Abstract

Background

The reemergence of Plasmodium vivax in South Korea since 1993 represents a serious public health concern. Despite the importance in understanding genetic diversity for control strategies, however, studies remain inconclusive with the general premise that due to low rate of malaria transmission, there is generally low genetic diversity with very few strains involved. In this study, the genetic diversity and population structure of P. vivax in South Korea were explored by analysing microsatellite polymorphism.

Methods

Sequences for 13 microsatellite loci distributed across the twelve chromosomes of P. vivax were obtained from 58 South Korean isolates collected during two sampling periods, namely 1997-2000 and 2007. The sequences were used for the analysis of expected heterozygosity and multilocus genotype diversity. Population structure was evaluated using STRUCTURE version 2.3.2. Linkage disequilibrium was also analysed to investigate the extent of outbreeding in the P. vivax population.

Results

Mean expected heterozygosity significantly increased from 0.382 in 1997-2000 to 0.545 in 2007 (P < 0.05). The number of multilocus genotypes was 7 and 27; and genotype diversity was statistically significant (P < 0.01) at 0.661 and 0.995 in 1997-2000 and 2007, respectively. Analysis by STRUCTURE showed a more complex population structure in 2007 than in 1997-2000. Linkage disequilibrium between 13 microsatellites, although significant in both time points, was notably lower in 2007.

Conclusions

The present microsatellite analysis clearly showed recent increase of genetic diversity and recent relaxation of the strong population structure observed in 1997-2000. These results suggest that multiple genotypes not present previously recently migrated into South Korea, accompanied by substantial outbreeding between different genotypes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Of the five human malaria parasites, Plasmodium vivax is the most prevalent in Asia, Melanesia, the Middle East, South and Central America, accounting for 70-80 million cases annually [1], with 2.6 billion people at risk of infection [2]. Despite modest gains in Plasmodium falciparum control, the global burden of P. vivax remains underestimated [3] and emergence of drug resistant P. vivax makes the control of vivax malaria more difficult than before [4, 5]. In the Republic of Korea (South Korea), vivax malaria was eradicated once in the late 1970s [6]. However, indigenous malaria has reemerged since the first infection of a soldier who had never been abroad was confirmed in 1993 in the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) between South and North Korea [7]. Thereafter, vivax malaria infection has spread to civilians and the number of cases from 2000 has fluctuated between 864 and 4,142 [8]. Thus, vivax malaria has become endemic again and constitutes a serious public concern in South Korea. Meanwhile, in North Korea, vivax malaria is more prevalent than in South Korea and the number of cases has fluctuated between 7,436 and 296,540 from 2000 [6, 9].

Genetic diversity and population structure of P. vivax have a significant impact on malaria transmission, spread of drug-resistance and the acquisition of protective immunity against malaria. Studies of the parasite population diversity have practical significance for the strategic development and deployment of control measures [10]. Limited studies on antigen-encoding genes such as merozoite surface protein-1 (MSP-1), circumsporozoite surface protein (CSP) and merozoite surface protein-3α (MSP-3α) in South Korea have previously shown that the diversity of those genes was low in 1990s, but increased after 2000 [9, 11]. An increase in antigen diversity potentially affects the acquisition of protective immunity against vivax malaria. It is therefore important to determine whether the observed recent increase of the diversity of antigen-encoding genes is caused by human immune pressure or not. Since these antigens are exposed to the human immune system, diversity in the antigen-encoding loci can be attributed to not only to natural selection by immune pressure but also to the parasite's population history [12]. Hence, it remains uncertain whether the low diversity observed in the antigen-encoding loci resulted from selective pressure imposed by the host immune system or due to a demographic change in the local parasite population. In contrast to polymorphic antigen genes, microsatellite markers are selectively neutral and highly polymorphic, and, thus, are suitable for the assessment of genetic diversity resulting from demography at the genome-wide level. Recently, microsatellite markers have been widely used to analyse genetic diversity of P. vivax populations [13–18]. In the present study, multilocus microsatellite analysis was conducted to elucidate genetic diversity and population structure of P. vivax in South Korea. Results showed drastic changes in genetic diversity and population structure between 2000 and 2007.

