Abstract

The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) accessory protein Vpr induces apoptosis after cell cycle arrest at the G2 phase in primate cells. We have reported previously that C81, a carboxy-terminally truncated form of Vpr, interferes with cell proliferation and results in apoptosis without G2 arrest. Here, we investigated whether this property of Vpr and C81 could be exploited for use as a potential anticancer agent. First, we demonstrated that C81 induced G1 arrest and apoptosis in all tumor cells tested. In contrast, Vpr resulted in G2 arrest and apoptosis in HeLa and 293 T cells. Vpr also suppressed the damaged-DNA-specific binding protein 1 (DDB1) in HepG2 cells, thereby inducing apoptosis without G2 arrest. G2 arrest was restored when DDB1 was overexpressed in cells that also expressed Vpr. Surprisingly, C81 induced G2 arrest when DDB1 was overexpressed in HepG2 cells, but not in HeLa or 293 T cells. Thus, the induction of Vpr- and C81-mediated cell cycle arrest appears to depend on the cell type, whereas apoptosis was observed in all tumor cells tested. Overall, Vpr and C81 have potential as novel therapeutic agents for treatment of cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) accessory gene vpr encodes a 15-kDa protein of 96 amino acids. Vpr has multiple biological functions, including nuclear import of the preintegration complex [1–4], transactivation of the viral promoter [5], regulation of splicing [6–8], induction of apoptosis, and cell cycle arrest at the G2 phase [9, 10]. The induction of cell cycle arrest at G2 is particularly important because the transcriptional activity of the HIV-1 long terminal repeat is most active in G2 [11, 12], which leads to efficient virus production. Moreover, the cytostatic activity of Vpr is well conserved among the primate lentiviruses [13, 14]. Thus, Vpr-mediated cell cycle arrest may play an important role in the life cycle of HIV-1.

Vpr induces G2 arrest by activating the ataxia telangiectasia-mutated and Rad3-related protein (ATR) [15, 16]. ATR is a sensor of replication stress that is activated by the stalling of replication forks after various cellular insults, such as deoxyribonucleotide depletion, topoisomerase inhibition, or UV light induced DNA damage [17]. A recent report suggests that Vpr induces ATR activation, leading to the induction of G2 arrest [18]. Additionally, the Vpr-binding protein (VprBP), which was isolated as a Vpr coprecipitating protein, acts as a substrate specificity determinant in a Cul4- and damaged-DNA-specific binding protein 1 (DDB1)-based E3 ubiquitin ligase complex [19–22]. Thus, VprBP was renamed the DDB1- and Cul4A-associated factor 1 (DCAF1). Several groups have recently confirmed that Vpr physically associates with DCAF1 and that Vpr is capable of binding to a larger complex consisting of Cul4A, DDB1, and DCAF1 [18, 23–27]. The interaction between Vpr and DDB1 could cause the accumulation of damaged DNA by preventing DNA repair. The failure of DDB1 to bind DNA and mediate the repair of DNA lesions generated during S phase may be sensed by the cell as DNA damage, which would activate ATR, resulting in G2 arrest followed by apoptosis [26]. However, Vpr mutants such as Vpr(1-78) or Vpr(R80A) are able to bind to DCAF1, but are unable to induce G2 arrest [24, 28]. The association of Vpr with the E3 ligase complex is necessary but not sufficient to induce G2 arrest, suggesting that Vpr may induce the ubiquitination and degradation of an unknown cellular factor.

Several researchers have demonstrated that Vpr is capable of inducing cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in cancer cell lines, including those defective for some tumor suppressor genes and DNA repair genes [29, 30]. In addition, Siddiqui and colleagues [31] have reported that Vpr is involved in DNA damage that leads to the disruption of the cell cycle. These results suggest that Vpr mimics the action of the anticancer agent cisplatin. Furthermore, it has also been reported that Vpr has anti-melanoma activity in vivo [32, 33]. These studies suggest that Vpr has the potential for therapeutic application as a tumor suppressor. Interestingly, we have found that a carboxy-terminally truncated form of the Vpr, C81, induces G1 arrest, but not G2 arrest or apoptosis, via disruption of mitochondrial function [34, 35]. We have also shown that caspase-3 activity induced by C81 is higher than that induced by Vpr in human cells [35]. Thus, our results suggest that C81 may be a strong inducer of tumor cell apoptosis and may have potential as an anti-tumor agent.

In this study, we examined whether C81, as well as Vpr, induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in several tumor cell lines, and examined the expression patterns of factors associated with apoptosis and cell cycle arrest.

Results

The expression of Vpr and C81 induces apoptosis in tumor cells

Vpr has previously been demonstrated to induce G2 cell cycle arrest as well as apoptosis in a number of tumor cells [29, 30]. Previously, we found that C81, a carboxy-terminally truncated form of Vpr, is a strong inducer of apoptosis with G1 arrest, but not G2 arrest, of the cell cycle, and that the apoptotic activity of C81 is stronger than that of Vpr in human cells [35]. Based on the growth arresting and apoptosis inducing properties in tumor cells, C81 and Vpr have potential therapeutic applications for treating cancer. To further investigate this potential, we examined whether Vpr and C81 can induce apoptosis in tumor cells. We transiently transfected two human tumor cell lines, HeLa and HepG2, as well as 293 T cells, with a pME18Neo expression vector encoding Flag-tagged wild-type Vpr, C81, or the empty vector pME18Neo-Flag as a control. We examined the expression of Vpr and C81, 48 h post-transfection by Western blot analysis using the anti-Flag M2 monoclonal antibody. Fig. 1 shows protein bands with molecular masses that are consistent with the calculated masses of the sequences of Flag-tagged Vpr and Flag-tagged C81.

