Abstract

Background

Cytoadherence of infected red blood cells to brain endothelium is causally implicated in malarial coma, one of the severe manifestations of falciparum malaria. Cytoadherence is mediated by specific binding of variant parasite antigens, expressed on the surface of infected erythrocytes, to endothelial receptors including, ICAM-1, VCAM and CD36. In fatal cases of severe falciparum malaria with coma, blood vessels in the brain are characteristically congested with infected erythrocytes. Brain sections from a fatal case of knowlesi malaria, but without coma, were similarly congested with infected erythrocytes. The objective of this study was to determine the binding phenotype of Plasmodium knowlesi infected human erythrocytes to recombinant human ICAM-1, VCAM and CD36.

Methods

Five patients with PCR-confirmed P. knowlesi malaria were recruited into the study with consent between April and August 2010. Pre-treatment venous blood was washed and cultured ex vivo to increase the proportion of schizont-infected erythrocytes. Cultured blood was seeded into Petri dishes with triplicate areas coated with ICAM-1, VCAM and CD36. Following incubation at 37°C for one hour the dishes were washed and the number of infected erythrocytes bound/mm2 to PBS control areas and to recombinant human ICAM-1 VCAM and CD36 coated areas were recorded. Each assay was performed in duplicate. Assay performance was monitored with the Plasmodium falciparum clone HB3.

Results

Blood samples were cultured ex vivo for up to 14.5 h (mean 11.3 ± 1.9 h) to increase the relative proportion of mature trophozoite and schizont-infected red blood cells to at least 50% (mean 65.8 ± 17.51%). Three (60%) isolates bound significantly to ICAM-1 and VCAM, one (20%) isolate bound to VCAM and none of the five bound significantly to CD36.

Conclusions

Plasmodium knowlesi infected erythrocytes from human subjects bind in a specific but variable manner to the inducible endothelial receptors ICAM-1 and VCAM. Binding to the constitutively-expressed endothelial receptor CD36 was not detected. Further work will be required to define the pathological consequences of these interactions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Coma is one of the manifestations of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in children and adults [1, 2] and it carries a poor prognosis. The accumulation of cytoadherent parasitized erythrocytes in post-capillary venules of the brain is strongly causally implicated in precipitating malarial coma [3–5]. Adherence to brain and other endothelial surfaces is mediated by the expression of variant parasite-derived proteins (Pf EMP1 var family) on the P. falciparum infected erythrocyte surface [6]. PfEMP1 proteins predominantly bind to CD36, but also to inducible Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1 (ICAM-1) [7–10]. Binding to up-regulated ICAM-1 is particularly important in cytoadherence to brain endothelium because CD36 is not expressed in this endothelial compartment [8, 9].

Malarial coma is rare in other infections by the human host-adapted Plasmodium species and coma has not been a feature of severe and fatal zoonotic Plasmodium knowlesi malaria [11–13]. However, post mortem examination of a fatal case of severe knowlesi malaria without coma showed brain capillaries and venules congested with infected erythrocytes [14]. Expressed parasite variant surface antigens had been described in experimental P. knowlesi infections of rhesus monkeys before PfEMP1 was identified in P. falciparum[15]. Plasmodium knowlesi surface proteins were named Schizont-Infected Cell Agglutination Antigens (SICA) and are encoded by the SICAvar gene family [16]. Although distantly related, SICAvar proteins share binding signature motifs with PfEMP1 proteins [17]. The remarkable histological similarity between brain sections from fatal P. knowlesi malaria and fatal cases of severe falciparum malaria with coma [14, 18], particularly the accumulation of infected erythrocytes in brain microvasculature, led to the design of this study to test the binding characteristics of P. knowlesi isolates from patients [9].

Methods

Patient recruitment

Patients with malaria admitted to Hospital Sarikei in Sarawak, Malaysian Borneo were recruited, with informed consent, into this study between April and August 2010. The study was approved by the Malaysian Ministry of Health Medical Research and Ethics Committee. Infecting species was confirmed by Plasmodium species-specific nested-PCR assays [19] and only patients with single species infections were retained in the study.

Blood collection and ex vivo parasite development

Approximately 2.5 mL of pre-treatment venous blood from each patient was collected into EDTA. RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 20 mM D-glucose, 25 mM HEPES, 25 mg/ml gentamicin sulphate, 15% human AB plasma with 0.2 mM hypoxanthine was used for parasite culture. Gently washed loosely packed cells from each patient were re-suspended in culture medium to approximately 5% haematocrit and cultured at 37°C under 5% O2, 5% CO2 and 90% N2. Thin blood film microscopy was used to follow parasite development until at least half the parasites had developed into late trophozoites (parasites with dense cytoplasm and undivided nuclear chromatin mass) and schizonts (at least three divided nuclear chromatin masses with pigment granules). See Figure 1a and 1b.