Methods

Parasite samples

Blood samples were collected from indigenous P. vivax-infected patients between 1996 and 2007 near the DMZ in the Republic of Korea [9]. In this study, two groups classified according to the sampling year were analysed: one group of 29 samples collected between 1997 and 2000, and the other from 29 samples collected in 2007. Informed consent was obtained from all patients before blood sampling. The study was approved by Korea's National Institute of Health, and Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Preparation of parasite DNA

Plasmodium vivax DNA were extracted from 200 μL blood using proteinase K digestion technique and followed either by purification with phenol-chloroform or QIAamp® DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer's instructions.

PCR and sequencing analysis for genotyping

Thirteen validated polymorphic microsatellite markers, 1.501, 3.27, 3.502, MS3, MS15, MS5, MS9, MS16, MS20, MS6, MS8, MS10 and 14.297 [15, 19], distributed across the twelve chromosomes of P. vivax (Additional file 1) were used for analysis. Microsatellites were sequenced to achieve higher-resolution analysis rather than the widely employed fragment-length measurements. Besides, P. vivax microsatellites used in this study contain relatively long and somewhat degenerating repeating units, which cannot be satisfactorily assessed by fragment-length measurements. For example, in MS20 two alleles observed with the same length, (GAA)5(CAA)3 and (GAA)6(CAA)2, would be indistinguishable from each other by fragment-length measurement. Primers for each locus were newly designed in order to perform polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and subsequent sequencing (Additional file 1). PCR reactions were performed in 20 μL reaction mixture containing 1× LA PCR™ Buffer, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.4 mM dNTP, 0.2 μM of each primer solution, 0.05 U LA Taq® (Takara Bio Inc.) and 1 μL DNA template. The reaction protocol was as follows: 1 cycle at 93°C for 1 min; 40 cycles at 93°C for 20 s, 62°C for 4 min; and 1 cycle at 72°C for 10 min. The nucleotide sequence of each locus was determined directly from the PCR products using BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems) on an Applied Biosystems 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) following the manufacturer's instructions. An allele for each locus corresponds to the number of repeat-motifs. Genotype is defined as the unique combination of alleles across the 13 microsatellite loci examined for this study.

Data analysis

Expected heterozygosity (hE) of each locus was calculated by using the formula hE = {n/(n-1)}(1-∑pi2), where n is the number of isolates analysed and pi is the frequency of the ith allele in the population. Variance (V) of hE was calculated by using the formula V = 2/{n(n-1)}[a+b], where a = 2(n-2){∑pi3-(∑pi2)2} and b = ∑pi2-(∑pi2)2 [20]. The standard error (SE) of hE was defined as the square root of V. Mean expected heterozygosity (HE) of all loci and the standard error were also calculated. The statistical significance of the mean differences between expected heterozygosity values was determined by t-test as described by Nei, 1987 [21]. Genotype diversity (gd) was calculated similar to expected heterozygosity.

The standardized index of association (IS A ) was calculated to test the presence of overall multilocus linkage disequilibrium [22]. This test compares the variance (V D ) of the number of alleles shared between all pairs of haplotypes observed in the population (D) with the variance expected under random association of alleles (V E ) as follows: IS A = (V D /V E -1)/(r-1), where r is the number of loci analysed. V E is derived from 100,000 simulated data sets in which alleles were randomly reshuffled among haplotypes. Linkage disequilibrium (LD) is significant if V D is > 95% of the values derived from the reshuffled data sets. Data were analysed using LIAN version 3.5 software [23]. LD for all pairs of loci was also tested using the Genepop version 4.1 [24] under the following Markov chain parameters: dememorization number = 20,000, number of batches = 500 and number of iterations per batch = 10,000.

