Abstract

Background

Physical activity and exercise appear to improve psychological health. However, the quantitative effects of Tai Chi on psychological well-being have rarely been examined. We systematically reviewed the effects of Tai Chi on stress, anxiety, depression and mood disturbance in eastern and western populations.

Methods

Eight English and 3 Chinese databases were searched through March 2009. Randomized controlled trials, non-randomized controlled studies and observational studies reporting at least 1 psychological health outcome were examined. Data were extracted and verified by 2 reviewers. The randomized trials in each subcategory of health outcomes were meta-analyzed using a random-effects model. The quality of each study was assessed.

Results

Forty studies totaling 3817 subjects were identified. Approximately 29 psychological measurements were assessed. Twenty-one of 33 randomized and nonrandomized trials reported that 1 hour to 1 year of regular Tai Chi significantly increased psychological well-being including reduction of stress (effect size [ES], 0.66; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.23 to 1.09), anxiety (ES, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.29 to 1.03), and depression (ES, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.31 to 0.80), and enhanced mood (ES, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.20 to 0.69) in community-dwelling healthy participants and in patients with chronic conditions. Seven observational studies with relatively large sample sizes reinforced the beneficial association between Tai Chi practice and psychological health.

Conclusions

Tai Chi appears to be associated with improvements in psychological well-being including reduced stress, anxiety, depression and mood disturbance, and increased self-esteem. Definitive conclusions were limited due to variation in designs, comparisons, heterogeneous outcomes and inadequate controls. High-quality, well-controlled, longer randomized trials are needed to better inform clinical decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Mental illness affects 450 million people worldwide with 25% of the population affected in their lifetimes[1]. It is a leading cause of disability for people aged 15-44[2]. A growing list of psychological states including stress, anxiety, depression and mood disturbance have been linked to many chronic disorders such as coronary heart disease, cancer, diabetes and mental disorders as well as to accidents [3, 4]. Mental illness poses significant economic burdens to those involved, reduces productivity and increases health care costs[5]. Thus, there is an urgent need for inexpensive and effective strategies to promote psychological well-being and improve general heath status, especially for people with chronic conditions.

Over the past decade, evidence from epidemiological studies and clinical trials has demonstrated a positive association between physical fitness and psychological health. Numerous studies have shown that physical activity and exercise as well as mind-body practice reduce morbidity and mortality for coronary heart disease, hypertension, obesity, diabetes and osteoporosis, and improve the psychological status of the general population [6–10].

Tai Chi, a form of Chinese low impact mind-body exercise, has been practiced for centuries for health and fitness in the East and is currently gaining popularity in the West. Our previous investigations have shown that Tai Chi has potential benefits in treating a variety of chronic conditions [11–13]. Significant improvement has been reported in balance, strength, flexibility, cardiovascular and respiratory function, as well as pain reduction and improved quality of life [11]. Several recent reviews have suggested that Tai Chi appears to improve mood and enhance overall psychological well-being [11, 14, 15]. However, convincing quantitative evidence to estimate treatment effects has been lacking. No meta-analysis addressing any psychological outcomes with Tai Chi has ever been published. To better inform patients and physicians, we systematically reviewed the quantitative and qualitative relationship between Tai Chi and psychological health outcomes (stress, anxiety, depression, mood and self-esteem) by critically appraising and synthesizing the evidence from all published studies of healthy and chronically ill populations in the East and West.

Methods

Data sources and searches

We conducted a comprehensive computerized search of the medical literature using 8 English databases: MEDLINE (from 1950), PsycINFO (from 1806), CAB (from 1910), Health Star (from 1966), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (from 1991), CINAHL (from 1982), Global Health (from 1910) and Alt HealthWatch (from 1969). We also searched 3 major Chinese databases recommended by domain experts in evidence-based medicine in China. These included: China Hospital Knowledge Database (from 1994), China National Knowledge Infrastructure (from 1915) and WanFang Data (from 1980) through March 2009. We also searched reference lists of selected articles and reviews. The search terms for our review included "Tai Chi", "Tai Chi Chuan", "Tai Chi Chih", "ta'i chi," "tai ji," "Tai Ji Quan", and "taijiquan".

Study selection

Published articles that reported original data of randomized controlled trials (RCT), non-randomized comparison studies (NRS) and observational studies (OBS)[11] were eligible if they clearly defined a Tai Chi intervention [16]. We considered English and Chinese publications with at least 10 human subjects and evaluation of at least 1 of the following psychological health outcomes: (1) Psychological stress--an imbalance between perceived capabilities and situational demands with manifestations in emotional states, as well as physiological, psychological and behavioral responses; (2) Anxiety--an emotional state, characterized by a cognitive component (e.g. worry, self-doubt and apprehension) and a somatic component (e.g. heightened awareness of physiological responses such as heart rate, sweaty palms and tension); (3) Depression--a depressive state diagnosed with standard instruments and/or clinical interviews; (4) Mood--a pervasive and sustained emotion that colors the perception of the world; (5) Self-esteem--a awareness of good processed by an individual and a representation of how positive one feels about oneself in general [17–19]. We excluded articles such as reviews, case reports, and conference proceedings that did not provide primary data.

