Abstract

Streptomyces, the main antibiotic-producing bacteria, responds to changing environmental conditions through a complex sensing mechanism and two-component systems (TCSs) play a crucial role in this extraordinary “sensing” device.

Moreover, TCSs are involved in the biosynthetic control of a wide range of secondary metabolites, among them commercial antibiotics. Increased knowledge about TCSs can be a powerful asset in the manipulation of bacteria through genetic engineering with a view to obtaining higher efficiencies in secondary metabolite production. In this review we summarise the available information about Streptomyces TCSs, focusing specifically on their connections to antibiotic production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microorganisms included in the genus Streptomyces are Gram-positive bacteria that inhabit soil niches, thus facing ever changing environmental conditions and nutrient scarcity [1]. Along evolution, this challenging environment has pushed the genus Streptomyces towards complex adaptive responses. Among them, two-component systems (TCSs) are the most important transduction signal mechanism in bacteria, allowing the translation of these rapid environmental or nutritional changes into a regulatory readout [2, 3]. Typically, TCSs comprise a membrane-bound histidine kinase (HK), which senses specific environmental stimuli, and a cognate regulator (RR), which mediates the cellular response, mainly through the transcriptional regulation of target genes [4].

Bacteria belonging to the genus Streptomyces harbour a high number of TCSs in comparison with other bacterial genera, probably due to the changing environment that these organisms must inhabit. As an example, the genome sequence of the model S. coelicolor has revealed an unprecedented proportion of regulatory genes (approximately 12.3% of the total ORFs); [5, 6]. Table 1 summarizes the number of TCSs in all Streptomyces species sequenced at the time of writing (P2CS: http://www.p2cs.org).

The competitiveness of these bacteria for resources is also increased due to the production of a large number of secondary metabolites with different activities such as fungicides, cytostatics, modulators of the immune response, and plant growth effectors [1, 7]. Henceforth, all these compounds will be grouped under the name “antibiotics” in order to simplify the review. Almost half of all known antibiotics are produced by actinomycetes, mostly Streptomyces[1, 8, 9], including two-thirds of the clinically useful antibiotics [10]. For example, S. coelicolor produces three chromosomally encoded antibacterial compounds: actinorhodin (ACT), undecylprodiginine (RED) and calcium dependent antibiotic (CDA). More recently, a yellow pigment (yCPK) associated with a type I polyketide synthase cluster (cpk) has also been described [11, 12]. However, its genome contains the information necessary to potentially encode more than twenty secondary metabolites, most of them as yet undetected. Many silenced pathways have been observed in all the Streptomyces genomes sequenced to date, indicating the high biosynthetic potential of these organisms [13, 14].

Antibiotic production responds to stress situations (mainly nutrient starvation) in coordination with primary metabolic responses [15]. Accordingly, Streptomyces needs to finely modulate such production, depending mostly on the primary metabolic flux and availability of both nutrients and precursors for these antibiotics [16].

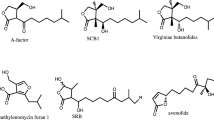

Such a complex network of antibiotic regulation is controlled at two main levels. At the lower level, the cluster-situated regulators (CSRs), located within the antibiotic biosynthetic clusters, can modulate the antibiotic biosynthetic genes of the cluster in which they are included, and according to recent data they can also regulate the expression of genes located distant from them [17]. So far, in S. coelicolor five CSRs have been elucidated: ActII-ORF4 [18], RedD/RedZ [19, 20], KasO (also designated CpkO) [21] and CdaR [22], which are responsible for the biosynthesis of ACT, RED, yCPK and CDA respectively. At the upper level, pleiotropic regulators have been shown to control the production of more than one antibiotic. In Streptomyces, the most abundant pleiotropic regulators are the TCSs, a significant fraction of which regulates antibiotic production and morphological differentiation. (Orphan regulators such as RedZ with a role in antibiotic production have also been described but we will just focus here in “traditional TCS” with a cognate histidine kinase). TCSs regulators can act by direct binding to CSRs promoters or can act indirectly, through other regulatory pathways. Only a few binding sequences of S.coelicolor TCSs regulators to CSRs promoters have been described to date. These binding motifs are shown in Figure 1.

Location of the binding sequences for the S. coelicolor response regulators AfsQ1, DraR in the promoter regions of antibiotic cluster-situated regulators: actII-ORF4 , redZ , kasO , and cdaR[23, 24]. Transcription starting points are indicated with an arrow. -10 and −35 sites and translation start codon are also shown.

Broadening our knowledge of the involvement of TCSs in the regulation of antibiotic synthesis can contribute to the rational design of new hyper-producer host strains through genetic manipulation of these complex systems. Moreover, strategies involving TCSs can be used to unveil new antimicrobial molecules that are not produced under laboratory conditions. Some excellent broadly-based reviews regarding general antibiotic regulation in Streptomyces[15, 16, 25–28] and describing TCSs in Streptomyces[29] have been published. Here, we summarise current knowledge regarding the involvement of TCS in antibiotic biosynthesis in the model streptomycete S. coelicolor, describing how each TCS affects antibiotic biosynthesis and providing some examples of their present applications and their possibilities for the future improvement of antibiotic production and discovery.

To date, the activating signals of most TCSs remain unknown. In light of the available knowledge about the signal triggering the system, we shall divide the review between TCSs with known signals and TCSs whose signals have not been studied and/or that remain unknown. TCSs with unknown signals will in turn be divided between TCSs that regulate the production of a single antibiotic, TCSs that regulate the production of more than one antibiotic, and the regulators responsible for controlling antibiotic production and morphological differentiation. In order to facilitate our understanding of this complex network of interactions, Figure 2 shows updated information regarding which of the S. coelicolor TCSs plays a role in the production of each antibiotic and how these regulatory processes work.