Population structure was evaluated using the STRUCTURE version 2.3.2 software [25]. This Bayesian model-based clustering method assigns samples to K populations according to allele frequencies of each locus. The program was run 20 times at each of 10 different K values (1-10) with a period of 50,000 burn-in steps followed by 100,000 iterations. The admixture model with independent allele frequencies was used in all analyses. The number of populations was inferred by plotting the log probability of the data [Ln P(D)] for each K value. Also, in order to determine the most appropriate number of K, ΔK was calculated as described by Evanno et al [26]. Illustrations were generated using the DISTRUCT program [27].

Results

Genetic diversity

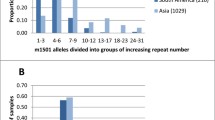

Microsatellite sequences from 29 isolates in 1997-2000 (Group 1) and another 29 in 2007 (Group 2) were obtained in this study (n = 58 isolates in total). There were two cases in the 1997-2000 group where three sequences could not be obtained. All microsatellite loci were polymorphic, exhibiting three to six alleles per locus (Table 1 and Additional file 2). The total number of alleles detected was 60 in the two groups and the number increased from 33 in 1997-2000 to 50 in 2007. Of the 60 alleles, 23 alleles were found in both sampling periods, while 10 and 27 alleles were unique in 1997-2000 and in 2007, respectively, suggesting drastic change in microsatellite alleles between 1997-2000 and 2007. In eight loci, the number of alleles increased in 2007, and in other loci frequency remained similar with one exception, locus 1.501, where allele number was low in 2007 as compared to 1997-2000. Expected heterozygosity (hE) for each locus ranged from 0.069 to 0.548 for 1997-2000, and from 0.133 to 0.778 for 2007 (Table 1). All the loci, except 1.501 and MS9, showed higher hE in 2007 than in 1997-2000. These exceptions underscore the importance of using several markers to characterize genetic diversity of a population. Mean expected heterozygosity (HE) was 0.382 ± 0.061 and 0.545 ± 0.063 in 1997-2000 and 2007, respectively (Table 1). The difference between the two sampling periods was statistically significant (P = 0.023), indicating a recent increase in the genetic diversity of the P. vivax population in South Korea.

A total of 33 multilocus genotypes, which were defined as the unique association of alleles in the 13 microsatellite loci, were detected: seven in 1997-2000 and 27 in 2007 with one genotype (no. 25) found in both groups (Table 2). Two of the seven genotypes (no. 25 and 30) comprised 81.5% (22/27) in 1997-2000. Remarkably, for 2007, most genotypes were found only once, except for no. 7 and 8. These suggest a drastic change in genetic diversity between the two groups. Genotype diversity (gd) was 0.661 ± 0.005 for 1997-2000, and 0.995 ± 0.000 for 2007 (P = 0.00004). Hence, the diversity of multilocus genotypes appears to have significantly increased between 2000 and 2007.

Linkage disequilibrium

The overall multilocus linkage disequilibrium assessed by LIAN showed significant LD in 1997-2000 and 2007. LD was stronger in earlier than in recent sampling period: IS A = 0.5565, P < 0.001 for 1997-2000 and IS A = 0.1813, P < 0.001 for 2007. Linkage disequilibrium for each pair of microsatellite loci by Genepop further supported the difference between 1997-2000 and 2007. LD was significant in 70 pairs of the 78 possible pairs (90%) for 1997-2000, while it was significant in 33 of all possible pairs (42%) for 2007 (Figure 1). The microsatellite loci used in this study were located on different chromosomes, other than 3.27 and 3.502, which are both located on chromosome 3, separated by 42 kilobases. These results, thus, indicate that the genetic shuffling of different chromosomes occurred rarely during sexual reproduction in the mosquito vector in 1997-2000, while it was substantial in 2007, suggesting a high level of inbreeding in 1997-2000 and substantial outbreeding in 2007. Strong linkage disequilibrium observed between 3.27 and 3.502 indicate that meiotic recombination did not occur between these loci in the same chromosome in 1997-2000 and 2007.

