Abstract

Background

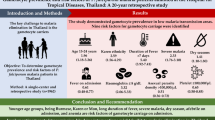

Amodiaquine is frequently used as a partner drug in combination therapy or in some setting as monotherapy, but little is known about its effects on gametocyte production and sex ratio and its potential influence on transmission in Africa. The effects of amodiaquine on sexual stage parasites and gametocyte sex ratio, and the factors associated with a male-biased sex ratio were evaluated in 612 children with uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria who were treated with amodiaquine during the period 2000 – 2006 in an endemic area.

Methods

Clinical, parasitological and laboratory parameters were evaluated before treatment and during follow-up for 28–42 days, and according to standard methods. Gametocyte sex ratio was defined as the proportion of peripheral gametocytes that are male.

Results

Clinical recovery from illness occurred in all children. Gametocytaemia was detected in 66 patients (11%) before treatment and in another 56 patients (9%) after treatment. Gametocyte densities were significantly higher by days 3–7 following treatment compared with pre-treatment (P < 0.0001). Overall, mean gametocyte sex ratio increased significantly during follow-up and over the study periods from 2000–2006 (P < 0.001 in both cases), but was female-biased at enrolment throughout the study periods. Absence of fever, a haematocrit < 25%, asexual parasitaemia > 20,000/μL, gametocytaemia < 18/μL, and enrolment in 2006 were associated with a male-biased sex ratio pre-treatment. Anaemia and high parasitaemia were independent predictors of gametocyte maleness 7 days post treatment.

Conclusion

Amodiaquine may significantly increase gametocyte carriage, density and sex ratio, and may potentially influence transmission. It is possible that anaemia could have contributed to the increased sex ratio. These findings may have implications for malaria control efforts in Africa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Amodiaquine, a Manic base related to chloroquine, is considered a safe drug for the treatment of acute, uncomplicated, Plasmodium falciparum malaria [1], and is increasingly used as partner drug for artemisinin [2–7] and non-artemisinin based [8–10] combination therapies. Studies have shown that antimalarials modify gametocyte carriage and influence malaria transmission [7, 11–14], suggesting careful consideration in the selection of partner drugs in combination therapies.

Despite similarity and superior efficacy to chloroquine, increasing use in Africa, and the suggestion that mutations conferring resistance to chloroquine may confer resistance to amodiaquine in Africa [15, 16], little is known of the effects of amodiaquine on gametocyte carriage and sex ratio, and its potential influence on transmission in African children. Such a study is necessary as it may potentially harness the efforts to control drug resistance and prolong the use of combination therapies in the community.

The aims of the present study were to: determine the effects of amodiaquine on asexual-stage parasites, gametocyte carriage and sex ratio; and evaluate the factors that influence the production of a male-biased sex ratio in children presenting with acute, symptomatic, uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria before and following treatment with amodiaquine in an endemic area.

Patients and methods

Patients

The study was conducted in children aged ≤ 12 years with acute, uncomplicated, P. falciparum malaria in Ibadan, a malaria endemic area in southwestern Nigeria [17]. Fully informed consent was obtained from the parents/guardians of each child. Inclusion criteria were: fever or history of fever in the 24–48 h preceding presentation, pure P. falciparum parasitaemia ≥ 2,000 asexual forms/μL, absence of other concomitant illness, no history of antimalarial use in the 2 weeks preceding presentation, and negative urine tests for antimalarial drugs (Dill-Glazko and lignin). Patients with severe malaria [18], severe malnutrition, serious underlying diseases (renal, cardiac, or hepatic), and known allergy to study drug were excluded from the study. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Ministry of Health, Ibadan, Nigeria.

Drug management

After clinical assessment, blood was obtained for haematocrit determination and for quantification of asexual and sexual parasitaemia. Patients were treated with 25–30 mg/kg of amodiaquine base (Camoquine®) given orally over 3 days. All patients waited for at least 3 h after to ensure the drug was not vomited. If it was, the patient was excluded form the study.

