Abstract

Background

Obesity is a major risk factor for development and progression of hypertension and diabetes, which often coexist in obese patients. Losing weight by means of energy restriction and physical activity has been effective in preventing and managing these diseases. However, weight control behaviors among overweight/obese adults with these conditions are poorly understood.

Methods

Using self-reported data from 143,386 overweight/obese participants (aged ≥ 18 years) in the 2003 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, we examined the proportion of overweight/obese adults who tried to lose weight and their weight control strategies by hypertension and/or diabetes status.

Results

Among all participants, 58% of those with hypertension, 60% of those with diabetes, and 72% of those with both diseases tried to lose weight, significantly higher than the 50% of those with neither condition (Bonferroni corrected P < 0.017 for all comparisons). The multivariate-adjusted odds ratio (AOR) for trying to lose weight was 1.11 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.05–1.17) in participants with hypertension, 1.02 (95% CI: 0.90–1.15) in participants with diabetes, and 1.18 (95% CI: 1.07–1.29) in participants with both diseases (participants with neither condition as the referent). Among 78,446 participants who tried to lose weight, 23% of those with hypertension only and 28% of those with both hypertension and diabetes reported adopting a low fat/low calorie (LF/LC) diet in controlling their weight, significantly higher than 19% of those with neither disease (Bonferroni corrected P < 0.017 for all comparisons). Participants with both diseases had a significantly lower percentage of adopting physical activity in controlling their weight than those with neither condition (6% versus 12%, P < 0.01). After multivariate adjustment, the AOR for adopting a LF/LC diet plus physical activity to lose weight was 1.46 (95% CI: 1.15–1.84) in participants with both diseases. The AOR for adopting a LF/LC diet only to lose weight was 1.72 (95% CI: 1.35–2.20) in participants with both diseases and was 1.21 (95% CI: 1.03–1.40) in participants with hypertension only.

Conclusion

The proportion of overweight/obese patients with diagnosed hypertension and/or diabetes who attempted to lose weight remains suboptimal and the weight control strategies varied significantly among these patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rising trend in overweight and obesity has been a serious and growing public health problem in the United States [1–3]. From 1976–1980 to 2001–2004, the prevalence of overweight/obesity increased by 39% (from 47.4 to 66.0%) and the prevalence of obesity increased by 113% (from 15.1 to 32.1%) [1, 2], the latter has increased slightly to 34.3% during 2005–2006 [4]. Obesity is associated with an increased risk of developing hypertension and diabetes [5–14]. In fact, the prevalence of diagnosed hypertension and diabetes has increased significantly from 1988–1994 to 2001–2004 (21.7% versus 26.7% for hypertension, 5.4% versus 7.3% for diabetes) [1]. In addition, the prevalence of obesity has doubled from 25.7% during 1976–1980 to 50.8% during 1999–2004 among people with hypertension [15]. Moreover, strong associations between a higher body mass index (BMI) and risk of hypertension or diabetes exist even among people within a normal BMI range [9, 16].

A growing body of evidence has shown that losing weight by means of energy restriction and/or increasing physical activity has beneficial effects on the prevention and management of both diseases. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on people with or without hypertension showed that an average weight loss of 5.1 kilograms reduced systolic blood pressure by 4.4 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure by 3.6 mm Hg [17]. Among overweight/obese adults, increasing amount of intentional weight loss was associated with a linear decrease in diabetes incidence [10, 18], and active weight loss is an effective approach to the treatment of people with diabetes [19–22]. Moreover, intentional weight loss is also associated with a significant reduction in all-cause mortality rate in people with or without diabetes [23–26].

Presently, little is known about weight control behaviors among overweight/obese adults with hypertension, diabetes, or both in the U.S. Given an increasing scientific and media attention on the multiple health benefits weight control/weight loss confers, we hypothesized that overweight/obese people with either hypertension or diabetes are more likely to attempt to lose weight (with the highest seen in people with both hypertension and diabetes) compared to people with neither condition. Using data from a nationally representative sample, we examined the proportion of overweight/obese people who attempted to lose weight and their weight control strategies among those with diagnosed hypertension, diabetes or both. We hope this study will increase our understanding concerning weight control behaviors in light of the increasing trends in overweight/obesity, hypertension, and diabetes in the U.S. population.