Data extraction and quality assessment

We assessed the characteristics of the original research and extracted data based on study design; demographics; type and duration of Tai Chi exercise and controls; the psychological measures of stress, depression, anxiety, mood and self-esteem; results and/or the authors' main conclusions. When data were not provided in publications, we contacted the authors for information. Two reviewers extracted data and assessed trial quality of each study independently. Interrater reliability was satisfactory (r ≥ 90). The methodological quality for the RCTs was evaluated based on the Jadad instrument [20], which takes into account whether a study described randomization, blinding, and withdrawals/dropouts.

Assessment of effect sizes and statistical analysis

When data were reported, we computed effect sizes (ES) in each study separately for stress, anxiety, depression and mood. ES was determined by calculating the standardized mean difference between groups. Overall outcome was assessed by pooling the ES of each study.

We calculated Hedges' g score for each study as a measure of ES. To correct for small sample size bias we computed the bias-corrected Hedges' g score for each measure. The magnitude of the ES (clinical effects) indicates: 0-0.19 = negligible effect, 0.20-0.49 = small effect, 0.50-0.79 = moderate effect, 0.80(+) = large effect. RCTs used the difference between the treatment and control group means. NRS used within-group difference between pretreatment and post-treatment means. In studies that involved more than one active intervention, we restricted our analyses to the Tai Chi and control groups. In view of significant heterogeneity, random-effect models were used for pooling. Heterogeneity was estimated with the I2 statistic for both RCTs and NRS. All analyses were conducted using Meta-Analyst 3.13 statistical software (Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA) [21].

Results

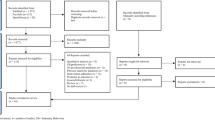

We reviewed 2579 English and Chinese articles and retrieved 61 full-text articles for detailed evaluation (Figure 1). Twenty-one studies were eliminated for not reporting original or relevant psychological outcome data. Ultimately, forty studies were identified for data abstraction and critical appraisal. Our search did not identify any unpublished literature.

Flow diagram of selection of articles for inclusion* *N = number of studies. aThese numbers add up to more than 40 because most studies assessed more than one psychological well-being state. bThese numbers add up to more than 21 because most studies assessed more than one psychological well-being state.

Table 1 lists the study design and number of studies and participants for each psychological domain. Table 2 describes the 40 studies including 17 RCTs, sixteen NRS and 7 OBS published between 1980 and 2009. They were conducted in 6 countries (USA, China, France, Germany, UK and Australia). There were 3072 healthy individuals (25 studies) and 745 patients with chronic conditions (14 studies); no data were available in 1 study [22]. Mean age ranged from 11 to 92 years, and 62% of participants were female. Various controls were compared among the 17 RCTs, with 6 studies having multiple types of controls. Fourteen of the 16 NRS were self-comparisons while 2 used routine activity as controls. Three of the 7 OBS used routine activity, two used aerobic activity, one was a self-comparison and 1 used the general population as comparisons.

Nine RCTs reported on randomization; eight of these described an appropriate method, one an inappropriate one. Ten RCTs reported on blinding; in all 10, outcome assessors were blinded. Twelve studies described withdrawals and dropouts. Dropout rates were high with 4 studies reporting dropouts ≥ 25%, and 3 others that reported attrition of 32%, 35%, and 47%. Eleven NRS and 6 OBS reported dropouts, with high rates listed for 3 NRS, reporting 57%, 43% and 33% (Table 2).

In all, we included 21 trials (12 RCTs and 9 NRS) of 33 that provided data on psychological quantitative measures in the meta-analysis. The 7 OBS were not included in the meta-analysis. Figure 2 displays the overall effects of Tai Chi on stress, anxiety, depression and mood. Table 3 qualitatively assesses the 19 studies that were excluded from the meta-analysis, showing study characteristics, methodology quality, and psychological outcomes. We describe below results for each outcome separately for studies that provided data for meta-analysis and those excluded from meta-analysis.

Effects of Tai Chi on stress, anxiety, depression and mood*. RCT = randomized controlled trial; NRS = nonrandomized comparison study (all the meta-analyzed NRS are self-comparison studies). N = number of participants. a McCain, 2008, included only Tai Chi versus wait list control (n = 119); Fransen 2007, included only Tai Chi versus control group (n = 97); Chen & Sun 1997, included only participants in Tai Chi group as pretreatment, posttreatment (n = 18); Sattin 2005, included only clinically depressed participants in Tai Chi and control arms (n = 43). b Dechamps, 2009, used an active control compared to Tai Chi. *The magnitude of the effect size (clinical effects) indicates: 0-0.19 = negligible effect, 0.20-0.49 = small effect, 0.50-0.79 = moderate effect, 0.80+ = large effect.

Tai Chi and Stress

Five RCTs, five NRS and 1 OBS, conducted in 4 countries (USA, Australia, Germany and China) reported the effects of Tai Chi on stress in 870 participants with ages ranging from 16 to 85 years (Table 2). Most studies employed subjective stress measures, including the Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale [23], Exercise Experiences Scale [24], Self-Perceived Stress score [25], Perceived Mental Stress score, Functional Assessment of HIV Infection [26], Impact of Event Scale [27], Perceived Stress Scale [28], and the Chinese Psychological Stress Scores. Two objective measures collected were body temperature[29] and salivary cortisol levels [30, 31].

