Abstract

Background

Obesity is a state of chronic low-grade inflammation. Chronic low-grade inflammation is associated with the pathophysiology of both type-2 diabetes and atherosclerosis. Prevention or reduction of chronic low-grade inflammation may be advantageous in relation to obesity related co-morbidity. In this study we investigated the acute effect of dietary protein sources on postprandial low-grade inflammatory markers after a high-fat meal in obese non-diabetic subjects.

Methods

We conducted a randomized, acute clinical intervention study in a crossover design. We supplemented a fat rich mixed meal with one of four dietary proteins - cod protein, whey isolate, gluten or casein. 11 obese non-diabetic subjects (age: 40-68, BMI: 30.3-42.0 kg/m2) participated and blood samples were drawn in the 4 h postprandial period. Adiponectin was estimated by ELISA methods and cytokines were analyzed by multiplex assay.

Results

MCP-1 and CCL5/RANTES displayed significant postprandial dynamics. CCL5/RANTES initially increased after all meals, but overall CCL5/RANTES incremental area under the curve (iAUC) was significantly lower after the whey meal compared with the cod and casein meals (P = 0.0053). MCP-1 was initially suppressed after all protein meals. However, the iAUC was significantly higher after whey meal compared to the cod and gluten meals (P = 0.04).

Conclusion

We have demonstrated acute differential effects on postprandial low grade inflammation of four dietary proteins in obese non-diabetic subjects. CCL5/RANTES initially increased after all meals but the smallest overall postprandial increase was observed after the whey meal. MCP-1 was initially suppressed after all 4 protein meals and the whey meal caused the smallest overall postprandial suppression.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT00863564

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The global incidence of obesity is escalating at epidemic proportions. The obesity related co-morbidities include increased incidence of the metabolic syndrome, type-2 diabetes (T2DM), hypertension, dyslipidaemia and chronic low-grade inflammation [1, 2].

Interestingly, Hotamisligil et al [3] in 1993 suggested that chronic low-grade inflammation plays a role in the pathophysiology of obesity in general and of insulin resistance in particular. This has subsequently been supported by the demonstration of a correlation between circulating levels of inflammatory markers and both T2DM [4] and atherosclerosis in humans [5–8].

White adipose tissue (WAT) is an important endocrine organ that secretes molecules, referred to as adipokines [9]. The chronic low-grade inflammation of obesity is characterized by increased concentrations of circulating inflammatory adipokines and cytokines [10–13]. Importantly, the inflammatory and metabolic pathways are linked. WAT is infiltrated with macrophages in response to adipocyte hypertrophy and the associated increase in monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) expression [14, 15]. Increased circulating concentrations of MCP-1 are in humans predictive of both diabetes risk independently of other traditional risk factors [16] and atherosclerosis [17, 18]. Furthermore, differentiation of monocytes into macrophages starts in plasma, when monocytes are activated in response to postprandial triglyceride rich lipoproteins [19, 20] and free fatty acids [21]. While MCP-1 is now regarded as a key inflammatory marker, CC chemokine ligand-5 (CCL5/RANTES) has in recent years emerged as a potentially therapeutic target in the prevention of atherosclerosis [22, 23]. The interaction between CCL5/RANTES and monocytes facilitates the adherence and transmigration of monocytes through the arterial wall [22] initiating the atherosclerotic process. CCL5/RANTES antagonisms have been demonstrated to reduce atherosclerotic lesions in mice [24]. Furthermore, CCL5/RANTES is up-regulated in WAT of obese compared to lean subjects [25] facilitating macrophage infiltration of adipose tissue.

Though, the impact of dietary protein on postprandial inflammation has not been thoroughly elucidated, the impact of diet in general on low-grade inflammation has been demonstrated (reviewed in [26]). Thus, a positive correlation to postprandial inflammation has been demonstrated for total energy intake in healthy men [27, 28] and a diet rich in saturated fat in overweight subjects [29]. Moreover dyslipidaemia characteristically for obesity, i.e. hypertriglyceridaemia, elevated apolipoprotein (Apo) B and small, dense low-density lipoproteins (LDL) has been positively correlated to low-grade inflammation in abdominally obese subjects with and without the metabolic syndrome [30]. The composition of meal fatty acids play an important role for low-grade inflammation in humans i.e. n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) being anti-inflammatory while n-6 PUFA and saturated fatty acids appear to be pro-inflammatory [31–33]. The impact of dietary carbohydrate on postprandial inflammation is controversial [26, 34].

Less is known about the influence of dietary protein on postprandial inflammation. Arya et al [35] demonstrated that meat with high fat content is more pro-inflammatory compared to lean meat in healthy subjects. Moreover, an inverse relationship has been demonstrated between dairy product consumption and low-grade inflammation in healthy subjects [36] and obese subjects [37].

