Abstract

Background

Chronic respiratory diseases are a major cause of mortality and morbidity, and represent a high chronic disease burden, which is expected to rise between now and 2020. Care for chronic diseases is increasingly located in community settings for reasons of efficiency and patient preference, though what services should be offered and where is contested. Our aim was to identify the key characteristics of a community-based service for chronic respiratory disease to help inform NHS commissioning decisions.

Methods

We used the Delphi method of consensus development. We derived components from Wagner’s Chronic Care Model (CCM), an evidence-based, multi-dimensional framework for improving chronic illness care. We used the linked Assessment of Chronic Illness Care to derive standards for each component.

We established a purposeful panel of experts to form the Delphi group. This was multidisciplinary and included national and international experts in the field, as well as local health professionals involved in the delivery of respiratory services. Consensus was defined in terms of medians and means. Participants were able to propose new components in round one.

Results

Twenty-one experts were invited to participate, and 18 agreed to take part (85.7% response). Sixteen responded to the first round (88.9%), 14 to the second round (77.8%) and 13 to the third round (72.2%). The panel rated twelve of the original fifteen components of the CCM to be a high priority for community-based respiratory care model, with varying levels of consensus. Where consensus was achieved, there was agreement that the component should be delivered to an advanced standard. Four additional components were identified, all of which would be categorised as part of delivery system design.

Conclusions

This consensus development process confirmed the validity of the CCM as a basis for a community-based respiratory care service and identified a small number of additional components. Our approach has the potential to be applied to service redesign for other chronic conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

There is increasing demand on health services in the UK and other Western countries as a result of ageing populations and the rising prevalence of chronic disease. The current structure of chronic care, which is derived from models of hospital-based acute care, is in need of reform in order to address the specific care needs of long term illness [1, 2]. In response to this need, recent reforms to health and social care in the UK have focused on increasing community-based care [3, 4], including patient self-care through an Expert Patient Programme [5–7], which allows for personalised services and care closer to home.

Chronic respiratory diseases represent a considerable burden on health care services. They contribute to social inequalities in life expectancy, notably through preventable early deaths, as well as to excess winter deaths [8]. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma, and are major causes of morbidity [9, 10]. In the UK, COPD alone accounts for 1.4 million GP consultations per year and 1 in 8 emergency admissions [11], and its prevalence is expected to rise between 2010 and 2020 [8].

There is evidence for the effectiveness of a range of services for COPD when provided in community settings. Pulmonary rehabilitation is a safe and clinically effective intervention, and in less severe cases it can be delivered at home as an alternative to outpatient care [12–16]. It improves exercise capacity, health status and health-related quality of life [12–17]; reduces hospital admissions, time spent in hospital and mortality [13, 17]. Hospital at home is safe, reduces the need for emergency services, and improves quality of life and self-management [18, 19]. It is as effective as inpatient care in terms of mortality and hospital readmissions, though COPD patients may prefer inpatient services to hospital at home [20, 21]. Self-management education improves self-efficacy and self-care, and can reduce hospital admissions [22, 23]. Action plans in particular improve self-management knowledge, such as patients’ ability to recognise and respond appropriately to exacerbations [24]. Group therapy improves health knowledge and quality of life [25]. Multiple intervention programmes reduce hospital admissions and improve quality of life, but require multi-disciplinary input [1, 26]. They are effective in patients with exercise impairment and to reduce hospital admissions and readmission [27, 28].

Existing theoretical models of service provision for chronic disorders include the case management model [29], the complex adaptive chronic care model [30] and psychosocial models [31], though the CCM is the most widely accepted because it is the most comprehensive [32]. However, a systematic review found a limited number of studies that evaluated the effectiveness of the CCM components in COPD management [33]. In the north east of England, primary care commissioners and secondary care providers are collaborating to reduce inefficiencies and to improve quality of care through Quality Improvement Plans [34]. At their request, we sought to identify the key characteristics of a community-based service for chronic respiratory diseases. We defined community-based care to include services that are offered either 1) outside of a family practice or hospital setting, for example in the patient’s home, or 2) on premises from which family practice or hospital services are delivered, but which are outwith what is normally offered.

Methods

Aim

To develop consensus among professionals involved in the care of chronic respiratory diseases on the key characteristics of a community-based respiratory service.

