Abstract

Background

Physicians are encouraged to counsel obese patients to lose weight, but studies measuring the quality of physicians' counseling are rare. We sought to describe the quality of physicians' obesity counseling and to determine associations between the quality of counseling and obese patients' motivation and intentions to lose weight, key predictors of behavior change.

Methods

We conducted post-visit surveys with obese patients to assess physician's use of 5As counseling techniques and the overall patient-centeredness of the physician.. Patients also reported on their motivation to lose weight and their intentions to eat healthier and exercise. One-way ANOVAs were used to describe mean differences in number of counseling practices across levels of self-rated intention and motivation. Logistic regression analyses were conducted to assess associations between number of 5As counseling practices used and patient intention and motivation.

Results

137 patients of 23 physicians were included in the analysis. While 85% of the patients were counseled about obesity, physicians used only a mean of 5.3 (SD = 4.6) of 18 possible 5As counseling practices. Patients with higher levels of motivation and intentions reported receiving more 5As counseling techniques than those with lower levels. Each additional counseling practice was associated with higher odds of being motivated to lose weight (OR 1.31, CI 1.11-1.55), intending to eat better (OR 1.23, CI 1.06-1.44), and intending to exercise regularly (OR 1.14, CI 1.00-1.31). Patient centeredness of the physician was also positively associated with intentions to eat better (OR 2.96, CI 1.03-8.47) and exercise (OR 26.07, CI 3.70-83.93).

Conclusions

Quality of physician counseling (as measured using the 5As counseling framework and patient-centeredness scales) was associated with motivation to lose weight and intentions to change behavior. Future studies should determine whether higher quality obesity counseling leads to improved behavioral and weight outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

There is consensus that physicians should counsel obese patients to lose weight [1–4]. Physician weight loss counseling is generally positively associated with self-reported behavior change in patients [5–7], but the quality of physician counseling is rarely assessed [8]. Physicians often fail to counsel obese patients [5, 9–12] and, when counseling occurs, it is often of poor quality. In one study, of patients who reported discussing their weight, only 5% received diet and exercise advice [6]. Potential reasons why physicians do not adequately counsel patients include lack of time [13], poor training/competency [14–18], and negative attitudes about obesity [19–22].

The 5As counseling framework has been proposed as a way to teach and evaluate the quality of obesity counseling [8, 16, 23, 24]. The 5As framework guides the physician to Assess risk, current behavior, and readiness to change, Advise change of specific behaviors, Agree and collaboratively set goals, Assist in addressing barriers and securing support, and Arrange for follow-up [8, 16, 23, 25]. Training physicians about this framework has been shown to improve patient outcomes in smoking cessation [26]. When combined with office management strategies, training physicians to use the 5As was found to produce greater lipid control and weight loss [27] in patients.

In addition to the 5As model, patient-centeredness is an important measure of the quality of the patient-physician interaction. Patient-centeredness can be defined as being responsive to a patients' needs, beliefs, values, and preferences [28]. An example of a patient-centered counseling strategy would be to discuss weight loss goals in the context of a patients' individual reasons for wanting to lose weight (well-being vs. appearance vs. improvement of diabetes control, etc.). Patient-centeredness is endorsed by patients [29] and associated with increased patient satisfaction and improved health outcomes [30, 31].

The purpose of this study was to explore how quality of obesity counseling may lead to behavior change in obese patients. We used adherence to the 5As model and patient-centeredness as our main quality measures. We chose motivation and intention as intermediary patient outcomes since they are key elements of evidence based behavior change models [32] and have been shown to be determinants of behavior change in the setting of weight control [33–35]. In order to determine the potential impact of the quality of physicians' obesity counseling on these variables, we surveyed obese patients immediately after their visit with their physician. We focused on a cohort of residents with varied exposure to training in order to address the questions of whether quality of counseling, regardless of training, is associated with intermediary outcomes. We hypothesized that the quality of physicians' obesity counseling would be associated with higher patient motivation to lose weight as well as stronger intentions to change their diet and exercise behaviors.

