Abstract

Background

Control of the major African malaria vector species continues to rely extensively on the application of residual insecticides through indoor house spraying or bed net impregnation. Insecticide resistance is undermining the sustainability of these control strategies. Alternatives to the currently available conventional chemical insecticides are, therefore, urgently needed. Use of fungal pathogens as biopesticides is one such possibility. However, one of the challenges to the approach is the potential influence of varied environmental conditions and target species that could affect the efficacy of a biological 'active ingredient'. An initial investigation into this was carried out to assess the susceptibility of insecticide-susceptible and resistant laboratory strains and wild-collected Anopheles arabiensis mosquitoes to infection with the fungus Beauveria bassiana under two different laboratory temperature regimes.

Methods

Insecticide susceptibility to all four classes of insecticides recommended by WHO for vector control was tested on laboratory and wild-caught An. arabiensis, using standard WHO bioassay protocols. Mosquito susceptibility to fungus infection was tested using dry spores of B. bassiana under two temperature regimes (21 ± 1°C or 25 ± 2°C) representative of indoor conditions observed in western Kenya. Cox regression analysis was used to assess the effect of fungal infection on mosquito survival and the effect of insecticide resistance status and temperature on mortality rates following fungus infection.

Results

Survival data showed no relationship between insecticide susceptibility and susceptibility to B. bassiana. All tested colonies showed complete susceptibility to fungal infection despite some showing high resistance levels to chemical insecticides. There was, however, a difference in fungus-induced mortality rates between temperature treatments with virulence significantly higher at 25°C than 21°C. Even so, because malaria parasite development is also known to slow as temperatures fall, expected reductions in malaria transmission potential due to fungal infection under the cooler conditions would still be high.

Conclusions

These results provide evidence that the entomopathogenic fungus B. bassiana has potential for use as an alternative vector control tool against insecticide-resistant mosquitoes under conditions typical of indoor resting environments. Nonetheless, the observed variation in effective virulence reveals the need for further study to optimize selection of isolates, dose and use strategy in different eco-epidemiological settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Malaria vector control relies primarily on the selective application of residual insecticides through either indoor residual house spraying (IRS) or insecticide-treated nets (ITNs). At high coverage, these approaches have proven highly effective in reducing malaria morbidity and mortality at an affordable cost [1]. However, the ever-increasing development of resistance to insecticides [2, 3] is of great concern. Insecticide resistance in malaria vector populations covers all classes of insecticides currently used in public health and is widespread geographically [2, 4–7]. It is, therefore, not surprising that interest in alternative non-chemical strategies has increased over the last decade.

Fungal pathogens commonly infect insects [8] and there has been extensive research on numerous species of Deuteromycete fungi (e.g. Culicinomyces spp., Beauveria spp., Metarhizium spp. and Tolypocladium spp.) for use as biological pest control agents in agriculture [9–13]. Although such fungi appear to have limited impact on mosquito populations under natural conditions [8, 14], there is increasing evidence supporting the potential use of isolates of Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae for control of adult mosquito vectors [15–25].

Given the emerging problems of insecticide resistance, one of the key requirements for any new (bio) pesticide product for mosquito control is to have limited cross-resistance with existing chemical insecticides [26, 27]. Clearly, if resistance to widely used insecticides, such as permethrin and DDT, confers resistance to fungal pathogens then potential novel biopesticide products will have limited utility either as replacements for insecticides, or in integrated strategies for insecticide resistance management [18]. The likelihood of cross-resistance occurring in mosquitoes, however, appears to be remote and in fact it would seem that in certain instances infection with fungi counteracts resistance that is based on metabolic mechanisms, at least in laboratory colonies [25]. One aim of the current study, therefore, was to compare the virulence of a candidate strain of the entomopathogenic fungus B. bassiana against insecticide-resistant and susceptible Anopheles arabiensis laboratory colonies, as well as wild collected adult mosquitoes to determine fungal susceptibility.

Additionally, because fungal pathogens are living organisms, the rate at which they penetrate and grow within an infected host is determined by temperature. Accordingly, the efficacy of certain fungal biopesticide products in agriculture has been shown to be strongly influenced by environmental temperature, in some cases further mediated by thermal behaviour of the target insect [28–31]. The effects can be such that under certain conditions, speed of kill is rapid and overall control very good, while under other conditions, speed of kill is very slow and control inadequate [30, 31]. In a recent study, Blanford et al[22] demonstrated that Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes infected with B. bassiana or M. anisopliae did not exhibit any change in thermal behaviour that might affect speed of kill. Nonetheless, temperature remains an important environmental factor likely to affect fungal germination and growth rate inside mosquito hosts. With respect to malaria control, a critical factor is how the speed of kill (virulence) varies relative to the extrinsic incubation period (EIP) of the malaria parasite; if mortality is faster than the rate of parasite development then impact on transmission will be greater than if mortality is slower than the parasite rate of development [21]. Importantly, both the EIP and pathogen growth vary with temperature [31, 32]. The second aim of the current study, therefore, was to explore the effect of temperature on virulence of B. bassiana against insecticide susceptible and resistant An. arabiensis. The daily average temperature measured inside traditional African houses between seasons in western Kenya is 23 ± 1.8°C [33–35]. Therefore, the impact of B. bassiana was assessed nder temperature regimes 2°C lower and higher than this average to capture the range of mean temperatures likely experienced in indoor resting sites.