Materials

To develop a model of the ideal service, we used the Delphi technique of consensus development [35]. This involves the generation of group judgements and allows opportunities for participants to revise their responses after formal feedback of group views. We developed a modified Delphi survey based on model elements of Wagner’s Chronic Care Model (CCM). The CCM is an evidence-based multi-dimensional framework for improving chronic illness care, and includes six model elements: organisation of health care; self-management support; delivery system design; decision support; clinical information systems; and community resources and policies [36]. Together these are theorised to lead to productive interactions between the informed, activated patient and the prepared, proactive practice team.

We examined the elements described by both the CCM areas and the linked Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (v3.5) [37, 38]. We identified 15 primary components represented by five of the six model elements (Table 1). We determined that organisation of health care, the sixth model element, was beyond the scope of this exercise since it focussed on chronic care at the level of the health service. The standard to which the components should be delivered was derived from the Assessment of Chronic Illness Care survey [38]. We also offered respondents the opportunity to propose additional components in the course of Round 1.

Sample

We established a purposeful sample by inviting 21 experts [39] to take part, aiming to reach the recommended sample size of around 12 participants and anticipating that response would diminish over consecutive rounds [35]. The panel was multidisciplinary and comprised national and international experts in the field, as well as health professionals involved in the local delivery of respiratory services.

Design

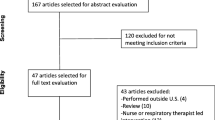

Three rounds were held to build consensus. Surveys were distributed and returned by email. One reminder was sent to non-respondents for each round (Figure 1). Participants who did not respond in round two were nevertheless encouraged and allowed to respond in round three [40].

Analysis

The panel rated the importance of each component on a 9-point scale and the results were grouped by level of priority as either low (1–3 points), moderate (4–6 points) or high (7–9 points) [41].

Consensus was developed by a two step process. First, for any component to reach consensus, the group median and interquartile range had to fall within one level of priority only (either low, moderate or high). Second, the extent to which consensus was met—either general, full or pure—is based on the group mean, standard deviations and the presence of outliers (Table 2).

For the standards to which each component should be delivered, we used a 4-point Likert scale. Four point scales have previously been shown to produce stable findings in Delphi studies [42]. Consensus was reached when the interquartile range lay within 1 unit of the median (on a 4-point Likert scale, with 1 being lowest standard and 4 being the highest).

Ethical issues

No ethical issues were identified in this consensus study, which involved only email contact with health professionals, and ethical approval was not sought.

Results

Respondents

We received expressions of interest to participate from 18 of the 21 experts invited (85.7% response) (Table 3). Sixteen provided responses to the first round (88.9%), 14 to the second round (77.8%) and 13 to the third round (72.2%). Most individuals provided responses to all rounds, although there were 5 people who did not, as we allowed any non-respondents to reply to subsequent rounds [40].

The survey

Over the three rounds, the priority ratings for all components either lowered or remained the same, and there was a narrowing of interquartile ranges. Of the original fifteen components, three were defined as having met ‘general consensus’; five were considered to have reached ‘full consensus’; and four components reached ‘pure consensus’. All those reaching consensus were considered to be a high priority (rating 7–9) for the model. The standard of delivery for each component was also high, in most cases being 1 on a scale of 1 to 4.

Twelve additional components were generated by participants during the first round (Table 4). Consensus was less likely for these. Only four components were considered to be a high priority for the model, with one reaching ‘general consensus’ and three reaching ‘full consensus’. We assigned each new component to a model element.

Final components

There was consensus for twelve of the original fifteen components and four of the additional components (Table 5). In all cases where consensus was met, the component was considered by respondents to be a high priority for the model.

Discussion

Summary of main findings

Using a three-round Delphi consensus method, we have identified the key components of a community-based respiratory service and the standard to which they should be delivered. We used the CCM as our theoretical model and practical guide. Twelve of the fifteen original components of the CCM were considered to be a high priority for community-based respiratory care. Respondents considered that all the agreed components should be delivered to a high standard. We also identified four components additional to the CCM. These may be relevant to chronic care for other diseases as well as for COPD.

