Abstract

Background

Attrition is an important but understudied issue that plays a vital role in the successful treatment of obesity. To date, most studies focusing on attrition rates and/or its predictors have been based on pretreatment data routinely collected for other purposes. Our study specifically aims at identifying the predictors of drop-out focusing on empirically or theoretically-based factors.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective observational study in an academic outpatient clinical nutrition service in Pavia, Italy. We examined a total of 98 adult obese patients (36 males, 62 females) who underwent a 6-month dietary behavioral weight-loss treatment at our Center. Pre-treatment and treatment-related variables were collected or calculated from clinical charts in order to discriminate those subjects who completed treatment from those who abandoned it before its completion. Multivariable regression analysis was used to identify the independent predictors of drop-out.

Results

The drop-out rates were 21% at 1 month and 57% at 6 months. Compared with completers, noncompleters were significantly younger in terms of age at first dieting attempt (24.0 ± 10.7 vs. 31.3 ± 11.2 years, P = 0.005), had lower diastolic blood pressure (87.8 ± 9.7 vs. 92.7 ± 11.4 mmHg, P = 0.022), had a lower baseline body fat percentage (38.5 ± 6.4 vs. 41.2 ± 4.4% weight, P = 0.015), and had a lower percentage of early weight loss (-1.8 ± 1.8% vs. -3.1 ± 2.1%, P = 0.035). Moreover, noncompleters significantly differed from completers with regard to type of referral (34.1% vs. 53.3% sent by a physician, P = 0.036) and SCL-90 anger-hostility subscale (0.83 ± 0.72 vs. 0.53 ± 0.51, P = 0.022). A multivariable logistic regression analysis including pre-treatment variables showed that body fat percentage (P = 0.030) and SCL-90 anger-hostility subscale (P = 0.021) were independently associated with attrition. In a multivariable model considering both pre-treatment and treatment-related factors, attrition was found to be independently related to the age at first dieting attempt (P = 0.016) and the achievement of early weight loss (P = 0.029).

Conclusions

Our data confirm that psychopathological tracts, early dieting attempts, and a poor initial treatment response are key independent predictors of drop-out from obesity treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The treatment of obesity continues to present major challenges, including poor adherence to diet, inadequate and unsatisfactory weight loss, weight regain, and high rates of attrition. The literature on attrition in the treatment of obesity is heterogeneous, with ranges varying from 10% to 80% depending on the setting and the type of program [1]. Notably, intervention trials reported a mean attrition rate of more than 40% within the first 12 months [2].

To date, most studies focusing on attrition rates and/or its predictors have been based on pre-treatment data (e.g., weight and presence of comorbidities) routinely collected for other purposes (e.g., identifying predictors and correlates of weight loss) [3–8]. High drop-out rates from obesity treatment have been associated with baseline characteristics such as young age [3, 9–11], low education levels [6, 9, 12], poor dieting behaviors [3, 5, 8, 12, 13], and unhealthy lifestyles [12–15]. However, the literature on predictors of attrition in obesity treatment is limited by different study designs and inconsistencies across studies.

Emerging evidence suggests that psychological distress (including depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem) [4, 7, 9, 12, 16–19] and the failure to achieve reasonable weight loss goals during the first weeks of treatment [4–6, 9, 12, 13, 15] are important predictors of drop-out. Previous studies have also reported high rates of psychopathology both in obese [20–22] and normal-weight persons [23] wishing to lose weight. These findings suggest that factors related to the psychological well-being need to be carefully considered so that obese patients keep attending their weight loss program.

The present study specifically aims at identifying the predictors of drop-out from obesity treatment focusing on empirically (e.g., unsatisfactory early weight loss) or theoretically-based (e.g., psychopathological symptoms and dieting behaviors) factors. Because some results may be population-specific [24, 25], we also sought to replicate in an Italian academic setting the previously identified predictors of drop-out [1, 3–19].

Methods

Study design and sample

This research was designed as a retrospective observational study. Participants were adult (age ≥ 18 years) obese patients (body mass index [BMI] ≥ 30 kg/m2) who were consecutively referred for weight loss to the Human Nutrition Research Centre, University of Pavia (Italy) between January 2006 and December 2008. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, major physical illnesses, and psychiatric disorders requiring treatment with atypical antipsychotics. All of the participants underwent a standardized psychological and nutritional assessment before starting a dietary/behavioral weight loss protocol. This study was conducted according to the tenets of Helsinki Declaration and all procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pavia. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Weight loss protocol

