Abstract

Background

Bacteria possess a reservoir of metabolic functionalities ready to be exploited for multiple purposes. The use of microorganisms to clean up xenobiotics from polluted ecosystems (e.g. soil and water) represents an eco-sustainable and powerful alternative to traditional remediation processes. Recent developments in molecular-biology-based techniques have led to rapid and accurate strategies for monitoring and identification of bacteria and catabolic genes involved in the degradation of xenobiotics, key processes to follow up the activities in situ.

Results

We report the characterization of the response of an enriched bacterial community of a 1,2-dichloroethane (1,2-DCA) contaminated aquifer to the spiking with 5 mM lactate as electron donor in microcosm studies. After 15 days of incubation, the microbial community structure was analyzed. The bacterial 16S rRNA gene clone library showed that the most represented phylogenetic group within the consortium was affiliated with the phylum Firmicutes. Among them, known degraders of chlorinated compounds were identified. A reductive dehalogenase genes clone library showed that the community held four phylogenetically-distinct catalytic enzymes, all conserving signature residues previously shown to be linked to 1,2-DCA dehalogenation.

Conclusions

The overall data indicate that the enriched bacterial consortium shares the metabolic functionality between different members of the microbial community and is characterized by a high functional redundancy. These are fundamental features for the maintenance of the community's functionality, especially under stress conditions and suggest the feasibility of a bioremediation treatment with a potential prompt dehalogenation and a process stability over time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Ecological models and experimental data suggest that taxonomic diversity and genetic-functional redundancy are key factors in increasing the flexibility of microbial communities that subsequently can both perform a given metabolic function more efficiently and better overcome metabolic stresses [1–3]. Biodiversity is linked to both the chemical-physical characteristics of the environment and the dynamic and synergistic interactions between microbes that in turn contribute to determine the level of ecosystem functioning [4–6]. The ecological behavior of microbes together with their enormous metabolic potential is a valuable solution to remediation of polluted environments [7–12]. The exploitation of the enormous metabolic capabilities associated with microorganisms has been recently defined as Microbial Resource Management (MRM): bacteria can be seen as cell factories that are stirred to produce or degrade a given compound under human management [13].

Among major anthropogenic pollutants, chlorinated aliphatics and aromatics are of great concern especially in anaerobic environments like groundwater and sediments where they tend to accumulate. For example, 1,2-dichloroethane (1,2-DCA) is considered a priority pollutant, being the most abundant double-carbon chlorinated compound contaminating the groundwater worldwide [14, 8]. Literature reports several examples on how microbial metabolic potential can enhance the removal of 1,2-DCA [10–12] as well as of other chlorinated alkanes and alkenes [8, 15–17]. Key enzymes implicated in the dechlorination processes are the reductive dehalogenases (RDs), a class of enzymes capable of eliminating chlorine from molecules [18–24].

In our previous study, RD sequences correlated with 1,2-DCA dechlorination to ethene have been identified in Desulfitobacterium dichloroeliminans strain DCA1 (RD DCA1) - a microorganism that can efficiently dechlorinate 1,2-DCA using hydrogen as electron donor - and in situ in a 1,2-DCA contaminated aquifer (RD 54) [12, 25]. The enrichment culture setup from the aquifer (culture 6VS), was reported to contain both Dehalobacter and Desulfitobacterium spp. Recently three novel RDs sequences (WL rdhA1, WL rdhA2 and WL rdhA3) have been identified in a 1,2-DCA dehalogenating enrichment culture containing Dehalobacter sp. WL [26]. In the present work, the 6VS mixed culture [25] was structurally and functionally characterized after transferring in fresh anaerobic microcosms amended with 1,2-DCA and lactate as electron donor. The final aim was to describe the response of the resident microbial community, in terms of species diversity and functional redundancy, in order to foresee a biostimulation or a bioaugmentation treatment to solve the problem in situ.

Results

Bacterial diversity

We recently described a groundwater aquifer with a historical contamination by 1,2-DCA that held dechlorinating microorganisms [12, 25]. The bacterial dehalogenating consortium was maintained through adhesion of the original culture to an active-carbon support [25] and used to set up a new microcosm. The microbial community was incubated for 15 days, in anaerobic conditions, in presence of 5 mM of lactate as electron donor and 900 mg L-1 of 1,2-DCA. Following lactate amendment, the 1,2-DCA was completely dechlorinated in about 260 h (11 days). To evaluate the presence in the microbial community of species potentially involved in the 1,2-DCA degradation, we examined the diversity of microbial communities by establishing 16S rRNA gene clone libraries. PCR with specific primers for archaea did not give any amplicon, even after a second round of PCR using nested primers.

