Abstract

Background

Drug resistance in bacteria has become a global concern and the search for new antibacterial agents is urgent and ongoing. Endophytes provide an abundant reservoir of bioactive metabolites for medicinal exploitation, and an increasing number of novel compounds are being isolated from endophytic fungi. Ophiopogon japonicus, containing compounds with antibacterial activity, is a traditional Chinese medicinal plant used for eliminating phlegm, relieving coughs, latent heat in the lungs, and alleviating diabetes mellitus. We investigated the antimicrobial activities of 30 strains of O. japonicus.

Methods

Fungal endophytes were isolated from roots and stems of O. japonicus collected from Chongqing City, southwestern China. Mycelial extracts (MC) and fermentation broth (FB) were tested for antimicrobial activity using peptide deformylase (PDF) inhibition fluorescence assays and MTT cell proliferation assays.

Results

A total of 30 endophytic strains were isolated from O. japonicus; 22 from roots and eight from stems. 53.33% of the mycelial extracts (MC) and 33.33% of the fermentation broths (FB) displayed potent inhibition of PDF. 80% of MC and 33.33% of FB significantly inhibited Staphylococcus aureus. 70% of MC and 36.67% of FB showed strong activities against Cryptococcus neoformans. None showed influence on Escherichia coli.

Conclusion

The secondary metabolites of endophytic fungi from O. japonicus are potential antimicrobial agents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Endophytes are microorganisms that live in the intercellular spaces of healthy host tissues without causing obvious symptoms [1]. An increasing number of compounds with antibacterial activity are being isolated from endophytic fungi, including fumitremorgins B isolated from Phomopsis sp., and periconicins A and B from Periconia sp. [2, 3]. Exploitation of novel classes of antimicrobial metabolites is increasingly noticeable over recent years. A considerable body of research has investigated the diversity, ecological role, secondary metabolites and bioactivity of the endophytic fungi isolated from various medicinal plants [4].

The antibiotic resistance of bacterial pathogens has become a serious health concern and encourages the search for novel and efficient antimicrobial metabolites. There has therefore been a tremendous increase in interest in screening endophytes for their antimicrobial activities. Approximately 50 species belong to the genus Ophiopogon (Liliaceae) and most are found in eastern and southern Asia. Thirty-three Ophiopogon species and four varieties are available in China [5]. O. japonicus is a traditional medicine, admitted as one of functional food ingredient by the Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China. Over thousands of years, O. japonicus has been used to relieve symptoms such as coughing, phlegm, and heat in the lungs caused by bacterial infection [6–9]. Research has shown that the ‘Compound Ophiopogon japonicus Pill’ has displayed effective inhibition of Staphylococcus aureus and an extract from O. japonicus showed strong inhibition of malic mildew [10, 11]. Furthermore, previous studies have shown that O. japonicus inhibited germination and growth of several bacteria and fungi [12–14]. Previous research showed that ruscogenin from O. japonicus displayed remarkable antibacterial activity [15, 16], while the homoisoflavonoids from O. japonicus showed significant suppressive effects on eotaxin expression induced by IL-4 [17]. To the best of our knowledge, certain endophytic fungi can produce similar or the same active metabolites as their host plants [18]. We therefore think it necessary and timely to study the antimicrobial activities of the fungal endophytes associated with O. japonicus.

Our study was undertaken to screen endophytic fungi for activities against microorganisms and peptide deformylase (PDF), an essential enzyme in bacterial protein biosynthesis and shown to be an exciting target for the discovery of novel and efficient antibiotics. The antibacterial spectrum of PDF inhibitors currently published is primarily gram positive, including Staphylococci and Streptococci, and PDF inhibitors show no cross-resistance with existing antibiotic classes [19]. However, only limited information about endophytes from O. japonicus and their antibacterial activities has been gained to date. Screening of endophytic fungi from O. japonicus for antimicrobial activities will serve as a good basis for discovering new antibiotic agents.

Methods

Isolation and identification of endophytic fungi

Healthy roots and stems of O. japonicus were collected from Chongqing City, southwestern China. The host plant was identified by Professor Li Biao of the Institute of Medicinal Plant Development (IMPLAD), of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, and deposited in the Herbarium of the Department of IMPLAD, Beijing, China. Fungal isolation was carried out following Arnold [20], but with minor modifications. Samples were rinsed with running water and processed as follows. Samples were immersed in 75% ethanol for 1 min and in NaOCl (3%) for 5 min, washed three times with sterile distilled water, and then allowed to surface-dry on sterilized filter paper. Finally, samples were cut into 0.5 × 0.5 cm pieces and placed in Petri dishes (9 cm in diameter) on potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium (g/l; dextrose-20, agar-15, potato infusion-200), and cultured at 25°C in the dark for 1–2 weeks [21]. Active endophytic fungi were identified morphologically and by molecular analysis of the internal transcribed region (ITS) of the ribosomal DNA as described by Chen [22].