Schematic overview of the regulation of antibiotic production by the TCSs described in this review. A) TCSs with a known signal (Nitrogen, N, or phosphate, P). B) TCSs with an unknown signal. (+) Indicates positive regulation; (−) indicates negative regulation. Straight arrows indicate that the regulation is exerted through the CSRs. A double-lined arrow indicates that regulation is exerted indirectly, and not through CSRs. The intermediate targets of the indirect regulation are shown, in a box within the arrows, when known. A discontinuous line indicates that the regulation mechanism has not yet been studied. The clock indicates timing control in antibiotic biosynthesis.

Review

TCSs with known activating signals

Coupling nitrogen availability and antibiotic production: the AfsQ1/2 and DraR/K systems

The AfsQ1/Q2 system was initially identified due to the ability of a S. coelicolor fragment containing afsQ1 to confer the capacity to produce pigmented antibiotics when introduced into a plasmid in S. lividans, whose antibiotic gene clusters are usually silenced in most culture conditions [30]. Nevertheless, a deletion mutant of the S. coelicolor afsQ1 and afsQ2 genes (ΔafsQ1/Q2) failed to produce any phenotype when cultivated in rich medium [30], although when grown on defined minimal medium with glutamate as the only carbon source the ΔafsQ1/Q2 mutant showed a decrease in ACT, RED and CDA, antibiotic production [31], indicating the different roles of this system, depending on the culture medium. The complementation of the S. coelicolor double mutant with the regulator (afsQ1) did not restore ACT production, pointing to AfsQ2 kinase as the only phosphorus donor of the response regulator. Although the real signal has not been determined experimentally, a nutritional signal -either an intermediate of nitrogen metabolism or the C/N/P ratio- might act as the trigger of the system.

Regarding the target genes of the AfsQ1 regulator, electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) and quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) experiments revealed that AfsQ1 activates antibiotic biosynthesis by interacting directly with the CSR-genes actII-ORF4, cdaR, and redZ. Moreover, different AfsQ1 binding motifs in the cdaR, redZ and actII-ORF4 promoter regions have been described using Dnase I footprinting assays (Figure 1) [23, 31]. AfsQ1 also activates sigQ, a putative sigma factor that, by acting as a negative regulator of antibiotic production, (sigQ deletion leads to an increase in antibiotic levels) might play a role as an antagonist for the AfsQ1/Q2 system [23].

AfsQ1-binding sequences have been found within the cpkA/cpkD intergenic region and deletion of afsQ1/Q2 led to a substantial reduction of the yellow pigment yCPK [23]. The sequences have also been located in genes with roles in morphological development and carbon, nitrogen and phosphate metabolism, indicating that AfsQ1/Q2 responds to nitrogen excess not only by regulating antibiotic production but also by coordinating the C/N/P balance in the cell through the regulation of genes involved in nitrogen assimilation and phosphorus and carbon uptake [32].

The role of the DraR/K system in the regulation of antibiotics biosynthesis was elucidated in a screening of the TCS gene deletion library using minimal medium (MM) supplemented with different nitrogen sources [24], suggesting an interconnection between the role of AfsQ1/2 and DraR/K in response to nutritional signals.

Deletion of draR/K (and similarly ∆draR and ∆draK single mutants) resulted in a reduction in ACT levels but led to the overproduction of RED when grown in high nitrogen concentrations (mainly glutamine). An increase in the yellow pigment (yCPK) in ΔdraR/K was also observed under the same culture conditions, indicating that the TCS might act as a repressor for RED and yCPK biosynthesis under these circumstances. Thus, the DraR/K system was the first TCS identified that acts differentially in antibiotic biosynthesis in S. coelicolor: it is an activator of ACT and a repressor of RED and yCPK. Scanning electronic microscopy revealed that this TCS was also related to morphological differentiation [24].

qRT-PCR assays confirmed that the deletion of draK/R originates a decrease in the expression of actII-ORF4, the CSR of ACT, and an increase in the expression of kasO, the CSR of yCPK. EMSAs assays with the DraR regulator revealed the direct interaction of the DraR regulator with the upstream regions of actII-ORF4 and kasO through the binding of an 11 bp consensus motif defined using DNase I footprinting assays (Figure 1). In contrast, the increase in RED production observed in the double mutant is not related to a higher expression in redD, the CSR of RED production [24].

Since AfsQ1/Q2, the TCS described above, had a similar pattern of nitrogen-dependent regulation [31], a double mutant ΔdraR/∆afsQ1 was constructed to study the possible coordination between both TCSs in the activation of actII-ORF4. The actII-ORF4 transcript was significantly decreased in the double mutant (ΔdraR/∆afsQ1) as compared with the single mutant (ΔdraR), indicating a possible additive effect between the two systems in the regulation of actII-ORF4 in glutamate-based medium [24].

Similarly to AfsQ1/Q2, the signal that activates the DraR/K system might be a common intermediate generated during nitrogen metabolism or changes in the C/N ratio under the stress of higher concentrations of nitrogen [32]. Further studies addressing the biochemical and biophysical properties of the extracellular sensory domain of DraK have recently shown that conformational changes in this particular domain occur depending on the pH. This change may be involved in signal transduction processes in DraR/DraK TCS [33]. The recent crystallization of the extracellular sensory domain of DraK might provide new clues to unravel the structure and sensing mechanism of DraK kinase [34].

Coordinating phosphate availability and antibiotic production: The PhoP/R system

The TCS PhoP/R is the major signal transduction system for phosphate control in Streptomyces. Under phosphate limitation conditions, this TCS plays an important role, activating pathways for phosphate scavenging and controlling the transition to the stationary phase and secondary metabolism [35, 36]. Its involvement in the control of primary and secondary metabolism in response to phosphate availability was first described in Streptomyces as a result of the search for similarities in the S. lividans genome with the Pho regulon of Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis[37–40]. Under inorganic phosphate limitation, deletion of the gene regulator phoP (ΔphoP) in S. coelicolor resulted in a lower and delayed production of ACT and RED. However, EMSA assays did not reveal any binding of PhoP to the promoter regions of the CSRs actII-ORF4 and redD, suggesting an indirect regulation of antibiotic production [41].