We hypothesize that dietary protein sources may exert a differential impact on acute postprandial low-grade inflammation. In the present study we focused on the two inflammatory markers MCP-1 and CCL5/RANTES. As cod protein, gluten, casein and whey protein have been demonstrated to elicit differential postprandial lipid, glucose and hormone responses in healthy [38], overweight [39] and type-2 diabetic subjects [40] these four protein sources originating from fish, crops and milk may be suitable for assessing the impact of dietary protein on postprandial low-grade inflammation. The differential impact of the four protein sources on postprandial triglycerides and insulin may particularly reveal correlated differential responses on postprandial low-grade inflammation.

Subjects and methods

11 obese Caucasian subjects (8 postmenopausal women and 3 men) were recruited after advertising in local newspapers. All subjects had a body mass index (BMI) above 30 and all subjects were non-diabetics according to fasting plasma glucose < 7.0 mmol/l. Subjects with impaired fasting glucose were subjected to an oral glucose tolerance test and were excluded if the 2 h plasma glucose level was ≥ 11.1 mmol/l. No participant took medication with impact on lipids, inflammation, immune system or insulin sensitivity and all participants were non-smokers. No change in concomitant medication was allowed during the trial. Subject characteristics are shown in Table 1. All subjects gave written informed consent and the study was approved by The Committees on Biomedical Research Ethics for the Central Region of Denmark. This study was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (ID: NCT00863564).

Study design

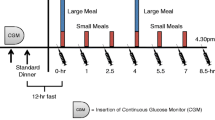

We performed a nested randomized, acute clinical intervention study. All subjects ingested four different meals on four different days with a washout period of two weeks between meals. Each subject was randomized to one of four meal sequences based on a Latin square design. Before each test day the subjects were given and consumed a standard diet with the following energy distribution: 56% energy from carbohydrate, 24% energy from fat and 20% energy from protein. The energy content was 7 000 kJ for women and 9 000 kJ for men. All subjects were asked to refrain from alcohol consumption and exercise in the 24 h preceding the test day. In the morning after a 12 h fasting period a catheter was inserted into an antecubital vein. After 15 min of rest baseline samples were drawn. The test meal was served and ingested within 20 min and blood samples for inflammatory markers were drawn in the 4 h postprandial period. The subjects were allowed to drink tap water ad libitum. Plasma was separated immediately by centrifugation at 2 000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. Plasma samples were stored at -80°C until analyzed.

Test meals

All subjects consumed in random order four fat rich test meals containing 4971 - 4986 KJ with 19 E% carbohydrate, 66 E% fat and 15 E% protein, respectively. All test meals consisted of an energy free soup with an added 100 g of butter (Lurpak; Arla Foods amba, Viby J, Denmark) corresponding to 80 g of fat (68% of energy as saturated fat). 45 g of carbohydrate was added as white wheat bread (Läntmann Schulstad A/S, Hvidovre, Denmark) and 45 g of a protein preparation was added or served with the meal. The protein sources were cod, whey isolate, gluten and casein. The 45 g of cod protein (cod meal) corresponded to 285 g of minced cod filet (Coop torskefilet; Royal Greenland A/S, Aalborg, Denmark). This was added to the soup before heating. The spray dried whey isolate (whey meal) (Lacprodan DI-9224; kindly provided by Arla Foods Ingredients amb, Viby J, Denmark) was dissolved in 200 ml water and served with the meal. Gluten (gluten meal) (Gluvital 21000; kindly provided by Cerestar Scandinavia A/S, Charlottenlund, Denmark) was mixed into the soup before heating. Casein (casein meal) was applied as spray dried calcium caseinate (Miprodan 40; kindly provided by Arla Foods Ingredients amba, Viby J, Denmark). Half of the casein was dissolved in water and the other half was added to the soup before heating. To make the soup more palatable we added 25 g of sliced raw leek, 1 g of curry and ½ dice of chicken bouillon. The soup had a serving temperature of 65°C. The total amount of water in each meal was 675 ml and the total volume of each meal did not differ.

Blood analyses

Adiponectin was measured using the B-Bridge Int. human adiponectin enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay (ELISA) kit (Cat# K1001-1), (CV: 3.2%). All other inflammatory markers were assessed using a fixed Bio-Plex Pro Human Cytokine 27-plex array (Cat# M50-0KCAF0Y) according to manufacturer's instructions, (CV: 5-15%) as described previously [33, 41]. Plasma samples were diluted 1:2 and incubated with anti-cytokine antibody-coupled beads for 30 min at room temperature. Beads were then incubated with biotinylated detection antibodies for 30 min, before incubation with Streptavidin-phycoerythrin for 30 min. Following each incubation step, complexes were washed 3 times in wash buffer using the Bio-Plex Pro Wash Station. Finally, complexes were resuspended in 125 μl of assay buffer, and beads were counted on the Bio-Plex 200 system (Bio-Rad). Duplicates were performed. Mean fluorescence intensity was analyzed and data was given as pg/ml. The 27-plex array included the following cytokines: Interleukine (IL)-1b, IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra), IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-9, IL-10, IL-12 (p70), IL-13, IL-15, IL-17A, basic fibroblast growth factor (basic FGF), eotaxin, granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), interferon-γ (IFN-γ), IFN-γ induced protein 10 kDa (IP-10), MCP-1, macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α), MIP-1β, platelet derived growth factor BB (PDGF-BB), CCL5/RANTES, Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).

