033.

University of Auckland: Māori and Pacific Success. Vision 20:20: Health Career Pathways. 2009, Auckland: University of Auckland, 1-14.

Usher K, Lindsay D, Mackay W: An innovative nurse education program in the Torres Strait Islands. Nurse Educ Today. 2005, 25 (6): 437-441. 10.1016/j.nedt.2005.04.003.

Wadenya RO, Lopez N: Parental involvement in recruitment of underrepresented minority students. J Dent Educ. 2008, 72 (6): 680-687.

Waetford C: New traditions: Best practice for promoting Māori secondary school students into health careers (Unpublished report). 2007, Auckland: Auckland District Health Board

Winkleby MA: The Stanford Medical Youth Science Program: 18 years of a biomedical program for low-income high school students. Academic Medicine. 2007, 82 (2): 139-145. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31802d8de6.

Beacham T, Askew RW, William PR: Strategies to increase racial/ethnic student participation in the nursing profession. Abnf J. 2009, 20 (3): 69-72.

Brunson WD, Jackson DL, Sinkford JC, Valachovic RW: Components of effective outreach and recruitment programs for underrepresented minority and low-income dental students. J Dent Educ. 2010, 74 (10 Suppl): S74-86.

Campbell-Heider N, Sackett K, Whistler MP: Connecting with guidance counselors to enhance recruitment into nursing of minority teens. J Prof Nurs. 2008, 24 (6): 378-384. 10.1016/j.profnurs.2008.10.009.

DeLapp T, Hautman MA, Anderson MS: Recruitment and retention of Alaska natives into nursing (RRANN). J Nurs Educ. 2008, 47 (7): 293-297. 10.3928/01484834-20080701-06.

Drysdale M, Faulkner S, Chesters J: Footprints forwards: Better strategies for the recruitment, retention and support of Indigenous medical students. 2006, Monash University School of Rural Health, Moe

Erwin K, Blumenthal DS, Chapel T, Allwood LV: Building an academic-community partnership for increasing representation of minorities in the health professions. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2004, 15 (4): 589-602. 10.1353/hpu.2004.0059.

Fields R, Moody NB: A view through a different lens ... strategies for increasing the number of African American nurses. Tenn Nurse. 2001, 64 (3): 10-13.

Fletcher A, Williams PR, Beacham T, Elliott RW, Northington L, Calvin R, Hill M, Haynes A, Winters K, Davis S: Recruitment, retention and matriculation of ethnic minority nursing students: a University of Mississippi School of Nursing approach. J Cult Divers. 2003, 10 (4): 128-133.

Gabard DL: Increasing minority representation in the health care professions. J Allied Health. 2007, 36 (3): 165-175.

Gordon FC, Copes MA: The Coppin Academy for Pre-Nursing Success: a model for the recruitment and retention of minority students. Abnf J. 2010, 21 (1): 11-13.

Haskins AR, Kirk-Sanchez N: Recruitment and retention of students from minority groups. Phys Ther. 2006, 86 (1): 19-29.

Indigenous Nursing Education Working Group (INEWG): 'gettin em n keepin em'. 2002, Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing, Office for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health

McClintock KK: Te Rau Piaatata: Mental health careers recruitment and promotion. 2008, Palmerston North, New Zealand: Te Rau Matatini

National Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander Health Council: A blueprint for action: Pathways into the health workforce for Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander people. 2008, Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia

Nnedu CC: Recruiting and retaining minorities in nursing education. Abnf J. 2009, 20 (4): 93-96.

Noone J: The diversity imperative: strategies to address a diverse nursing workforce. Nurs Forum. 2008, 43 (3): 133-143. 10.1111/j.1744-6198.2008.00105.x.

Noone J, Carmichael J, Carmichael RW, Chiba SN: An organized pre-entry pathway to prepare a diverse nursing workforce. J Nurs Educ. 2007, 46 (6): 287-291.

Phillips JL, Wile MZ: Academic outreach: health careers enhancement program for minorities. Journal of The National Medical Association. 1990, 82 (12): 841-846.

Turale S, Miller M: Improving the health of Indigenous Australians reforms in nursing education An opinion piece of international interest. Int Nurs Rev. 2006, 53 (3): 171-177. 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2006.00476.x.

