Abstract

Background

Mechanisms involved in metabolic syndrome (MetS) development include insulin resistance, weight regulation, inflammation and lipid metabolism. Aim of this study is to investigate the association of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) involved in these mechanisms with MetS.

Methods

In a random sample of the EPIC-NL study (n = 1886), 38 SNPs associated with waist circumference, insulin resistance, triglycerides, HDL cholesterol and inflammation in genome wide association studies (GWAS) were selected from the 50K IBC array and one additional SNP was measured with KASPar chemistry. The five groups of SNPs, each belonging to one of the metabolic endpoints mentioned above, were associated with MetS and MetS-score using Goeman’s global test. For groups of SNPs significantly associated with the presence of MetS or MetS-score, further analyses were conducted.

Results

The group of waist circumference SNPs was associated with waist circumference (P=0.03) and presence of MetS (P=0.03). Furthermore, the group of SNPs related to insulin resistance was associated with MetS score (P<0.01), HDL cholesterol (P<0.01), triglycerides (P<0.01) and HbA1C (P=0.04). Subsequent analyses showed that MC4R rs17782312, involved in weight regulation, and IRS1 rs2943634, related to insulin resistance were associated with MetS (OR 1.16, 95%CI 1.02-1.32 and OR 0.88, 95% CI 0.79; 0.97, respectively). The groups of inflammation and lipid SNPs were neither associated with presence of MetS nor with MetS score.

Conclusions

In this study we found support for the hypothesis that weight regulation and insulin metabolism are involved in MetS development. MC4R rs17782312 and IRS1 rs2943634 may explain part of the genetic variation in MetS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a common multi-component condition consisting of abdominal obesity, dyslipidaemia, hypertension and hyperglycaemia. It is associated with an increased risk of CVD (cardiovascular diseases) and T2D(type 2 diabetes) [1]. A central question in understanding MetS is why its underlying traits cluster together.

Several mechanisms, including insulin resistance [1], abdominal obesity [1], and inflammation [2, 3] have been proposed to underlie the clustering of MetS features. However, the etiology of MetS has not been unravelled completely yet. Genetic association studies may help to better understand MetS etiology.

A systematic review of genetic association studies on MetS showed that until now most SNPs for which an association with MetS has been found were involved in lipid metabolism [4]. In a recent genome-wide association study (GWAS) even all single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with MetS were involved in lipid metabolism [5]. If effect sizes of SNPs involved in weight regulation and insulin resistance, pathways for which strong pathophysiological evidence exists [1], are small, these SNPs would not have been detected in GWAS, which have a low power due to adjustment for the large number of associations tested.

The SNPs for which an association with MetS has been established explain only a small part of the genetic variation in MetS [4–6]. Therefore, many more genetic variants remain to be discovered. SNPs associated with insulin resistance, abdominal obesity, inflammation and lipid levels in GWAS are likely candidates for an association with MetS itself. For several of these SNPs, however, an association with MetS has not been investigated with a candidate gene approach.

A common feature of genetic association studies is that the power to detect associations is low, because of small effect sizes and the small alpha caused by adjustment for multiple testing. A way to account for this problem is to increase the effect size and reduce the number of tests, by studying the joint effect of a group of SNPs [7]. To the best of our knowledge such an approach has not been undertaken in relation to MetS.

Therefore the aim of this study is to get more insight in the etiology of MetS, by studying associations between MetS and groups of SNPs that were found to be related to insulin resistance, abdominal obesity, inflammation or lipid levels in GWAS. For those groups of SNPs associated with MetS, we also study the association with the individual SNPs in this group.

Methods

EPIC-NL: Study design

In the EPIC-NL cohort the two Dutch contributions to the European Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) project are combined: the Prospect-EPIC and the MORGEN-EPIC (Monitoring Project on Risk Factors for Chronic Diseases) cohorts. Both cohorts were initiated in 1993.The study design of the combined cohort is described in detail elsewhere [8]. In brief, Prospect is a prospective cohort study among 17 357 women aged 49–70 who participated in a breast cancer screening program between 1993 and 1997. The MORGEN-project consists of 22 654 men and women aged 20–59 years recruited from three Dutch towns (Amsterdam, Doetinchem, and Maastricht). From 1993 to 1997, each year a new random sample of approximately 5000 individuals were examined.