Meta-analysis results

Four RCTs and 4 NRS with 444 participants assessed the effects of Tai Chi on stress in individuals with HIV [32, 33], elderly with symptomatic hip or knee osteoarthritis [34], healthy participants [29, 35–37], and elderly with cardiovascular disease risk factors [38]. Tai Chi was performed between 10 and 24 weeks (60 to 120 minutes, 1 to 4 times per week). We found statistically significant improvements in stress management and psychological distress (ES, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.23 to 1.09) (Figure 2a), with an I2 = 82%. This result remained significant upon dropping the study with the largest effect [29].

Studies not in meta-analysis

Three studies on stress were not included in the meta-analysis because 1 RCT and 1 NRS treated participants with Tai Chi practice for only one hour [39, 40], and the third was an OBS[41] (Table 3). The RCT with 96 healthy adults showed significantly decreased levels of stress in all groups after one hour of intervention (Tai Chi, meditation, brisk walking and neutral reading) [39]. The NRS also reported a single one-hour Tai Chi intervention that significantly reduced stress in healthy adults [40]. The OBS using a Chinese psychological stress questionnaire with 76 healthy Chinese elderly reported that 5 years of regular Tai Chi experience (>30 minutes and >3 times per week) significantly improved stress compared with less physical activity (<30 minutes and <3 times per week). This study, however, found no statistically significant difference between Tai Chi and regular activities of the same duration and frequency [41].

Summary

Overall, Tai Chi was positively associated with improved in stress levels in healthy adults, patients with HIV-related distress and elderly Chinese with cardiovascular disease risk factors [29, 32, 33, 35–41]. However, the overall study quality was modest with inadequate or no controls in the majority of studies.

Tai Chi and Anxiety

Five RCTs, 9 NRS and 5 OBS investigated the anxiety-reducing effect of Tai Chi in 1869 people from 4 countries (USA, UK, Australia and China) (Table 2). Seven studies used the Profile of Mood States Anxiety subscale[42] and 6 employed the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory [43]. The remainder used: the Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale [23], Connors' Teacher Rating Scale-Revised [44], Taylor Manifest Anxiety Scale [45], State Anxiety Inventory[46] and Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale [47]. Two disease-specific anxiety measures were used: the Symptom Checklist-90[48] and the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire [49].

Meta-analysis results

Two RCTs and 6 NRS with 359 participants including patients with symptomatic osteoarthritis [34], healthy adults [37, 50–52], elderly with cardiovascular disease risk factors [38], individuals with fibromyalgia [53], and adolescents with ADHD [54] found that Tai Chi practiced 2 to 4 times a week (30 to 60 minutes/time) for 5 to 24 weeks was associated with a significant reduction in anxiety (ES, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.29 to 1.03) (Figure 2b) with I2 = 76%.

Studies not in meta-analysis

Three RCTs, 2 NRS and 5 OBS were not included in the meta-analysis due to lack of sufficient quantitative data (Table 3). The duration of Tai Chi interventions ranged from 1 hour to 14 years (20 minutes to 1 hour, 1 to 3 times a week). Results from 2 RCTs with 134 subjects reported that Tai Chi practice for a single 1 hour session [39], or twice a week for 60 minutes/time over 8 weeks was associated with a significant reduction in anxiety scores both among HIV patients[55] and healthy adults [39, 40, 56]. Of note, the third RCT by Brown et al, who randomized 135 healthy adults to a Tai Chi-type activity, moderate or low intensity walking, walking with relaxation, or control reported results by gender [56]. The authors observed a significant decline in anxiety for women, but an insignificant decline in anxiety for men. Wall et al conducted an NRS with 11 6th and 8th graders who performed Yang style Tai Chi and Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction training (1 hour once a week, for 5 weeks) and found that the participants were "calmer, more peaceful and enjoyed improved sleep relaxation" [57]. The other NRS by Mills et al reported a nonsignificant decrease in tension-anxiety in 8 adults with Multiple Sclerosis [58]. Five large OBS of 1091 healthy adult participants, who practiced Tai Chi between 6 months and 14 years, showed significantly reduced anxiety measures compared to the general population [59], sedentary controls and people engaged in routine or moderate aerobic activity [60–63].

Summary

Overall, Tai Chi was positively associated with reduced anxiety using one or more anxiety measures, but overall study quality was modest.

Tai Chi and Depression

Ten RCTs, 6 NRS and 4 OBS examined the effects of Tai Chi on depression in 2008 subjects. Tai Chi intervention ranged from a single 1-hour session to 14 years. Six studies used the Center for Epidemiology Studies Depression Scale [64]. Seven used the Profile of Mood States Depression subscale [42], and the rest tests were the Beck Depression Inventory [65], Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire [49], Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale[66] and Self-Rating Scale-90.

Meta-analysis results

Nine RCTs and 4 NRS in 634 people examined the effects of Tai Chi on depression versus education, routine activity, waiting list and other forms of exercise as well as self-comparison among healthy adults [35, 37, 51, 67–69], individuals with rheumatoid arthritis [12], osteoarthritis [13, 34], fibromyalgia [53, 70], depression disorders [71], sedentary obese women [72], and elderly Chinese with cardiovascular disease risk factors [38]. Of note, only two studies involved participants with clinically diagnosed depression [68, 69, 71].

