Abstract

Background

The study of body composition in specific populations by techniques such as bio-impedance analysis (BIA) requires validation based on standard reference methods. The aim of this study was to develop and cross-validate a predictive equation for bioelectrical impedance using air displacement plethysmography (ADP) as standard method to measure body composition in Mexican adult men and women.

Methods

This study included 155 male and female subjects from northern Mexico, 20–50 years of age, from low, middle, and upper income levels. Body composition was measured by ADP. Body weight (BW, kg) and height (Ht, cm) were obtained by standard anthropometric techniques. Resistance, R (ohms) and reactance, Xc (ohms) were also measured. A random-split method was used to obtain two samples: one was used to derive the equation by the "all possible regressions" procedure and was cross-validated in the other sample to test predicted versus measured values of fat-free mass (FFM).

Results and Discussion

The final model was: FFM (kg) = 0.7374 * (Ht2 /R) + 0.1763 * (BW) - 0.1773 * (Age) + 0.1198 * (Xc) - 2.4658. R2 was 0.97; the square root of the mean square error (SRMSE) was 1.99 kg, and the pure error (PE) was 2.96. There was no difference between FFM predicted by the new equation (48.57 ± 10.9 kg) and that measured by ADP (48.43 ± 11.3 kg). The new equation did not differ from the line of identity, had a high R2 and a low SRMSE, and showed no significant bias (0.87 ± 2.84 kg).

Conclusion

The new bioelectrical impedance equation based on the two-compartment model (2C) was accurate, precise, and free of bias. This equation can be used to assess body composition and nutritional status in populations similar in anthropometric and physical characteristics to this sample.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The importance of measuring body composition has increased, due to the need to evaluate changes in nutritional status, which can affect body reserves differentially. Subjects can gain or lose body fat, fat-free mass, bone mineral mass or cellular mass components as a result of disease, overeating, sports, or undernutrition (anorexia nervosa), or as a result of nutritional intervention programs. These changes can only be detected by using valid body composition measurement techniques. In addition, the world-wide epidemic of obesity and its association with chronic disease has also contributed to the need to study body composition [1, 2]and the distribution of body components [3]. The definition of obesity based on body size has been challenged in regard to different populations, due to the different relationships of percent body fat at the same BMI levels [4]. Therefore, a definition of obesity based on body composition terms can help to clarify this issue.

In order to have good body composition estimates from bioelectrical impedance techniques, it is necessary to have proper validation based on reference methods of better accuracy and precision. Recently, it has been reported that air displacement plethysmography (ADP) is a valid method to determine body composition compared with hydrodensitometry and the four compartment model in adults [5, 6]. However, these standard reference methods are difficult to implement in some clinical settings and in epidemiological studies.

It is well recognized that the BIA technique when properly validated is a practical option for these types of studies. Body composition assessment by bioelectrical impedance can be improved when the specific equations used are validated against reference methods and for a specific population [7, 8]. Furthermore, validated BIA equations can overcome some limitations due to differences in fat distribution patterns and limb length (arm and leg) [9] between ethnic groups that might affect the accuracy and precision of the technique [10]. Finally, it is important to mention that most published BIA equations derive from Caucasian populations, and presently there are no published equations for Mexican adults. The aim of this study was to develop and cross-validate a predictive equation for bioelectrical impedance using air displacement plethysmography (ADP) as a standard method to measure body composition in Mexican adult men and women.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study in healthy men and women, 20 to 50 years of age, residing in Sonora, Mexico. Participants were selected by nonprobabilistic sampling between 2000 and 2001. Pregnant and lactating women and subjects with diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or any other condition that could cause hydro-electrolytic imbalance were excluded. In addition, none of the participants were on diuretics or other medication that could alter body composition. The Ethics Committee of the Centro de Investigacion en Alimentacion y Desarrollo (CIAD: Food and Development Research Center) approved the study.

All body composition measurements were performed in CIAD's metabolic unit. Prior to the measurements, all participants signed a written consent form after being informed of procedures and purpose of the study. Subjects were asked to fast for 12 h, to not perform exercise the day before the measurements, and to empty their bladder prior to evaluation.