Assignment analysis to infer population structure

Analysis by STRUCTURE is shown in Figure 2. The highest Ln P(D) which suggests the strongest statistical support was observed at K = 5 (Figure 2A). The most appropriate estimate of K, the highest ΔK, was observed at K = 3 (Figure 2B). For these reasons, these two K values were adopted. In Figures 2C and 2D, an individual isolate is represented by each vertical bar, in which segments (represented by colours) are proportionally partitioned according to the estimated membership fraction assigned to K clusters. In both K values, population was highly distinctive between 1997-2000 and 2007. Isolates from 1997-2000 were mainly derived from two populations, with a majority of isolates assigned to a single cluster. These indicate strong population structure in 1997-2000 and suggest that outbreeding between different populations rarely occurred. Clustering patterns at K = 5 (but not K = 3) suggests that isolate no. 6 in 1997-2000 was a clearly distinct from others. Isolates from 2007 were mainly derived from three clusters at K = 3 and four clusters at K = 5. Of note, one cluster at K = 3 (shown in orange) and two clusters at K = 5 (shown by red and orange colours) predominated in 2007, but were rare in 1997-2000. Clusters that predominated in 1997-2000 were minor in 2007. Some isolates in 2007 (e.g., no. 1, 3, 8 and 10) were assigned to multiple clusters (Figure 2D), which composed those clusters that predominated in 1997-2000 and those that newly appeared in 2007. These results indicate that a dramatic change occurred in the P. vivax population structure: the strong population structure found in 1997-2000 was relaxed and became more complex in 2007; and, likewise, substantial outbreeding among different parasite genotypes in 2007 is suggested.

Drastic change in the population structure of P. vivax between 1997-2000 and 2007. The population structure of P. vivax in the Republic of Korea was inferred using STRUCTURE analysis and plots were drawn using DISTRUCT. (A) Plot of log probability of data [Ln P(D)] against the number of populations tested (K). (B) Plot of ΔK (the rate of change in the log probability of the data between successive K values) against the number of K. An individual parasite isolate is represented by a single vertical bar, which is partitioned into three (C) or five (D) segments. Sample numbers are shown along the horizontal axes. Each segment represents one population, and the colour of the segment represents the estimated membership fraction in the individual parasite assigned to K clusters.

Discussion

This study is the first to report microsatellite diversity of the P. vivax population in South Korea. The present results obtained with 13 microsatellite markers across 12 chromosomes revealed a higher genetic diversity in 2007 than in 1997-2000. Consistent with previous limited studies showing a recent increase in antigen diversity, the study further support changes in P. vivax isolates from South Korea. Analysis of South Korean isolates before 2000 using antigen-encoding genes such as Duffy-binding protein [28], PvCSP [9], PvMSP-3α [11], and AMA-1 [29] infers only two alleles whereas genetic diversity of these antigens remarkably increased after 2001 [9, 11]. The present study shows only two major multilocus microsatellite genotypes that comprise the two major P. vivax populations in 1997-2000, while numerous genotypes appeared in 2007. It is surmised that the recent increase in P. vivax genetic diversity was displayed at the genome wide level, and suggest that increased antigen diversity was not driven, if any, by selective pressure on antigen genes. While it is of note that the P. vivax genetic diversity in South Korea has increased in recent years (HE = 0.55 in 2007), diversity is still low as compared to levels obtained from other geographic areas with the exception of Peru: thus, HE = 0.71-0.86 in Brazil, Colombia, India, Laos, Thailand, Sri Lanka, Vietnam, Ethiopia, and Myanmar [13–15, 17, 19], vs HE = 0.44 - 0.69 in Peru (Table 3) [18]. However, although the South Korean P. vivax populations appear to have relatively low genetic diversity, direct comparisons of HE with other parasite populations from different geographical areas must be treated with caution especially when the number of samples used is substantially different. In this study, sample number is somewhat small (n = 58) as compared with other geographical areas (e.g., 159 in Peru [18]; 140, 167 and 118 in Sri Lanka, Myanmar and Ethiopia, respectively [14]). Further investigations using more samples should be performed to confirm a low genetic diversity in P. vivax population in South Korea.