Statistical analysis and calculations

Comparisons were based on a mixed effects model [42] (STATA/IC 10.1) using treatment group as fixed variable and participant ID as random variable. All estimates were adjusted for treatment order, baseline values, gender and waist-to-hip ratio. F-test or Wald test were applied as appropriate. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Any statistical significant main effect of meal was followed up by Tukey's post hoc correction for pair wise comparison. Whenever data was not normally distributed, a log transformation was performed and the statistical analysis was carried out on the normal distributed log data. Data was given as net incremental area under the curve (iAUC) 0-240 min. Net iAUC was calculated using trapezoidal rule. Data was given as means ± SD in tables and as means ± SE in graphs unless otherwise stated. When statistical analyses were performed on log transformed data, results were given as medians with interquartile ranges. Any sample with a value below detection limit was omitted from the statistical analyses. No statistical analyses were performed on cytokines with more than 9% of samples below detection limit: IL-1b, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-9, IL-10, IL-12 (p70), IL-13, IL-15, IL-17A, basic FGF, GM-CSF, MIP-1α and TNF-α.

Results

The 11 obese non-diabetic subjects completed the four test meals according to protocol. No significant differences in fasting cytokines concentrations were found (Table 2). No significant weight changes were found between first (100.5 kg) and last (100.4 kg) test day.

CCL5/RANTES

The plasma concentrations of CCL5/RANTES increased for all meals at 30 min (Figure 1). The average increment at 30 min was 86%. Towards the end of the observation period CCL5/RANTES concentrations decreased towards baseline for all meals. At 240 min CCL5/RANTES concentration after cod-meal was 52% above baseline whereas CCL5/RANTES concentration after whey-meal was 39% below baseline. We found a statistically significant main effect of meal (P = 0.0053). The iAUC-240 min was lower after whey-meal compared to cod meal and casein meal. The iAUC-240 min was also lower after gluten meal compared to cod meal (Table 2). Post hoc analyses did not demonstrate differences between meals in CCL5/RANTES iAUC-60 min (P = 0.55). However, a negative correlation was demonstrated between insulin iAUC-240 min and CCL5/RANTES iAUC-240 min (r = -0.33; P = 0.04). No post hoc correlation could be demonstrated between triglycerides and MCP-1 (data not presented).

The plot show mean (+SEM) responses for CCL5/RANTES in plasma in the 4 h postprandial period after the four meals consumed by 11 obese non-diabetic subjects. Meals consisted of an energy-free soup plus 80 g fat (from butter) and 45 g carbohydrate consumed with either 45 g cod protein, 45 g whey protein, 45 g gluten or 45 g casein.

MCP-1

MCP-1 plasma levels decreased for all meals in the first 30 min (Figure 2). The mean decrement at 30 min was 17%. Towards the end of the observation period MCP-1 levels after whey-meal reached baseline whereas MCP-1 concentrations only slightly increased but remained below baseline for the three other meals. We found a statistically significant main effect of meal (P = 0.040). The overall net suppression of MCP-1 was smaller for whey-meal compared to cod-meal and gluten-meal (Table 2). Post hoc analyses did not demonstrate differences between meals in MCP-1 iAUC-60 min (P = 0.38). However, a post hoc correlation analysis revealed a positive correlation between insulin iAUC-240 min and MCP-1 iAUC-240 min (r = 0.39; P = 0.01). No post hoc correlation could be demonstrated between triglycerides and MCP-1 (data not presented).

The plot show mean (+SEM) responses for MCP-1 in plasma in the 4 h postprandial period after the four meals consumed by 11 obese non-diabetic subjects. Meals consisted of an energy-free soup plus 80 g fat (from butter) and 45 g carbohydrate consumed with either 45 g cod protein, 45 g whey protein, 45 g gluten or 45 g casein.

Other cytokines

No significant differences between meals were observed for IFN-γ, adiponectin, eotaxin, G-CSF, IP-10, MIP-1β, PDGF-BB, IL-1ra and VEGF, respectively (Table 2).