Methods

Wild mosquito collection

Mosquitoes were collected inside traditional houses in Karonga (9° 48'51.04" S, 33° 52'.97" E), northern Malawi, using a mouth aspirator. They were placed into small polystyrene cups covered with gauze netting and later identified morphologically using the taxonomic keys of Gillies and Coetzee [36]. Only female mosquitoes identified as members of the Anopheles gambiae complex were retained. A cohort of these mosquitoes was maintained on a 10% sucrose solution soaked in cotton pads for a few hours after which they were subjected to insecticide susceptibility tests. Another cohort of female mosquitoes was blood-fed for oviposition. These mosquitoes were also maintained on a sucrose solution before and during transportation to the laboratory for colony rearing and fungal susceptibility tests.

Mosquito rearing

Colonies of An. arabiensis housed at the Vector Control Reference Unit of the National Institute for Communicable Diseases, Johannesburg, South Africa, were maintained under standard insectary conditions of 25 ± 2°C, 80% ± 10% relative humidity (RH) and a 12:12 hour day/night cycle with 45 minutes dusk/dawn transition between photo-periods. Field collected mosquitoes were reared under the same conditions in order to obtain F1 progeny to be used for fungal infection experiments. Female mosquitoes were offered blood meals two or three times whereafter each gravid female mosquito was placed in a glass vial lined with a moistened filter paper to allow for egg laying. Individual egg batches were transferred into plastic bowls (250 ml) half filled with distilled water. F1 larvae were reared in the same bowl until they pupated. All larvae were fed twice daily with a mixture of brewer's yeast and finely ground dog biscuits. Pupae were transferred daily into plastic vials (50 ml) half filled with distilled water and covered with gauze netting. Emerged F1 adult mosquitoes were collected using an aspirator and kept in small cups (180 ml) covered with gauze netting or in small plastic cages (2.5 litres). F1 adult progeny were maintained on a 10% sucrose solution soaked in cotton pads for 2-3 days before being subjected to fungal susceptibility tests.

Species identification

The Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) method [37] was used to test the species integrity of selected laboratory-reared An. arabiensis colonies as well as to identify wild-caught material morphologically identified as An. gambiae complex. Selected laboratory colonies included SENN and SENN-DDT originating from Sudan, and MBN and MBN-DDT originating from Kwazulu/Natal, South Africa. SENN-DDT and MBN-DDT were selected for resistance to DDT from their respective parent colonies.

Insecticide susceptibility tests

Newly emerged adult mosquitoes from each An. arabiensis colony were exposed to discriminating dosages of representative insecticides from all insecticide classes recommended by WHO for malaria vector control (Table 1). The standard insecticide susceptibility assays and test kits were used [38]. Samples of 25 non blood-fed mosquitoes per cylinder were exposed to insecticide-treated papers for one hour. After exposure, mosquitoes were transferred to clean holding tubes and provided with cotton pads soaked in a 10% sucrose solution. Knock-down was recorded after 1 h exposure and final mortality was recorded 24 h post-exposure. Each test was duplicated for fully insecticide susceptible colonies and triplicated for insecticide resistant colonies. Tests to determine the insecticide susceptibility status of field-collected mosquitoes were limited to DDT (organochlorine) and dieldrin (cyclodiene) because of sample size limitations. Insecticide susceptibility status was determined according to WHO criteria, whereby colonies were considered resistant when more than 20% of individuals survived the diagnostic dose 24 h post-exposure. A final mortality of 98-100% indicates full susceptibility whilst mortality between 80-97% suggests the possibility of resistance that needs further confirmation [38].