Methods

Data for our analyses came from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), a population-based telephone survey of health-related behaviors regarding the leading causes of death among noninstitutionalized U.S. adults aged ≥ 18 years. The BRFSS survey design, sampling methods and weights have been described elsewhere [27], and BRFSS data have consistently been found to provide valid and reliable estimates when compared to other national household surveys in the U.S. [27–29]. The survey was reviewed by the Human Research Protection Office at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and determined to be exempt from human subject guidelines. Further information on BRFSS is available at http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/.

In 2003, a total of 149,324 participants who were overweight/obese (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, calculated from self-reported weight and height) were interviewed in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and three U.S. territories of Guam, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. The median cooperation rate (the percentage of eligible persons contacted who completed the interview) was 74.8%.

Respondents' hypertension and diabetes status were assessed by asking them whether they had ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that they had had these conditions. Those who answered that they had not been told they had hypertension (or diabetes) or they had these conditions only during pregnancy were categorized as "no diagnosed hypertension (or diabetes)". Respondents were then categorized as 1) having both hypertension and diabetes, 2) having hypertension only, 3) having diabetes only, and 4) having neither disease. Weight control status was assessed by asking respondents whether they were trying to lose weight. For those who responded with a "yes" to the question, they were further asked whether they were eating less fat and/or fewer calories (defined as a low fat/low calorie [LF/LC] diet) or participating in physical activity or exercise to lose weight. The receipt of doctors' advice on weight loss was assessed by asking respondents whether in the previous 12 months a doctor, nurse or other health professional had given them advice about their weight. Their responses were 1) yes, lose weight; 2) yes, gain weight; 3) yes, maintain current weight; 4) no advice; and 5) don't know/not sure. We treated the first category as "receipt of weight-loss advice" and combined the rest 4 categories into "receipt of no advice on weight loss".

The demographic variables in our analyses included respondents' age, sex, BMI, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and others), education levels (< high school diploma, high school graduate, some college/technical school, and ≥ college graduate), marital status (married, divorced, never married, and others), and employment status (employed for wages, self-employed, unemployed, and retired). Current smokers were those participants who had smoked ≥ 100 cigarettes during their lifetime and were still smoking. Current non-smokers were those who either had smoked <100 cigarettes during their lifetime or had smoked ≥ 100 cigarettes in their entire life but stopped.

After excluding from the analytical sample participants who refused to answer, had missing responses to any questions, or responded "don't know/not sure" to any questions (except for the question on receiving weight-loss advice), a total of 143,386 participants were included in our analyses. The percentages of overweight/obese adults who attempted to lose weight and adopted a LF/LC diet and/or physical activity to lose weight by hypertension and/or diabetes status were weighted to the state populations and age-standardized to the 2000 U.S. population. A Bonferroni corrected P-value (labeled as P value only in the text) was used for multiple comparisons. Logistic regression analyses were conducted to assess the odds ratios for trying to lose weight and for adoption of a LF/LC diet and/or physical activity to lose weight among people with hypertension and/or diabetes using people with neither condition as the referent. We used SUDAAN software (release 9.0, Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC) to account for the multi-stage, disproportionate stratified sampling design.