Human body volume, body density, and body composition were evaluated with ADP (Bod Pod, Body Composition System, Life Measurement Instruments, Concord, CA). The system determines body volume by the application of Boyle's gas law. The ADP unit consists of a dual-chamber plethysmograph, an electronic scale, and a computer. This equipment has a single structure containing two chambers separated by a device that produces pressure fluctuations and volume changes that permit the assessment of body volume. The system has been described in detail elsewhere [11]. Wearing a swimsuit and acrylic swimming cap, subjects were first weighed to the nearest 0.01 kg with the ADP electronic scale. A two-point calibration was performed, with the chamber empty and with a 50 L cylinder. After the calibration procedure, the subject's body volume was measured twice while they were seated quietly in the test chamber and breathing normally. In the second trial, thoracic gas volume was measured to correct the body volume. From the corrected body volume and body mass values, body density was obtained and percent body fat was calculated using Siri's equation and ADP software. Fat-free mass was calculated from the two-compartment model [12]. All measurements were done following the manufacturer's instructions.

The reproducibility of air displacement plethysmography system was tested using duplicate measurements in 91 subjects. The duplicate measurements were both performed during the same session. The duplicated mean body density measurements were 1.0292 ± 0.019 and 1.0296 ± 0.019, and the mean difference in body density was 0.00007. The coefficient of variation for both measurements was 1.89%. In terms of %BF, the technical error of measurement was 0.066 % fat units, assessed as (Σd2/2n)1/2, where d is the difference between repeated measurements and n is the number of paired repeated measurements.

Anthropometry was performed by a standardized technician according to Lohman's recommendations [13]. Body weight (BW) was measured in subjects dressed in a swimsuit using a digital electronic scale (150 ± 0.01 kg) connected to the ADP. Standing height was measured with a Holtain stadiometer to the nearest millimeter (205 ± 0.5 cm, Holtain Limited, Dyfed, UK). Body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) was calculated based on weight and standing height. Waist circumference was measured in supine position at the umbilicus level, and hip circumference was evaluated in standing position at the level of the most prominent part of the gluteus. Both measurements were done with a fiberglass measuring tape (Lafayette Instruments Company Inc., USA). Waist/hip ratio (WHR) was determined from these measurements.

Resistance (R) and reactance (Xc) were measured with a bioelectrical impedance analyzer (Model BIA-103, RJL Systems Detroit, MI) according to the manufacturer's instructions. BIA equipment calibration was periodically performed with an electrical resistor. Calibration values were considered normal if they were not higher than 498 ± 2 ohms (Ω). Volunteers were instructed to lie supine with their hands at their side and with their legs separated. The skin surface was cleaned with ethanol, and the electrodes were placed on the dorsum of the right foot and hand. All measurements were performed according to Lukasky [14].

Data were analyzed using the statistical program, NCSS 2001 (Number Cruncher Statistical System for Windows, Kaysville, Utah). The t-test for independent samples was used to evaluate differences of general characteristics between men and women and also between samples. All results are expressed as means ± standard deviations (SD).

For the design of the BIA equation, the total sample (n = 155) was used in a split-sample internal cross-validation. In this approach, the sample was split randomly into subsamples of approximately the same size (78 and 77 subjects each) (Table 2). The regression equation was developed in a randomized sample of 78 subjects. This equation had the lowest SEE and highest R2, and was cross-validated using the second sample of 77 subjects. Model selection was carried out using the "all possible regressions" procedure. This method guarantees finding the model having the largest R2 and the smallest square root of MSE (SRMSE). Mallow's Cp statistic was used to optimize model selection. Multiple regression procedure was used to analyze the relation between FFM as a dependent variable with: age (years), sex (male = 1, female = 0), body weight (kg), square height (cm)/resistance (Ω) (Ht2/R), and reactance (Ω) as independent variables. Multicolinearity was analyzed by regression diagnostics using the condition number (CN < 30) and the variance inflation factor (VIF < 10). The pure error was calculated as the square root of the sum of squared differences between the observed and the predicted values divided by the number of subjects in the cross-validation sample [15].