Construction and expression of Vpr and C81. (A) Plasmids containing cDNA for Vpr and C81 were generated from HIV-1NL4-3. Schematic presentation of the predicted first α-helical domain (αH1), second α-helical domain (αH2), third α-helical domain (αH3) and the arginine rich region of Vpr are indicated. (B) Western blotting of wild-type Vpr and C81. HeLa, HepG2, and 293 T cells were transfected with pME18Neo encoding Flag-tagged wild-type Vpr or C81, or the empty vector control pME18Neo-Flag, together with pSV-β-galactosidase. Transfected cells were collected and lysed 48 h after transfection. Lysates with equal β-galactosidase activity were subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-Flag.

Next, we detected apoptotic cells by monitoring fluorescence after staining the cells with Hoechst 33258. HeLa, HepG2, and 293 T cells were transfected with the pME18Neo empty vector, or the expression plasmids for Vpr or C81. At 48 h post-transfection, cells were fixed and stained with anti-Flag followed by Alexa-488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. To monitor nuclear morphology, cells were stained with Hoechst 33258. The cells that expressed either Vpr or C81 had condensed chromatin, a hallmark of cells undergoing apoptosis (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, we assessed apoptosis in Vpr- and C81-expressing cells by measuring the activity of caspase-3, which plays an essential role in the induction of apoptosis (Fig. 2B). Caspase-3 activity was significantly higher in the Vpr- and C81-expressing cells compared to the control vector transfected cells. Caspase-3 activity was approximately two-five fold higher than in the cells transfected with the control pME18Neo empty vector. Interestingly, caspase-3 activity was significantly higher in cells that had been transfected with the C81 expression vector, compared to cells transfected with the Vpr expression vector. Conversely, treatment with the caspase-3 specific inhibitor, Z-DEVD-FMK, suppressed the activity of caspase-3 in all transfected cells, including cells transfected with the control pME18Neo empty vector. These results strongly suggested that Vpr and C81 can induce apoptosis in the HepG2 and HeLa cell lines.

Vpr and C81 induce apoptosis in tumor cells. (A) HeLa, HepG2, and 293 T cells were transfected with pME18Neo encoding Flag-tagged wild-type Vpr or C81, or the control pME18Neo-Flag. At 48 h post-transfection, cells were fixed and stained with anti-Flag, followed by Alexa-488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. Finally, cells were stained with Hoechst 33258 to monitor the nuclear morphology. Apoptotic bodies (arrowheads) were identified using confocal laser scanning microscopy. (B) HeLa, HepG2, and 293 T cells were transfected with the pME18Neo plasmid encoding Flag-tagged wild-type Vpr or C81, or the control pME18Neo-Flag, together with pSV-β-galactosidase. Cells were treated with (filled columns) or without (open columns) inhibitors of caspase-3. At 30 h (293 T), 36 h (HeLa), or 48 h (HepG2) post-transfection, caspase-3 activity was measured and normalized to the β-galactosidase activity. Each column and error bar represents the mean ± SD of measurements from three samples. (C) HeLa, HepG2, and 293 T cells were transfected with pME18Neo encoding Flag-tagged wild-type Vpr or C81, or the control pME18Neo-Flag with or without the GFP expression vector pEGFP-N1. GFP was used as a reporter to discriminate between transfected and untransfected cells. At 47 h (293 T), 38 h (HeLa), or 58 h (HepG2) post-transfection, cells were stained with PE-Annexin V and 7-AAD to identify apoptotic cells, or anti-mouse IgG2b-PE (Nippon BD Company Ltd) and 7-AAD as a negative control. The percentages of Annexin V-positive and 7-AAD negative cells relative to GFP-positive cells indicate the level of Vpr or C81 associated apoptosis.

The apoptotic activity of Vpr and C81 was further quantified with flow cytometry by combined staining of transfected samples with phycoerythrin-(PE)-Annexin V and 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD) (Fig. 2C). A prominent event in early apoptosis is the exposure of phosphatidylserine (PS) on the outer leaflet of the cell membrane. Cell surface exposed PS can be specifically detected with PE-Annexin V. At late stages of apoptosis, or in necrosis, cell membrane integrity is lost, allowing entry of the DNA-binding dye 7-AAD into cells. The population of Annexin V positive and 7-AAD negative apoptotic cells among cells expressing Vpr or C81 reached to approximately 5.52% and 7.15% in HeLa cells, respectively, and 10.32% and 12.45% in HepG2 cells, respectively. These values were much higher than in cells that had been transfected with the control pME18Neo empty vector or mock transfected (3.71% and 1.35% in HeLa cells, respectively, and 9.55% and 0% in HepG2 cells, respectively). Interestingly, the populations of apoptotic cells in both tumor cell lines were significantly higher in cells transfected with the C81 expression vector, compared to cells transfected with the Vpr expression vector. Similar results were obtained with 293 T cells. Only a small population of 293 T cells transfected with either Vpr, C81, or the control vector bound Annexin V (2.02%, 2.28%, and 1.65%, respectively). Since these results show the same trends as the Hoechst 33258 staining (Fig. 2A) and the caspase-3 activity (Fig. 2B), we conclude that Vpr and C81 induce apoptosis in the human tumor cell lines HepG2 and HeLa.

