Abstract

Background

Plasmodium falciparum is the predominant human malaria species in Mozambique and a lead cause of mortality among children and pregnant women nationwide. Sulphadoxine/pyrimethamine (S/P) is used as first line antimalarial treatment as a partner drug in combination with artesunate.

Methods

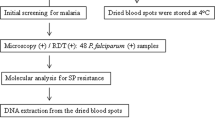

A total of 92 P. falciparum-infected blood samples, from children with uncomplicated malaria attending the Centro de Saude de Bagamoyo in the Province of Maputo-Mozambique, were screened for S/P resistance-conferring mutations in the pfdhfr and pfdhps genes using a nested mutation-specific polymerase chain reaction and restriction digestion (PCR-RFLP). The panel of genetic polymorphisms analysed included the pfdhfr 164L mutation, previously reported to be absent or rare in Africa.

Results

The frequency of the S/P resistance-associated pfdhfr triple mutants (51I/59R/108N) and of pfdhfr/pfdhps quintuple mutants (51I/59R/108N + 437G/540E) was 93% and 47%, respectively. However, no pfdhfr 164L mutants were detected.

Conclusion

The observation that a considerably high percentage of P. falciparum parasites contained S/P resistance-associated mutations raises concerns about the validity of this drug as first-choice treatment in Mozambique. On the other hand, no pfdhfr 164L mutant was disclosed, corroborating the view that that this allele is still rare in Africa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Mozambique is included in the top ten nations most affected by malaria, with Plasmodium falciparum being the predominant species. Malaria is of stable transmission and endemic in the entire country, making it the major cause of morbidity and mortality across all age groups, accounting for a third of all hospital deaths (USAID Mozambique Country Strategic Plan, FY 2004–2010). The choice of appropriate therapeutic policies that circumvent parasite chemoresistance has been one of the major challenges for malaria control nationwide. As the intensity of chloroquine resistance increased, the country implemented a change of first-line antimalarial treatment in 2002 to a combination of sulphadoxine/pyrimethamine (S/P) + amodiaquine. In 2004, this has been further altered to S/P + artesunate, in line with current WHO recommendations for the use of Artemisinin Combination Therapies (ACTs) [1].

Sulphadoxine and pyrimethamine (S/P) act as synergistic inhibitors of folate biosynthesis which, in malaria parasites, is an obligatory requirement for the production of nucleotides and hence DNA synthesis. Because both compounds act synergistically, any loss of efficiency in either component results in the reduction of the effectiveness of the combination as whole. In this context, the occurrence of certain molecular polymorphisms in the dihydrofolate reductase (pfdhfr) and dihydropteroate synthase (pfdhps) genes have been associated to in vivo S/P treatment outcome [2, 3]. Particularly in East Africa, the occurrence of the so-called pfdhfr/pfdhps quintuple mutant parasites (dhfr 51I/59R/108N + dhps 437G/540E) appears to be a good predictor of S/P treatment failure [4, 5].

Previous studies in Asia and South America have demonstrated that pfdhfr mutants harboring a change from I to L at position 164 in concert with 108N plus 51I and/or 59R mutations present high-level resistance to both pyrimethamine and cycloguanil [6, 7]. It has been suggested that this quadruple mutant has been selected through continued use of S/P in natural parasite populations [8–11]. Fortunately, P. falciparum I164L mutants have not consistently been detected in Africa so far [12]. Nevertheless, because S/P is safe and cost-effective, its use in Africa is growing either as first-line treatment alone or as a partner drug within a combination, increasing the likelihood of selection of I164L mutants. In face of such a scenario, routine molecular surveillance will be needed to detect the eventual emergence and propagation of this mutation.

The present work reports the prevalence of mutations in codons 51, 59, 108 and 164 of the pfdhfr gene and in codons 437 and 540 of the pfdhps gene among P. falciparum samples collected from symptomatic malaria-infected children from Maputo, Mozambique.