The overall community diversity as a function of both the total number of species present (richness) and their relative distribution (evenness) was calculated from the data obtained from the bacterial 16S rRNA gene libraries after lactate amendment. The diversity and structure of bacterial community was analyzed using three indices: 1) Species richness, that is the number of species identified in a sample; 2) Simpson's index, that is the probability that two clones, taken at random from a sample, will be the same species. This measure is sensitive to changes in the frequency of the more abundant species; 3) Shannon-Wiener index, that reflects the diversity and the evenness of clones distribution between taxa. It is sensitive to changes in the frequency of common and less common (though not the rarer) species [27]. After the treatment, the bacterial community of the enrichment culture was characterized by a relatively high species richness (12 species), with a Simpson index of 0.781 and a Shannon index of 1.807. Pareto-Lorenz curve was used as a graphical estimator of the species evenness [28, 29]. The operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were ranked from high to low, based on their relative abundance within the library. The cumulative normalized number of clones was used as X-axis, and their respective cumulative proportion of abundances was reported in the Y-axis (Figure 1A). Following the treatment, Pareto-Lorenz curves showed a situation where 20% of the OTUs represented 65-70% of the total abundance of clones.

Pareto-Lorenz distribution of bacterial diversity. Pareto-Lorenz distribution curve of the microbial community's evenness after the biostimulation treatment. The 45° diagonal represents a perfect evenness of a community. The black arrow indicates the OTU cumulative proportion of abundances for an OTU cumulative proportion of 0.2.

A summary of the clones identified in the libraries is shown in Table 1. The 12 OTUs are reported with the percent distribution normalized by rRNA gene copy numbers from the closest phylogenetic relatives, in order to minimize the rRNA copy number bias [30]. Rarefaction curves to saturation indicated that microbial diversity in the library was satisfactorily covered (data not shown). The bacterial clone libraries were dominated by sequences related to Desulfitobacterium, Dehalobacter and Clostridium genera, in the Firmicutes phylum. In particular the most abundant sequences were those identified having a 97% similarity with Desulfitobacterium dichloroeliminans strain DCA1 and a 99% similarity with Dehalobacter sp. WL (26 clones for each sequence over a total of 88 clones). Both these bacteria have been reported to dechlorinate 1,2-DCA to ethene [25, 26]. Hence, the microbial community resulted to be dominated by few species (Figure 1A) and most of them are potentially related to the degradation of chlorinated compounds (Figure 1B). Other numerically relevant clones were related to Desulfitobacterium metallireducens and to Trichlorobacter thiogenes.

Functional genes diversity

In order to evaluate the functional redundancy of the resident microbial community in response to biostimulation with lactate, the reductive dehalogenase diversity was investigated. For this purpose, functional gene libraries of this class of enzymes were prepared starting from the total DNA extracted from the microcosm. Primers PceAFor1 and DcaB rev, annealing upstream and downstream the gene dcaA, were used to amplify the variable region of the dcaABCT gene cluster coding for the reductive dehalogenase [25]. A total of 39 clones were sequenced and sequences were aligned with those from previously characterized RD. The phylogenetic relationship among the different RDs found in the groundwater is shown in Figure 2. Four groups (I-IV) of RDs could be identified. Most of the clones were affiliated to groups I and III, while groups II and IV were represented by only two clones each. A high proportion of clones (24 over a total of 39) clustered in group I and were closely related to the RD previously identified in D. dichloroeliminans strain DCA1 (RD DCA1) and in the same contaminated site (RD 54) (the nucleotide identity was higher than 98%). The sequence UP-RD-6', representing the RD group II, was related to the RD of the strain DCA1 but with a lower nucleotide identity (96%). A third group, including the sequences of eleven clones, presented only a 94% and a 88-89% identity at respectively nucleotide and amino acid level with the DcaA catalytic subunit previously identified in the same aquifer [25]. On the contrary, these sequences had an amino acid identity between 98 and 99% with WL rdhA1, one of the three RDs sequences recently identified by Grostern and colleagues [26] in Dehalobacter sp. WL.

RDs sequences phylogenetic tree. Neighbour-joining tree with branch lengths to assess the relationship between DcaA of a previously characterized RD from the contaminated aquifer (RD-54) [Accession number: AM183919] and of D. dichloroeliminans strain DCA1 (RD-DCA1) [AM183918] with other A subunits of already characterized RDs, PceA of Dehalobacter restrictus strain DSMZ 9455T (RD-TCE D. restrictus) [AJ439607], Desulfitobacterium hafniense strain TCE1 (RD-TCE D. hafniense) [AJ439608] and Desulfitobacterium sp. strain Y51 (PCE-D.Y51) [AY706985]. Besides, are also reported the recently identified WL RdhA1, WL RdhA2 and WL RdhA3 [FJ010189, FJ010190, FJ010191] and the RDs identified in enrichment culture (UP RD X). The numbers at each node represent percentage of bootstrap calculated from 1000 replicate trees. The scale bar represents the sequence divergence.

