Abstract

Background

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) has frequently been used to treat tinnitus, and acupuncture is a particularly popular option. The objective of this review was to assess the evidence concerning the effectiveness of acupuncture as a treatment for tinnitus.

Methods

Fourteen databases were searched from the dates of their creation to July 4th, 2012. Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) were included if acupuncture was used as the sole treatment. The Cochrane risk of bias tool was used to assess the risk of bias.

Results

A total of 9 RCTs met all the inclusion criteria. Their methodological quality was mostly poor. Five RCTs compared the effectiveness of acupuncture or electroacupuncture with sham acupuncture for treating tinnitus. The results failed to show statistically significant improvements. Two RCTs compared a short one-time scalp acupuncture treatment with the use of penetrating sham acupuncture at non-acupoints in achieving subjective symptom relief on a visual analog scale; these RCTs demonstrated significant positive effects with scalp acupuncture. Two RCTs compared acupuncture with conventional drug treatments. One of these RCTs demonstrated that acupuncture had statistically significant effects on the response rate in patients with nervous tinnitus, but the other RCT did not demonstrate significant effects in patients with senile tinnitus.

Conclusions

The number, size and quality of the RCTs on the effectiveness of acupuncture for the treatment of tinnitus are not sufficient for drawing definitive conclusions. Further rigorous RCTs that overcome the many limitations of the current evidence are warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Tinnitus is a common yet poorly understood disorder [1]. It is defined as the perception of sounds for which there is no external acoustic source [2]. Tinnitus is often associated with sudden, temporary hearing loss, and it can have a powerful detrimental impact on a patient’s quality of life. Tinnitus may result in sleep disturbances, work impairments and distress [3]. Approximately 10-15% of the general population experiences a persistent sensation of tinnitus. Tinnitus occurs most commonly among the elderly, but it can occur at any age. In many patients, the emergence of tinnitus occurs long after the disappearance of the underlying medical condition [2, 4]. The pathophysiological mechanism of tinnitus is still unclear, and the disease is difficult to treat effectively [5]. There is firm clinical evidence that cognitive behavioral therapy, which is a type of psychotherapy, improves the quality of life of tinnitus patients [6]. However, no other therapies, including pharmacological treatment, can be considered to have well-established effectiveness in reducing tinnitus symptoms and the related quality of life [7–9].

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) has frequently been used to treat tinnitus, and acupuncture is a particularly popular option. Acupuncture is a therapeutic technique involving the insertion and manipulation of needles in the body. The use of acupuncture for treating the symptoms of tinnitus is similar to its use for pain relief because both conditions produce disagreeable sensory and emotional experiences [10]. The rationale for the use of acupuncture is the principle that a needle stimulus may elicit an electrical charge that triggers action potentials to rebalance the neurophysiological system or the function of the olivocochlear nucleus [11, 12]. In the theory of traditional Asian medicine, tinnitus is closely connected to the yin-yang imbalance of the kidneys and of other internal organs such as the gallbladder because channels originating from these organs flow through the ear. Acupuncture is considered to be able to balance this skewed condition [13]. Several studies have reported that acupuncture can generate immediate relief from both the loudness and the disturbing quality of tinnitus, thereby resulting in a significant improvement in the quality of life [14, 15]. Other studies have failed to show the effectiveness of the approach [16–18].

Dobie [7] summarized the clinical effectiveness of various alternative therapies, including acupuncture, in treating tinnitus. One systematic review published 12 years ago reported that the 6 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) cited did not produce convincingly positive effects [19]. However, these reviews did not perform systematic assessments [7] or are out of date [19].

The aim of this systematic review was to critically evaluate the current evidence from RCTs on the use of acupuncture as a symptomatic treatment for patients with tinnitus.