The weight loss protocol consisted in a 6-month dietary behavioral program. A dietary plan was prepared by a registered dietician for every patient at the beginning of the program; the dietary plan consisted of an individualized balanced low-calorie diet. The energy content was calculated to obtain a weight loss of 0.5 to 1 kg/wk within 6 months according to the Clinical guidelines for the treatment of obesity [26]. The macronutrient composition targets were 25-30% for fats, 55-65% for carbohydrates and 15% for proteins according to the Dietary Reference Values [27]. The diets were calculated using Dieta Ragionata 7.0 (Esi Stampa Medica srl, San Donato Milanese, Italy) which includes the Italian food composition tables. The patients were required to visit our center on a monthly basis for follow-up visits, which were conducted by a physician specialized in clinical nutrition. During the visits, we checked patient body weight and body composition and, when necessary, delt with obstacles hindering weight loss and physical activity. Moreover, possible changes to the dietary plan were discussed with the dietician.

Predictors of drop-out

The potential predictors of drop-out were collected and/or calculated from clinical charts. Both pre-treatment (i.e., socio-demographic, nutritional, psychopathological features) and treatment-related variables (i.e., achievement of early weight loss at one month) were considered for the purpose of analysis. The following data were collected: socio-demographic characteristics (age, sex, marital status, education level, occupational status, smoking habits, physical activity), anthropometric and nutritional variables (weight, height, BMI, waist and hip circumference, waist-to-hip ratio [WHR]), baseline body composition (percentage body fat [%BF] from skinfold thickness), lower and higher weight achieved during adulthood, age at first dieting attempt, number and reasons of previous attempts to lose weight, type of referral, weight loss goals, and components of the metabolic syndrome. The psychopathological features were assessed by means of validated psychometric instruments. In all participants, we assessed weight loss goals and the achievement of early weight loss at 1 month.

Psychometric tests

The Symptoms Checklist-90-R (SCL-90-R), a self-report checklist inquiring about symptoms during the preceding week, was used as a measure of general psychopathology [28]. Depressive symptoms and eating behaviors were determined using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [29] and the Binge Eating Scale (BES) [30], respectively.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were expressed as percentages and compared using the chi-squared test or the Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Continuous data were summarized as means and standard deviations. Unpaired Student’s t-tests (with Satterthwaite’s correction for degrees of freedom) or the Mann-Whitney’s U tests were applied to assess the differences in quantitative variables between patients who dropped out at 1 and 6 months and treatment completers. The net changes in the study variables at 6 months were expressed as percentages of the baseline data and compared using paired Student’s t-tests. We used multivariable logistic regression analysis to identify the independent predictors of attrition. All of the variables which were significantly associated with attrition (P < 0.05) in univariate analyses were selected into the multivariable model. All calculations were performed using the statistical softwares Stata 10 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) and SPSS 14.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A two-tailed P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

General characteristics of completers and noncompleters

Ninety-eight obese adults (36 males and 62 females) were included in the study. The total drop-out rate at one month was 21 (21.4%), without significant sex differences (27.8% in males and 17.7% in females; χ2 = 1.4, P = 0.243). At 6 months, the total drop-out rate (including subjects who dropped-out at 1 month) was 57% (56 subjects). Again, we found no evidence of a significant sex difference (55.6% in males and 58.1% in females; χ2 = 0.1, P = 0.809). Table 1 shows the general characteristics of the entire study cohort, divided in completers and noncompleters. Subjects who did not complete the weight loss program were significantly younger at their first dieting attempt; moreover, they had lower%BF (skinfold thickness) and diastolic blood pressure values compared with completers. No other significant intergroup differences were noted in terms of clinical, nutritional, socio-demographic, and lifestyle-related characteristics.

Of the 42 subjects who completed treatment, more than 50% were referred to our center by a physician, 36.7% by relatives or friends, whereas 10% did not receive any referral. In contrast, only 34.1% of noncompleters was referred by a physician, 36.4% was advised by relatives or friends, whereas 30% did not receive any referral (Fisher’s exact test; P = 0.036).

Psychometric characteristics of completers and noncompleters

Table 2 shows the psychometric characteristics of the entire study cohort, divided in completers and noncompleters. Compared with completers, subjects who did not complete the weight loss program had significantly higher scores at the SCL-90 anger-hostility subscale. Although there was a marginally significant difference in BES scores between the two groups, no other significant psychometric differences were found.

