Abstract

Background

Malaria still has significant impacts on the world; particularly in Africa, South America and Asia where spread over several millions of people and is one of the major causes of death. When chloroquine diphosphate (CQDP) lost its efficiency as a first-line anti-malarial drug, this was a major setback in the effective control of malaria. Currently, malaria is treated with a combination of two or more drugs with different modes of action to provide an adequate cure rate and delay the development of resistance. Clearly, a new effective and non-toxic anti-malarial drug is urgently needed.

Methods

All metal-chloroquine (CQ) and metal-CQDP complexes were synthesized under N2 using Schlenk techniques. Their interactions with haematin and the inhibition of β-haematin formation were examined, in both aqueous medium and near water/n-octanol interfaces at pH 5. The anti-malarial activities of these metal- CQ and metal-CQDP complexes were evaluated in vitro against two strains, the CQ-susceptible strain (CQS) 3D7 and the CQ-resistant strain (CQR) W2.

Results

The previously synthesized Au(CQ)(Cl) (1), Au(CQ)(TaTg) (2), Pt(CQDP)2Cl2 (3), Pt(CQDP)2I2 (4), Pd(CQ)2Cl2 (5) and the new one Pd(CQDP)2I2 (6) showed better anti-malarial activity than CQ, against the CQS strain; moreover, complexes 2, 3 and 4 were very active against CQR strain. These complexes (1–6) interacted with haem and inhibited β-haematin formation both in aqueous medium and near water/n-octanol interfaces at pH 5 to a greater extent than chloroquine diphosphate (CQDP) and other known metal-based anti-malarial agents.

Conclusions

The high anti-malarial activity displayed for these metal-CQ and metal-CQDP complexes (1–6) could be attributable to their effective interaction with haem and the inhibition of β-haematin formation in both aqueous medium and near water/n-octanol interfaces at pH 5.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Approximately 3.3 billion people, one half of the world’s population, live in at-risk regions for malaria infection. In 2013, an estimated 207 million episodes of malaria occurred, and approximately 627,000 people died [1]. Of the five typically recognized Plasmodium species causing this disease in humans, Plasmodium falciparum is responsible for about 95% of malaria worldwide and has a mortality rate of 1–3%, and Plasmodium vivax for most morbidity, additionally representing a reservoir of latent infection that hampers current control and future elimination efforts [2, 3].

When chloroquine resistant (CQR) malaria parasites started to emerge in Asia and South America and spread from Asia to Africa, and lost its efficiency as a first line anti-malarial drug, this was a major setback to the effective control of malaria. Currently, malaria is treated with a combination of two or more drugs with different modes of action to provide an adequate cure rate and delay development of resistance.

A strategy for the development of alternative therapies against malaria has been based on the modification of compounds with known or potential activity through the incorporation of a transition metal into the molecular structure, this modification is important within biological systems due to the binding capability and reactivity of the transition metals, which are determined by the d orbitals [4]. A variety of metal complexes has been developed as possible anti-malarial agents [5–8], progressed from simple “synthesis/activity” to complex insights into their mechanisms of action, these concepts open new perspectives in drug design, for example Sanchez-Delgado and Navarro groups have proposed the modification of CQ through the incorporation of a transition metal into the molecular structure. Indeed, several metal centres (Rh, Ru, Ir and Au) have been used finding that the most significant results have been obtained for the centers of ruthenium [9, 10] and gold [11, 12].

Encouraged by these interesting biological results the studies of the mechanism of action of these metal-chloroquine complexes ([RuCl2(CQ)]2 and [Au(CQ)(PPh3)]PF6) were evaluated on two important targets, Fe(III)PPIX and DNA [13, 14], finding that the main mechanism of anti-malarial action of these [RuCl2(CQ)]2 and [Au(CQ)(PPh3)]PF6 complexes against resistant strains of P. falciparum was the inhibition of β-haematin formation. Both the enhanced activity and the ability of these compounds to lower CQ resistance are related to the high lipophilicity of the metal complexes and the important structural modification of the CQ structure imposed by the presence of the metal-containing fragment.