Fungal susceptibility tests

Fungal infection experiments were performed under two different temperature regimes: 21 ± 1°C and 25 ± 2°C, both under 70% ± 15% relative humidity. Infection was carried out using 'fungal suspensors' prepared according to the method described by Scholte et al[15]; this approach is not meant to mimic potential operational delivery of spores but provides a reliable infection method for controlled laboratory-based assays. For each trial three suspensors measuring 6.5 cm in height and 2.5 cm in diameter were lined on the inside with a cylinder of filter paper which also served to hold a plastic vial half filled with a 10% sucrose solution for moistening the filter paper. The sugar solution served as a mosquito attractant to each suspensor. Approximately 100 mg of B. bassiana (isolate IMI 391510) conidial powder was weighed and dusted onto treatment suspensors using a small paintbrush. Treated suspensors and an equal number of untreated, control suspensors were placed individually into small cages (2.5 litres). Cohorts of 25-35 sugar-fed 2-3 day old adult female mosquitoes from each colony were exposed to either treated or untreated suspensors for 24 h. A minimum of three trials was conducted per colony, each consisting of three treatment replicates and three controls. After the 24 h exposure mosquitoes were transferred into clean holding cages and fed on a 10% sucrose solution during the monitoring period.

Mortality in treatment and control samples was recorded daily up until the death of all fungus-infected mosquitoes. All dead mosquitoes were removed from their respective cages using dissecting forceps. Each cadaver was dipped in 70% ethanol in order to eliminate saprophytic fungi from their cuticles. They were then placed in Petri dishes lined with moistened filter paper and sealed with parafilm to maintain high humidity for fungal sporulation. Petri dishes were incubated at 25 ± 2°C for a period of 3-5 days after which cadavers were screened for external fungal growth under a compound microscope. Cadavers with visible fungal growth on their body surface were considered to have died as a result of fungal infection. Final fungal infection proportion was recorded per sample.

Data recording and analysis

Mosquito survival was recorded daily. Cox' regression analysis [39] using SPSS 15.0 software was used to compare survival between treatments and controls. Comparisons of mortality rates were used to assess differences in the effect of fungus infection on survival between insecticide susceptible and resistant colonies, laboratory-reared and wild caught An. arabiensis as well as between the two temperature regimes. For each factor, i.e. insecticide susceptibility status, colony and temperature, two-way interactions (of the factor with fungus treatment) were included in the Cox Regression model to test if the effect of fungal infection on mosquito survival was significantly influenced by the factor.

Results

Species identification and confirmation

A sample of 386 An. gambiae complex mosquitoes was collected from the field in Malawi. They were all identified as An. arabiensis by PCR. All samples drawn from the laboratory-reared colonies were confirmed to be as An. arabiensis.

Insecticide susceptibility tests

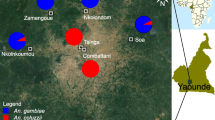

The insecticide susceptibility status of the laboratory An. arabiensis colonies and the wild-caught sample is shown in Figure 1. There was no evidence of insecticide resistance in MBN and field-collected mosquitoes, although the latter were only exposed to 4% DDT and 4% dieldrin because of limited numbers available for exposure assays. There was clear evidence of resistance to 0.75% permethrin in the baseline colony SENN. The SENN-DDT and MBN-DDT selected colonies showed measurable resistance to DDT as expected, as well as resistance to one or more insecticides from each of the other classes (pyrethroids, carbamates and organophosphates).

Insecticide susceptibility status of four laboratory strains and one field strain of Anopheles arabiensis. Data show the average mosquito mortality (%) after a 1 hour exposure to insecticide treated papers, recorded 24 hours post-exposure, of two replicates of 25 mosquitoes for the susceptible groups and three replicates for the resistant groups.

Fungal susceptibility tests

Daily survival of the field-collected mosquitoes after fungus exposure is shown in Figure 2. Exposure to dry B. bassiana spores resulted in significant reductions in longevity of the wild An. arabiensis mosquitoes (P < 0.05, HR > 1) relative to their respective controls. Comparisons of survival following fungal exposure between wild-caught and baseline laboratory-reared An. arabiensis (MBN and SENN, Figure 3) did not reveal any significant difference in susceptibility to fungal infection (P < 0.05, HR > 1).

Daily cumulative proportional survival of F1 offspring of An. arabiensis collected in Karonga, Malawi. Data show the average ± SE survival of nine replicate groups of 25-35 mosquitoes infected with B. bassiana (open symbols) and uninfected control groups (closed symbols) kept at 21 ± 1°C (red) or 25 ± 2°C (blue).

Daily cumulative proportional mosquito survival of insecticide-susceptible (blue) and insecticide-resistant (red) An. arabiensis laboratory colonies originating from Sudan (SENN) or Kwazulu/Natal (MBN). Data show the average ± SE survival of nine replicate groups of 25-35 mosquitoes infected with B. bassiana (open symbols) and uninfected control groups (closed symbols) kept at 21 ± 1°C (top) or 25 ± 2°C (bottom).