Validation of the new BIA equation was done using the split-sample internal cross-validation method. Body composition was estimated in the second randomized group or validation sample (77 subjects) using the new equation developed from the first randomized group, or equation sample (78 subjects). Estimates of body composition, particularly the FFM predicted by the new BIA equation, were compared to values measured by ADP (the reference method) using a paired t-test. The accuracy and precision of the new BIA equation were tested by regression procedures. It was considered accurate if the regression between fat-free mass by ADP and the new BIA equation had a slope not significantly different from 1.0 and an intercept not significantly different from zero. Precision was assessed by the model R2 and the standard error of the estimate from the regression procedures described above. Bias was examined using Bland and Altman's analysis [16] and regression procedures.

Results

In this study, 155 healthy adults (82 women and 73 men) were evaluated. General characteristics of the subjects are presented in Table 1. As expected, the men had significantly higher values of weight, height, waist, and waist/hip ratio compared with the women.

Table 2 shows the main variables in the randomly split samples. There were no significant differences between the values from the randomized sample used for developing the equation and the randomized sample for testing it. The equation obtained was:

FFM (kg) = 0.7374 * (Ht2/R) + 0.1763 * (BW)- 0.1773 * (Age) + 0.1198 * (Xc)- 2.4658

Where: Ht2 is height in cm, R is resistance in ohms, BW is body weight in kg, age is in years, and Xc is reactance in ohms

The independent variables that most accurately estimated fat-free mass were Ht2/R, BW, Xc, and age (Table 3). By partial R2 analysis, Ht2/R and body weight were the best individual predictors of FFM (kg), and accounted for 91.5% and 72.7% respectively, whereas reactance accounted for 2.56% and age for only 0.38% (Table 3). The final model included all these variables, with an F value of 568, R2 of 0.97, an SRMSE of 1.99 kg, and a pure error (PE) of 2.96. Sex was not selected in this model as an independent variable. No multicolinearity was detected according to the regression diagnostic; the variance inflation factor (VIF) was 7.7 and the condition number (CN) was 9.82.

The use of the paired t-test showed that there was no significant difference between the FFM measured with ADP and that estimated with the new BIA equation validated in the present study (Table 4) (p < 0.05). Furthermore, the percent-body-fat values obtained with the two compartment model from the new, validated BIA equation did not differ from the percent-body-fat values measured by ADP.

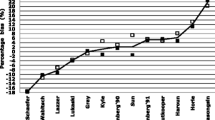

The mean values of FFM predicted by the new BIA equation and measured by ADP in the validation sample were 48.57 ± 10.9 kg and 48.43 ± 11.3 kg, respectively. There was no significant difference from the line of identity: the intercept was 0.02 and not different from zero, and the slope was 0.98 and not different from 1.0. The R2 was 0.92 and the SRMSE was 2.86 (Figure 1). Bland and Altman analysis revealed that the bias expressed as the mean of the difference in FFM measured by ADP and that estimated from the new BIA equation was -0.87 ± 2.84 kg of FFM. The limits of agreement, defined as mean ± 2 SDs, were from -6.56 to + 4.82 kg of FFM (Figure 2). Furthermore, there was no significant association (p > 0.05) between the mean differences and the mean of two measurements (FFM obtained by ADP and the new validated equation (Figure 2).

Discussion

The equation developed in the present study is the first validated BIA equation for Mexican adults, to the authors' knowledge. We found the new equation to be accurate, precise, and free of bias. FFM, and therefore FM, values obtained with equations developed for specific populations are more accurate and precise [8], as seen in the present study. The equation developed in this study takes into account the physical and body composition characteristics of the group used to design the equation, making it more population/environment specific.