Oral paracetamol (acetaminophen) at 10–15 mg/kg 6–8 hourly was given for 12–24 h if body temperature was > 38°C. Patients were seen daily, at approximately the same time of the day for the first four days (days 0–3) and then daily on days 7, 14, 21, 28, 35 and 42 after treatment had begun. At each visit, patients were assessed clinically, and thick and thin blood smears were obtained for quantification of parasitaemia. The fever clearance time (FCT) was defined as the time taken for the body temperature to fall below 37.5°C and remain below this value for > 48 h.

Laboratory investigations

Asexual parasite and gametocyte counts were measured daily for the first four days (days 0–3) and thereafter on days 7, 14, 21, 28, 35 and 42. Quantification in Giemsa-stained thick blood films was undertaken against 500 leukocytes in the case of asexual parasitaemia, and against 1000 leukocytes in the case of gametocytes, and from this figure, the parasite density was calculated assuming a leukocyte count of 6,000/μL of blood. Parasite clearance time (PCT) was the time interval from the start of antimalarial treatment until the asexual parasite count fell below the detectable levels in a peripheral blood smear. Capillary blood, collected before and during follow-up, was used to measure packed cell volume (PCV). PCVs were measured using a microhaematocrit tube and microcentrifuge (Hawksley, Lancing, UK). Routine haematocrit was undertaken on days 0, 3, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35 and 42. Blood was spotted on filter papers on days 0, 1, 3, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35 and 42 and at the time of re-appearance of peripheral parasitaemia after its initial clearance for parasite genotyping. Molecular genotyping was carried out as previously described [16].

Determination of gametocyte sex ratio

Gametocyte sex determination was based on the following criteria [19, 20]: males (microgametocytes) are smaller than females (macrogametocytes), the nucleus is larger in males than females, the ends of the cells are rounder in males and angular in females, with Giemsa the cytoplasm stains purple in males and deep blue in females, and the granules of malaria pigment are centrally located females and more widely scattered in males. The sex ratio was defined as the proportion of gametocytes in peripheral blood that were male [21]. Gametocytes were sexed if the gametocyte density was ≥ 10/μL blood.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using version 6 of the Epi-Info software [22] and the statistical programme SPSS for Windows version 10.01 [23]. Variables considered in the analysis were related to the densities of P. falciparum gametocytes and trophozoites. Proportions were compared by calculating χ2 with Yates' correction or by Fisher exact or by Mantel Haenszel tests. Normally distributed, continuous data were compared by Student's t-tests and analysis of variance (ANOVA). Data not conforming to a normal distribution were compared by the Mann-Whitney U-tests and the Kruskal-Wallis tests (or by Wilcoxon ranked sum test). Kaplan-Meier plots are also presented to compare gametocyte carriage rates, and the duration of carriage of a male biased gametocyte sex ratio following treatment in those who were gametocytaemic at presentation. Differences in survival time were assessed by inspection of Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests. The relationship between gametocyte sex ratio and gametocyte or asexual parasite density was assessed by linear regression. A multiple logistic regression model was used to test the association between a male biased sex ratio, that is, sex ratio ≥ 0.5 (yes or no at presentation or during follow up) and factors that were significant at univariate analysis: presence of fever, haematocrit < 25%, asexual parasitaemia > 20,000/μL, and gametocytaemia < 18/μL. Because the study was conducted over a period of six and a half year, time in years since the commencement of the study was included as a covariate in the model for pre-treatment male-biased sex ratio. All tests of significance were two-tailed. P-values of ≤ 0.05 were taken to indicate significant differences. Data were (double)-entered serially using the patients' codes and were only analyzed at the end of the study.