Survival curves of the insecticide resistant and susceptible laboratory colonies are shown in Figure 3. Exposure to B. bassiana spores resulted in significant reductions in longevity in all mosquito colonies (P < 0.05, HR > 1) relative to their respective controls, regardless of their insecticide susceptibility levels and temperature regimes. Cox-regression analysis revealed no significant differences in fungus-infected mortality rates between the insecticide-resistant and baseline colonies. Interaction analyses indicated no significant influence of insecticide susceptibility status on fungus-induced mortality rates at both tested temperatures (HR = 0.769; P = 0.13 and HR = 1.456; P = 0.61 for MBN vs MBN-DDT at 21°C and 25°C respectively and HR = 1.03; P = 0.86 and HR = 0.576; P = 0.27 for SENN vs SENN-DDT respectively at 21°C and 25°C). Even where fungus mortality rates appeared slower in insecticide resistant lines, as in MBN-DDT (Figure 3), this is not because of increased fungal resistance but because the respective untreated control lines also survived better. Therefore, fungal susceptibility is not affected by resistance to insecticides. Fungus-induced mortality rates were relatively rapid at 25°C, with 100% mortality taking 10-12 days post-fungus exposure in the baseline colonies (MBN and SENN) and field-collected mosquitoes, and 18-21 days in the DDT-selected colonies (MBN-DDT and SENN-DDT). At 21°C, equivalent mortalities took 20-28 days and 27-30 days, respectively (Figure 3). The differences in mortality rate were mirrored in the sporulation data, with > 90% sporulation of cadavers in the 25°C regime compared with just over 70% at 21°C. However, not all infected mosquito cadavers show fungal sporulation after death because some mosquitoes may be killed by fungal toxins or secondary infections, rather than primary fungal growth and invasion of organs that tends to facilitate sporulation of the cadaver. As observed from the hazard ratio values in Table 2, the fungus had a stronger effect at higher temperatures than at low temperatures. Cox-regression interaction analyses revealed a significant difference (P = 0.045) in the effect of the fungus on survival between the two temperature regimes. The hazard ratios (risk of death) were greater at the higher temperatures of 25 ± 2°C than at the lower temperatures of 21 ± 1°C (Table 2), suggesting that the probability of a mosquito dying soon after infection was greater at higher temperatures than at lower temperatures. Thus, quantitative differences were detected between the two exposure temperatures in all colonies tested (Figures 2 and 3).

Discussion

Mosquitoes caught resting indoors north of Karonga on Lake Malawi consisted solely of An. arabiensis. Conditions during the collection period were dry and hot, favouring a preponderance of this member of the An. gambiae complex, which is generally more tolerant of such conditions [36, 40–42].

There are clear indications of insecticide resistance to all insecticides and their respective classes tested in one or more of the An. arabiensis samples used. The controlling mechanisms of these resistance phenotypes are likely to involve target site mutations such as kdr as well as metabolic detoxification [2, 7, 43–47]. Resistance to insecticides in major malaria vector species, coupled to the limited number of insecticides available for use in public health programmes, highlights the need to evaluate the potential efficacy of entomopathogens.

All laboratory-reared and wild-caught An. arabiensis lines were susceptible to B. bassiana. Though quantitative differences were detected between the two exposure temperatures in all colonies tested, Beauveria significantly reduced mosquito longevity at both temperature regimes with no evidence for enhanced resistance to fungal infection due to insecticide resistance. Where mortality rate was apparently slowed due to DDT resistance, this effect was due to enhanced overall survival in the selected lines relative to the baseline colonies, rather than any significant reduction in susceptibility to fungus per se. Why these resistant mosquitoes survived better than controls in the absence of insecticide exposure is unclear. The DDT resistance in these lines is linked to higher levels of expression of glutathione S-transferases (GST) and esterases [47]. Conceivably these generic detoxifying enzymes could enhance survival in the laboratory environment, although trade-offs against other traits and fitness measures might be expected in other environments [48–50].

Beauveria killed mosquitoes significantly quicker at 25°C than at 21°C. This result is consistent with the known temperature-growth profile for this isolate, which indicates a temperature optimum of around 26°C (unpublished data). As suggested previously, to interpret the possible significance of this effect it is important to consider not just absolute speed of kill, but speed of kill relative to the length of the EIP. According to the classic day-degree model of Detinova [51], the EIP of P. falciparum is 12.3 days at 25°C and 22.2 days at 21°C. Thus, if mosquitoes became infected with malaria and fungus more or less simultaneously (as would happen if mosquitoes contacted fungus on a treated surface following an infectious blood feed), no mosquitoes would have survived long enough to transmit malaria in any of the colonies held at 25°C. At 21°C, fungal infection of the recently derived Malawi colony would have reduced the percentage of mosquitoes potentially able to transmit malaria (i.e. comparing percent alive at day 22 in control and treated populations) from 64% to 4%, representing a 92% reduction. In the two longer-lived DDT resistant colonies, the equivalent figures are 64% to 17% and 55% to 20%, representing reductions in transmission potential of approximately 70%. Thus, although still contributing to substantial reductions in transmission potential, the fungus appears to work less well at 21°C.