Methods

Data sources

The following databases were searched from their dates of creation through July 4th, 2012: MEDLINE, AMED, EMBASE, CINAHL, five Korean medical databases (Korean Studies Information, DBPIA, Korea Institute of Science and Technology Information, KoreaMed and the Research Information Service System), four Chinese medical databases (China National Knowledge Infrastructure databases: Chinese Academic Journals, the Century Journal Project, the China Doctoral/Master Dissertation full text database and the China Conference Proceedings full text database) and the Cochrane Library (2012, Issue 4). Two sets of search terms were used. The first set included terms for acupuncture, and the second set included terms for tinnitus (Additional file 1). The two sets were combined using the Boolean operator AND. The term ’acupuncture’ would also capture manual acupuncture, electroacupuncture (EA), scalp acupuncture and auricular acupuncture therapy. The Korean and Chinese terms for acupuncture and tinnitus were used in the Korean and Chinese databases. We also performed electronic searches of the relevant journals (Focus on Alternative and Complementary Therapies and Forschende Komplementarmedizin) through June 2012. Additionally, the reference lists of all the papers obtained were searched. Furthermore, our own personal files were manually searched. Hardcopies of all articles were obtained and read in full.

Study selection

Types of studies

All prospective RCTs and quasi-RCTs were included in this review. Trials in which acupuncture was performed as part of a complex intervention were excluded. We excluded case studies, case series, qualitative studies, uncontrolled studies and controlled trials without randomization methods. Trials published in the form of dissertations and abstracts were included. No language restrictions were imposed.

Types of participants

Studies of patients of both sexes and any age with any type of tinnitus were included.

Types of interventions

Studies investigating the use of any type of needle acupuncture, with or without electrical stimulation, in tinnitus patients were included. We also included studies that examined the use of auricular acupuncture and scalp acupuncture in tinnitus patients. Trials with acupuncture as a concomitant treatment with other types of complementary therapies were excluded.

Types of controls

We included studies with control groups that received no treatment, sham acupuncture (i.e., penetrating insertion of a needle at a point other than a valid acupuncture point (a non-acupoint), superficial insertion at an acupuncture point or non-penetrating acupuncture at an acupuncture point or a non-acupoint) and relevant conventional drug therapies for tinnitus. Trials with designs that did not allow for the evaluation of the efficacy of the acupuncture (e.g., using other types of complementary therapies in the control group or comparing two forms of acupuncture or electroacupuncture) were excluded.

Types of outcome measures

Studies were required to include either the symptom severity or the relief of symptoms in tinnitus as outcome measures. Other clinically important outcomes included the quality of life, the response rate (i.e., responder vs. non-responder) and adverse events.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Hard copies of all articles that appeared promising based on their abstract were obtained and read in full. All articles were read by three independent reviewers (JIK, MSL, and TYC), and data from the articles were validated and extracted according to pre-defined criteria (Table 1).

The risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane classification of seven criteria: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, patient blinding, assessor blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other risks of bias [24]. Because it is difficult to blind therapists to the use of acupuncture, we assessed patient and assessor blinding separately. We assigned low risk of bias for assessor blinding if the tinnitus was assessed by someone other than the therapist or the patient who did not know the group assignments. Disagreements were resolved by discussion between the three reviewers (JIK, MSL, and TYC).

Results

Study description

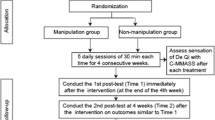

The literature searches revealed 382 articles, of which 373 studies were excluded (Figure 1). Of these excluded studies, the reasons for the 14 excluded RCTs were as follows.

Five studies employed mixed interventions that included acupuncture in the active treatment group, including electroacupuncture plus herbal medicine injection [25], acupuncture plus gua-sha and cupping [26], acupuncture plus mixed administration of herbal and conventional medicines [27] and acupuncture plus herbal medicine ingestion [28, 29]. Nine studies employed interventions of unproven efficacy in the control group, including another type of acupuncture [30–36], physiotherapy [37], and biofeedback in one control group and a third control medication in another group [38].

