Abstract

Background

Improving the quality of health care requires a range of evidence-based activities. Audit and feedback is commonly used as a quality improvement tool in the UK National Health Service [NHS]. We set out to assess whether current guidance and systematic review evidence can sufficiently inform practical decisions about how to use audit and feedback to improve quality of care.

Methods

We selected an important chronic disease encountered in primary care: diabetes mellitus. We identified recommendations from National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidance on conducting audit and generated questions which would be relevant to any attempt to operationalise audit and feedback in a healthcare service setting. We explored the extent to which a systematic review of audit and feedback could provide practical guidance about whether audit and feedback should be used to improve quality of diabetes care and, if so, how audit and feedback could be optimised.

Results

National guidance suggests the importance of securing the right organisational conditions and processes. Review evidence suggests that audit and feedback can be effective in changing healthcare professional practice. However, the available evidence says relatively little about the detail of how to use audit and feedback most efficiently.

Conclusion

Audit and feedback will continue to be an unreliable approach to quality improvement until we learn how and when it works best. Conceptualising audit and feedback within a theoretical framework offers a way forward.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A range of strategies exist to promote the uptake of clinical research findings into the routine care of patients. They seek to change the behaviour of healthcare professionals and thereby improve the quality of patient care (Table 1). For each of these strategies a number of trials of their effectiveness have been drawn together within systematic reviews.[1, 2] By examining interventions in a range of settings and circumstances such reviews aim to produce generalisable messages about the effectiveness or otherwise of these interventions.

All healthcare systems are concerned with improving the quality of care that they deliver as demonstrated by their establishment of structures (such as the UK NHS National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE], the Australian National Institute for Clinical Studies) and high profile reports.[3] Across countries clinical audit (hereafter referred to as audit and feedback) is commonly used to both monitor and improve quality of care. [4, 5]

The strategies in Table 1 vary considerably in their resource requirements and cost effectiveness and any healthcare system will have finite resources to commit to quality improvement activities. Therefore to make the best use of health service resources, interventions to change professional behaviour should be evidence-based, selected on the basis of their known effectiveness and efficiency, and should be directed towards important clinical conditions.

While rising prevalence and changing patterns of service delivery diabetes mellitus increasingly contributes to the primary care workload [6] and there is evidence of fragmented and variable provision of care.[7] This paper explores the utility of current systematic review evidence to support healthcare system decisions about how to provide evidence based audit and feedback to improve the quality of care by considering it in the context of a common chronic condition and setting – diabetes mellitus in primary care. We aimed to find out whether we could operationalise audit and feedback from existing review data.

Methods

Topic selection

The UK NHS has produced a framework and set of measurable criteria by which to judge the quality of care for patients with diabetes mellitus. The National Service Framework (NSF) for Diabetes was launched in 2002.[8] It suggests performance targets for primary care organisations, responsible for the commissioning and provision of health care for defined populations. Some of these targets have been incorporated into the revised contract for UK primary care doctors (GPs) reflecting disease monitoring (e.g. HbA1c measurement) or secondary prevention (e.g. proportion of patients with HbA1c under 7.5%).[9] Therefore, diabetes represents an appropriate condition with which to explore the utility of audit: it is a common condition with important consequences, effective interventions are available, measurable outcomes have been defined, and there is potential for improvement in the quality of care.

How best to conduct audit and feedback?

We informed the study with two definitions of audit and feedback (Table 2). The systematic review [5] offers a narrower definition than the National Institute for Clinical Excellence, Principles for Best Practice in Clinical Audit [4] which offers a broader definition and stresses the importance of integrating audit within an overall quality improvement framework. The latter sets out practical considerations for five stages of the audit and feedback process: preparing for audit, selecting criteria, measuring performance, making improvements, and sustaining improvement (Table 3). Much emphasis is given to creating the right organisational structures and culture for success, as well as taking account of local knowledge, experience and skills. Both are relevant to quality improvement at an organisational as well as individual level. However, neither describes in detail the manner in which audit and feedback should be conducted.

We explored the extent to which a systematic review of audit and feedback could provide practical guidance about whether audit and feedback should be used to improve quality of diabetes care and, if so, how audit and feedback could be optimised. Based upon discussions with those responsible for conducting audit and feedback at a local level as well as our own experiences of doing so, we identified several questions which would be relevant to any attempt to operationalise audit and feedback in a healthcare service setting.