It has been previously shown that 53% of the total amino acid diversity of DcaA of the RD-54 and RD-DCA1, when aligned with PceA of RDs specific for tetrachloroethene (PCE) from Dehalobacter restrictus strain DSMZ 9455T [31], Desulfitobacterium sp. strain Y51 [21], and Desulfitobacterium hafniense strain PCE-S [20], was mainly localized in two small regions (blocks A and B - Figure 3) that represent only 19% (104 amino acids over 551) of the total DcaA residues [25]. These two regions of hyper-variability were proposed to be involved in 1,2-DCA recognition or in general in the substrate specificity of RDs [25]. The novel RDs sequences, identified in this work, were aligned to WL rdhA1 and to sequences of the previously mentioned RDs specific for PCE. From the alignment it was possible to identify two hyper-variable regions overlapping with blocks A and B (Figure 3). In particular we focused our attention on the RDs sequences of groups I and III, considering the higher number of clones in these two clusters. Within blocks A and B of the selected RDs sequences, as well in other smaller regions of the DcaA subunit, it was possible to identify amino acids specific for: i) PceA, the RDs specific for PCE (yellow residues); ii) DcaA of group III, an RD from Dehalobacter proposed to be specific for 1,2-DCA (light blue residues), iii) DcaA of the group I, an RD from Desulfitobacterium, proposed to be specific for 1,2-DCA (dark grey residues), iv) all the RDs within the groups I and III but not for PCE-specific RDs (green residues).

Amino acid alignment of the DcaA proteins. Amino acid alignment of the DcaA proteins of groups I (UP-RD-A) and III (UP-RD-4 and UP-RD-G) of the new identified RDs, with: those previously identified in the groundwater (RD-54), in D. dichloroeliminans strain DCA1 (D.d. DCA1) [Accession number AM183919 and AM183918], with PceA of Desulfitobacterium sp. strain Y51 (D. Y51) [AY706985], D. hafniense strain TCE1 (D.h.) [AJ439608], D. restrictus strain DSMZ 9455T (D.r.) [AJ439607], and with the recently identified WL rdhA1 (WL-RdhA1) [FJ010189]. Only the regions including amino acid variations among the different proteins are presented. Red rectangles A and B indicate the protein stretches where it has been previously indicated that resides 53% of the total amino acid diversity between DcaA and PceA [25]. Light blue residues are amino acids specific for the DcaA of the group III, proposed to be specific for the 1,2-DCA RD from Dehalobacter; dark grey residues those specific for the DcaA subunit of the group I, proposed to be specific for the 1,2-DCA RD from Desulfitobacterium; green residues those common to all the RDs identified in the aquifers contaminated by 1,2-DCA but not conserved in the PCE-specific RDs. Asterisks, colons and dots below the alignment indicate an identical position in all the proteins, a position with a conservative substitution and a position with a semi-conservative substitution, respectively.

Discussion

The stability of microbial communities has been suggested to correlate not only to the number of species occupying a niche but also to the functional redundancy found in the same niche [32, 33]. Under this concept, microbial communities should be more flexible if the same function prevails under varying environmental conditions and is supported by enzymes adapted to the different conditions the microbial community is exposed to. In this study, a reductive dechlorination activity was linked to an adapted and specialized bacterial community that presented, after suitable stimulation, a high functional redundancy. According to the three diversity indexes (species richness, Simpson and Shannon index) and the Pareto Lorenz curve representation, the bacterial community is characterized by a good richness and few dominant species. Following the interpretation reported by Marzorati and colleagues [29], the structure of the studied microbial community (the 20% of the OTUs represent the 65-70% of the total abundance of clones) can be considered typical of a specialized community (as an enriched microbial community should be). The 16S rRNA gene clone library showed that the 1,2-DCA-degrading consortium was equally dominated by two different taxa related to Desulfitobacterium dichloroeliminans strain DCA1 and Dehalobacter sp. WL., previously shown to be involved in the 1,2-DCA reductive dechlorination. In other studies different bacteria within the same microbial community were shown to exhibit specific activities towards different chlorinated congeners [34]. Coherently with our results, Grostern and colleagues [35] described the co-growth of more microorganisms competing for the same chlorinated compound. As suggested by the authors, the co-growth probably occurs due to the presence of slightly different niches for each bacteria that avoid their direct competition. We hypothesize that the differences in niche partitioning in our culture are due to the presence of a suitable and not limiting growth substrate and electron donor. This enrichment conditions enhanced the growth of those portion of the microbial community that might function as a flexible reservoir of various degraders of halogenated compounds.