Strengths and limitations of the study

A range of disciplines was represented, with local, national and international expertise. Delphi consensus methods do not involve face-to-face discussions between respondents, but do allow for bringing together opinions of people from a range of geographic backgrounds or busy professionals who might not otherwise have the time to meet for a day of discussion [41]. Not all participants responded to all three rounds, which is an expected feature for consensus development techniques. The response rate for each round of the study was, however, greater than the recommended minimum of 70% [43]. There was a low response from nurses, who comprised nearly one quarter of all professionals invited to participate, but represented under one eighth of the final sample. However, given the mix of professionals involved in the delivery of community-based respiratory services in the UK, we assert the sample was representative of the range of professionals in the UK.

Comparison with existing literature

Five of the six model elements from the CCM were represented in the final consensus: self-management support; delivery system design; decision support; clinical information systems; and community resources and policies [36]. This confirms the face validity of the CCM as a model for community-based chronic care. Three of the twelve additional components that arose from round one met with full consensus, and one reached general consensus. All four can be categorised as new components of delivery system design. One (smoking cessation) could be considered as a behaviour change intervention, a second (long term oxygen therapy) is a specific therapeutic intervention, and the third (acute exacerbation) refers to responsiveness of the health system. We have taken the fourth, end-of-life care, to be wider than the CCM component for integrating palliative care into the community. As such, it represents a new and distinct component of delivery system design.

In their systematic review, Dennis et al. [44] found four of the six model elements of the CCM to be effective in disease management. These were continuing professional development for the multidisciplinary team (the decision support element); clear roles of responsibility in a system where self-management is not embedded in primary care (the delivery system design element); and disease registers (the clinical information system element) to facilitate decision support (the decision support element). Little evidence was found for the model elements of community resources and policies, and organisation of health care in primary care. This supports our decision not to include the latter, though we did find a clear need from practitioners for the former. Our findings are in keeping with those of Dennis et al. However, we chose not to address organisation of health care in primary care, which they considered important though lacking in supporting evidence. Furthermore, Adams et al. [33] do not treat this as a separate model element in their analysis of the CCM in COPD.

Implications for practice

The high standard to which most components were recommended to be delivered could pose a challenge to implementation. They may be better viewed as a goal to which service providers could be required to work. Some of the recommended components are not routinely addressed or provided, either in primary or secondary care, and their provision will have resource implications. This approach to developing a model of care for COPD, building upon a well validated conceptual model of care, is applicable to other chronic conditions and consideration should be given to using it to inform the commissioning of new models of chronic care.

Table 6, derived from the Adams et al. [33] systematic review of interventions applying the CCM in COPD care, summarises the four model elements of the CCM that each study applied to their model of community-based care. The review dichotomised findings by either one element or multiple elements. It found significantly lower rates of hospitalizations and emergency/unscheduled visits and a shorter length of stay where multiple main elements were applied. Only half of the 18 community-based studies reviewed included two or more of the model elements of the CCM, and only two included all.

Table 7, also based on Adams et al., summarises the combination of each of the four model elements used to measure improvements in service delivery of COPD. No measures studied used a combination all four model elements, save hospitalisation, making it difficult to draw conclusions as to which combination is optimal. The self-management model element features in most studies that show significant results for a measure of improvement, while the clinical information system model element is rarely used. Dyspnoea, hospitalisation and length of stay seem to require use of multiple model elements. Knowledge may be improved by self-management alone. Mortality does not appear to be improved by any combination, and performance and lung function are understudied in community-based settings.

Conclusions

In this development of a model for community-based respiratory services, consensus was reached on the inclusion of a large proportion of components derived from a well-accepted theoretical model (the CCM). We generated a small number of additional components and these may have wider relevance in chronic care.

This approach to developing consensus has the potential to be applied to service redesign for other chronic conditions. It is likely to be most relevant where a range of professionals provide care for the condition in question and where their experience and the setting for that care is not highly compartmentalised. Examples of amenable conditions could include rheumatological disorders and diabetes.

The number of components that were agreed to be necessary to community respiratory care, and the high standard to which they should be delivered, may pose a challenge to implementation. In the UK, for example, they may need to be seen as an aspiration to which commissioners would work within the context of current resource limitations.

Authors’ information

EH is a researcher for and GR is director of the Evaluation, Research and Development Unit, which provides independent health services research in primary care.

Abbreviations

- CCM:

-

Chronic care model

- NHS:

-

National health service

- PCT:

-

Primary care trust.

References

Lemmens KMM, Nieboer AP, Huijsman R: A systematic review of integrated use of disease-management interventions in asthma and COPD. Respir Med. 2009, 103 (5): 670-691. 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.11.017.