Ethnicity has been shown to be an important factor when looking at the relationships of percent body fat and BMI. Among Chinese, Malay and Indian subjects, the Chinese showed the lowest body-fat value and Indians the highest at the same BMI level [17]. In our study, the BF% by the reference method was 25.9 in men and 36.2 in women at BMI values of 25.4 and 26.2, respectively. The percent body fat for the Mexican subjects of this study seems to be more similar to that of the Asian population reported by Gallagher [4] than to that obtained from Caucasians and Afro-Americans, who have less body fat at the same BMI. In addition to the differences in BMI, other researchers have reported fat distribution discrepancies between ethnic groups that could diminish the accuracy of body composition values obtained with BIA and anthropometric equations [18–21].

Casas et al. [21], evaluated 54 Hispanic women and 56 white women to determine whether Hispanic ethnicity is associated with total and regional adiposity and low FFM in healthy women. They found that Hispanic women have higher adiposity levels than white women. This difference reflected a higher amount of fat in the trunk. Further, abdominal and subscapular thicknesses were greater in Hispanic than in white women. These findings support the need to develop validated BIA and anthropometric equations for Hispanics. The best BIA equations developed for specific population groups have been properly validated [22–24].

The body composition variables selected in the final model of this study have been reported as the best predictors in BIA equations designed to estimate FFM [25–27]. The BIA equation developed in this study (R2 = 0.97; SRMSE= 1.99) was similar to or better than those obtained with other equations designed with comparable sample sizes, such as that of Lukasky (84 males; 67 females) [27] based on hydrodensitometry (R2 = 0.96; SEE = 3.06), or of Baumgartner (35 males; 63 females)[28] based on a four compartment model (R2 = 0.91; SEE = 2.47).

There were no differences between the mean predicted FFM and measured values by ADP. The pure error was small and comparable to good cross-validated equations reported in the literature [15]. There is no criterion value for the pure error that indicates successful cross-validation. However, the pure error should be similar to the precision (square root of the MSE value, SRMSE) of the validated equation in the population from where it is derived. Here the pure error is slightly higher than the SRMSE, indicating that the cross-validation was successful.

The new equation showed good precision. Similar findings were reported by Rising et al. [8]; the specific BIA equation developed (using hydrostatic weighing) for Pima Indians improved the average accuracy to -0.1 ± 3.3 kg versus the manufacturer's equation, which underestimated the fat-free mass by 5.3 ± 8.6 kg. Other studies have shown poor validity when equations designed and validated in one population have been used to predict FFM in other populations [29].

One of the most important justifications for designing and validating BIA estimation equations for specific groups is their differences in limb length [30]. The explanation for this could be that limb length and body weight are positively related to resistance, which is the main predictor of FFM estimated with BIA [27]. Limb length and body weight are strongly related to ethnicity and environmental factors. Deurenberg et al. demonstrated that limb length, expressed as leg length/height, influences the body composition values obtained with BIA; the length of the limbs was different among Chinese, Malays, and Indians. The authors consider the bias between TBW obtained with the deuterium dilution method and BIA values to be due to ethnic differences [30].

The regression analysis between FFM values estimated with the BIA equation validated in the present study and ADP (Figure 1) showed that the BIA equation was accurate and precise. Furthermore, Bland and Altman analysis determined there was no significant bias for FFM values obtained with the validated equation (Figure 2). These results are those expected for an equation that is population specific.

A recent and thorough review in the assessment of body composition using ADP[6] analyzed the validity of ADP relative to hydrostatic weighing (HW) in male and female adults, age 20–56 years. Mean group differences between ADP and HW measurements ranged from -4% to 1.9 % body fat; 5 of the 12 studies showed no significant difference between the two methods. Of the other 7 studies that did show a significant mean difference, the direction of the differences was inconsistent. Percent fat measured by ADP explained 78–94 % of the variance in % body fat measured by HW and the reported SEEs ranged from 1.8 to 2.3 % and ideally the range should be < 2.5 % body fat. These authors state that, whether the sex of the subject systematically affects results from ADP or HW remains to be determined. Because males tend to be leaner than females, it is difficult to determine whether the significant effect of sex reported in some studies are due to an effect of sex per se or to body fatness. Plotting the results from different studies as sex-specific means, in Bland-Altman fashion, they observed an upward trend with no overlap in mean % body fat between females and males. Therefore they conclude that in their analysis as in the individual studies, it is impossible to separate the confounding effects of subject sex and % body fat. Even though many studies consider ADP as a reliable and valid technique applicable in a wide range of subjects including children and elderly, more validation studies are required using a 4 Compartment model as a reference gold standard rather than HW. Other studies [31] suggest that that it is important to test its accuracy in more heterogeneous samples, or in individuals outside the average % fat range, specifically lean individuals, and insist in looking at possible gender bias. In our laboratory we have previously validated ADP using a 4 Compartment model in elderly subjects [32] as well as in children and adolescents (studies in progress).