Plasmodium knowlesi static binding assay. On admission to the study this patient had predominantly ring (immature trophozoite) stage parasites (a). Following a period of in vitro culture the parasites matured, in this case to late trophozoite stages, as required for the static binding assay (b). Infected erythrocytes bound to an ICAM-1 coated area of the assay dish are marked with arrows (c).

Static protein binding assays

A method adapted from McCormick et al.[9] to test the ability of infected erythrocytes to bind to purified recombinant human Fc chimera ICAM-1, VCAM, and CD36 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, USA) was used. Three identical areas of each Petri dish (60 mm diameter, product code 351007, Becton, Dickenson and Company, NJ, USA) were treated with 2 μl aliquots of purified ICAM-1, VCAM, CD36, each at 100 μg/mL. Control areas were treated with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and three marked areas were left untreated. The dishes were incubated in a humid chamber at 37°C for two hours before aspirating off excess protein and blocking all areas with 1% w/v bovine serum albumin in PBS for 2 h at 37°C. The blocking solution was removed by gentle pipetting. Ex vivo matured infected erythrocyte cultures were added to 3 ml warmed binding buffer (RPMI 1640 media supplemented with D-glucose) to a final haematocrit of 3%. Each protein and the PBS control were represented in triplicate per dish and duplicate dishes were seeded per patient isolate. Therefore there were six replicate areas per protein or PBS control for each patient sample assayed. Dishes were seeded with 1.5 ml of the prepared ex vivo cultured cell suspension per patient isolate and a third assay dish with P. falciparum clone HB3 as an assay performance control.

The dishes were incubated at 37°C for 1 h, with gentle mixing at 10 min intervals. Unbound cells were removed by gentle washing seven times with RPMI 1640 supplemented with D-glucose. Bound cells were fixed with 1% v/v gluteraldehyde for 1 h and stained with 10% Giemsa. For example see Figure 1c. Using an inverted light microscope at × 300 magnification images from ten consecutive non-overlapping fields for each protein and PBS treated area (six areas each per patient sample) were captured. This was equivalent to an area of 0.135 mm2. The number of bound infected cells/0.135 mm2/protein or control were counted. The results were expressed as the number of infected cells (IE) bound/mm2 to each of the proteins or control [IE/mm2 = (1/0.0135) × mean number of bound IE per field]. Significant binding of P. falciparum clone HB3 to all three test proteins compared with PBS was required in the assay performance control to validate the results for each patient isolate. Purified protein binding assays on primary field isolates are quantifiable within but not between isolates because of variability in parasitaemia. Significant binding to each protein compared with binding to PBS was determined using the Mann-Whitney U Test (Graphpad PRISM version 4.0a San Diego California, USA).

Results

Five patients with PCR confirmed single species P. knowlesi infections were recruited into the study. Parasitaemia ranged from 0.4 to 7%. Clinical and parasitological data are summarised in Table 1. Apart from patient (P0009) with high parasitaemia and renal failure the patients had acute uncomplicated malaria. Blood samples were cultured ex vivo for up to 14.5 h (mean 11.3 ± 1.9 h) to allow parasite maturation and increase the relative proportion of mature trophozoite and schizont-infected red blood cells to at least 50% (mean 65.8 ± 17.51%) of all parasite stages present in preparation for binding assays (Table 1).

Binding to ICAM-1, VCAM and CD36

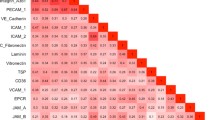

Three (60%) isolates bound significantly to ICAM-1 and VCAM. One (20%) isolate bound significantly to VCAM and one isolate did not bind significantly to ICAM-1, VCAM or CD36 (Figure 2). None of the P. knowlesi isolates tested showed significant binding to CD36 (Figure 2). The performance of each binding assay was monitored using P. falciparum clone HB3. Clone HB3 significantly bound to ICAM-1, VCAM and CD36 in all assay plates and clone HB3 binding characteristics are summarised in Figure 2.