The third most abundant OTU was related to Desulfitobacterium metallireducens, identified for the first time by Finneran and colleagues [36] in an uranium-contaminated aquifer. Desulfitobacterium metallireducens was described as an anaerobic bacterium able to couple its growth to the reduction of metals, humic acids and chlorinated compounds (trichloroethylene or tetrachloroethylene) using lactate as electron donor [36]. However its involvement in 1,2-DCA dehalogenation was not demonstrated. The co-growth in dechlorinating enrichment cultures of bacteria not directly related to the dehalogenating activity but with an indirect role in the process is commonly reported in literature [37, 38, 26]. This is supported also by the identification of sequences related to Lactobacillus sp. and Zymophilus sp., species known to be able to produce lactate and other organic acids useful as electron donors for the reductive dechlorination process. The structure and composition of the microbial community suggested that the positive response to the treatment is possibly led by a 'complementarity effect' rather than a 'selection effect' [2].

A further sign of the 'complementarity effect' was the identification of possible functional redundancy related to 1,2-DCA reductive dechlorination. The RDs gene clone library showed four different RDs enzymes, all conserving signature residues possibly linked to 1,2-DCA dehalogenation [25, 26]. Two main groups of RDs (cluster I and III) characterized the consortium and it was possible to connect the presence of these functional genes to the two most abundant OTUs identified in the 16S rRNA gene library. Sequences belonging to the group I were associated to Desulfitobacterium dichloroeliminans strain DCA1, that showed the same amino acid signatures in the two reductive dehalogenases in its genome [25]. Sequences of the group III most likely belonged to Dehalobacter. In fact, taking into account that i) rdhA1 of Dehalobacter sp. WL was found in a culture amended with only 1,2-DCA; ii) its abundance was shown to be correlated with both Dehalobacter growth and 1,2-DCA dechlorination activity; and that iii) Dehalobacter sp. WL rdhA1 transcription occurred upon exposure to 1,2-DCA, Grostern and colleagues [26] concluded that rdhA1 represents a putative Dehalobacter 1,2-DCA RD gene. At the moment, regarding the RDs sequences of the groups II and IV, we have no definitive proof or literature data supporting their involvement in any specific dehalogenation process.

Finally, the occurrence of Dehalobacter sp. WL rdhA2 and rdhA3 in similar abundances in a 1,1,2-TCA-amended culture was correlated to a second Dehalobacter strain that uses 1,1,2-TCA and, to a lesser extent, 1,2-DCA [26]. Our findings could support this hypothesis, with strain WL rdhA3 that clusters together rdhA1 in group III (Figure 2) and rdhA2 completely separated from any other cluster and thus possibly not involved in 1,2-DCA degradation.

Conclusions

The capacity of sharing metabolic functionalities between different members of a microbial community is a fundamental feature for the efficiency of a microbial community, especially under stress conditions. In fact, when a given species cannot stand the environmental fluctuations, the community functional stability is assured by the presence of other species capable of performing the same function [29, 33]. This is of special interest for bioremediation treatments when normally the microbial communities have to face harsh environmental conditions with the potential toxic effect of the pollutant and the low availability of one or more carbon sources, electron donors or nutrients.

Here we showed the characterization of a 1,2-DCA degrading microbial consortium, providing the concept that microbial metabolism can be exploited to solve real practical problems (MRM).

Upon several sub-culturing steps providing 1,2-DCA and lactate as electron donor, we were able to enrich a microbial community that could degrade up to 900 ppm of 1,2-DCA in less then 15 days. This community was dominated by bacteria belonging to the Firmicutes phylum. Among them, the most abundant OTUs were related to Desulfitobacterium dichloroeliminans strain DCA1 and Dehalobacter sp. WL, two strains known to be able to reductively dechlorinate 1,2-DCA to ethene with no other toxic intermediate metabolite. The structure of the microbial community was also correlated to functional redundancy with the identification of four phylogenetically-distinct catalytic enzymes, all conserving signature residues possibly linked to 1,2-DCA dehalogenation.

In MRM terms, the application of lactate represents a possible solution to boost the potential of the autochthonous microbial community for the degradative activity. On the other side, the enriched consortium itself is a potential candidate inoculum for bioaugmentation purposes to support groundwater remediation when such metabolic capabilities are not naturally present [39]. Further studies are needed for the in situ validation of these principles.

Methods

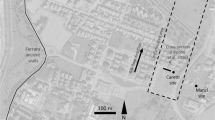

Establishment of enrichment culture

Anaerobic microcosms were prepared with groundwater from an aquifer contaminated for more than 30 years by 1,2-DCA, as described by Marzorati and colleagues [12]. The groundwater was contaminated with 1,2-DCA at a high concentration (up to 900 mg L-1), but not by other chlorinated ethanes or ethenes. The bacterial dehalogenating consortium was maintained through adhesion of the original culture to an active-carbon support and the microcosms were prepared in an anaerobic box incubated under N2/CO2/H2 (80/15/5%) at room temperature (average temperature 22°C) and fed with 5 mM Na lactate and additional 1,2-DCA. The medium was prepared as previously reported by Marzorati and colleagues [12].