Overall, our analysis suggests that 6 to 48 weeks (40 minutes to 2 hours, 1 to 4 times a week) of Tai Chi practice resulted in significant depression-reduction effects compared to various controls (ES, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.31 to 0.80) (Figure 2c) with I2 = 62%. This result remained significant upon dropping the study with the large effect [71].

Studies not in meta-analysis

One RCT, 2 NRS and 4 OBS lacked sufficient quantitative detail for analysis (Table 3). Brown et al found a significant decrease in depression for women [56]. The studies by Mills and Jin also reported significant decreases in depression after 8 weeks [58] and an hour of Tai Chi practice, respectively [40]. Four OBS in 842 healthy Chinese subjects showed that regular Tai Chi practice up to 14 years demonstrated statistically significant reductions in depressive symptoms compared with routine activity [59, 60, 62, 63].

Summary

Overall, evidence from most studies showed that Tai Chi tended to reduce depression. This result was associated with improvement in symptoms and physical function in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis, as well as improvement in the immune response of healthy elderly participants. However, the vast majority of the studies suffer from less rigorous designs and were conducted on "healthy" populations with only two studies reporting results on participants diagnosed with clinical depression [68, 71].

Tai Chi and Mood

Evidence on the effects of Tai Chi on mood was examined from 4 RCTs, eight NRS and 3 OBS in 1613 subjects. Duration of Tai Chi practice ranged from 1 hour to 14 years (1 to 7 times a week). The majority of studies reported the total score of the Profile of Mood States scale [42]; other measures were the Functional Assessment of HIV Infection [26], Positive and Negative Affect Schedule [73], Life Satisfaction in the Elderly Scale [74], Symptom Checklist-90 [48], Conners' Teacher Rating Scale-Revised [44], and Multiple Affect Adjective Checklist-Revised [75].

Meta-analysis results

Two RCTs and 4 NRS assessed the effects of Tai Chi on mood in healthy elderly [35, 76], individuals with HIV [32], elderly Chinese with cardiovascular disease risk factors [38], and adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder[54]. Tai Chi was performed between 5 and 24 weeks (30 to 90 minutes, 1 to 4 times per week). Tai Chi significantly improved mood compared to various controls with overall ES of (0.45; 95% CI, 0.20 to 0.69), and the I2 = 25% (Figure 2d).

Studies not in meta-analysis

Two RCTs, four NRS and 3 OBS lacked sufficient quantitative detail for analysis. Brown et al reported that 16 weeks of Tai Chi showed significantly elevated mood for women [56]. Significant improvement in mood was also reported in a RCT following short-term Tai Chi training [39]. Results from 3 NRS reported non-significant improvements in mood following 7 weeks to 1 year of Tai Chi [22, 77, 78] and one NRS reported a significant decrease in mood disturbance after an hour of Tai Chi practice [40]. Similarly, 3 OBS of 799 subjects reported that 0.5 to 14 years of Tai Chi practice significantly improved mood disturbance in healthy participants [62, 63].

Summary

Overall, evidence suggested short and long-term Tai Chi practice had favorable effects on mood among healthy adults [35, 37, 39, 40, 56, 62, 63, 76], elderly with cardiovascular risk factors [38], obese women [32], and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder [54]. However, the overall study quality was poor with inadequate or no controls in the majority of studies.

Tai Chi and Self-esteem

Meta-analysis results

Only 3 RCTs and 1 NRS evaluated the effects of Tai Chi on self-esteem in 425 subjects and there are no sufficient quantitative data for meta-analysis.

Studies not in meta-analysis

In these 4 trials, Tai Chi practice lasted from 12 to 26 weeks (45 to 60 minutes, 2 to 3 times per week). Among the measurements employed were: Rosenberg's 10-item Global Self-Esteem Scale [79], the Chinese version of the State Self-Esteem Scale [80], Sonstroem Physical Examination Scale [81] and the Body Cathexis Score [82]. Results from 3 RCTs involving 286 subjects reported that 12 to 16 weeks of Tai Chi was associated with increases in self-esteem scores compared with control groups [56, 83, 84]. Two RCTs, however, reported nonsignificant results [56, 84]. A significant improvement in self-esteem was reported in a recent 26 week NRS that compared Tai Chi to routine activity among 139 Chinese healthy elderly [85].

Summary

Overall, Tai Chi was positively associated with improvement in self-esteem although no meta-analysis result was provided.

Discussion

Tai Chi, a form of low impact mind-body exercise, has spread worldwide over the past two decades. This systematic review and meta-analysis summarizes and updates results of the effects of Tai Chi exercise on health outcomes[11] in terms of psychological effects in various populations.

Evidence accrued from clinical trials and observational studies indicates that Tai Chi-- both short and long-term--appears to have mental health benefits in promoting psychological well-being, self-esteem and life satisfaction among healthy subjects and patients with chronic conditions. Specifically, twenty-three of the 33 RCTs and NRS from our quantitative meta-analysis and qualitative evidence synthesis reported that 1 hour to 1 year of regular Tai Chi activity significantly reduced stress, anxiety and depression, and enhanced mood in healthy adults and patients with chronic conditions. The 7 OBS with relatively large sample sizes reinforce the beneficial effects of Tai Chi on psychological health, although bias may be inherent in these observational data.