Nine RCTs met our inclusion criteria, and their key data are listed in Table 1[12, 15–18, 20–23]. Three of the included RCTs were from Denmark [16, 18, 21], two were from China [22, 23], two were from Brazil [12, 15], one was from England [17], and one was from Korea [20]. Five of the included trials adopted a two-armed parallel group design [12, 15, 18, 20, 23], two used a three-armed parallel group design [21, 22], and two RCTs employed a crossover design [16, 17]. Five trials employed manual acupuncture [16, 18, 20, 22, 23], one used electroacupuncture [17], one used manual acupuncture and EA [21], and two used scalp needle acupuncture [12, 15]. The number of treatment sessions ranged from one to 30 sessions lasting from 15 seconds to 30 minutes each. The acupuncture points were selected according to traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) theory in eight RCTs [12, 15–18, 21–23] and protocol of previous study in one RCT [20] (Table 2).

Risk of bias

Four RCTs employed adequate methods of random sequence generation [12, 15, 20, 23]. Two RCTs had a low risk of bias [20, 23], but the risk of bias in the sequence generation was high in 2 RCTs [12, 15]. One RCT employed allocation concealment [16]. Six of the 8 RCTs adopted both assessor and subject blinding [12, 15–18, 20], and another RCT adopted only assessor blinding [21]. Three RCTs had a low risk of bias due to incomplete outcome data criteria [16, 20, 21]. The risk of bias in selective outcome reporting was low in three RCTs [20–22] and high in one RCT [23] (Table 3).

Outcomes

Acupuncture vs. sham acupuncture

Seven RCTs tested the effectiveness of several types of acupuncture on symptoms of tinnitus comparing with penetrating or non-penetrating acupunctures [12, 15–18, 20, 21].

Among them, five RCTs compared manual acupuncture or electroacupuncture on the symptoms of tinnitus to penetrating or non-penetrating acupuncture on acupoints [16–18, 20, 21]. The results failed to demonstrate statistically significant improvements in the periodic index, annoyance, loudness, awareness, Tinnitus Handicap Inventory, symptoms in visual analogue scale and response rate, although differences were found in some of subjective general evaluation of the treatment.

Two RCTs compared the effectiveness of a short one-time scalp acupuncture treatment to penetrating sham acupuncture at non-acupoints in achieving subjective symptom relief on a visual analog scale and in reducing the amplitude of otoacoustic emissions (OAE) [12, 15]. One of these trials demonstrated significant effects of scalp acupuncture on symptom relief [12, 15], but the other trial failed to significantly reduce OAE [12, 15].

Acupuncture vs. conventional drug therapy

Two RCTs compared acupuncture with conventional drug treatments, including Bandazol and Flunarizine hydrochloride [22, 23]. One of these trials suggested that acupuncture had positive effects on the response rate in patients with nervous tinnitus [22], but the other trial failed to demonstrate improvement in patients with senile tinnitus [23].

Discussion

Few sham-controlled RCTs have tested the effectiveness of acupuncture on tinnitus. Collectively, the results of the existing studies have failed to demonstrate specific effects of acupuncture. Only two of the 7 sham-controlled RCTs suggested positive effects. These two RCTs demonstrated beneficial effects of acupuncture for tinnitus when acupuncture was compared with drug therapy. However, the studies were too small to generate reliable findings. Both of the trials had small sample sizes [n < 40 for each group] and were thus prone to a type II error or an exaggeration of the treatment effect [39, 40]. Overall, our findings provided no convincing evidence that acupuncture is beneficial for treating tinnitus.

We identified 6 new RCTs that had not been examined in previous reviews [12, 15, 20–23]. Nevertheless, the results of our review are similar to those of a previous review [19] that showed that acupuncture was not supported by sound evidence as a treatment for tinnitus. The previous review expressed concern regarding the poor methodological quality of the primary studies included.

