Abstract

Background

Mosquito age and species identification is a crucial determinant of the efficacy of vector control programmes. Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) has previously been applied successfully to rapidly, non-destructively, and simultaneously determine the age and species of freshly anesthetized African malaria vectors from the Anopheles gambiae s.l. species complex: An. gambiae s. s. and Anopheles arabiensis. However, this has only been achieved on freshly-collected specimens and future applications will require samples to be preserved between field collections and scanning by NIRS. In this study, a sample preservation method (RNAlater®) was evaluated for mosquito age and species identification by NIRS against scans of fresh samples.

Methods

Two strains of An. gambiae s.s. (CDC and G3) and two strains of An. arabiensis (Dongola, KGB) were reared in the laboratory while the third strain of An. arabiensis (Ifakara) was reared in a semi-field system. All mosquitoes were scanned when fresh and rescanned after preservation in RNAlater® for several weeks. Age and species identification was determined using a cross-validation.

Results

The mean accuracy obtained for predicting the age of young (<7 days) or old (≥ 7 days) of all fresh (n = 633) and all preserved (n = 691) mosquito samples using the cross-validation technique was 83% and 90%, respectively. For species identification, accuracies were 82% for fresh against 80% for RNAlater® preserved. For both analyses, preserving mosquitoes in RNAlater® was associated with a highly significant reduction in the likelihood of a misclassification of mosquitoes as young or old using NIRS. Important to note is that the costs for preserving mosquito specimens with RNAlater® ranges from 3-13 cents per insect depending on the size of the tube used and the number of specimens pooled in one tube.

Conclusion

RNAlater® can be used to preserve mosquitoes for subsequent scanning and analysis by NIRS to determine their age and species with minimal costs and with accuracy similar to that achieved from fresh insects. Cold storage availability allows samples to be stored longer than a week after field collection. Further study to develop robust calibrations applicable to other strains from diverse ecological settings is recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Accurate identification of mosquito species is necessary for determining the composition of vector populations, particularly as this changes in the face of differential selective pressure exerted by vector control measures, such as insecticide-treated nets [1, 2] or indoor residual sprays [3]. These vector control measures occur mainly where morphologically indistinguishable species co-exist as vector complexes, such as Anopheles gambiae s. l., which dominates malaria transmission in most of Africa. Estimating mosquito age distribution of mosquito populations is also crucial for assessing their capacity to transmit malaria and other pathogens [4, 5]. For example, a population dominated by young mosquitoes indicates a successful vector control with ITNs and IRS interventions which reduce longevity and therefore both density and infectiousness [6, 7]. Only anophelines that are at least eleven days old can transmit malaria parasites due to the period required by the parasites to develop inside the mosquito [8], so even modest reductions of mean survival rates within vector populations can deliver substantive epidemiological impact [4, 9–11]. Assessing mosquito population age structure prior and subsequent to control interventions therefore provides a strong indication of the efficacy of that intervention.

Several techniques have been established to estimate the age of Anopheles mosquitoes. These include the traditional techniques that involve observation of the morphological changes that occur in the reproductive system of the female mosquitoes to estimate their physiological age [12–16]. Recently biochemical approaches based on age-related changes to the abundance of cuticular hydrocarbons [17] and gene transcription [18–21] have shown considerable promise although they may also be costly [22] and, therefore, have limited application for large-scale ecological or epidemiological studies. Additionally, sibling species identification within the critically important An. gambiae complex and the Anopheles funestus group from Africa relies almost exclusively upon standard Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) [23] and multiplex PCR [24, 25] protocols. These protocols are nonetheless time consuming and can be costly in a resource limited area. It is for this reason that in most cases, only a small sample of the population is tested to estimate species distribution in an area. More recently, near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) has been developed as a complimentary age grading and species identification tool for Africa's main malaria vectors An. gambiae s.s. and Anopheles arabiensis mosquitoes [26, 27]. NIRS is a rapid, non-destructive tool that can determine age and species of hundreds of mosquitoes per day. No reagents are required and only basic computer skills are needed. This NIRS technique is more cost-effective than PCR after about 7,000 samples have been analysed [26]. However, for mosquitoes, this tool has only been applied to fresh anesthetized samples, limiting its use particularly in large-scale studies where preserving samples collected under widely-dispersed sampling sites is often essential.