Methods

Subjects

Residents

We included all 23 primary care resident physicians at New York University. They all had consented to be part of a medical education research registry approved by the Institutional Review Board at New York University. The residents were part of a non-randomized study to look at the impact of a 5-hour obesity counseling training on quality of counseling and markers of behavior change in patients. Eleven of the residents received the curriculum and 12 did not. Besides the curriculum, the residency program already emphasized behavior change counseling skills, so there was substantial overlap in the distribution of quality of counseling between the curriculum and non-curriculum groups. Thus, for the purpose of this paper's exploration of links between counseling and patient motivations and intentions, regardless of differences in physician training, the residents and their patients were evaluated in aggregate.

Patients and Procedures

We invited all adult, English and Spanish-speaking obese (body mass index(BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2) patients (≥18 years) seen by primary care residents at Gouverneur Healthcare Services to participate in this study. This clinic is part of the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation (HHC). Gouverneur is located in the Lower East Side of Manhattan and serves a largely low income, underserved immigrant population. Fifteen nursing staff identified English and Spanish-speaking patients with a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2. Research assistants approached these patients immediately after their visit with their physician to invite them to be part of the study. Because low health literacy is common in this setting, all the patients provided verbal consent to be interviewed after listening to a consent script. Research assistants then verbally adminsitered a 30-minute structured survey to each patient in a separate room. They explicitly assured the patients that their physician would not be made aware of the answers. Participants received a pedometer (approximate value = $3.30) as compensation. We excluded patients during analysis if their chief complaint (determined during chart abstraction) indicated they had an acute visit (pain, fever, infectious disease, upper respiratory tract infection, shortness of breath, palpitations, dizziness) as we believe that these immediate needs take priority over obesity counseling, that physicians are therefore not likely to have sufficient time to address obesity in the context of an acute complaint, and that patient's receptivity to obesity counseling is negatively impacted if the patient has discomfort or distress. We also excluded patients during analysis who were incorrectly identified by nursing staff as obese or high risk --i.e. did not have a BMI that rounded to a whole number ≥ 30. To preserve sample size, we kept patients who had a BMI ≥27 with diabetes or 2 or more co-morbidities where weight loss counseling was indicated as per National Institute of Health guidelines[36].

Measures

Body Mass Index

Nursing staff were trained to take height and weight measurements and to calculate BMI. Weight was measured in pounds (rounded to the nearest half pound) using one of 4 calibrated analog scales each equipped with a stadiometer used to take height measurements in inches (rounded to the nearest half inch) with the patients fully clothed except for shoes and jackets. BMI was calculated using the formula BMI = (weight in lbs *703)/(height in inches)2.

Structured Interview Instrument

We developed a structured interview, conducted by a research assistant and fielded in both English and Spanish, to ensure full and accurate participation of low literacy patients and to assess the core variables of interest [Additional File 1]. We piloted the survey with 20 patients in both Spanish and English to ensure that the questions were understandable, culturally appropriate, and accurately translated into Spanish. Each interview took 30 minutes to complete.

Physicians' use of the 5As of obesity counseling was measured by asking patients whether the physician performed 18 literature-derived 5A's-related counseling skills (e.g. Assess: "Did your doctor ask whether you are currently trying to lose weight?"; Advise: "Did your doctor advise you to lose weight?"; Assist: "did your doctor help you set goals to improve your diet and/or exercise more?") [8, 23, 25]. The exact questions are published [8, Additional File 1]; the one difference is that we omitted the question "Did you and your doctor discuss your weight today?" since we wanted to focus on quality of counseling. The Cronbach's alpha for these items was 0.89 showing excellent internal consistency. We have also used similiar items in observed structured clinical exams (OSCEs) to evaluate physician performance with adequate internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha = .78).

Finally, we measured theory-based patient, visit, and physician factors that we hypothesized would influence motivation, and intention independent of the quality of physician counseling or that might influence perceptions of the quality of counseling. Patient variables included BMI, gender, primary language, perceived health status, number of co-morbidities, medications, health literacy, self efficacy, and current weight loss, diet and exercise behaviors. Health literacy was assessed using 2 screening questions about ability to read and complete health-related documents [37]. We assessed patients' stage of change by asking participants how true the statement "In the past month, I have been actively trying to lose weight" (or "not gain weight") was of them. We assessed self efficacy to eat healthier and exercise by asking patients to rate their confidence do these things on a 4-pt Likert scale. Current dietary behavior was assessed by averaging responses on 2 statements; "I usually control portions" and "I usually pay attention to fat in my diet" (both using the same 4-point scale). Type of visit was categorized as whether or not this was the patient's first visit with this physician and the interview also assessed whether the physician had advised this patient to lose weight in the past. We measured the patient-centeredness of the physician using six questions adapted from the RAND Corporation Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire [38] and the OPTION (observing patient involvement) shared decision-making scales [39].