Results

Baseline characteristics of patients at enrolment

Between September 2000 and December 2006, 615 children (297 males, 318 females) with P. falciparum malaria, aged between 0.5–12 years (mean ± standard deviation [SD] = 6.5 ± 3.2 years) were enrolled. Of these, 612 (294 males, 318 females) completed at least 28 days of follow up and were analyzed (Table 1). The characteristics of the children were similar during the study periods except for the geometric mean parasite density that was significantly higher in 2006 than in 2000 and 2004 (P < 0.0001) (Table 1).

Clinical responses

All children responded promptly to treatment, and none developed severe malaria. The overall mean (range) FCT was 1.1 (SEM 0.02) d, and was not significantly different between the years of enrolment (Table 1). None of the studied children had significant adverse effects as monitored by clinical symptoms, but overall, 46 children reported pruritus, which did not interfere with sleep.

Parasitological responses

The overall mean PCT (SEM) was 2.7 (0.005) d and was not significantly different during the study periods (Table 1). Recrudescent infections confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) occurred in 25 children: in 6, 8, and 11 children in 2000, 2004, and 2006, respectively. The characteristics of the recrudescent infections will be reported elsewhere.

Gametocytaemia

Gametocytes were detected in peripheral blood in 122 (20%) children (in 66 children before treatment and in 56 children after initiation of treatment) (Table 2). Gametocyte detection rates before, during and after treatment were similar during the study periods (Table 3). Gametocyte densities during the study periods are summarized in Table 3. Overall, gametocytaemia increased significantly by days 3–7 during follow up (P < 0.0001) but did not differ between the study periods.

Duration of gametocyte carriage in children with gametocytaemia at enrolment

The probability of a mosquito infectivity following a blood meal is related to gametocyte density and the duration of carriage by the host. Figure 1 is a Kaplan-Meier plot (survival curve) of the cumulative probability of remaining gametocyte free following treatment with amodiaquine during the study periods. The probabilities were similar during the periods of the study (Log rank statistic = 0.8, P = 0.23).

Temporal changes in gametocyte sex ratio

In 122 children who were gametocytaemic at presentation or during follow up, a total of 2,286, 2,197, 3,108, 4,676, 2,880, 618, 54 and 576 gametocytes were counted on days 0, 1, 2, 3, 7, 14, 21, and 28, respectively. Of these, 2,050, 1,986, 2,843, 4,518, 2,699, 600, 54, and 440 gametocytes could be sexed on days 0, 1, 2, 3, 7, 14, 21, and 28, respectively. The corresponding number of patients in whom the gametocytes were counted was 66, 49, 47, 70, 50, 29, 5, and 4, respectively.

Following treatment with amodiaquine, gametocyte sex ratio increased significantly over the course of the infection. (Figure 2 and Table 4): 7.6% of the gametocytes were male at day 0, 25% at day 3, and 29% at day 7 (X2 = 15.2, P = 0.0005). Gametocyte sex ratio at enrolment increased significantly during the study periods: the ratio was 0.4% in 2000, 4.8% in 2004, and 20% in 2006 (P < 0.0001), although it was still largely female-biased (Table 4). The variations in haematocrit, density of gametocyte and gametocyte sex ratio are shown in Figure 2. During the first week of follow up, gametocyte sex ratio increased as the packed cell volume decreased and the gametocyte density increased, suggesting that the latter may have been a direct contribution of the effect of amodiaquine on sex ratio, since, in general, low but not relatively high gametocytaemia is associated with male-biased sex ratio.

The possibility that gametocyte infectivity may be related to the duration of carriage of a less female biased sex ratio was examined. Figure 3 is a Kaplan-Meier plot of the cumulative probability of remaining a less female-biased sex ratio free following treatment with amodiaquine during the study periods. The probabilities were similar during the periods of the study (Log rank statistic = 2, P = 0.37).

Relationship between gametocyte sex ratio and gametocytaemia or asexual parasitaemia

The percentage of male gametocytes was negatively correlated with gametocyte density but not with asexual parasite density (Spearman's r = -0.46, P < 0.0001 and r = 0.009, P = 0.94, respectively with n = 66 in both cases.