McColl MA, Shortt S, Godwin M, Smith K, Rowe K, O'Brien P, Donnelly C: Models for Integrating Rehabilitation and Primary Care: A Scoping Study. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2009, 90 (9): 1523-1531. 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.03.017.

Department of Health: Our health, our care, our say: a new direction for community services. 2006, Crown copyright, London

Department of Health: Supporting people with long term conditions: An NHS and social care model to support local innovation and integration. 2005, Crown Copyright, London

Department of Health: The expert patient: A new approach to chronic disease management for the 21st century. 2001, Crown Copyright, London

Department of Health: Self care support: A practical option. 2005, Crown Copyright, London

Department of Health: The NHS Improvement Plan : Putting people at the heart of public services. 2004, Crown copyright, London

Joint Strategic Needs Assessment: Looking at future health, care and well-being needs. 2009, A local resource for intelligence-led commissioning. Stockton-on-Tees, Borough Council

World Health Organisation: Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010. 2011, WHO, Geneva

World Health Organisation: Global surveillance, prevention and control of chronic respiratory diseases: A comprehensive approach. 2007, WHO, Geneva

Healthcare commission: Clearing the air: A national study on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2006, Commissioning for Healthcare Audit and Inspection, London

Man WDC, Polkey MI, Donaldson N, Gray BJ, Moxham J: Community pulmonary rehabilitation after hospitalisation for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: randomised controlled study. Br Med J. 2004, 329 (7476): 1209-1211. 10.1136/bmj.38258.662720.3A.

Puhan M, Scharplatz M, Troosters T, Walters EH, Steurer J: Pulmonary rehabilitation following exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009, (1).

Lacasse Y, Goldstein R, Lasserson TJ, Martins S: Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006, (4).

Maltais F, Bourbeau J, Shapiro S, Lacasse Y, Perrault H, Baltzan M, Hernandez P, Rouleau M, Julien M, Parenteau S, et al: Effects of Home-Based Pulmonary Rehabilitation in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease A Randomized Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2008, 149 (12): 869.

Wijkstra PJ, Vanaltena R, Kraan J, Otten V, Postma DS, Koeter GH: Quality-of-life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary-disease improves after rehabilitation at home. Eur Resp J. 1994, 7 (2): 269-273. 10.1183/09031936.94.07020269.

Griffiths TL, Burr ML, Campbell IA, Lewis-Jenkins V, Mullins J, Shiels K, Turner-Lawlor PJ, Payne N, Newcombe RG, Lonescu AA, et al: Results at 1 year of outpatient multidisciplinary pulmonary rehabilitation: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000, 355 (9201): 362-368. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)07042-7.

Ram FSF, Wedzicha JA, Wright J, Greenstone M: Hospital at home for patients with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: systematic review of evidence. Br Med J. 2004, 329 (7461): 315-318. 10.1136/bmj.38159.650347.55.

Hernandez C, Casas A, Escarrabill J, Alonso J, Puig-Junoy J, Farrero E, Vilagut G, Collvinent B, Rodriguez-Roisin R, Roca J, et al: Home hospitalisation of exacerbated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Eur Resp J. 2003, 21 (1): 58-67. 10.1183/09031936.03.00015603.

Shepperd S, Harwood D, Jenkinson C, Gray A, Vessey M, Morgan P: Randomised controlled trial comparing hospital at home care with inpatient hospital care. I: three month follow up of health outcomes. Br Med J. 1998, 316 (7147): 1786-10.1136/bmj.316.7147.1786.

Reishtein JL: Review: hospital at home is as effective as inpatient care for mortality and hospital readmissions in patients with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Evidence-based Nursing. 2005, 8 (1): 23-10.1136/ebn.8.1.23.

Effing T, Monninkhof EM, van der Valk P, van der Palen J, van Herwaarden CLA, Partidge MR, Walters EH, Zielhuis GA: Self-management education for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007, (4).

Griffiths C, Motlib J, Azad A, Ramsay J, Eldridge S, Feder G, Khanam R, Munni R, Garrett M, Turner A, et al: Randomised controlled trial of a lay-led self-management programme for Bangladeshi patients with chronic disease. Br J Gen Pract. 2005, 55 (520): 831-837.

Turnock AC, Walters EH, Walters JAE, Wood-Baker R: Action plans for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005, (4).