Current methods to preserve mosquitoes for DNA extraction or dissection include desiccation and stabilization in various storage buffers. Preservation by desiccation involves complete dehydration of samples over silica gel beads and cotton wool. Silica gel must be kept activated but is widely relied upon particularly in large-scale studies in tropical field settings for preserving mosquitoes prior to DNA and antigen assessment by PCR and ELISA techniques. For subsequent analysis of samples with NIRS however, it is also key that samples are preserved in a way that minimizes chemical degradation. Specifically, NIRS is thought to differentiate sibling species of An. gambiae s.l. (An. gambiae s.s. and An. arabiensis) based on the composition of cuticular hydrocarbons, but may also rely on water content which is known to differ between these two sibling species [28]. Additionally, age-grading of these species depends on gene transcripts [20, 21] and change of a range of other bio-molecules including cuticular hydrocarbons [17]. While desiccants are a low-cost alternative to preserve insects for DNA analysis, desiccants must be kept activated and the suitability of insects for dissecting can be poor [29].

Insects are also commonly preserved by suspending in solvents such as ethanol, but studies of this approach for samples to be assessed with NIRS indicate a slight reduction in accuracy relative to scanning fresh samples [30]. Also, solvents leave samples brittle and thus they are difficult to dissect. Other storage procedures used to store biological samples include ultra-cold storage in liquid nitrogen but the costs required for maintenance of liquid nitrogen is prohibitive in most field settings, particularly in resource limited tropical countries.

RNAlater® (Ambion, Inc., Austin, TX) is an aqueous, non-toxic storage reagent that has been used to preserve mosquito DNA [31] and other samples at room temperature up to one month [32], and indefinite storage time is possible if held at -20°C. Although RNAlater® is more costly than solvents or desiccants, samples are suitable for DNA extraction and dissection. However, NIRS has not been used to analyse mosquitoes stored in RNAlater®. Since RNAlater® is currently being used by some researchers to preserve mosquitoes and has some advantages over desiccants and solvents for subsequent DNA analysis and dissection, the objective of this study was to compare the accuracy of NIRS for determining the age and species of freshly anesthetized An. gambiae s.s. and An. arabiensis to those preserved in RNAlater®.

Methods

Mosquito rearing

Three An. arabiensis strains (Dongola, KGB, and Ifakara) and two An. gambiae s.s. strains (G3 and CDC) were used in this study. The Dongola and KGB An. arabiensis strains, were obtained from the Malaria Research and Reference Reagent Resource Center, Atlanta, Georgia, and reared at Kansas State University (KSU), Manhattan, KS, using methods described by Mayagaya et al[26]. The Ifakara An. arabiensis strain was reared in a semi-field system at the Ifakara Health Institute, Ifakara, Tanzania [33], as described by Sikulu et al[27]. The G3 and CDC An. gambiae s.s. strains are routinely reared at KSU and CDC Atlanta, respectively. Eight different ages (1, 5, 7, 9, 12, 14, 15 and 21 days) were investigated in this study.

Scanning and preserving

Mosquitoes were scanned by placing single mosquitoes below a fiber optic probe and collecting reflectance spectra using a LabSpec 5000 spectrometer (ASD Inc, Boulder, CO) as described by Mayagaya et al[26]. Live mosquitoes were anesthetized with chloroform before scanning, and then immediately put in 0.5 ml micro-centrifuge tubes before filling the tubes with RNAlater®. The tubes were then stored at -20°C. All mosquitoes remained frozen in RNAlater® for 1 to 3 weeks before rescanning. Although samples were placed at -20°C, Ambion specifications state that samples are stable for one week at room temperature, and for one month when refrigerated.