Vpr and C81 induce apoptosis and caspase-9 activity

Vpr and C81 are reported to target mitochondria to induce apoptosis [10, 34]. To examine whether Vpr and C81 target mitochondria in tumor cells, we measured caspase-8 and caspase-9 activity. Caspase-8 is activated by FasL and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), whereas caspase-9 is activated by the disruption of mitochondrial function. In tumor cells, as well as 293 T cells, caspase-9 activity induced by Vpr or C81 was higher than caspase-8 activity (Fig. 3). Caspase-9 activity in Vpr or C81-transfected cells was significantly higher than in the control vector transfected cells (p < 0.01). In addition, although apoptosis induced by Vpr or C81 was significantly inhibited when inhibitors of caspase-9 were added to the Vpr- or C81-transfected cells (p < 0.01), a caspase-8 inhibitor only slightly inhibited apoptosis in these transfected cells. These results suggest that both Vpr and C81 induce apoptosis via the activation of caspase-9.

Vpr and C81 induce apoptosis increased caspase-9 activity. HeLa, HepG2, and 293 T cells were transfected with pME18Neo encoding Flag-tagged wild-type Vpr or C81, or the control pME18Neo-Flag, together with pSV-β-galactosidase before treatment with (filled columns) or without (open columns) a caspase-8 or caspase-9 inhibitor. At 30 h (293 T), 36 h (HeLa), or 48 h (HepG2), post-transfection, caspase-8 or caspase-9 activity was measured and normalized to the β-galactosidase activity. Columns and error bars represent the mean ± SD of measurements from three samples.

Induction of cell cycle arrest by Vpr and C81 depends on the cell type

Vpr induces G2 cell cycle arrest in various human cells [10], whereas C81 induces G1 cell cycle arrest in human and rodent cells [34, 35]. To determine whether Vpr and C81 induce cell cycle arrest in HeLa, HepG2, or 293 T cells, we transfected these cells with pME18Neo encoding Flag-tagged wild-type Vpr or C81, or the control plasmid pME18Neo-Flag, together with a small amount of a green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression vector, pEGFP-N1, to identify transfected cells. Cells were fixed and stained with propidium iodide (PI) 48 h post-transfection and analyzed by flow cytometry. We measured the DNA content of GFP-positive cells to determine the distribution of cells across the cell cycle (Fig. 4A). C81 failed to arrest the cell cycle at the G2 phase in HeLa, 293 T, or HepG2 cells. To confirm this result, we prepared total cell extracts and examined cyclin B1, which controls the cell cycle in the G2 phase, by Western blot analysis (Fig. 4B). C81 failed to induce accumulation of cyclin B1 in HeLa, 293 T, or HepG2 cells, suggesting that C81 failed to arrest the cell cycle at the G2 phase in these cells. In contrast, transfection with Vpr led to an increase in the number of HeLa and 293 T cells in the G2 phase of the cell cycle, compared with cells that had been transfected with the control pME18Neo-Flag. Moreover, Vpr induced accumulation of cyclin B1 in HeLa and 293 T cells. However, Vpr was unable to arrest the cell cycle at the G2 phase, or to induce accumulation of cyclin B1, in HepG2 cells (Fig. 4).

Induction of cell cycle arrest by Vpr or C81 is dependent on the cell type. (A) HeLa, HepG2, and 293 T cells were transfected with pME18Neo encoding Flag-tagged wild-type Vpr or C81, or the control pME18Neo-Flag, together with the GFP expression plasmid pEGFP-N1. At 48 h post-transfection, cells were fixed and stained with PI. GFP-positive cells were analyzed by flow cytometry using CELL Quest for acquisition and ModFit LT for quantitative analysis of DNA content. Arrows indicate the peaks of cells at the G1 and G2/M phases. The G2/M:G1 ratios are indicated at the upper right in each graph. (B) HeLa, HepG2, and 293 T cells were transfected with pME18Neo encoding Flag-tagged wild-type Vpr or C81, or the control plasmid pME18Neo-Flag, together with pSV-β-galactosidase. At 48 h post-transfection, the cells were collected and lysed. Lysates with equal β-galactosidase activity were subjected to Western blot analysis using a cyclin B1 specific antibody.

DDB1 overexpression enables G2 cell cycle arrest by Vpr and C81

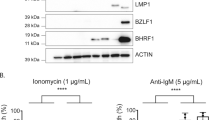

It has recently been reported that Vpr targets the DCAF1 adaptor of the Cul4A-DDB1 ligase to induce cell cycle arrest at the G2 phase [28]. Thus, we examined the expression levels of DDB1 in various cell lines, including HepG2 cells, which do not arrest at G2 when transfected with Vpr (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, Western blot analysis revealed that Vpr, but not C81, could inhibit DDB1 expression in HepG2 cells. In contrast to Vpr, C81 had no effect on the expression of DDB1 in HepG2 cells.