Our review is congruent with other recent epidemiological reports, experimental trials and literature reviews supporting the fact that physical activity and exercise are associated with better psychological health [8, 14, 15, 86]. Biddle et al recently reviewed evidence on physical activity and exercise in relation to different aspects of mental health. They found that exercise is associated with the strongest anxiety-reduction effects and emphasized the causal link between physical activities and reduction in clinically-defined depression [18]. In particular, evidence from meta-analyses and narrative reviews demonstrates that physical activity and exercise as well as mind-body practice have consistently been associated with positive mood and affect [10, 14, 15, 87–89].

There is insufficient evidence to find any dose-response effect of Tai Chi for psychological outcomes. The studies included in this review exhibit a wide variety of Tai Chi styles, frequency, duration and follow up. The Yang style was used in 17 studies. The majority of studies featured Tai Chi 2 to 3 times per week (frequency), for at least 20 minutes and for an average of 40 to 60 minutes per session (duration). The length of exercise programs ranged from 5 weeks to 1 year, or a single hour for two studies. In the OBS, Tai Chi duration ranged from 6 months to 14 years, and all studies found positive psychological benefits. Few studies reported the intensity and relationship between adherence to Tai Chi and positive psychological effects. Further studies are needed to optimize effective evidence-based dose-response effects and should strictly demand descriptions of intensity, frequency, duration and adherence of the Tai Chi exercise.

Tai Chi appears to be an effective therapeutic modality to improve psychological well-being among various populations. However, it is still difficult to draw firm conclusions. First, we did not include any unpublished studies. The overall methodological quality of previous studies is unsatisfactory, consisting mostly of small sized or nonrandomized comparisons. Given the few high quality RCTs available for investigation, our review is limited by wide variations in methodological rigor of clinical trials and observational studies. Second, the heterogeneous amalgamation of instruments used to collect clinical psychological health data restricts our ability to evaluate differences in these outcomes. Third, it remains unclear whether Tai Chi mind-body exercise provides equal or superior psychological benefits compared to moderate-intensity aerobic exercises. Fourth, most studies failed to provide objective measures of stress and anxiety such as salivary cortisol level, blood pressure or heart rate, and some studies only reported a subset of psychological outcomes. Due to the limited physiological variables in our analyses, we were unable to analyze the effect of Tai Chi on physiological effects. Fifth, the studies included in the meta-analyses demonstrated a relatively high degree of heterogeneity. Various patient populations were used, and most studies involved healthy people. There were also many variations between the included studies with regard to methodological quality (eg, problems of randomization, allocation concealment, or reporting results), which prohibited us from analyzing the quantitative evidence. However, it is difficult to compare results across studies because they were assessed at different time points. Additionally, all the studies published in mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan reported unanimously positive results. Differences in methodological rigor between eastern and western studies may be potential sources of heterogeneity, and publication bias may vary across countries and cultures.

Few published studies have specifically investigated the underlying mechanism of action of Tai Chi's effects on psychological health. Many intermediate, but unidentified, variables may lie along the pathway from Tai Chi to improved psychological well-being. Measures of psychological variables and a multitude of other outcome measures are empirically inter-related, and treatment of each outcome can reciprocally and exponentially improve the other. Improvement of psychological status is also associated with improvement in other clinical outcomes such as arthritic pain as well as health status [90]. The possible mechanisms for enhanced psychological health resulting from Tai Chi mind-body exercise may therefore act through its beneficial influence on biological, physiological, cardiovascular, neurological, and immunological effects as well as overall well-being [11, 67, 89, 91].

Conclusions

In conclusion, the results of these studies suggest that Tai Chi may be associated with improvements in psychological well-being including reduced stress, anxiety, depression and mood disturbance, and increased self-esteem. High-quality, rigorous, prospective, well-controlled randomized trials with appropriate comparison groups and validated outcome measures are needed to further understand the effects of Tai Chi as an intervention for specific psychological conditions in different populations. Knowledge about the physiological and psychological effects of Tai Chi exercise may lead to new complementary and alternative medical approaches to promote health, treat chronic medical conditions, better inform clinical decisions and further explicate the mechanisms of successful mind-body medicine.

References

Levav I, Rutz W: The WHO World Health Report 2001 new understanding--new hope. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2002, 39: 50-56.

The World Health Report 2003: Shaping the Future: Burden of disease in DALYs by cause, sex, and mortality stratum in WHO regions, estimates for 2002. . 2003, World Health Organization, 160-165.

Hiroeh U, Appleby L, Mortensen PB, Dunn G: Death by homicide, suicide, and other unnatural causes in people with mental illness: a population-based study. Lancet. 2001, 358: 2110-2112. 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)07216-6.

Januzzi JL, Stern TA, Pasternak RC, DeSanctis RW: The influence of anxiety and depression on outcomes of patients with coronary artery disease. Arch Intern Med. 2000, 160: 1913-1921. 10.1001/archinte.160.13.1913.

Mental illness statistics and facts. Vol. 2009. Accessed June 29, 2009., [http://www.selfhelparticles.net/]

Janisse HC, Nedd D, Escamilla S, Nies MA: Physical activity, social support, and family structure as determinants of mood among European-American and African-American women. Women Health. 2004, 39: 101-116. 10.1300/J013v39n01_06.

Chow YW, Tsang HW: Biopsychosocial effects of qigong as a mindful exercise for people with anxiety disorders: a speculative review. J Altern Complement Med. 2007, 13: 831-839. 10.1089/acm.2007.7166.

