Abstract

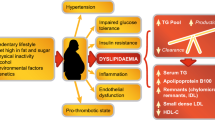

There are three peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) subtypes which are commonly designated PPAR alpha, PPAR gamma and PPAR beta/delta. PPAR alpha activation increases high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol synthesis, stimulates "reverse" cholesterol transport and reduces triglycerides. PPAR gamma activation results in insulin sensitization and antidiabetic action. Until recently, the biological role of PPAR beta/delta remained unclear. However, treatment of obese animals by specific PPAR delta agonists results in normalization of metabolic parameters and reduction of adiposity. Combined treatments with PPAR gamma and alpha agonists may potentially improve insulin resistance and alleviate atherogenic dyslipidemia, whereas PPAR delta properties may prevent the development of overweight which typically accompanies "pure" PPAR gamma ligands. The new generation of dual-action PPARs – the glitazars, which target PPAR-gamma and PPAR-alpha (like muraglitazar and tesaglitazar) are on deck in late-stage clinical trials and may be effective in reducing cardiovascular risk, but their long-term clinical effects are still unknown. A number of glitazars have presented problems at a late stage of clinical trials because of serious side-effects (including ragaglitazar and farglitazar). The old and well known lipid-lowering fibric acid derivative bezafibrate is the first clinically tested pan – (alpha, beta/delta, gamma) PPAR activator. It is the only pan-PPAR activator with more than a quarter of a century of therapeutic experience with a good safety profile. Therefore, bezafibrate could be considered (indeed, as a "post hoc" understanding) as an "archetype" of a clinically tested pan-PPAR ligand. Bezafibrate leads to considerable raising of HDL cholesterol and reduces triglycerides, improves insulin sensitivity and reduces blood glucose level, significantly lowering the incidence of cardiovascular events and new diabetes in patients with features of metabolic syndrome. Clinical evidences obtained from bezafibrate-based studies strongly support the concept of pan-PPAR therapeutic approach to conditions which comprise the metabolic syndrome. However, from a biochemical point of view, bezafibrate is a PPAR ligand with a relatively low potency. More powerful new compounds with pan-PPAR activity and proven long-term safety should be highly effective in a clinical setting of patients with coexisting relevant lipid and glucose metabolism disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) are nuclear hormone receptors, i.e. ligand-dependent intracellular proteins that stimulate transcription of specific genes by binding to specific DNA sequences following activation by the appropriate ligand. When activated, the transcription factors exert several functions in development and metabolism. There are three PPAR subtypes which are the products of distinct genes and are commonly designated PPAR alpha, PPAR gamma and PPAR beta/delta, or merely delta [1–4]. The PPARs usually heterodimerize with another nuclear receptor, the 9-cis-retinoic acid receptor (RXR), forming a complex that interacts with specific DNA response elements within promoter regions of target genes. When activated by agonist ligand binding, this heterodimer complex recruits transcription coactivators and regulates the transcription of genes involved in the control of lipid and carbohydrate metabolism [1–4].

PPAR alpha, activated by polyunsaturated fatty acids and fibrates, is implicated in regulation of lipid metabolism, lipoprotein synthesis and metabolism and inflammatory response in liver and other tissues. PPAR alpha is highly expressed in tissues with high fatty acid oxidation (like liver, kidney and heart muscle), in which it controls a comprehensive set of genes that regulate most aspects of lipid catabolism. Like several other nuclear hormone receptors, it heterodimerizes with RXR alpha to form a transcriptionally competent complex [1–3, 5]. In addition, PPAR-alpha is expressed in vascular endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, monocyte/macrophages and T lymphocytes. PPAR alpha activation increase HDL cholesterol synthesis, stimulate "reverse" cholesterol transport and reduce triglycerides [1–3, 6].

PPAR gamma plays important roles in the regulation of proliferation and differentiation of several cell types, including adipose cells. It has the ability to bind a variety of small lipophilic compounds derived from both metabolism and nutrition. These ligands, in turn, determine cofactor recruitment to PPAR gamma, regulating the transcription of genes in a variety of complex metabolic pathways. PPAR gamma is highly expressed in adipocytes, where it mediates differentiation, promotes lipid storage, and, as a consequence, is thought to indirectly improve insulin sensitivity and enhance glucose disposal in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle [7–9]. Its activation by drugs of the glitazones (thiazolidinediones) group results in insulin sensitization and antidiabetic action.