Data analysis

Spectra were analysed using Grams PLS/IQ (Thermo Galactic, Salem, NH). Cross-validation was used to determine the accuracy of predicting mosquito age or species from the fresh or preserved mosquitoes. The cross-validation results were then compared to determine if results from preserved mosquitoes were similar to those obtained from fresh insects. A cross-validation is a leave-one-out self-prediction method where mosquitoes from a set are used to predict the species or age of that same set. The number of factors used in developing models or analyzing results was determined from the Prediction Residual Error Sum of Squares (PRESS) and regression coefficients plots. Generally, all models used 5 to 7 factors. Additional details of the data analysis method have been described [26]. Although the spectrometer measures absorbance from 350-2500 nm, results from only the 500-2350 nm region are reported. The PLS/IQ Coefficients of Determination and the Regression Coefficient plots show that data becomes noisy outside this 500-2350 nm region. NIR spectra at shorter wavelengths are noisy due to low light energy at these wavelengths, and spectra at longer wavelengths are noisy due to low sensor sensitivity.

To test for statistical differences between accuracies obtained for age by NIRS for fresh and preserved specimens, the Mann-Whitney rank test was applied on residual age (difference between actual and predicted age) of fresh and RNAlater® preserved samples. Binary logistic regression was used to compare the accuracy of classification of samples preserved by the two methods, coding prediction accuracy as a binary dependent variable (correct classification or misclassification of each mosquito into <7 d or ≥7 d old age groups with misclassification as the dependent variable) and including true age category, preservation method, and with or without strain as independent predictors. The analysis was performed on the occurrence of misclassifications resulting from the within-species, cross-validation, analyses of strains maintained in Manhattan, KS, together with strains maintained in the Ifakara semi-field system. The 7 d old age category was used as the reference group for interpretation of the odds ratios (ORs) for the effect of actual age, and the KGB An. arabiensis mosquitoes were used as the reference category when interpreting the effect of strain. 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the results were calculated. Samples aged 21 d were omitted from the logistic regression analyses as this age group was not represented in all strain by age comparisons.

Results

Age-grading using the cross-validation technique

Table 1 shows accuracies of predicting mosquito age, or of predicting as young (<7 days) or old (≥7 days) for fresh and preserved samples for all strains reared at all locations. On average, all preserved mosquitoes were classed as young or old with approximately the same accuracy as fresh mosquitoes (P = 0.09).

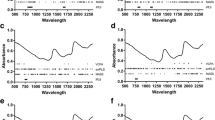

Figure 1 shows example spectra of fresh and preserved mosquitoes. The differences in absorbance values between fresh and preserved mosquitoes above about 1,500 nm are partly due to the presence of RNAlater®, particularly the absorbance peak at about 2150 nm.

When estimating age as a continuous outcome, inspection of the age prediction residuals for An. gambiae s.s. (Figure 2a) and three species of An. arabiensis (Figures 2b-2d) indicated that the prediction accuracy was generally to within ± 5 d of actual age and that there was tendency to overestimate the ages of 1-10 d old mosquitoes while the ages of mosquitoes > 10 d tended to be underestimated. However, there was no significant difference between age prediction residuals of fresh and RNAlater® preserved samples for all species tested (P > 0.05; Mann Whitney U test; Figure 2).

Age residuals for fresh and RNA later® preserved samples of three strains of An. arabiensis and one strain of An. gambiae s.s . as determined by Mann-Whitney rank test. No significant differences were observed between medians of residual age for fresh and RNAlater® preserved specimens for all four strains.

To investigate whether RNAlater® preservation, strain and actual age affected the success of the predictions of mosquitoes as young or old, multivariate binary logistic regression was performed on the occurrence of misclassification with preservation, strain, and actual age as independent predictor variables. The binary logistic regression model explained a highly significant proportion of the variance in misclassifications (χ2 = 193.76, df = 11, P < 0.001) and there was a significant effect of preservation (Wald = 7.30, P = 0.007) and a highly significant effect of actual age (Wald = 125.12, P = < 0.001); however, the effect of strain was non-significant (Wald = 6.98, P = 0.137). The analysis was, therefore, repeated without strain and again showed a significant effect of preservation (Wald = 5.95; P = 0.015) and a highly significant effect of actual age (135.61,P < 0.001). Mosquitoes preserved in RNAlater® had a 46% reduction in the likelihood of a misclassification than fresh mosquitoes (OR for misclassification = 0.64, 95% CI = 0.45 - 0.92) when holding actual age at a fixed value. When controlling for the effect of preservation, the probability of a misclassification for most age groups was not different from the 7 d reference age group, except for the 5 d age group, which had a 7 fold greater chance of being misclassified (OR = 6.73, 95% CI = 3.13 - 14.47) and the 15 d age category, which had an 83% reduction in the likelihood of being misclassified (OR = 0.17, 95% CI = 0.05 - 0.59).