Overexpression of DDB1 induces G 2 cell cycle arrest by Vpr and C81. (A) HeLa, HepG2, and 293 T cells were transfected with pME18Neo encoding Flag-tagged wild-type Vpr or C81, or the control pME18Neo-Flag, together with pSV-β-galactosidase. At 48 h post-transfection, the cells were collected and lysed. Lysates with equal β-galactosidase activity were subjected to Western blotting with either a DDB1 specific antibody or the Flag-specific MAb M2. (B) HeLa, HepG2, and 293 T cells were transfected with pME18Neo encoding Flag-tagged wild-type Vpr or C81, or the control pME18Neo-Flag, together with the pDDB1-IRES-GFP expression plasmid and pSV-β-galactosidase. Lower panel: 48 h post-transfection, cells were fixed and stained with PI. GFP-positive cells were analyzed by flow cytometry using CELL Quest for acquisition and ModFit LT for quantitative analysis of DNA content. Arrows indicate the peaks of cells at the G1 and G2/M phases. The G2/M:G1 ratio is indicated at the upper right in each graph.

To determine the effect of DDB1 in HepG2 cells, we constructed a DDB1 expression vector, pDDB1-IRES-GFP, which was co-transfected with either the Vpr or C81 expression vector. As shown in Fig. 5B, overexpression of DDB1 resulted in cell cycle arrest at G2 in HepG2 cells transfected with Vpr. Overexpression of DDB1 had no effect on the induction of G2 arrest by Vpr in HeLa or 293 T cells. This result clearly suggests that DDB1 plays an essential role in Vpr-induced cell cycle arrest. Strikingly, C81, which was completely inactive for G2 arrest in all cell lines tested, was able to induce G2 arrest in HepG2 cells overexpressing DDB1, but not in HeLa or 293 T cells overexpressing DDB1. These results suggest that C81 can cause G2 arrest independent of its ability to induce apoptosis via G1 arrest of the cell cycle, although the former activity is cell type dependent.

Discussion

The results of the present study show that C81 and Vpr induce apoptosis via the activation of caspase-9 in tumor cells such as HeLa, HepG2, and 293 T cells. A previous report indicated that Vpr and C81 induced apoptosis in rodent cell lines [34], suggesting that the induction of apoptosis by Vpr and C81 may be ubiquitous. Vpr displayed cell type specificity in terms of induction of G2 arrest but not apoptosis. Vpr resulted in apoptosis that was coupled with G2 arrest in HeLa and 293 T cells, whereas Vpr induced apoptosis without G2 arrest in HepG2 cells. Similarly, we previously reported that, in rodent cell lines, Vpr fails to induce cell cycle arrest at G2 [34]. The present study also shows that DDB1 is required for Vpr-mediated G2 arrest. Notably, the expression of Vpr, but not C81, suppressed DDB1 expression in HepG2 cells where it induced apoptosis without G2 arrest. In contrast, Vpr induced G2 arrest and apoptosis in HeLa and 293 T cells.

Interestingly, G2 arrest was restored when DDB1 was overexpressed by transfection during Vpr expression. Additionally, C81, which was unable to induce G2 arrest in all cells tested, induced G2 arrest when overexpressed with DDB1 in HepG2 cells, but not in HeLa or 293 T cells. These results indicate that the induction of cell cycle arrest at the G2 phase by Vpr or C81 may depend on the level of DDB1 expression in Vpr- and C81-transfected cells. Finally, we demonstrated that the apoptotic properties of C81, as well as those of Vpr, are strong inducers of intra-tumoral apoptosis. These proteins hold great promise as the basis for an anti-cancer treatment, particularly since C81 caused apoptosis in the tumor cell line HepG2, in which Vpr failed to induce G2 arrest.

Vpr binding to the adenine nucleotide transporter (ANT) protein of the inner mitochondrial membrane was previously shown to induce apoptosis through permeabilization of the mitochondrial outer membrane [9]. Vpr has also been reported to activate caspase-9 and apoptosis in other human tumor cell lines [29]. Moreover, C81 induced cell cycle arrest at the G1 phase and apoptosis through activation of caspase-3 and caspase-9 in rodent cells, which was associated with the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria into the cytosol and disruption of the mitochondrial transmembrane potential [34]. We have demonstrated here that caspase-9 is activated during Vpr and C81 induced apoptosis, confirming that the induction of apoptosis by Vpr and C81 is caused by mitochondrial dysfunction.

Analysis of the three-dimensional structure of Vpr by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) revealed three well-defined α-helixes, amino acids 17-33 (αH3), 38-50 (αH2), and 56-77 (αH3), which are surrounded by flexible amino- and carboxy-terminal domains [36]. Siddiqui and colleagues have suggested that the αH2 domain in Vpr is responsible for DNA damage [31]. Interestingly, Vpr Delta (37-50) failed to induce cell cycle arrest or apoptosis, or to induce Ku70 or Ku80 expression or suppress tumor growth. However, the peptide activated the HIV-1 LTR, resulting in its localization to the nucleus where it promoted nonhomologous end-joining [31]. C81 shares the αH2 domain with Vpr; thus, C81 may have the ability to induce DNA damage. In this study, both wild-type Vpr and C81 induced apoptosis that may be triggered by DNA damage involving DDB1.

Vpr stabilization was recently reported to be dependent on DDB1, suggesting that the Cul4A-DDB1-DCAF1 ubiquitin ligase is required to protect Vpr from proteasomal degradation [37]. Here, we demonstrated that, in HepG2 cells, Vpr was expressed stably despite a decrease in DDB1 expression. Therefore, further studies will be required to clearly define whether DDB1 protects Vpr from proteasomal degradation in HepG2 cells. Whether this downregulation of DDB1 occurs at the transcriptional or protein level, and whether the interaction of Vpr with the E3 ligase complex is involved in the biological activity should also be addressed in future studies.