-

Does audit and feedback work for this condition and setting, specifically improving the care of patients with a chronic disease – diabetes mellitus – in primary care?

-

Does it work equally across all dimensions of care – from simple recording of cardiovascular risk factors to more complex areas of care such as glycaemic control? The latter requires a greater number of actions to achieve which include measuring blood glucose levels, reviewing the patient, checking compliance with drug and dietary therapies and checking patients' understanding of the condition.

-

How should it be prepared? Should data be comparative and if so, what should the comparator group be? Should data be anonymised?

-

How intensive should feedback be? Intuitively, providing more and personalised feedback on a recurrent and regular basis should have a greater impact on practice than a one-off report of (say) PCT-level aggregated data. However, it is uncertain whether the extra time and costs of ongoing data collection and preparing more frequent feedback would be matched by additional benefits.

-

How should it be delivered – by post or by a messenger in person? And if by a messenger who should this be? Professionals might be more convinced by a message delivered by a colleague with a recognised interest in diabetes care rather than a non-clinical facilitator.

-

What activities, if any, should accompany feedback? The likely costs and possible benefits of (say) educational meetings or outreach visits need to be weighed up against providing feedback via paper or computerised formats alone.

-

What should be done about the poorest performers detected by the audit? Targeting such practices may help close the gap between the poorest and best performers. Alternatively, spreading effort to improve quality more equally amongst all practices may improve average performance for the whole PCT.

Results

The evidence from the systematic review

We identified a systematic review of audit and feedback that identified and appraised 85 randomised trial.[5] Audit and feedback was used for a wide range of clinical topics and problems. The review conclusions were:

-

audit and feedback can improve professional practice, although the effects are generally small to moderate

-

effectiveness varies substantially among different studies

-

variation may be related to different methods of providing feedback or contextual factors, such as targeted behaviours and professionals

The review identified only five direct (head-to-head) comparisons of different methods of providing feedback (Table 4). One comparison suggested that feedback by a peer was more effective than that by a neutral observer [10]; another that feedback from a peer physician was no more effective than that from a nurse.[11] The other three comparisons found no effects related to recipients (group or individual) or content of feedback. None of these studies reported an economic evaluation.

The review also evaluated 14 direct comparisons of audit and feedback alone compared to audit and feedback combined with other interventions (multifaceted interventions). There was no evidence that multifaceted interventions worked better than audit and feedback alone. A multivariate analysis explored potential causes of heterogeneity in the results (study quality, whether audit and feedback was combined with other interventions, intensity of feedback, complexity of the targeted behaviour, and level of baseline compliance). Only low baseline compliance was associated with greater effect sizes for multifaceted interventions. There was no evidence of larger effects with increasing intensity of feedback.

The evidence for chronic disease management

Fifteen studies relate to chronic disease management (hypertension, diabetes, cholesterol control, depression, asthma and end-stage renal failure). Just over half of comparisons indicated that audit and feedback was more effective than doing nothing (Table 4). Using multifaceted interventions or modifying feedback methods did not enhance effectiveness.

The evidence for diabetes care

Four studies evaluated audit and feedback in diabetes care, three set in primary care. Two comparisons addressed one of our key questions (Does audit and feedback work for this condition and setting?) and showed that audit and feedback, with or without other interventions, was more effective than doing nothing.[12, 13] A UK primary care study.[12] showed that a multifaceted intervention incorporating low intensity audit and feedback moderately improved practice, specifically recording of key variables (e.g. glycaemic control, smoking habit). Audit and feedback also moderately increased US primary care physician compliance with guidelines.[13]

Two studies partially addressed three of our key questions about how to conduct audit and feedback (How intensive should feedback be? What activities, if any, should accompany feedback? How should feedback be delivered?). In US secondary care, there was no difference between continuing feedback against withdrawal of feedback in the accuracy of capillary blood glucose monitoring.[14] An Australian study of GPs found a small benefit of feedback given by a doctor or nurse compared with feedback alone, although it is difficult to judge whether the benefits of this approach outweighed the additional costs.[11] There was no difference in effect size between doctor and nurse feedback in this comparison. There was no relationship between study effect size and feedback intensity, co-intervention use or complexity of targeted behaviour across the four studies.