In silico analysis looking for PHO boxes, the target sequences of the PhoP regulator [42, 43], detected a putative binding sequence in the upstream region of the afsS gene, previously described as an activator of both ACT and RED in S. coelicolor[44]. Interestingly, the PhoP-binding sequence determined by footprinting analysis coincided with the binding region previously reported as the binding region of the AfsR regulator that originates competition between both regulators [45]. Luciferase reporter experiments also confirmed that the PhoP regulator not only competes with the AfsR regulator but also acts as a transcriptional repressor of afsS. Additional EMSA assays revealed a reciprocal regulation between both regulators due that AfsR is able to bind the phoRP promoter [41]. In addition, it has been shown that PhoP binds to the promoter of the polymerase omega factor gene rpoZ, required for the biosynthesis of ACT and RED [46]. These data suggest that PhoP indirectly regulates antibiotic production through AfsS and RpoZ. Briefly, PhoR phosphorylates PhoP when phosphate concentrations decrease, and activated PhoP finally produces afsS repression and rpoZ activation, yielding an overall positive regulatory effect on antibiotic production in S. coelicolor[46].

TCSs with unknown activating signals

TCSs regulating the biosynthesis of one antibiotic

CutR/S, SCO0203/0204 and SCO3818 regulating ACT biosynthesis

CutR/S was initially described in S. lividans, being the first TCS described in Gram-positive bacteria of the genus Streptomyces[47]. Gene replacement mutants of cutR and cutS exhibited an accelerated and increased production of ACT in different media.

The involvement of CutR/S in antibiotic production was also demonstrated in S. coelicolor. After the cloning of cutR from S. lividans in this organism, an important repression of ACT production was observed. Therefore, CutR/S also negatively regulates ACT production in S. coelicolor, although no direct binding to actII-ORF4 has been demonstrated. There is no information regarding the activator signal of the system [48].

SCO0203/0204 TCS was studied after the finding of high similarity between the regulator of the TCS, SCO0204, and an orphan regulator, SCO3818. The hypothesis that both regulators might be regulated by the same histidine kinase encoded by SCO0203 was confirmed using trans-phosphorylation analysis [49]. Regarding their role in antibiotic production, both deletion mutants (ΔSCO0203, ΔSCO3818) and the double mutant (ΔSCO0203/0204) showed an earlier and increased ACT production in certain complex media sufficient in Mg2+. In all cases, overproduction could be complemented through the integration of a functional copy of the deleted gene/s. However, the double mutant (ΔSCO0203/0204) could be complemented by a functional copy of SCO0203/0204 or only by a copy of the kinase encoded by SCO0203. The fact that functional complementation of the whole system can be achieved by complementing only with the kinase seems to indicate that there is a functional correlation between the regulator SCO3818 and its potential phosphor donor kinase SCO0203 [49]. Since the phenotype was only evident in complex media sufficient in Mg2+, it is reasonable to speculate that this bivalent cation might act as a signalling molecule to activate the system, although it has not yet been defined as the actual signal itself.

EcrA1/A2 and EcrE1/E2 regulating RED biosynthesis

Microarray analysis revealed two TCSs designated ecrA1/A2[50] and ecrE1/E2[51] in the vicinity of the red locus that are expressed in coordination with the genes of the RED biosynthetic pathway. Single-deletion mutants of both systems, ecrA1/A2 and ecrE1/E2, originated strains with lower RED production than the wild-type strain, while ACT values did not change significantly between the strains tested. In light of this result, both EcrA1/A2 and EcrE1/E2 can be thought to play a role as positive regulators for RED production [50, 51]. ecr genes are also present in other Streptomyces such as S. flavogriseus and S. venezuelae that do not harbour the RED cluster. Therefore, although a coordinated expression of ecrA1/A2 and ecrE1/E2 with RED cluster genes has been described in S. coelicolor, these TCSs should have a different regulatory role in other Streptomyces with no RED biosynthetic pathway.

TCSs controlling the biosynthesis of more than one antibiotic

AbsA1/A2 coordinating antibiotic production

AbsA1/A2 was one of the first TCSs to be related to antibiotic production in S. coelicolor[52]. A screening of mutants produced by UV mutagenesis revealed four mutants blocked in antibiotic production without being affected in morphological differentiation. All of them were mutants in a putative TCS designated AbsA1/2 [52]. Further studies in the mutations that originated the non-antibiotic-producing phenotype revealed point mutations in the transmitter domain of AbsA1 histidine kinase, locking the regulatory system into a negatively regulating mode [53] caused by the lack of phosphatase activity in AbsA1 kinase [54]. Surprisingly, both disruption and deletion mutants at the absA1 and/or absA2 loci originated a precocious hyper production of ACT and RED antibiotics (Pha phenotype), pointing to AbsA1 as the only kinase able to phosphorylate the regulator [52] and to the activated regulator AbsA2-P as a repressor of antibiotic production. Amino acid replacements of D54E, D54A and D54N in AbsA2, which have been described previously as phosphorylation inhibitors, also caused a Pha phenotype in all three mutants [55].

Biochemical studies support the role of AbsA2-P as a repressor of antibiotic production and have demonstrated that the AbsA1 cytoplasmic domain exerts a dual activity and can phosphorylate and dephosphorylate AbsA2. As expected, antibiotic production is dramatically reduced in mutants with enhanced kinase activity and in those with impaired AbsA1 phosphatase activity [54].