Infected red cell binding (IRBC) to purified ICAM-1, VCAM and CD36 compared with binding to intra assay PBS controls for P. knowlesi infected patients P0002, P0006, P0009. P0010 and P0011. The median and inter quartile range (IQR) of six replicates per protein or PBS control per isolated are shown. The performance character of the assay is represented by P. falciparum clone HB3 showing the median (IQR) binding of all control assays (15 replicates per protein and PBS). Significance of binding was analaysed using the Mann-Whitney U test comparing specific binding of IRBC/mm2 to each purified protein with intra assay binding to PBS control areas: * p = < 0.05; ** p = < 0.01; ***p = < 0.0001.

Discussion

Plasmodium knowlesi infected erythrocytes from human infections bind in a specific but variable manner to the human endothelial cell receptors ICAM-1 and VCAM but not to CD36. Specific binding of infected erythrocytes to endothelial cell receptors is responsible for cytoadherence and, therefore, sequestration of late trophozoite and schizont infected erythrocytes from the peripheral blood circulation in P. falciparum malaria [6]. With few exceptions only immature trophozoite stages of P. falciparum infected erythrocytes are found in the circulation of patients with acute uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Plasmodium falciparum PfEMP1 proteins predominantly bind to CD36, a constitutively expressed scavenger pattern recognition protein, and variably to ICAM-1 and other up-regulated endothelial cell receptors [8, 9, 20, 21]. CD36 is not expressed on areas of brain endothelium where cytoadherence occurs [22] and binding to ICAM-1 on brain endothelium is implicated in the pathophysiology of severe falciparum malaria with coma [8, 9, 20]. Particular expression of PfEMP1 variants, with differential ability to bind ICAM-1, has been demonstrated in malaria patients with coma [22, 23]. Parasite sequestration through cytoadherence in P. falciparum infections can be organ specific but it is not clear yet whether this equates with virulence rather than with available binding sites and parasite binding affinity [20, 21, 24, 25]. There is some data to suggest stratification of the var type early in infection and it has been suggested that cytoadherence to available receptors is responsible for this [26]. Mature stage parasites are observed in the circulation of all other types of malaria of humans, including P. knowlesi malaria. However, this does not exclude the possibility of a degree of parasite sequestration by specific binding to endothelial cell receptors or by other means. ICAM-1 is expressed in low copy number in resting endothelium and is up-regulated in inflammation and infection [25, 27, 28] including severe malaria with coma [7]. In falciparum malaria TNF has been implicated in ICAM-1 up-regulation although infected red blood cells alone are sufficient to produce this effect [25]. Plasmodium falciparum isolates from patients with differing degrees of disease severity show endothelial receptor binding diversity [29] with binding to ICAM-1 highest and most robust in P. falciparum isolates from patients with severe malaria with coma [22, 29]. Plasmodium knowlesi proteins expressed on infected erythrocytes do not appear to bind to CD36 is this study. This lack of adhesion in a robust manner to constitutively expressed abundant endothelial receptors, such as CD36, would explain the presence of mature stage parasites in the circulation when inducible target receptors are not up-regulated. Significant but variable binding of P. knowlesi infected erythrocytes from human infections to the inducible endothelial receptors ICAM-1 and VCAM was demonstrated here. This result suggests that, if up-regulated on brain endothelium, P. knowlesi infected erythrocytes could potentially cytoadhere to ICAM-1 in that compartment. Notwithstanding this possibility, immunohistochemistry failed to detect ICAM-1 on the endothelial surfaces in parasite congested brain sections of a fatal case of severe knowlesi malaria without coma [14]. There may be technical explanations for the failure to detect ICAM-1 including limited available sections, delayed post-mortem sampling and loss of tissue integrity. It is also possible that ICAM-1 is not induced on brain endothelium in knowlesi infections and that specific binding ex vivo is not associated with parasite virulence in this species. The intense accumulation of infected erythrocytes observed in brain sections in fatal knowlesi malaria may have occurred through processes other than specific cytoadherence, for example infected cell agglutination [15]. This study and clinical descriptions of severe and fatal knowlesi malaria suggest that up-regulation of ICAM-1 observed in P. falciparum infections is less evident in P. knowlesi malaria and that direct or indirect induction of ICAM-1 may be a defining Plasmodium species-specific virulence factor in severe malaria with coma.

Conclusions

In summary, P. knowlesi infected erythrocytes from human subjects can bind to the inducible endothelial receptors ICAM-1 and VCAM. Further work will be required to define the pathological implication of these interactions.

References

Brewster DR, Kwiatkowski D, White NJ: Neurological sequelae of cerebral malaria in children. Lancet. 1990, 336: 1039-1043. 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92498-7.