Taking into account the importance of the interactions of these metal compounds with the specific targets Fe(III)PPIX and the relevance of the inhibition of β-haematinin order to increase anti-plasmodial activity and avoid parasite resistance, the interaction of six metal-CQ (metal: Au, Pt and Pd) complexes with ferriprotoporphyrin, their ability to inhibit the haem aggregation at water/lipid interfaces and their anti-malarial activity against 3D7 and W2 strains (CQ-susceptible strain and CQ-resistant strain, respectively) were assessed in the present work. Worthy of mentioning, that the cytotoxic activity against the six tumor cell lines, of five of these metal-CQ complexes have already been reported [15, 16] that significant activity was attributed mainly to their interaction with the DNA. Additionally, the synthesis and characterization of the new Pd(CQDP)2I2 complex were reported here.

Methods

All manipulations were carried out under N2 using common Schlenk techniques. Solvents were purified by standard procedures immediately prior to use. Chloroquine diphosphate (CQDP), chloride haemin, buffers and solvents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. All other commercial reagents were used without further purification. Metal–CQ and Metal–CQDP (1–5) complexes were prepared according to the literature [15–17]. The NMR spectra were obtained in a DMSO solution in a Bruker AVANCE 500 spectrometer. 1H NMR shifts were recorded relative to residual proton resonances in the deuterated solvent. IR spectra were obtained with a Nicolet Magna IR 560 spectrometer. ESI mass spectra were obtained by using a Thermo FINNIGAN LXQ with methanol as the solvent. UV–vis spectra and all the spectrophotometric studies experiments were performed on an Agilent 8453 diode-array spectrophotometer.

Synthesis and characterization of complex Pd(CQDP)2I2 (6)

A solution of K2[PdCl4] (65.3 mg, 0.2 mmol) in water (20 mL) was stirred until complete dissolution was achieved, an excess (20-fold) of KI was added. Then, CQDP dissolved in water (206.4 mg, 0.4 mmol) was added. The stirring was continued for 1 h at room temperature, and a brown precipitate was obtained. This was collected by filtration, washed with water, and dried under vacuum. Spectroscopic and analytical characterization of this complex was described in Additional file 1.

In vitro anti-malarial activity

The two strains, 3D7, the CQ-susceptible strain (isolated in West Africa; obtained from MR4, VA, USA), and W2 (isolated in Indochina; obtained from MR4, VA, USA), the CQ-resistant strain, were maintained in culture in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK), supplemented with 10% human serum (Abcys S.A. Paris, France) and buffered with 25 mM HEPES and 25 mM NaHCO3. Parasites were grown in A-positive human blood (Etablissement Français du Sang, Marseille, France) under controlled atmospheric conditions that consisted of 10% O2, 5% CO2 and 85% N2 at 37°C with a humidity of 95%.

The two strains were synchronized twice with sorbitol before use [18], and clonality was verified every 15 days through PCR genotyping of the polymorphic genetic markers msp1 and msp2 and microsatellite loci [19, 20]; additionally, clonality was verified each year by an independent laboratory from the Worldwide Anti-malarial Resistance Network (WWARN).

Chloroquine diphosphate (CQDP) was purchased from Sigma (Saint Louis, MO). CQDP was resuspended in water in concentrations ranging between 5 to 3200 nM. The synthetic compounds were resuspended in DMSO and then diluted in RPMI-DMSO (99v/1v) to obtain final concentrations ranging from 1 nM to 100 μM.

For in vitro isotopic microtests, 25 μL/well of anti-malarial drug and 200 μL/well of the parasitized red blood cell suspension (final parasitaemia, 0.5%; final haematocrit, 1.5%) were distributed into 96 well plates. Parasite growth was assessed by adding 1 μCi of tritiated hypoxanthine with a specific activity of 14.1 Ci/mmol (Perkin-Elmer, Courtaboeuf, France) to each well at time zero. The plates were then incubated for 48 h in controlled atmospheric conditions. Immediately after incubation, the plates were frozen and thawed to lyse erythrocytes. The contents of each well were collected on standard filter microplates (Unifilter GF/B; Perkin-Elmer) and washed using a cell harvester (Filter-Mate Cell Harvester; Perkin-Elmer). Filter microplates were dried, and 25 μL of scintillation cocktail (Microscint O; Perkin-Elmer) was placed in each well. Radioactivity incorporated by the parasites was measured with a scintillation counter (Top Count; Perkin-Elmer).