Two mechanisms can be proposed to account for the observed increase in the genetic diversity of P. vivax population in South Korea. One is the accumulation of microsatellite mutations in the population, and the other is migration of novel parasite populations from other geographic areas into South Korea. Since the mutation rate(s) of P. vivax microsatellite is unknown, accumulation of mutation cannot be completely excluded. However, the present study does reveal the appearance of very many novel alleles at almost all the microsatellite loci examined. Previous studies have also reported rapid increase in genetic diversity in antigen-encoding genes [9, 11]. It is very unlikely that in a short period (between 2000 and 2007, probably six generations of the parasite life cycle in South Korea), many novel alleles accumulate simultaneously at several microsatellite and antigen loci. The idea of migration of multiple different parasite genotypes from other geographic areas into South Korea is, therefore, favoured. Haplotype network analysis based on the parasite mitochondrial genome infers a genealogical origin in southern China for P. vivax populations collected in 1999 and one in 2002 [30]. Further investigations on genetic diversity of P. vivax in neighbouring geographic areas can elucidate and verify the population mechanism.

The rate of inbreeding also contributes to the extent of genetic diversity in P. vivax populations. In this study, the extent of inbreeding inferred from linkage disequilibrium was reduced in 2007, compared with that in 1997-2000; although overall linkage disequilibrium was significant in both sampling groups. These results indicate very strong linkage disequilibrium, leading to a high inbreeding rate in the parasite population in 1997-2000, whereas relatively weak linkage disequilibrium, leading to elevation of outbreeding levels in 2007. Analysis by STRUCTURE (Figure 2C and 2D) supports the increased outbreeding in 2007. It is thus concluded that the recent diversification of South Korean P. vivax population resulted partly from an increase in the level of outbreeding among different parasite genotypes.

Moving forward, molecular tools and techniques can elucidate parasite genetic diversity and population structure that can help malaria control efforts and understand mechanisms of pathogenicity and drug resistance. It is generally believed in a parasite population with a high genetic diversity, protective immunity against malaria is slow to develop. There is accumulating evidence, which suggest that P. vivax is more virulent than previously thought in tropical endemic areas [5], where genetic diversity is generally high (Table 3). This raises the potential risk of severe malaria in South Korea if genetic diversity further increase to a level observed in tropical endemic areas. Recently, drug-resistant P. vivax has been reported in South Korea [31], which emphasizes increasing importance of assessing genetic diversity and population structure in this area. Since results obtained in this study strongly suggest an increase in the genetic diversity of P. vivax population in South Korea, monitoring of the parasite genetic diversity in this country as well as in neighbouring endemic areas will provide valuable information for developing malaria control strategies in South Korea.

Conclusions

The present microsatellite analysis showed a recent expansion in the genome-wide genetic diversity of the P. vivax population in South Korea. This expansion is suggested to be due to recent migrations of different genotypes from other geographic areas into South Korea. Drastic change of P. vivax population structure during the period was also detected, in which a substantial increase in outbreeding partly contributes to the increased genetic diversity. Compared with genetic diversity in P. vivax populations from other geographic areas, the genetic diversity in South Korea is still low, although significant increase has been noted in recent years. This suggests that control of vivax malaria in this country could be achieved in line with WHO's agenda for malaria eradication.

References

Mendis K, Sina BJ, Marchesini P, Carter R: The neglected burden of Plasmodium vivax malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001, 64: 97-106.

Guerra CA, Snow RW, Hay SI: Mapping the global extent of malaria in 2005. Trends Parasitol. 2006, 22: 353-358. 10.1016/j.pt.2006.06.006.