Results

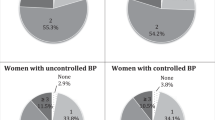

Of all participants, 10,963 had both hypertension and diabetes, 40,666 had hypertension only, 5,143 had diabetes only, and 86,614 had neither condition. Overall, 72.1% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 68.7–75.2%) of those with both hypertension and diabetes, 57.8% (95% CI: 56.4–59.1%) of those with hypertension only, and 60.0% (95% CI: 56.2–63.8%) of those with diabetes only attempted to lose weight, significantly higher than the 49.8% (95% CI: 49.1–50.4%) of those with neither condition (P < 0.017 for all comparisons). The percentages of adults who tried to lose weight also varied significantly by gender and BMI levels (Figure 1 and Table 1). Overweight/obese women had a higher prevalence of trying to lose weight than overweight/obese men did except for those who were obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) and had both hypertension and diabetes concomitantly (i.e., 81% among obese women and men with both conditions). In addition, the prevalence of trying to lose weight increased with age till the age of 50–59 years and thereafter decreased; it was lower in non-Hispanic blacks than in non-Hispanic whites (P = 0.008), and was the lowest in those who were educated at less than a high-school diploma (P < 0.008) and who were current smokers among the selected categories (P < 0.017, Table 1). However, the prevalence of trying to lose weight was significantly higher in participants who received weight-loss advice than in those who did not (P < 0.001).

Among those who attempted to lose weight, 63.5% (95% CI: 62.8–64.2%) of them tried to lose weight by adopting a LF/LC diet and participating in physical activity, 21.0% (95% CI: 20.5–21.6%) by adopting a LF/LC diet only, and 10.9% (95% CI: 10.4–11.4%) by participating in physical activity only (Table 2). Overall, the percentages of adults who adopted a LF/LC diet plus physical activity did not differ significantly by hypertension/diabetes status; however, among those who were overweight, participants with both hypertension and diabetes had the highest prevalence (73.8%, 95% CI: 69.0–78.1%) of adopting a LF/LC diet plus physical activity to lose weight (P < 0.008). In addition, participants either with both hypertension and diabetes (27.6%, 95% CI: 24.4–31.1%) or with hypertension only (23.3%, 95% CI: 21.8–24.8%) had significantly higher percentages of adopting a LF/LC diet in controlling their weight, compared to those with neither condition (19.0%, 95% CI: 18.2–19.7%, P < 0.008 for both comparisons, Table 2). Among those who were overweight, participants with diabetes tended to have a higher prevalence of adopting a LF/LC diet only to lose weight; however, among those who were obese, participants with both hypertension and diabetes had a higher prevalence of adopting a LF/LC diet only than those with diabetes only (30.0% versus 22.0%, P < 0.008) or than those with neither condition (30.0% versus 23.0%, P < 0.008). Overall, participants with both hypertension and diabetes had a lower percentage of participating in physical activity to lose weight than those with hypertension only (6.3% versus 10.2%, P < 0.008) or than those with neither condition (6.3% versus 11.8%, P < 0.008).

Compared to participants with neither disease, participants with either hypertension or diabetes or both were 2.3 to 3.9 times as likely to receive doctors' advice on weight loss (Table 3). However, after adjustment for socio-demographic variables and the receipt of weight-loss advice, only participants with both hypertension and diabetes or with hypertension only were significantly more likely to try to lose weight (Table 3). Among participants who attempted to lose weight, participants with both hypertension and diabetes were significantly more likely to lose weight by adopting a LF/LC diet plus physical activity or by adopting a LF/LC diet only after multivariate adjustment. In addition, participants with hypertension only were significantly more likely to adopt a LF/LC diet to control their weight (Table 3).

Discussion

Our results from a large, population-based survey sample showed that overall, only a little more than half of overweight/obese people tried to lose weight. Although overweight/obese people with hypertension only or with both hypertension and diabetes were 11 to 18% more likely to try to lose weight than those with neither condition, the proportion of these patients who tried to lose weight remains lower (ranged from 58 to 72%) than optimal. In addition, after multivariate adjustment, overweight/obese people with diabetes were not found to be more likely to lose weight than those without. Therefore, a gap remains wide even though the multiple health benefits of weight loss in control of hypertension and diabetes have been demonstrated.