Motivation to lose weight was assessed with a direct question --"How motivated are you to lose weight?" [40] and participants responded using a 4-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 2 = only a little, 3 = somewhat motivated, 4 = very motivated). Intentions were assessed separately for eating and exercise behavior change by asking patients to indicate how true (1 = not at all true, 4 = very true) each of the following statements were of them: "in the next month, I have specific plans to eat healthier" and "in the next month, I have specific plans to exercise". These intention items were developed based on Ajzen's guidelines for writing behavioral intention items in terms of being specific as to target behavior and time frame and then piloted as recommended [41].

For the logistic regression analyses and given that motivations and intentions were both positively skewed, motivation was dichotimized into "very" movivated or less than very motivated and the intention variables were dichotomized into "very true of me" or less (not at all, only a little, somewhat).

Statistical Analysis

We used means and frequencies to describe our patient sample. Distributions were reported for our dependent variables: motivation and intentions. A "5As counseling score" was calculated as the number of all eighteen 5As skills reported by the patient to have been performed during the visit. We averaged the score of the 7 patient-centeredness items to arrive at a patient-centeredness score. Oneway ANOVAs with Bonferroni post-hoc analysis of pairwise differences were used to assess mean differences in the number of 5As counseling skills by the rated level of motivation and intentions. Finally, logistic regressions were used to explore associations between quality of obesity counseling and the 3 dichotomized outcome variables: whether patients were highly motivated to lose weight, whether it was "very true" that patients had a specific plan to eat better and to exercise regularly in the next month. Potential confounders were included in the logistic regression model and were selected based on whether they were likely to be independently associated with patients' motivation and intentions.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at New York University School of Medicine and Gouverneur Healthcare Services.

Results

The nursing staff identified 190 patients through BMI screening. After 28 declined (mostly due to time constraints) and 4 were excluded (non-English or Spanish speaking patients), we interviewed 158 patients of 23 primary care medicine residents from all 3 post-graduate (PGY) years (8 PGY 1, 8 PGY 2, 7 PGY 3). We excluded 4 patients who did not ultimately meet the BMI criteria. Seventeen patients were excluded after the chart abstraction indicated that they had an acute visit, leaving a final sample of 137patients. The mean number of patients per resident was 6.0 (SD = 4.1, range = 1-14).

Table 1 shows the patient characteristics. Of note, the majority of the patients were female and Hispanic. More than half were of low health literacy. Mean self perceived health status was in the fair to good range. More than a third reported actively trying to lose weight and most had high self-efficacy in the areas of eating well and especially exercising regularly. Over half of the visits were first visits and in 29.2% of the visits, the patient had previously been advised to lose weight by this visit's physician.

Table 2 shows patients' responses about their motivation to lose weight and intentions to eat better and get more exercise. The majority of patients were somewhat or very motivated to lose weight and endorsed that they had specific plans to eat healthier and exercise.

Table 3 shows the percentage of patients counseled about weight loss, diet, or exercise and the mean number of counseling practices delivered by the physicians (in aggregate and broken down by the 5As). The vast majority of patients received some form of counseling, but the average number of 5As practices was low. "Assess" skills occurred most, followed by Advise practices. Agree, Assist, and Arrange practices were reported to be used, on average, less than once per visit.

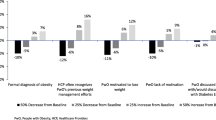

Table 4 shows the number of 5As obesity counseling practices by patients' motivation level and intention to eat better and exercise. Based on posthoc follow-up on a significant overall F value with Bonferroni corrections, significant differences in obesity counseling scores were found between those who reported being "only a little" motivated to lose weight and those who were "very motivated" to lose weight. Patients for whom it was "very true" that they had a specific plan to eat better reported significantly more counseling practices than those for whom this statement was less true. In terms of having a plan to exercise regularly, those who felt that this was "somewhat" or "very" true of them reported almost three times as many counseling practices as those who reported that this "not at all" true of them.