The concentrations of 1,2-DCA, ethene, vinyl chloride and other possible degradation products in the microcosms were analyzed by head-space gas chromatography, on a 7694 Agilent gas chromatograph equipped with a flame ionization detector set at 200°C on a DB624 column (J&W Scientific, Folsom, CA) at constant oven temperature at 80°C. 1,2-DCA limit of detection was 1 μg L-1.

PCR amplification of 16S rRNA and reductive dehalogenase genes

DNA from the enrichment culture was extracted, starting from 1.5 mL of suspension, as previously described [40]. 16S rRNA gene were amplified using bacterial universal primers 27f (5'AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG 3') and 1494r (5'CTACGGCTACCTTGTTACGA 3') with the following reaction: 1× PCR buffer (Invitrogen, Milan, Italy), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.12 mM of each dNTP, 0.3 μM of each primer, 1 U of Taq polymerase in a final volume of 50 μL. Initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min was followed by 5 cycles consisting of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 50°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 2 min, and by 30 cycles consisting of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 55°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 2 min. A final extension at 72°C for 10 min was added.

A region of the reductive dehalogenase gene cluster including all dcaA and 194 bp of dcaB gene was amplified using primers PceAFor1 (5' ACGTGCAATTATTATTAAGG3') and DcaB rev (5'TGGTATTCACGCTCCGA3'), as reported by Marzorati and colleagues [25].

16S rRNA and functional genes libraries construction

Sixty ng PCR product (insert:vector molar ratio of 3:1) was used for cloning reactions using the pGEM cloning kit (pGEM-T Easy Vector Systems, Promega, Milan, Italy) following the recommendations of the manufacturer. A direct PCR assay was performed on white colonies to amplify the insert using primers T7 (3'CTAATACGACTCACTATAGGG 5') and SP6 (3'ATTTAGGTGACACTATAGAATA 5'). Amplification reactions were performed in a 25 μL total volume containing, 1× reaction buffer (Invitrogen), 0.12 mM of each dNTP, 0.7 U of Taq DNA polymerase, 0.3 μM of each primer. Reactions were performed with the following protocol: an initial melting at 94°C for 4 min, followed by 30 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 50°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1.5 min and a final extension step at 72°C for 5 min. PCR products were purified by a QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Milan, Italy) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Clones from bacterial 16S rRNA gene library were sequenced with primer 27f, those from RD libraries with the primer PceAFor1, using the ABI Prism BigDye terminator cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Milan, Italy) and an ABI 310 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Rarefaction curves were built using the PAST program [41]. To determine the Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) the 99% identity criterion for the full-length 16S rRNA sequence has been chosen to minimize underestimation of the true functional diversity of the ecosystem [42] and to minimize PCR artifacts due to Taq DNA polymerase errors [43]. Two clones per each OTU were completely sequenced using primer 1494r for bacterial 16S rRNA gene libraries and DcaB rev and DHLF3 (5' GAAATAGCTAATGAGCCTGT 3') for RD gene libraries.

Statistical analysis

The closest relative match to each sequence was obtained with BLASTN facilities [44] and Classifier v.6.0 program at the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) 10 http://rdp.cme.msu.edu/classifier/classifier.jsp[45]. Chimera sequences were checked with the chimera-check tool at greengenes.lbl.gov [46]. Sequences were phylogenetically aligned using ClustalW software http://clustalw.genome.ad.jp/[47]. Alignments were checked manually and corrected for any misalignments that had been generated. Tree construction was done with Treecon v.1.3b using neighbor-joining methods and a bootstrap analysis with 1000 replicates. Matrix similarities among 16S rRNA sequences and RDs sequences were calculated in Phylip Interface using Jukes-Cantor algorithm for DNA and Dayhoff PAM matrix for protein sequences.

The following indices were calculated by using the PAST program [41] to give a more detailed description of the diversity within the samples [48]: Dominance (D = Σpi2), Shannon (H = -Σ(pi) × (logepi) and Simpson (Ds = 1-D), where pi is the ratio between the abundance of each OTU and the total number of clones analyzed. In order to graphically represent the evenness of the bacterial communities, Pareto-Lorenz distribution curves [28] were set up based on the 16S rRNA gene clone library results as reported by Marzorati and colleagues [29].

Sequence accession number

The nucleotide sequences of the clones identified in this study were deposited in the EMBL nucleotide sequence database (GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ) under the accession numbers from FM204994 to FM205005 for bacterial 16S rRNA genes and from FM204935 to FM204942 for RD sequences.