Conclusion

The new bioelectrical impedance equation based on a two-component model method was accurate, precise, and free of bias. The prediction validated equation can be used to assess body composition and nutritional status in populations having anthropometric and physical characteristics similar to this sample. However, we acknowledge the fact that there might be a problem of generality because it does not include Mexicans from all the country. Ethnic and environmental differences are the main factors that could affect the general applicability of the equation, and it should be used with caution.

References

Siervogel RM, Wisemandle W, Maynard LM, Guo SS, Roche AF, Chumlea WC, Towne B: Serial changes in body composition throughout adulthood and their relationships to changes in lipid and lipoprotein levels. The Fels Longitudinal Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998, 18 (11): 1759-1764.

Couillard C, Lemieux S, Moorjani S, Lupien PJ, Theriault G, Prud'homme D, Tremblay A, Bouchard C, Despres JP: Associations between 12 year changes in body fatness and lipoprotein-lipid levels in men and women of the Quebec Family Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1996, 20 (12): 1081-1088.

Spiegelman D, Israel RG, Bouchard C, Willett WC: Absolute fat mass, percent body fat, and body-fat distribution: which is the real determinant of blood pressure and serum glucose?. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992, 55 (6): 1033-1044.

Gallagher D, Heymsfield SB, Heo M, Jebb SA, Murgatroyd PR, Sakamoto Y: Healthy percentage body fat ranges: an approach for developing guidelines based on body mass index. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000, 72 (3): 694-701.

Demerath EW, Guo SS, Chumlea WC, Towne B, Roche AF, Siervogel RM: Comparison of percent body fat estimates using air displacement plethysmography and hydrodensitometry in adults and children. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002, 26 (3): 389-397. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801898.

Fields DA, Goran MI, McCrory MA: Body-composition assessment via air-displacement plethysmography in adults and children: a review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002, 75 (3): 453-467.

Jakicic JM, Wing RR, Lang W: Bioelectrical impedance analysis to assess body composition in obese adult women: the effect of ethnicity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998, 22 (3): 243-249. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800576.

Rising R, Swinburn B, Larson K, Ravussin E: Body composition in Pima Indians: validation of bioelectrical resistance. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991, 53 (3): 594-598.

Okosun IS, Tedders SH, Choi S, Dever GE: Abdominal adiposity values associated with established body mass indexes in white, black and hispanic Americans. A study from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000, 24 (10): 1279-1285. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801414.

Fuller NJ, Elia M: Potential use of bioelectrical impedance of the 'whole body' and of body segments for the assessment of body composition: comparison with densitometry and anthropometry. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1989, 43 (11): 779-791.

Dempster P, Aitkens S: A new air displacement method for the determination of human body composition. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995, 27 (12): 1692-1697.

Siri WE: Body composition from fluid spaces and density: analysis of methods. Techniques for measuring body composition. Edited by: Brozek J, Henschel A. 1961, Washigton DC , National Academy of Sciences/National Research Council, 223-234.

Lohman TG, Roche AF, R M: Anthropometric standardization reference manual. 1988, Champaign, IL , Human Kinetics , 177-

Lukaski HC, Johnson PE, Bolonchuk WW, Lykken GI: Assessment of fat-free mass using bioelectrical impedance measurements of the human body. Am J Clin Nutr. 1985, 41 (4): 810-817.

Sun SS, Chumlea WC, Heymsfield SB, Lukaski HC, Schoeller D, Friedl K, Kuczmarski RJ, Flegal KM, Johnson CL, Hubbard VS: Development of bioelectrical impedance analysis prediction equations for body composition with the use of a multicomponent model for use in epidemiologic surveys. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003, 77 (2): 331-340.