Until recently, the biological role of PPAR delta remained unclear. Animal studies revealed that PPAR delta play an important role in the metabolic adaptation of several tissues to environmental changes. Treatment of obese animals by specific PPAR delta agonists results in normalization of metabolic parameters and reduction of adiposity. PPAR delta appeared to be implicated in the regulation of fatty acid burning capacities of skeletal muscle and adipose tissue by controlling the expression of genes involved in fatty acid uptake, beta-oxidation and energy uncoupling. PPAR delta is also implicated in the adaptive metabolic response of skeletal muscle to endurance exercise by controlling the number of oxidative myofibers, inducing so and enhancing fatty acid catabolism in muscular tissue [3, 6, 10]. Moreover, recent studies revealed that ligand activation of these receptors is associated with improved insulin sensitivity and elevated HDL levels thus demonstrating promising potential for targeting PPAR delta in the treatment of obesity, dyslipidemias and type 2 diabetes [11].

Clinical studies of PPAR ligands

Fibric acid derivatives (fibrates) are PPAR alpha ligands. Fibrates have been used in clinical practice for more than four decades as a class of agents known to decrease triglyceride levels while substantially increasing HDL-cholesterol levels, with a limited but significant additional lowering effect on low density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol levels [5]. In addition to their favorable effects on lipid profiles, evidence is mounting that benefits may also stem from the anti-inflammatory and antiatherosclerotic properties of these drugs [12, 13]. Although fibrate trials have reported cardiovascular risk reduction in patients with dyslipidemia, it is evident that the favorable alterations in plasma lipids can only partially explain the reduction in cardiovascular events in these studies. This is particularly evident for high-risk individuals, such as diabetics or patients with insulin resistance who may have more pronounced cardiovascular benefits [5, 12–15].

Glitazones are synthetic PPAR gamma ligands with well recognized effects on glucose and lipid metabolism. The clinical use of these PPARgamma agonists in type 2 diabetic patients leads to an improved glycemic control and an inhanced insulin sensitivity, and – at least in animal models – to a protective effect on pancreatic beta-cell function. Glitazones may also have cardiovascular benefits. Animal models of atherosclerosis have shown that these drugs reduce the extent of atherosclerotic lesions and inhibit macrophage accumulation. Clinical studies have also shown that these drugs improve the lipid profile of patients at risk of developing atherosclerosis and reduce circulating levels of inflammatory markers [16–18]. However, they can produce adverse effects, generally mild or moderate, but some of them (mainly peripheral edema and weight gain) may lead to treatment cessation.

Currently, clinical studies regarding PPAR delta ligands are lacking. Given the results obtained with animal models, PPAR delta agonists may have therapeutic usefulness in metabolic syndrome by increasing fatty acid consumption in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue [19]. Probably, weight reduction could be expected as well.

Dual and pan-PPAR co-agonism

Combined treatments with PPAR gamma and alpha agonists may potentially improve insulin resistance and alleviate atherogenic dyslipidemia, whereas PPAR delta properties may prevent the development of overweight which typically accompanies "pure" PPAR gamma ligands like glitazones. With extended use, it is hoped that these effects will reduce the risk of long-term cardiovascular complications. PPAR alpha and gamma stimulation play complementary roles in the prevention of atherosclerosis. Cholesterol accumulation in macrophages located in the endothelium is a crucial step in the formation of atherosclerosis. PPAR gamma activation is necessary for the efflux of cholesterol from macrophage foam cells. Cholesterol taken up by HDL particles containing apolipoportein A-1 is transported to the liver to be disposed of as bile acids [3, 15, 17]. PPAR alpha agonists, on the other hand, speed up the transfer of cholesterol from macrophages to particles containing apolipoportein A-1 [3, 16, 20].

Thus, compounds with dual PPAR alpha/PPAR gamma activity appear well-suited for the treatment of diabetic patients with the additional risk factor of dyslipidemia. The finding that PPAR agonists play a role in regulating other processes, such as inflammation, vascular function, and vascular remodeling, has highlighted further potential indications for these agents [16, 17]. So far, therefore, a relatively high number of dual PPAR alpha and PPAR gamma agonists have been described [3, 21–25]. The new generation of dual-action PPARs – the glitazars which target PPAR-gamma and PPAR – alpha (muraglitazar and tesaglitazar) are on deck in late-stage clinical trials and may be effective in reducing cardiovascular risk, but their long-term clinical effects are still unknown. A number of glitazars have problems in late stage clinical trials because of serious side-effects (including ragaglitazar and farglitazar).