Mishra SK, Wiese L: Advances in the management of cerebral malaria in adults. Curr Opin Neurol. 2009, 22: 302-307. 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32832a323d.

Aikawa M, Iseki M, Barnwell JW, Taylor D, Oo MM, Howard RJ: The pathology of human cerebral malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1990, 43: 30-37.

Silamut K, Phu NH, Whitty C, Turner GD, Louwrier K, Mai NT, Simpson JA, Hien TT, White NJ: A quantitative analysis of the microvascular sequestration of malaria parasites in the human brain. Am J Pathol. 1999, 155: 395-410. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65136-X.

Udomsangpetch R, Pipitaporn B, Krishna S, Angus B, Pukrittayakamee S, Bates I, Suputtamongkol Y, Kyle DE, White NJ: Antimalarial drugs reduce cytoadherence and rosetting Plasmodium falciparu. J Infect Dis. 1996, 173: 691-698. 10.1093/infdis/173.3.691.

Su XZ, Heatwole VM, Wertheimer SP, Guinet F, Herrfeldt JA, Peterson DS, Ravetch JA, Wellems TE: The large diverse gene family var encodes proteins involved in cytoadherence and antigenic variation of Plasmodium falciparu-infected erythrocytes. Cell. 1995, 82: 89-100. 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90055-1.

Turner GD, Morrison H, Jones M, Davis TME, Looareesuwan S, Buley ID, Gatter KC, Newbold CI, Pukritayakamee S, Nagachinta B, White NJ, Berendt AR: An immunohistochemical study of the pathology of fatal malaria. Evidence for widespread endothelial activation and a potential role for intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in cerebral sequestration. Am J Pathol. 1994, 145: 1057-1069.

Udomsangpetch R, Taylor BJ, Looareesuwan S, White NJ, Elliott JF, Ho M: Receptor specificity of clinical Plasmodium falciparu isolates: nonadherence to cell-bound E-selectin and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1. Blood. 1996, 88: 2754-2760.

McCormick CJ, Craig A, Roberts D, Newbold CI, Berendt AR: Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and CD36 synergize to mediate adherence of Plasmodium falciparu-infected erythrocytes to cultured human microvascular endothelial cells. J Clin Invest. 1997, 100: 2521-2529. 10.1172/JCI119794.

Berendt AR, Simmons DL, Tansey J, Newbold CI, Marsh K: Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 is an endothelial cell adhesion receptor for Plasmodium falciparu. Nature. 1989, 341: 57-59. 10.1038/341057a0.

Cox-Singh J, Davis TM, Lee KS, Shamsul SS, Matusop A, Ratnam S, Rahman HA, Conway DJ, Singh B: Plasmodium knowles malaria in humans is widely distributed and potentially life threatening. Clin Infect Dis. 2008, 46: 165-171. 10.1086/524888.

Daneshvar C, Davis TM, Cox-Singh J, Rafa'ee MZ, Zakaria SK, Divis PC, Singh B: Clinical and laboratory features of human Plasmodium knowles infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2009, 49: 852-860. 10.1086/605439.

William T, Menon J, Rajahram G, Chan L, Ma G, Donaldson S, Khoo S, Frederick C, Jelip J, Anstey NM, Yeo TW: Severe Plasmodium knowles Malaria in a Tertiary Care Hospital, Sabah, Malaysia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011, 17: 1248-1255. 10.3201/eid1707.101017.

Cox-Singh J, Hiu J, Lucas SB, Divis PC, Zulkarnaen M, Chandran P, Wong KT, Adem P, Zaki SR, Singh B, Krishna S: Severe malaria - a case of fatal Plasmodium knowles infection with post-mortem findings: a case report. Malar J. 2010, 9: 10-10.1186/1475-2875-9-10.

Howard RJ, Barnwell JW, Kao V: Antigenic variation of Plasmodium knowles malaria: identification of the variant antigen on infected erythrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983, 80: 4129-4133. 10.1073/pnas.80.13.4129.

al-Khedery B, Barnwell JW, Galinski MR: Antigenic variation in malaria: a 3' genomic alteration associated with the expression of a P. knowles variant antigen. Mol Cell. 1999, 3: 131-141. 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80304-4.

Korir CC, Galinski MR: Proteomic studies of Plasmodium knowles SICA variant antigens demonstrate their relationship with P. falciparu EMP1. Infect Genet Evol. 2006, 6: 75-79. 10.1016/j.meegid.2005.01.003.