The molecular bases for the Pha phenotype were established by AbsA2-P chromatin inmunoprecipitation (ChIP) and revealed that the phosphorylated regulator binds the promoter regions of actII-ORF4, cdaR and redZ, all of them CSRs [56]. In vivo binding targets were confirmed in vitro with EMSA experiments [56].

To gain further insight into the signal response mechanism of the system, kinase transmembrane topology was studied by using different AbsA1 C-terminal deletion fusions to eGFP that positioned the fluorescent protein between each of the five predicted transmembrane domains. The results matched the in silico topological predictions, demonstrating that the AbsA1 kinase has 5 transmembrane domains and a large extracellular C-terminal domain that might be important for response to a hitherto unidentified signal [57].

RapA1/2

A screening of TCSs knock-out mutants in S. coelicolor allowed the isolation of the ΔrapA1/A2 strain, which showed a significant reduction in ACT production but no differences in morphological differentiation or growth on R4C solid medium [58].

Semiquantitative RT-PCRs analysis demonstrated that the expression of actII-ORF4, the CSR of the ACT gene cluster, and the two ACT biosynthetic genes, actIII and actVA5, were clearly reduced in the mutant, suggesting that reduced ACT production may be directly or indirectly dependent on the cluster situated activator actII-ORF4[58].

Proteomic analysis of the knock-out mutant also revealed a lower production of KasO, the CSR of the cryptic polyketide biosynthetic gene cluster (cpk) responsible for yellow pigment (yCPK) production and this result was confirmed by semiquantitative qRT-PCR [58].

TCSs controlling pleiotropic processess

AbrA1/2 and AbrC1/2/3 coordinating growth phase and antibiotic production

The deletion of several TCSs with sequence similarity with the above-described negative regulator AbsA1/2 system allowed the identification of two TCSs with opposite activities. While the ΔabrA1/2 strain displayed a conditional (medium-dependent) increase in antibiotic production and differentiation rates, the deletion of the AbrC1/2/3 (ΔabrC1/2/3) system originated a conditional decrease in differentiation rates and antibiotic production. Therefore, both are pleiotropic regulators being AbrA1/2 negative and AbrC1/2/3 positive regulators respectively [59].

Owing to the presence of two histidine kinases in the vicinity of a regulator, the AbrC1/2/3 system should be considered an atypical two-component system. Moreover, each gene is separated from the upstream ORF by a DNA sequence long enough to harbour its own promoter. Therefore, each gene might be expressed independently in order to fit the different needs of bacteria, although the signals detected by these kinases have not yet been identified. Interestingly, this system is conserved in all Streptomyces species sequenced so far.

Genome-wide ChIP-chip experiments have demonstrated that the AbrC3 protein is able to bind in vivo to the promoter of the CSR of the ACT gene cluster actII-ORF4p, explaining the downregulation of the act cluster observed in the ΔabrC3 strain (Rico et al. unpublished data). However, no direct binding of the regulator to the RED and CDA CSRs was observed, suggesting an indirect regulation of these pathways.

The signal or signals triggering kinase phosphorylation remain unknown. Since the phenotypes are medium-dependent, a signal that is only present in certain media seems to be necessary for the system to be activated. An alternative explanation might be that in culture media in which no change in phenotype was observed other regulatory systems could be active, perhaps masking AbrC1/2/3 activity.

SCO5784/5785: controlling the timing of sporulation and antibiotic production

This TCS was originally studied because it shares a certain degree of homology with the B. subtilis degS-degU operon that influences protein secretion and the timing and level of antibiotic production [60, 61]. ACT synthesis occurs later in the deficient strain than in the wild-type, while the propagation of multicopy SCO5785 results in a higher production of ACT at earlier stages relative to the wild-type strain. An equivalent result was observed when RED was measured. It was also seen that sporulation was delayed when the level of the regulator gene decreased, whereas its overproduction caused early sporulation [62]. As expected, transcriptomic analysis revealed an up-regulation of the ACT and RED CSRs actII-ORF4 and redZ respectively in the overproducer strain and a downregulation in the deficient strain. In this case, the TCS seems to respond to environmental inputs, modulating the timing of both antibiotic production as well as sporulation, and controlling the transition from primary to secondary metabolism [62].

Engineering S. coelicolor TCS to improve antibiotic biosynthesis

The emergence of new antibiotic-resistant strains makes the discovery and improvement of the production of new antibiotics major challenges for microbial biotechnology. New tools must be developed to exploit the “hidden biosynthetic potential” available in all Streptomyces genomes sequenced to date [63, 64]. Thus, the sequencing of the S. coelicolor genome [5] has revealed a large number of previously unknown metabolic gene clusters, potential candidates for the production of as yet undiscovered antibiotics and natural products [13]. Among all the possibilities, metabolic engineering using the available knowledge about S. coelicolor TCSs has been used successfully to achieve higher antibiotic production efficiencies and to unveil “cryptic” antibiotics not produced previously under laboratory conditions. Below we briefly summarise some relevant examples.

The information gained about S. coelicolor TCSs has been used in other Streptomyces strains. Homologies with TCSs previously described in S. coelicolor have been found in many other Streptomyces species and could be used as targets to improve antibiotic production. As an example, DraR/K homologues have been found in six Streptomyces strains. The involvement of this system in the biosynthesis of other antibiotics was demonstrated using an S. avermitilis ΔdraR/K strain. Antibiotic production profiles changed dramatically in the deletion mutant as compared to the wild-type strain. Thus, it was observed that DraR-K homologues could be useful targets for the metabolic engineering of Streptomyces species [24]. Reciprocally, information obtained in other Streptomyces strains might be used in S. coelicolor in order to improve antibiotic production.