The IC50, the drug concentration able to inhibit 50% of parasite growth, was assessed by identifying the drug concentration corresponding to 50% of the uptake of tritiated hypoxanthine by the parasite in the drug-free control wells. The IC50 value was determined by non-linear regression analysis of log-based dose–response curves (Riasmart™, Packard, Meriden, USA). IC50 are expressed as geometric means of 6 experiments.

Interaction with haematin

The association constant of compounds metal-CQ with ferriprotoporphyrin IX (Fe(III)PPIX) was measured as described previously [21]. Briefly, a stock solution of haemin was prepared by dissolving 3.5 mg of haemin in 15 mL DMSO. Aqueous-DMSO (40% v/v) solutions of Fe(III)PPIX (pH 7.5) were prepared daily by mixing 140 μL haemin stock solution with 4 mL DMSO and 1 mL 0.2 M (Tris; Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane) Tris buffer (pH 7.5) and completed to 10 mL with doubly distilled deionized water. The concentration of Fe(III)PPIX in this solutions was 4 μM and absorbance readings were recorded at 402 nm. The reference cell containing 40% v/v DMSO, 0.020 M Tris pH 7.5 was also titrated with each complex in order to blank out the absorbance of the drug. The data were fitted to the equation A = (A0 + A∞K[C])/(1 + K[C]) for a 1:1 complexation model using nonlinear least squares fitting, strictly following the procedure of Egan et al.[22], with omission of the first few data points at very low drug-to-haematin ratio, where the fit is poor. A0 is the absorbance of haemin before addition of complex, A∞ is the absorbance for the drug–haemin adduct at saturation, A is the absorbance at each point of the titration, and K is the conditional association constant.

Inhibition of β-haematin formation

The transformation of haemin to β-haematin in acidic acetate solutions was studied using infrared spectroscopy using the method developed by Egan et al.[22]. The IC50 of β-Haematin formation in buffer assay was performed according to Dominguez [23]. Briefly, a solution of haemin (50 μL, 4 mM), dissolved in DMSO, was distributed in 96-well micro plates. The complex was dissolved in DMSO and added in triplicate in test wells (50 μL) to final concentrations of 0–20 mM/well. Controls contained water and DMSO. Haemozoin formation was initiated by the addition of acetate buffer (100 μL 0.2 M, pH 4.4). Plates were incubated at 37°C for 48 h to allow completion of the reaction and centrifuged at 4,000 RPM × 15 min. After discarding the supernatant, the pellet was washed twice with DMSO (200 μL) and finally dissolved in NaOH (200 μL, 0.2 N). The solutions were further diluted 1:2 with NaOH (0.1 N) and absorbance recorded at 405 nm. The results were expressed as a percentage of inhibition of haemozoin formation.

β-Haematin formation at a water/octanol interface was followed according to a method proposed by Egan and coworkers [24] and modified by Martínez et al.[25]. Haemin was dissolved in 0.1 M NaOH solution to generate haematin and acetone was added until the acetone: water ratio was 4: 6; the final solution contained 15 mg haematin/mL. A sample of this solution (200 μL) was carefully introduced close to the interface between n-octanol (2 mL) and aqueous acetate buffer (5 mL, 8 M; pH 4.9) in a cylindrical vial with an internal diameter of 2.5 cm. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 2 h and at the end of the incubation the product (β-haematin) was isolated by centrifugation. The pellet was collected and washed twice with DMSO (2 mL), centrifuged again for 20 min, washed with 2 mL of ethanol and finally dissolved in 25 mL of 0.1 M NaOH for spectrophotometric quantification. For the haem aggregation inhibition activity measurements the appropriate amount of the drug (23 mM in DMSO) was dissolved; after stirring for 30 min to equilibrate the drug between the two phases, the haematin solution was added close to the interface and the procedure was followed as described above. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and characterization of complex Pd(CQDP)2(I)2 (6)