Fully extrapolating these results to potential impact in the field is difficult as mortality schedules could potentially differ markedly between lab and field environments for a variety of reasons. Moreover, the current study considers only one dose and it is likely that higher doses could help compensate for the apparent thermal constraint at 21°C. Studies exploring higher fungal doses and different bioassay exposure techniques have shown the potential for much more rapid mosquito mortality than observed in the current study [e.g. [15, 52]], and studies with other insect hosts indicate 'dose x temperature' interactions whereby effects of lower doses are magnified at sub-optimal temperatures [53]. Of course, selection of a different fungal isolate that is less temperature sensitive, or combining isolates with different temperature optima could overcome the constraint completely [18]. Furthermore, the growth rate of the malaria parasite slows exponentially as temperatures decrease further towards 18°C [51], whereas the decline in fungal growth rate appears more linear over this range (unpubl. data) so it is likely that at slightly cooler temperatures still, the relative efficacy of the current isolate would recover. In addition, sub-lethal effects of infection such as impact on malaria parasite development [16, 18] and reduced feeding propensity [54, 55] can reduce mosquito vectorial capacity irrespective of speed of kill [21]. Nonetheless, with potential for considerable variation in both mean conditions and diurnal temperature ranges across different transmission environments [56], understanding the effects of temperature on biopesticide performance is an important area for further research [see also [57]].

Overall, the results of the current study demonstrate that relative susceptibility of Anopheles arabiensis to a candidate fungal biopesticide strain is not affected by resistance to insecticides (see also [25]), that wild-caught mosquitoes are equally susceptible to fungal infection and that although there was temperature-dependent variation in fungal virulence, fungal infection led to substantial reductions in malaria transmission potential in conditions typical of local African houses (at least in western Kenya). These empirical data add support to recent modelling studies suggesting that as long as coverage is high (a goal of most conventional vector control operations), slow acting biopesticides can deliver substantial reductions in malaria transmission across a range of conditions [21, 23, 58, 59]. Of particular relevance here is the study of Koella et al[58], who demonstrated that the level of control (whether biological or conventional) necessary to reduce or even prevent malaria transmission depends on the background transmission intensity. In areas of low to moderate transmission, <50% reduction could provide substantial control, whereas in areas of very high transmission, even 90% reduction might not be sufficient to deliver any benefit due to the strongly saturating relationship between malaria prevalence and transmission [58, 60]. Thus the significance of the temperature-dependence in biopesticide performance needs to be considered in relation to the local epidemiology context.

Additionally, the efficacy and impact of a biopesticide will depend on ultimate use strategy. For example, in a recent theoretical study, Hancock [59] demonstrated that under conditions of intense transmission, high single coverage of either ITNs or IRS with a fungal biopesticide might not substantially reduce malaria prevalence in the human population, whereas intermediate coverage of both interventions simultaneously could. This conclusion, together with the empirical data demonstrating that resistance to insecticides does not confer resistance to fungi, highlights the potential for development of novel integrated control strategies combining insecticide and biopesticide interventions. Understanding such interactions, together with the local environmental context, are important areas for future research to define possible limits to biopesticide performance and identify isolates, doses and potential delivery systems to optimise control strategies across time and space.

References

World Health Organization: World malaria report. 2008, Geneva, Switzerland: WHO

Hemingway J, Ranson H: Insecticide resistance in insect vectors of human disease. Ann Rev Entomol. 2000, 45: 371-391. 10.1146/annurev.ento.45.1.371.

Hargreaves K, Koekemoer LL, Brooke BD, Hunt RH, Mthembu J, Coetzee M: Anopheles funestus is resistant to pyrethroid insecticides in South Africa. Med Vet Entomol. 2000, 14: 181-189. 10.1046/j.1365-2915.2000.00234.x.

Coetzee M, Horne DWK, Brooke BD, Hunt RH: DDT, dieldrin and pyrethroid resistance in African malaria vector mosquitoes: an historical review and implications for future malaria control in southern Africa. South Afr J Sci. 1999, 95: 215-218.

Etang J, Manga L, Chandre F, Guillet P, Fondjo E, Mimpfoundi R, Toto JC, Fontenille D: Insecticide susceptibility status of Anopheles gambiae s.l . (Diptera: Culicidae) in the Republic of Cameroon. J Med Entomol. 2003, 40: 491-497. 10.1603/0022-2585-40.4.491.