Preparation of crude fungal extracts

Crude extracts of endophytic fungi were prepared as described by Wang [23], but with slight modifications. Endophytic cultures were filtered using nylon nets to separate the culture broth and mycelia. All filtrates were transferred to larger conical flasks filled with five times the volume of 95% ethanol, stirred fully and left overnight, and then further concentrated in a vacuum to remove organic solvents. Mycelia were extracted twice with ultrasonic waves and again evaporated to dryness. EtOH extracts were dried by freeze drying, and then diluted with sterile distilled water to a concentration of 10 mg/ml and sterilized by filtration through a 0.22 μm millipore filter for antimicrobial activity assay. Extracts were dissolved in 1 ml dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and kept at 4°C for PDF inhibitory activity assay.

Peptide deformylase inhibitory fluorescence assay

The PDF gene was cloned and the product purified as previously described by the endpoint method [24–30]. Briefly, total DNA was extracted from cells of E. faecium ATCC6057 and the PDF gene was amplified by PCR using the primer pairs 5′-GGGAATTCCATATGATTACAATGG-3′ and 5′-CCGCTCGAGCTACTCGATCACC-3′. The gene was then cloned into the pET28a (+) vector and expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3). The PDF enzyme was purified with a Ni-NTA Superflow Column (Qiagen) using sodium phosphate buffer and an imidazole gradient. Purified enzyme and substrate (For-Met-Ala-Ser, Bachem) were mixed and then incubated with samples for 1 h at 37°C in 50 μl reaction volumes. Finally, 2 μl of a fluorescamine (Sigma) solution (2 μg/ml in DMSO) was added and then the fluorescence was determined with the excitation wavelength at 390 nm and the emission wavelength at 490 nm using a fluorescamine plate reader (Perkin Elmer).

In vitro antimicrobial activity

The crude extracts from the endophytes of O. japonicus were tested against one gram-positive bacterium (S. aureus), one gram-negative bacterium (E. coli), and one pathogenic fungus (C. neoformans), using a concentration of 1000 μg/ml. All indicator bacteria and fungi were obtained from the China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center (CGMCC) in Beijing, China. We tested the antimicrobial activity by MTT 3-(4,5-dimethyl thiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide colorimetric assay (MCA), as previously described [31, 32], but with a slight modification. Briefly, 80 μl of the indicator strain suspension with a density of 1 × 106 CFU/ml and 10 μl of sample were added into each well of a 96 well flat-bottom microtiter plate, and then incubated for 24 h/48 h at 37°C/28°C. After that, 10 μl of 5 mg/ml MTT solution was added into each well. Four hours later the cultures were centrifuged to precipitate formazan crystals, 200 μl of dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) was added, and then the cultures were incubated for 10 min at room temperature after supernatants were removed [33]. Finally, the optical density (OD) of the formazan solution was read at the wavelength of 570 nm, with 690 nm as a reference read-out. For every experiment, a background control, negative control, and positive control (gentamycin sulfate for bacteria, fluconazole for fungi) were included [34]. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was assigned to the lowest concentration for which no blue appeared.

Results and discussion

Of the total 30 endophytes obtained from O. japonicus, 22 endophytes (73.3%) were isolated from roots, and the remainder from stems. Endophytic fungi from roots were thus much more common than those from stems. The possible reason for this is that endophytic fungi are heterotrophic eucaryons. The roots play a very important role in synthesizing and storing of nutritive matter which will promote the metabolism, communication, and transport of nutrients in which the endophytes are involved.

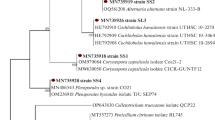

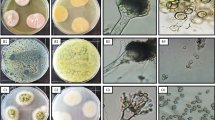

Our phylogenetic analysis indicated 12 active strains belonging to the phylum Ascomycota, and able to be classified into three taxonomic classes (Sordariomycetes, Deuteromycetes, and Eurotiomycetes). From morphology and ITS analysis we determined that these 12 active strains belonged to four genera (Figures 1 and 2).

Twelve isolates showed the inhibition of PDF enzyme levels, while showing resistance to S. aureus at the cellular level. Among the active isolates, Fusarium was the predominant genus with about 75% of strains, but the different isolates in this genus showed different strengths of antimicrobial activity. This is consistent with previous research [35–38]. All the antimicrobial activities of the extracts are shown in Table 1. We observed that crude extract of FBs from stems mostly displayed inhibitory activity on PDF, while the same extract showed no activity against S. aureus; illustrating that the extracts do not penetrate cell membranes.