To our knowledge, this is the first large study to examine weight control behaviors in overweight/obese people by hypertension and/or diabetes status. A few earlier studies reported that, during 1996–2000, 24% to 33% of men and 38% to 46% of women in the general U.S. population were trying to lose weight regardless of their BMI levels [30–32]. Among overweight/obese people, 48% of men and 66% of women were trying to lose weight [33]. We have previously reported that 59% of hypertensive women attempted to lose weight [34]. In the present study, we further demonstrated that only 58% to 72% of people with either hypertension or diabetes or both tried to lose weight. Moreover, contrary to expectations, we found that overweight/obese patients with diagnosed diabetes were only as likely as those with neither condition (hypertension and diabetes) to attempt to lose weight after multivariate adjustment for socio-demographic characteristics, smoking status and receipt of doctors' advice on weight loss, suggesting intensive intervention or education programs are needed for diabetes patients.

Weight loss by various strategies significantly reduces body fat mass, blood pressure, fast glucose and hemoglobulin A1c, and improves the 2-h glucose tolerance test, beta-cell function, and insulin sensitivity [17, 19–22, 35–37]. Adequate weight loss can also reduce the requirement (number and doses) of antihypertensive medications or anti-diabetic medications in patients with hypertension and/or diabetes [19–21, 35, 36, 38]. In addition, weight loss produces a favorable lipid profile such as lowering total – and LDL-cholesterol, apolipoprotein B and triglycerides, and increasing HDL-cholesterol level [19, 36, 37, 39], thereby decreasing cardiovascular disease risk in these patients. Thus, weight management is a key strategy in controlling hypertension and diabetes and their complications. It has been shown that behavioral counseling from physicians or other health care providers plays an important role in promoting weight loss in overweigh/obese patients [40–44]. Increased dialogue between diabetes patients and health care providers on behavioral goals significantly increased levels of physical activity and weight loss [40]. In the present study, although overweight/obese patients with either hypertension or diabetes or both were 2 to 4 times as likely as those with neither condition to receive doctors' advice on weight loss, these patients were only 2% to18% more likely to try to lose weight after further adjustment for this variable. This may result from some barriers for weight-loss counseling such as physicians' insufficient confidence, knowledge, and skill on weight management strategies [42]. Moreover, although several studies showed that the proportion of people trying to lose weight increased with increasing level of education in the general population [30–32], which is consistent with the findings of the present study, a study conducted by Gurka et al. reported that patients' educational background differentially affected the lifestyle intervention on weight loss in diabetes control [45]. Diabetes patients with lower educational levels (no college degree) who participated in lifestyle intervention lost more weight or waist circumference than those with higher levels of education (≥ college degree) [45]. In contrast, among usual care participants, patients with less education gained more weight or waist circumference than those with greater education [45]. This suggests that future weight-loss intervention programs or physicians' counseling on weight loss should be individualized in patients with diabetes in order to achieve behavioral goals.

A variety of weight-loss strategies have been implemented in the U.S. population including eating less fat or fewer calories, increasing physical activity or exercise, skipping meals, eating food supplements, taking diet pills, and taking water pills or diuretics [46]. Among those trying to lose weight, reducing fat/calorie intake was the most common strategy [31, 33]. In the present study, two common strategies for weight control – eating less fat/fewer calories and increasing exercise/physical activity were examined. An encouraging finding of our study is that over 60% of overweight/obese patients attempted to lose weight by the combined strategies regardless of their disease status. Patients with both hypertension and diabetes were 46% more likely to lose weight by the combined strategies and 72% more likely to lose weight by eating a low fat/low calorie diet only than those with neither condition. In addition, patients with hypertension were 21% more likely than those with neither condition to lose weight by consuming a low fat/low calorie diet. However, our results indicate that greater weight control efforts are needed among overweight/obese patients with diabetes since, at the national level, we found these patients were not more likely to lose weight, and even in those who attempted to lose weight, they were neither more likely to eat a low fat/low calorie diet nor more likely to engage in physical activity. It is possible that overweight/obese people with diabetes only are not in severe condition so they may think weight management is not imperative in controlling their diabetes. However, given the great benefits of weight loss on improved glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity in people with pre- or newly diagnosed diabetes [37, 47], it is important to educate and encourage these patients to lose excess weight.