The bezafibrate lessons: feasibility of dual and pan-PPAR co-agonism in a clinical setting

The old and well known lipid-lowering fibric acid derivative bezafibrate is the first clinically tested pan – (alpha, beta/delta, gamma) PPAR activator [26–33]. It is a sole pan PPAR activator with more than a quarter of a century of a therapeutic experience with a good safety profile. Therefore, bezafibrate could be considered (indeed, as a "post hoc" understanding) as an "archetype" of a clinically tested pan-PPAR ligand. In patients with relevant metabolic abnormalities it is expected to improve both insulin sensitivity and the blood lipid profile and probably reduce the risk of long-term cardiovascular complications. In addition, we can expect prevention of overweight development due to its PPAR-beta/delta properties.

So, which are the data regarding bezafibrate administration? In a large trial in 1568 men with lower extremity arterial disease, bezafibrate reduced the severity of intermittent claudication for up to three years [34]. In general, the incidence of coronary heart disease in patients on bezafibrate has tended to be lower, but this tendency did not reach statistical significance. However, bezafibrate had significantly reduced the incidence of non-fatal coronary events, particularly in those aged <65 years at entry, in whom all coronary events may also be reduced [34]. In two other independent studies bezafibrate decreased the rate of progression of coronary atherosclerosis and decreased coronary events rate [35, 36]. In the the Bezafibrate Infarction Prevention (BIP) study an overall trend of a 9.4% reduction of the incidence of primary end point (fatal or non-fatal myocardial infarction or sudden death) was observed. The reduction in the primary end point in 459 patients with high baseline triglycerides (200 mg/dL or more) was significant [37].

Our new data demonstrate that bezafibrate can significantly reduce the incidence of myocardial infarction (MI) in patients with metabolic syndrome [38]. The decrease in MI incidence among patients on bezafibrate was reflected in a trend to a late risk reduction of cardiac mortality during a long-term follow-up period. This tendency was strengthened in patients with augmented features (at least 4 risk factors for metabolic syndrome) of metabolic syndrome (56% reduction of cardiac mortality during 8-year follow-up). It is interesting that in patients without metabolic syndrome this favorable effect was not presented: There was no significant difference in the cardiovascular end-points between bezafibrate and placebo groups.

Previous observations have shown beneficial effects of bezafibrate on glucose and insulin metabolism [39–41]. Recently, we have shown thata pharmacological intervention with bezafibrate decreased the incidence and delayed the onset of type 2 diabetes in patients with impaired fasting glucose levels, and in obese patients over a long-term follow-up period [42, 43]. In the BIP study the rates of adverse events were similar in both study groups [37]. Thus, bezafibrate treatment was safe in addition to being effective in diabetes prevention. Moreover, there was no significant change in mean body mass index values in either the bezafibrate or the placebo group during the follow-up [38, 42, 43].

Therefore, the pan – (alpha, beta, gamma) PPAR activator bezafibrate leads to a considerable raising of HDL cholesterol and a reduction of triglycerides, improves insulin sensitivity and reduces blood glucose level, significantly lowering the incidence of cardiovascular events and new diabetes in patients with features of metabolic syndrome over a long-term follow-up period. We conclude that clinical evidences obtained from bezafibrate-based studies strongly support the concept of a pan-PPAR therapeutic approach to conditions which comprise the metabolic syndrome. However, from a biochemical point of view, bezafibrate is PPAR ligand with a relatively low potency. We believe that more powerful compounds with pan-PPAR activity and proven long-term safety should be highly effective in a clinical setting of patients with coexisting relevant lipid and glucose metabolism disorders.

Abbreviations

- BIP:

-

Bezafibrate Infarction Prevention

- HDL:

-

high density lipoprotein

- LDL:

-

low density lipoprotein

- MI:

-

myocardial infarction

- PPAR:

-

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- RXR:

-

retinoic acid receptor

References

Vamecq J, Latruffe N: Medical significance of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Lancet. 1999, 354: 141-148. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10364-1.

Tenenbaum A, Fisman EZ, Motro M: Metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus: focus on peroxisome proliferator activated receptors (PPAR). Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2003, 2: 4-10.1186/1475-2840-2-4.

Berger JP, Akiyama TE, Meinke PT: PPARs: Therapeutic targets for metabolic disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005, 26: 244-251. 10.1016/j.tips.2005.03.003.

Kota BP, Huang TH, Roufogalis BD: An overview on biological mechanisms of PPARs. Pharmacol Res. 2005, 51: 85-94. 10.1016/j.phrs.2004.07.012.

Fruchart JC, Staels B, Duriez P: The role of fibric acids in atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2001, 3: 83-92.

Desvergne B, Michalik L, Wahli W: Be fit or be sick: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors are down the road. Mol Endocrinol. 2004, 18: 1321-1332. 10.1210/me.2004-0088.