Although most of the RCTs included in the present review employed sham-control groups, none was flawless. Five RCTs included fewer than 10 sessions [15–17, 21, 22], which may be insufficient for obtaining a positive clinical outcome. Two trials provided acupuncture in only a single session [15, 22]. The likelihood of an inherent bias in the studies was assessed based on the description of the methods of randomization, blinding, and allocation concealment. Most of the included trials had a high risk of bias. Low-quality trials are more likely to overestimate the effect size [41, 42]. None of the studies used a power calculation, and the sample sizes were usually small. Details regarding the dropouts and withdrawals were described in three trials [16, 20, 21]. However, the other RCTs did not report this information, which can lead to an exclusion or attrition bias. Consequently, the reliability of the evidence presented here is clearly limited.

Several sham acupuncture methods have been proposed for acupuncture trials. These methods include the penetrating insertion of needles at non-acupoints [12, 15, 16], superficially puncturing the skin at non-acupoints [18, 20, 21], and the non-penetration of non-acupoints [17]. In the present systematic review, no evidence for the superiority of real acupuncture over sham acupuncture was found, regardless of the acupuncture technique employed. Non-penetrating sham acupuncture has been reported to be superior to placebo tablets in reducing subjective pain [43]. This finding may suggest that most of the effects of needle acupuncture are nonspecific in nature.

Two RCTs from China compared acupuncture with conventional drug treatment and demonstrated positive effects on at least one outcome. However, the current evidence for the effectiveness of these drug therapies for treating tinnitus is not clear, and some drug therapies have been shown to be less effective than other forms of therapy. Additionally, the risk of bias in these RCTs was high, and the findings may be overestimated. Consequently, the evidence comparing acupuncture with drug therapies for the treatment of tinnitus is not clear.

Two RCTs compared the efficacy of scalp acupuncture with sham acupuncture for treating tinnitus[12, 15]. Although the results demonstrated significant benefits from the scalp acupuncture, these trials also had a high risk of bias in randomization and allocation concealment. Consequently, these trials are likely to have overestimated the effect size.

The rationale for the acupuncture point selection was stated in all of the included RCTs. The authors in eight of the included RCTs quoted traditional Chinese theory as the justification for their point selection and used acupoints from the previous study in one RCT [20]. Needle stimulation resulting in the desired sensation (de-qi) in the patient is considered to be important for achieving maximal effects. This needle sensation was considered in the six RCTs included [16–18, 20–22]. In the present data set, we found no evidence that the presence or absence of de-qi exerted an important influence on the clinical outcome.

Most of the included RCTs adopted questionnaires or self-reported inventories concerning the symptoms related to tinnitus. However, it is important to use only validated questionnaires. Unless the reliability and validity of the outcome measures used have been established, the data derived from the measures are subject to bias, and comparisons between the results of different studies are difficult.

In the included studies, several types of active acupuncture treatment were used: five RCTs used traditional manual body acupuncture [16, 18, 20, 22, 23]; one RCT used electroacupuncture [17]; one RCT used both manual body acupuncture and electroacupuncture [21]; and two RCTs used scalp acupuncture [12, 15]. For all of these different types of needle stimulation, de-qi (i.e., sensation of needling in both practitioners and patients) might be a very important therapeutic factor in both traditional Asian medical viewpoint and neurophysiology [29]. However, the underlying neurophysiologic mechanism of these different acupuncture types according to the stimulating region (body versus scalp) and/or stimulating methods (manual versus electrical stimulation), might not be the same [44–46]. Therefore, the effect of different type of acupuncture on tinnitus should be interpreted apart and cannot be simply pooled altogether in future meta-analysis.

The experience and the number of the acupuncture practitioners used can influence the results of acupuncture clinical trials. Of the included trials, one trial [21] reported that one acupuncturist with more than 10 years of experience administered all of the treatments of real and sham acupuncture. No information was reported regarding the acupuncture practitioners in the other trials; consequently, we do not know whether the acupuncture was administered by well-trained practitioners.

Reports of adverse events from acupuncture are scarce, and those that have been reported are mild [47, 48]. Adverse effects from acupuncture were reported in one of the reviewed RCTs [15]. Two cases of significant pain from the needles were reported. The fact that several RCTs did not clearly mention adverse effects demonstrates the poor reporting standards of acupuncture research.