The activation of G2 arrest by Vpr is induced via binding and, possibly, activation of the Cul4A-DDB1-DCAF1 ligase [28]. In addition, DCAF1 engages in simultaneous interactions with DDB1 and Vpr, leading to the formation of a ternary complex. The domain of Vpr that binds to DCAF1 was mapped to the leucine-rich 60LIRILQQLL68 motif in the αH3 domain of Vpr [38]. The truncation of the C-terminal region of Vpr up to residue H78 or the replacement of arginine at position 80 by alanine did not affect the Vpr interaction with DCAF1 but affected the ability of Vpr to induce G2 arrest [18, 24]. Similarly, our previous results [3, 35, 39, 40] showed that C81, a carboxy-terminal truncated form of Vpr, was completely inactive for G2 arrest in all cells tested. Together, these experiments indicate that interactions between Vpr and DCAF1 are necessary but not sufficient for the induction of G2 arrest and that the carboxy-terminal domain of Vpr is likely to be required for the recruitment of a cellular protein whose ubiquitination and degradation leads to G2 arrest. Interestingly, we found that C81 resulted in G2 arrest when overexpressed with DDB1 in HepG2 cells, but not in HeLa or 293 T cells. This finding suggests that C81 may interact with DCAF1, causing G2 arrest via activation of the CUl4A-DDB1-DCAF1 ligase, when DDB1 is overexpressed in HepG2 cells. Additionally, the ability of C81 to induce apoptosis with G1 arrest may be a dominant function compared to induction of G2 arrest in almost all other cells. Moreover, the expression of Vpr suppressed DDB1 activity in HepG2 cells but not in HeLa cells or 293 T cells, resulting in the induction of apoptosis without G2 arrest. The overexpression of DDB1 succeeded in inducing Vpr-mediated G2 arrest in HepG2 cells, suggesting that DDB1 is a key component of Vpr-mediated G2 arrest. Thus, the induction of G2 arrest by Vpr and C81 may be dependent on the expression level of DDB1.

Conclusion

Vpr has been reported to induce apoptosis in transformed cells and human tumor cell lines [29, 30]. Furthermore, Vpr successfully induces the regression of murine melanoma tumors in vivo [33]. Because our data indicate that Vpr and C81 induce apoptosis in tumor cell lines, these factors could be potentially useful in the development of novel therapeutic treatments for cancer.

Materials and methods

Plasmid construction

The expression vector pME18Neo encoding a Flag-tagged wild-type Vpr or C81, and the control vector pME18Neo have been described previously [40, 41]. A red-shifted variant of wild-type GFP that has been modified for brighter fluorescence was encoded by pEGFP-N1 and used as a reporter to identify transfected cells [42]. Bacterial β-galactosidase encoded by pSV-β-galactosidase was included for normalization of the transfection efficiency [40]. The mRNA of human DDB1 was amplified by RT-PCR from RNA derived from Jurkat cells. RT was performed with an oligo-dT primer and PCR was performed using the following primers: 5'-gcggccgcacatgtcgtacaactacg-3' and 5'-gtcgacgctaatggatccgagttagc. The resulting amplicon served as the template for a second PCR reaction using the primers 5'-ataagaatgcggccgcacatgtcgt-3' and 5'-tggccgacgtcgacgctaatggatc-3'. The second PCR product was subcloned between the Not I-Sal I sites of pIRES-hrGFP-2a (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), generating pDDB1-IRES-GFP.

Cell lines and transfection

HeLa cells, which are human epithelial cervical carcinoma cells [43, 44], and 293 T cells that stably express the large T-antigen of simian sarcoma virus 40 [45] were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS), penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). HepG2 cells, which were derived from a well differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma [46, 47] were obtained from the RIKEN Bio Resource Center (Ibaraki, Japan) and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FCS, penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids. Transfection of cells was performed using FuGENE HD (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Western blotting

At 24 or 48 h post-transfection with the indicated plasmids and pSV-β-galactosidase, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and divided into two aliquots. One aliquot was subjected to an assay for β-galactosidase activity with the FluoReporter LacZ/Galactosidase Quantitation kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), to monitor the transfection efficiency. The other aliquot of cells was lysed for 10 min on ice in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 0.1% desoxycholate supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail1 (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo). Lysates were centrifuged for 10 min at 20,000 g, mixed with sample buffer for SDS-PAGE and then boiled for 5 min. Protein concentrations were determined with a BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL), with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the standard. Aliquots with equal β-galactosidase activity were examined by Western blotting as described previously [35, 39]. An anti-Flag MAb (M2) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), anti-Cyclin-B1 (H-20) antibody (Santa Cruz biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-DDB1 MAb (ZYMED Laboratories Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), horseradish-peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated sheep anti-mouse IgG (Amersham Bioscience, Uppsala, Sweden) and HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgGs (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) were used for Western blotting. Signals were visualized after treatment of the membrane with SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Analysis of apoptosis

The activities of caspase-3, 8, and 9 were determined using caspase-3/CPP32, caspase-8/Flice or caspase-9/Mch6 fluorometric assay kits (Bio Vision, Mountain View, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocols. Briefly, 30 h or 40 h post-transfection, in the presence or absence of 2 μM caspase-3, 8, or 9 specific inhibitors (Bio Vision, Mountain View, CA), cells were harvested and lysed with cell lysis buffer. Each cell lysate was incubated with the substrate for 2 h at 37°C. Measurements were made using a multilabel cell counter (Model1420; Wallac Arvo; Parkin Elmer, Wellesley, MA).