Table 5 shows the results of 3 logistic regression models with dichotomized motivation to lose weight, intention to eat healthier, and intention to exercise each as the dependent variable. Each additional counseling practice was associated with higher odds of being very motivated to lose weight and intending to eat healthier and exercise. Patient centeredness was associated with higher odds of intending to eat better and exercise regularly indicating that how counseling skills are practiced may also be important. Patient and visit characteristics were not significantly associated with motivation and intention, with the exceptions of age (for motivation) and actively trying to lose or maintain weight (for intention to eat better). The odds ratio for self-efficacy to exercise, while not significant, suggests that increases in self-efficacy may be associated with greater intention to exercise.

Discussion

In this study, we found that resident physicians counseled most of their obese patients about weight. However, they used only a handful of possible 5As skills as part of obesity counseling. Much of the focus of the counseling appeared to involve assessing rather than assisting or arranging. The number of 5As counseling practices reported by the patient to have occurred during the visit was associated with patient motivation to lose weight and intention to change diet and exercise behavior, supporting our hypothesis that higher quality physician counseling may lead to increased motivation and intention to lose weight. An alternative explanation is that patients with higher levels of motivation and intentions are more likely to elicit physician counseling practices and/or report that their physician counseled them. The cross-sectional nature of our study limits our ability to determine the direction of this relationship and future studies are necessary.

If higher quality physician counseling indeed influenced patients' motivation and intentions, then this study highlights theory-based mechanisms through which specific counseling skills can potentially influence patient behavior change. While we were not able to measure actual behavior change or weight loss in this cross-sectional study, we established links between physician counseling practices and important intermediary markers of behavior change. A randomized controlled trial of an intervention to form intentions (or specific plans) in patients attending a commercial weight loss program produced twice the amount of weight loss at 2 months compared with controls [42]. Motivational interviewing, which is done to increase patients' intrinsic motivation to perform a behavior, has been shown to help patients exercise and lose weight [43, 44]. By examining motivation and intention, we can better understand potential mechanisms through which physician counseling may play a role in affecting patient behavior.

That the patient-centeredness of the physician was strongly associated with patient intentions suggests that how counseling skills are delivered matters and that quality of the physician/patient relationship may influence the patients' commitment to behavior change. The large odds ratios we found for patient-centeredness may, in part, reflect the lack of variation in this variable which was skewed quite positively and had a low standard deviation. However, we also believe that they reflect the importance of providing patient-centered care in combination with 5As skills to counsel patients to lose weight and change their behaviors. While use of the 5As is considered to be a patient-centered approach to counseling [24], we believe that these are distinct measures since use of the 5As counseling practices leads to higher odds of being motivated and having intentions to change behavior even after controlling for patient centeredness.

There are several limitations to our study. First, generalizability of our findings is limited because we studied a relatively small sample of patients who are mostly underserved, Hispanic patients of physician trainees from a single public clinic. The findings may differ in other populations. Our measure of physicians' use of the 5As is patient-reported and has not been validated with direct observation. The patients' responses may therefore not directly reflect actual physician behavior. Despite this, we believe that patient report and recall of physician counseling may be more important than whether such counseling was directly observed. Also, delivery of the 5As may occur over several visits and it may not be fair to assess quality of physicians' obesity counseling after a single visit. Even more importantly, quality of physician counseling had small effects, in line with those found in similar studies [33] , suggesting that one visit is insufficient for making dramatic differences in obese patients' orientation to behavior change. Finally, this cross sectional study cannot determine causality or assess the directionality of the associations. An alternative interpretation of our results may be that more motivated patients are more likely to receive higher quality obesity counseling. Thus, longitudinal studies and randomized controlled trials are needed to determine whether there is a sustained impact of physician counseling on behavior change in obese patients.

Despite these limitations, this study may inform how we teach physicians to counsel obese patients. Medical school and residency programs already have incorporated patient-centeredness into their curriculums [45–47], and this study supports this approach for obesity counseling. Some authors (including us) propose teaching the 5As to residents for obesity, diet, and exercise counseling [16, 24], and we found that each additional 5As-related counseling practice was associated with better outcomes. Future studies should examine the impact of training residents on patient outcomes.