We found that the activities of MCs were better than FBs. However, the FB of strain MD-09, a Gibberella sp., that exhibited the greatest inhibition S. aureus and C. neoformans (MIC = 20 μg/ml, 80 μg/ml), also exhibited significant activities on PDF. In addition, the MC of MD-09, MD-10, MD-12, MD-30, and the FB of MD-27 and MD-28 showed significantly inhibition of PDF (IR > 90%); the MC of MD-03, MD-09, MD-15, and the FB of MD-09, MD-29, and MD-30 inhibited more than 90% growth of S. aureus (MIC 20–40 μg/ml), while only the FB of MD-09 showed strong inhibition against C. neoformans. It thus appears that the MD-09 strain could be a source of bioactive antibacterial agents, and its metabolites are worth further research.

No extract displayed activity against E. coil. This is not consistent with previous research by Li [39], who studied the fungistatic and promoter action of O. japonicus, and found light concentration against E. coil while high concentration accreting growth of E. coil. The underlying reasons for this incompatibility are worth further investigation. We also screened for inhibition of HIV-1 integrase, but without obvious activity.

In addition, the crude extracts of Fusarium oxysporum and Fusarium poae, isolated from O. japonicus, were investigated for their prominent inhibition of several phytopathogens [40]. Many studies have indicated that Fusarium sp. are the most common species and a potent source of bioactive compounds among endophytes from medicinal plants. Previous research has shown the abundance of secondary metabolites of Fusarium that have antimicrobial activity. The pentaketide (CR377: 2-methylbutyraldehyde-substituted-α-pyrone) from a Fusarium sp. (in Selaginella pallescens) showed strong activity against Candida albicans[41]. A Fusarium sp. from Tripterygium wilfordii produced antimicrobial compounds such as subglutinol A and B [42]. In addition, beauvericin from Fusarium oxysporum isolated from the bark of Cinnamomum kanehirae significantly suppressed growth of methicillin-resistant S. aureus and Bacillus subtilis[43].

Furthermore, antimicrobial metabolites produced by the fermentation of endophytic fungi have many advantages, including no destruction of resources, sustainable use, easy large-scale industrial production and quality control. Our research supports the previous finding that endophytic fungi display high antimicrobial activities. We plan to research and develop new antibiotics based on our present findings.

Conclusions

The preliminary results of screening endophytic fungi from O. japonicus indicate their potential generation of bioactive metabolites for novel antibiotic discovery. Strain MD-09 displayed significant activity, revealing its potential for development as an antimicrobial drug, and clearly deserving further research.

Abbreviations

- MC:

-

Mycelium

- FB:

-

Fermentation broth

- IR:

-

Inhibition rate

- PDF:

-

Peptide deformylase

- OD:

-

Optical density

- PDA:

-

Potato dextrose agar.

References

Strobel G, Daisy B: Bioprospecting for microbial endophytes and their natural products. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2003, 67: 491-502. 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.491-502.2003.

Ni ZW, Li GH, Zhao PJ, Shen YM: Antimicrobial components of the endophytic fungal strain chaetomium globosum Ly50′ from maytenus hookeri. Nat Prod Rev (in Chinese). 2008, 20: 33-36.

Kim S, Shin DS, Lee T, Oh KB: Periconicins, two new fusicoccane diterpenes produced by an endophytic fungus Periconia sp. with antibacterial activity. J Nat Prod. 2004, 67: 448-450. 10.1021/np030384h.

Vaz AB, Mota RC, Bomfim MR, Vieira ML, Zani CL, Rosa CA, Rosa LH: Antimicrobial activity of endophytic fungi associated with Orchidaceae in Brazil. Can J Microbiol. 2009, 55: 1381-1391. 10.1139/W09-101.

Flora of China Editorial Committee of Chinese Academy of Sciences: Flora of China. 1978, Beijing: Science Press, 130-164.

Adinolfi M, Parilli Y, Zhu YX: Terpenoid glycosides from Ophiopogon japonicus roots. Phytochemistry. 1990, 29: 1696-1699. 10.1016/0031-9422(90)80151-6.

Zhu Y, Yan K, Tu G: Two homoisoflavones from Ophiopogon japonicus. Phytochemistry. 1987, 26: 2873-2874. 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)83615-8.