Hoechst 33258 was used to visualize the condensation and clumping of chromatin. At 48 h post-transfection with pME18Neo encoding Flag-tagged wild-type Vpr, C81, or the control pME18Neo-Flag, HeLa cells that were grown on coverslips were fixed with 4% formaldehyde followed by 70% ethanol. Flag-tagged-Vpr or C81 was detected by indirect immunofluorescent staining with the Flag-specific MAb M2 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), followed by Alexa-488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. The cells were then stained with Hoechst 33258 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Apoptotic bodies were characterized using confocal laser scanning microscopy (FV 1000; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

To detect Annexin V positive apoptotic cells, we used flow cytometry. At the indicated times post-transfection, cell monolayers were washed with PBS, detached with trypsin and EDTA, and 1 × 105 cells were stained with 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD) and Annexin V-PE (Nippon BD company Ltd, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Incubation of cell monolayers for 8 to 13 hours with actinomycin D (2 μg/ml) provided positive controls for apoptosis. For each sample, 10,000 GFP positive cells were analyzed using a FACS Calibur instrument (BD Biosciences, Japan) and the FCS Express version 3 software (De Novo software, CA).

Analysis of the cell cycle

At 48 h post-transfection, cells were harvested and fixed with 1% formaldehyde and then 70% ethanol. Fixed cells were incubated in PBS that contained RNase A (50 μg/ml) at 37°C for 30 min and then stained with PI (50 μg/ml). The fluorescence of 20,000 cells was analyzed using a FACS Calibur instrument (Becton-Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) with the CELL Quest software (Becton-Dickinson, Mountain View, CA). Data were extracted after gating to eliminate cells in which GFP emitted strong fluorescence. Ratios of the numbers of cells in the G1 and G2/M phase (G2/M:G1 ratios) were calculated using the ModFit LT Software (Verity Software House, Topsham, ME).

Statistical methodology

Statistical analyses were conducted using R version 2.8(1) [48].

References

Aida Y, Matsuda G: Role of Vpr in HIV-1 nuclear import: therapeutic implications. Curr HIV Res. 2009, 7 (2): 136-143. 10.2174/157016209787581418.

Heinzinger NK, Bukinsky MI, Haggerty SA, Ragland AM, Kewalramani V, Lee MA, Gendelman HE, Ratner L, Stevenson M, Emerman M: The Vpr protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 influences nuclear localization of viral nucleic acids in nondividing host cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994, 91 (15): 7311-7315. 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7311.

Kamata M, Nitahara-Kasahara Y, Miyamoto Y, Yoneda Y, Aida Y: Importin-alpha promotes passage through the nuclear pore complex of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr. J Virol. 2005, 79 (6): 3557-3564. 10.1128/JVI.79.6.3557-3564.2005.

Nitahara-Kasahara Y, Kamata M, Yamamoto T, Zhang X, Miyamoto Y, Muneta K, Iijima S, Yoneda Y, Tsunetsugu-Yokota Y, Aida Y: Novel nuclear import of Vpr promoted by importin alpha is crucial for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in macrophages. J Virol. 2007, 81 (10): 5284-5293. 10.1128/JVI.01928-06.

Kino T, Gragerov A, Slobodskaya O, Tsopanomichalou M, Chrousos GP, Pavlakis GN: Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) accessory protein Vpr induces transcription of the HIV-1 and glucocorticoid-responsive promoters by binding directly to p300/CBP coactivators. J Virol. 2002, 76 (19): 9724-9734. 10.1128/JVI.76.19.9724-9734.2002.

Hashizume C, Kuramitsu M, Zhang X, Kurosawa T, Kamata M, Aida Y: Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr interacts with spliceosomal protein SAP145 to mediate cellular pre-mRNA splicing inhibition. Microbes Infect. 2007, 9 (4): 490-497. 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.01.013.

Kuramitsu M, Hashizume C, Yamamoto N, Azuma A, Kamata M, Tanaka Y, Aida Y: A novel role for Vpr of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 as a regulator of the splicing of cellular pre-mRNA. Microbes Infect. 2005, 7 (9-10): 1150-1160. 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.03.022.

Zhang X, Aida Y: HIV-1 Vpr: a novel role in regulating RNA splicing. Curr HIV Res. 2009, 7 (2): 163-168. 10.2174/157016209787581517.

Andersen JL, Planelles V: The role of Vpr in HIV-1 pathogenesis. Curr HIV Res. 2005, 3 (1): 43-51. 10.2174/1570162052772988.

Le Rouzic E, Benichou S: The Vpr protein from HIV-1: distinct roles along the viral life cycle. Retrovirology. 2005, 2: 11-10.1186/1742-4690-2-11.

Felzien LK, Woffendin C, Hottiger MO, Subbramanian RA, Cohen EA, Nabel GJ: HIV transcriptional activation by the accessory protein, VPR, is mediated by the p300 co-activator. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998, 95 (9): 5281-5286. 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5281.

Goh WC, Rogel ME, Kinsey CM, Michael SF, Fultz PN, Nowak MA, Hahn BH, Emerman M: HIV-1 Vpr increases viral expression by manipulation of the cell cycle: a mechanism for selection of Vpr in vivo. Nat Med. 1998, 4 (1): 65-71. 10.1038/nm0198-065.