Waetford C: Rangatahi programme health workforce development pilot project report 2007. 2007, Auckland: Auckland District Health Board

Wiggs JS, Elam CL: Recruitment and retention: the development of an action plan for African-American health professions students. Journal of The National Medical Association. 2000, 92 (3): 125-130.

Participation analysis: All science subjects, Year 11 to 13 candidates. [http://www.maorihealth.govt.nz/moh.nsf/indexma/science-nationalparticipation]

Participation and Attainment of Māori students in National Certificate of Aducation Achievement. [http://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/statistics/pasifika_education/schooling/participation-and-attainment-of-maori-students-in-national-certificate-of-educational-achievement]

Participation and Attainment of Pasifika students in National Certificate of Educational Achievement. [http://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/statistics/pasifika_education/schooling/participation-and-attainment-of-pasifika-students-in-national-certificate-of-educational-achievement]

Kelly H, Robinson A, Drysdale M, Chesters J, Faulkner S, Ellender I, Turnbull L: "It's not about me, it's about the community": Culturally relevant health career promotion for Indigenous students in Australia. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education. 2009, 38: 19-26.

D'Antoine N, Paul D: Creating opportunities for Indigenous Students. Aboriginal and Islander Health Worker Journal. 2006, 30 (3): 6-8.

Madjar I, McKinley E, Deynzer M, van der Merwe A: Stumbling blocks or stepping stones? Students' experience of transition from low-mid decile schools to university. 2010, Auckland: Starpath Project, The University of Auckland

Garvey G, Rolfe IE, Pearson S-A, Treloar C: Indigenous Australian medical students' perceptions of their medical school training. Medical Education. 2009, 43 (11): 1047-1055. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03519.x.

Australian Indigenous Doctors' Association: Improving the transition into health careers for Aborinigal and Torres Strait Islander school students. 2010, Australia: Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations

Hefford M, Crampton P, Foley J: Reducing health disparities through primary care reform: The New Zealand experiment. Health Policy. 2005, 72 (1): 9-23. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.06.005.

Tertiary Education Commission: Tertiary education strategy 2010-2015: Part Two - Priorities. 2011, Wellington: Ministry of Education

Ministry of Education: New Zealand's tertiary education sector report - profile & trends 2002. 2003, Wellington: Ministry of Education

Ministry of Education: Tertiary education strategy 2010-15. 2009, Wellington: Ministry of Education

The University of Auckland Kia Ora Hauora: Eke Panuku! Eke Tangaroa! Māori Student Success in Health Careers Symposium: Recruitment Workshop. Eke Panuku! Eke Tangaroa! Māori Student Success in Health Careers Symposium: 2011; Auckland. 2011

Mackean T, Mokak R, Carmichael A, Phillips GL, Prideaux D, Walters TR: Reform in Australian medical schools: a collaborative approach to realising Indigenous health potential. Med J Aust. 2007, 186 (10): 544-546.

Jacobi M: Mentoring and Undergraduate Academic Success: A literature Review. Review of Educational Research. 1991, 61 (4): 505-532.

Tertiary Education Strategy 2010-2015. [http://www.minedu.govt.nz/NZEducation/EducationPolicies/TertiaryEducation/PolicyAndStrategy/TertiaryEducationStrategy.aspx]

Ministry of Health: Raranga Tupuake: Māori health workforce development plan 2006. 2006, Wellington: Ministry of Health

Acknowledgements

Dr Elana Curtis was supported by Te Kete Hauora, Ministry of Health to complete the drafting of this manuscript via the provision of a Research Fellowship (Contract 414953/337535/00).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

EC developed and led the concept development and study design, carried out the literature review and analysis and drafted the manuscript. EW completed the literature content analysis, and contributed to the literature search, drafting and revising the manuscript. KS completed the literature search and initial inclusion/exclusion of articles, participated in the study design and analysis and contributed to drafting and revising the manuscript. Associate Professor Papaarangi Reid participated in the study design and methodological approach. PR also contributed to the drafting and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Curtis, E., Wikaire, E., Stokes, K. et al. Addressing indigenous health workforce inequities: A literature review exploring 'best' practice for recruitment into tertiary health programmes. Int J Equity Health 11, 13 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-11-13

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-11-13