An alternative strategy that applies the regulatory properties of TCSs is the use of TCS-manipulated strains of S.coelicolor as heterologous hosts in order to hyperproduce different antibiotics or natural products. These strains may be either deletion mutant strains or strains in which a kinase or regulator has been overexpressed, resulting in antibiotic overproduction. Recently, at our laboratory the production of the antitumor drug oviedomycin has been optimized using this kind of approach. This molecule, isolated from S. antibioticus, shows in vitro antitumor activity and induces apoptosis in cancer cell lines [65, 66]. In these experiments the ΔabrA1/A2 strain [59] showed a significant increase in the heterologous production of oviedomycin as compared with the wild-type strain (Santamaria et al., unpublished results). Accordingly, the ΔabrA1/A2 deletion mutant strain might be a good candidate for the heterologous production of natural products. This kind of approach can also be used for the combinatorial biosynthesis of antibiotics. Combinatorial biosynthesis manipulates the genes that encode enzymes in biosynthetic pathways rationally in order to redesign antibiotic structures to create new activities and overcome bacterial resistance to existing antibiotics [67].

A metabolic engineering approach can also be used to unveil cryptic pathways for antibiotic biosynthesis. As mentioned above, some of the first TCSs discovered in S. coelicolor were revealed using a similar approach. AfsQ was initially identified due to its capacity to induce antibiotic production when introduced into the non-antibiotic producer S. lividans[30]. Similar strategies using the overexpression of regulators have been employed successfully in S. coelicolor[68] and other Streptomyces species [69] to discover “hidden” antibiotic synthetic pathways. The expression of wild-type or mutated pleiotropic regulators can be used to create modified streptomycetes in which cryptic biosynthetic genes clusters have been activated. The overexpression of kinases has also been used successfully in S. coelicolor to modify levels of antibiotic production. absA1 alleles previously shown to be antibiotic enhancers in S. coelicolor (see TCS AbsA1/2) were integrated into heterologous Streptomyces to alter its secondary metabolism [70]. New antimicrobial activity was induced in ten streptomycetes and, also as a result of AbsA1 activation, pulvomycin (a broad-spectrum antibiotic) was isolated using this method for the first time in S. flavopersicus[70]. Regarding the mechanism underlying the induction of new antimicrobial activities, as has been reported AbsA2 is a negative regulator of antibiotic production that requires phosphorylation to exert its repression [56]. absA1 alleles could counteract the effects of endogenous AbsA1 protein, dephosphorylating the AbsA2 regulator and therefore allowing the overexpression of totally or partially repressed pathways in Streptomyces species in which AbsA1/2 pleiotropic regulation occurs. Thus, the expression of wild-type or mutated pleiotropic regulators can be used as a screening method to search for new antibiotics and induce silent biosynthetic pathways in Streptomyces.

Another important strategy to decrypt silent pathways in the future might be the use of the proper signals to trigger the TCS activity. As mentioned in previous sections, to date the nature of most of the signals activating S. coelicolor TCSs remains elusive. Their discovery and use in different Streptomyces might offer an important way forward in the discovery of new metabolites with antibiotic properties [71]. In some cases, topology studies (as we report above in the section addressing AbsA1/A2 TCS) can offer relevant information regarding the position of kinases in the membrane and therefore give up some clues about their signal reception. In silico topology predictions of all the kinases described in this review and the conserved domains of both kinases and regulators are shown in Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the topology of the histidine kinases described and their cognate response regulators in S. coelicolor . The putative transmembrane helices were predicted by TopPred-II [74, 75]. Only candidates with a score above 1.0 were considered. The conserved domains and their location are indicated as predicted by PFAM [76].

Conclusions

As discussed above, in recent decades important advances have been made in deciphering the role of TCSs in the regulation of S. coelicolor antibiotic production and some examples of applied knowledge have been described briefly. The emergence of an increasing number of antibiotic-resistant strains has made antibiotic research one of the main priorities in biomedical investigations. Here we have shown how antibiotic production can be improved and how the discovery of new antibiotics can be achieved using on-going research into TCSs. More work needs to be done to study new TCSs in Streptomyces, the connexions between them, and at the same time the whole regulatory system of these interesting microorganisms.

References

Hopwood DA: Streptomyces in Nature and Medicine. The Antibiotic Makers. 2007, New York: Oxford University Press Inc

Krell T, Lacal J, Busch A, Silva-Jimenez H, Guazzaroni ME, Ramos JL: Bacterial sensor kinases: diversity in the recognition of environmental signals. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2010, 64: 539-559. 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134054.

Stock AM, Robinson VL, Goudreau PN: Two-component signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000, 69: 183-215. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.183.

Mascher T, Helmann JD, Unden G: Stimulus perception in bacterial signal-transducing histidine kinases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2006, 70: 910-938. 10.1128/MMBR.00020-06.

Bentley SD, Chater KF, Cerdeño-Tárraga AM, Challis GL, Thomson NR, James KD, Harris DE, Quail MA, Kieser H, Harper D, et al: Complete genome sequence of the model actinomycete Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Nature. 2002, 417: 141-147. 10.1038/417141a.

Hutchings MI, Hoskisson PA, Chandra G, Buttner MJ: Sensing and responding to diverse extracellular signals. Analysis of the sensor kinases and response regulators of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Microbiology. 2004, 150: 2795-2806. 10.1099/mic.0.27181-0.

Omura S: The expanded horizon for microbial metabolites-a review. Gene. 1992, 115: 141-149. 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90552-Z.

Berdy J: Bioactive microbial metabolites. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 2005, 58: 1-26. 10.1038/ja.2005.1.

Berdy J: Thoughts and facts about antibiotics: where we are now and where we are heading. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 2012, 65: 385-395. 10.1038/ja.2012.27.

Papagianni M: Recent advances in engineering the central carbon metabolism of industrially important bacteria. Microb Cell Fact. 2012, 11: 50-10.1186/1475-2859-11-50.