The palladium-chloroquine diphosphate complex was synthesized at room temperature in water. An excess of KI was added to the solution of K2[PdCl4] in order to displace all chloride ligands; subsequently, CQDP was added in a ratio 2:1 with respect to palladium salt, displaced two iodide ligands leads to the new complex(6), which was isolated in good yields as air stable brown solid. Elemental analyses of this complex are in agreement with the molecular formula proposed. The IR spectra of the complexes displayed peaks clearly associated with the presence of the coordinated CQDP. The ESI-MS spectrum of complex displayed a peak of high intensity corresponding to a molecular ion (M - 4H3PO4) at m/z 1000.03. The molar conductivity values obtained for the complex is in the range for 1:4 electrolytes dissolved in DMF [26], corresponding to four phosphates (H2PO4−) of CQDP in the complex. All NMR signals could be unequivocally assigned on the basis of 1D and 2D, Correlation spectroscopy (COSY), Heteronuclear Multiple Quantum Correlation (HMQC) and Heteronuclear Multiple Bond Correlation (HMBC) experiments for both complexes (for complete NMR data see Annex 1; atom numbering for CQDP in Figure 1). The 1H and 31C chemical shift variation of each signal with respect to those of the free ligand (Δδ) was used as a parameter to deduce the mode of bonding of CQDP to the metal. It has been previously shown [9–12, 27] that the largest variations are always observed for the protons and carbons located in the vicinity of the N-atom attached to the metal. The largest shift with respect to the free ligand (CQDP) was observed for NH and H1’ in the 1H NMR spectra and C4 in the 31C NMR spectra (Table 1). All other chloroquine protons and carbons showed smaller displacements, indicating that CQDP is bound to the palladium through the NH atom of the secondary amine, a good donor site in this molecule. Additionally, one signal was observed in the 31P-NMR corresponding to the H2PO4− group of CQDP (see Additional file 1). Based on the experimental data available, the formulation for the new palladium-chloroquine diphosphate compounds corresponds to 16-electron Pd(II) complexes in the usual d8 square planar coordination geometry, of trans configuration due to steric repulsion between the two chloroquine diphosphate ligands.

Since the biological test are carried out using DMSO solution, it is important to mention that the metal complexes reported here are stable in this solvent, their NMR spectra in DMSO-d6 remain unchanged for several days at room temperature, showing no evidence of displacement of the CQ ligand by the solvent or any decomposition of these complexes. Worthy of mentioning is that only AuClCQ showed color change after 12 hours, however the 1HNMR spectrum showed the characteristic peaks for CQ ligand coordinated to the gold.

Anti-malarial activity

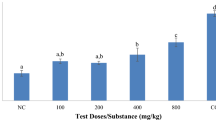

In vitro anti-malarial activity studies were carried out in Plasmodium falciparum parasite, using a chloroquine-susceptible (CQS) strain (3D7) and chloroquine-resistant (CQR) strain (W2); the results are given in Table 2. The anti-malarial drug CQDP was used as a reference. All tested metal-CQ and metal-CQDP complexes displayed very high anti-malarial activity against the CQS strain (3D7), in general all metal complexes showed better activity than CQDP, except Pd(CQDP)2I2 which showed the less activity (IC50 = 24 nM). Suggesting that, metals like gold and platinum achieved to improve the antiplasmodial activity of CQDP. However, this trend was not observed when the studied metal complexes were tested against the CQR strain (W2), the result revealed that Pt(CQDP)2Cl2 was the most active compound (IC50 = 89 nM) of these series, followed by Au(CQ)(TaTg) and Pt(CQDP)2I2 which displayed similar antiplasmodial activity IC50 = 175 nM and IC50 = 177 nM respectively; these three complexes were clearly more active that CQDP (IC50 = 406 nM), the rest of the studied metal complexes were less active than CQDP, although not clear trend was observed, it is noticeable that Pt(CQDP)2Cl2 was the most active complex against CQS and CQR. The IC50 values found in the 3D7 CQS strain are equivalent to those found in CQS laboratory strains or field isolates for the ferroquine, the 7-chloro-4-[(2-N,N-dimethylaminomethyl)ferrocenyl-methylamino]quinoline, ruthenoquine or 2-phenylindoles and 3-ferrocenylmethyl-2-phenylindoles but those obtained in the W2 CQR strain are higher than those found in CQR laboratory strains or field isolates for the two metalloquines [28–32]. However, the in vitro activity of these different compounds exhibited higher activity than those in the micromolar range obtained with pyrazole palladium or platinum complexes [33], rhenium-4-aminoquinolines [34], ferrocene-ciprofloxacin complexes [35, 36] and ferrocenyl-chalcones [37]. All tested metal complexes are more active against CQS than CQR. These data suggest that the activity of present compounds is correlated with that of CQ. Previous studies suggested that metal coordination to CQ reduces or abolished cross-resistance [28, 31]. The ferroquine and ruthenoquine were correlated to each other but not with CQ, confirming the lack of cross-resistance. However, in some works, some rhenium bioorganometallics based on the 4-aminoquinoline structure were less active in vitro against the W2 CQR strain than the 3D7 CQS [34]. A larger number of strains with several susceptibility profiles should be necessary to properly assess the cross-resistance between the present compounds and CQ and conclude.