Laboratory and genetic analyses were performed in a 6.5% random sample of the EPIC-NL study, in all incident T2D cases and in all incident CVD cases. In our study we only used the random sample. After exclusion of participants with missing blood samples (n = 157), missing values for haemoglobin A1c (HbA1C), waist circumference, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, triglycerides or C-reactive protein (CRP) (n = 128), or with missing SNP data (n=433) the study population consisted of 1886 participants. All participants signed informed consent before study inclusion. Both studies complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Prospect-EPIC study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University Medical Center Utrecht and the MORGEN project was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of TNO, The Netherlands.

Baseline measurements

At baseline, a physical examination was performed and non-fasting blood samples were drawn. During the physical examination, systolic and diastolic blood pressure measurements were performed twice in the supine position on the right arm using a BosoOscillomat (Bosch & Son, Jungingen, Germany) (Prospect) or on the left arm using a random zero sphygmomanometer (MORGEN). The mean of both measurements was taken. Waist circumference and height were measured to the nearest 0.5 cm. Body weight was measured with light indoor clothing without shoes on, to the nearest 100 gr.

Biomarker measurements

HbA1c was measured with a homogeneous assay with enzymatic endpoint in erythrocytes. Trigycerides were measured in EDTA plasma using enzymatic methods, whereas hsCRP was measured with a turbidimetric method [8]. MetS was defined according to an adapted version of the AHA/NHLBI MetS definition as having at least 3 of the following 5 MetS features [9]: abdominal obesity (waist circumference ♂≥102 cm; ♀≥ 88 cm); low HDL cholesterol (♂ <1.0; ♀<1.3 mmol/L); hypertriglyceridemia ( ≥1.7 mmol/L); hypertension ( ≥130/85 mm Hg or use of hypertensive medicication); hyperglycemia (HbA1C ≥5.7% or glucose lowering medication) [10, 11]. MetS-score was calculated by summing the number of MetS features present in each participant.

Genotyping

Genomic DNA was extracted in different batches using standard methods, such as salting out, QIAamp® Blood Kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA, USA). The participants were genotyped using a gene-centric 50K iSelect chip array, further referred to as IBC array [12]. The design and coverage of the IBC array compared to conventional genome-wide genotyping arrays has been described in detail elsewhere [12]. Additionally, the MC4R rs17782313SNP was genotyped in 853 women of the random sample with the KASPar chemistry, an allele-specific PCR SNP genotyping that uses FRET quencher cassette oligos [13]. For this SNP genomic DNA was extracted with an in-house developed extraction method at Kbiosciences (Hoddesdon Herts, UK).

From the available SNPs, we selected those significantly associated (P≤1.0*10-5) with waist circumference, inflammatory markers, triglycerides or HDL cholesterol or homeostasis model assessment insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) in published GWAS until 01-01-2011. As only a few GWAS on HOMA-IR are conducted, we additionally included SNPs both associated with a glucose related traits in GWAS (P≤1.0*10-5) and with HOMA-IR (P≤0.05). Highly correlated proxy SNPs were included in case the original SNP from the GWAS was not available on the IBC array (r2CEU 1000 Genome Pilot 1 ≥ 0.80). If SNPs were only found in one GWAS, without a replication sample, they were excluded. In total we included 39 SNPs: 2 SNPs associated with waist circumference, 5 SNPs associated with insulin resistance, 6 SNPs associated with inflammation, 16 SNPs associated with triglycerides and 16 SNPs associated with HDL cholesterol (Table 1). Sixteen SNPs which were associated in GWAS with waist circumference, inflammatory biomarkers and lipid levels were not on the IBC CVD array (Appendix I).

Statistics

Distributions of genotypes were tested for deviation from hardy-weinberg equilibrium (HWE) by chi-square analyses. Triglycerides and hsCRP were log-transformed to improve normality. Participants on blood pressure medication were excluded from the analyses on blood pressure, participants on glucose lowering medication from the analysis on HbA1C, and participants with acute inflammation (hsCRP > 10 mmol/L) from the analyses on hsCRP.

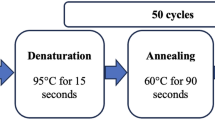

SNPs were divided into 5 groups (Table 1) according to the known associations in GWAS. These groups of SNPs were associated with the corresponding phenotype using the linear regression model of Goeman’s global test [7]. Subsequently, for each group of SNPs the association with MetS was analysed using the log-linear model of Goeman’s global test, and the association with MetS-score using the linear regression model of Goeman’s global test (see Figure 1: data-analyses scheme). If one of these associations was statistically significant, we conducted additional data-analyses. First, to see whether the association with the group of SNPs was mediated by the corresponding phenotype from GWAS, we adjusted the association between MetS and the group of SNPs for this phenotype. Second, we tested if the group of SNPs was also associated with the individual MetS features or hsCRP using the linear regression model of Goeman’s global test. Third, we analysed the association of the individual SNPs in this group with MetS using log-linear models and with MetS-score using linear regression. For the individual SNPs which were significantly associated with MetS or MetS-score, we analysed associations with the individual MetS features and hsCRP using linear regression. We only conducted analyses with individual SNPs, for those SNPs which were on the group level associated with MetS or MetS-score. Consequently, only a few associations with individual SNPs were analyses. Therefore, adjustment for multiple testing is not appropriate.