Discussion

We have demonstrated acute differential effects of dietary protein sources on postprandial low-grade inflammation after a high-fat meal in obese non-diabetic subjects. Of particular interest we observed that MCP-1 and CCL5/RANTES displayed acute postprandial responses to the test meals. MCP-1 was initially suppressed and CCL5/RANTES initially increased after consumption of the test meals. For both cytokines no significant differences between meals were evident at peak values after 60 min. However, whey-meal was associated with a different overall response after 240 min compared to the other protein meals. MCP-1 was suppressed to a smaller extent after whey-meal compared to cod-meal and gluten-meal. CCL5/RANTES iAUC-240 min was smaller after the whey-meal compared to the other meals - in particular compared to cod-meal and casein-meal.

Several studies have demonstrated postprandial adherence of Apo B to monocytes and activation of monocytes in response to an oral fat loading test in healthy subjects [19, 20]. The activation of monocytes is important for the endothelial adhesion of monocytes and subsequent transmigration across the endothelial wall where the monocytes differentiate into macrophages [43]. However, this process is further enhanced when oxidized LDL and chylomicron remnant particles are taken up by residing macrophages inside the vessel wall. These macrophages activate the endothelium to produce MCP-1 which in mice resulted in further localized recruitment and tissue infiltration of monocytes [44]. In the endothelial wall the phagocytosis of oxidized lipoproteins by macrophages precedes the development of atherosclerotic plaques. Consequently any means to reduce endothelial adhesion of monocytes may reduce the progression of atherosclerotic plaques.

The CCL5/RANTES response was significantly smaller after whey meal compared to the cod and casein meals. Krohn et al [45] demonstrated reduction of neointimal thickening and macrophage infiltration in CCL5/RANTES knock-out mice. These findings are consistent with the CCL5/RANTES antagonist study of Braunersreuther et al [46] who also demonstrated that deficiency of the CCL5/RANTES receptor protects Apo E -/- mice from diet induced atherosclerosis [47]. The finding of up-regulated CCL5/RANTES in human atherosclerotic plaques [48] corroborates with the association demonstrated between CCL5/RANTES and unstable angina pectoris [49] and myocardial infarction [50]. While CCL5/RANTES is thought to be crucial to monocyte recruitment during development of atherosclerosis [51] high density lipoprotein may partly cause its cardioprotective effect by reducing circulating levels of CCL5/RANTES [52]. Furthermore, high levels of CCL5/RANTES had a positive correlation to the development of T2DM in humans [53].

In the present study cod protein and gluten induced significantly lower concentrations of MCP-1 compared to whey protein. The mechanism of action is not known. However, in the cod-meal the total quantity of n-3 fatty acids was 752 mg, which may contribute to the anti-inflammatory effects via interaction with the pro-inflammatory transcription factor i.e. nuclear factor kappa beta (NF-κB) [54, 55]. However, since gluten does not contain any n-3 fatty acids it may be speculated that cod and gluten do not share particular MCP-1 lowering properties. MCP-1 may be higher after whey meal due to whey specific properties e.g. higher insulin response as discussed later.

Research on the immunomodulatory properties of milk proteins has traditionally been focusing on the antimicrobial effects of T-cells, macrophages and the innate immune response [56]. The availability of immunomodulatory peptides is not solely depending on the dietary composition but also varies depending on the specific enzymatic digestion of milk components in the intestinal tractus [57]. Aihara et al [58] demonstrated that the casein and whey derived tri-peptide valyl-prolyl-proline modulates monocyte adhesion to inflamed endothelia in vitro via attenuation of the pro-inflammatory c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK) pathway. Interestingly, the casein subunit "α s1" is expressed by monocytes in vitro [59] promoting a pro-inflammatory cytokine response. Furthermore, Zemel et al [36] demonstrated reduced levels of MCP-1 after a dairy rich diet but not after a soy rich diet in a 28 day intervention period. These observations support that circulating peptides from a dairy product rich diet may at least in part be responsible for the differential cytokine responses observed after the four meals in the present study.

Whey protein reduces postprandial lipaemia more than cod, gluten and casein [39, 40]. However, we could not demonstrate any correlation between postprandial lipaemia and the inflammatory markers.

Euglycemic hyperinsulineamia has been found to inhibit NF-κB and reduce concentrations of MCP-1 in obese subjects after 2 h and 4 h of insulin infusion [60, 61]. As whey protein is more insulinotropic than cod protein, gluten and casein this mechanism would imply a larger suppression of MCP-1 after the whey meal compared to the other meals. However, we have demonstrated a positive correlation between postprandial insulin and MCP-1 as well as a negative correlation between postprandial insulin and CCL5/RANTES. This is in accordance with our findings that the MCP-1 iAUC-240 min for the whey meal was larger compared to the other meals and that the CCL5/RANTES iAUC-240 min was smaller after whey meal. Other studies have demonstrated anti-inflammatory properties of insulin infusion on both MCP-1 and CCL5/RANTES [62]. We cannot explain the opposing effects of whey meal on MCP-1 and CCL5/RANTES in our study.