Risk factors associated with a male-biased gametocyte sex ratio

The pre-treatment factors associated with a male-biased sex ratio are shown in Table 5. Age, gender or duration of illness before presentation appeared not to be associated with a male-biased sex ratio at enrolment. Absence of fever, a haematocrit < 25%, asexual parasitaemia > 20,000/μL, gametocytaemia < 18/μL, and enrolment in 2006 were significantly associated with a male-biased sex ratio at enrolment.

Following treatment, a haematocrit < 25% on days 0 and 7 and a parasitaemia greater > 20,000/μL of blood were independent predictors of a male biased sex ratio 7 days post initiation of treatment with amodiaquine (Table 6).

Discussion

The study showed continuing efficacy of amodiaquine against asexual parasites, relative lack of gametocytocidal effects, and peak gametocyte carriage occurring 3–7 days after treatment commenced. The last finding is in contradistinction to that following treatment with artemisinin derivatives or artemisinin-based combination therapy where peak gametocyte carriage is seen pre-treatment in children from this endemic area [7, 10, 24].

The average sex ratio of 0.076, is considerably lower than those reported from Senegal (0.346) [25] or Cameroon (0.22) [20]. Sex ratio increased over the relatively long period but the causes are unclear. Exposure of these children to sex ratio modifying influences, including antimalarial drugs [13, 26] may have been contributory. Sex ratio may be positively correlated with gametocyte density in animal infections [21, 27] but in the present study was significantly negatively correlated with gametocytaemia – a finding similar to that from Senegal [25].

Although significant variations in sex ratio may occur in natural populations [28, 29], a consistent finding during the entire period of the study was a significant shift in sex ratio towards maleness by day 7 of initiation of treatment. Indeed by this time, 29% of gametocytes were male. It would appear anaemia was an important contributor to gametocyte maleness and had resolved in many children by day 7 (Figure 3). However, overall, the absence of low gametocytaemia, which was expected to enhance gametocyte maleness as a form of fertility insurance [30], and the significantly increased gametocytaemia on day 7 (a possible effect of amodiaquine) suggest that by some as yet unknown way, amodiaquine may encourage the development of a less female-biased gametocyte sex ratio. A possible explanation is that amodiaquine or its metabolite could exert different effects on male and female gametocytes particularly if the gametocytes are exposed to the metabolite for a long time. Perhaps by an effect on sex-specific half-lives as has been previously reported for pyrimethamine-sulfadoxine [13] but it is yet to be investigated. Alternatively sequestered gametocytes with a less female biased sex ratio could have been released during this period. An interesting finding was the year to year variation in sex ratio. The reasons for this are unclear but may not be unrelated to environmental and other cues resulting in adaptive changes by the parasites.

Robert and others [25] found that in a population of symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals, anaemia and a wave of gametocytes were associated with significant effects on sex ratio. In the present data set, five factors were associated with increased risk of a less female biased sex ratio at enrolment: absence of fever, anaemia, asexual parasitaemia > 20,000/μL, low gametocytaemia and enrolment in the year 2006. The differences in the risk factors between the present study and that of Robert et al [25] clearly are due to differences in design. However, that anaemia is associated with a less female biased sex ratio may work in concert with other factors to promote the male biased sex ratio often observed following chemotherapy of the disease.

In lizard malaria parasite infections, high levels of parasitaemia are associated with a less female-biased sex ratio [21]. In the cohorts of children, high levels of parasitaemia, which are common in young children in this endemic area, were also found to be associated with a male-biased sex ratio. This was not unexpected – high levels of parasitaemia are associated with low gametocytaemia [14] – a relatively reduced risk of gametocyte carriage and a factor that promotes gametocyte maleness as a form of fertility insurance [30]. In addition, in areas of intense transmission, such as ours, a less female biased sex ratio is favoured [31] primarily because of multiplicity of infections, on the average the number of infecting clones in the area is about 3–4 [32, 33].