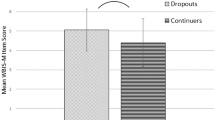

Weight loss

Independent of treatment length, 69 of the study participants (70.4%) showed weight loss, 23 (23.5%) did not show significant weight changes, whereas the remaining 6 subjects (6.1%) had weight gain (Figure 1). The weight loss was greater than 5% of the initial body weight in 43 of the study subjects (43.9%). The mean weight loss percentage was 4.1 ± 4.2% (ranging between +4.0% and -16.3%), whereas the mean early weight loss percentage was 2.5 ± 2.0% (ranging between from +2.0% to -8.8%). Compared with noncompleters, completers showed higher percentages of weight loss both at one month (-3.1 ± 2.1% vs. -1.8 ± 1.8%, P < 0.01) and at the end of treatment (-7.3 ± 4.1% vs. -1.7 ± 2.4%, P < 0.001).

Predictors of drop-out

A multivariable logistic regression analysis including pre-treatment variables (Table 3) showed that body fat percentage (P = 0.030) and the SCL-90 anger-hostility subscale (P = 0.021) were independently associated with an increased likelihood of attrition. The risk of drop-out was reduced by approximately 15% for each one percent increase in body fat, whereas there was a 4-fold increase in the risk of drop-out for each 1-point in the SCL-90 anger-hostility subscale. In a multivariable model considering both pre-treatment and treatment-related factors (Table 4), attrition was found to be independently related to the age at first dieting attempt (p = 0.016) and the achievement of early weight loss (p = 0.029). The risk of drop-out decreased by 11% for each 1-year increase in the age at the first dieting attempt. Moreover, the risk of drop-out was reduced by 40% for each 1-point percentage decrease in body weight at one month compared with baseline values.

Discussion

The identification and validation of reliable predictors of attrition would be helpful in reducing the drop-out from obesity treatment. In this study, we specifically aimed at identifying the predictors of drop-out focusing on theoretically- (e.g., psychopathological symptoms and dieting behaviors) or empirically-based (e.g., unsatisfactory early weight loss) factors.

Despite the higher drop-out rate (57% at 6 months) observed in our study, our findings are generally in line with those reported in recent studies with a similar treatment duration [5, 17, 31]. Our results indicate that few baseline variables (%BF, diastolic blood pressure, type of referral, and age at first dieting attempt) significantly differed between completers and noncompleters. It is conceivable that subjects with a higher awareness of their impaired health status may have a lower drop-out rate. Notably, obese subjects are characterized by a high prevalence of psychopathology [23] which may in turn have a significant impact on attrition. Interestingly, our results indicate that higher anger-hostility scores on the SCL-90 are associated with increased drop-out rates, suggesting that anger and anger expression styles may predict attrition among adult obese individuals wishing to lose weight. Different mechanisms may explain the relation between anger-hostility and an increased risk of drop-out. Burns and coworkers [32] reported that hostile patients are characterized by a negative set of expectations and tend to be suspicious of others [33]. Such a suspicious relational style may predispose them to reject the physician’s suggestions [34]. Negative expectations may also undermine the confidence with health care providers and lead to an inability to follow the clinician’s recommendations. Moreover, physicians may be alienated [32] by cynicism and hostility, which can in turn result in poor treatment engagement. Finally, hostility could also contribute to the likelihood of drop-out through its association with negative affect [35].

The high attrition rate (21.4%) observed in our study at one month highlights the paramount role played by baseline motivational status for predicting treatment discontinuation [31, 36]. In accordance with previous data [6], we found that the achievement of early weight loss may represent a strong motivational incentive for obtaining clinically meaningful weight loss goals. Taken together, these data confirm that the attrition rates in weight loss programs are not only related to psychopathological variables (i.e., anger) and age at first dieting attempt, but also to treatment-related factors such as the percentage of initial body weight lost after the first weeks of treatment [9]. It is likely that anger and hostility can act as upstream factors of early weight loss, i.e. individuals who show signs of anger will be less likely to comply with the weight loss regimen and therefore lose less weight early in the program. Additionally, both a lower stress threshold and a poorer capability to accept worse-than-expected outcomes (i.e., weight loss) could make those subjects abandon treatment before its completion. Notably, we found a borderline higher BES score in noncompleters, which may suggest a reduced self-control level towards food.

Several previous studies conducted in different settings have been designed to identify the potential baseline predictors of drop-out from obesity treatment. The findings from our current study are generally in agreement with the majority of previous reports in the field [3, 7–15, 17, 18] although the results were not always consistent [6, 8, 9, 12] and sporadically even were at variance [5, 11]. There are several potential reasons that may account for the discrepant findings across studies, including differences in the study settings, the number and characteristics of the subjects recruited, and the type of weight loss protocols.