Interaction with haemin and inhibition of β-haematin formation

Chloroquine and its metal derivatives have shown that they can act through the formation of adducts with ferriprotoporphyrin IX, thus blocking haemozoin formation [15, 16, 38]. Indeed, in previous studies we have indicated that the anti-malarial activity of metal-CQ complexes often correlated with the interaction with haemin and β –haematin inhibition (10,13,14]. Following similar studies to those published previously, the association constant of complexes 1–6 with ferriprotoporphyrin IX (Fe(III)PPIX) were determined (Table 2). This association was followed by spectrophotometric titration at the 402 nm Soret band in aqueous DMSO at pH 5, to the equation for a 1:1 complexation model using nonlinear least squares fitting, strictly following the procedure of Egan et al. [21]. As an example, in Figure 2 is shown the needed concentration of complex 6 to reach the saturation point, and the hypochromism was approximately 70%. The log K value of 5.01 ± 0.01 obtained for CQDP under the present experimental conditions (pH 7.5) is in excellent agreement with the value reports for this method [21], in the case of log K for the studied complexes (1–6) was obtained fitted in a strictly analogous manner, the range of log K values are between 4.05 and 4.87 (Table 2), this indicates that complexes 1–6 interact with haematin comparably that CQDP does, under used conditions. Additionally, it is important of mentioning that these values are in the range of ferroquine, which has demonstrated high anti-malarial activity [5].

A first approximation to study the inhibition of β-haematin formation was done qualitatively using FTIR spectroscopy, monitoring the absence of characteristic β-haematin bands at 1660 and 1210 cm−1[22] which are obtained in the control experiment in the absence of CQ and studied metal complexes. However, the IR spectra obtained when the same experiment was done in the presence of 3 equivalents of CQ and each studied metal complexes (separate experiments) showed the absence of the bands at 1660 and 1210 cm−1 making evident that β-haematin was not produced, similarly to previous observations for CQ, other organic antiplasmodial compounds [22] and metal-CQ complexes [5].

The interesting results previously discussed motivated the study of the effect of complexes 1–6 on the haem aggregation inhibition activity assays (HAIA), which was determined using two set of experiments, the first one was carried out in buffer while a second set was performed in an interface n-octanol/ aqueous buffer interface; these results were compared to those ones obtained for CQDP as control (Table 2).

The IC50 values measured for these complexes in acetate buffer at pH 5 shown that complexes 1–6 inhibit the haem aggregation process at higher IC50 than the one obtained for CQDP. Similar results were obtained by this method for [RuCl2(CQ)]2[13] and [Au(CQ)(PPh3)]PF6[14] complexes previously published, where no correlation was observed between the inhibition of the haem aggregation in buffer with their anti-malarial activities against CQR strains. Therefore, a more realistic condition in the interfaces where the β-haematin assembles rapidly and spontaneously occurred was used following an adaptation of the procedure described by Egan et al.[24] and reported by Sánchez-Delgado et al.[25], in which the haematin is carefully introduced close to the interface after the drug has been equilibrated between the two phases, the overall aggregation process is much faster (60 min) through this method. The activity trend changes drastically with respect to the results of the assay in aqueous buffer. The complexes 1–6 was comparable or 2.3 times better inhibitor than CQDP on the inhibition of the haem aggregation near the interface, providing a plausible explanation for the enhanced anti-plasmodial activity displayed for these studied metal complexes.