Bland JM, Altman DG: Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986, 1 (8476): 307-310.

Deurenberg-Yap M, Schmidt G, van Staveren WA, Deurenberg P: The paradox of low body mass index and high body fat percentage among Chinese, Malays and Indians in Singapore. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000, 24 (8): 1011-1017. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801353.

Immink MD, Flores R, Diaz EO: Body mass index, body composition and the chronic energy deficiency classification of rural adult populations in Guatemala. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1992, 46 (6): 419-427.

Ramirez-Zea M, Torun B, Martorell R, Stein AD: Anthropometric predictors of body fat as measured by hydrostatic weighing in Guatemalan adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006, 83 (4): 795-802.

Fernandez JR, Heo M, Heymsfield SB, Pierson RN, Pi-Sunyer FX, Wang ZM, Wang J, Hayes M, Allison DB, Gallagher D: Is percentage body fat differentially related to body mass index in Hispanic Americans, African Americans, and European Americans?. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003, 77 (1): 71-75.

Casas YG, Schiller BC, DeSouza CA, Seals DR: Total and regional body composition across age in healthy Hispanic and white women of similar socioeconomic status. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001, 73 (1): 13-18.

Masuda T, Komiya S: A prediction equation for total body water from bioelectrical impedance in Japanese children. J Physiol Anthropol Appl Human Sci. 2004, 23 (2): 35-39. 10.2114/jpa.23.35.

Kyle UG, Genton L, Karsegard L, Slosman DO, Pichard C: Single prediction equation for bioelectrical impedance analysis in adults aged 20--94 years. Nutrition. 2001, 17 (3): 248-253. 10.1016/S0899-9007(00)00553-0.

Valencia ME, Aleman-Mateo H, Salazar G, Hernandez Triana M: Body composition by hydrometry (deuterium oxide dilution) and bioelectrical impedance in subjects aged >60 y from rural regions of Cuba, Chile and Mexico. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003, 27 (7): 848-855. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802315.

Guo SS, Chumlea WC, Cockram DB: Use of statistical methods to estimate body composition. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996, 64 (3 Suppl): 428S-435S.

Baumgartner RN, Heymsfield SB, Lichtman S, Wang J, Pierson RN: Body composition in elderly people: effect of criterion estimates on predictive equations. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991, 53 (6): 1345-1353.

Lukaski HC, Bolonchuk WW, Hall CB, Siders WA: Validation of tetrapolar bioelectrical impedance method to assess human body composition. J Appl Physiol. 1986, 60 (4): 1327-1332.

Baumgartner RN, Chumlea WC, Roche AF: Estimation of body composition from bioelectric impedance of body segments. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989, 50 (2): 221-226.

Dioum A, Gartner A, Cisse AS, Delpeuch F, Maire B, Wade S, Schutz Y: Validity of impedance-based equations for the prediction of total body water as measured by deuterium dilution in African women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005, 81 (3): 597-604.

Deurenberg P, Deurenberg-Yap M, Schouten FJ: Validity of total and segmental impedance measurements for prediction of body composition across ethnic population groups. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002, 56 (3): 214-220. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601303.

Vescovi JD, Zimmerman SL, Miller WC, Hildebrandt L, Hammer RL, Fernhall B: Evaluation of the BOD POD for estimating percentage body fat in a heterogeneous group of adult humans. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2001, 85 (3-4): 326-332. 10.1007/s004210100459.

Aleman-Mateo H, Huerta RH, Esparza-Romero J, Mendez RO, Urquidez R, Valencia ME: Body composition by the four-compartment model: validity of the BOD POD for assessing body fat in mexican elderly. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2007

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Macias, N., Alemán-Mateo, H., Esparza-Romero, J. et al. Body fat measurement by bioelectrical impedance and air displacement plethysmography: a cross-validation study to design bioelectrical impedance equations in Mexican adults. Nutr J 6, 18 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-6-18

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-6-18