Gomez-Escribano J, Song L, Fox DJ, Yeo V, Bibb MJ, Challis G: Structure and biosynthesis of the unusual polyketide alkaloid coelimycin P1, a metabolic product of the cpk gene cluster of Streptomyces coelicolor M145. Chem Sci. 2012, 3: 2716-2720. 10.1039/c2sc20410j.

Gottelt M, Kol S, Gomez-Escribano JP, Bibb M, Takano E: Deletion of a regulatory gene within the cpk gene cluster reveals novel antibacterial activity in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Microbiology. 2010, 156: 2343-2353. 10.1099/mic.0.038281-0.

Craney A, Ahmed S, Nodwell J: Towards a new science of secondary metabolism. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 2013, 66: 387-400. 10.1038/ja.2013.25.

Sidebottom AM, Johnson AR, Karty JA, Trader DJ, Carlson EE: Integrated metabolomics approach facilitates discovery of an unpredicted natural product suite from Streptomyces coelicolor M145. ACS Chem Biol. 2013, 8: 2009-2016. 10.1021/cb4002798.

Martin JF, Liras P: Engineering of regulatory cascades and networks controlling antibiotic biosynthesis in Streptomyces. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2010, 13: 263-273. 10.1016/j.mib.2010.02.008.

van Wezel GP, McDowall KJ: The regulation of the secondary metabolism of Streptomyces: new links and experimental advances. Nat Prod Rep. 2011, 28: 1311-1333. 10.1039/c1np00003a.

Huang J, Shi J, Molle V, Sohlberg B, Weaver D, Bibb MJ, Karoonuthaisiri N, Lih CJ, Kao CM, Buttner MJ, Cohen SN: Cross-regulation among disparate antibiotic biosynthetic pathways of Streptomyces coelicolor. Mol Microbiol. 2005, 58: 1276-1287. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04879.x.

Arias P, Fernandez-Moreno MA, Malpartida F: Characterization of the pathway-specific positive transcriptional regulator for actinorhodin biosynthesis in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) as a DNA-binding protein. J Bacteriol. 1999, 181: 6958-6968.

Takano E, Gramajo HC, Strauch E, Andres N, White J, Bibb MJ: Transcriptional regulation of the redD transcriptional activator gene accounts for growth-phase-dependent production of the antibiotic undecylprodigiosin in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Mol Microbiol. 1992, 6: 2797-2804. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01459.x.

White J, Bibb M: bldA dependence of undecylprodigiosin production in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) involves a pathway-specific regulatory cascade. J Bacteriol. 1997, 179: 627-633.

Takano E, Kinoshita H, Mersinias V, Bucca G, Hotchkiss G, Nihira T, Smith CP, Bibb M, Wohlleben W, Chater K: A bacterial hormone (the SCB1) directly controls the expression of a pathway-specific regulatory gene in the cryptic type I polyketide biosynthetic gene cluster of Streptomyces coelicolor. Mol Microbiol. 2005, 56: 465-479. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04543.x.

Ryding NJ, Anderson TB, Champness WC: Regulation of the Streptomyces coelicolor calcium-dependent antibiotic by absA, encoding a cluster-linked two-component system. J Bacteriol. 2002, 184: 794-805. 10.1128/JB.184.3.794-805.2002.

Wang R, Mast Y, Wang J, Zhang W, Zhao G, Wohlleben W, Lu Y, Jiang W: Identification of two-component system AfsQ1/Q2 regulon and its cross-regulation with GlnR in Streptomyces coelicolor. Mol Microbiol. 2013, 87: 30-48. 10.1111/mmi.12080.

Yu Z, Zhu H, Dang F, Zhang W, Qin Z, Yang S, Tan H, Lu Y, Jiang W: Differential regulation of antibiotic biosynthesis by DraR-K, a novel two-component system in Streptomyces coelicolor. Mol Microbiol. 2012, 85: 535-556. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08126.x.

Bibb MJ: Regulation of secondary metabolism in streptomycetes. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2005, 8: 208-215. 10.1016/j.mib.2005.02.016.

Liu G, Chater KF, Chandra G, Niu G, Tan H: Molecular regulation of antibiotic biosynthesis in Streptomyces. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2013, 77: 112-143. 10.1128/MMBR.00054-12.

Martin JF, Liras P: Cascades and networks of regulatory genes that control antibiotic biosynthesis. Subcell Biochem. 2012, 64: 115-138. 10.1007/978-94-007-5055-5_6.

Sanchez S, Chavez A, Forero A, Garcia-Huante Y, Romero A, Sanchez M, Rocha D, Sanchez B, Avalos M, Guzman-Trampe S, et al: Carbon source regulation of antibiotic production. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 2010, 63: 442-459. 10.1038/ja.2010.78.

Martín JF, Sola-Landa A, Rodriguez-Garcia A: Two component Systems in Streptomyces. Two-component Systems in Bacteria. Edited by: Gross R, Beier D. 2012, Caister Academic Press

Ishizuka H, Horinouchi S, Kieser HM, Hopwood DA, Beppu T: A putative two-component regulatory system involved in secondary metabolism in Streptomyces spp. J Bacteriol. 1992, 174: 7585-7594.

Shu D, Chen L, Wang W, Yu Z, Ren C, Zhang W, Yang S, Lu Y, Jiang W: afsQ1-Q2-sigQ is a pleiotropic but conditionally required signal transduction system for both secondary metabolism and morphological development in Streptomyces coelicolor. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009, 81: 1149-1160. 10.1007/s00253-008-1738-1.

Martin JF, Sola-Landa A, Santos-Beneit F, Fernandez-Martinez LT, Prieto C, Rodriguez-Garcia A: Cross-talk of global nutritional regulators in the control of primary and secondary metabolism in Streptomyces. Microb Biotechnol. 2011, 4: 165-174. 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2010.00235.x.