Chang HM, But PP: Pharmacology and applications of Chinese materia medica. 1986, Singapore: World Scientific Publishing, 543-

Xie W, Zhao Y, Zhang Y: Traditional Chinese medicines in treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus 2011. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2011, Article ID 726723: 13-10.1155/2011/726723.

Rao Y, Chen C, Zhao B: Study on the eliminating phlegm effect and bacteriostatic action of compound Maidong pills. Chin Hosp Pharm J. 2008, 28 (8): 615-617.

Zhang YM, Li RH, Yang ZL: Study on the bacteriostasis of some kinds of Chinese herbal medicine extracting solution. J Anhui Agri Sci. 2007, 35: 10594-10595.

Lin D: Study on allelopathy of dwarf lilyturf (Ophiopogon japonicus Ker-Gawl.). MS thesis. 2001, Japan: Miyazaki University, 15-47.

Lin D, Tsuzuki E, Sugimoto Y, Matsuo M: Effects of methanol extracts from Ophiopogon japonicus on rice blast fungus. International Rice Research Notes. 2003, 28: 27-28.

Lin D, Dong Y, Xu R: Preliminary study on the antifungal activity of the extracts from dwarf lilyturf (ophiopogon japonicus K.) roots on three kinds of plant pathogen. J Anhui Agri Sci. 2009, 37 (9): 4187-4188.

Nakanishi Y, Kaneda H: The chemical constitution research of Ophiopogon (Chinese). Yakugaku Zasshi. 1987, 107: 780-784.

Kou J, Sun Y, Lin Y, Cheng Z, Zheng W, Yu B, Xu Q: Anti-inflammatory activities of aqueous extract from Radix Ophiopogon japonicus and its two constituents. Biol Pharm Bull. 2005, 28: 1234-1238. 10.1248/bpb.28.1234.

Hung TM, Cao VT, Nguyen TD, Ryoo SW, Lee JH, Kim JC, Minkyun N, Jung HJ, KiHwan B, Byung SM: Homoisoflavonoid derivatives from the roots of Ophiopogon japonicus and their in vitro anti-inflammation activity. BMC Letters. 2010, 20: 2412-2416.

Xu LL, Han L, Wu JZ, Zhang QY, Zhang H, Huang BK, Rahman K, Qin LP: Comparative research of chemical constituents, antifungal and antitumor properties of ether extracts of Panx ginseng and its endophytic fungus. Phytomedicine. 2009, 16: 609-616. 10.1016/j.phymed.2009.03.014.

Apfel C, Banner DW, Bur D, Dietz M, Hirata T, Hubschwerlen C, Locher H, Page MGP, Pirson W, Rosse G, Specklin JL: Hydroxamic acid derivatives as potent peptide deformylase inhibitors and antibacterial agents. J Med Chem. 2000, 43: 2324-2331. 10.1021/jm000018k.

Arnold AE, Maynard Z, Gilbert GS, Coley PD, Kursat TA: Are tropical fungal endophytes hyperdiverse. Ecol Lett. 2000, 3: 267-274. 10.1046/j.1461-0248.2000.00159.x.

Bills GF: Isolation and analysis of endophytic fungal communities from woody plants. Endophytic fungi in grasses and woody plants: Systematics ecology and evolution. Edited by: Redlin SC, Carris LM. 1996, St. Paul, MN: APS Press, 31-65.

Chen J, Hu KX, Hou XQ, Guo SX: Endophytic fungi assemblages from 10 Dendrobium medicinal plants (Orchidaceae). World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011, 27: 1009-1016. 10.1007/s11274-010-0544-y.

Wang FW, Jiao RH, Cheng AB, Tan SH, Song YC: Antimicrobial potentials of endophytic fungi residing in Quercus variabilis and brefeldin A obtained from Cladosporium sp. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006, 235: 79-83.

Giglione C, Pierre M, Meinnel T: Peptide deformylase as a target for new generation, broad spectrum antimicrobial agents. Mol Microbiol. 2000, 36: 1197-1205.

Pei D: Peptide deformylase: A target for novel antibiotics. Emerging Ther Targets. 2001, 5: 23-40. 10.1517/14728222.5.1.23.

Yuan Z, Trias J, White RJ: Deformylase as a novel antibacterial target. Drug Discov Today. 2001, 6: 954-961. 10.1016/S1359-6446(01)01925-0.

Clements JM, Beckett RP, Brown A, Catlin G, Lobell M, Palan S, Thomas W, Whittaker M, Wood S, Salama S, Baker PJ, Rodgers HF, Barynin V, Rice DW, Hunter MG: Antibiotic activity and characterization of BB-3497, a novel peptide deformylase inhibitor. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001, 45: 563-570. 10.1128/AAC.45.2.563-570.2001.

