Abstract

Background

The measurement of processes and outcomes that reflect the complexity of the decision-making process within specific clinical encounters is an important area of research to pursue. A systematic review was conducted to identify instruments that assess the perception physicians have of the decision-making process within specific clinical encounters.

Methods

For every year available up until April 2007, PubMed, PsycINFO, Current Contents, Dissertation Abstracts and Sociological Abstracts were searched for original studies in English or French. Reference lists from retrieved studies were also consulted. Studies were included if they reported a self-administered instrument evaluating physicians' perceptions of the decision-making process within specific clinical encounters, contained sufficient description to permit critical appraisal and presented quantitative results based on administering the instrument. Two individuals independently assessed the eligibility of the instruments and abstracted information on their conceptual underpinnings, main evaluation domain, development, format, reliability, validity and responsiveness. They also assessed the quality of the studies that reported on the development of the instruments with a modified version of STARD.

Results

Out of 3431 records identified and screened for evaluation, 26 potentially relevant instruments were assessed; 11 met the inclusion criteria. Five instruments were published before 1995. Among those published after 1995, five offered a corresponding patient version. Overall, the main evaluation domains were: satisfaction with the clinical encounter (n = 2), mutual understanding between health professional and patient (n = 2), mental workload (n = 1), frustration with the clinical encounter (n = 1), nurse-physician collaboration (n = 1), perceptions of communication competence (n = 2), degree of comfort with a decision (n = 1) and information on medication (n = 1). For most instruments (n = 10), some reliability and validity criteria were reported in French or English. Overall, the mean number of items on the modified version of STARD was 12.4 (range: 2 to 18).

Conclusion

This systematic review provides a critical appraisal and repository of instruments that assess the perception physicians have of the decision-making process within specific clinical encounters. More research is needed to pursue the validation of the existing instruments and the development of patient versions. This will help researchers capture the complexity of the decision-making process within specific clinical encounters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Practising medicine involves making decisions at all stages of the clinical process [1]. Although a great deal of varied terminology is used to describe doctors' thinking, the term "decision-making process" is used extensively in the medical and healthcare literature [2]. The decision-making process is broadly defined as global judgements by a clinician about the appropriate course of action and is said to be unspecified, as a number of processes may produce a decision [3]. In clinical settings, it is also understood as the use of diverse strategies to generate and test potential solutions to problems that are presented by patients and involves using, acquiring and interpreting the indicators and then generating and evaluating hypotheses [4]. Processes or strategies that will be used may be based on what the clinician was taught, his or her own representation of the evidence supporting each course of action, or the prevailing practice in a given institution [4].

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in new representations of the clinical decision-making process that better address its complexity within specific clinical encounters. Indeed, providing medical care to a patient is now increasingly considered a dynamic and interactive process known as "shared decision-making" [5–7]. Characteristics of shared decision-making include that at least two participants, clinician and patient, be involved; that there be a two-way exchange not only of information but also of treatment preferences; that both parties take steps to build a consensus about the preferred treatment; and that an agreement be reached on the treatment to be implemented [5]. Shared decision-making includes the following components: establishing a context in which patients' views about treatment options are valued and deemed necessary, transferring technical information, making sure patients understand this information, helping patients base their preference on the best evidence; eliciting patients' preferences, sharing treatment recommendations, and making explicit the component of uncertainty in the clinical decision-making process [8].

Shared decision-making does not exclude a consideration of the values and preferences of the physician and occurs through a partnership in which the responsibilities and rights of each of the parties and the benefits for each party are made clear [9]. Given the recognition that patient-physician interactions and by extension, clinical decision-making processes, are dynamic and reciprocal in their nature, it is surprising to find little systematic evaluation of the physicians' perspective of this entity [10]. Consequently, there has been a renewed interest in capturing the perspective of physicians of the decision-making process within specific clinical encounters. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review was to identify instruments that assess the perception of physicians of the decision-making process within specific clinical encounters.

Methods

Search strategy

Covering all years available (to April 2007), we conducted an electronic literature search of the following databases: PubMed, PsycINFO, Current Contents, Dissertation Abstracts and Sociological Abstracts. Three information specialists were consulted to help develop, update and run the search strategy. The following MeSH terms and free text words were used to create specific search strategies for each database: "decision making", "physicians", "health personnel", "doctors", "practitioners", "health personnel attitudes", "measurement", "questionnaire", "psychometrics" and "psychological tests". We included titles of publications and their respective abstract in English or French that potentially included an eligible instrument. Initially, if a dissertation abstract was found along a publication, both were kept. We also contacted 10 experts in the field (list available from authors) and contacted corresponding authors of included instruments. Lastly, we reviewed bibliographies of the included instruments. Once we included an instrument, we conducted an electronic search of the first author.

Selection criteria

All of the searches were downloaded to a reference database for initial screening of titles and abstracts by a single member of the review team. Prior to screening, duplicates were removed from the database. Titles of publications and their respective abstract reporting editorials, letters, surveys, clinical vignettes or the completion of an Objective Structured Clinical Examination or the evaluation of a simulated patient were excluded. After the initial screening, if detailed information about the titles of publications and their respective abstract was questionable, the full text of these publications was sought. Then, two reviewers independently appraised these publications to identify ones that reported on the use or development an eligible instrument. Discrepancies between the two reviewers were resolved through discussion.