Conclusion

MCP-1 and CCL5/RANTES are risk markers closely associated to obesity related risk factors, i.e. dyslipidaemia and insulin resistance. Long-term studies are needed to establish the potentially clinical effect of the impact of dietary protein on postprandial low-grade inflammation. In the present study we demonstrated an inverse relationship between concentrations of postprandial MCP-1 and CCL5/RANTES after the cod, whey isolate, gluten and casein meals.

This study is an exploratory pilot study indicating differential effects of dietary protein sources on postprandial inflammatory cytokines. Inclusion of different protein rich foods may enhance or diminish the inflammatory properties of a given diet. As circulating concentrations of MCP-1 and CCL5/RANTES are profoundly affected in the postprandial period, future research on postprandial low-grade inflammation should include these key inflammatory markers.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations

- Apo:

-

apo protein

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- CCL5:

-

CC chemokine ligand-5

- ELISA:

-

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FGF:

-

fibroblast growth factor

- G-CSF:

-

granulocyte colony stimulating factor

- GM-CSF:

-

granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor

- iAUC:

-

incremental area under the curve

- IFN-γ:

-

interferon-γ

- IL:

-

interleukine

- IL-1ra:

-

IL-1 receptor antagonist

- IP-10:

-

interferon-γ induced protein 10 kDa

- JNK:

-

c-Jun N-terminal kinases

- LDL:

-

low density lipoproteins

- MCP-1:

-

monocyte chemotactic protein-1

- MIP-1α:

-

macrophage inflammatory protein-1α

- NF-κB:

-

nuclear factor kappa beta

- PDGF-BB:

-

platelet derived growth factor BB

- PUFA:

-

poly unsaturated fatty acids

- RANTES:

-

regulated upon activation normal

- T-cell:

-

expressed and secreted

- T2DM:

-

type 2 diabetes

- TNF-α:

-

tumor necrosis factor-α

- VEGF:

-

vascular endothelial growth factor

- WAT:

-

white adipose tissue.

References

Biro FM, Wien M: Childhood obesity and adult morbidities. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010, 91: 1499S-1505S. 10.3945/ajcn.2010.28701B.

Schelbert KB: Comorbidities of obesity. Prim Care. 2009, 36: 271-285. 10.1016/j.pop.2009.01.009.

Hotamisligil GS, Shargill NS, Spiegelman BM: Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha: direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Science. 1993, 259: 87-91. 10.1126/science.7678183.

Pradhan AD, Manson JE, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM: C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2001, 286: 327-334. 10.1001/jama.286.3.327.

Ridker PM, Buring JE, Cook NR, Rifai N: C-reactive protein, the metabolic syndrome, and risk of incident cardiovascular events: an 8-year follow-up of 14 719 initially healthy American women. Circulation. 2003, 107: 391-397. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000055014.62083.05.

Libby P, Ridker PM, Hansson GK, Leducq Transatlantic Network on Atherothrombosis: Inflammation in atherosclerosis: from pathophysiology to practice. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009, 54: 2129-2138. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.09.009.

Danesh J, Wheeler JG, Hirschfield GM, Eda S, Eiriksdottir G, Rumley A, Lowe GD, Pepys MB, Gudnason V: C-reactive protein and other circulating markers of inflammation in the prediction of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2004, 350: 1387-1397. 10.1056/NEJMoa032804.

Danesh J, Kaptoge S, Mann AG, Sarwar N, Wood A, Angleman SB, Wensley F, Higgins JP, Lennon L, Eiriksdottir G, Rumley A, Whincup PH, Lowe GD, Gudnason V: Long-Term Interleukin-6 Levels and Subsequent Risk of Coronary Heart Disease: Two New Prospective Studies and a Systematic Review. PLoS Med. 2008, 5: e78-10.1371/journal.pmed.0050078.

Wang P, Mariman E, Renes J, Keijer J: The secretory function of adipocytes in the physiology of white adipose tissue. J Cell Physiol. 2008, 216: 3-13. 10.1002/jcp.21386.

Yudkin JS, Stehouwer CD, Emeis JJ, Coppack SW: C-reactive protein in healthy subjects: associations with obesity, insulin resistance, and endothelial dysfunction: a potential role for cytokines originating from adipose tissue?. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999, 19: 972-978. 10.1161/01.ATV.19.4.972.

Festa A, D'Agostino R, Williams K, Karter AJ, Mayer-Davis EJ, Tracy RP, Haffner SM: The relation of body fat mass and distribution to markers of chronic inflammation. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001, 25: 1407-1415. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801792.

Park HS, Park JY, Yu R: Relationship of obesity and visceral adiposity with serum concentrations of CRP, TNF-alpha and IL-6. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2005, 69: 29-35. 10.1016/j.diabres.2004.11.007.