Argmann CA, Cock TA, Auwerx J: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma: the more the merrier?. Eur J Clin Invest. 2005, 35: 82-92. 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2005.01456.x.

Auwerx J: PPARgamma, the ultimate thrifty gene. Diabetologia. 1999, 42: 1033-1049. 10.1007/s001250051268.

Lazar MA: PPAR gamma, 10 years later. Biochimie. 2005, 87: 9-13. 10.1016/j.biochi.2004.10.021.

Fredenrich A, Grimaldi PA: PPAR delta: an uncompletely known nuclear receptor. Diabetes Metab. 2005, 31: 23-27.

Burdick AD, Kim DJ, Peraza MA, Gonzalez FJ, Peters JM: The role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-beta/delta in epithelial cell growth and differentiation. Cell Signal. 2005, Aug 15.

Staels B, Fruchart JC: Therapeutic roles of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonists. Diabetes. 2005, 54: 2460-2470.

Israelian-Konaraki Z, Reaven PD: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha and atherosclerosis: from basic mechanisms to clinical implications. Cardiology. 2005, 103: 1-9. 10.1159/000081845.

Forcheron F, Cachefo A, Thevenon S, Pinteur C, Beylot M: Mechanisms of the triglyceride- and cholesterol-lowering effect of fenofibrate in hyperlipidemic type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes. 2002, 51: 3486-3491.

Chinetti G, Lestavel S, Fruchart JC, Clavey V, Staels B: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha reduces cholesterol esterification in macrophages. Circ Res. 2003, 92: 212-217. 10.1161/01.RES.0000053386.46813.E9.

Despres JP, Lemieux I, Robins SJ: Role of fibric acid derivatives in the management of risk factors for coronary heart disease. Drugs. 2004, 64: 2177-2198.

Giannini S, Serio M, Galli A: Pleiotropic effects of thiazolidinediones: taking a look beyond antidiabetic activity. J Endocrinol Invest. 2004, 27: 982-991.

Staels B: PPARgamma and atherosclerosis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005, 21 (Suppl 1): S13-20. 10.1185/030079905X36440.

Luquet S, Gaudel C, Holst D, Lopez-Soriano J, Jehl-Pietri C, Fredenrich A, Grimaldi PA: Roles of PPAR delta in lipid absorption and metabolism: a new target for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005, 1740: 313-317.

Ruan XZ, Moorhead JF, Fernando R, Wheeler DC, Powis SH, Varghese Z: PPAR agonists protect mesangial cells from interleukin 1beta-induced intracellular lipid accumulation by activating the ABCA1 cholesterol efflux pathway. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003, 14: 593-600. 10.1097/01.ASN.0000050414.52908.DA.

Goldfarb B: PPAR benefits beyond glucose control. Cardiovascular effects may be even greater with next generation. DOC News. 2005, 2: 14.

Bays H, Stein EA: Pharmacotherapy for dyslipidaemia – current therapies and future agents. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2003, 4: 1901-1938.

Bailey CJ: New pharmacologic agents for diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2001, 1: 119-126.

Pegorier JP: [PPAR receptors and insulin sensitivity: new agonists in development]. Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 2005, 66: 1S10-17.

Darves B: Muraglitazar may help lower glucose and cholesterol levels in type 2 diabetes. Medscape Medical News, ADA 65th Annual Scientific Sessions: Abstracts 967, 14-OR. 2005, [http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/506546]

Peters JM, Aoyama T, Burns AM, Gonzalez FJ: Bezafibrate is a dual ligand for PPARalpha and PPARbeta: studies using null mice. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003, 1632: 80-89.

Cabrero A, Alegret M, Sanchez RM, Adzet T, Laguna JC, Vazquez M: Bezafibrate reduces mRNA levels of adipocyte markers and increases fatty acid oxidation in primary culture of adipocytes. Diabetes . 2001, 50: 1883-1890.

Poirier H, Niot I, Monnot MC, Braissant O, Meunier-Durmort C, Costet P, Pineau T, Wahli W, Willson TM, Besnard P: Differential involvement of peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptors alpha and delta in fibrate and fatty-acid-mediated inductions of the gene encoding liver fatty-acid-binding protein in the liver and the small intestine. Biochem J. 2001, 355: 481-488. 10.1042/0264-6021:3550481.

Vazquez M, Roglans N, Cabrero A, Rodriguez C, Adzet T, Alegret M, Sanchez RM, Laguna JC: Bezafibrate induces acyl-CoA oxidase mRNA levels and fatty acid peroxisomal beta-oxidation in rat white adipose tissue. Mol Cell Biochem. 2001, 216: 71-78. 10.1023/A:1011060615234.