Discussion

The review evidence was of limited use in informing the operationalisation of evidence based audit and feedback. A number of issues contributed to this – the heterogeneity of the studies in the overall review, the problems of interpreting sub-groups of studies within the larger review, and the lack of direct evidence (particularly from head-to-head comparisons) to answer key questions.

It is unclear how to use the review to extract generalisable lessons about how audit and feedback achieves its effects. For example, individual level feedback could reasonably be assumed to be more personally relevant and persuasive and thus more effective than feedback at a group level; there are no such direct comparisons available. Four out of 10 studies using individual feedback for chronic disease management reported no effect whilst both studies using group feedback reported positive effects. Therefore group feedback might be more effective than individual feedback, possibly by promoting peer pressure, consensus and subsequent action. Unfortunately this must all remain conjecture given the paucity of data to test different hypotheses about the causal mechanisms that make audit and feedback work.

Based upon a limited number of comparisons, audit and feedback appears to work better for diabetes than for other conditions. It is unclear whether this is because there is something intrinsically different about diabetes (or the audit methods used in diabetes) compared to other conditions, or whether this is an unreliable sub-group analysis of four studies selected from the 85 available. It is hard to have confidence in the findings of the diabetes studies in the absence of good, preferably a priori, reasons as to why these studies should be examined separately from others in the review.

Similar pitfalls exist in judging the relative effectiveness of different feedback methods. This is mainly because of the limited number of head-to-head comparisons comparing audit and feedback alone against combined interventions or variations in providing feedback. Across all studies, audit and feedback alone appears similarly effective to multifaceted strategies. However, the lack of difference in effect size could have occurred because multifaceted strategies were used in situations where investigators judged them necessary to overcome greater obstacles to improving care. In the absence of primary studies, the review cannot address some of the key questions such as whether intensive feedback would improve more complex outcomes (gylcaemic control) at an acceptable cost.

Mapped back onto the principles for good clinical audit, the evidence only supports doing audit if there is low baseline compliance (Table 3). This evidence relates to situations where there is low mean baseline compliance across all study physicians rather than relating solely to a selected “low compliance” group. Thus it is of no direct relevance to the key question of whether or not audit and feedback can promote change in poorly performing individuals. However, a baseline audit of multiple aspects of diabetes care would enable targeting of implementation activities at areas of low compliance.

The issues of external validity of randomised controlled trials (and by inference, systematic reviews) have been aired in the context of clinical studies.[15, 16]. However, what we have had to deal with here is more to do with inadequate description of the interventions in the primary studies and an inadequate understanding of the causal mechanisms by which the intervention or its variants might exert their effects. Thus this lack of fundamental understanding accounts for the impossibility of assessing a behaviour change interventions' applicability to a particular service setting. We are a long way from being able to do what is now commonplace with clinical studies in terms of assessing the applicability of a clinical study to an individual patient.[17]

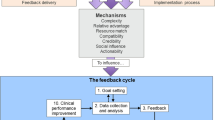

A rational approach to this situation is to develop a conceptual framework within which to describe common elements of settings, individuals, targeted behaviours and interventions [18–20]. This would enable the identification of features that systematically influence the effectiveness of interventions. For example, the effectiveness of audit and feedback may be influenced by factors such as health professionals' motivation to change or perceived peer pressure – generalisable concepts that can be used across different contexts. Behavioural theory can identify potentially modifiable factors underlying professional behaviour in order to identify those processes to target with an intervention. Hence, if perceived peer pressure was predictive of adherence to good practice criteria, feedback incorporating peer comparison might enhance effectiveness. This approach potentially offers a method for more effective selection and development of interventions to improve practice. The longer term possibility is to establish a theoretically grounded basis for selecting or tailoring interventions given specific barriers and circumstances. This would apply to all behaviour change strategies, not just audit and feedback.

Conclusion

Review evidence was of limited use in informing the operationalisation of evidence based audit and feedback. This is mainly because of the heterogeneity of the studies in the overall review, the problems of interpreting sub-groups of studies within the larger review, and the lack of head-to-head comparisons to answer key questions. Audit and feedback will continue to be an unreliable approach to quality improvement until we learn how and when it works best. Conceptualising audit and feedback within a theoretical framework offers a way forward.