References

Loreau M, Hector A: Partitioning selection and complementarity in biodiversity experiments. Nature. 2001, 412: 72-76. 10.1038/35083573.

Cardinale BJ, Palmer MA, Collins SL: Species diversity enhances ecosystem functioning through interspecific facilitation. Nature. 2002, 415: 426-429. 10.1038/415426a.

Fernandez AS, Hashsham SA, Dollhopf SL, Raskin L, Glagoleva O, Dazzo FB, Hickey RF, Criddle CS, Tiedje JM: Flexible community structure correlates with stable community function in methanogenic bioreactor communities perturbed by glucose. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000, 66: 4058-4067. 10.1128/AEM.66.9.4058-4067.2000.

Bell T, Newman JA, Silverman BW, Turner SL, Lilley AK: The contribution of species richness and composition to bacterial services. Nature. 2005, 436: 1157-1160. 10.1038/nature03891.

Carrero-Colón M, Nakatsu CH, Konopka A: Effect of nutrient periodicity on microbial community dynamics. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006, 72: 3175-3183. 10.1128/AEM.72.5.3175-3183.2006.

Konopka A: Microbial ecology: searching for principles. Microbe. 2006, 1: 175-179.

Watanabe K, Futamata H, Harayama S: Understanding the diversity in catabolic potential of microorganisms for the development of bioremediation strategies. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2002, 81: 655-663. 10.1023/A:1020534328100.

Field JA, Sierra-Alvarez R: Biodegradability of chlorinated solvents and related chlorinated aliphatic compounds. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol. 2004, 3: 185-254. 10.1007/s11157-004-4733-8.

Widada J, Nojiri H, Omor T: Recent developments in molecular techniques for identification and monitoring of xenobiotic-degrading bacteria and their catabolic genes in bioremediation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002, 60: 45-59. 10.1007/s00253-002-1072-y.

Klecka GM, Carpenter CL, Gonsior SJ: Biological transformation of 1,2-dichloroethane in subsurface soils and groundwater. J Contam Hydrol. 1998, 34: 139-154. 10.1016/S0169-7722(98)00096-5.

Nobre RCM, Nobre MMM: Natural attenuation of chlorinated organics in a shallow sand aquifer. J Haz Mat. 2004, 110: 129-137. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2004.02.046.

Marzorati M, Borin S, Brusetti L, Daffonchio D, Marsilli C, Carpani G, de Ferra F: Response of 1,2-dichloroethane-adapted microbial communities to ex-situ biostimulation of polluted groundwater. Biodegradation. 2006, 17: 41-56. 10.1007/s10532-005-9004-z.

Verstraete W: Microbial ecology and environmental biotechnology. ISME J. 2007, 1: 4-8. 10.1038/ismej.2007.7.

Hughes K, Meek ME, Caldwell I: 1,2-dichloroethane: evaluation of risks and health from environmental exposure in Canada. Environ Carcinog Rev. 1994, 12: 293-303.

Lendvay JM, Löffler FE, Dollhopf M, Aiello MR, Daniels G, Fathepure BZ, Gebhard M, Heine R, Helton R, Shi J, Krajmalnik-Brown R, Major CL, Barcelona MJ, Petrovskis E, Hickey R, Tiedje JM, Adriaens P: Bioreactive barriers: bioaugmentation and biostimulation for chlorinated solvent remediation. Environ Sci Technol. 2003, 37: 1422-1431. 10.1021/es025985u.

Macbeth TW, Cummings DE, Spring S, Petzke LM, Sorenson KS: Molecular characterization of a dechlorinating community resulting from in situ biostimulation in a trichloroethene-contaminated deep, fractured basalt aquifer and comparison to a derivative laboratory culture. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004, 70: 7329-7341. 10.1128/AEM.70.12.7329-7341.2004.

Major DW, McMaster ML, Cox EE, Edwards EA, Dworatzek SM, Hendrickson ER, Starr MG, Payne JA, Buonamici LW: Field demonstration of successful bioaugmentation to achieve dechlorination of tetrachloroethene to ethene. Environ Sci Technol. 2002, 36: 5106-5116. 10.1021/es0255711.

Waller AS, Krajmalnik-Brown R, Löffler FE, Edwards EA: Multiple reductive-dehalogenase-homologous genes are simultaneously transcribed during dechlorination by Dehalococcoides-containing cultures. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005, 71: 8257-8264. 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8257-8264.2005.

Kube M, Beck A, Zinder SH, Kuhl H, Reinhardt R, Adrian L: Genome sequence of the chlorinated compound - respiring bacterium Dehalococcoides species strain CBDB1. Nat Biotechnol. 2005, 23: 1269-1273. 10.1038/nbt1131.