Yeo KJ, Kim EH, Hwang E, Han YH, Eo Y, Kim HJ, Kwon O, Hong YS, Cheong C, Cheong HK: pH-dependent structural change of the extracellular sensor domain of the DraK histidine kinase from Streptomyces coelicolor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013, 431: 554-559. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.01.018.

Yeo KJ, Han YH, Eo Y, Cheong HK: Expression, purification, crystallization and preliminary X-ray analysis of the extracellular sensory domain of DraK histidine kinase from Streptomyces coelicolor. Acta Crystallogr Sect F: Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2013, 69: 909-911. 10.1107/S1744309113018769.

Apel AK, Sola-Landa A, Rodriguez-Garcia A, Martin JF: Phosphate control of phoA, phoC and phoD gene expression in Streptomyces coelicolor reveals significant differences in binding of PhoP to their promoter regions. Microbiology. 2007, 153: 3527-3537. 10.1099/mic.0.2007/007070-0.

Martin JF: Phosphate control of the biosynthesis of antibiotics and other secondary metabolites is mediated by the PhoR-PhoP system: an unfinished story. J Bacteriol. 2004, 186: 5197-5201. 10.1128/JB.186.16.5197-5201.2004.

Hulett FM: The signal-transduction network for Pho regulation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1996, 19: 933-939. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.421953.x.

Pragai Z, Harwood CR: Regulatory interactions between the Pho and sigma(B)-dependent general stress regulons of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology. 2002, 148: 1593-1602.

Torriani-Gorini A, Yagil E, Silver S: Phosphate in Microorganisms. Am Soc Microbiol. 1994, Washington, D. C

Sola-Landa A, Moura RS, Martin JF: The two-component PhoR-PhoP system controls both primary metabolism and secondary metabolite biosynthesis in Streptomyces lividans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003, 100: 6133-6138. 10.1073/pnas.0931429100.

Santos-Beneit F, Rodriguez-Garcia A, Sola-Landa A, Martin JF: Cross-talk between two global regulators in Streptomyces: PhoP and AfsR interact in the control of afsS, pstS and phoRP transcription. Mol Microbiol. 2009, 72: 53-68. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06624.x.

Allenby NE, Laing E, Bucca G, Kierzek AM, Smith CP: Diverse control of metabolism and other cellular processes in Streptomyces coelicolor by the PhoP transcription factor: genome-wide identification of in vivo targets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40: 9543-9556. 10.1093/nar/gks766.

Sola-Landa A, Rodriguez-Garcia A, Franco-Dominguez E, Martin JF: Binding of PhoP to promoters of phosphate-regulated genes in Streptomyces coelicolor: identification of PHO boxes. Mol Microbiol. 2005, 56: 1373-1385. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04631.x.

Horinouchi S: AfsR as an integrator of signals that are sensed by multiple serine/threonine kinases in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2003, 30: 462-467. 10.1007/s10295-003-0063-z.

Lee PC, Umeyama T, Horinouchi S: afsS is a target of AfsR, a transcriptional factor with ATPase activity that globally controls secondary metabolism in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Mol Microbiol. 2002, 43: 1413-1430. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02840.x.

Santos-Beneit F, Barriuso-Iglesias M, Fernandez-Martinez LT, Martinez-Castro M, Sola-Landa A, Rodriguez-Garcia A, Martin JF: The RNA polymerase omega factor RpoZ is regulated by PhoP and has an important role in antibiotic biosynthesis and morphological differentiation in Streptomyces coelicolor. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011, 77: 7586-7594. 10.1128/AEM.00465-11.

Tseng HC, Chen CW: A cloned ompR-like gene of Streptomyces lividans 66 suppresses defective melC1, a putative copper-transfer gene. Mol Microbiol. 1991, 5: 1187-1196. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01892.x.

Chang HM, Chen MY, Shieh YT, Bibb MJ, Chen CW: The cutRS signal transduction system of Streptomyces lividans represses the biosynthesis of the polyketide antibiotic actinorhodin. Mol Microbiol. 1996, 21: 1075-1085.

Wang W, Shu D, Chen L, Jiang W, Lu Y: Cross-talk between an orphan response regulator and a noncognate histidine kinase in Streptomyces coelicolor. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009, 294: 150-156. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01563.x.

Li YQ, Chen PL, Chen SF, Wu D, Zheng J: A pair of two-component regulatory genes ecrA1/A2 in S. coelicolor. J Zhejiang Univ (Sci). 2004, 5: 173-179. 10.1631/jzus.2004.0173.

Wang C, Ge H, Dong H, Zhu C, Li Y, Zheng J, Cen P: A novel pair of two-component signal transduction system ecrE1/ecrE2 regulating antibiotic biosynthesis in Streptomyces coelicolor. Biologia. 2007, 62: 511-516. 10.2478/s11756-007-0101-9.

Brian P, Riggle PJ, Santos RA, Champness WC: Global negative regulation of Streptomyces coelicolor antibiotic synthesis mediated by an absA-encoded putative signal transduction system. J Bacteriol. 1996, 178: 3221-3231.

Anderson T, Brian P, Riggle P, Kong R, Champness W: Genetic suppression analysis of non-antibiotic-producing mutants of the Streptomyces coelicolor absA locus. Microbiology. 1999, 145 (Pt 9): 2343-2353.

Sheeler NL, MacMillan SV, Nodwell JR: Biochemical activities of the absA two-component system of Streptomyces coelicolor. J Bacteriol. 2005, 187: 687-696. 10.1128/JB.187.2.687-696.2005.

Anderson TB, Brian P, Champness WC: Genetic and transcriptional analysis of absA, an antibiotic gene cluster-linked two-component system that regulates multiple antibiotics in Streptomyces coelicolor. Mol Microbiol. 2001, 39: 553-566. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02240.x.