Conclusion

The synthesis and characterization of a new Pd-CQDP (6) complex was achieved and together with complexes 1–5 were tested against two strain of malarial parasite, finding that all these complexes displayed very high anti-malarial activity against the CQS strain (3D7), while only complexes 2, 3 and 4 were up to four times more active than CQDP against CQR strain (W2). Complexes 1–6 interact with haem and inhibit β-haematin formation to a greater extent than chloroquine diphosphate (CQDP) and other known metal-based anti-malarial agents. Putting together all of these results, it is possible to suggest that the enhanced of the antiplasmodial activity displayed for these studied metal complexes is related to their ability to inhibit β-haematin formation.

References

WHO: World Malaria Report. 2012, Geneva: World Health Organization, [http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/world_malaria_report_2012/wmr2012_no_profiles.pdf]

Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV): MMV Target Product Profiles. 2010, [http://www.mmv.org/research-development/essential-informationscientists/target-product-profiles. Accessed 15 September 2013]

Anstey NM, Russell B, Yeo TW, Price RN: The pathophysiology of vivax malaria. Trends Parasitol. 2009, 25: 220-227. 10.1016/j.pt.2009.02.003.

Farrel NP: Uses of Inorganic Chemistry in Medicine. 1999, Virginia, USA: Royal Society of Chemistry

Biot C, Castro W, Botted CY, Navarro M: The therapeutic potential of metal-based antimalarial agents: implications for the mechanism of action. Dalton Trans. 2012, 41: 6335-6349. 10.1039/c2dt12247b.

Ajibade PA, Kolawole GA: Synthesis, characterization and antiprotozoal studies of some metal complexes of antimalarial drugs. Transition Met Chem. 2008, 33: 493-497. 10.1007/s11243-008-9070-2.

Salas PF, Herrmann C, Orvig C: Metalloantimalarials. Chem Rev. 2013, 113: 3450-3492. 10.1021/cr3001252.

Pena AC, Penacho N, Mancio-Silva L, Neres R, Seixas JD, Fernandes AC, Romão CC, Mota MM, Bernardes GJL, Pamplona A: A novel carbon monoxide-releasing molecule fully protects mice from severe malaria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012, 56: 1281-1290. 10.1128/AAC.05571-11.

Sánchez-Delgado RA, Navarro M, Pérez H, Urbina JA: Toward a novel metal-based chemotherapy against tropical diseases. 2. Synthesis and antimalarial activity in vitro and in vivo of new ruthenium − and rhodium − chloroquine complexes. J Chem Med. 1996, 39: 1095-1099. 10.1021/jm950729w.

Glans L, Ehnbom A, de Kock C, Martínez A, Estrada J, Smithb PJ, Haukka M, Sánchez-Delgado RA, Nordlander E: Ruthenium(II) arene complexes with chelating chloroquine analogue ligands: synthesis, characterization and in vitro antimalarial activity. Dalton Trans. 2012, 41: 2764-2773. 10.1039/c2dt12083f.

Sánchez-Delgado RA, Navarro M, Pérez H: Toward a novel metal-based chemotherapy against tropical diseases. 3. Synthesis and antimalarial activity in vitro and in vivo of the new gold − chloroquine complex [Au(PPh3)(CQ)]PF6. J Chem Med. 1997, 40: 1937-1939. 10.1021/jm9607358.

Navarro M, Vásquez F, Sánchez-Delgado RA, Pérez H, Sinou V, Schrével J: Toward a novel metal-based chemotherapy against tropical diseases. 7. Synthesis and in vitro antimalarial activity of new gold − chloroquine complexes. J Chem Med. 2004, 47: 5204-5209. 10.1021/jm049792o.

Rajapakse CSK, Martínez A, Naoulou B, Jarzecki AA, Suárez L, Deregnaucourt C, Sinou V, Schrevel J, Musi E, Ambrosini G, Schwartz GK, Sánchez-Delgado RA: Synthesis, characterization, and in vitro antimalarial and antitumor activity of new ruthenium(II) complexes of chloroquine. Inorg Chem. 2009, 48: 1122-1131. 10.1021/ic802220w.