Coetzee M, Van Wyk P, Booman M, Koekemoer LL, Hunt RH: Insecticide resistance in malaria vector mosquitoes in a gold mining town in Ghana and implications for malaria control. Bull Soc Path Exot. 2006, 99: 400-403.

Abdalla H, Matambo TS, Koekemoer LL, Mnzava AP, Hunt RH, Coetzee M: Insecticide susceptibility and vector status of natural populations of Anopheles arabiensis from Sudan. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007, 102: 263-271. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.10.008.

Scholte E-J, Knols BGJ, Samson RA, Takken W: Entomopathogenic fungi for mosquito control: A review. J Insect Sci. 2004, 4: 19-

Ferron P: Biological control of insect pests by entomopathogenic fungi. Ann Rev Entomol. 1978, 23: 409-422. 10.1146/annurev.en.23.010178.002205.

Khan HK, Jayaraj S, Gopalan M: Muscardine fungi for the biological control of agroforestry termite Odontotermes obesus . Insect Sci Appl. 1993, 14: 529-535.

Milner RJ, Prior C: Susceptibility of Australian plague locust, Chortoicetes terminifera, and wingless grasshopper, Phaulacridium vittatum, to the fungi Metarhizium spp . Biol Control. 1994, 4: 132-137. 10.1006/bcon.1994.1021.

Thomas MB, Blanford S, Lomer CJ: Reduction of feeding by the variegated grasshopper, Zonocerus variegates, following infection by the fungal pathogen, Metarhizium flavoviride . Biocont Sci Technol. 1997, 7: 327-334. 10.1080/09583159730730.

Shah PA, Pell JK: Entomopathogenic fungi as biological control agents. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2003, 61: 413-423.

Clark TB, Kellen W, Fukuda T, Lindegren JE: Field and laboratory studies on the pathogenicity of the fungus Beauveria bassiana to three genera of mosquitoes. J Invertebr Pathol. 1968, 11: 1-7. 10.1016/0022-2011(68)90047-5.

Scholte E-J, Njiru BN, Smallegang RC, Takken W, Knols BGJ: Infection of malaria (Anopheles gambiae s.s.) and filariasis (Culex quinquefasciatus) vectors with the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae . Malar J. 2003, 2: 29-10.1186/1475-2875-2-29.

Blanford S, Chan BHK, Jenkins N, Sim D, Turner RJ, Read AF, Thomas MB: Fungal pathogen reduces potential for malaria transmission. Science. 2005, 308: 1638-1641. 10.1126/science.1108423.

Scholte E-J, Ng'habi K, Kihonda J, Takken W, Paaijmans K, Abdulla S, Killeen GF, Knols BGJ: An entomopathogenic fungus for control of adult African malaria mosquitoes. Science. 2005, 308: 1641-1643. 10.1126/science.1108639.

Thomas M, Read AF: Can fungal biopesticides control malaria?. Nat Rev. 2007, 5: 377-383. 10.1038/nrmicro1638.

Farenhorst M, Farina D, Scholte E-J, Takken W, Hunt RH, Coetzee M, Knols BGJ: African water storage pots for the delivery of the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae to the malaria vectors Anopheles gambiae s.s. and Anopheles funestus . Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008, 78: 910-916.

Darbro J, Thomas MB: Spore persistence and likely aeroallergenicity of entomopathogenic fungi used for mosquito control. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009, 80: 992-997.

Hancock PA, Thomas MB, Godfray HCJ: An age-structured model to evaluate the potential of novel malaria-control interventions: a case study of fungal biopesticide sprays. Proc R Soc London. 2009, 276: 71-80. 10.1098/rspb.2008.0689.

Blanford S, Read A, Thomas MB: Thermal behaviour of Anopheles stephensi in response to infection with malaria and fungal entomopathogens. Malar J. 2009, 8: 72-10.1186/1475-2875-8-72.

Read AF, Lynch PA, Thomas MB: How to make evolution-proof insecticides for malaria control. PLoS Biol. 2009, 7: 4-10.1371/journal.pbio.1000058.

Achonduh OA, Tondje PR: First report of pathogenicity of Beauveria bassiana RBL 1034 to the malaria vector, Anopheles gambiae s.l. (Diptera; Culicidae) in Cameroon. Afr J Biotechnol. 2008, 7: 931-935.

Farenhorst M, Mouatcho JC, Kikankie CK, Brooke BD, Hunt RH, Thomas MB, Koekemoer LL, Knols BGJ, Coetzee M: Fungal infection counters insecticide resistance in African malaria mosquitoes. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2009, 106: 17443-17447. 10.1073/pnas.0908530106.

Nauen R: Insecticide resistance in disease vectors of public health importance. Pest Manag Sci. 2007, 63: 628-633. 10.1002/ps.1406.