Identification of eligible instruments

The following inclusion criteria were applied: 1) a self-administered instrument was presented; 2) the instrument evaluated the perspective of physicians, including residents, of the decision-making process within specific clinical encounters, 3) the collection of data occurred after a specific clinical encounter in a 'real' clinical setting; 4) the report included sufficient description to permit critical appraisal of the instrument (for example, the instrument was provided as an appendix or we were able to get a copy from the author); and 5) there were quantitative results following the administration of the instrument. An instrument was defined as a systematic procedure for the assignment of numbers to aspects of objects, events or persons as indicated by its construction, administration and scoring procedure according to prescribed rules [11].

The outcomes of interest included the perception of physicians of the decision-making process within specific clinical encounters as well as the outcome of the decision itself such as satisfaction with the decision. The decision-making process was defined in an inclusive manner as global judgements by a physician about the appropriate course of action [3]. An instrument was deemed eligible if one of its sub-scales or some of its items tapped into the outcomes of interest.

Data extraction

The data extraction form, derived from McDowell (1987) [12], covered characteristics of the source of information and characteristics of the instrument itself, such as name of the instrument, origin of first author, main purpose, description of the instrument, characteristics of the response scale, presence of a corresponding patient instrument, development procedures, conceptual/theoretical foundation, validity, reliability (e.g. internal consistency) and responsiveness of the instrument.

A conceptual framework was considered to be used if the author referred to a set of concepts and the propositions that integrate them into a meaningful configuration [13]. A theory was deemed to be used if the author referred to a theory, defined as a series of statements that purport to account for or characterize some phenomenon with a much greater specificity that a conceptual framework [13]. Otherwise, the nature of the source of references used by the author was used to identify a broad conceptual basis.

Content validity (i.e. the extent to which all relevant aspects of the domain or area that is being measured are represented in the instrument), construct validity (i.e. the extent to which the instrument relates to other tests or constructs in the way that was expected) and criterion validity (i.e. the extent to which the instrument relates to a gold standard to which it is compared) were also assessed [14]. Responsiveness (i.e. the extent to which the instrument measured change within persons over time) was also assessed [15].

Using the Science Citation Index, we assessed how many times the included instruments had been cited in subsequent published research in French or English. Lastly, for each instrument, we assigned one main evaluation domain defined as a subjective interpretation by the reviewers of the main construct that the instrument was assessing. Sources of disagreement were discussed and resolved by consensus and only consensus data was used. Data extraction was completed by two members of the team.

Quality assessment

The quality of reporting of the included studies was assessed by two reviewers independently, using a modified version of the following instrument, Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD) [16–18]. The original STARD contains 25 items pertaining to study question, study participants, study design, test methods, reference standard, statistical methods, reporting of results and conclusions. However, because we were interested in instruments assessing the perception of physicians of the decision-making process within specific clinical encounters, we added one more item under the section "statistical methods." This new item assessed if the authors of the included instrument had taken into account that one physician could only contribute to one questionnaire for the statistical analyses used to provide evidence on its reliability and validity (i.e., the non-independence of data). For each instrument, we chose one main study. In instruments for which more than one report was included, we chose the one that reported the most details on the development and psychometrics of the instrument in its most recent version.

Results

Included instruments

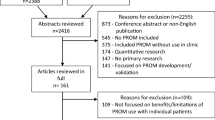

The initial search resulted in 3431 records (Figure 1). From these, 192 records that were in a language other than French or English, and 138 duplicates were removed. After applying our eligibility criteria, 218 full text articles were retrieved for detailed evaluation. Twenty-six instruments (67 articles) were potentially eligible of which a further 15 (28 articles) were excluded because they were not designed to collect data for a specific clinical encounter [19–46]. Therefore, 11 instruments (39 articles) were included [47–85]. We were able to get access to a published version or a copy of all included instruments.

Characteristics of the included instruments

Overall, the included instruments were published between 1986 and 2007 (Table 1) [47–85]. Nine instruments were developed in North America and available in English [47–67, 69–72, 74–85]. Among these, three were available in French [57, 58, 64–67, 69–71, 77–82]. Two instruments were developed in Europe [68, 73]. For most instruments, the first author was affiliated with a Faculty of Medicine or a medical organisation (n = 8) [54–59, 64–72, 74, 76–85], followed by a School of Nursing (n = 1) [47–53, 75], Department of Communication (n = 1) [60–63] and Research Group in Psychosomatic Rehabilitation (n = 1) [73]. Most instruments were developed for non-specific clinical problems (n = 9) [54–74, 76, 83–85]. One instrument was developed for intensive care unit-related problems [47–53, 75] and one for inflammatory bowel diseases [77–82].

All instruments were multi-dimensional. The mean number of items per instrument was 16.7 (range: 6 to 37). Seven instruments used a Likert response scale [47–54, 57, 58, 60–67, 69–72, 75, 76, 83–85], two used a Visual Analog Scale [55, 56, 59, 74, 77–82] and one used a 5-point categorical response scale [73]. One instrument used a mix of response scales [68]. Five instruments offered a patient version [57, 58, 60–71, 77–82].

Based on the Science Citation Index, nine instruments had been cited at least once in subsequent research published in French or English with the older ones being more likely to be cited more often (Spearman r = -0.68; p = 0.03).