Fain JN: Release of inflammatory mediators by human adipose tissue is enhanced in obesity and primarily by the nonfat cells: a review. Mediators Inflamm. 2010, 2010: 513948-

Ito A, Suganami T, Miyamoto Y, Yoshimasa Y, Takeya M, Kamei Y, Ogawa Y: Role of MAPK phosphatase-1 in the induction of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 during the course of adipocyte hypertrophy. J Biol Chem. 2007, 282: 25445-25452. 10.1074/jbc.M701549200.

Sell H, Eckel J: Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 and its role in insulin resistance. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2007, 18: 258-262. 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3281338546.

Herder C, Baumert J, Thorand B, Koenig W, de Jager W, Meisinger C, Illig T, Martin S, Kolb H: Chemokines as risk factors for type 2 diabetes: results from the MONICA/KORA Augsburg study, 1984-2002. Diabetologia. 2006, 49: 921-929. 10.1007/s00125-006-0190-y.

Niu J, Kolattukudy PE: Role of MCP-1 in cardiovascular disease: molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Clin Sci (Lond). 2009, 117: 95-109. 10.1042/CS20080581.

Aukrust P, Halvorsen B, Yndestad A, Ueland T, Oie E, Otterdal K, Gullestad L, Damas JK: Chemokines and cardiovascular risk. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008, 28: 1909-1919. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.161240.

van Oostrom AJ, Rabelink TJ, Verseyden C, Sijmonsma TP, Plokker HW, De Jaegere PP, Cabezas MC: Activation of leukocytes by postprandial lipemia in healthy volunteers. Atherosclerosis. 2004, 177: 175-182. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.07.004.

Alipour A, van Oostrom AJ, Izraeljan A, Verseyden C, Collins JM, Frayn KN, Plokker TW, Elte JW, Cabezas MC: Leukocyte Activation by Triglyceride-Rich Lipoproteins. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008

Bouwens M, Grootte Bromhaar M, Jansen J, Muller M, Afman LA: Postprandial dietary lipid-specific effects on human peripheral blood mononuclear cell gene expression profiles. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010, 91: 208-217. 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28586.

Huo Y, Schober A, Forlow SB, Smith DF, Hyman MC, Jung S, Littman DR, Weber C, Ley K: Circulating activated platelets exacerbate atherosclerosis in mice deficient in apolipoprotein E. Nat Med. 2003, 9: 61-67. 10.1038/nm810.

Koenen RR, von Hundelshausen P, Nesmelova IV, Zernecke A, Liehn EA, Sarabi A, Kramp BK, Piccinini AM, Paludan SR, Kowalska MA, Kungl AJ, Hackeng TM, Mayo KH, Weber C: Disrupting functional interactions between platelet chemokines inhibits atherosclerosis in hyperlipidemic mice. Nat Med. 2009, 15: 97-103. 10.1038/nm.1898.

Veillard NR, Kwak B, Pelli G, Mulhaupt F, James RW, Proudfoot AE, Mach F: Antagonism of RANTES receptors reduces atherosclerotic plaque formation in mice. Circ Res. 2004, 94: 253-261. 10.1161/01.RES.0000109793.17591.4E.

Wu H, Ghosh S, Perrard XD, Feng L, Garcia GE, Perrard JL, Sweeney JF, Peterson LE, Chan L, Smith CW, Ballantyne CM: T-cell accumulation and regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted upregulation in adipose tissue in obesity. Circulation. 2007, 115: 1029-1038. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.638379.

Galland L: Diet and inflammation. Nutr Clin Pract. 2010, 25: 634-640. 10.1177/0884533610385703.

Amar J, Burcelin R, Ruidavets JB, Cani PD, Fauvel J, Alessi MC, Chamontin B, Ferrieres J: Energy intake is associated with endotoxemia in apparently healthy men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008, 87: 1219-1223.

Heinonen MV, Laaksonen DE, Karhu T, Karhunen L, Laitinen T, Kainulainen S, Rissanen A, Niskanen L, Herzig KH: Effect of diet-induced weight loss on plasma apelin and cytokine levels in individuals with the metabolic syndrome. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2009, 19: 626-633. 10.1016/j.numecd.2008.12.008.

van Dijk SJ, Feskens EJ, Bos MB, Hoelen DW, Heijligenberg R, Bromhaar MG, de Groot LC, de Vries JH, Muller M, Afman LA: A saturated fatty acid-rich diet induces an obesity-linked proinflammatory gene expression profile in adipose tissue of subjects at risk of metabolic syndrome. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009, 90: 1656-1664. 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27792.

Rogowski O, Shapira I, Steinvil A, Berliner S: Low-grade inflammation in individuals with the hypertriglyceridemic waist phenotype: another feature of the atherogenic dysmetabolism. Metabolism. 2009, 58: 661-667. 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.01.005.

Margioris AN: Fatty acids and postprandial inflammation. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2009, 12: 129-137. 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3283232a11.