Methods

The study was conducted from July to October 2004, among symptomatic children attending in Bagamoyo Health Centre in Maputo City, Mozambique. One hundred children with uncomplicated malaria were enrolled. Inclusion criteria were i) monoinfection with P. falciparum, ii) no intake of antimalarial drugs during the last three weeks, iii) no signs of complications (patients who developed signs of complications were immediately transferred for adequate treatment and excluded from the study), iv) no history of allergic reactions to sulphonamides, and v) informed consent of a parent or guardian. The study was ethically reviewed and approved by the "Comité Nacional de Bioética para a Saúde", the local Ethics Committee. At each visit of the patients to the centre, thin and thick blood films were prepared from finger-pricked blood and 50 μl of blood were dotted on Whatman (Maidstone, United Kingdom) 3 MM filter paper and air-dried at room temperature. The presence of P. falciparum in the peripheral blood was determined by microscopical examination of thick blood films in slides stained with 5% Giemsa solution. Parasite quantification was done by calculating the percentage of P. falciparum-infected red blood cells upon examination of thin blood films prepared as above.

The preparation of parasite genomic DNA, nested mutation-specific PCR and detection of point mutations at pfdhfr (codons 51, 59, 108 and 164) and pfdhps (codons 437 and 540) was done using previously published protocols [13]. The frequency of mutant, wild-type and mixed genotypes was assessed for each individual polymorphic marker. To calculate the frequency of parasites carrying multiple mutations, mixed genotypes were excluded in order to maximize the probability that the observations reflected genuine haplotypes and not a fictitious combination of mutations from different clones.

Results and discussion

Of a total one hundred children recruited into this study, ninety two satisfied the inclusion criteria. The median age of the 92 patients (50 female, 42 male) was 7.3 years (range 3 months to 15 years). The geometric mean asexual parasitaemia of P. falciparum was 2.33% (95% confidence interval, 0.50–5.68).

The main observations resulting from the genotype analyses are presented as allele frequencies and haplotype frequencies in Table 1 and Figure 1, respectively. The frequency of mutations unveiled for both genes was high: 81 out of 92 isolates harbored the dhfr 51I mutation, 82 of 90 were dhps 59R mutants and 87 out of 92 displayed the 108N mutation (Table 1). Dhps mutants were less frequent than dhfr ones, but already well established among the parasite population (Table 1). Additionally, the proportion of parasites of parasites carrying more than one mutation at one or both genes (multiple mutants) proved to be significantly elevated (Figure 1). In this respect, attention is drawn to the observations that most of the parasite population carried triple pfdhfr mutations (pfdhfr 51I/59R/108N) and that approximately half harbored the quintuple mutant genotype pfdhfr 51I/59R/108N + pfdhfr 437G/540E (Figure 1) that have been shown to predict S/P treatment failure in East Africa [4, 5]. Indeed, in Mozambique, a previous study reported that two mutations at codon 59 in dhfr and codon 437 of dhps were actually enough to significantly predict parasitological failure [14]. Although in the present work no in vivo drug efficacy screening was carried out, the above genotype data appears to be consistent with previously reported S/P treatment failure for this region [15].

In a recent survey in Malawi, the pfdhfr 164L mutation, responsible for high level S/P resistance was reported [16]. In another study, which made use of a yeast expression system allowing detection of low levels DHFR-TS alleles, the presence of such mutants was also shown to occur in Tanzania [17]. These reports may be interpreted as early warning signs for a potential introduction of this genotype in Africa and prompted us to survey Mozambican parasites for this mutation. Pfdhfr 164L mutants were not identified in the present investigation however (Table 1), corroborating previous findings indicating that this mutation has not yet established itself in Africa [18, 19]. Although the number of isolates analysed in the current report may not be representative of the whole parasite population in this area, numerous other mutant alleles of pfdhfr and pfdhps, normally present in the region, were observed (Table 1). One of the possible explanations for the reported absence of this mutant could be that the 164L mutants may exist, but have not been detected using the standard PCR-RFLP protocol. Alternative explanations for the overall lack of this mutation among African parasites in general are put forward by Nzila and co-workers [12]. Their main premise is that the 164L mutation comes with a considerable fitness cost for the parasite and that the genetic composition of African parasites is less able to sustain it than their Asian counterparts. Nonetheless regular surveillance for this mutation should continue, in order to curtail the impact of S/P resistance spread in the African continent.