Kelly-Hope L, Ranson H, Hemingway J: Lessons from the past: managing insecticide resistance in malaria control and eradication programmes. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008, 8: 387-398. 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70045-8.

Watson DW, Mullens BA, Petersen JJ: Behavioural response of Musca domestica (Diptera: Muscidae) to infection by Entomophthora muscae (Zygomycetes: Entomophtorales). J Invertebr Pathol. 1993, 61: 10-16. 10.1006/jipa.1993.1003.

Inglis DG, Johnson DL, Goettel MS: Effects of temperature and thermoregulation on mycosis by Beauveria bassiana in grasshoppers. Biol Control. 1996, 7: 131-139. 10.1006/bcon.1996.0076.

Klass JI, Blanford S, Thomas MB: Development of a model for evaluating the effects of environmental temperature and thermal behaviour on biological control of locusts and grasshoppers using pathogens. Agr Forest Entomol. 2007, 9: 189-199. 10.1111/j.1461-9563.2007.00335.x.

Klass JI, Blanford S, Thomas MB: Use of geographic information systems to explore spatial variation in pathogen virulence and the implications for biological control of locusts and grasshoppers. Agr Forest Entomol. 2007, 9: 201-208. 10.1111/j.1461-9563.2007.00336.x.

Craig MH, Snow RW, Le Sueur D: A climate-based distribution model of malaria transmission in sub-Saharan Africa. Parasitol Today. 1999, 15: 105-111. 10.1016/S0169-4758(99)01396-4.

Knols BGJ, Njiru B, Mathenge EM, Mukabana WR, Beier JC, Killeen GF: MalariaSphere: a greenhouse-enclosed simulation of a natural Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae) ecosystem in western Kenya. Malar J. 2002, 1: 19-10.1186/1475-2875-1-19.

Okech BA, Gouagna LC, Killeen GF, Knols BGJ, Kabiru EW, Beier JC, Yan G, Githure JI: Influence of sugar availability and indoor microclimate on survival of Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae) under semifield conditions in western Kenya. J Med Entomol. 2003, 40: 657-663. 10.1603/0022-2585-40.5.657.

Okech BA, Gouagna LC, Knols BGJ, Kabiru EW, Killeen GF, Beier JC, Yan G, Githure JI: Influence of indoor microclimate and diet on survival of Anopheles gambiae s.s. (Diptera: Culicidae) in village house conditions in western Kenya. Int J Trop Insect Sci. 2004, 24: 207-212. 10.1079/IJT200427.

Gillies M, Coetzee M: A Supplement to the Anophelinae of Africa South of the Sahara. 1987, The South African Institute for Medical Research, Johannesburg

Scott JA, Brogdon WG, Collins FH: Identification of single specimens of the Anopheles gambiae complex by the polymerase chain reaction. Am J. 1993, 49: 520-529.

World Health Organization: Test procedures for insecticide resistance monitoring in malaria vectors, Bio efficacy and persistence of insecticides on treated surfaces. WHO/CDS/CPC/MAL/98.12, Geneva. 1998

Cox DR: Regression models and life tables. J R Stat Soc B. 1972, 34: 187-220.

Gillies M, De Meillon B: The Anophelinae of Africa South of the Sahara (Ethiopian zoogeographical region). 1968, The South African Institute for Medical Research, Johannesburg

Lindsay SW, Parson L, Thomas CJ: Mapping the ranges and relative abundance of the two principal African malaria vectors, Anopheles gambiae sensu stricto and An. arabiensis, using climate data. Proc Biol Sci. 1998, 265: 847-854. 10.1098/rspb.1998.0369.

Petrarca V, Nugud AD, Ahmed MA, Harid AM, DiDeco MA, Coluzzi M: Cytogenetics of the Anopheles gambiae complex in Sudan with special reference to An. arabiensis : relationships with East and West African populations. Med Vet Entomol. 2000, 14: 149-164. 10.1046/j.1365-2915.2000.00231.x.

Martinez-Torres D, Chandre F, Williamson MS, Darriet F, Serge JB, Devonshire AL, Guillet P, Pasteur N, Pauron D: Molecular characterisation of pyrethroid knockdown resistance (kdr) in the major malaria vector Anopheles gambiae s.s . Insect Mol Biol. 1998, 7: 179-184. 10.1046/j.1365-2583.1998.72062.x.

Ranson H, Jensen B, Vulule JM, Wang X, Hemingway J, Collins FH: Identification of a point mutation in the voltage-gated sodium channel gene of Kenyan Anopheles gambiae associated with resistance to DDT and pyrethroids. Insect Mol Biol. 2000, 9: 491-497. 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2000.00209.x.