Jimenez-Gomez Y, Lopez-Miranda J, Blanco-Colio LM, Marin C, Perez-Martinez P, Ruano J, Paniagua JA, Rodriguez F, Egido J, Perez-Jimenez F: Olive oil and walnut breakfasts reduce the postprandial inflammatory response in mononuclear cells compared with a butter breakfast in healthy men. Atherosclerosis. 2009, 204: e70-6. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.09.011.

Myhrstad MC, Narverud I, Telle-Hansen VH, Karhu T, Bodtker Lund D, Herzig KH, Makinen M, Halvorsen B, Retterstol K, Kirkhus B, Granlund L, Holven KB, Ulven SM: Effect of the fat composition of a single high-fat meal on inflammatory markers in healthy young women. Br J Nutr. 2011, 1-10.

Huffman KM, Orenduff MC, Samsa GP, Houmard JA, Kraus WE, Bales CW: Dietary carbohydrate intake and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein in at-risk women and men. Am Heart J. 2007, 154: 962-968. 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.07.009.

Arya F, Egger S, Colquhoun D, Sullivan D, Pal S, Egger G: Differences in postprandial inflammatory responses to a 'modern' v. traditional meat meal: a preliminary study. Br J Nutr. 2010, 104: 724-728. 10.1017/S0007114510001042.

Zemel MB, Sun X, Sobhani T, Wilson B: Effects of dairy compared with soy on oxidative and inflammatory stress in overweight and obese subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010, 91: 16-22. 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28468.

Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos CH, Zampelas AD, Chrysohoou CA, Stefanadis CI: Dairy products consumption is associated with decreased levels of inflammatory markers related to cardiovascular disease in apparently healthy adults: the ATTICA study. J Am Coll Nutr. 2010, 29: 357-364.

Nilsson M, Stenberg M, Frid AH, Holst JJ, Bjorck IM: Glycemia and insulinemia in healthy subjects after lactose-equivalent meals of milk and other food proteins: the role of plasma amino acids and incretins. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004, 80: 1246-1253.

Pal S, Ellis V, Ho S: Acute effects of whey protein isolate on cardiovascular risk factors in overweight, post-menopausal women. Atherosclerosis. 2010, 212: 339-344. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.05.032.

Mortensen LS, Hartvigsen ML, Brader LJ, Astrup A, Schrezenmeir J, Holst JJ, Thomsen C, Hermansen K: Differential effects of protein quality on postprandial lipemia in response to a fat-rich meal in type 2 diabetes: comparison of whey, casein, gluten, and cod protein. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009, 90: 41-48. 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27281.

Lehto SM, Niskanen L, Herzig KH, Tolmunen T, Huotari A, Viinamaki H, Koivumaa-Honkanen H, Honkalampi K, Ruotsalainen H, Hintikka J: Serum chemokine levels in major depressive disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010, 35: 226-232. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.06.007.

Rabe-Hesketh S: Multilevel and longitudinal modeling using Stata. 2008, Texas: Stata Press

Alipour A, Elte JW, van Zaanen HC, Rietveld AP, Cabezas MC: Postprandial inflammation and endothelial dysfuction. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007, 35: 466-469. 10.1042/BST0350466.

Grewal IS, Rutledge BJ, Fiorillo JA, Gu L, Gladue RP, Flavell RA, Rollins BJ: Transgenic monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) in pancreatic islets produces monocyte-rich insulitis without diabetes: abrogation by a second transgene expressing systemic MCP-1. J Immunol. 1997, 159: 401-408.

Krohn R, Raffetseder U, Bot I, Zernecke A, Shagdarsuren E, Liehn EA, van Santbrink PJ, Nelson PJ, Biessen EA, Mertens PR, Weber C: Y-box binding protein-1 controls CC chemokine ligand-5 (CCL5) expression in smooth muscle cells and contributes to neointima formation in atherosclerosis-prone mice. Circulation. 2007, 116: 1812-1820. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.708016.

Braunersreuther V, Steffens S, Arnaud C, Pelli G, Burger F, Proudfoot A, Mach F: A novel RANTES antagonist prevents progression of established atherosclerotic lesions in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008, 28: 1090-1096. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.165423.

Braunersreuther V, Zernecke A, Arnaud C, Liehn EA, Steffens S, Shagdarsuren E, Bidzhekov K, Burger F, Pelli G, Luckow B, Mach F, Weber C: Ccr5 but not Ccr1 deficiency reduces development of diet-induced atherosclerosis in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007, 27: 373-379.

Breland UM, Michelsen AE, Skjelland M, Folkersen L, Krohg-Sorensen K, Russell D, Ueland T, Yndestad A, Paulsson-Berne G, Damas JK, Oie E, Hansson GK, Halvorsen B, Aukrust P: Raised MCP-4 levels in symptomatic carotid atherosclerosis: an inflammatory link between platelet and monocyte activation. Cardiovasc Res. 2010, 86: 265-273. 10.1093/cvr/cvq044.