Conclusion

The observed high frequency of mutations in the S/P resistance-associated pfdhfr and pfdhps genes raises evidence-based concerns about the use of this drug as a component of first-line antimalarial treatment in Mozambique. The continued deployment of S/P will increase drug-based selective pressure which progressively raises the proportion of drug-resistant mutants and leaves combination therapy highly dependant on the sole effect of the S/P partner drug.

The study of the mechanisms associated with the selection of 164L mutation and continuous monitoring of this and other mutations are required, especially in areas where S/P is extensively used as first-choice antimalarial treatment, as in Maputo-Mozambique.

References

World Health Organization: Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. Document WHO/HTM/MAL/2006.1108, Geneva: WHO. 2006

Wongsrichanalai C, Pickard AL, Wernsdorfer WH, Meshnick SR: Epidemiology of drug-resistant malaria. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002, 2: 209-218. 10.1016/S1473-3099(02)00239-6.

Le Bras J, Durand R: The mechanisms of resistance toantimalarial drugs in Plasmodium falciparum. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2003, 17: 147-53. 10.1046/j.1472-8206.2003.00164.x.

Kublin JG, Dzinjalamala FK, Kamwendo DD, Malkin EM, Cortese JF, Martino LM, Mukadam RA, Rogerson SJ, Lescano AG, Molyneux ME, Winstanley PA, Chimpeni P, Taylor TE, Plowe CV: Molecular markers forfailure of sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine and chlorproguanil-dapsonetreatment of Plasmodium falciparum malaria. J Infect Dis. 2002, 185: 380-388. 10.1086/338566.

Mockenhaupt FP, Bousema TJ, Eggelte TA, Schreiber J, Ehrhardt S, Wassilew N, Otchwemah RN, Sauerwein RW, Bienzle U: Plasmodium falciparum dhfr but not dhps mutations associated with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine treatmentfailure and gametocyte carriage in northern Ghana. Trop Med Int Health. 2005, 10: 901-908. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01471.x.

Urdaneta L, Plowe C, Goldman I, Lal AA: Point mutations in dihydrofolate reductase and dihydropteroate synthase genes of Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Venezuela. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999, 61: 457-462.

Watkins WM, Mberu EK, Winstanley PA, Plowe CV: The Efficacy of antifolate antimalarial combination in africa: a predictive model based on pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic analyses. Parasitol Today. 1997, 13: 459-464. 10.1016/S0169-4758(97)01124-1.

Basco LK, Eldin de Pecoulas P, Wilson CM, Le Bras J, Mazabraud A: Point mutations in the dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase gene and pyrimethamine and cycloguanil resistance in Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1995, 69: 135-138. 10.1016/0166-6851(94)00207-4.

Basco LK, de Pecoulas PE, Le Bras J, Wilson CM: Plasmodium falciparum: molecular characterization of multidrug-resistant Cambodian isolates. Exp Parasitol. 1996, 82: 97-103. 10.1006/expr.1996.0013.

Plowe CV, Cortese JF, Djimde A, Nwanyanwu OC, Watkins WM, Winstanley PA, Estrada-Franco JG, Mollinedo RE, Avila JC, Cespedes JL, Carter D, Doumbo OK: Mutations in Plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase and dihydropteroate synthase and epidemiologic patterns of pyrimethamine-sulphadoxine use and resistance. J Infect Dis. 1997, 176: 1590-1596.