Our study has several limitations. First, all measures including weight control behaviors, disease status and BMI were self-reported, thus subject to recall bias. Second, our analyses were based on people with diagnosed hypertension and diabetes; therefore, the prevalence of trying to lose weight in undiagnosed hypertension and diabetes remains unknown. Moreover, as mentioned previously, the less frequent weight-loss strategies such as eating food supplements, taking diet or water pills, or taking diuretics were not evaluated by disease status because of lack of information on these weight control strategies. Those who reported trying to lose weight but neither adopted a low fat/low calorie diet nor engaged in physical activity may have used these strategies. Finally, five years have passed since the data for this analysis were collected (from the 2003 BRFSS). Abid et al. has reported that the proportion of obese persons who reported being counseled by a healthcare professional to lose weight was in a declined trend during the period of 1994–2000 [48]. Thus, updated weight control behaviors should be continuingly monitored at local, state, and national levels.

In summary, the proportion of overweight/obese patients with diagnosed hypertension and/or diabetes who tried to lose weight remains suboptimal and the weight control strategies varied significantly among these patients. Presently, attempting to lose weight is a common health behavior in overweight/obese people; it should be emphasized further in those with various obesity-related chronic comorbidities given the great health benefits of weight loss in controlling these diseases. Our results indicate that great efforts are needed from healthcare providers to interact with their patients to set suitable behavioral goals for weight loss and to provide appropriate education to promote effective weight-loss strategies in these patients. In addition, population-based obesity interventions to promote healthy eating, physical activity and energy balance would benefit all including patients with hypertension and/or diabetes.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

adjusted odds ratio

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- BRFSS:

-

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- DM:

-

diabetes

- HTN:

-

hypertension

- LF/LC:

-

low fat/low calorie.

References

National Center for Health Statistics: Health, United States, 2007, with Chartbook on Trends in the Health of Americans. Hyattsville, MD. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, [http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus07.pdf#listfigures]

National Center for Health Statistics: Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity Among Adults: United States, 2003–2004. [http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/pubs/pubd/hestats/overweight/overwght_adult_03.htm]

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM: Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA. 2006, 295: 1549-1555. 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549.

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, McDowell MA, Flegal KM: Obesity among adults in the United States – no change since 2003–2004. NCHS data brief no 1. 2007, Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, [http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db01.pdf]

Brown CD, Higgins M, Donato KA: Body mass index and the prevalence of hypertension and dyslipidemia. Obes Res. 2000, 8: 605-619. 10.1038/oby.2000.79.

Gregg EW, Cheng YJ, Cadwell BL: Secular trends in cardiovascular disease risk factors according to body mass index in US adults. JAMA. 2005, 293: 1868-1874. 10.1001/jama.293.15.1868.

Huang Z, Willett WC, Manson JE: Body weight, weight change, and risk for hypertension in women. Ann Intern Med. 1998, 128: 81-88.

Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG: Weight change and duration of overweight and obesity in the incidence of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1999, 22: 1266-1272. 10.2337/diacare.22.8.1266.

Gelber RP, Gaziano JM, Manson JE, Buring JE, Sesso HD: A prospective study of body mass index and the risk of developing hypertension in men. Am J Hypertens. 2007, 20: 370-377. 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.10.011.

Colditz GA, Willett WC, Rotnitzky A, Manson JE: Weight gain as a risk factor for clinical diabetes mellitus in women. Ann Intern Med. 1995, 122: 481-486.

Ford ES, Cooper RS: Risk factors for hypertension in a national cohort study. Hypertension. 1991, 18: 598-606.

Garrison RJ, Kannel WB, Stokes J, Castelli WP: Incidence and precursors of hypertension in young adults: the Framingham Offspring Study. Prev Med. 1987, 16: 235-251. 10.1016/0091-7435(87)90087-9.