Our report has some limitations that merit consideration. First, this study was based on a convenience sample, which limits the generalizability of its findings. Second, we did not specifically investigate the reasons of drop-out. Finally, our study was conducted on a limited number of Italian obese patients who were enrolled in an obesity treatment program in an outpatient academic setting; therefore, our results might not apply to different settings and need further validation before firm conclusions can be made.

Conclusion

In summary, the results from the current study indicate that baseline body fat percentage, SCL-90 anger-hostility subscale, and age at first attempt to diet were independent predictors of drop-out from treatment in an Italian cohort of adult obese subjects. Importantly, we also demonstrate that the achievement of early weight loss was independently associated with a reduced attrition rate. These results highlight the importance of a close clinical monitoring in the first weeks of treatment to reduce the attrition rates and make drop-out from obesity treatment not only predictable but also preventable. Future studies are needed to determine whether targeted psychological interventions may reduce attrition rates in obese subjects with significant anger and anger expression styles.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- %BF:

-

Percentage body fat

- WHR:

-

Waist-to-hip ratio

- SCL-90:

-

Symptoms checklist-90

- BDI:

-

Beck depression inventory

- BES:

-

Binge eating scale.

References

Moroshko I, Brennan L, O'Brien P: Predictors of dropout in weight loss interventions: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev. 2011, 12: 912-934. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00915.x.

Dansinger ML, Gleason JA, Griffith JL, et al: Comparison of the Atkins, Ornish, Weight Watchers, and Zone diets for weight loss and heart disease risk reduction; a randomized trial. JAMA. 2005, 293: 43-53. 10.1001/jama.293.1.43.

Gunnarsdóttir I, Sigurgeirsdóttir GK, Thórsdóttir I: Predictors of dropping out in a weight loss intervention trial. Ann Nutr Metab. 2010, 56: 212-10.1159/000279224. Epublication 11 March 2010

Lim SS, Norman RJ, Clifton PM, et al: Psychological effects of prescriptive vs. general lifestyle advice for weight loss in young women. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009, 109: 1917-1921. 10.1016/j.jada.2009.08.008.

Messier V, Hayek J, Karelis AD, et al: Anthropometric, metabolic, psychosocial and dietary factors associated with dropout in overweight and obese postmenopausal women engaged in a 6-month weight loss programme: a MONET study. Br J Nutr. 2010, 103: 1230-1235. Epublication 24 November 2009

Elfhag K, Rossner S: Initial weight loss is the best predictor for success in obesity treatment and sociodemographic liabilities increase risk of drop-out. Patient Educ Couns. 2010, 79: 361-366. 10.1016/j.pec.2010.02.006.

Chang MW, Brown R, Nitzke S: Participant recruitment and retention in a pilot program to prevent weight gain in low-income overweight and obese mothers. BMC Public Health. 2009, 9: 424-10.1186/1471-2458-9-424.

Inelmen EM, Toffanello ED, Enzi G, et al: Predictors of drop-out in overweight and obese outpatients. Int J Obes. 2005, 29: 122-128. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802846.

Fabricatore AN, Wadden TA, Moore RH, et al: Predictors of attrition and weight loss success: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. 2009, 47: 685-691. 10.1016/j.brat.2009.05.004. Epublication 20 May 2009

Gripeteg L, Karlsson J, Torgerson J, et al: Predictors of very-low-energy diet outcome in obese women and men. Obes Facts. 2010, 3: 159-165. Epublication 11 June 2010

Dalle Grave R, Calugi S, Molinari E, et al: Weight loss expectations in obese patients and treatment attrition: an observational multicenter study. Ob Res. 2005, 13: 1961-1969. 10.1038/oby.2005.241.

Bradshaw AJ, Horwath CC, Katzer L, et al: Non-dieting group interventions for overweight and obese women: what predicts non-completion and does completion improve outcomes?. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13: 1622-1628. 10.1017/S1368980009992977.

Greenberg I, Stampfer MJ, Schwarzfuchs D, et al: Adherence and success in long-term weight loss diets: the dietary intervention randomized controlled trial (DIRECT). J Am Coll Nutr. 2009, 28: 159-168. 10.1080/07315724.2009.10719767.

Busetto L, Mazza M, Salvalaio S, et al: Obesity treatment in elderly outpatients: predictors of efficacy and drop-out. Eat Weight Disord. 2009, 14: e56-e65. 10.1007/BF03327801.

Kong W, Langlois MF, Kamga-Ngandé C, et al: Predictors of success to weight-loss intervention program in individuals at high risk for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010, 90: 147-153. 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.06.031. Epublication 24 July 2010

De Panfilis C, Cero S, Dall’Aglio E, et al: Psychopathological predictors of compliance and outcome in weight-loss obesity treatment. Acta Biomed. 2007, 78: 22-28.