Species identification

Anopheles arabiensis and An. gambiae s.s. were assigned a value of 1.0 and 2.0, respectively, for the purposes of developing the PLS models. Thus, mosquitoes close to the 1.5 threshold were most likely to be misclassified. When using a cross-validation with Dongola An. arabiensis and G3 An. gambiae s.s., there was no added advantage in using fresh or preserved mosquitoes to determine insect species, with classification accuracy about 80% for both species (Table 2).

Discussion

In this study, RNAlater® was used to preserve An. gambiae s.s. and An. arabiensis mosquitoes for subsequent scanning with NIRS to determine their age and species. Age-grading results were generally slightly better when using preserved samples than fresh ones. This may be due to the mosquitoes being more easily and consistently positioned after preserving in RNAlater® than when scanning fresh. The legs and wings of fresh mosquitoes often contact the NIR probe and thus scatter incident or reflected light, contributing to noise in the spectra and misclassifications. Also, some anesthetized mosquitoes move during scanning and further contribute to noise in the spectra. However, results for species identification were generally similar for both fresh and preserved samples.

In previous studies, NIRS estimated the age and species of fresh anesthetized laboratory-reared, semi-field reared and wild caught An. gambiae s.s. and An. arabiensis[26, 27]. This tool has also earlier been applied successfully to age grade stored-grain pests [34], biting midges [35] and house flies [30] as well as to differentiate between species and subspecies of termites [36]. This rapid and non-destructive technique can generally classify mosquitoes into young and old age groups, and differentiate between morphologically identical An gambiae s.s. and An arabiensis sibling species of An. gambiae s.l. The most recent study on An. gambiae s.l. indicated that NIRS could differentiate An. gambiae s.s. and An. arabiensis sibling species of the An. gambiae complex from semi-field and field settings with 89% and 90% accuracy, respectively, and as either young (<7 days) or old (≥7 days) from semi field system with 84% accuracy [27]. In this study, age and species prediction accuracies obtained were consistent with results obtained earlier on fresh samples [26, 27]. Since NIRS is a very fast technique, a large number of samples can be scanned in a very short period of time. Therefore, since a more representative sample of the population is analysed when compared to conventional techniques, the 80-90% level of accuracy reported herein and in previous studies may give researchers a better estimate of the true population structure when compared to other methods that may be limited to sample numbers 10 or 100 times smaller than can be used with this NIRS technique.

It was noted that when using the cross-validation technique, the accuracies for classifying very young (1 day) and old (9 and 15 days) was as high as 100% for both fresh and preserved samples. However, 6-8 days old mosquitoes were less accurately predicted as 7 days was nominated as the age defining young and the old ages in this and the previous age classification models [26, 27]. This age enables the distinction of female mosquitoes that are more likely to harbour mature parasites (sporozoites) in their salivary glands (≥7 days old) from those that are unlikely to be infectious (<7 days old). That is because 1-2 days are required for the maturation of the female mosquito before a blood meal is taken, and then malaria parasites acquired by females from an infected blood meal require a lengthy period of development inside the mosquito before they can be transmitted. This period is known as the Extrinsic Incubation Period (EIP). Depending on the environmental temperature, this period is estimated to be about 9-15 days for Anopheles mosquitoes that transmit malaria parasites [8]. Therefore, Anopheles must be at least 11 days old (2 days after enclosure and 9 days for EIP) to be able to transmit malaria.