Absence of fever is associated with increased risk of gametocyte carriage [12, 14, 34]. It is unclear why afebrile children should have an increased risk of male biased sex ratio, and we have no explanation for our finding. Anaemia before, during, and after treatment was an important predictor of a male biased sex ratio following treatment with amodiaquine. This was expected and it supports the suggestion that this factor may contribute to antimalarial-associated gametocyte maleness. If artemisinin derivatives, as has been proposed, selectively favour the emergence of a female-biased sex ratio [7], it would now be important to evaluate the predictors of male biased sex ratio in children treated with different antimalarial drugs.

There is a need to justify the sex ratio regarded as male biased in our study. Traditionally, sex ratio is assigned by microscopy that often overestimated the proportion of female gametocytes [35]. Therefore, regarding a sex ratio ≥ 0.5 as male biased clearly shows a significantly male biased ratio. Sex ratio can now be more accurately estimated by a recently developed reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction techniques [36].

A limitation of the present study is that only gametocytaemia ≥ 10/μl were sexed. A limitation on the predictors of less female biased sex ratio is the inability to evaluate other potential predictors such as treatment with other gametocyte sex ratio modifying drugs such as pyrimethamine-sulphadoxine, trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole [13, 25]. This will be examined in an ongoing study. However, the present results are strengthened by the use of a consistent protocol over the entire study period; the 6.5 year-long period allowed the factoring of time into the analysis and to gain some insight into the evolution of a less female biased gametocyte sex ratio in our area of study, in a manner similar to our observations on the evolution of drug resistance in our study area [37].

Conclusion

Amodiaquine may significantly increase gametocyte carriage, density and sex ratio in African children treated for falciparum malaria, and may potentially influence transmission. It is also possible that anaemia could have contributed to the less female biased sex ratio.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Olliaro O, Nevill C, Lebras J, Ringwald P, Mussano P, Garner P, Brasseur P: Systematic review of amodiaquine treatment in uncomplicated malaria. Lancet. 1996, 348: 1196-1201. 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)06217-4.

World Health Organization: Antimalarial drug combination therapy. Report of a WHO Technical Consultation. 2001,WHO/CDS/RBM/2001.35.Geneva:WHO,

Adjuik M, Agnamey P, Babiker A, Borrmann S, Brasseur P, Cisse M, Cobelens F, Diallo S, Faucher JF, Garner P, Gikunda S, Kremsner PG, Krishna S, Lell B, Loolpapit M, Matsiegui P-B, Missinou MA, Mwanza J, Ntoumi F, Olliaro P, Osimbo P, Rezbach P, Some E, Taylor WRJ: Amodiaquine-artesunate versus amodiaquine for uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in African children: a randomized, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2002, 359: 1365-1372. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08348-4.

Adjuik M, Babiker A, Garner P, Olliaro P, Taylor W, White N: Artesunate combinations for treatment of malaria: meta-analysis. Lancet. 2004, 363: 9-17. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15162-8.

Mokuolu OA, Okoro EO, Ayetoro SO, Adewara AA: Effect of artemisinin-based treatment policy on consumption pattern of antimalarials. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007, 76: 7-11.

Sirima SB, Gansane A: Artesunate-amodiaquine for the treatment of uncomplicated malaria. Exp Opin Invest Drugs. 2007, 16: 1079-1085. 10.1517/13543784.16.7.1079.

Sowunmi A, Balogun T, Gbotosho GO, Happi CT, Adedeji AA, Fehintola FA: Activities of amodiaquine, artesunate, and artesunate-amodiaquine against asexual- and sexual-stage parasites in falciparum malaria in children. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007, 51: 1694-1699. 10.1128/AAC.00077-07.

Schellenberg D, Kahigwa E, Drakeley C, Malende A, Wigayi J, Msokame C, Aponte JJ, Tanner M, Mshinda H, Menendez C, Alonso PL: The safety and efficacy of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine, amodiaquine and their combination in the treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002, 67: 17-23.