Development procedures and psychometrics of the included instruments

Authors of nine instruments reported on their explicit use of some conceptual framework or broad conceptual domain (Table 2) [47–53, 55–75, 77–82]. For seven instruments, we were able to find evidence of their validity and reliability [47–67, 69–71, 74–76, 83–85]. For two instruments, evidence of validity and reliability data was available only for the combined use of the physician's and patient's questionnaires [68, 77–82]. For one instrument, we could not find evidence of validity and reliability data published in French or English [73].

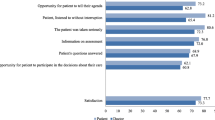

None of the instruments provided data on their responsiveness (i.e. the extent to which it measures change within a physician over time). Lastly, the main evaluation domain that was assigned to each instrument were: satisfaction with the clinical encounter (n = 2) [54, 76, 83–85], mutual understanding between the health professional and the patient (n = 2) [68, 77–82], mental workload (n = 1) [55, 56, 59, 74], frustration with the clinical encounter (n = 1) [72], nurse-physician collaboration (n = 1) [47–53, 75], perceptions of communication competence (n = 2) [58, 60–63], degree of comfort with a decision (n = 1) [57, 64–67, 69–71] and information on medication (n = 1) [73].

Quality of the studies that reported on the included instruments

Overall, the mean number of items reported on the modified STARD was 12.4 (range: 2 to 18}(Table 3). During the development of four instruments, the authors used an analytical approach that took into account the non-independence of data [47–53, 55–57, 59, 64–67, 69–71, 74, 75, 84, 85]. For the Mental Work-Load Instrument, the authors used a mean score per physician to perform the correlation analyses [55, 56, 59, 74]. For the Physician Satisfaction Questionnaire, the authors used a bootstrapping approach to perform the factor analysis [84, 85]. For the Collaboration and Satisfaction about Care Decisions instrument, the authors restricted their sample size to one data entry per physician (n = 56) to perform most of their analyses [47–53, 75] and for the Provider Decision Process Assessment Instrument, the authors used a bootstrapping approach to perform their reliability analyses (i.e. Cronbach alpha) [57, 64–67, 69–71].

Discussion

We believe that the results of this systematic review are important. First, they indicate that there is an interest expressed by clinicians, health services researchers and educators in assessing the perspective of physicians about the processes leading to a decision within specific clinical encounters. This is congruent with the increasing number of randomized trials and systematic reviews examining the efficacy of interventions designed to bring about a change in clinical practice [86]. However, most of these trials assessed a change in health professionals' behaviour without assessing the underlying decision-making process that lead to such behavioural change. This review provides a list of standardized measures of the physician perspective of the clinical decision-making process, an essential step prior to behavioural change. Moreover, most of the included instruments provided some account of their conceptual or theoretical underpinnings. This is important because more attention needs to be given to the combination of different theories that could help us understand professional behaviours [87–90]. Therefore, this review provides health services researchers and educators with a set of standardized and theory-driven instruments that have the potential to improve the quality of implementation studies and by extension our understanding of health professionals' behaviour changes.

Second, this review provides evidence that health services researchers are beginning to use a dyadic and relationship-centered approach to clinical decision-making [91–93]. In other words, health services researchers are moving from studying groups of patients and health professionals separately to studying both simultaneously. For example, five of the six most recently developed instruments had corresponding patient versions [57, 58, 60–71, 77–79, 81, 82]. Moreover, for the authors of two of these instruments, evidence of validity and reliability data was available only for the combined use of the physician's and patient's questionnaires [68, 77–82]. This observation suggests that, increasingly, the clinical decision-making process is perceived as not being dissociable from the complex aspects of interdependence occurring between the physician and the patient. Indeed, the patient-physician relationship is an important component of physicians' satisfaction with their job [93]. Physicians' judgements about their experience with individual patients both reflect and shape what takes place during office visits and beyond [84]. This symmetry supports empirically what has previously been described on the basis of personal needs, namely, that both the physician and the patient have the same human needs for connection which can be fulfilled in the clinical encounter [84]. Therefore, future research in the field of clinical decision-making should foster the use of patient and physician versions of a similar instrument. In line with the growing interest for shared decision-making, this may allow for a more comprehensive assessment of the complexity of the clinical decision-making process and thus of its dynamic and reciprocal nature [65].

Third, this review highlights the need for further methodological development in studies assessing the perception of physicians of the decision-making process within specific clinical encounters. None of the authors of the included instruments provided data on the responsiveness of their instruments (i.e. the extent to which the instrument measures physician change over time). Also, 'within physician' clustering of multiple data points (i.e. non-independence of data) produced statistical challenges that were dealt with inconsistently by their developers. In one instrument, clustering of multiple data point under each physician was taken into account for the factorial analysis but not for the reliability analyses [84, 85]. Authors who took clustering into consideration used one of three strategies: average score per physician [55, 56, 59, 74], one data entry per physician [47–53, 75] or bootstrapping [57, 64–67, 69–71, 84, 85]. Therefore, methodological development in this area will be needed to ensure that responsive instruments and adequate analytical approaches are used in studies assessing the perception of physicians of the decision-making process within specific clinical encounters.