World Health Organization: World Malaria Report 2010. 2010, [http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241564106_eng.pdf]

Baird JK, Schwartz E, Hoffman SL: Prevention and treatment of vivax malaria. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2007, 9: 39-46. 10.1007/s11908-007-0021-4.

Price RN, Douglas NM, Anstey NM: New developments in Plasmodium vivax malaria: severe disease and the rise of chloroquine resistance. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2009, 22: 430-435. 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32832f14c1.

Chai JY: Re-emerging Plasmodium vivax malaria in the Republic of Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 1999, 37: 129-143. 10.3347/kjp.1999.37.3.129.

Chai IH, Lim GI, Yoon SN, Oh WI, Kim SJ, Chai JY: Occurrence of tertian malaria in a male patient who has never been abroad. Korean J Parasitol. 1994, 32: 195-200. 10.3347/kjp.1994.32.3.195.

Park J, Jun G, Yeom J: Plasmodium vivax malaria: status in the Republic of Korea following reemergence. Korean J Parasitol. 2009, 47 (Suppl): S39-50. 10.3347/kjp.2009.47.S.S39.

Choi YK, Choi KM, Park MH, Lee EG, Kim YJ, Lee BC, Cho SH, Rhie HG, Lee HS, Yu JR, Lee JS, Kim TS, Kim JY: Rapid dissemination of newly introduced Plasmodium vivax genotypes in South Korea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010, 82: 426-432. 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0245.

Cui L, Escalante AA, Imwong M, Snounou G: The genetic diversity of Plasmodium vivax populations. Trends Parasitol. 2003, 19: 220-226. 10.1016/S1471-4922(03)00085-0.

Nam DH, Oh JS, Nam MH, Park HC, Lim CS, Lee WJ, Sattabongkot J, Klein TA, Ayala FJ: Emergence of new alleles of the MSP-3α gene in Plasmodium vivax isolates from Korea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010, 82: 522-524. 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.08-0332.

Escalante AA, Cornejo OE, Rojas A, Udhayakumar V, Lal AA: Assessing the effect of natural selection in malaria parasites. Trends Parasitol. 2004, 20: 388-395. 10.1016/j.pt.2004.06.002.

Ferreira MU, Karunaweera ND, da Silva-Nunes M, da Silva NS, Wirth DF, Hartl DL: Population structure and transmission dynamics of Plasmodium vivax in rural Amazonia. J Infect Dis. 2007, 195: 1218-1226. 10.1086/512685.

Gunawardena S, Karunaweera ND, Ferreira MU, Phone-Kyaw M, Pollack RJ, Alifrangis M, Rajakaruna RS, Konradsen F, Amerasinghe PH, Schousboe ML, Galappaththy GN, Abeyasinghe RR, Hartl DL, Wirth DF: Geographic structure of Plasmodium vivax: microsatellite analysis of parasite populations from Sri Lanka, Myanmar, and Ethiopia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010, 82: 235-242. 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0588.

Imwong M, Nair S, Pukrittayakamee S, Sudimack D, Williams JT, Mayxay M, Newton PN, Kim JR, Nandy A, Osorio L, Carlton JM, White NJ, Day NP, Anderson TJ: Contrasting genetic structure in Plasmodium vivax populations from Asia and South America. Int J Parasitol. 2007, 37: 1013-1022. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2007.02.010.

Karunaweera ND, Ferreira MU, Munasinghe A, Barnwell JW, Collins WE, King CL, Kawamoto F, Hartl DL, Wirth DF: Extensive microsatellite diversity in the human malaria parasite Plasmodium vivax. Gene. 2008, 410: 105-112. 10.1016/j.gene.2007.11.022.

Van den Eede P, Erhart A, Van der Auwera G, Van Overmeir C, Thang ND, Hung l, Anné J, D'Alessandro U: High complexity of Plasmodium vivax infections in symptomatic patients from a rural community in central Vietnam detected by microsatellite genotyping. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010, 82: 223-227. 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0458.