Navarro M, Castro W, Martínez A, Sánchez-Delgado RA: The mechanism of antimalarial action of [Au(CQ)(PPh3)]PF6: structural effects and increased drug lipophilicity enhance heme aggregation inhibition at lipid/water interfaces. J Inorg Biochem. 2011, 105: 276-282. 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2010.11.005.

Navarro M, Castro W, González S, Abad MJ, Taylor P: Synthesis and anticancer activity of gold(I)-chloroquine complexes. J Mex Chem Soc. 2013, 57: 220-229.

Navarro M, Castro W, Higuera-Padilla AR, Sierraalta A, Abad MJ, Taylor P, Sánchez-Delgado RA: Synthesis, characterization and biological activity of trans-platinum(II) complexes with chloroquine. J Inorg Biochem. 2011, 105: 1684-1691. 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2011.09.024.

Navarro M, Prieto Pena N, Colmenares I, Gonzalez T, Arsenak M, Taylor P: Synthesis and characterization of new palladium–clotrimazole and palladium–chloroquine complexes showing cytotoxicity for tumor cell lines in vitro. J Inorg Biochem. 2006, 100: 152-157. 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2005.10.013.

Lambros C, Vanderberg JP: Synchronization of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocytic stages in culture. J Parasitol. 1979, 65: 418-420. 10.2307/3280287.

Bogreau H, Renaud F, Bouchiba H, Durand P, Assi SB, Henry MC, Garnotel E, Pradines B, Fusai T, Wade B, Adehossi E, Parola P, Kamil MO, Puijalon O, Rogier C: Genetic diversity and structure of African Plasmodium falciparum populations in urban and rural areas. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006, 74: 953-959.

Henry M, Diallo I, Bordes J, Ka S, Pradines B, Diatta B, M'Baye PS, Sane M, Thiam M, Gueye PM, Wade B, Touze JE, Debonne JM, Rogier C, Fusai T: Urban malaria in Dakar, Senegal: chemosusceptibility and genetic diversity of Plasmodium falciparum isolates. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006, 75: 146-151.

Egan TJ, Mavuso WW, Ross DC, Marques HM: Thermodynamic factors controlling the interaction of quinoline antimalarial drugs with ferriprotoporphyrin IX. J Inorg Biochem. 1997, 68: 137-145. 10.1016/S0162-0134(97)00086-X.

Egan TJ, Ross DC, Adams PA: Quinoline anti-malarial drugs inhibit spontaneous formation of β-haematin (malaria pigment). FEBS Lett. 1994, 352: 54-57. 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00921-X.

Domínguez JN, León C, Rodrigues J, Gamboa de Domínguez N, Rosenthal PJ: Synthesis and antimalarial activity of sulfonamide chalcone derivatives. II Fármaco. 2005, 60: 307-311.

Egan TJ, Chen J, de Villiers KA, Mabotha TE, Naidoo KJ, Ncokazi KK, Langford SJ, McNaughton D, Pandiancherri S, Wood BR: Haemozoin (β-haematin) biomineralization occurs by self-assembly near the lipid/water interface. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580: 5105-5110. 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.08.043.

Martínez A, Rajapakse CSK, Jalloh D, Dautriche C, Sánchez-Delgado RA: The antimalarial activity of Ru–chloroquine complexes against resistant Plasmodium falciparum is related to lipophilicity, basicity, and heme aggregation inhibition ability nearwater/n-octanol interfaces. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2009, 14: 863-871. 10.1007/s00775-009-0498-4.

Geary WJ: The use of conductivity measurements in organic solvents for the characterisation of coordination compounds. Coord Chem Rev. 1971, 7: 81-122. 10.1016/S0010-8545(00)80009-0.

Sundquist WI, Bancroft DP, Lippard SJ: Synthesis, characterization, and biological activity of cis-diammineplatinum(II) complexes of the DNA intercalators 9-aminoacridine and chloroquine. J Am Chem Soc. 1990, 112: 1590-1596. 10.1021/ja00160a044.

Henry M, Briolant S, Fontaine A, Mosnier J, Baret E, Amalvict R, Fusai T, Fraisse L, Rogier C, Pradines B: In vitro activity of ferroquine is independent of polymorphisms in transport proteins genes implicated in quinoline resistance in Plasmodium falciparum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008, 52: 2755-2759. 10.1128/AAC.00060-08.