Conclusions

Use of the 5As counseling practices and delivery of patient-centered care are both markers of quality of obesity counseling. Physicians' use of the 5As is associated with higher odds of patient motivation to lose weight, intention to eat healthier, and intention to exercise. Patient centeredness is also strongly associated with intentions to change behavior. Future studies need to determine whether higher quality obesity counseling leads to actual changes in patient behavior and weight loss and whether teaching physicians patient-centered care and 5As leads to improvement in patient outcomes.

References

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: Screening for obesity in adults: recommendations and rationale. See comment. Ann Intern Med. 2003, 139 (11): 930-932.

Grundy SM, Balady GJ, Criqui MH, Fletcher G, Greenland P, Hiratzka LF, Houston-Miller N, Kris-Etherton P, Krumholz HM, LaRosa J, Ockene IS, Pearson TA, Reed J, Washington R, Smith SC: Guide to primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases. A statement for healthcare professionals from the Task Force on Risk Reduction. American Heart Association Science Advisory and Coordinating Committee. Circulation. 1997, 95: (9):2329-2331.

Klein S, Sheard NF, Pi-Sunyer X, Daly A, Wylie-Rosett J, Kulkarni K, Clark NG, American Diabetes A, North American Association for the Study of American Society for Clinical N: Weight management through lifestyle modification for the prevention and management of type 2 diabetes: rationale and strategies. A statement of the American Diabetes Association, the North American Association for the Study of Obesity, and the American Society for Clinical Nutrition. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004, 80 (2): 257-263.

Barlow SE, Dietz WH: Obesity evaluation and treatment: Expert Committee recommendations. The Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration and the Department of Health and Human Services. Pediatrics. 1998, 102 (3): E29-10.1542/peds.102.3.e29.

Loureiro ML, Nayga RM: Obesity, weight loss, and physician's advice. Soc Sci Med. 2006, 62 (10): 2458-2468. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.011.

Huang J, Yu H, Marin E, Brock S, Carden D, Davis T: Physicians' weight loss counseling in two public hospital primary care clinics. Academic Medicine. 2004, 79 (2): 156-161. 10.1097/00001888-200402000-00012.

Stafford RS, Farhat JH, Misra B, Schoenfeld DA: National patterns of physician activities related to obesity management. Arch Fam Med. 2000, 9 (7): 631-638. 10.1001/archfami.9.7.631.

Jay M, Schlair S, Caldwell R, Kalet A, Sherman S, Gillespie CC: From the patients' perspective: The impact of training on resident physicians' obesity counseling. JGIM. 2010, 25 (5): 415-422. 10.1007/s11606-010-1299-8.

Scott JG, Cohen D, DiCicco-Bloom B, Orzano AJ, Gregory P, Flocke SA, Maxwell L, Crabtree B: Speaking of weight: how patients and primary care clinicians initiate weight loss counseling. Prev Med. 2004, 38 (6): 819-827. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.01.001.

Nawaz H, Adams ML, Katz DL: Weight loss counseling by health care providers. Am J Public Health. 1999, 89 (5): 764-767. 10.2105/AJPH.89.5.764.

Ruser CB, Sanders L, Brescia GR, Talbot M, Hartman K, Vivieros K, Bravata DM: Identification and management of overweight and obesity by internal medicine residents. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2005, 20 (12): 1139-1141. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0263.x.

O'Brien SH, Holubkov R, Reis EC: Identification, evaluation, and management of obesity in an academic primary care center. Pediatrics. 2004, 114 (2): e154-9. 10.1542/peds.114.2.e154.

Kushner RF: Barriers to providing nutrition counseling by physicians: a survey of primary care practitioners. Prev Med. 1995, 24 (6): 546-552. 10.1006/pmed.1995.1087.

Kristeller JL, Hoerr RA: Physician attitudes toward managing obesity: differences among six specialty groups. Prev Med. 1997, 26 (4): 542-549. 10.1006/pmed.1997.0171.

Davis DA, Mazmanian PE, Fordis M, Van Harrison R, Thorpe KE, Perrier L: Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: a systematic review.[see comment]. JAMA. 2006, 296 (9): 1094-1102. 10.1001/jama.296.9.1094.