McKenzie NL, Nodwell JR: Phosphorylated AbsA2 negatively regulates antibiotic production in Streptomyces coelicolor through interactions with pathway-specific regulatory gene promoters. J Bacteriol. 2007, 189: 5284-5292. 10.1128/JB.00305-07.

McKenzie NL, Nodwell JR: Transmembrane topology of the AbsA1 sensor kinase of Streptomyces coelicolor. Microbiology. 2009, 155: 1812-1818. 10.1099/mic.0.028431-0.

Lu Y, Wang W, Shu D, Zhang W, Chen L, Qin Z, Yang S, Jiang W: Characterization of a novel two-component regulatory system involved in the regulation of both actinorhodin and a type I polyketide in Streptomyces coelicolor. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007, 77: 625-635. 10.1007/s00253-007-1184-5.

Yepes A, Rico S, Rodriguez-Garcia A, Santamaria RI, Diaz M: Novel two-component systems implied in antibiotic production in Streptomyces coelicolor. PLoS One. 2011, 6: e19980-10.1371/journal.pone.0019980.

Mader U, Antelmann H, Buder T, Dahl MK, Hecker M, Homuth G: Bacillus subtilis functional genomics: genome-wide analysis of the DegS-DegU regulon by transcriptomics and proteomics. Mol Genet Genomics. 2002, 268: 455-467. 10.1007/s00438-002-0774-2.

Ogura M, Yamaguchi H, Yoshida K, Fujita Y, Tanaka T: DNA microarray analysis of Bacillus subtilis DegU, ComA and PhoP regulons: an approach to comprehensive analysis of B.subtilis two-component regulatory systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001, 29: 3804-3813. 10.1093/nar/29.18.3804.

Rozas D, Gullon S, Mellado RP: A novel two-component system involved in the transition to secondary metabolism in Streptomyces coelicolor. PLoS One. 2012, 7: e31760-10.1371/journal.pone.0031760.

Medema MH, Breitling R, Bovenberg R, Takano E: Exploiting plug-and-play synthetic biology for drug discovery and production in microorganisms. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011, 9: 131-137. 10.1038/nrmicro2478.

Zerikly M, Challis GL: Strategies for the discovery of new natural products by genome mining. Chembiochem. 2009, 10: 625-633. 10.1002/cbic.200800389.

Lombo F, Braña AF, Salas JA, Mendez C: Genetic organization of the biosynthetic gene cluster for the antitumor angucycline oviedomycin in Streptomyces antibioticus ATCC 11891. Chembiochem. 2004, 5: 1181-1187. 10.1002/cbic.200400073.

Mendez C, Kunzel E, Lipata F, Lombo F, Cotham W, Walla M, Bearden DW, Brana AF, Salas JA, Rohr J: Oviedomycin, an unusual angucyclinone encoded by genes of the oleandomycin-producer Streptomyces antibioticus ATCC11891. J Nat Prod. 2002, 65: 779-782. 10.1021/np010555n.

Walsh CT: Combinatorial biosynthesis of antibiotics: challenges and opportunities. Chembiochem. 2002, 3: 125-134.

Gao C, Hindra , Mulder D, Yin C, Elliot MA: Crp is a global regulator of antibiotic production in Streptomyces. MBio. 2012, 3: e00407-12-

Laureti L, Song L, Huang S, Corre C, Leblond P, Challis GL, Aigle B: Identification of a bioactive 51-membered macrolide complex by activation of a silent polyketide synthase in Streptomyces ambofaciens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011, 108: 6258-6263. 10.1073/pnas.1019077108.

McKenzie NL, Thaker M, Koteva K, Hughes DW, Wright GD, Nodwell JR: Induction of antimicrobial activities in heterologous streptomycetes using alleles of the Streptomyces coelicolor gene absA1. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 2010, 63: 177-182. 10.1038/ja.2010.13.

Sidda JD, Corre C: Gamma-butyrolactone and furan signaling systems in Streptomyces. Methods Enzymol. 2012, 517: 71-87.

Barakat M, Ortet P, Jourlin-Castelli C, Ansaldi M, Mejean V, Whitworth DE: P2CS: a two-component system resource for prokaryotic signal transduction research. BMC Genomics. 2009, 10: 315-10.1186/1471-2164-10-315.

Barakat M, Ortet P, Whitworth DE: P2CS: a database of prokaryotic two-component systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39: D771-776. 10.1093/nar/gkq1023.

Claros MG, von Heijne G: TopPred II: an improved software for membrane protein structure predictions. Comput Appl Biosci. 1994, 10: 685-686.

von Heijne G: Membrane protein structure prediction. Hydrophobicity analysis and the positive-inside rule. J Mol Biol. 1992, 225: 487-494. 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90934-C.

Punta M, Coggill PC, Eberhardt RY, Mistry J, Tate J, Boursnell C, Pang N, Forslund K, Ceric G, Clements J, et al: The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40: D290-301. 10.1093/nar/gkr1065.

Acknowledgements

This work of our laboratory is funded by: Spanish Comisión Interministerial de Ciencia y Tecnología (CICYT) [GEN2003-20245-C09-02]; Junta de Castilla y León (JCyL) [SA072A07, CSI099A12-1]; Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (MICINN) [BFU2010-17551] and Fundación Ramón Areces institutional funding to the IBFG. We thank Sylvia Muñoz for her technical support with figures. S. R. had a JAE-predoctoral grant from the CSIC. H.R. had a postdoctoral fellowship from Botín Foundation. Nicholas Skinner is thanked by the English corrections.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors defined the topic of the review and wrote, read and approved the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Rodríguez, H., Rico, S., Díaz, M. et al. Two-component systems in Streptomyces: key regulators of antibiotic complex pathways. Microb Cell Fact 12, 127 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2859-12-127

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2859-12-127