Van den Eede P, Van der Auwera G, Delgado C, Huyse T, Soto-Calle VE, Gamboa D, Grande T, Rodriguez H, Llanos A, Anné J, Erhart A, D'Alessandro U: Multilocus genotyping reveals high heterogeneity and strong local population structure of the Plasmodium vivax population in the Peruvian Amazon. Malar J. 2010, 9: 151-10.1186/1475-2875-9-151.

Karunaweera N, Ferreira MU, Hartl DL, Wirth D: Fourteen polymorphic microsatellite DNA markers for the human malaria parasite Plasmodium vivax. Mol Ecol Notes. 2007, 7: 172-175.

Sakihama N, Ohmae H, Bakote'e B, Kawabata M, Hirayama K, Tanabe K: Limited allelic diversity of Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 1 gene from populations in the Solomon Islands. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006, 74: 31-40.

Nei M: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics. New York. 1987, Colombia University press

Hudson R: Analytical results concerning linkage disequilibrium in models with genetic-transformation and conjugation. J Evol Biol. 1994, 7: 535-548. 10.1046/j.1420-9101.1994.7050535.x.

Haubold B, Hudson RR: LIAN 3.0: detecting linkage disequilibrium in multilocus data. Linkage Analysis. Bioinformatics. 2000, 16: 847-8. 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.9.847.

Raymond M, Rousset F: GENEPOP (version 1.2): population-genetics software for exact tests and ecumenicism. J Hered. 1995, 86: 248-249.

Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P: Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000, 155: 945-959.

Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J: Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol Ecol. 2005, 14: 2611-2620. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02553.x.

Rosenberg N: DISTRUCT: a program for the graphical display of population structure. Mol Ecol Notes. 2004, 4: 137-138.

Kho WG, Chung JY, Sim EJ, Kim DW, Chung WC: Analysis of polymorphic regions of Plasmodium vivax Duffy binding protein of Korean isolates. Korean J Parasitol. 2001, 39: 143-50. 10.3347/kjp.2001.39.2.143.

Chung JY, Chun EH, Chun JH, Kho WG: Analysis of the Plasmodium vivax apical membrane antigen-1 gene from re-emerging Korean isolates. Parasitol Res. 2003, 90: 325-329. 10.1007/s00436-002-0777-2.

Iwagami M, Hwang SY, Fukumoto M, Hayakawa T, Tanabe K, Kim SH, Kho WG, Kano S: Geographical origin of Plasmodium vivax in the Republic of Korea: haplotype network analysis based on the parasite's mitochondrial genome. Malar J. 2010, 9: 184-10.1186/1475-2875-9-184.

Lee KS, Kim TH, Kim ES, Lim HS, Yeom J, Jun G, Park J: Short report: chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium vivax in the Republic of Korea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009, 80: 215-217.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Grant-in-Aids for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Sciences (JSPS) (20390120, 23590498 and 23659211) and intramural grant from Korea NIH (4837-302-210-13).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

HH performed experiments, data analyses and paper writing. JYK and WL coordinated the sampling. NMQP, TM, JYK and TH critically reviewed the manuscript. TM, JYK, WL and KT participated in acquisition of funding. KT made substantial contributions to conceive the study design, paper writing and reviewing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12936_2011_1838_MOESM1_ESM.PDF

Additional file 1: Primers for PCR and sequencing of 13 microsatellite loci of P. vivax. Primer sequences for PCR amplification and direct sequencing of microsatellite loci are detailed. Forward and reverse primers are designated with "F" or "R", respectively. (PDF 60 KB)

12936_2011_1838_MOESM2_ESM.PDF

Additional file 2: Allele frequency in 13 microsatellite loci of P. vivax populations in South Korea. The alleles for each locus and their frequencies in two sample groups are presented. An allele for each locus corresponds to the number of repeat-motifs. (PDF 56 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Honma, H., Kim, JY., Palacpac, N.M. et al. Recent increase of genetic diversity in Plasmodium vivax population in the Republic of Korea. Malar J 10, 257 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-10-257

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-10-257