Smith PJ, Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Georgiades A, Hinderliter A, Sherwood A: Effects of exercise and weight loss on depressive symptoms among men and women with hypertension. J Psychosom Res. 2007, 63: 463-469. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.05.011.

Broman-Fulks JJ, Storey KM: Evaluation of a brief aerobic exercise intervention for high anxiety sensitivity. Anxiety, Stress & Coping. 2008, 21: 117-128.

Tsang HW, Chan EP, Cheung WM: Effects of mindful and non-mindful exercises on people with depression: a systematic review. Br J Clin Psychol. 2008, 47: 303-322. 10.1348/014466508X279260.

Wang C, Collet JP, Lau J: The effect of Tai Chi on health outcomes in patients with chronic conditions: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2004, 164: 493-501. 10.1001/archinte.164.5.493.

Wang C: Tai Chi improves pain and functional status in adults with rheumatoid arthritis: results of a pilot single-blinded randomized controlled trial. Med Sport Sci. 2008, 52: 218-229. full_text.

Wang C, Schmid CH, Hibberd PL, Kalish R, Roubenoff R, Rones R, McAlindon T: Tai Chi is effective in treating knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 61: 1545-1553. 10.1002/art.24832.

Sandlund ES, Norlander T: The effects of tai chi chuan relaxation and exercise on stress responses and well-being: an overview of research. International Journal of Stress Management. 2000, 7: 139-149. 10.1023/A:1009536319034.

Dechamps A, Lafont L, Bourdel-Marchasson I: Effects of Tai Chi exercises on self-efficacy and psychological health. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act. 2007, 4: 25-32. 10.1007/s11556-007-0015-0.

Sports C: Simplified "Taijiquan". 1983, Beijing, China: China Publications Center, 2

Cox RH: Sport Psychology: Concepts and Applications. 1985, Dubuque (IA): Wm. C. Brown Publishers, 2

Biddle S, Fox KR, Boutcher SH, (eds): Physical Activity and Psychological Well-Being. 2000, New York (NY): Routledge

American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV-TR. 2000, American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ: Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary?. Control Clin Trials. 1996, 17: 1-12. 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4.

Wallace BC, Schmid CH, Lau J, Trikalinos TA: Meta-Analyst: software for meta-analysis of binary, continuous and diagnostic data. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009, 9: 80-10.1186/1471-2288-9-80.

Mack C: A theoretical model of psychosomatic illness in Blacks and an innovative treatment strategy. J Black Psychol. 1980, 7: 27-43. 10.1177/009579848000700103.

Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH: The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther. 1995, 33: 335-343. 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U.

McAuley E, Courneya KS: The Subjective Exercise Experiences Scale: Development and preliminary validation. J Sport Exercise Psy. 1994, 16: 163-177.

Gilmore GD, Campbell MD, Becker BL: Needs assessment strategies for health education and health promotion. 1989, Indianapolis (IN): Benchmark

Peterman AH, Cella D, Mo F, McCain N: Psychometric validation of the revised Functional Assessment of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection (FAHI) quality of life instrument. Qual Life Res. 1997, 6: 572-584. 10.1023/A:1018416317546.

Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W: Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med. 1979, 41: 209-218.

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R: A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983, 24: 385-396. 10.2307/2136404.

Sun WY, Dosch M, Gilmore GD, Pemberton W, Scarseth T: Effects of Tai Chi Chuan Program on Hmong American Older Adults. Educ Gerontol. 1996, 22: 161-167. 10.1080/0360127960220202.

The stress response: Always good and when it is bad. 2005, Warsaw-New York: Medical Science International

King SL, Hegadoren KM: Stress hormones: how do they measure up?. Biol Res Nurs. 2002, 4: 92-103. 10.1177/1099800402238334.

McCain NL, Gray DP, Elswick RK, Robins JW, Tuck I, Walter JM, Rausch SM, Ketchum JM: A randomized clinical trial of alternative stress management interventions in persons with HIV infection. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008, 76: 431-441. 10.1037/0022-006X.76.3.431.

Robins JL, McCain NL, Gray DP, Elswick RK, Walter JM, McDade E: Research on psychoneuroimmunology: tai chi as a stress management approach for individuals with HIV disease. Appl Nurs Res. 2006, 19: 2-9. 10.1016/j.apnr.2005.03.002.

Fransen M, Nairn L, Winstanley J, Lam P, Edmonds J: Physical activity for osteoarthritis management: a randomized controlled clinical trial evaluating hydrotherapy or Tai Chi classes. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 57: 407-414. 10.1002/art.22621.

Li F, Duncan TE, Duncan SC, McAuley E, Chaumeton NR, Harmer P: Enhancing the psychological well-being of elderly individuals through Tai Chi exercise: A latent growth curve analysis. Struct Equ Model. 2001, 8: 53-83. 10.1207/S15328007SEM0801_4.

Esch T, Duckstein J, Welke J, Braun V: Mind/body techniques for physiological and psychological stress reduction: stress management via Tai Chi training - a pilot study. Med Sci Monit. 2007, 13: CR488-497.

Chen X, Liu J, Qiu PX: Effect of Taijiquan exercise on mental health of middle and old aged females. J Shanghai Univ Sport. 2005, 29: 79-82.