All analyses were adjusted for age, sex and cohort. Significance was defined as a 2-sided P-value <0.05. The global test was calculated in R version 2.12.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing; http://www.r-project.org). The analyses for individual SNPs were performed with SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, INC., Cary, North Carolina).

Results

All SNPs were in HWE (P>0.05). Minor allele frequency of the SNPs ranged from 0.04-0.47 (Table 1). The random sample of EPIC-NL consisted of 465 men and 1421 women (Table 2). The mean age was 50.1 (SD 11.7) and 30.3% of all participants had MetS.

The group of abdominal obesity SNPs was significantly associated with waist circumference (P=0.01), the group of insulin resistance SNP with HbA1C (P=0.04) and the group of inflammation SNPs with hsCRP (P=7.3*10-6). In contrast, the group of triglyceride SNPs was not significantly associated with serum triglycerides (p=0.08) and the group of HDL cholesterol SNPs not with HDL cholesterol (P=0.32).

P-values for the association of all groups of SNPs with MetS or MetS-score are shown in Table 3. The group of SNPs known for their association with insulin resistance, was borderline significantly associated with MetS (P=0.06) and statistical significantly associated with MetS-score (P=0.003). This group of SNPs was also significantly associated with HbA1C, triglycerides and HDL cholesterol (Table 3). The associations of this group of SNPs with MetS-score and MetS features weakened slightly after adjustment for HbA1C (Table 3). Of the five insulin resistance SNPs included in the group IRS1 rs2943634 was the only SNP individually associated with MetS or MetS-score (Table 4). These associations remained after adjustment for HbA1C (data not shown). IRS1 rs2943634 was also associated with HbA1C (per allele difference −0.034, 95% CI −0.070; 0.002), triglycerides (per allele difference −0.051, 95% CI −0.085; -0.017) and HDL cholesterol (per allele difference 0.029, 95% CI 0.008; 0.052).

The group of SNPs known for their association with waist circumference, was statistical significantly associated with MetS (P=0.03) and tended to be associated with MetS-score (P=0.08). The association with MetS and the suggested association with MetS-score disappeared after adjustment for waist circumference (Table 3). Furthermore, no association was found with any individual MetS feature except for waist circumference (Table 3). Of the two abdominal obesity SNPs only MC4R rs17782313 was individually associated with MetS (Table 4). This association remained after adjustment for waist circumference.

MC4R rs17782313 was not associated with any individual MetS feature, including waist circumference itself (data not shown). The groups of SNPs linked in GWAS with inflammation, triglycerides or HDL cholesterol were neither associated with MetS nor with MetS-score (all P-values ≥ 0.15). Therefore no further data-analyses were done for these groups of SNPs.

Discussion

In this population based study of 1886 participants, we studied the relation between MetS and groups of SNPs associated in GWAS with waist circumference, insulin resistance, inflammation, triglycerides or HDL cholesterol. Only the group of waist circumference SNPs and the group of insulin resistance SNPs were associated with MetS or MetS-score.

Waist circumference SNPs

In our study the group of SNPs which were associated with waist circumference in GWAS (MC4R rs17782313 and FTO rs1421085) was associated with waist circumference, as well as with MetS. The association with MetS disappeared after adjustment for waist circumference, indicating that the association with MetS is driven by the association with waist circumference. Furthermore, the association with MetS seemed mainly to be driven by MC4R rs17782313. In the KORA study among 7888 adults, an association between MC4R rs2229616 (r2=1 with rs17782313) and MetS was found [30], supporting our findings. Unfortunately, in our study, data on MC4R rs17782313 were available for women only. However, since in the KORA study [30] the association between MC4R rs2229616 and MetS was not dependent on sex, we expect that this did not influence our findings. In our study the association between MC4R rs17782313 and MetS remained after adjustment for waist circumference. Furthermore, we found no association between MC4R rs17782313 and any individual MetS feature, including waist circumference. This suggests that the association between MC4R rs17782313 and MetS, is at least in part, independent of body weight. In both human and animal studies MC4R rs17782313 had an effect on insulin resistance, independent of body weight [31, 32]. Therefore, insulin resistance may explain part of the association between MC4R rs17782313 and MetS. Contrary to a meta-analysis among 12,555 Europeans, in which FTO rs9939609 (r2=1 with rs1421085) was significantly associated with MetS (OR 1.17 ; 95% CI 1.10-1.25) [33], we did not observe an association between FTO rs1421085 and MetS. This discrepancy may be explained by the weak association between FTO rs1421085 and waist circumference in our study. In our study the regression coefficient between FTO rs1421085 and waist circumference was 0.03 per SD, whereas in other studies it ranged from 0.07 per SD to 0.14 per SD [33].