Milner DA: Rethinking cerebral malaria pathology. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2010, 23: 456-463. 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32833c3dbe.

Singh B, Kim Sung L, Matusop A, Radhakrishnan A, Shamsul SS, Cox-Singh J, Thomas A, Conway DJ: A large focus of naturally acquired Plasmodium knowles infections in human beings. Lancet. 2004, 363: 1017-1024. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15836-4.

Udomsangpetch R, Reinhardt PH, Schollaardt T, Elliott JF, Kubes P, Ho M: Promiscuity of clinical Plasmodium falciparu isolates for multiple adhesion molecules under flow conditions. J Immunol. 1997, 158: 4358-4364.

Tse MT, Chakrabarti K, Gray C, Chitnis CE, Craig A: Divergent binding sites on intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) for variant Plasmodium falciparu isolates. Mol Microbiol. 2004, 51: 1039-1049. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03895.x.

Ochola LB, Siddondo BR, Ocholla H, Nkya S, Kimani EN, Williams TN, Makale JO, Liljander A, Urban BC, Bull PC, Szestak T, Marsh K, Craig AG: Specific receptor usage in Plasmodium falciparu cytoadherence is associated with disease outcome. PLoS One. 2011, 6: e14741-10.1371/journal.pone.0014741.

Janes JH, Wang CP, Levin-Edens E, Vigan-Womas I, Guillotte M, Melcher M, Mercereau-Puijalon O, Smith JD: Investigating the host binding signature on the Plasmodium falciparu PfEMP1 protein family. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7: e1002032-10.1371/journal.ppat.1002032.

Montgomery J, Mphande FA, Berriman M, Pain A, Rogerson SJ, Taylor TE, Molyneux ME, Craig A: Differential var gene expression in the organs of patients dying of falciparum malaria. Mol Microbiol. 2007, 65: 959-967. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05837.x.

Wu Y, Szestak T, Stins M, Craig AG: Amplification of P. falciparu cytoadherence through induction of a pro-adhesive state in host endothelium. PLoS One. 2011, 6: e24784-10.1371/journal.pone.0024784.

Lavstsen T, Magistrado P, Hermsen CC, Salanti A, Jensen AT, Sauerwein R, Hviid L, Theander TG, Staalsoe T: Expression of Plasmodium falciparu erythrocyte membrane protein 1 in experimentally infected humans. Malar J. 2005, 4: 21-10.1186/1475-2875-4-21.

McGuire W, Hill AV, Greenwood BM, Kwiatkowski D: Circulating ICAM-1 levels in falciparum malaria are high but unrelated to disease severity. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1996, 90: 274-276. 10.1016/S0035-9203(96)90244-8.

Turner GD, Ly VC, Nguyen TH, Tran TH, Nguyen HP, Bethell D, Wyllie S, Louwrier K, Fox SB, Gatter KC, Day NP, Tran TH, White NJ, Berendt AR: Systemic endothelial activation occurs in both mild and severe malaria. Correlating dermal microvascular endothelial cell phenotype and soluble cell adhesion molecules with disease severity. Am J Pathol. 1998, 152: 1477-1487.

Newbold C, Warn P, Black G, Berendt A, Craig A, Snow B, Msobo M, Peshu N, Marsh K: Receptor-specific adhesion and clinical disease in Plasmodium falciparu. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997, 57: 389-398.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of staff at Hospital Sarikei especially Mr Wong Ching Toh, Mr Pek Peng Chin. Mdm Siti Syartinah and Mdm Raymand Johan for helping with patient recruitment. Puan Dyang and the staff at the Malaria Research Centre at UNIMAS. We would also like to thank the training provided by Mr Tadge Szestak at LSTM and Dr Henry M Staines for use of equipment and discussions. Finally, we would like to thank the patients who so kindly agreed to be a part of this study, and without whom this research would not have been possible. This study was funded by the Medical Research Council (MRC) UK; Grant number G0801971. FAF was funded by the MRC-Doctoral Training Grant G0800110.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

The study was conceived by JCS and designed by JCS, AGC, SK and BS. The assays were performed by FAF with field support from AS, MAH and LCW. The manuscript was prepared by JCS, ACG, and SK. All authors had the opportunity to read and approve the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Fatih, F.A., Siner, A., Ahmed, A. et al. Cytoadherence and virulence - the case of Plasmodium knowlesi malaria. Malar J 11, 33 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-11-33

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-11-33