Gasasira AF, Dorsey G, Nzarubara B, Staedke SG, Nassali A, Rosenthal PJ, Kamya MR: Comparative efficacy of aminoquinoline-antifolate combinations for the treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Kampala, Uganda. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003, 68: 127-132.

Sowunmi A, Gbotosho GO, Happi CT, Adedeji AA, Fehintola FA, Folarin OA, Tambo E, Fateye BA: Therapeutic efficacy and effects on gametocyte carriage of artemether-lumefantrine and amodiaquine-sulfalene-pyrimethamine on gametocyte carriage in children with acute uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in southwest Nigeria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007, 77: 235-241.

Price RN, Nosten F, Luxemburger C, ter Kuile FO, Paiphun L, Chongsuphajasiddhi T, White NJ: Effects of artemisinin derivatives on malaria transmissibility. Lancet. 1996, 347: 1654-1658. 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)91488-9.

von Seidlein L, Drakeley C, Greenwood B, Walraven G, Targett G: Risk factors for gametocyte carriage in Gambian children. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001, 65: 523-526.

Sowunmi A, Fateye BA: Gametocyte sex ratios in children with asymptomatic, recrudescent, pyrimethamine-sulfadoxine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2003, 97: 671-682. 10.1179/000349803225002381.

Sowunmi A, Fateye BA, Adedeji AA, Fehintola FA, Happi TC: Risk factors for gametocyte carriage in uncomplicated falciparum malaria in children. Parasitology. 2004, 129: 255-262. 10.1017/S0031182004005669.

Ochong EO, Broek Van Den IVF, Keus K, Nzila A: Short report: Association between chloroquine and amodiaquine resistance and allelic variation in the Plasmodium falciparum multiple drug resistance 1 gene and the chloroquine resistance transporter gene in isolates from the Upper Nile in southern Sudan. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003, 69: 184-187.

Happi CT, Gbotosho GO, Folarin OA, Bolaji OM, Sowunmi A, Kyle DE, Milhous W, Wirth DF, Oduola AMJ: Association between mutations in Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter and P. falciparum multidrug resistance 1 genes and in vivo amodiaquine resistance in P. falciparum malaria-infected children in Nigeria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006, 75: 155-161.

Salako LA, Ajayi FO, Sowunmi A, Walker O: Malaria in Nigeria: a revisit. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1990, 84: 435-445.

World Health Organization: Severe falciparum malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000, 94 (Suppl 1): 1-90. 10.1016/S0035-9203(00)90300-6.

Carter R, Graves PM: Gametocytes. Malaria: Principles and Practice of Malariology. Edited by: Wernsdorfer WH, McGregor I. 1988, Edingburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1: 253-303.

Robert V, Read AF, Essong J, Chuinkam T, Mulder B, Verhave JP, Carnevale P: Effects of gametocyte sex ratio on infectivity of Plasmodium falciparum to Anopheles gambiae. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1996, 90: 621-624. 10.1016/S0035-9203(96)90408-3.

Pickering J, Read AF, Guerrero S, West SA: Sex ratio and virulence in two species of lizard malaria parasites. Evol Ecol Res. 2000, 2: 171-184.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Epi Info Version 6. A word processing data base and statistics program for public health on IBM-compatible microcomputers. 1994, Atlanta, GA

SPSS Inc: SPSS for Windows release 10.01 (standard version). 1999, Chicago, IL

Sowunmi A, Balogun T, Gbotosho GO, Happi CT, Adedeji AA, Bolaji OM, Fehintola FA, Folarin OA: Activities of artemether-lumefantrine and amodiaquine-sulfalene-pyrimethamine against sexual-stage parasites in falciparum malaria in children. Chemotherapy. 2008, 54: 201-208. 10.1159/000140463.