Lastly, for the included instruments, the mean number of items ranged from 6 to 37 items (mean = 16.7). It remains a challenge for health service researchers to develop sound measurements for conducting implementation studies that will minimize the burden to participating physicians. In our own experience, and in line with what has been reported in the literature, there appears to be an association between instrument length, defined in this systematic review as the number of items included in an instrument, and physician participation in studies [94]. This is perhaps even more apparent for health professionals' self-administered questionnaires after a specific clinical encounter. As such, our results provide some valuable insight or benchmarking about the number of items included in the instruments that are currently available for conducting studies on clinical decision-making with physicians.

This review has a number of limitations. Studies reporting the development of instruments are generally not well-indexed in electronic databases [95]. In this review, the search strategies used may not have been optimal even though we consulted with three experienced information specialists. It is possible that some eligible instruments as well as relevant publication regarding the included instruments were not included in this review. Also, clinical decision-making is moving from a unidisciplinary perspective to an interdisciplinary perspective [20]. Therefore, the included instruments might not be representative of on-going developments in healthcare decision-making. Indeed, recent health services policy documents clearly indicate the need for patient-centered care provided by an interprofessional team [96]. However, in a review on barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision making in clinical practice as perceived by health professionals, the vast majority of participants (n = 2784) enrolled in the 28 included studies were physicians (89%) [97]. This suggests that more will need to be done to enhance an interprofessional perspective to shared decision making, a process by which a patient and his/her healthcare providers engage in a decision-making process. We firmly believe that the instruments that were identified throughout this review could be further developed using this interprofessional perspective.

Lastly, it is interesting to note that for the eleven included instruments, the mean score of items on the STARD was 12.4 (range: 2 to 18). It is important to emphasize that seven of the included instruments were published before the 2003 STARD criteria. Although, this mean score compared well to the mean scores of items on the STARD that were reported in test accuracy studies in reproductive medicine: 12.1, future research in this field will need to improve the reporting of the development of instruments that would assess healthcare professional's perspective of the decision-making process

Conclusion

This systematic review provides valuable data on instruments that assess the perception of physicians of the decision-making process within specific clinical encounters. It can be used by educators and health services researchers as a repository of standardized measures of the physician perspective of the clinical decision-making process and we hope of other healthcare providers. It was not our intention to identify the "best" instrument but rather to offer options to the target audience. We believe that based on the context of its intended use, a process of weighting its limitations and strengths and other factors faced by its potential users, most if not all of the identified instruments might play a valuable role in the future. This systematic review also sent an important signal: in the XXI century, the clinical decision-making process might only be adequately assessed by using a dyadic approach. In this regard, some of the identified instruments might be more attractive than others. However, more research is needed to investigate the validation of these instruments. More specifically, for the production of evidence on the validity and reliability data of the instruments, analytical methods that take into account within physician clustering is required. For all the included instruments, the development of corresponding patient versions should be encouraged. The combined use of the patient version with its respective healthcare professional version will help capture the complexity of the clinical decision-making process and thus of its dynamic and reciprocal nature. Only then will a new and more comprehensive understanding of health-related decision-making in the context of specific clinical encounters be possible.

References

McWhinney IR: A Textbook of Family Medicine. 1997, New York – Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2

Gale J, Marsden P: Diagnosis: Process not Product. Decision-making in General Practice. Edited by: Sheldon M, Brooke J, Rector A. 1985, New-York: Stockton Press, 59-90.

Chapman GB, Sonnenberg FA: Decision Making in Health Care. Theory, Psychology, and Applications. 2000, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Fish D, Coles C: Developing Professional Judgement in Health Care. Learning through the critical appreciation of practice. Butterworth-Heinemann. 1998

Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T: Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med. 1997, 44: 681-92. 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00221-3.

Elwyn G, Edwards A, Kinnersley P, Grol R: Shared decision making and the concept of equipoise: the competences of involving patients in healthcare choices. Br J Gen Pract. 2000, 50: 892-9.

Towle A, Godolphin W: Framework for teaching and learning informed shared decision making. BMJ. 1999, 319: 766-71.

Elwyn G, Edwards A, Kinnersley P: Shared decision-making in primary care: the neglected second half of the consultation. Br J Gen Pract. 1999, 49: 477-82.

Briss P, Rimer B, Reilley B, Coates RC, Lee NC, Mullen P, Corso P, Hutchinson AB, Hiatt R, Kerner J, George P, White C, Gandhi N, Saraiya M, Breslow R, Isham G, Teutsch SM, Hinman AR, Lawrence R: Promoting informed decisions about cancer screening in communities and healthcare systems. Am J Prev Med. 2004, 26: 67-80. 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.012.

Makoul G, Arntson P, Schofield T: Health promotion in primary care: physician-patient communication and decision making about prescription medications. Soc Sci Med. 1995, 41: 1241-54. 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00061-B.

Di Iorio CK: Measurement in health behavior. Methods for research and evaluation. 2005, San Francisco: Josey-Bass, 1

McDowell I, Newell C: Measuring Health. A guide to rating scales and questionnaires. 1987, New York: Oxford University Press, 2

Fawcett J: Conceptual Models and Theories. Analysis and Evaluation of Conceptual Models of Nursing. 1989, Philadelphia (PA): F.A. Davis Company, 1-40. 2

Streiner DL, Norman GR: Health Measurements Scales. A practical guide to their development and use. 1995, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Guyatt G, Walter S, Norman G: Measuring change over time: assessing the usefulness of evaluative instruments. J Chronic Dis. 1987, 40: 171-8. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90069-5.

Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB: The STARD initiative. Lancet. 2003, 361: 71-10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12122-8.

Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, Gatsonis CA, Glasziou PP, Irwig LM, Moher D, Rennie D, de Vet HC, Lijmer JG: The STARD statement for reporting studies of diagnostic accuracy: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2003, 138: W1-12.

Meyer GJ: Guidelines for reporting information in studies of diagnostic test accuracy: the STARD initiative. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2003, 81: 191-3. 10.1207/S15327752JPA8103_01.

Ashworth CD, Williamson P, Montano D: A scale to measure physician beliefs about psychosocial aspects of patient care. Soc Sci Med. 1984, 19: 1235-8. 10.1016/0277-9536(84)90376-9.

Baggs JG: Two instruments to measure interdisciplinary bioethical decision making. Heart Lung. 1993, 22: 542-7.

Bates AS, Harris LE, Tierney WM, Wolinsky FD: Dimensions and correlates of physician work satisfaction in a midwestern city. Med Care. 1998, 36: 610-17. 10.1097/00005650-199804000-00016.

de Monchy C, Richardson R, Brown R, Harden R: Measuring attitudes of doctors: the doctor-patient (DP) rating. Med Educ. 1988, 22: 231-9.

Garcia-Pena C, Reyes-Frausto S, Reyes-Lagunes I, Munoz Hernandez O: Family physician job satisfaction in different medical care organization models. Family Practice. 2000, 309-13. 10.1093/fampra/17.4.309.

Garcia-Pena C, Reyes-Lagunes I, Reyes-Frausto S, Villa-Contreras S, Libreros-Bango V, Munoz Hernandez O: Development and Validation of an Inventory for Measuring Job Satisfaction among Family Physicians. Psychological Reports. 1996, 79: 291-301.

Geller G, Tambor ES, Chase GA, Holtzman NA: Measuring physicians' tolerance for ambiguity and its relationship to their reported practices regarding genetic testing. Med Care. 1993, 31: 989-1001. 10.1097/00005650-199311000-00002.

Gerrity MS, DeVellis RF, Earp JA: Physicians' reactions to uncertainty in patient care. A new measure and new insights. Med Care. 1990, 28: 724-36. 10.1097/00005650-199008000-00005.

Gerrity MS, Earp JAL, De Vellis RF, Light DW: Uncertainty and Professional Work: Perceptions of Physicians in Clinical Practice. Am J Sociology. 1992, 97: 1022-51. 10.1086/229860.

Hojat M, Fields S, Veloski J, Griffiths M, Cohen M, Plumb J: Psychometric properties of an attitude scale measuring physician-nurse collaboration. Eval Health Prof. 1999, 22: 208-10.1177/01632789922034275.

Hojat M, Gonnella J, Nasca T, Fields S, Cicchetti A, Lo Scalzo A, Taroni F, Amicosante A, Macinati M, Tangucci M, Liva C, Ricciardi G, Eidelman S, Admi H, Geva H, Mashiach T, Alroy G, Alcorta-Gonzalez A, Ibarra D, Torres-Ruiz A: Comparisons of American, Israeli, Italian and Mexican physicians and nurses on the total and factor scores of the Jefferson scale of attitudes toward physician-nurse collaborative relationships. Int J Nurs Stud. 2003, 40: 427-35. 10.1016/S0020-7489(02)00108-6.

Hojat M, Gonnella J, Nasca T, Mangione S, Veloksi J, Magee M: The Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy: further psychometric data and differences by gender and specialty at item level. Acad Med. 2002, 77: S58-60. 10.1097/00001888-200210001-00019.

Hojat M, Nasca T, Cohen M, Fields S, Rattner S, Griffiths M, Ibarra D, de Gonzalez A, Torres-Ruiz A, Ibarra G, Garcia A: Attitudes toward physician-nurse collaboration: a cross-cultural study of male and female physicians and nurses in the United States and Mexico. Nurs res. 2001, 50: 123-8. 10.1097/00006199-200103000-00008.

Holtgrave DR, Lawler F, Spann SJ: Physicians' risk attitudes, laboratory usage, and referral decisions: the case of an academic family practice center. Med Decis Making. 1991, 11: 125-30. 10.1177/0272989X9101100210.

Konrad TR, Williams ES, Linzer M, McMurray J, Pathman DE, Gerrity M, Schwartz MD, Scheckler WE, Van Kirk J, Rhodes E, Douglas J: Measuring physician job satisfaction in a changing workplace and a challenging environment. SGIM Career Satisfaction Study Group. Society of General Internal Medicine. Med Care. 1999, 37: 1174-82. 10.1097/00005650-199911000-00010.

Krupat E, Rosenkranz SL, Yeager CM, Barnard K, Putman S, Inui TS: The practice orientations of physicians and patients: the effect of doctor-patient congruence on satisfaction. Patient Educ Couns. 2000, 39: 49-59. 10.1016/S0738-3991(99)00090-7.

Levinson W, Roter D: Physicians' psychosocial beliefs correlate with their patient communication skills. J Gen Intern Med. 1995, 10: 375-79. 10.1007/BF02599834.