When age was considered as a binary variable (young; < 7 d old and old; ≥7 d old), binary logistic regression enabled a multivariate analysis of the effects of RNAlater® preservation, strain and actual age on age prediction accuracy. A clear decrease in the likelihood of an age misclassification was observed when mosquitoes were preserved in RNAlater® over fresh mosquitoes. The greatest effect on age prediction accuracy was the actual age of the mosquitoes for both datasets. Interpretation of the within-age effects was not straightforward; however, there was a tendency for mosquitoes with an actual age furthest from the cut-off age of 7 d to have a lower likelihood of a misclassification. As may be expected, the likelihood of a misclassification of age did not differ between strains.

Age and species identification in any mosquito vector control intervention is a vital success determinant of that intervention and thus plays an important part in vector control programmes. This and our previous studies on NIRS provide evidence to support the application of NIRS as a rapid assessment tool for vector control interventions targeting An. gambiae s.s. and An. arabiensis to measure relative species abundance and survival characteristics. NIRS age and species classification has great potential for evaluation of the epidemiology and control of mosquito borne diseases and the ability to work with preserved specimens enables this technique to be applied under difficult field conditions.

The results presented herein show age and species can be predicted from fresh mosquitoes with accuracies similar to those achieved from insects preserved in RNAlater®. This dataset could be used to develop calibrations to predict age and species from lab-reared insects, but further work is needed to develop robust calibrations to include other sibling species, influences of physiological variations, wild mosquitoes, etc. These results were obtained from samples stored at -20°C, but no difference is expected if samples are stored at other temperatures or time intervals recommended by Ambion.

Conclusions

In summary, RNAlater® can be used to preserve samples for subsequent age-grading and species identification by NIRS with reasonable confidence when compared to scans from fresh mosquitoes. This is a significant step forward as samples can have extended preservation time for later processing from the most challenging field locations. Costs associated with RNAlater® are estimated at 3-13 cents for a pool of 5 mosquitoes. Although an ideal situation would allow longer preservation at room temperature, the ability to stabilize samples en route from remote field locations is a significant step forward for the use of NIR technology. Additional work should focus on developing robust calibrations to predict the age and species of several other strains from diverse ecological settings.

References

Bayoh MN, Mathias D, Odiere M, Mutuku F, Kamau L, Gimnig J, Vulule J, Hawley W, Hamel M, Walker E: Anopheles gambiae: historical population decline associated with regional distribution of insecticide-treated bed nets in western Nyanza Province, Kenya. Malar J. 2010, 9: 62-10.1186/1475-2875-9-62.

Russell T, Lwetoijera D, Maliti D, Chipwaza B, Kihonda J, Charlwood JD, Smith T, Lengeler C, Mwanyangala M, Nathan R, Knols BG, Takken W, Killeen GF: Impact of promoting longer-lasting insecticide treatment of bed nets upon malaria transmission in a rural Tanzanian setting with pre-existing high coverage of untreated nets. Malar J. 2010, 9: 187-10.1186/1475-2875-9-187.

Gillies M, Smith A: The effect of a residual house-spraying campaign in East Africa on species balance in the Anopheles funestus Group. The replacement of A. funestus Giles by A. rivulorum Leeson. Bull Entomol Res. 1960, 51: 243-252. 10.1017/S0007485300057953.

Garret-Jones C: Prognosis for interuption of malaria transmission through assessment of the mosquito's vectorial capacity. Nature. 1964, 204: 1173-1175. 10.1038/2041173a0.

Dye C: The analysis of parasite transmission by bloodsucking insects. Annu Rev Ent. 1992, 37: 1-19. 10.1146/annurev.en.37.010192.000245.

Magesa SM, Wilkes TJ, Mnzava AEP, Njunwa KJ, Myamba J, Kivuyo MDP, Hill N, Lines JD, Curtis CF: Trial of pyrethroid impregnated bednets in an area of Tanzania holoendemic for malaria Part 2. Effects on the malaria vector population. Acta Trop. 1991, 49: 97-108. 10.1016/0001-706X(91)90057-Q.

Robert V, Carnevale P: Influence of deltamethrin treatment of bed nets on malaroa transmission in the Kou valley, Burkina Faso. Bull World Health Organ. 1991, 69: 735-740.