Abbreviations

- UK NHS:

-

United Kingdom National Health Service

- NSF:

-

National Service Framework

- GP:

-

General Practitioner

- NICE:

-

National Institute for Clinical Excellence

- HbA1c:

-

Glycosylated haemoglobin

- PCT:

-

Primary Care Trust

References

Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, MacLennan G, Fraser C, Ramsay CR, Vale L, Whitty P, Eccles MP, Matowe L, Shirran L, Wensing M, Dijkstra R, Donaldson C: Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol Assess. 2004, 8 (6): 1-72.

NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination: Getting evidence into practice. Effective Health Care. 1999, University of York

Crossing the quality chasm: the IOM Health Care Quality Initiative. Institute of Medicine. 2001

National Institute for Clinical Excellence: Principles for Best Practice in Clinical Audit. 2002, Abingdon: Radcliffe Medical Press

Jamtvedt G, Young JM, Kristoffersen DT, O'Brien MA, Oxman AD: Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. The Cochrane Library. 2004, Oxford: Update Software, 2

National Service Framework for Diabetes. 2001, London, Department of Health

Audit Commission: Testing Times: A Review of Diabetes Services in England and Wales. 2000, London, Audit Commission

Department of Health: National Service Framework for Diabetes. Delivery Strategy. 2002, London, Department of Health

The NHS Confederation & British Medical Association: 2003, New GMS Contract. London

Hombergh Pvd, Grol R, Hoogen HJMvd, Bosch WJHNvd: Practice visits as a tool in quality improvement: mutual visits and feedback by peers compared with visits and feedback by non-physician observers. Quality in Health Care. 1999, 161-166.

Ward A, Kamien M, Mansfield F, Fatovich B: Educational feedback in management of diabetes in general practice. Education for General Practice. 1996, 7: 142-150.

Feder G, Griffiths C, Highton C, Eldridge S, Spence M, Southgate L: Do clinical guidelines introduced with practice based education improve care of asthmatic and diabetic patients? A randomised controlled trial in general practice. BMJ. 1995, 311: 1473-1478.

Lobach DF: Electronically distributed, computer-generated, individualized feedback enhances the use of a computerized practice guideline. Proc AMIA Annu Fall Symp. 1996, 493-497.

Jones HE, Cleave B, Zinman B, Szalai JP, Nichol HL, Hoffman BR: Efficacy of feedback from quarterly laboratory comparison in maintaining quality of a hospital capillary blood glucose monitoring program. Diabetes Care. 1996, 19: 168-170.

Black N: Why we need observational studies to evaluate the effectiveness of health care. BMJ. 1996, 312: 1215-1218. BMJ 1996; 312:1215-1218.

McKee M, Britton A, Black N, McPherson K, Sanderson C, Bain C: Methods in health services research: Interpreting the evidence: choosing between randomised and non-randomised studies. BMJ. 1999, 319: 312-315.

Dans AL, Dans LF, Guyatt GH, Richardson S: Users' guides to the medical literature: XIV. How to decide on the applicability of clinical trial results to your patient. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1998, 279: 545-549. 10.1001/jama.279.7.545.

Foy R, Eccles M, Grimshaw J: Why does primary care need more implementation research?. Family Practice. 2001, 18: 353-355. 10.1093/fampra/18.4.353.

Walker AE, Grimshaw J, Johnston M, Pitts N, Steen N, Eccles M: PRIME - PRocess modelling in ImpleMEntation research: selecting a theoretical basis for interventions to change clinical practice. BMC Health Serv Res. 2003, 3 (1): 22-10.1186/1472-6963-3-22.

Eccles M, Grimshaw J, Walker A, Johnston M, Pitts N: Changing the behaviour of healthcare professionals: the use of theory in promoting the uptake of research findings. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005, 58: 107-112. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.09.002.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/5/50/prepub

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

GJ and JY undertook the Cochrane Review of audit and feedback. RB co-authored Principles for Best Practice in Clinical Audit. ME suggested the idea for this paper. RF wrote the first draft and is guarantor. All other authors helped draft the manuscript and have approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Foy, R., Eccles, M., Jamtvedt, G. et al. What do we know about how to do audit and feedback? Pitfalls in applying evidence from a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 5, 50 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-5-50

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-5-50