Robert V, Sokhna CS, Rogier C, Ariey F, Trape J-F: Sex ratio of Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes in inhabitants of Dielmo, Senegal. Parasitology. 2003, 127: 1-8. 10.1017/S0031182003003299.

Sowunmi A, Fateye BA, Adedeji AA, Fehintola FA, Bamgboye AE, Babalola CP, Happi TC, Gbotosho GO: Effects of antifolates-cotrimoxazole and pyrimethamine-sulfadoxine on gametocytes in children with acute, symptomatic, uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2005, 100: 451-455. 10.1590/S0074-02762005000400019.

Taylor LH, Walliker D, Read AF: Mixed-genotype infections of the rodent malaria Plasmodium chabaudi are more infectious to mosquitoes than single genotype infections. Parasitology. 1997, 115: 121-132. 10.1017/S0031182097001145.

Paul REL, Packer MJ, Walmsley M: Mating patterns in malaria parasite populations of Papua-New-Guinea. Science. 1995, 269: 1709-1711. 10.1126/science.7569897.

Schall JJ: Transmission success of the malaria parasite Plasmodium mexicanum into its vector: role of gametocyte density and sex ratio. Parasitology. 2000, 121: 575-580. 10.1017/S0031182000006818.

West SA, Smith TG, Nee S, Read AF: Fertility insurance and the sex ratios of malaria and related hemosporin blood parasites. J Parasitol. 2002, 88: 258-263.

Read AF, Anwar M, Shutler D, Nee S: Sex allocation and population structure in malaria and related parasitic protozoa. Proc R Soc Lond B. 1995, 260: 359-363. 10.1098/rspb.1995.0105.

Happi CT, Thomas SM, Gbotosho GO, Falade CO, Akinboye DO, Gerena L, Hudson T, Sowunmi A, Kyle DE, Milhous W, Wirth DF, Oduola AMJ: Point mutations in the pfcrt and pfmdr-1 genes of Plasmodium falciparum and clinical response to chloroquine, among malaria patients from Nigeria. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2003, 97: 439-451. 10.1179/000349803235002489.

Happi TC, Gbotosho GO, Sowunmi A, Falade CO, Akinboye DO, Gerena L, Kyle DE, Milhous W, Wirth DF, Oduola AMJ: Molecular analysis of Plasmodium falciparum recrudescent malaria infections in children treated with chloroquine in Nigeria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004, 70: 20-26.

Price R, Nosten F, Simpson JA, Luxemburger C, Paiphun L, ter Kuile FO, van Vugt M, Chongsuphajasiddhi T, White NJ: Risk factors for gametocyte carriage in uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999, 60: 1019-1023.

Reece SE, Duncan AB, West SA, Read AF: Sex ratios in the rodent malaria parasite, Plasmodium chabaudi. Parasitology. 2003, 127: 419-425. 10.1017/S0031182003004013.

Drew DR, Reece SE: Development of reverse-transcription PCR techniques to analyse the density and sex ratio of gametocytes in genetically diverse Plasmodium chabaudi infections. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2007, 156: 199-209. 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.08.004.

Sowunmi A, Fateye BA, Adedeji AA, Fehintola FA, Gbotosho GO, Happi TC, Tambo E, Oduola AMJ: Predictors of the failure of treatment with chloroquine in children with acute, uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria, in an area with high and increasing incidences of chloroquine resistance. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2005, 99 (6): 535-544. 10.1179/136485905X51382.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to A.A. Adedeji and B.A. Fateye for help with collation of data, and to our clinic staff especially Moji Amao and Adeola Alabi for assistance with running the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

AS led the design, conduct, data analysis and manuscript preparation. STB was involved in data analysis and manuscript preparation. GOG and CTH were involved in the design, conduct, and preparation of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Sowunmi, A., Balogun, S.T., Gbotosho, G.O. et al. Plasmodium falciparum gametocyte sex ratios in children with acute, symptomatic, uncomplicated infections treated with amodiaquine. Malar J 7, 169 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-7-169

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-7-169