Beier C: Malaria parasite development in mosquitoes. Annu Rev Ent. 1998, 43: 519-543. 10.1146/annurev.ento.43.1.519.

Saul A: Zooprophylaxis or zoopotentiation: the outcome of introducing animals on vector transmission is highly dependent on the mosquito mortality while searching. Malar J. 2003, 2: 32-10.1186/1475-2875-2-32.

Killeen GF, Smith TA: Exploring the contributions of bed nets, cattle, insecticides and excitorepellency to malaria control: a deterministic model of mosquito host-seeking behaviour and mortality. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007, 101: 867-880. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.04.022.

Killeen GF, Smith TA, Ferguson HM, Mshinda H, Abdulla S, Lengeler C, Kachur SP: Preventing childhood malaria in Africa by protecting adults from mosquitoes with insecticide-treated nets. PLoS Med. 2007, 4: e229-10.1371/journal.pmed.0040229.

Polovodova VP: The determination of the physiological age of female Anopheles by number of gonotrophic cycles completed. Med Parazitol Parazitar Bolezni. 1949, 18: 352-355.

Gillies M: A modified technique for the age-grading of populations of Anopheles gambiae. Ann Trop Med Parasit. 1958, 52: 261-273.

Gillies M: Studies on the dispersion and survival of Anopheles gambiae in East Africa, by means of marking and release experiments. Bull Entomol Res. 1961, 52: 99-127. 10.1017/S0007485300055309.

Detinova T: Age-grouping methods in Diptera of medical importance, with special reference to some vectors of malaria. Monogr Ser World Health Organ. 1962, 47: 13-191.

Gillies MT, Wilkes TJ: A study of the age composition of Anopheles gambiae Giles and A. funestus Giles in north-eastern Tanzania. Bull Entomol Res. 1965, 56: 237-262. 10.1017/S0007485300056339.

Caputo B, Dani R, Horne L, Petrarca V, Turillazzi S, Coluzzi M, Priestman A, Torre A: Identification and composition of cuticular hydrocarbons of the major Afrotropical malaria vector Anopheles gambiae s.s. (Diptera: Culicidae): analysis of sexual dimorphism and age-related changes. J Mass Spectrom. 2005, 40: 1595-1604. 10.1002/jms.961.

Marinotti O, Nguyen QK, Calvo E, James AA, Ribeiro JMC: Microarray analysis of genes showing variable expression following a blood meal in Anopheles gambiae. Insect Mol Biol. 2005, 14: 365-373. 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2005.00567.x.

Marinotti O, Calvo E, Nguyen QK, Dissanayake S, Ribeiro JMC, James AA: Genome-wide analysis of gene expression in adult Anopheles gambiae. Insect Mol Biol. 2006, 15: 1-12. 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2006.00610.x.

Cook PE, Sinkins SP: Transcriptional profiling of Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes for adult age estimation. Insect Mol Biol. 2010, 19: 745-751. 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2010.01034.x.

Wang M-H, Marinotti O, James AA, Walker E, Githure J, Yan G: Genome-wide patterns of gene expression during aging in the African malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. PLoS ONE. 2010, 5: e13359-10.1371/journal.pone.0013359.

Cook P, Hugo L, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Williams C, Chenoweth S, Ritchie S, Ryan P, Kay B, Blows M, O'Neill S: Predicting the age of mosquitoes using transcriptional profiles. Nat Protoc. 2007, 2: 2796-2806. 10.1038/nprot.2007.396.

Scott J, Brogdon W, Collins F: Identification of single specimens of the Anopheles gambiae c omplex by the polymerase chain reaction. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993, 49: 520-529.

Bass C, Williamson M, Wilding C, Donnelly M, Field L: Identification of the main malaria vectors in the Anopheles gambiae species complex using a TaqMan real-time PCR assay. Malar J. 2007, 6: 155-10.1186/1475-2875-6-155.

Vezenegho S, Bass C, Puinean M, Williamson M, Field L, Coetzee M, Koekemoer L: Development of multiplex real-time PCR assays for identification of members of the Anopheles funestus species group. Malar J. 2009, 8: 282-10.1186/1475-2875-8-282.