Woo J, Chan W, Yeung F, Chan WM, Hui E, Lum CM, Or KH, Hui DSC, Lee DTF: A community model of group therapy for the older patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a pilot study. J Eval Clin Pract. 2006, 12 (5): 523-531. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00651.x.

Vrijhoef HJM, Van Den Bergh JHAM, Diederiks JPM, Weemhoff I, Spreeuwenberg C: Transfer of care for outpatients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease from respiratory care physician to respiratory nurse–a randomized controlled study. Chronic Illn. 2007, 3 (2): 130-144. 10.1177/1742395307081733.

van Wetering CR, Hoogendoorn M, Mol SJM: Rutten-van Molken M, Schols AM: Short- and long-term efficacy of a community-based COPD management programme in less advanced COPD: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2010, 65 (1): 7-13. 10.1136/thx.2009.118620.

Sochalski J, Jaarsma T, Krumholz HM, Laramee A, McMurray JJV, Naylor MD, Rich MW, Riegel B, Stewart S: What works in chronic care management: the case of heart failure. Health Aff. 2009, 28 (1): 179-189. 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.179.

Morales-Asencio JM, Martin-Santos FJ, Morilla-Herrera JC, Cuevas Fernandez-Gallego M, Celdran-Manas M, Navarro-Moya FJ, Rodriguez-Salvador MM, Munoz-Ronda FJ, Gonzalo-Jimenez E, Millan Carrasco A: Design of a case management model for people with chronic disease (Heart Failure and COPD). Phase I: modeling and identification of the main components of the intervention through their actors: patients and professionals (DELTA-icE-PRO Study). BMC Heal Serv Res. 2010, 10: 324-10.1186/1472-6963-10-324.

Martin C, Sturmberg J: Complex adaptive chronic care. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009, 15 (3): 571-577. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.01022.x.

Simpson AC, Rocker GM: Advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: rethinking models of care. Qjm-an Int J Med. 2008, 101 (9): 697-704. 10.1093/qjmed/hcn087.

Wagner EH: Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness?. Eff Clin Prac: ECP. 1998, 1 (1): 2-4.

Adams SG, Smith PK, Allan PF, Anzueto A, Pugh JA, Cornell JE: Systematic review of the chronic care model in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease prevention and management. Arch Intern Med. 2007, 167 (6): 551-561. 10.1001/archinte.167.6.551.

Momentum: Momentum. [http://www.momentum.nhs.uk/momentum/index.html]

Murphy M, Black N, Lamping D, McKee C, Sanderson C, Askham J, Marteau T: Consensus development methods, and their use in clincial guideline development. Health Technol Assess. 1998, 2: 3.

Resource library: http://www.improvingchroniccare.org/index.php?p=Graphics&s=164.

The chronic care model: http://www.improvingchroniccare.org/index.php?p=Model_Elements&s=18.

About ICIC and our work: http://www.improvingchroniccare.org/index.php?p=ACIC_Survey&s=35.

Akins RB, Tolson H, Cole BR: Stability of response characteristics of a Delphi panel: application of bootstrap data expansion. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005, 5: 37-10.1186/1471-2288-5-37.

Hsu C-C, Sanford BA: Minimizing non-response in the Delphi process: How to respond to non-response. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2007, 12 (17): 17-electronic journal

Jones J, Hunter D: Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ. 1995, 311: 376-380. 10.1136/bmj.311.7001.376.

Akins RB, Tolson H, Cole BR: Stability of response characterisatics of a Delphi panel: application of bootstrap data expansion. BMC Heal Serv Res. 2005, 5 (37).

Hansson R, Keeney S, McKenna H: Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000, 32 (4): 1008-1015.

Dennis SM, Zwar N, Griffiths R, Roland M, Hasan I, Davies GP, Harris M: Chronic disease management in primary care: from evidence to policy. Med J Aust. 2008, 188 (8): S53-S56.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/12/193/prepub

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Edward Konunga for reviewing earlier drafts of this paper. We are also thankful to the panel members’ contributions. This research was funded through an infrastructure grant from NHS County Durham and Darlington.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

EH and GR designed the study analysed the results. EH collected the data. EH and GR prepared, read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Henderson, E.J., Rubin, G.P. Development of a community-based model for respiratory care services. BMC Health Serv Res 12, 193 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-193

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-193