Linn LS, DiMatteo MR, Cope DW, Robbins A: Measuring physicians' humanistic attitudes, values, and behaviors. Med Care. 1987, 25: 504-15. 10.1097/00005650-198706000-00005.

Linzer M, Konrad TR, Douglas J, McMurray JE, Pathman DE, Williams ES, Schwartz MD, Gerrity M, Scheckler W, Bigby JA, Rhodes E: Managed care, time pressure, and physician job satisfaction: results from the physician worklife study. J Gen Intern Med. 2000, 15: 441-50. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.05239.x.

Maheux C, Beaudoin C, Jean P, DesMarchais J, Cote L, M Tiraoui A: Development and validation of a measure of patient-centered care in medical practice. 1993

Markert RJ: Cross-cultural validation of the Doctor-Patient Scale. Acad Med. 1989, 64: 690-10.1097/00001888-198911000-00021.

Park HS, Lee SH, Shim JY, Cho JJ, Shin HC, Park JY: The physicians' recognition and attitude about patient education in practice. Journal of Korean Medical Science. 1996, 11: 422-28.

Pearson SD, Goldman L, Orav EJ, Guadagnoli E, Garcia TB, Johnson PA, Lee TH: Triage decisions for emergency department patients with chest pain: do physicians' risk attitudes make the difference?. J Gen Intern Med. 1995, 10: 557-64. 10.1007/BF02640365.

Scheckler WE, Schulz R, Moberg P: Physician satisfaction with the development of HMOs in Dane County: 1983–1993. Wis Med J. 1994, 93: 444-6.

Stiggelbout AM, Molewijk AC, Otten W, Timmermans DR, van Bockel JH, Kievit J: Ideals of patient autonomy in clinical decision making: a study on the development of a scale to assess patients' and physicians' views. J Med Ethics. 2004, 30: 268-74. 10.1136/jme.2003.003095.

Williams ES, Konrad TR, Linzer M, McMurray J, Pathman DE, Gerrity M, Schwartz MD, Scheckler WE, Van Kirk J, Rhodes E, Douglas J: Refining the measurement of physician job satisfaction: results from the Physician Worklife Survey. SGIM Career Satisfaction Study Group. Society of General Internal Medicine. Med Care. 1999, 37: 1140-54. 10.1097/00005650-199911000-00006.

Yildirim A, Akinci F, Ates M, Ross T, Issever H, Isci E, Selimen D: Turkish version of the Jefferson Scale of Attitudes Toward Physician-Nurse Collaboration: a preliminary study. Contemp Nurse. 2006, 23: 38-45.

Zandbelt LC, Smets EMA, Oort FJ, Godfried MH, de Haes HCJM: Satisfaction with the Outpatient Encounter: A Comparison of Patients' and Physicians' Views. J Gen Intern Med. 2004, 19: 1088-95. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30420.x.

Baggs JG, Ryan SA: ICU nurse-physician collaboration & nursing satisfaction. Nursing economic$. 1990, 8: 386-92.

Baggs JG, Schmitt MH: Intensive care decisions about level of aggressiveness of care. Res Nurs Health. 1995, 18: 345-55. 10.1002/nur.4770180408.

Baggs J: Psychometric evaluation of collaboration and satisfaction about care decision (CSACD) instrument. Heart & Lung. 1992, 21: 296-

Baggs JG: Development of an instrument to measure collaboration and satisfaction about care decisions. J Adv Nurs. 1994, 20: 176-82. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1994.20010176.x.

Baggs JG, Ryan SA, Phelps CE, Richeson JF, Johnson JE: The association between interdisciplinary collaboration and patient outcomes in a medical intensive care unit. Heart & Lung. 1992, 21: 18-24.

Baggs JG, Schmitt MH, Mushlin AI, Mitchell PH, Eldredge DH, Oakes D, Hutson AD: Association between nurse-physician collaboration and patient outcomes in three intensive care units. Critical Care Medicine. 1999, 27: 1991-98. 10.1097/00003246-199909000-00045.

Baggs JG, Schmitt MH, Mushlin AL, Eldredge DH, Oakes D, Hutson AD: Nurse-physician collaboration and satisfaction with the decision-making process in three critical care units. Am J Crit Care. 1997, 6: 393-99.

Barnett D, Bass P, Griffith C, Caudill S, Wilson J: Determinants of resident satisfaction with patients in their continuity clinic. J Gen Intern Med. 2004, 19: 456-59. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30125.x.

Bertram DA, Hershey CO, Opila DA, Quirin O: A measure of physician mental work load in internal medicine ambulatory care clinics. Med Care. 1990, 28: 458-67. 10.1097/00005650-199005000-00005.

Bertram DA, Opila DA, Brown JL, Gallagher SJ, Schifeling RW, Snow IS, Hershey CO: Measuring physician mental workload: reliability and validity assessment of a brief instrument. Med Care. 1992, 30: 95-104. 10.1097/00005650-199202000-00001.

Brothers TE, Cox MH, Robison JG: Prospective decision analysis modeling indicates that clinical decisions in vascular surgery often fail to maximize patient expected utility. J Surg Research. 2004, 120: 278-87. 10.1016/j.jss.2004.01.004.

Campbell C, Lockyer J, Laidlaw T, Macleod H: Assessment of a matched-pair instrument to examine doctor-patient communication skills in practising doctors. Med Educ. 2007, 41: 123-9. 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02657.x.