Our review has a number of important limitations. Although substantial efforts were made to retrieve all RCTs on the subject, we cannot be certain that our search was exhaustive. Moreover, selective publishing and reporting are major causes of bias that should be considered [49–51]. It is conceivable that several negative RCTs remain unpublished, and this may distort the overall understanding of acupuncture. Further limitations include the paucity and the often-suboptimal methodological quality of the primary data. These factors influence both the quality and the quantity of the research reviewed. In total, these factors limit the conclusiveness of this systematic review.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the evidence from sham-controlled RCTs testing the effectiveness of acupuncture for the treatment of tinnitus is not yet convincing. The number, size and quality of the RCTs are not sufficient for drawing definitive conclusions. Further rigorous RCTs that overcome the many limitations of the current evidence are warranted. However, in clinical practice, acupuncture treatment by experienced and licensed practitioners might be an option for tinnitus patients, especially when the patients refuse psychological behavioral therapy, which is the only treatment with clinical evidence demonstrating improved quality of life in tinnitus patients. Additionally, because acupuncture is a safe procedure and because there is no current treatment for which clinical efficacy has been demonstrated for specific tinnitus symptoms, acupuncture is an option for the treatment of tinnitus symptoms in patients who request this procedure in the clinic.

References

Lockwood AH, Salvi RJ, Burkard RF: Tinnitus. N Engl J Med. 2002, 347 (12): 904-910. 10.1056/NEJMra013395.

Henry JA, Dennis KC, Schechter MA: General review of tinnitus: prevalence, mechanisms, effects, and management. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2005, 48 (5): 1204-1235. 10.1044/1092-4388(2005/084).

Dobie RA: Depression and tinnitus. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2003, 36 (2): 383-388. 10.1016/S0030-6665(02)00168-8.

Heller AJ: Classification and epidemiology of tinnitus. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2003, 36 (2): 239-248. 10.1016/S0030-6665(02)00160-3.

Ahmad N, Seidman M: Tinnitus in the older adult: epidemiology, pathophysiology and treatment options. Drugs Aging. 2004, 21 (5): 297-305. 10.2165/00002512-200421050-00002.

Savage J, Waddell A: Tinnitus. Clin Evid. 2012, 2: 506-

Dobie RA: A review of randomized clinical trials in tinnitus. Laryngoscope. 1999, 109 (8): 1202-1211. 10.1097/00005537-199908000-00004.

Langguth B, Salvi R, Elgoyhen AB: Emerging pharmacotherapy of tinnitus. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2009, 14 (4): 687-702. 10.1517/14728210903206975.

Lockwood AH: Tinnitus. Neurol Clin. 2005, 23 (3): 893-900. 10.1016/j.ncl.2005.01.007. viii

Chami F: A utilização da acupuntura em pacientes portadores de zumbido. Zumbido: Avaliação, Diagnóstico e Reabilitação - Abordagens atuais. 2004, Lovise, São Paulo

Kiyoshita Y: Acupuncture treatment of tinnitus: evaluation of its efficacy by objective methods. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990, 62: 351-357.

de Azevedo RF, Cbiari BM, Okada DM, Onisbi ET: Impact of acupuncture on otoacoustic emissions in patients with tinnitus. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2007, 73 (5): 599-607.

Maciocia G: The practice of Chinese medicine : the treatment of diseases with acupuncture and Chinese herbs. 2008, Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, 2

Axelsson A, Andersson S, Gu LD: Acupuncture in the management of tinnitus: a placebo-controlled study. Audiology. 1994, 33 (6): 351-360. 10.3109/00206099409071892.

Okada DM, Onishi ET, Chami FI, Borin A, Cassola N, Guerreiro VM: Acupuncture for tinnitus immediate relief. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2006, 72 (2): 182-186.

Hansen PE, Hansen JH, Bentzen O: Acupuncture treatment of chronic unilateral tinnitus–a double-blind cross-over trial. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1982, 7 (5): 325-329. 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1982.tb01914.x.