Taylor-Piliae RE, Haskell WL, Waters CM, Froelicher ES: Change in perceived psychosocial status following a 12-week Tai Chi exercise programme. J Adv Nurs. 2006, 54: 313-329. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03809.x.

Jin P: Efficacy of Tai Chi, brisk walking, meditation, and reading in reducing mental and emotional stress. J Psychosom Res. 1992, 36: 361-370. 10.1016/0022-3999(92)90072-A.

Jin P: Changes in heart rate, noradrenaline, cortisol and mood during Tai Chi. J Psychosom Res. 1989, 33: 197-206. 10.1016/0022-3999(89)90047-0.

Wang L, Wang S: Effect of shadowboxing on the psychological factors in middle and aged people. Chin J Clin Rehabil. 2004, 8: 1128-1129.

McNair DM, Lorr M, Droppleman LF: Manual for the Profile of Mood States. 1971, San Diego (CA): Educational and Industrial Testing Service

Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobb GA: Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y). 1983, Palo Alto (CA): Consulting Psychologists' Press

Goyette CH, Conners CK, Ulrich RF: Normative data on revised Conners Parent and Teacher Rating Scales. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1978, 6: 221-236. 10.1007/BF00919127.

Taylor JA: A personality scale of manifest anxiety. J Abnorm Psychol. 1953, 48: 285-290. 10.1037/h0056264.

Spielberger C: The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. 1970, Palo Alto (CA): Consulting Psychological Press

Zung WWK: A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics. 1971, 12: 371-379.

Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Covi L: SCL-90: an outpatient psychiatric rating scale--preliminary report. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1973, 9: 13-28.

Burckhardt CS, Clark SR, Bennett RM: The fibromyalgia impact questionnaire: development and validation. J Rheumatol. 1991, 18: 728-733.

Tsai JC, Wang WH, Chan P, Lin LJ, Wang CH, Tomlinson B, Hsieh MH, Yang HY, Liu JC: The beneficial effects of Tai Chi Chuan on blood pressure and lipid profile and anxiety status in a randomized controlled trial. J Altern Complement Med. 2003, 9: 747-754. 10.1089/107555303322524599.

Li J: Effect of Tai Chi on psychological health for college students. J Guangdong Educ Inst. 2004, 24: 126-128.

Chen W, Sun W: Tai Chi Chuan, an alternative form of exercise for health promotion and disease prevention for older adults in the community. Int Q Community Health Educ. 1997, 16: 333-339. 10.2190/FDPE-VVG2-VNTR-N2DK.

Taggart HM, Arslanian CL, Bae S, Singh K: Effects of T'ai Chi exercise on fibromyalgia symptoms and health-related quality of life. Orthop Nurs. 2003, 22: 353-360. 10.1097/00006416-200309000-00013.

Hernandez-Reif M, Field TM, Thimas E: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Benefits from Tai Chi. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2001, 5: 120-123. 10.1054/jbmt.2000.0219.

Galantino ML, Shepard K, Krafft L, Laperriere A, Ducette J, Sorbello A, Barnish M, Condoluci D, Farrar JT: The effect of group aerobic exercise and t'ai chi on functional outcomes and quality of life for persons living with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Altern Complement Med. 2005, 11: 1085-1092. 10.1089/acm.2005.11.1085.

Brown DR, Wang Y, Ward A, Ebbeling CB, Fortlage L, Puleo E, Benson H, Rippe JM: Chronic psychological effects of exercise and exercise plus cognitive strategies. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995, 27: 765-775.

Wall RB: Tai Chi and mindfulness-based stress reduction in a Boston Public Middle School. J Pediatr Health Care. 2005, 19: 230-237. 10.1016/j.pedhc.2005.02.006.

Mills N, Allen J, Carey-Morgan S: Does Tai Chi/Qi Gong help patients with Multiple Sclerosis?. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2000, 4: 39-48. 10.1054/jbmt.1999.0139.

Liu Y, Zhang YZ: Influence of Taiji ball play on collegiate students' mentality. J Wuhan Inst of Phys Edu. 2000, 34: 211-212.

Yang S, Long YF, Huang YX: Effects of Taiji exercise on the psychology and the functions of the autonomic nervous systems of the middle aged and elderly. Chin J Phys Med Rehabil. 2004, 26: 348-350.

Bond DS, Lyle RM, Tappe MK, Seehafer RS, D'Zurilla TJ: Moderate Aerobic Exercise, T'ai Chi, and Social Problem-Solving Ability in Relation to Psychological Stress. Int J Stress Manag. 2002, 9: 329-343. 10.1023/A:1019934417236.

Chen KM, Snyder M, Krichbaum K: Tai Chi and well-being of Taiwanese community-dwelling elders. Clin Gerontol. 2001, 24: 137-156. 10.1300/J018v24n03_12.

Long Y, Zang CL, Tang CZ: Effect of Yang style Tai Chi on sleep, mood for old adults. Occup Health. 2000, 15: 211-212.

Radloff LS: The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psych Meas. 1977, 1: 385-401. 10.1177/014662167700100306.

Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J: An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961, 4: 561-571.

Zung WW: A Self-Rating Depression Scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965, 12: 63-70.

Irwin MR, Olmstead R, Oxman MN: Augmenting immune responses to varicella zoster virus in older adults: a randomized, controlled trial of Tai Chi. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007, 55: 511-517. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01109.x.