Pradines B, Tall A, Rogier C, Spiegel A, Mosnier J, Marrama L, Fusai T, Millet P, Panconi E, Trape JF, Parzy D: In vitro activities of Ferrochloroquine against 55 Senegalese isolates of Plasmodium falciparum in comparison with those of standard antimalarial drugs. Trop Med Int Health. 2002, 7: 265-270. 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00848.x.

Pradines B, Fusai T, Daries W, Laloge V, Rogier C, Millet P, Panconi E, Kombila M, Parzy D: Ferrocene-chloroquine analogues as antimalarial agents: in vitro activity of ferrochloroquine against 103 Gabonese isolates of Plasmodium falciparum. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001, 48: 179-184. 10.1093/jac/48.2.179.

Dubar F, Egan TJ, Pradines B, Kuter D, Ncokazi KK, Forge D, Pal JF, Pierrot C, Kalamou H, Khalife J, Buisine E, Rogier C, Vezin H, Forfar I, Slomianny C, Trivelli X, Kaoishnikov S, Leiserowitz L, Dive D, Biot C: The antimalarial ferroquine: role of the metal and intramolecular hydrogen bond in activity and resistance. ACS Chem Biol. 2011, 6: 275-287. 10.1021/cb100322v.

Quirante J, Dubar F, Gonzalez A, Lopez C, Cascante M, Cortes R, Forfar I, Pradines B, Biot C: Ferrocene-indole hybrids for cancer and malaria therapy. J Org Chem. 2011, 696: 1011-1017. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2010.11.021.

Quirante J, Ruiz D, Gonzalez A, López C, Cascante M, Cortés R, Messeguer R, Calvis C, Baldomà L, Pascual A, Guérardel Y, Pradines B, Font-Bardía M, Calvet T, Biot C: Platinum(II) and palladium(II) complexes with (N, N') and (C, N, N')- ligands derived from pyrazole as anticancer and antimalarial agents: synthesis, characterization and in vitro activities. J Inorg Biochem. 2011, 105: 1720-1728. 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2011.09.021.

Arabicia R, Dubar F, Pradines B, Forbar I, Dive D, Klahn H, Biot C: Synthesis and antimalarial activies of rhenium bioorganometallics based on the 4-aminoquinoline structure. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010, 18: 8085-8091. 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.09.005.

Dubar F, Anquetin G, Pradines B, Dive D, Khalife J, Biot : Antimalarial activity enhancement of ciprofloxacin by using a double prodrug/bioorganometallic approach. J Med Chem. 2009, 52: 7954-7957. 10.1021/jm901357n.

Dubar F, Wintjens R, Martins-Duarte ES, Vommaro RC, Souza W, Dive D, Pierrot C, Pradines B, Wohlkonig A, Khalife J, Biot C: Ester prodrugs of ciprofloxacin as DNA-gyrase inhibitors: synthesis, antiparasitic evaluation and docking studies. Med Chem Commun. 2011, 2: 430-435. 10.1039/c1md00022e.

Kumar K, Pradines B, Madamet M, Amalvict R, Kumar V: 1H-1,2,3-triazole tethered mono- and bis-ferrocenylchalcone-b-lactam conjugates: synthesis and antimalarial evaluation. Eur J Med Chem. 2014, 86: 113-212.

Dorn A, Stoffel R, Matile H, Bubendorf A, Ridley R: Malarial haemozoin/betahaematin supports haem polymerization in the absence of protein. Nature. 1995, 374: 269-271. 10.1038/374269a0.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr. Christophe Biot for his assistance and Prof. Roberto Sánchez-Delgado for his assistance with β-Haematin formation at interface experiments. The study was supported by the 'Délégation Générale pour l'Armement' (grant no PDH-2-NRBC-4-B1-402).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MN and WC performed the syntheses, characterization and the inhibition of b-haematin formation studies. MM, RA, NB and BP carried out the in vitro evaluation of the anti-malarial activity. MN and BP conceived and coordinated the study. MN, WC and BP drafted the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Navarro, M., Castro, W., Madamet, M. et al. Metal-chloroquine derivatives as possible anti-malarial drugs: evaluation of anti-malarial activity and mode of action. Malar J 13, 471 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-13-471

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-13-471