Carayon P, Hundt AS, Alvarado CJ, Springman SR, Ayoub P: Patient safety in outpatient surgery: the viewpoint of the healthcare providers. Ergonomics. 2006, 49: 470-85. 10.1080/00140130600568717.

Cegala D, McNeilis K, Socha McGee D, Jonas A: A study of doctor's and patient's perceptions of information processing and communication competence during the medical interview. Health Commun. 1995, 2: 179-203. 10.1207/s15327027hc0703_1.

Cegala DJ, Coleman MT, Turner JW: The development and partial assessment of the medical communication competence scale. Health Commun. 1998, 10: 261-88. 10.1207/s15327027hc1003_5.

Cegala DJ, Gade C, Lenzmeier Broz S, McClure L: Physicians' and Patients' Perceptions of Patients' Communication Competence in a Primary Care Medical Interview. Health Commun. 2004, 16: 289-304. 10.1207/S15327027HC1603_2.

Cegala DJ, Socha McGee D, McNeilis KS: Components of Patients' and Doctors' Perceptions of Communication Competence During a Primary Care Medical Interview. Health Commun. 1996, 8: 1-27. 10.1207/s15327027hc0801_1.

Dolan JG, Riggs AT, Gracey CF, Howard FM: Initial evaluation of the provider decision process assessment instrument (PDPAI): A process-based method for assessing the quality of health providers' decisions. Annual Meeting of the Society for Medical Decision Making: 1995: Med Dec Making;. 1995, 429-

Dolan JG: A method for evaluating health care providers' decision making: the Provider Decision Process Assessment Instrument. Med Decis Making. 1999, 19: 38-41. 10.1177/0272989X9901900105.

Gattellari M, Donnelly N, Taylor N, Meerkin M, Hirst G, Ward JE: Does 'peer coaching' increase GP capacity to promote informed decision making about PSA screening? A cluster randomised trial. Family Practice. 2005, 22: 253-65. 10.1093/fampra/cmi028.

Guimond P, Bunn H, O'Connor AM, Jacobsen MJ, Tait VK, Drake ER, Graham ID, Stacey D, Elmslie T: Validation of a tool to assess health practitioners' decision support and communication skills. Patient Educ Couns. 2003, 50: 235-45. 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00043-0.

Harmsen JA, Bernsen RM, Meeuwesen L, Pinto D, Bruijnzeels MA: Assessment of mutual understanding of physician patient encounters: development and validation of a Mutual Understanding Scale (MUS) in a multicultural general practice setting. Patient Educ Couns. 2005, 59: 171-81. 10.1016/j.pec.2004.11.003.

Légaré F, O'Connor AM, Graham ID, Wells GA, Tremblay S: Impact of the Ottawa Decision Support Framework on the agreement and the difference between patients' and physicians' decisional conflict. Med Decis Making. 2006, 26: 373-90. 10.1177/0272989X06290492.

Légaré F, O'Connor A, Graham I, Wells G, Jacobsen MJ, Elmslie T, Drake E: The effect of decision aids on the agreement between women's and physician's decisional conflict about hormone replacement therapy. Patient Educ Couns. 2003, 50: 211-21. 10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00129-5.

Légaré F, Tremblay S, O'Connor AM, Graham ID, Wells GA, Jacobsen MJ: Factors associated with the difference in score between women's and doctors' decisional conflict about hormone therapy: a multilevel regression analysis. Health Expect. 2003, 6: 208-21. 10.1046/j.1369-6513.2003.00234.x.

Levinson W, Stiles WB, Inui TS, Engle R: Physician frustration in communicating with patients. Med Care. 1993, 31: 285-95. 10.1097/00005650-199304000-00001.

Linden M, Pyrkosch L, Dittmann RFW, Czekalla J: Why do physicians switch from one antipsychotic agent to another? – The "Physician drug stereotype". Journal of clinical psychopharmacology. 2006, 26: 225-31. 10.1097/01.jcp.0000219917.88810.55.

Margalit AP, Glick SM, Benbassat J, Cohen A, Katz M: Promoting a biopsychosocial orientation in family practice: effect of two teaching programs on the knowledge and attitudes of practising primary care physicians. Medical Teacher. 2005, 27: 613-18. 10.1080/01421590500097091.

Moore-Smithson J: The association between nurse-physician collaboration and satisfaction with the decision-making process in the ambulatory care setting. 2005, M.S. United States – New York: D'Youville College

Newes-Adeyi G, Helitzer DL, Roter D, Caulfield LE: Improving client-provider communication: evaluation of a training program for women, infants and children (WIC) professionals in New York state. Patient Educ Couns. 2004, 55: 210-7. 10.1016/j.pec.2003.05.001.

Dobkin PL, De Civita M, Abrahamowicz M, Bernatsky S, Schulz J, Sewitch M, Baron M: Patient-physician discordance in fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2003, 30: 1326-34.

Dobkin PL, Sita A, Sewitch MJ: Predictors of adherence to treatment in women with fibromyalgia. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2006, 22: 286-94. 10.1097/01.ajp.0000173016.87612.4b.