Krey G, Braissant O, L'Horset F, Kalkhoven E, Perroud M, Parker MG, Wahli W: Fatty acids, eicosanoids, and hypolipidemic agents identified as ligands of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors by coactivator-dependent receptor ligand assay. Mol Endocrinol. 1997, 11: 779-791. 10.1210/me.11.6.779.

Moya-Camarena SY, Van den Heuvel JP, Belury MA: Conjugated linoleic acid activates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha and beta subtypes but does not induce hepatic peroxisome proliferation in Sprague-Dawley rats. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999, 1436: 331-342.

Willson TM, Brown PJ, Sternbach DD, Henke BR: The PPARs: from orphan receptors to drug discovery. J Med Chem. 2000, 43: 527-550. 10.1021/jm990554g.

Berger J, Moller DE: The mechanisms of action of PPARs. Annu Rev Med. 2002, 53: 409-435. 10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.104018.

Meade T, Zuhrie R, Cook C, Cooper J: Bezafibrate in men with lower extremity arterial disease: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2002, 325: 1139-10.1136/bmj.325.7373.1139.

Ericsson CG, Nilsson J, Grip L, Svane B, Hamsten A: Effect of bezafibrate treatment over five years on coronary plaques causing 20% to 50% diameter narrowing (The Bezafibrate Coronary Atherosclerosis Intervention Trial [BECAIT]). Am J Cardiol. 1997, 8: 1125-1129. 10.1016/S0002-9149(97)00626-7.

Elkeles RS, Diamond JR, Poulter C, Dhanjil S, Nicolaides AN, Mahmood S, Richmond W, Mather H, Sharp P, Feher MD: Cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of bezafibrate: the St. Mary's, Ealing, Northwick Park Diabetes Cardiovascular Disease Prevention (SENDCAP) Study. Diabetes Care. 1998, 21: 641-648.

Secondary prevention by raising HDL cholesterol and reducing triglycerides in patients with coronary artery disease: the Bezafibrate Infarction Prevention (BIP) study. Circulation. 2000, 102: 21-27.

Tenenbaum A, Motro M, Fisman EZ, Tanne D, Boyko V, Behar S: Bezafibrate for the secondary prevention of myocardial infarction in patients with metabolic syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2005, 165: 1154-1160. 10.1001/archinte.165.10.1154.

Taniguchi A, Fukushima M, Sakai M, Tokuyama K, Nagata I, Fukunaga A, Kishimoto H, Doi K, Yamashita Y, Matsuura T, Kitatani N, Okumura T, Nagasaka S, Nakaishi S, Nakai Y: Effects of bezafibrate on insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion in non-obese Japanese type 2 diabetic patients. Metabolism. 2001, 50: 477-480. 10.1053/meta.2001.21028.

Jonkers IJ, Mohrschladt MF, Westendorp RG, van der Laarse A, Smelt AH: Severe hypertriglyceridemia with insulin resistance is associated with systemic inflammation: reversal with bezafibrate therapy in a randomized controlled trial. Am J Med. 2002, 112: 275-280. 10.1016/S0002-9343(01)01123-8.

Kim JI, Tsujino T, Fujioka Y, Saito K, Yokoyama M: Bezafibrate improves hypertension and insulin sensitivity in humans. Hypertens Res. 2003, 26: 307-313. 10.1291/hypres.26.307.

Tenenbaum A, Motro M, Fisman EZ, Schwammenthal E, Adler Y, Goldenberg I, Leor J, Boyko V, Mandelzweig L, Behar S: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors ligand bezafibrate for prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2004, 109: 2197-2202. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000126824.12785.B6.

Tenenbaum A, Motro M, Fisman EZ, Adler Y, Shemesh J, Tanne D, Leor J, Boyko V, Schwammenthal E, Behar S: Effect of bezafibrate on incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus in obese patients. Eur Heart J. 2005, 26: 2032-2038.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the Cardiovascular Diabetology Research Foundation (RA 58-040-684-1), Holon, Israel, and the Research Authority of Tel-Aviv University (Dr. Ziternick and Haia Silva Ziternick Fund, grants 01250238 and 01250239).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

All authors have equally contributed in the conception and drafting of the manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Tenenbaum, A., Motro, M. & Fisman, E.Z. Dual and pan-peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR) co-agonism: the bezafibrate lessons. Cardiovasc Diabetol 4, 14 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2840-4-14

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2840-4-14