Wang Y, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Hu FB: Comparison of abdominal adiposity and overall obesity in predicting risk of type 2 diabetes among men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005, 81: 555-563.

Ford ES, Williamson DF, Liu S: Weight change and diabetes incidence: findings from a national cohort of US adults. Am J Epidemiol. 1997, 146: 214-222.

Ford ES, Zhao G, Li C, Pearson WS, Mokdad AH: Trends in obesity and abdominal obesity among hypertensive and nonhypertensive adults in the United States. Am J Hypertens. 2008, 21: 1124-1128. 10.1038/ajh.2008.246.

Williams PT, Hoffman K, La I: Weight-related increases in hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and diabetes risk in normal weight male and female runners. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007, 27: 1811-1819. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.141853.

Neter JE, Stam BE, Kok FJ, Grobbee DE, Geleijnse JM: Influence of weight reduction on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Hypertension. 2003, 42: 878-884. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000094221.86888.AE.

Will JC, Williamson DF, Ford ES, Calle EE, Thun MJ: Intentional weight loss and 13-year diabetes incidence in overweight adults. Am J Public Health. 2002, 92: 1245-1248. 10.2105/AJPH.92.8.1245.

Kelley DE, Bray GA, Pi-Sunyer FX: Clinical efficacy of orlistat therapy in overweight and obese patients with insulin-treated type 2 diabetes: A 1-year randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2002, 25: 1033-1041. 10.2337/diacare.25.6.1033.

Pedersen SD, Kang J, Kline GA: Portion control plate for weight loss in obese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a controlled clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 2007, 167: 1277-1283. 10.1001/archinte.167.12.1277.

Redmon JB, Raatz SK, Reck KP: One-year outcome of a combination of weight loss therapies for subjects with type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2003, 26: 2505-2511. 10.2337/diacare.26.9.2505.

Redmon JB, Reck KP, Raatz SK: Two-year outcome of a combination of weight loss therapies for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005, 28: 1311-1315. 10.2337/diacare.28.6.1311.

Gregg EW, Gerzoff RB, Thompson TJ, Williamson DF: Intentional weight loss and death in overweight and obese U.S. adults 35 years of age and older. Ann Intern Med. 2003, 138: 383-389.

Gregg EW, Gerzoff RB, Thompson TJ, Williamson DF: Trying to lose weight, losing weight, and 9-year mortality in overweight U.S. adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004, 27: 657-662. 10.2337/diacare.27.3.657.

Williamson DF, Thompson TJ, Thun M, Flanders D, Pamuk E, Byers T: Intentional weight loss and mortality among overweight individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2000, 23: 1499-1504. 10.2337/diacare.23.10.1499.

Gelber RP, Kurth T, Manson JE, Buring JE, Gaziano JM: Body mass index and mortality in men: evaluating the shape of the association. Int J Obes (Lond). 2007, 31: 1240-1247. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803564.

Mokdad AH, Stroup DF, Giles WH: Public health surveillance for behavioral risk factors in a changing environment. Recommendations from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Team. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003, 52 (RR-9): 1-12.

Nelson DE, Holtzman D, Bolen J, Stanwyck CA, Mack KA: Reliability and validity of measures from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). Soz Praventivmed. 2001, 46 (Suppl 1): S3-42.

Nelson DE, Powell-Griner E, Town M, Kovar MG: A comparison of national estimates from the National Health Interview Survey and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Am J Public Health. 2003, 93: 1335-1341. 10.2105/AJPH.93.8.1335.

Bish CL, Blanck HM, Serdula MK, Marcus M, Kohl HW, Khan LK: Diet and physical activity behaviors among Americans trying to lose weight: 2000 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Obes Res. 2005, 13: 596-607. 10.1038/oby.2005.64.

Kruger J, Galuska DA, Serdula MK, Jones DA: Attempting to lose weight: specific practices among U.S. adults. Am J Prev Med. 2004, 26: 402-406. 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.02.001.