Planelles V, Jowett JB, Li QX, Xie Y, Hahn B, Chen IS: Vpr-induced cell cycle arrest is conserved among primate lentiviruses. J Virol. 1996, 70 (4): 2516-2524.

Stivahtis GL, Soares MA, Vodicka MA, Hahn BH, Emerman M: Conservation and host specificity of Vpr-mediated cell cycle arrest suggest a fundamental role in primate lentivirus evolution and biology. J Virol. 1997, 71 (6): 4331-4338.

Zimmerman ES, Chen J, Andersen JL, Ardon O, Dehart JL, Blackett J, Choudhary SK, Camerini D, Nghiem P, Planelles V: Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr-mediated G2 arrest requires Rad17 and Hus1 and induces nuclear BRCA1 and gamma-H2AX focus formation. Mol Cell Biol. 2004, 24 (21): 9286-9294. 10.1128/MCB.24.21.9286-9294.2004.

Zimmerman ES, Sherman MP, Blackett JL, Neidleman JA, Kreis C, Mundt P, Williams SA, Warmerdam M, Kahn J, Hecht FM, Grant RM, de Noronha CM, Weyrich AS, Greene WC, Planelles V: Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr induces DNA replication stress in vitro and in vivo. J Virol. 2006, 80 (21): 10407-10418. 10.1128/JVI.01212-06.

McGowan CH, Russell P: The DNA damage response: sensing and signaling. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004, 16 (6): 629-633. 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.09.005.

Le Rouzic E, Belaidouni N, Estrabaud E, Morel M, Rain JC, Transy C, Margottin-Goguet F: HIV1 Vpr arrests the cell cycle by recruiting DCAF1/VprBP, a receptor of the Cul4-DDB1 ubiquitin ligase. Cell Cycle. 2007, 6 (2): 182-188.

Angers S, Li T, Yi X, MacCoss MJ, Moon RT, Zheng N: Molecular architecture and assembly of the DDB1-CUL4A ubiquitin ligase machinery. Nature. 2006, 443 (7111): 590-593.

He YJ, McCall CM, Hu J, Zeng Y, Xiong Y: DDB1 functions as a linker to recruit receptor WD40 proteins to CUL4-ROC1 ubiquitin ligases. Genes Dev. 2006, 20 (21): 2949-2954. 10.1101/gad.1483206.

Higa LA, Wu M, Ye T, Kobayashi R, Sun H, Zhang H: CUL4-DDB1 ubiquitin ligase interacts with multiple WD40-repeat proteins and regulates histone methylation. Nat Cell Biol. 2006, 8 (11): 1277-1283. 10.1038/ncb1490.

Jin J, Arias EE, Chen J, Harper JW, Walter JC: A family of diverse Cul4-Ddb1-interacting proteins includes Cdt2, which is required for S phase destruction of the replication factor Cdt1. Mol Cell. 2006, 23 (5): 709-721. 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.08.010.

Belzile JP, Duisit G, Rougeau N, Mercier J, Finzi A, Cohen EA: HIV-1 Vpr-mediated G2 arrest involves the DDB1-CUL4AVPRBP E3 ubiquitin ligase. PLoS Pathog. 2007, 3 (7): e85-10.1371/journal.ppat.0030085.

DeHart JL, Zimmerman ES, Ardon O, Monteiro-Filho CM, Arganaraz ER, Planelles V: HIV-1 Vpr activates the G2 checkpoint through manipulation of the ubiquitin proteasome system. Virol J. 2007, 4: 57-10.1186/1743-422X-4-57.

Hrecka K, Gierszewska M, Srivastava S, Kozaczkiewicz L, Swanson SK, Florens L, Washburn MP, Skowronski J: Lentiviral Vpr usurps Cul4-DDB1[VprBP] E3 ubiquitin ligase to modulate cell cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007, 104 (28): 11778-11783. 10.1073/pnas.0702102104.

Schrofelbauer B, Hakata Y, Landau NR: HIV-1 Vpr function is mediated by interaction with the damage-specific DNA-binding protein DDB1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007, 104 (10): 4130-4135. 10.1073/pnas.0610167104.

Wen X, Duus KM, Friedrich TD, de Noronha CM: The HIV1 protein Vpr acts to promote G2 cell cycle arrest by engaging a DDB1 and Cullin4A-containing ubiquitin ligase complex using VprBP/DCAF1 as an adaptor. J Biol Chem. 2007, 282 (37): 27046-27057. 10.1074/jbc.M703955200.

Dehart JL, Planelles V: Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr links proteasomal degradation and checkpoint activation. J Virol. 2008, 82 (3): 1066-1072. 10.1128/JVI.01628-07.

Muthumani K, Zhang D, Hwang DS, Kudchodkar S, Dayes NS, Desai BM, Malik AS, Yang JS, Chattergoon MA, Maguire HC, Weiner DB: Adenovirus encoding HIV-1 Vpr activates caspase 9 and induces apoptotic cell death in both p53 positive and negative human tumor cell lines. Oncogene. 2002, 21 (30): 4613-4625. 10.1038/sj.onc.1205549.

Stewart SA, Poon B, Jowett JB, Xie Y, Chen IS: Lentiviral delivery of HIV-1 Vpr protein induces apoptosis in transformed cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999, 96 (21): 12039-12043. 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12039.