Jay M, Gillespie C, Ark T, Richter R, McMacken M, Zabar S, Paik S, Messito M, Lee J, Kalet A: Do Internists, Pediatricians, and Psychiatrists Feel Competent in Obesity Care? Using a Needs Assessment to Drive Curriculum Design. JGIM. 2008, 23 (7): 1066-1066-1070. 10.1007/s11606-008-0519-y.

Block JP, DeSalvo KB, Fisher WP: Are physicians equipped to address the obesity epidemic? Knowledge and attitudes of internal medicine residents. Prev Med. 2003, 36 (6): 669-675. 10.1016/S0091-7435(03)00055-0.

Fogelman Y, Vinker S, Lachter J, Biderman A, Itzhak B, Kitai E: Managing obesity: a survey of attitudes and practices among Israeli primary care physicians. International Journal of Obesity & Related Metabolic Disorders: Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2002, 26 (10): 1393-1397. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802063.

Foster GD, Wadden TA, Makris AP, Davidson D, Sanderson RS, Allison DB, Kessler A: Primary care physicians' attitudes about obesity and its treatment. Obes Res. 2003, 11 (10): 1168-1177. 10.1038/oby.2003.161.

Jay M, Kalet A, Ark T, McMacken M, Messito M, Richter R, Schlair S, Sherman S, Zabar S, Gillespie C: Physicians' attitudes about obesity and their relation to competency and patient weight loss: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Health Services Research. 2009, 9 (1): 106-10.1186/1472-6963-9-106.

Teachman BA, Brownell KD: Implicit anti-fat bias among health professionals: is anyone immune?. International Journal of Obesity & Related Metabolic Disorders: Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2001, 25 (10): 1525-1531. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801745.

Jelalian E, Boergers J, Alday CS, Frank R: Survey of physician attitudes and practices related to pediatric obesity. Clin Pediatr. 2003, 42 (3): 235-245. 10.1177/000992280304200307.

Serdula MK, Khan LK, Dietz WH: Weight loss counseling revisited. JAMA. 2003, 289 (14): 1747-1750. 10.1001/jama.289.14.1747.

Glasgow RE, Emont S, Miller DC: Assessing delivery of the five 'As' for patient-centered counseling. Health Promot Internation. 2006, 21 (3): 245-255. 10.1093/heapro/dal017.

Whitlock EP, Orleans CT, Pender N, Allan J: Evaluating primary care behavioral counseling interventions: An evidence-based approach. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002, 22 (4): 267-284. 10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00415-4.

Unrod M, Smith M, Spring B, DePue J, Redd W, Winkel G: Randomized controlled trial of a computer-based, tailored intervention to increase smoking cessation counseling by primary care physicians. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007, 22 (4): 478-484. 10.1007/s11606-006-0069-0.

Ockene IS, Hebert JR, Ockene JK, Merriam PA, Hurley TG, Saperia GM: Effect of training and a structured office practice on physician-delivered nutrition counseling: the Worcester-Area Trial for Counseling in Hyperlipidemia (WATCH). Am J Prev Med. 1996, 12 (4): 252-258.

Epstein RM, Franks P, Fiscella K, Shields CG, Meldrum SC, Kravitz RL, Duberstein PR: Measuring patient-centered communication in patient-physician consultations: theoretical and practical issues. Soc Sci Med. 2005, 61 (7): 1516-1528. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.02.001.

Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, Warner G, Moore M, Gould C, Ferrier K, Payne S: Preferences of patients for patient centred approach to consultation in primary care: observational stud. BMJ. 2001, 322 (7284): 468-472. 10.1136/bmj.322.7284.468.

Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, McWhinney IR, Oates J, Weston WW, Jordan J: The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000, 49 (9): 796-804.

Stewart MA: Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1995, 152 (9): 1423-1433.

Ajzen I, Fishbein M: Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social behavior. 1980, Prentice-Hall

Teixeira PJ, Going SB, Sardinha LB, Lohman TG: A review of psychosocial pre-treatment predictors of weight control. Obesity Reviews. 2005, 6 (1): 43-65. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00166.x.

Edell BH, Edington S, Herd B, O'Brien RM, Witkin G: Self-efficacy and self-motivation as predictors of weight loss. Addict Behav. 1987, 12 (1): 63-66. 10.1016/0306-4603(87)90009-8.