Diabate A, Baldet T, Chandre F, Dabire R, Simard F, Ouedraogo JB, Guillet P, Hougard JM: The role of agricultural use of insecticides in resistance to pyrethroids in Anopheles gambiae s.l . in Burkina Faso. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002, 67: 617-622.

Fanello C, Petrarca V, Della Torre A: The pyrethroid knock-down resistance gene in the Anopheles gambiae complex in Mali and further indication of incipient speciation within Anopheles gambiae s.s. Insect Mol Biol. 2003, 12: 241-245. 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2003.00407.x.

Matambo TS, Abdalla H, Brooke BD, Koekemoer LL, Mnzava A, Hunt RH, Coetzee M: Insecticide resistance in the malarial mosquito Anopheles arabiensis and association with the kdr mutation. Med Vet Entomol. 2006, 21: 97-102. 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2007.00671.x.

Agnew P, Berticat C, Bedhomme S, Sidobre C, Michalakis Y: Parasitism increases and decreases the costs of insecticide resistance in mosquitoes. Evol. 2004, 58: 579-586.

Tabashnik BE, Dennehy TJ, Carriere Y: Delayed resistance to transgenic cotton in pink bollworm. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005, 102: 15389-15393. 10.1073/pnas.0507857102.

Labbé P, Berticat C, Berthomieu A, Unal S, Bernard C, Weill M, Lenormand T: Forty years of erratic insecticide resistance evolution in the mosquito Culex pipiens . PloS Genetics. 2007, 3: 2190-2199. 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030205.

Detinova TS: Age-grouping methods in Diptera of medical importance. 1962, World Health Organization, Geneva

Farenhorst M, Knols BGJ: A novel method for standardized application of fungal spore coatings for mosquito exposure bioassays. Malar J. 2010, 9: 27-10.1186/1475-2875-9-27.

Arthurs SP, Thomas MB: Effect of dose, pre-mortem host incubation temperature and thermal behaviour on host mortality and mycosis and sporulation of Metarhizium anisopliae var acridum in Schistocerca gregaria . Biocontr Sci Technol. 2001, 11: 411-420. 10.1080/09583150120055826.

Scholte E-J, Knols BGJ, Takken W: Infection of the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae with the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae reduces blood feeding and fecundity. J Invertebr Pathol. 2006, 91: 43-49. 10.1016/j.jip.2005.10.006.

Ondiaka S, Bukhari T, Farenhorst M, Takken W, Knols BGJ: Effects of fungal infection on the host-seeking behaviour and fecundity of the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae Giles. Proc Netherlands Entomol Soc Meet. 2008, 19: 121-128.

Paaijmans KP, Read AF, Thomas MB: Understanding the link between malaria risk and climate. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2009, 106: 13844-13849. 10.1073/pnas.0903423106.

Blanford S, Read AF, Thomas MB: Thermal behaviour of Anopheles stephensi in response to infection with malaria and fungal entomopathogens. Malar J. 2009, 8: 71-10.1186/1475-2875-8-72.

Koella JC, Lynch PA, Thomas MB, Read AF: Towards evolution-proof malaria control with insecticides. Evol Appl. 2009, ISSN 1752-4571, doi:10.1111/j.1752-4571.2009.00072.x

Hancock PA: Combining fungal biopesticides and insecticide-treated bednets to enhance malaria control. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009, 5 (10): e1000525-10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000525.

Beier JC, Killeen GF, Githure JI: Short report: entomologic inoculation rates and Plasmodium falciparum malaria prevalence in Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999, 61: 109-113.

Acknowledgements

We thank Belinda Spillings for assistance with field collections and Joel Mouatcho for assistance with fungal experiments. This research was funded by an anonymous charity organisation. BGJK receives financial support from the Dutch Scientific Organisation (NWO, VIDI grant 864.03.004). MC is supported by the South African Research Chair Initiative of the Department of Science and Technology and the National Research Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

CKK carried out wild mosquito collections, species identification, insecticide and fungal susceptibility tests, data analysis, interpretation of results, and drafted the first version of the manuscript. BDB supervised all the laboratory experiments and contributed to the subsequent writing of the manuscript. BGJK obtained funding for the project and contributed to the editing of the manuscript. LLK supervised the insecticide susceptibility assays and species identification. MF assisted with the statistical analyses and contributed to the editing of the manuscript. RHH organised the field trip to Malawi and was involved in wild mosquito collections, identification and rearing. MBT provided fungal spores, was involved in methodology of fungal experiments and contributed to editing the manuscript. MC was involved in project design and contributed to the final editing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript prior to submission.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kikankie, C.K., Brooke, B.D., Knols, B.G. et al. The infectivity of the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana to insecticide-resistant and susceptible Anopheles arabiensis mosquitoes at two different temperatures. Malar J 9, 71 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-9-71

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-9-71