Marks NJ, Emery P, Onisiphorou C: A controlled trial of acupuncture in tinnitus. J Laryngol Otol. 1984, 98 (11): 1103-1109. 10.1017/S0022215100148091.

Vilholm OJ, Moller K, Jorgensen K: Effect of traditional Chinese acupuncture on severe tinnitus: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical investigation with open therapeutic control. Br J Audiol. 1998, 32 (3): 197-204. 10.3109/03005364000000063.

Park J, White AR, Ernst E: Efficacy of acupuncture as a treatment for tinnitus: a systematic review. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000, 126 (4): 489-492.

Jeon SW, Kim KS, Nam HJ: Long-Term Effect of Acupuncture for Treatment of Tinnitus: A Randomized, Patient- and Assessor-Blind, Sham-Acupuncture-Controlled, Pilot Trial. Journal of alternative and complementary medicine (New York, NY). 2012, 18 (7): 693-699. 10.1089/acm.2011.0378.

Wang K, Bugge J, Bugge S: A randomised, placebo-controlled trial of manual and electrical acupuncture for the treatment of tinnitus. Complement Ther Med. 2010, 18 (6): 249-255. 10.1016/j.ctim.2010.09.005.

Tan KQ, Zhang C, Liu MX, Qiu L: Comparative study on therapeutic effects of acupuncture, Chinese herbs and western medicine on nervous tinnitus. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2007, 27 (4): 249-250.

Jiang B, Jiang ZL, Wang L, Li RM: Acupuncture treatment for senile of tinnitus of 30 cases. Jiangsu J TCM. 2010, 42 (6): 52-53.

Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC: Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 510 (updated March 2011). Edited by: Higgins JPT, Green S. 2011, The Cochrane Collaboration, Available from wwwcochrane-handbookorg

Liu KQ, Zhou SH, Zu TY: Acupuncture andherbal medicine treatment of 132 cases of intractable tinnitus. Jiangxi J Tradit Chin Med. 2007, 56 (10):

Fan HM, Zhou J, Shen QH: Gua Sha plus cupping and acupuncture treatment of menopausal women, 24 cases of tinnitus. Tradit Chin Med Res. 2006, 19 (5): 31-32.

Xia H, Xiao SJ: Combination of Chinese and Western medicine treatment of 50 cases of tinnitus. Acta Academiae Medicinae Jiangxi. 2004, 44 (1): 137-

Zheng CC: Acupuncture Treatment of Kidney essence a loss of type sensorineural hearing loss with tinnitus and the effect of observation. Jiangxi J Tradit Chin Med. 2004, 10: 56-

Hui KK, Nixon EE, Vangel MG, Liu J, Marina O, Napadow V, Hodge SM, Rosen BR, Makris N, Kennedy DN: Characterization of the “deqi” response in acupuncture. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2007, 7: 33-10.1186/1472-6882-7-33.

Liu JZ, Ju YL, OuYang DL: Electro-acupuncture treatment with the super laser irradiation sensorineural deafness clinical study of tinnitus. J Tradit Chin Med Univ Hunan. 2006, 26 (2): 48-49.

Ai BW, Guo YF, Luo M: Irradiation plus acupuncture treatment for tinnitus of nerve in 32 cases. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2006, 26 (6): 406-

Li J, Fang XL: Clinical observation on warming-removing obstruction needling method for treatment of sudden tinnitus and deafness. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2008, 28 (5): 353-355.

Li W, Tan L, Li PM, Gao XQ: Irradiation acupoint acupuncture treatment efficacy of nerve tinnitus. J Clin Acupunct Moxibustion. 2007, 23 (9): 39-40.

Wang B, Liu JY: Electro-acupuncture treatment of neurogenic tinnitus and deafness in 70 cases. Chin J Information on Tradit Chin Med. 2005, 12 (3): 68-69.