Maillard J, Regeard C, Holliger C: Isolation and characterization of Tn -Dha1, a transposon containing the tetrachloroethene reductive dehalogenase of Desulfitobacterium hafniense strain TCE1. Environ Microbiol. 2005, 7: 107-117. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2004.00671.x.

Suyama A, Yamashita M, Yoshino S, Furukawa K: Molecular characterization of the PceA reductive dehalogenase of Desulfitobacterium sp. strain Y51. J Bacteriol. 2002, 184: 3419-3425. 10.1128/JB.184.13.3419-3425.2002.

Sanford RA, Cole JR, Löffler FE, Tiedje JM: Characterization of Desulfitobacterium chlororespirans sp. nov., which grows by coupling the oxidation of lactate to the reductive dechlorination of 3-chloro-4-hydroxybenzoate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996, 62: 3800-3808.

Smidt H, de Vos WM: Anaerobic microbial dehalogenation. Ann Rev Microbiol. 2004, 58: 43-73. 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123600.

Holliger C, Wohlfarth G, Diekert G: Reductive dechlorination in the energy metabolism of anaerobic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1999, 22: 383-398. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1998.tb00377.x.

Marzorati M, de Ferra F, Van Raemdonck H, Borin S, Allifranchini E, Carpani G, Serbolisca L, Verstraete W, Boon N, Daffonchio D: A novel reductive dehalogenase, identified in a contaminated groundwater enrichment and in Desulfitobacterium dichloroeliminans strain DCA1, is linked to dehalogenation of 1,2-dichloroethane. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007, 73: 2990-2999. 10.1128/AEM.02748-06.

Grostern A, Edwards EA: A characterization of a Dehalobacter coculture that dechlorinates 1,2-dichloroethane to ethene and identification of the putative reductive dehalogenase gene. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009, 75: 2684-2693. 10.1128/AEM.02037-08.

Johnson A, Llewellyn N, Smith J, Gast van der C, Lilley A, Singer A, Thompson I: The role of microbial community composition and groundwater chemistry in determining isoproturon degradation potential in UK aquifers. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2004, 40: 71-82.

Lorenz MO: Methods of measuring concentration of wealth. J Am Stat Assoc. 1905, 9: 209-219.

Marzorati M, Wittebolle L, Boon N, Daffonchio D, Verstraete W: How to get more out of molecular fingerprints: practical tools for microbial ecology. Environ Microbiol. 2008, 10: 1571-1581.

Bedard DL, Ritalahti KM, Loffler FE: The Dehalococcoides population in sediment-free mixed cultures metabolically dechlorinates the commercial polychlorinated biphenyl mixture Aroclor 1260. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007, 73: 2513-2521. 10.1128/AEM.02909-06.

Maillard J, Schumacher W, Vazquez F, Regeard C, Hagen WR, Holliger C: Characterization of the corrinoid iron-sulfur protein tetrachloroethene reductive dehalogenase of Dehalobacter restrictus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003, 69: 4628-4638. 10.1128/AEM.69.8.4628-4638.2003.

McArthur JV: Microbial Ecology: An Evolutionary Approach. 2006, Oxford: Academic Press

Wittebolle L, Marzorati M, Clement L, Balloi A, Daffonchio D, Heylen K, De Vos P, Verstraete W, Boon N: Initial community evenness favours functionality under selective stress. Nature. 2009, 458: 623-626. 10.1038/nature07840.

Fagervold Sonja SK, May HD, Sowers KR: Microbial reductive dechlorination of Aroclor 1260 in Baltimore harbor sediment microcosms is catalyzed by three phylotypes within the phylum Chloroflexi. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007, 73: 3009-3018. 10.1128/AEM.02958-06.

Grostern A, Edwards EA: Growth of Dehalobacter and Dehalococcoides spp. during degradation of chlorinated ethanes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006, 72: 428-436. 10.1128/AEM.72.1.428-436.2006.

Finneran KT, Forbush HM, Gaw Van Praagh CV, Lovley DR: Desulfitobacterium metallireducens sp. nov., an anaerobic bacterium that couples growth to the reduction of metals and humic acids as well as chlorinated compounds. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2002, 52: 1929-1935. 10.1099/ijs.0.02121-0.

De Wildeman S, Diekert G, Van Langenhove H, Verstraete W: Stereoselective microbial dehalorespiration with vicinal dichlorinated alkanes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003, 69: 5643-5647. 10.1128/AEM.69.9.5643-5647.2003.

Watts JEM, Fagervold SK, May HD, Sowers KR: A PCR-based specific assay reveals a population of bacteria within the Chloroflexi associated with the reductive dehalogenation of polychlorinated biphenyls. Microbiology. 2005, 15: 2039-2046. 10.1099/mic.0.27819-0.