Zindrou S, Nguyen PD, Nguyen DS, Skold O, Swedberg G: Plasmodium falciparum: mutation pattern in the dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase genes of Vietnamese isolates, a novel mutation, and coexistence of two clones in a Thai patient. Exp Parasitol. 1996, 84: 56-64. 10.1006/expr.1996.0089.

Nzila A, Ochong E, Nduati E, Gilbert K, Winstanley P, Ward S, Marsh K: Why has the dihydrofolate reductase 164 mutation not consistently been found in Africa yet ?. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2005, 99: 341-346. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2004.07.002.

Duraisingh MT, Curtis J, Warhurst DC: Plasmodium falciparum: Detection of polymorphisms in the dihydrofolate reductase and dihydropteroato synthase genes by PCR and restriction digestion. Exp Parasitol. 1998, 89: 1-8. 10.1006/expr.1998.4274.

Alifrangis M, Enosse S, Khalil IF, Tarimo DS, Lemnge MM, Thompson R, Bygbjerg IC, Ronn AM: Prediction of Plasmodium falciparum resistance to sulphadoxine/pyrimethamine in vivo by mutations in the dihydrofolate reductase and dihydropteroate synthetase genes: a comparative study between sites of differing endemicity. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003, 69: 601-606.

Abacassamo F, Enosse S, Aponte JJ, Gomez-Olive FX, Quinto L, Mabunda S, Barreto A, Magnussen P, Ronn AM, Thompson R, Alonso PL, Abacassamo F, Enosse S, Aponte JJ, Gomez-Olive FX, Quinto L, Mabunda S, Barreto A, Magnussen P, Ronn AM, Thompson R, Alonso PL: Efficacy of chloroquine, amodiaquine, sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine and combination therapy with artesunate in Mozambican children with non-complicated malaria. Trop Med Int Health. 2004, 9: 200-208. 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01182.x.

Alker AP, Mwapasa V, Purfield A, Rogerson SJ, Molyneux ME, Kamwendo DD, Tadesse E, Chaluluka E, Meshnick SR: Mutations associated with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine and chlorproguanil resistance in Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Blantyre, Malawi. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005, 49: 3919-3921. 10.1128/AAC.49.9.3919-3921.2005.

Mutabingwa T, Nzila A, Mberu E, Nduati E, Winstanley P, Hills E, Watkins W: Chlorproguanil-dapsone for treatment of drug-resistant falciparum malaria in Tanzania. Lancet. 2001, 358: 1218-1223. 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06344-9.

Curtis J, Maxwell CA, Msuya FH, Mkongewa S, Alloueche A, Warhurst DC: Mutations in dhfr in Plasmodium falciparum infections selected by chlorproguanil-dapsone treatment. J Infect Dis. 2002, 186: 1861-1864. 10.1086/345765.

Hastings MD, Bates SJ, Blackstone EA, Monks SM, Mutabingwa TK, Sibley CH: Highly pyrimethamine-resistant alleles of dihydrofolate reductase in isolates of Plasmodium falciparum from Tanzania. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2002, 96: 674-676. 10.1016/S0035-9203(02)90349-4.

Acknowledgements

We wish to express our grattitude towards the staff of the C. Saúde de Bagamoyo (Mozambique) and Instituto de Higiene e Medicina Tropical/Centro de Malária e outras Doenças Tropicais (CMDT/IHMT/UNL, Portugal). This work was supported by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (SFRH/BD/10100/2002) – Portugal.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

NF and PF carried out most of the experimental procedures and contributed for the elaboration of the manuscript. VEdR and PC conceived the study, participated in its design and co-ordination and were involved in phases of the experimental work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Fernandes, N., Figueiredo, P., do Rosário, V.E. et al. Analysis of sulphadoxine/pyrimethamine resistance-conferring mutations of Plasmodium falciparum from Mozambique reveals the absence of the dihydrofolate reductase 164L mutant. Malar J 6, 35 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-6-35

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-6-35