Ki HN, Jung H, Amit P, Eunice EK, NamHyun C, Kwang YH: Insight into the antibacterial drug design and architectural mechanism of peptide recognition from the E. faecium peptide deformylase structure. Proteins. 2009, 74: 261-265. 10.1002/prot.22257.

Xian BT, Shu YS, Yue QZ: Identification of a New peptide deformylase gene from Enterococcus faecium and establishment of a New screening model targeted on PDF for novel antibiotics. Biomed Environ Sci. 2004, 17: 350-358.

Alicia FSM, Patricia O, Jon V: Over-expression of peptide deformylase in chloroplasts confers actinonin resistance, but is not a suitable selective marker system for plastid transformation. Transgenic Res. 2011, 20: 613-624. 10.1007/s11248-010-9447-9.

Mosmann T: Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983, 65: 55-63. 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4.

Denizot F, Lang R: Rapid colorimetric assay for cell growth and survival. J Immunol Methods. 1986, 89: 271-277. 10.1016/0022-1759(86)90368-6.

Wang FY, Cao LT, Hu SH: A rapid and accurate 3-(4, 5-dimethyl thiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide colorimetric assay for quantification of bacteriocins with nisin as an example. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2007, 8: 549-554. 10.1631/jzus.2007.B0549.

Zgoda JR, Porter JR: A Convenient microdilution method for screening natural products against bacteria and fungi. Pharm Biol. 2001, 39: 221-225. 10.1076/phbi.39.3.221.5934.

Xing YM, Chen J, Cui JL, Chen XM, Guo SX: Antimicrobial activity and biodiversity of endophytic fungi in Dendrobium devonianum and Dendrobium thyrsiflorum from Vietnam. Curr Microbiol. 2011, 62: 1218-1224. 10.1007/s00284-010-9848-2.

Cui JL, Guo SX, Dong HL, Xiao PG: Endophytic fungi from Dragon’s blood specimens: isolation, identification, phylogenetic diversity and bioactivity. Phytothe Res. 2011, 25: 1189-1195. 10.1002/ptr.3361.

Jiang DF, Ma P, Yang J, Wang X, Xu K, Huang Y, Chen S: Formation of blood resin in abiotic Dracaena cochinchinensis inoculated with Fusarium 9568D. Ying Yong Sheng Tai Xue Bao. 2003, 14: 477-478.

Li LY, Ding Y, Groth I, Menzel KD, Peschel G, Voigt K, Deng ZW, Sattler I, Lin WH: Pyrrole and indole alkaloids from an endophytic Fusarium incarnatum (HKI00504) isolated from the mangrove plant Aegiceras corniculatum. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008, 16: 7894-7899. 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.07.075.

Li XX, Pan XR, Wu LL, Zhang HL: Study on the fungistatic and promoter action of Ophiopogon japonicus (Thunb.) for E. Coli using microcalorimetric method. J Shandong University of TCM. 2001, 4: 307-309.

Liu CH, Liu TT, Yuan FF, Gu YC: Isolating endophytic fungi from evergreen plants and determining their antifungal activities. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2010, 4: 2243-2248.

Sean FB, Jon C: CR377, a New Pentaketide Antifungal Agent Isolated from an Endophytic Fungus. J Nat Prod. 2000, 3: 1447-1448.

Lee JC, Lobkovsky E, Nathan BP, Strobel G, Clardy J: Subglutinols a and B: immunosuppressive compounds from the endophytic fungus fusarium subglutinans. J Org Chem. 1995, 60: 7076-7077. 10.1021/jo00127a001.

Wang QX, Li SF, Zhao F, Dai HQ, Bao B, Ding R, Gao H, Zhang LX, Wen HA, Liu HW: Chemical constituents from endophytic fungus Fusarium oxysporum. Fitoterapia. 2011, 82: 777-781. 10.1016/j.fitote.2011.04.002.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6882/12/238/prepub

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 31070300, 31170016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

HQL was the principal investigator who designed the study, isolated the endophytic fungi, and wrote the manuscript. YMX participated in the design of the in vitro antimicrobial activity study and in writing the manuscript. JC carried out the the model of peptide deformylase inhibition fluorescence assay. DWZ carried out the development screening model for inhibitors targeting strand transfer reaction of HIV-1 integrase. SXG and CLW participated in the design of the study, revised the manuscript, and provided financial support. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, H., Xing, Y., Chen, J. et al. Antimicrobial activities of endophytic fungi isolated from Ophiopogon japonicus (Liliaceae). BMC Complement Altern Med 12, 238 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-12-238

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-12-238