Kraaijeveld AO, de Jager SC, de Jager WJ, Prakken BJ, McColl SR, Haspels I, Putter H, van Berkel TJ, Nagelkerken L, Jukema JW, Biessen EA: CC chemokine ligand-5 (CCL5/RANTES) and CC chemokine ligand-18 (CCL18/PARC) are specific markers of refractory unstable angina pectoris and are transiently raised during severe ischemic symptoms. Circulation. 2007, 116: 1931-1941. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.706986.

Kobusiak-Prokopowicz M, Orzeszko J, Mazur G, Mysiak A, Orda A, Poreba R, Mazurek W: Chemokines and left ventricular function in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Eur J Intern Med. 2007, 18: 288-294. 10.1016/j.ejim.2007.02.001.

Jones KL, Maguire JJ, Davenport AP: Chemokine receptor CCR5: from AIDS to atherosclerosis. Br J Pharmacol. 2011, 162: 1453-1469. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01147.x.

Bursill CA, Castro ML, Beattie DT, Nakhla S, van der Vorst E, Heather AK, Barter PJ, Rye KA: High-density lipoproteins suppress chemokines and chemokine receptors in vitro and in vivo. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010, 30: 1773-1778. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.211342.

Herder C, Peltonen M, Koenig W, Kraft I, Muller-Scholze S, Martin S, Lakka T, Ilanne-Parikka P, Eriksson JG, Hamalainen H, Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi S, Valle TT, Uusitupa M, Lindstrom J, Kolb H, Tuomilehto J: Systemic immune mediators and lifestyle changes in the prevention of type 2 diabetes: results from the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study. Diabetes. 2006, 55: 2340-2346. 10.2337/db05-1320.

De Caterina R, Massaro M: Omega-3 fatty acids and the regulation of expression of endothelial pro-atherogenic and pro-inflammatory genes. J Membr Biol. 2005, 206: 103-116. 10.1007/s00232-005-0783-2.

Adkins Y, Kelley DS: Mechanisms underlying the cardioprotective effects of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. J Nutr Biochem. 2010, 21: 781-792. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.12.004.

Clare DA, Swaisgood HE: Bioactive milk peptides: a prospectus. J Dairy Sci. 2000, 83: 1187-1195. 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(00)74983-6.

Otani H, Hata I: Inhibition of proliferative responses of mouse spleen lymphocytes and rabbit Peyer's patch cells by bovine milk caseins and their digests. J Dairy Res. 1995, 62: 339-348. 10.1017/S0022029900031034.

Aihara K, Ishii H, Yoshida M: Casein-derived tripeptide, Val-Pro-Pro (VPP), modulates monocyte adhesion to vascular endothelium. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2009, 16: 594-603. 10.5551/jat.729.

Vordenbaumen S, Braukmann A, Petermann K, Scharf A, Bleck E, von Mikecz A, Jose J, Schneider M: Casein alpha s1 is expressed by human monocytes and upregulates the production of GM-CSF via p38 MAPK. J Immunol. 2011, 186: 592-601. 10.4049/jimmunol.1001461.

Dandona P, Aljada A, Mohanty P, Ghanim H, Hamouda W, Assian E, Ahmad S: Insulin inhibits intranuclear nuclear factor kappaB and stimulates IkappaB in mononuclear cells in obese subjects: evidence for an anti-inflammatory effect?. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001, 86: 3257-3265. 10.1210/jc.86.7.3257.

Aljada A, Ghanim H, Saadeh R, Dandona P: Insulin inhibits NFkappaB and MCP-1 expression in human aortic endothelial cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001, 86: 450-453. 10.1210/jc.86.1.450.

Ghanim H, Korzeniewski K, Sia CL, Abuaysheh S, Lohano T, Chaudhuri A, Dandona P: Suppressive effect of insulin infusion on chemokines and chemokine receptors. Diabetes Care. 2010, 33: 1103-1108. 10.2337/dc09-2193.

Acknowledgements

This work is carried out as a part of the research program of the Danish Obesity Research Centre (DanORC, see http://www.danorc.dk) and is supported by Nordic Centre of Excellence (NCoE) programme (Systems biology in controlled dietary interventions and cohort studies - SYSDIET, P No., 070014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

JHJ, TK, KHH and KH designed the study. JHJ and LSM recruited subjects and collected the data. SBP, TK and KHH performed the blood analyses. JHJ performed the data analysis. JHJ was responsible for drafting the manuscript; KH assisted with the editing of the manuscript. JHJ had primary responsibility for final content. All authors participated in the discussion of the results and commented on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Holmer-Jensen, J., Karhu, T., Mortensen, L.S. et al. Differential effects of dietary protein sources on postprandial low-grade inflammation after a single high fat meal in obese non-diabetic subjects. Nutr J 10, 115 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-10-115

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-10-115