Sattin RW, Easley KA, Wolf SL, Chen Y, Kutner MH: Reduction in fear of falling through intense tai chi exercise training in older, transitionally frail adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005, 53: 1168-1178. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53375.x.

Wolf SL, Sattin RW, Kutner M, O'Grady M, Greenspan AI, Gregor RJ: Intense tai chi exercise training and fall occurrences in older, transitionally frail adults: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003, 51: 1693-1701. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51552.x.

Wang C, Schmid CH, Kalish R, Yinh J, Goldenberg DL, Rones R, McAlindon T: Tai Chi is effective in treating fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 60: S526-

Chou KL, Lee PW, Yu EC, Macfarlane D, Cheng YH, Chan SS, Chi I: Effect of Tai Chi on depressive symptoms amongst Chinese older patients with depressive disorders: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004, 19: 1105-1107. 10.1002/gps.1178.

Dechamps A, Gatta B, Bourdel-Marchasson I, Tabarin A, Roger P: Pilot study of a 10-week multidisciplinary Tai Chi intervention in sedentary obese women. Clin J Sport Med. 2009, 19: 49-53. 10.1097/JSM.0b013e318193428f.

Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A: Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988, 54: 1063-1070. 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063.

Salamon MJ, Conte VA: Manual for the Salamon-Conte Life Satisfaction in the Elderly Scale. 1984, Odessa (FL): Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc

Zuckerman M, Lubin B, Rinck CM: Construction of new scales for the Multiple Affect Adjective Check List. J Behav Assess. 1983, 5: 119-129. 10.1007/BF01321444.

Ross MC, Bohannon AS, Davis DC, Gurchiek L: The effects of a short-term exercise program on movement, pain, and mood in the elderly. Results of a pilot study. J Holist Nurs. 1999, 17: 139-147. 10.1177/089801019901700203.

Gibb H, Morris CT, Gleisberg J: A therapeutic programme for people with dementia. Int J Nurs Pract. 1997, 3: 191-199. 10.1111/j.1440-172X.1997.tb00099.x.

Fu CY, Wong AF, Wang YZ: The effects of Tai Chi on psychological balance. J Chin Rehabil. 1996, 11: 88-89.

Rosenberg M: Society and the adolescent self-image. 1965, Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press

Heatherton TF, Polivy J: Development and validation of a scale for measuring state self-esteem. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991, 60: 895-910. 10.1037/0022-3514.60.6.895.

Sonstroem RJ: Physical estimation and attraction scales: Rationale and research. Med Sci Sports. 1978, 10: 97-102.

Secord PF, Jourard SM: The appraisal of body-cathexis: body-cathexis and the self. J Consult Psychol. 1953, 17: 343-347. 10.1037/h0060689.

Mustian KM, Katula JA, Gill DL, Roscoe JA, Lang D, Murphy K: Tai Chi Chuan, health-related quality of life and self-esteem: a randomized trial with breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2004, 12: 871-876. 10.1007/s00520-004-0682-6.

Kutner NG, Barnhart H, Wolf SL, McNeely E, Xu T: Self-report benefits of Tai Chi practice by older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1997, 52B: P242-246.

Lee L, Lee DT, Woo J: Effect of Tai Chi on state self-esteem and health-related quality of life in older Chinese residential care home residents. J Clin Nurs. 2007, 16: 1580-1582. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.02061.x.

Hill K, Smith R, Fearn M, Rydberg M, Oliphant R: Physical and psychological outcomes of a supported physical activity program for older carers. J Aging Phys Act. 2007, 15: 257-271.

Conn V, Hafdahl A, Porock D, McDaniel R, Nielsen P: A meta-analysis of exercise interventions among people treated for cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2006, 14: 699-712. 10.1007/s00520-005-0905-5.

Sephton SE, Salmon P, Weissbecker I, Ulmer C, Floyd A, Hoover K, Studts JL: Mindfulness meditation alleviates depressive symptoms in women with fibromyalgia: results of a randomized clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 57: 77-85. 10.1002/art.22478.

Lush E, Salmon P, Floyd A, Studts JL, Weissbecker I, Sephton SE: Mindfulness meditation for symptom reduction in fibromyalgia: psychophysiological correlates. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2009, 16: 200-207. 10.1007/s10880-009-9153-z.

Wilson IB, Cleary PD: Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA. 1995, 273: 59-65. 10.1001/jama.273.1.59.

Yeh GY, Wang C, Wayne PM, Phillips R: Tai chi exercise for patients with cardiovascular conditions and risk factors: a systematic review. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2009, 29: 152-160.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6882/10/23/prepub

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Marcie Griffith and Aghogho Okparavero for their help with review of this study. Dr. Wang is supported in part by the American College of Rheumatology Research and Education Health Professional Investigator Award, the Boston Older Americans Independence Center Research Career Development Award and R21AT003621 from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM). The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine or the National Institutes of Health. The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

CW obtained funding for the study. CW, BK and CS designed the study. CW, RB, JR, BK and CS conducted the research. RB and CS conducted the meta-analysis. CW wrote the first draft of the manuscript. CW, CS, RB, JR, BK and TS participated in the revision of subsequent draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, C., Bannuru, R., Ramel, J. et al. Tai Chi on psychological well-being: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement Altern Med 10, 23 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-10-23

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-10-23