Mayagaya VS, Michel K, Benedict MQ, Killeen GF, Wirtz RA, Ferguson HM, Dowell FE: Non-destructive determination of age and species of Anopheles gambiae s.l. using near-infrared spectroscopy. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009, 81: 622-630. 10.4269/ajtmh.2009.09-0192.

Sikulu M, Killeen G, Hugo L, Ryan P, Dowell K, Wirtz R, Moore S, Dowell F: Near-infrared spectroscopy as a complementary age grading and species identification tool for African malaria vectors. Parasites & Vectors. 2010, 3: e49-10.1186/1756-3305-3-49.

Gray E, Bradley T: Physiology of dessication resistance in Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles arabiensis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005, 73: 553-559.

Quicke DLJ, Belshaw R, Lopez-Vaamonde C: Preservation of hymenopteran specimens for subsequent molecular and morphological study. Zoologica Scripta. 1999, 28: 261-267. 10.1046/j.1463-6409.1999.00004.x.

Perez-Mendoza J, Dowell FE, Broce AB, Throne JE, Wirtz RA, Xie F, Fabrick JA, Baker JE: Chronological age-grading of house flies by using near-infrared spectroscopy. J Med Ent. 2002, 39: 499-508. 10.1603/0022-2585-39.3.499.

Hugo LE, Cook PE, Johnson PH, Rapley LP, Kay BH, Ryan PA, Ritchie SA, O'Neill SL: Field validation of a transcriptional assay for the prediction of age of uncaged Aedes aegypti mosquitoes in norther Australia. PLoS Neglected Trop Dis. 2010, 4: e608-10.1371/journal.pntd.0000608.

Gorokhova E: Effects of preservation an dstorage of microcrustaceans in RNAlater on RNA and DNA degradation. Limnol Oceanogr: Methods. 2005, 3: 143-148.

Ferguson H, Ng'habi K, Walder T, Kadungula D, Moore S, Lyimo I, Russell T, Urassa H, Mshinda H, Killeen G, Knols B: Establishment of a large semi-field system for experimental study of African malaria vector ecology and control in Tanzania. Malar J. 2008, 7: e158-10.1186/1475-2875-7-158.

Perez-Mendoza J, Throne JE, Dowell FE, Baker JE: Chronological age-grading of three species of stored- product beetles by using near-infrared spectroscopy. J Econ Ent. 2002, 97: 1159-1167.

Reeves WK, Peiris KHS, Scholte EJ, Wirtz RA, Dowell FE: Age-grading the biting midge Culicoides sonorensis using near-infrared spectroscopy. Med Vet Ent. 2010, 24: 32-37. 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2009.00843.x.

Aldrich BT, Maghirang EB, Dowell FE, Kambhampati S: Identification of termite species and subspecies of the genus Zootermopsis using near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy. J Insect Sci. 2007, 7: 1-7.

Acknowledgements

We thank Paul Howell (Malaria Research and Reference Reagent Resource Center, CDC) for providing mosquitoes; Tinea Graves and KaraJo Sprigg for rearing mosquitoes at KSU; Ally Daraja for rearing mosquitoes at IHI; and Peter O'Rourke (QIMR) for advice with statistical analysis. Thanks also to Hassan Mtambala, Peter Pazia, Daniel Lugiko, Nuru Nchimbi and Japheth Kihonda of IHI for their technical assistance. This study was supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (awards 51431 and 45114), a National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia, programme grant (496601), NIH grant P20RR017686 subaward to KM, as well as a Research Career Development Fellowship (076806) provided to GFK by the Wellcome Trust, and IAEA fellowship funding provided to FED.

Mention of trade names or commercial products in this publication is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

FED and KMD conceived the study; RAW, KM, SM, GFK, and FED designed the experiments; MS and KMD collected data; MS, KHSP, LH, GFK, and FED analysed the data; MS and FED drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Sikulu, M., Dowell, K.M., Hugo, L.E. et al. Evaluating RNAlater® as a preservative for using near-infrared spectroscopy to predict Anopheles gambiae age and species. Malar J 10, 186 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-10-186

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-10-186