Schifter DE, Ajzen I: Intention, perceived control, and weight loss: an application of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1985, 49 (3): 843-851. 10.1037/0022-3514.49.3.843.

Anonymous Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults--The Evidence Report. National Institutes of Health. Obes Res. 1998, 6 (Suppl 2): 51S-209S.

Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ: Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med. 2004, 36 (8): 588-594.

Ware J, Snyder M, Wright W: Development and Validation of Scales to Measure Patient Satisfaction with Medical Care Services. Vol I, Part B: Results Regarding Scales Constructed from the Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire and Measures of Other Health Care Perceptions. 1976, Springfield, VA: National Technical Information Service

Elwyn G, Edwards A, Wensing M, Hood K, Atwell C, Grol R: Shared decision making: developing the OPTION scale for measuring patientinvolvement. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003, 12 (2): 93--99. 10.1136/qhc.12.2.93.

Befort CA, Greiner KA, Hall S, Pulvers KM, Nollen NL, Charbonneau A, Kaur H, Ahluwalia JS: Weight-related perceptions among patients and physicians: how well do physicians judge patients' motivation to lose weight?. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006, 21 (10): 1086-1090. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00567.x.

Ajzen I: Constructing a TPB Questionnaire: Conceptual and Methodological Considerations (Revised, 2006). 2002, Retrieved April 25, 2010 from, [http://www.people.umass.edu/aizen/pdf/tpb.measurement.pdf]

Luszczynska A, Sobczyk A, Abraham C: Planning to lose weight: randomized controlled trial of an implementation intention prompt to enhance weight reduction among overweight and obese women. Health Psychology. 2007, 26 (4): 507-512. 10.1037/0278-6133.26.4.507.

West DS, DiLillo V, Bursac Z, Gore SA, Greene PG: Motivational interviewing improves weight loss in women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007, 30 (5): 1081-1087. 10.2337/dc06-1966.

Rubak S, Sandbaek A, Lauritzen T, Christensen B: Motivational interviewing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of General Practice. 2005, 55 (513): 305-312.

Boyle D, Dwinnell B, Platt F: Invite, listen, and summarize: a patient-centered communication technique. Academic Medicine. 2005, 80 (1): 29-32. 10.1097/00001888-200501000-00008.

Rouf E, Chumley H, Dobbie A: Patient-centered interviewing and student performance in a comprehensive clinical skills examination: is there an association?. Patient Education & Counseling. 2009, 75 (1): 11-15. 10.1016/j.pec.2008.09.016.

Oh J, Segal R, Gordon J, Boal J, Jotkowitz A: Retention and use of patient-centered interviewing skills after intensive training. Academic Medicine. 2001, 76 (6): 647-650. 10.1097/00001888-200106000-00019.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/10/159/prepub

Acknowledgements

This project was funded in part from HRSA Grant 12-191-1077--Academic Administrative Units in Primary Care and by CDC Grant # 5 T01 CD000146-03--CDC Fellowship in Medicine and Public Health Research. We would also like to thank Jennifer Adams, Sondra Zabar, David Stevens, Mack Lipkin, Alfredo Axtmayer, Evelyn Choudhury, Marc Gourevitch, and Mark Schwartz for their consultation and contributions to this project. This work was presented as an oral abstract presentation at the Society for General Internal Medicine Conference in 2009.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

All of the authors contributed substantially to this project. MJ designed, implemented, and oversaw all aspects of the study and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. CG participated in the design of the survey, the protocol, analyzed the data, and contributed to writing the manuscript. SS participated in the design and implementation of the study and contributed to writing the manuscript. SS participated in the design of the study and helped to edit the manuscript. AK participated in the design and implementation of the study. She also provided feedback and editing to the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12913_2009_1296_MOESM1_ESM.PDF

Additional file 1: 5As Patient Exit Interview Survey. This survey was read to the patients during the exit interviews. (PDF 597 KB)

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Jay, M., Gillespie, C., Schlair, S. et al. Physicians' use of the 5As in counseling obese patients: is the quality of counseling associated with patients' motivation and intention to lose weight?. BMC Health Serv Res 10, 159 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-10-159

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-10-159