Insulin resistance SNPs

We found an association between insulin resistance SNPs and MetS and MetS-score that remained after adjustment for HbA1c, indicating that this association was not driven by HbA1C. However, since HbA1C is not an optimal marker of insulin resistance (r2 between HOMA-IR – HbA1C ≈0.50 [34]), we can not rule out that insulin resistance mediates this association. Out of the group of five insulin resistance SNPs, IRS1 rs2943634 was the only SNP significantly associated with MetS and MetS score. It was also associated with HbA1C, triglycerides and HDL cholesterol. Accordingly an IRS1 knock-out mouse model displayed a MetS like phenotype with insulin resistance, increased blood pressure, increased triglycerides, decreased HDL cholesterol and decreased LPL activity [35]. Furthermore, in human studies IRS1 rs2943634 has been associate with glucose related [15] and lipid traits [36]. In contrast, in a study among 1126 non-Hispanic whites, 898 non-Hispanic blacks and 906 Mexican Americans, IRS1 rs7578326 (r2 with rs2943634=0.82) was not associated with MetS, neither in the overall population, nor in specific ethnic groups [37]. However, as the number of Caucasian participants and MetS prevalence were lower than in our study, the former study may have been underpowered in Caucasian. Besides IRS1 rs2943634 the group of insulin resistance SNPs consisted of PPARG rs1801282, GCKR rs780094, GCK rs1799884, and IGF1 rs35767. In line with other studies, none of these SNPs were associated with MetS in our data [4, 37, 38]. This may be explained by the relatively weak effect on HOMA-IR of PPARG rs1801282, GCK rs1799884, and IGF1 rs35767 [14, 15] or by pleiotropic effects of PPARG rs1801282 and GCKR rs780094. The 12Pro allele of PPARG rs1801282 has opposite effects on insulin resistance and BMI in Caucasian subjects [39, 40], whereas GCKR rs780094 has opposite effects on insulin resistance and lipid levels [27]. These opposite effects may result in a zero association with MetS, as observed by for example Passaro et al. [40].

Lipid SNPs

We did not observe an association between groups of SNPs known for their association with triglycerides or HDL cholesterol and MetS. On the contrary, in a GWAS [5] and a systematic review of genetic association studies [4], the majority of SNPs associated with MetS was involved in lipid metabolism. The lack of an association with MetS may be a power issue, because the association between lipid SNPs and lipid levels was relatively weak in EPIC-NL. Subgroup analyses revealed that these weak associations were consistent for all lipid SNPs and could not be explained by medication use, sex or a difference between the MORGEN and Prospect study. Furthermore, it is unlikely that the non-fasting state of our samples gives an explanation, as in a GWAS, the association with lipid levels was independent of the fasting state for most SNPs [41].

Inflammation SNPs

We found no significant association between a group of inflammation SNPs and MetS. Accordingly, in a study among 4286 British women, a CRP haplotype was not associated with the individual features of MetS [42]. Furthermore, Rafiq et al. could not detect an association between T2D, an endpoint of MetS and 8 SNPs known to alter circulating levels of inflammatory proteins, which were located in the IL-18, IL1RN, IL6R, MIF, PAII and CRP genes [43]. Overall, this evidence may suggest that genetic variants in inflammatory genes do not play a causal role in MetS development. However, for several reasons it cannot be ruled out that some SNPs in inflammatory pathways are causally related to MetS. First, for some inflammatory proteins SNP-MetS associations have not been investigated yet. Second, as the global test gives a combined result for all SNPs, the global test may be not significant despite the presence of an association between one of the single SNPs and MetS.