Siddiqui K, Del Valle L, Morellet N, Cui J, Ghafouri M, Mukerjee R, Urbanska K, Fan S, Pattillo CB, Deshmane SL, Kiani MF, Ansari R, Khalili K, Roques BP, Reiss K, Bouaziz S, Amini S, Srinivasan A, Sawaya BE: Molecular mimicry in inducing DNA damage between HIV-1 Vpr and the anticancer agent, cisplatin. Oncogene. 2008, 27 (1): 32-43. 10.1038/sj.onc.1210632.

McCray AN, Ugen KE, Heller R: Enhancement of anti-melanoma activity of a plasmid expressing HIV-1 Vpr delivered through in vivo electroporation. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007, 6 (8): 1269-1275.

McCray AN, Ugen KE, Muthumani K, Kim JJ, Weiner DB, Heller R: Complete regression of established subcutaneous B16 murine melanoma tumors after delivery of an HIV-1 Vpr-expressing plasmid by in vivo electroporation. Mol Ther. 2006, 14 (5): 647-655. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.06.010.

Azuma A, Matsuo A, Suzuki T, Kurosawa T, Zhang X, Aida Y: Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr induces cell cycle arrest at the G(1) phase and apoptosis via disruption of mitochondrial function in rodent cells. Microbes Infect. 2006, 8 (3): 670-679. 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.09.002.

Nishizawa M, Kamata M, Katsumata R, Aida Y: A carboxy-terminally truncated form of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr protein induces apoptosis via G(1) cell cycle arrest. J Virol. 2000, 74 (13): 6058-6067. 10.1128/JVI.74.13.6058-6067.2000.

Morellet N, Bouaziz S, Petitjean P, Roques BP: NMR structure of the HIV-1 regulatory protein VPR. J Mol Biol. 2003, 327 (1): 215-227. 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00060-3.

Le Rouzic E, Morel M, Ayinde D, Belaidouni N, Letienne J, Transy C, Margottin-Goguet F: Assembly with the Cul4A-DDB1DCAF1 ubiquitin ligase protects HIV-1 Vpr from proteasomal degradation. J Biol Chem. 2008, 283 (31): 21686-21692. 10.1074/jbc.M710298200.

Zhao LJ, Mukherjee S, Narayan O: Biochemical mechanism of HIV-I Vpr function. Specific interaction with a cellular protein. J Biol Chem. 1994, 269 (22): 15577-15582.

Nishizawa M, Kamata M, Mojin T, Nakai Y, Aida Y: Induction of apoptosis by the Vpr protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 occurs independently of G(2) arrest of the cell cycle. Virology. 2000, 276 (1): 16-26. 10.1006/viro.2000.0534.

Nishizawa M, Myojin T, Nishino Y, Nakai Y, Kamata M, Aida Y: A carboxy-terminally truncated form of the Vpr protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 retards cell proliferation independently of G(2) arrest of the cell cycle. Virology. 1999, 263 (2): 313-322. 10.1006/viro.1999.9905.

Nishino Y, Myojin T, Kamata M, Aida Y: Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr gene product prevents cell proliferation on mouse NIH3T3 cells without the G2 arrest of the cell cycle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997, 232 (2): 550-554. 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6186.

Cormack BP, Valdivia RH, Falkow S: FACS-optimized mutants of the green fluorescent protein (GFP). Gene. 1996, 173 (1 Spec No): 33-38. 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00685-0.

Gey GO, Coffman WD, Kubicek MT: Tissue culture studies of the proliferative capacity of cervical carcinoma and normal epithelium. Cancer Res. 1952, 12 (4): 264-265.

Goldstein MN, Slotnick IJ, Journey LJ: In vitro studies with HeLa cell line sensitive and resistant to actinomycin D. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1960, 89: 474-483. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1960.tb20171.x.

DuBridge RB, Tang P, Hsia HC, Leong PM, Miller JH, Calos MP: Analysis of mutation in human cells by using an Epstein-Barr virus shuttle system. Mol Cell Biol. 1987, 7 (1): 379-387.

Aden DP, Fogel A, Plotkin S, Damjanov I, Knowles BB: Controlled synthesis of HBsAg in a differentiated human liver carcinoma-derived cell line. Nature. 1979, 282 (5739): 615-616. 10.1038/282615a0.

Knowles BB, Howe CC, Aden DP: Human hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines secrete the major plasma proteins and hepatitis B surface antigen. Science. 1980, 209 (4455): 497-499. 10.1126/science.6248960.

R-Development-Core-Team: R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2008, Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2.8

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the Viral Infectious Diseases Unit for helpful comments and suggestions. This study was supported, in part, by a Health Sciences Research Grant from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan (Research on HIV/AIDS) and by the program for Promotion of Fundamental Studies in Health Sciences of the National Institute of Biomedical Innovation (NIBIO) of Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

MN participated in the all experiments and drafted the manuscript. YH carried out the immunoassay, analysis of the cell cycle, measurements of caspase activity and helped to draft the manuscript. ST performed the statistical analysis, measured Annexin V-positive cells and helped to draft the manuscript. YA conceived of the study, and participated in its design, and coordination of experiments, and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Nonaka, M., Hashimoto, Y., Takeshima, Sn. et al. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr protein and its carboxy-terminally truncated form induce apoptosis in tumor cells. Cancer Cell Int 9, 20 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2867-9-20

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2867-9-20