Zhang Q, Zhang BY, Wang ZH: Auricular acupuncture treatment plus injection of 82 cases of neurogenic tinnitus. J Clin Acupunct Moxibustion. 2007, 23 (4): 34-

Zhou ZT, Lin XS, ZHou MQ: Abdominal acupuncture for treatment of 42 cases of sudden deafness. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2006, 4

Furugard S, Hedin PJ, Eggertz A, Laurent C: Acupuncture worth trying in severe tinnitus. Lakartidningen. 1998, 95 (17): 1922-1928.

Podoshin L, Ben-David Y, Fradis M, Gerstel R, Felner H: Idiopathic subjective tinnitus treated by biofeedback, acupuncture and drug therapy. Ear Nose Throat J. 1991, 70 (5): 284-289.

Moore A, Edwards J, Barden J, McQuay H: Bandolier’s Little Book of Pain. 2003, Oxford University Press, Oxford, New York

Moore A, McQuay H: Bandolier’s Little Book of Making Sense of the Medical Evidence. 2006, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

Day SJ, Altman DG: Statistics notes: blinding in clinical trials and other studies. BMJ. 2000, 321 (7259): 504-10.1136/bmj.321.7259.504.

Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman DG: Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA. 1995, 273 (5): 408-412. 10.1001/jama.1995.03520290060030.

Kaptchuk TJ, Stason WB, Davis RB, Legedza AR, Schnyer RN, Kerr CE, Stone DA, Nam BH, Kirsch I, Goldman RH: Sham device v inert pill: randomised controlled trial of two placebo treatments. BMJ. 2006, 332 (7538): 391-397. 10.1136/bmj.38726.603310.55.

Park SU, Shin AS, Jahng GH, Moon SK, Park JM: Effects of scalp acupuncture versus upper and lower limb acupuncture on signal activation of blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) fMRI of the brain and somatosensory cortex. Journal of alternative and complementary medicine (New York, NY). 2009, 15 (11): 1193-1200. 10.1089/acm.2008.0602.

Yamamoto H, Kawada T, Kamiya A, Miyazaki S, Sugimachi M: Involvement of the mechanoreceptors in the sensory mechanisms of manual and electrical acupuncture. Auton Neurosci. 2011, 160 (1–2): 27-31.

Liu Z, Guan L, Wang Y, Xie CL, Lin XM, Zheng GQ: History and mechanism for treatment of intracerebral hemorrhage with scalp acupuncture. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012, 2012: 895032-

Melchart D, Weidenhammer W, Streng A, Reitmayr S, Hoppe A, Ernst E, Linde K: Prospective investigation of adverse effects of acupuncture in 97 733 patients. Arch Intern Med. 2004, 164 (1): 104-105. 10.1001/archinte.164.1.104.

White A, Hayhoe S, Hart A, Ernst E: Adverse events following acupuncture: prospective survey of 32 000 consultations with doctors and physiotherapists. BMJ. 2001, 323 (7311): 485-486. 10.1136/bmj.323.7311.485.

Ernst E: Publication bias in complementary/alternative medicine. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007, 60 (11): 1093-1094. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.07.002.

Ernst E, Pittler MH: Alternative therapy bias. Nature. 1997, 385 (6616): 480-

Rothstein HR, Sutton AJ, Borenstein M: Publication bias in meta-analysis. Publication bias in meta-analysis. Edited by: Rothstein HR, Sutton AJ, Chichester BM. 2005, West Sussex, Wiley

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6882/12/97/prepub

Acknowledgement

MS Lee and TYC were supported by KIOM (C12080 and K11111).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Authors’ contributions

JIK, JYC, TYC and MSL designed the review, performed searches, appraised and selected trials, extracted data, contacted authors for additional data, carried out analyses and interpretations of the data, and drafted this report. DHL and EE reviewed and critiqued this review and report and assisted with interpretation of the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Jong-In Kim, Jun-Yong Choi contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, JI., Choi, JY., Lee, DH. et al. Acupuncture for the treatment of tinnitus: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. BMC Complement Altern Med 12, 97 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-12-97

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-12-97