Sewitch M: Effect of discordant physician-patient perceptions on patient adherence in inflammatory bowel disease. Doctoral Dissertation. 2001, Montreal: McGill University

Sewitch MJ, Abrahamowicz M, Barkun A, Bitton A, Wild GE, Cohen A, Dobkin PL: Patient nonadherence to medication in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003, 98: 1535-44. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07522.x.

Sewitch MJ, Abrahamowicz M, Dobkin PL, Tamblyn R: Measuring differences between patients' and physicians' health perceptions: the patient-physician discordance scale. J Behav Med. 2003, 26: 245-64. 10.1023/A:1023412604715.

Sewitch MJ, Dobkin PL, Bernatsky S, Baron M, Starr M, Cohen M, Fitzcharles MA: Medication non-adherence in women with fibromyalgia. Rheumatology. 2004, 43: 648-54. 10.1093/rheumatology/keh141.

Shore BE, Franks P: Physician satisfaction with patient encounters. Reliability and validity of an encounter-specific questionnaire. Med Care. 1986, 24: 580-9. 10.1097/00005650-198607000-00002.

Suchman AL, Roter D, Green M, Lipkin M: Physician satisfaction with primary care office visits. Collaborative Study Group of the American Academy on Physician and Patient. Med Care. 1993, 31: 1083-92. 10.1097/00005650-199312000-00002.

Sullivan MD, Leigh J, Gaster B: Brief report: Training internists in shared decision making about chronic opioid treatment for noncancer pain. J Gen Intern Med. 2006, 21: 360-2. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00352.x.

Hakkennes S, Green S: Measures for assessing practice change in medical practitioners. Implement Sci. 2006, 1: 29-10.1186/1748-5908-1-29.

Grol R, Leatherman S: Improving quality in British primary care: seeking the right balance. Br J Gen Pract. 2002, 52 (Suppl): S3-4.

Grol R, Grimshaw J: From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients' care. Lancet. 2003, 362: 1225-30. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14546-1.

Eccles M, Grimshaw J, Walker A, Johnston M, Pitts N: Changing the behavior of healthcare professionals: the use of theory in promoting the uptake of research findings. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005, 58: 107-12. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.09.002.

Hardeman W, Johnston M, Johnston DW, Bonetti D, Wareham NJ, Kinmonth AL: Application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour in Behaviour Change Interventions: a Systematic Review. Psychology and Health. 2002, 17: 123-58.

Kashy DA, Kenny DA: The analysis of data from dyads and groups. Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology. Edited by: Reis HT, Judd CM. 2000, New York: Cambridge University Press, 451-77.

Kenny DA, Cook W: Partner effects in relationship research: Conceptual issues, analytic difficulties, and illustrations. Personal Relationships. 1999, 6: 433-48. 10.1111/j.1475-6811.1999.tb00202.x.

Suchman AL: A new theoretical foundation for relationship-centered care. Complex responsive processes of relating. J Gen Intern Med. 2006, 21: S40-4. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00308.x.

Jepson C, Asch DA, Hershey JC, Ubel PA: In a mailed physician survey, questionnaire length had a threshold effect on response rate. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005, 58: 103-5. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.06.004.

Elwyn G, Edwards A, Mowle S, Wensing M, Wilkinson C, Kinnersley P, Grol R: Measuring the involvement of patients in shared decision-making: a systematic review of instruments. Patient Educ Couns. 2001, 43: 5-22. 10.1016/S0738-3991(00)00149-X.

Curran VR, Deacon DR, Fleet L: Academic administrators' attitudes towards interprofessional education in Canadian schools of health professional education. J Interprof Care. 2005, 19 (Suppl 1): 76-86. 10.1080/13561820500081802.

Gravel K, Legare F, Graham ID: Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: A systematic review of health professionals' perceptions. Implement Sci. 2006, 1: 16-10.1186/1748-5908-1-16.

Stewart M, Belle Brown J, Weston W, McWhinney IR, McMillan CL, Freeman TR: Patient-Centered Medicine. Transforming the Clinical Method. 1995, London: Sage Publications

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6947/7/30/prepub

Acknowledgements

We thank all the authors who were contacted and who provided us with assistance. We also thank M. Marc-André Morin, a student in psychology, who contributed to an earlier draft of the protocol and first identification of eligible instruments. We acknowledge the contribution of Margaret Sampson, Alexandra Davis and Stéphane Ratté for helping to design, update and run the search strategy. Dr. Légaré is supported by a Canada Research Chair in Implementation of Shared Decision Making in Primary Care, Université Laval and CanGenetest. Dr. Moher is supported by a University of Ottawa Research Chair.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

All author(s) declare that they have no conflicting financial interests.

One of the authors (FL) is an author of three of the included studies.

Authors' contributions

FL conceived the study, supervised KG and AL, validated the methods, validated the article selection, abstracted all included instruments, analysed the results, and wrote the paper. KG participated in the selection of the articles and abstracted all included instruments. KG and AL assessed the quality of the included studies and reviewed the paper. DM participated in the conception of the review, provided comments on the search strategy, validated the methods and reviewed the paper. GE validated the methods, participated in the interpretation of the results and reviewed the paper. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript. FL is its guarantor.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Légaré, F., Moher, D., Elwyn, G. et al. Instruments to assess the perception of physicians in the decision-making process of specific clinical encounters: a systematic review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 7, 30 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-7-30

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-7-30