De Panfilis C, Torre M, Cero S, et al: Personality and attrition from behavioral weight-loss treatment for obesity. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008, 30: 515-520. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.06.003. Epublication 3 August 2008

Komulainen T, Keränen AM, Rasinaho E, et al: Quitting a weight loss program is associated with anhedonia: preliminary findings of the Lifestyle Intervention Treatment Evaluation Study in northern Finland. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2011, 70: 72-78. Epublication 16 February 2011

Somerset SM, Graham L, Markwell K: Depression scores predict adherence in a dietary weight loss intervention trial. Clin Nutr. 2011, 30: 593-598. 10.1016/j.clnu.2011.04.004. Epublication 14 May 2011

Marchesini G, Bellini M, Natale S, et al: Psychiatric distress and health-related quality of life in obesity. Diabetes Nutr Metab. 2003, 16: 145-154.

Onyike CU, Crum RM, Lee HB, et al: Is obesity associated with major depression? Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Epidemiol. 2003, 158: 1139-1147. 10.1093/aje/kwg275.

Scott KM, Bruffaerts R, Simon GE, et al: Obesity and mental disorders in the general population: results from the world mental health surveys. Int J Obes. 2008, 32: 192-200. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803701.

Martinelli V, Colombo O, Nichini C, et al: High frequency of psychopathology in subjects wishing to lose weight: an observational study in Italian subjects. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14: 373-376. 10.1017/S1368980010001576. Epublication 11 June 2010

Teixeira PJ, Scott BG, Houtkooper LB, et al: Weight loss readiness in middle-aged women: psychosocial predictors of success for behavioral weight reduction. J Behav Med. 2002, 25: 499-523. 10.1023/A:1020687832448.

Teixeira PJ, Palmeira AL, Branco TL, et al: Who will lose weight? A reexamination of predictors of weight loss in women. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2004, 1: 1-12. 10.1186/1479-5868-1-1.

NHLBI Obesity Education Initiative Expert Panel on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults: Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults – the evidence report. National Institutes of Health. Obes Res. 1998, 6: 51S-209S.

Italian Society of Human Nutrition: Recommended levels of assumption of energy and nutrients for the Italian population (LARN). 2012, Rome, [http://sinu.it/documenti/20121016_LARN_bologna_sintesi_prefinale.pdf]

Prunas A, Sarno I, Preti E, et al: Psychometric properties of the Italian version of the SCL-90-R: a study on a large community sample. Eur Psychiatry. 2012, 27: 591-597. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.12.006. Epublication 21 February 2011

Beck AT: Depression: Causes and treatment. 1967, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press

Gormally J, Black S, Daston S, et al: The assessment of binge eating severity among obese persons. Addict Behav. 1982, 7: 47-55. 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90024-7.

Minniti A, Bissoli L, Di Francesco V, et al: Individual versus group therapy for obesity: comparison of dropout rate and treatment outcome. Eat Weight Disord. 2007, 12: 161-167. 10.1007/BF03327593.

Burns JW, Higdon LJ, Mullen JT, et al: Relationships among patient hostility, anger expression, depression, and the working alliance in a work hardening program. Ann Behav Med. 1999, 21: 77-82. 10.1007/BF02895037.

Pope MK, Smith TW, Rhodewalt F: Cognitive, behavioral, and affective correlates of the Cook and Medley Hostility Scale. J Pers Assess. 1990, 54: 501-514. 10.1207/s15327752jpa5403&4_7.

Smith TW: Hostility and health: current status of a psychosomatic hypothesis. Health Psychol. 1992, 11: 139-150.

Pugh R: An association between hostility and poor adherence to treatment in patients suffering from depression. Br J Med Psychol. 1983, 56: 205-208. 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1983.tb01548.x.

Teixeira PJ, Silva MN, Mata J, et al: Motivation, self-determination, and long-term weight control. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012, 9: 22-10.1186/1479-5868-9-22.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

OC participated in the conception and design of the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript; FVV analysed and interpreted the data; CF participated in data collection and interpretation; CT participated in data collection and interpretation; PV participated in data collection and interpretation; SV supervised the design of the study, analyzed and interpreted the data; AT was responsible for the overall scientific direction and supervision. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Colombo, O., Ferretti, V.V.V., Ferraris, C. et al. Is drop-out from obesity treatment a predictable and preventable event?. Nutr J 13, 13 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-13-13

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-13-13