In this study we have explored the biomarkers involved in MetS development, by studying SNPs related to these biomarkers. Advantage of this approach is that according to the principles of Mendelian randomization the associations we investigated are neither affected by reverse causality nor by socioeconomic and behavioural confounders [44]. Furthermore, as all participants were Caucasian, it is unlikely that our study results have been affected by population stratification. However, for some SNPs we measured, like IRS1 rs2943634 [45], allele frequencies are very heterogeneous among different populations. Therefore, our results warrant replication in other study populations. Sixteen SNPs which were associated in GWAS with MetS related traits were not on the IBC CVD array. Inclusion of the three waist circumference SNPs, which were not on the array, would probably have increased the possibility to find associations with several MetS features. As the global test of inflammation SNPs on hsCRP was already highly significant (P=7.3*10-6), inclusion of additional SNPs, which were absent on the IBC CVD array, would not have changed our results for the global test, but may have revealed additional individual SNPs. The total number of lipid SNPs in our study was relatively large and relatively few lipid SNPs were missing. Therefore we believe that inclusion of additional lipid SNPs would not have changed our results considerably on the group level. The IBC CVD array covered all insulin resistance SNPs discovered in GWAS. However, up till now for only three SNPs a genome wide association with HOMA-IR has been found and replicated. To increase power we also included those SNPs associated with glucose related traits in GWAS, which were also associated with HOMA-IR (P≤0.05). However, as the association between the group of insulin resistance SNPs and HbA1C was just significant, the power to detect associations with MetS and its features was still low.

In conclusion, we found that SNPs associated with waist circumference or insulin resistance in GWAS were also associated with MetS. These results are in line with the hypotheses that weight regulation and insulin metabolism are causative factors for MetS.

Individual SNPs for which we found an association with MetS were MC4R rs17782312 which is involved in weight regulation and IRS1 rs2943634 which is involved in insulin resistance.

Appendix I

Loci related to waist circumference, insulin resistance, inflammatory biomarkers, triglycerides and HDL cholesterol in genome wide association studies till 01-01-2011 which are not on the IBC CVD array.

Funding

The EPIC-NL study was funded by the “Europe against Cancer” Program of the European Commission (SANCO), the Dutch Ministry of Health, the Dutch Cancer Society, the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMW), and World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF).

Abbreviations

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular diseases

- GWAS:

-

Genome-wide association study

- HbA1C:

-

Haemoglobin A1c

- HDL:

-

High-density lipoprotein

- HWE:

-

Hardy-weinberg equilibrium

- HOMA-IR:

-

Homeostasis model assessment insulin resistance

- hsCRP:

-

High sensitive C-reactive protein

- MetS:

-

Metabolic syndrome

- SNP:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- T2D:

-

Type 2 diabetes.

References

Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ: The metabolic syndrome. Lancet. 2005, 365 (9468): 1415-1428. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66378-7.

Hotamisligil GS: Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006, 444 (7121): 860-867. 10.1038/nature05485.

Sutherland JP, McKinley B, Eckel RH: The metabolic syndrome and inflammation. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2004, 2 (2): 82-104. 10.1089/met.2004.2.82.

Povel CM, Boer JMA, Reiling E, Feskens EJM: Genetic variants and the metabolic syndrome: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2011, 12 (11): 952-967. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00907.x.

Kraja AT, Vaidya D, Pankow JS, Goodarzi MO, Assimes TL, Kullo IJ, Sovio U, Mathias RA, Sun YV, Franceschini N, et al: A Bivariate Genome-Wide Approach to Metabolic Syndrome: STAMPEED Consortium. Diabetes. 2011, 60 (4): 1329-1339. 10.2337/db10-1011.

Bosy-Westphal A, Onur S, Geisler C, Wolf A, Korth O, Pfeufferm M, Schrezenmeir J, Krawczak M, Muller MJ: Common familial influences on clustering of metabolic syndrome traits with central obesity and insulin resistance: the Kiel obesity prevention study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2007, 31 (5): 784-790.

Goeman JJ, van de Geer SA, de Kort F, van Houwelingen HC: A global test for groups of genes: testing association with a clinical outcome. Bioinformatics. 2004, 20 (1): 93-99. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg382.

Beulens JW, Monninkhof EM, Verschuren WM, van der Schouw YT, Smit J, Ocke MC, Jansen EH, van Dieren S, Grobbee DE, Peeters PH, et al: Cohort profile: the EPIC-NL study. Int J Epidemiol. 2010, 39 (5): 1170-1178. 10.1093/ije/dyp217.

Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, Gordon DJ, Krauss RM, Savage PJ, Smith SC, et al: Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome. An American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Executive summary. Cardiol Rev. 2005, 13 (6): 322-327.