Serdula MK, Mokdad AH, Williamson DF, Galuska DA, Mendlein JM, Heath GW: Prevalence of attempting weight loss and strategies for controlling weight. JAMA. 1999, 282: 1353-1358. 10.1001/jama.282.14.1353.

Bish CL, Blanck HM, Maynard LM, Serdula MK, Thompson NJ, Khan LK: Health-related quality of life and weight loss practices among overweight and obese US adults, 2003 behavioral risk factor surveillance system. MedGenMed. 2007, 9: 35-40.

Zhao G, Ford ES, Mokdad AH: Racial/ethnic variation in hypertension-related lifestyle behaviours among US women with self-reported hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 2008, 22: 608-616. 10.1038/jhh.2008.52.

Appel LJ, Champagne CM, Harsha DW: Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on blood pressure control: main results of the PREMIER clinical trial. JAMA. 2003, 289: 2083-2093. 10.1001/jama.289.16.2083.

Berne C: A randomized study of orlistat in combination with a weight management programme in obese patients with Type 2 diabetes treated with metformin. Diabet Med. 2005, 22: 612-618. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01474.x.

Shi YF, Pan CY, Hill J, Gao Y: Orlistat in the treatment of overweight or obese Chinese patients with newly diagnosed Type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2005, 22: 1737-1743. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01723.x.

Jones DW, Miller ME, Wofford MR: The effect of weight loss intervention on antihypertensive medication requirements in the hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) study. Am J Hypertens. 1999, 12 (12 Pt 1–2): 1175-1180. 10.1016/S0895-7061(99)00123-5.

Gardner CD, Kiazand A, Alhassan S: Comparison of the Atkins, Zone, Ornish, and LEARN diets for change in weight and related risk factors among overweight premenopausal women: the A TO Z Weight Loss Study: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2007, 297: 969-977. 10.1001/jama.297.9.969.

Christian JG, Bessesen DH, Byers TE, Christian KK, Goldstein MG, Bock BC: Clinic-based support to help overweight patients with type 2 diabetes increase physical activity and lose weight. Arch Intern Med. 2008, 168: 141-146. 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.13.

Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE: Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002, 346: 393-403. 10.1056/NEJMoa012512.

Huang J, Yu H, Marin E, Brock S, Carden D, Davis T: Physicians' weight loss counseling in two public hospital primary care clinics. Acad Med. 2004, 79: 156-161. 10.1097/00001888-200402000-00012.

Loureiro ML, Nayga RM: Obesity, weight loss, and physician's advice. Soc Sci Med. 2006, 62: 2458-2468. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.011.

Galuska DA, Will JC, Serdula MK, Ford ES: Are health care professionals advising obese patients to lose weight?. JAMA. 1999, 282: 1576-1578. 10.1001/jama.282.16.1576.

Gurka MJ, Wolf AM, Conaway MR, Crowther JQ, Nadler JL, Bovbjerg VE: Lifestyle intervention in obese patients with type 2 diabetes: impact of the patient's educational background. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006, 14: 1085-1092. 10.1038/oby.2006.124.

Egger G: Helping patients lose weight – what works?. Aust Fam Physician. 2008, 37: 20-23.

Mensink M, Feskens EJ, Saris WH, De Bruin TW, Blaak EE: Study on Lifestyle Intervention and Impaired Glucose Tolerance Maastricht (SLIM): preliminary results after one year. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003, 27: 377-384. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802249.

Abid A, Galuska D, Khan LK, Gillespie C, Ford ES, Serdula MK: Are healthcare professionals advising obese patients to lose weight? A trend analysis. MedGenMed. 2005, 7: 10-15.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

GZ conducted the data analyses, interpreted the data and prepared the manuscript. ESF supervised the data analyses and contributed to the manuscript writing. CL and AHM made critical revisions of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, G., Ford, E.S., Li, C. et al. Weight control behaviors in overweight/obese U.S. adults with diagnosed hypertension and diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol 8, 13 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2840-8-13

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2840-8-13