Maes A, Van Raemdonck H, Smith K, Ossieur W, Lebbe L, Verstraete W: Transport and activity of Desulfitobacterium dichloroeliminans strain DCA1 during bioaugmentation of 1,2-DCA-contaminated groundwater. Environ Sci Technol. 2006, 40: 5544-5552. 10.1021/es060953i.

Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K: Current protocols of molecular biology. 1994, John Wiley and Sons, New York

Hammer Ø, Harper DAT, Ryan PD: PAST: Paleontological Statistics Software Package for Education and Data Analysis. Palaentol Electron. 2001, 4: 1-9.

Edwards JE, McEwan NR, Travis AJ, Wallace RJ: 16S rDNA library-based analysis of ruminal bacterial diversity. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2004, 86: 263-281. 10.1023/B:ANTO.0000047942.69033.24.

Acinas SG, Sarma-Rupavtarm R, Klepac-Ceraj V, Polz MF: PCR-induced sequence artifacts and bias: insights from comparison of two 16S rRNA clone libraries constructed from the same sample. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005, 71: 8966-8969. 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8966-8969.2005.

Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ: Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990, 215: 403-410.

Maidak BL, Cole JR, Parker CT, Garrity GM, Larsen , Li B, Lilburn TG, McCaughey MJ, Olsen GJ, Overbeek R, Pramanik S, Schmidt TM, Tiedje JM, Woese CR: A new version of the RDP (Ribosomal Database Project). Nucleic Acids Research. 1999, 27: 171-173. 10.1093/nar/27.1.171.

DeSantis TZ, Hugenholtz P, Keller K, Brodie EL, Larsen N, Piceno YM, Phan R, Andersen GL: NAST: a multiple sequence alignment server for comparative analysis of 16S rRNA genes. Nucleic Acids Research. 2006, 34: W394-399. 10.1093/nar/gkl244.

Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ: CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Research. 1994, 22: 4673-4680. 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673.

Magurran AE: Ecological diversity and its measurement. 1988, Princeton University Press

Meijer WG, Nienhuis-Kuiper ME, Hansen TA: Fermentative bacteria from estuarine mud: phylogenetic position of Acidaminobacter hydrogenoformans and description of a new type of gram-negative, propionigenic bacterium as Propionibacter pelophilus gen. nov., sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999, 3: 1039-1044.

De Wever H, Cole JR, Fettig MR, Hogan DA, Tiedje JM: Reductive dehalogenation of trichloroacetic acid by Trichlorobacter thiogenes gen. nov., sp. nov. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000, 66: 2297-2301. 10.1128/AEM.66.6.2297-2301.2000.

Ueki A, Akasaka H, Suzuki D, Ueki K: Paludibacter propionicigenes gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel strictly anaerobic, Gram-negative, propionate-producing bacterium isolated from plant residue in irrigated rice-field soil in Japan. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2006, 56: 39-44. 10.1099/ijs.0.63896-0.

Murray AE, Preston CM, Massana R, Taylor TL, Blakis A, Wu K, Delong EF: Seasonal and spatial variability of bacterial and archaeal assemblages in the coastal waters near Anvers Island, Antarctica. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998, 64: 2585-2595.

Ravot G, Magot M, Fardeau ML, Patel BKC, Thomas P, Garcia JL, Ollivier B: Fusibacter paucivorans gen. nov., sp. nov., an anaerobic, thiosulfate-reducing bacterium from an oil-producing well. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999, 49: 1141-1147.

Hallin PF, Ussery D: CBS Genome Atlas Database: a dynamic storage for bioinformatic results and sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2004, 20: 3682-3686. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth423.

Bedard DL, Bailey JJ, Reiss BL, Jerzak GV: Development and characterization of stable sediment-free anaerobic bacterial enrichment cultures that dechlorinate Aroclor 1260. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006, 72: 2460-2470. 10.1128/AEM.72.4.2460-2470.2006.

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by a grant from Eni S.p.A. Divisione Refining & Marketing as part of the project "Caratterizzazione microbiologica e molecolare di siti contaminati da idrocarburi clorurati" (Contratto n. 4800040841). We also thank Lorenzo Brusetti for the advice with statistical analyses.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

DD, FdF and WV planned the work that led to the manuscript; MM, AB and LC produced and analyzed the experimental data; LW and GC participated in the interpretation of the results; MM, AB and DD wrote the paper; WV and FdF participated in the revision of manuscript's intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Marzorati, M., Balloi, A., de Ferra, F. et al. Bacterial diversity and reductive dehalogenase redundancy in a 1,2-dichloroethane-degrading bacterial consortium enriched from a contaminated aquifer. Microb Cell Fact 9, 12 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2859-9-12

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2859-9-12