American Diabetes Association: Standards of medical care in diabetes–2010. Diabetes. 2010, 33 (Suppl 1): S11-S61.

American Diabetes Association: Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes. 2010, 33 (Suppl 1): S62-S69.

Keating BJ, Tischfield S, Murray SS, Bhangale T, Price TS, Glessner JT, Galver L, Barrett JC, Grant SF, Farlow DN, et al: Concept, design and implementation of a cardiovascular gene-centric 50 k SNP array for large-scale genomic association studies. PLoS One. 2008, 3 (10): e3583-10.1371/journal.pone.0003583.

Bauer F, Elbers CC, Adan RA, Loos RJ, Onland-Moret NC, Grobbee DE, van Vliet-Ostaptchouk JV, Wijmenga C, van der Schouw YT: Obesity genes identified in genome-wide association studies are associated with adiposity measures and potentially with nutrient-specific food preference. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009, 90 (4): 951-959. 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27781.

Dupuis J, Langenberg C, Prokopenko I, Saxena R, Soranzo N, Jackson AU, Wheeler E, Glazer NL, Bouatia-Naji N, Gloyn AL, et al: New genetic loci implicated in fasting glucose homeostasis and their impact on type 2 diabetes risk. Nat. 2010, 42 (2): 105-116. 10.1038/ng.520.

Rung J, Cauchi S, Albrechtsen A, Shen L, Rocheleau G, Cavalcanti-Proenca C, Bacot F, Balkau B, Belisle A, Borch-Johnsen K, et al: Genetic variant near IRS1 is associated with type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. Nat Genet. 2009, 41 (10): 1110-1115. 10.1038/ng.443. Epub 2009 Sep 1116

Lindgren CM, Heid IM, Randall JC, Lamina C, Steinthorsdottir V, Qi L, Speliotes EK, Thorleifsson G, Willer CJ, Herrera BM, et al: Genome-wide association scan meta-analysis identifies three Loci influencing adiposity and fat distribution. PLoS Genet. 2009, 5 (6): e1000508-10.1371/journal.pgen.1000508.

Elliott P, Chambers JC, Zhang W, Clarke R, Hopewell JC, Peden JF, Erdmann J, Braund P, Engert JC, Bennett D, et al: Genetic Loci associated with C-reactive protein levels and risk of coronary heart disease. JAMA. 2009, 302 (1): 37-48. 10.1001/jama.2009.954.

Richards JB, Waterworth D, O’Rahilly S, Hivert MF, Loos RJ, Perry JR, Tanaka T, Timpson NJ, Semple RK, Soranzo N, et al: A genome-wide association study reveals variants in ARL15 that influence adiponectin levels. PLoS Genet. 2009, 5 (12): e1000768-10.1371/journal.pgen.1000768.

He M, Cornelis MC, Kraft P, van Dam RM, Sun Q, Laurie CC, Mirel DB, Chasman DI, Ridker PM, Hunter DJ, et al: Genome-wide association study identifies variants at the IL18-BCO2 locus associated with interleukin-18 levels. Arterioscler. 2010, 30 (4): 885-890. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.199422.

Ridker PM, Pare G, Parker A, Zee RY, Danik JS, Buring JE, Kwiatkowski D, Cook NR, Miletich JP, Chasman DI: Loci related to metabolic-syndrome pathways including LEPR,HNF1A, IL6R, and GCKR associate with plasma C-reactive protein: the Women’s Genome Health Study. Am J Hum Genet. 2008, 82 (5): 1185-1192. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.03.015. Epub 2008 Apr 1124

Waterworth DM, Ricketts SL, Song K, Chen L, Zhao JH, Ripatti S, Aulchenko YS, Zhang W, Yuan X, Lim N, et al: Genetic variants influencing circulating lipid levels and risk of coronary artery disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010, 30 (11): 2264-2276. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.201020.

Sabatti C, Service SK, Hartikainen AL, Pouta A, Ripatti S, Brodsky J, Jones CG, Zaitlen NA, Varilo T, Kaakinen M, et al: Genome-wide association analysis of metabolic traits in a birth cohort from a founder population. Nat Genet. 2009, 41 (1): 35-46. 10.1038/ng.271.

Kathiresan S, Melander O, Guiducci C, Surti A, Burtt NP, Rieder MJ, Cooper GM, Roos C, Voight BF, Havulinna AS, et al: Six new loci associated with blood low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol or triglycerides in humans. Nat Genet. 2008, 40 (2): 189-197. 10.1038/ng.75.

Willer CJ, Sanna S, Jackson AU, Scuteri A, Bonnycastle LL, Clarke R, Heath SC, Timpson NJ, Najjar SS, Stringham HM, et al: Newly identified loci that influence lipid concentrations and risk of coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2008, 40 (2): 161-169. 10.1038/ng.76.

Wallace C, Newhouse SJ, Braund P, Zhang F, Tobin M, Falchi M, Ahmadi K, Dobson RJ, Marcano AC, Hajat C, et al: Genome-wide association study identifies genes for biomarkers of cardiovascular disease: serum urate and dyslipidemia. Am J Hum Genet. 2008, 82 (1): 139-149. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.11.001.

Kathiresan S, Willer CJ, Peloso GM, Demissie S, Musunuru K, Schadt EE, Kaplan L, Bennett D, Li Y, Tanaka T, et al: Common variants at 30 loci contribute to polygenic dyslipidemia. Nat Genet. 2009, 41 (1): 56-65. 10.1038/ng.291.

Aulchenko YS, Ripatti S, Lindqvist I, Boomsma D, Heid IM, Pramstaller PP, Penninx BW, Janssens AC, Wilson JF, Spector T, et al: Loci influencing lipid levels and coronary heart disease risk in 16 European population cohorts. Nat Genet. 2009, 41 (1): 47-55. 10.1038/ng.269.

Ridker PM, Pare G, Parker AN, Zee RY, Miletich JP, Chasman DI: Polymorphism in the CETP gene region, HDL cholesterol, and risk of future myocardial infarction: Genomewide analysis among 18 245 initially healthy women from the Women’s Genome Health Study. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2009, 2 (1): 26-33. 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.108.817304.

Teslovich TM, Musunuru K, Smith AV, Edmondson AC, Stylianou IM, Koseki M, Pirruccello JP, Ripatti S, Chasman DI, Willer CJ, et al: Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Nature. 2010, 466 (7307): 707-713. 10.1038/nature09270.

Heid IM, Vollmert C, Kronenberg F, Huth C, Ankerst DP, Luchner A, Hinney A, Bronner G, Wichmann HE, Illig T, et al: Association of the MC4R V103I polymorphism with the metabolic syndrome: the KORA Study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008, 16 (2): 369-376. 10.1038/oby.2007.21.

Butler AA, Cone RD: The melanocortin receptors: lessons from knockout models. Neuropeptides. 2002, 36 (2–3): 77-84.

Chambers J, Elliott P, Zabaneh D, Zhang W, Li Y, Froguel P, Balding D, Scott J, Kooner JS: Common genetic variation near MC4R is associated with waist circumference and insulin resistance. Nat Genet. 2008, 40 (6): 716-718. 10.1038/ng.156.

Freathy RM, Timpson NJ, Lawlor DA, Pouta A, Ben-Shlomo Y, Ruokonen A, Ebrahim S, Shields B, Zeggini E, Weedon MN, et al: Common variation in the FTO gene alters diabetes-related metabolic traits to the extent expected given its effect on BMI. Diabetes. 2008, 57 (5): 1419-1426. 10.2337/db07-1466.

Borai A, Livingstone C, Abdelaal F, Bawazeer A, Keti V, Ferns G: The relationship between glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) and measures of insulin resistance across a range of glucose tolerance. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2011, 71 (2): 168-172.

Abe H, Yamada N, Kamata K, Kuwaki T, Shimada M, Osuga J, Shionoiri F, Yahagi N, Kadowaki T, Tamemoto H, et al: Hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, and impaired endothelium-dependent vascular relaxation in mice lacking insulin receptor substrate-1. J Clin Invest. 1998, 101 (8): 1784-1788. 10.1172/JCI1594.

Kilpelainen TO, Zillikens MC, Stancakova A, Finucane FM, Ried JS, Langenberg C, Zhang W, Beckmann JS, Luan J, Vandenput L, et al: Genetic variation near IRS1 associates with reduced adiposity and an impaired metabolic profile. Nat Genet. 2011, 43 (8): 753-760. 710.1038/ng.1866.

Vassy JL, Shrader P, Yang Q, Liu T, Yesupriya A, Chang MH, Dowling NF, Ned RM, Dupuis J, Florez JC, et al: Genetic associations with metabolic syndrome and its quantitative traits by race/ethnicity in the United States. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2011, 9 (6): 475-482. 10.1089/met.2011.0021.

Sjogren M, Lyssenko V, Jonsson A, Berglund G, Nilsson P, Groop L, Orho-Melander M: The search for putative unifying genetic factors for components of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetologia. 2008, 51 (12): 2242-2251. 10.1007/s00125-008-1151-4.

Tonjes A, Scholz M, Loeffler M, Stumvoll M: Association of Pro12Ala polymorphism in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma with Pre-diabetic phenotypes: meta-analysis of 57 studies on nondiabetic individuals. Diabetes Care. 2006, 29 (11): 2489-2497. 10.2337/dc06-0513.

Passaro A, Dalla Nora E, Marcello C, Di Vece F, Morieri ML, Sanz JM, Bosi C, Fellin R, Zuliani G: PPARgamma Pro12Ala and ACE ID polymorphisms are associated with BMI and fat distribution, but not metabolic syndrome. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2011, 10: 112-10.1186/1475-2840-10-112.

Chasman DI, Pare G, Mora S, Hopewell JC, Peloso G, Clarke R, Cupples LA, Hamsten A, Kathiresan S, Malarstig A, et al: Forty-three loci associated with plasma lipoprotein size, concentration, and cholesterol content in genome-wide analysis. PLoS Genet. 2009, 5 (11): e1000730-10.1371/journal.pgen.1000730.

Timpson NJ, Lawlor DA, Harbord RM, Gaunt TR, Day IN, Palmer LJ, Hattersley AT, Ebrahim S, Lowe GD, Rumley A, et al: C-reactive protein and its role in metabolic syndrome: mendelian randomisation study. Lancet. 2005, 366 (9501): 1954-1959. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67786-0.

Rafiq S, Melzer D, Weedon MN, Lango H, Saxena R, Scott LJ, Palmer CN, Morris AD, McCarthy MI, Ferrucci L, et al: Gene variants influencing measures of inflammation or predisposing to autoimmune and inflammatory diseases are not associated with the risk of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2008, 51 (12): 2205-2213. 10.1007/s00125-008-1160-3.

Davey Smith G, Ebrahim S: ‘Mendelian randomization’: can genetic epidemiology contribute to understanding environmental determinants of disease?. Int J Epidemiol. 2003, 32 (1): 1-22. 10.1093/ije/dyg070.

Yoshiuchi I: Evidence of selection at insulin receptor substrate-1 gene loci. Acta Diabetol. 2012, 15: 15.

Heard-Costa N, Zillikens MC, Monda KL, Johansson A, Harris TB, Fu M, Haritunians T, Feitosa MF, Aspelund T, Eiriksdottir G, et al: NRXN3 is a novel locus for waist circumference: a genome-wide association study from the CHARGE Consortium. PLoS Genet. 2009, 5 (6): e1000539-10.1371/journal.pgen.1000539.

Dehghan A, Dupuis J, Barbalic M, Bis JC, Eiriksdottir G, Lu C, Pellikka N, Wallaschofski H, Kettunen J, Henneman P, et al: Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies in >80 000 subjects identifies multiple loci for C-reactive protein levels. Circulation. 2011, 123 (7): 731-738. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.948570.

Jee SH, Sull JW, Lee JE, Shin C, Park J, Kimm H, Cho EY, Shin ES, Yun JE, Park JW, et al: Adiponectin concentrations: a genome-wide association study. Am J Hum Genet. 2010, 87 (4): 545-552. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.09.004.

Kooner JS, Chambers JC, Aguilar-Salinas CA, Hinds DA, Hyde CL, Warnes GR, Gomez Perez FJ, Frazer KA, Elliott P, Scott J, et al: Genome-wide scan identifies variation in MLXIPL associated with plasma triglycerides. Nat Genet. 2008, 40 (2): 149-151. 10.1038/ng.2007.61.

Pollin TI, Damcott CM, Shen H, Ott SH, Shelton J, Horenstein RB, Post W, McLenithan JC, Bielak LF, Peyser PA, et al: A null mutation in human APOC3 confers a favorable plasma lipid profile and apparent cardioprotection. Science. 2008, 322 (5908): 1702-1705. 10.1126/science.1161524.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution

CMP analyzed the data, contributed to the discussion and wrote the manuscript. JMAB contributed to the discussion and reviewed the manuscript. NCO contributed to the discussion and reviewed the manuscript. MET contributed to the discussion and reviewed the manuscript. EJMF researched the data, contributed to the discussion and reviewed the manuscript. YTS contributed to the discussion and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Povel, C.M., Boer, J.M., Onland-Moret, N.C. et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) involved in insulin resistance, weight regulation, lipid metabolism and inflammation in relation to metabolic syndrome: an epidemiological study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 11, 133 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2840-11-133

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2840-11-133