Abstract

Background

Complementary therapies are widespread but controversial. We aim to provide a comprehensive collection and a summary of systematic reviews of clinical trials in three major complementary therapies (acupuncture, herbal medicine, homeopathy). This article is dealing with herbal medicine. Potentially relevant reviews were searched through the register of the Cochrane Complementary Medicine Field, the Cochrane Library, Medline, and bibliographies of articles and books. To be included articles had to review prospective clinical trials of herbal medicines; had to describe review methods explicitly; had to be published; and had to focus on treatment effects. Information on conditions, interventions, methods, results and conclusions was extracted using a pre-tested form and summarized descriptively.

Results

From a total of 79 potentially relevant reviews pre-selected in the screening process 58 met the inclusion criteria. Thirty of the reports reviewed ginkgo (for dementia, intermittent claudication, tinnitus, and macular degeneration), hypericum (for depression) or garlic preparations (for cardiovascular risk factors and lower limb atherosclerosis). The quality of primary studies was criticized in the majority of the reviews. Most reviews judged the available evidence as promising but definitive conclusions were rarely possible.

Conclusions

Systematic reviews are available on a broad range of herbal preparations prescribed for defined conditions. There is very little evidence on the effectiveness of herbalism as practised by specialist herbalists who combine herbs and use unconventional diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In this second part of our series on systematic reviews in complementary therapies we report our findings on herbal medicines. Herbal medicines (defined as preparations derived from plants and fungi, for example by alcoholic extraction or decoction, used to prevent and treat diseases) are an essential part of traditional medicine in almost any culture [1]. In industrialized countries herbal drugs and supplements are an important market. Some countries like Germany have a long tradition in the use of herbal preparations marketed as drugs and figures for prescriptions and sales are stable or slightly declining [2]. In the US and the UK herbal medicinal products are marketed as "food supplements" or "botanical medicines". In recent years sales of such products have been increasing strongly in these countries [3, 4]. In the Third World herbs are mainly used by traditional healers [5].

Methods

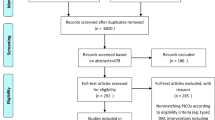

A detailed description of the methods used in this review of reviews is given in the first part of this series [6]. For searches in Medline 50 single plant names and the 'exploded' term 'medicinal plants' were combined with the standard search strategy for systematic reviews. As a specific intervention-related inclusion criterion we required that reports reviewed prospective (not necessarily controlled) clinical trials of substances extracted from plants in humans. Reviews dealing with single substances (e.g., artemisin derivatives) derived from plants were excluded on the grounds that such agents are comparable to conventional drugs. Disease-oriented reviews including a variety of interventions were included only if they reviewed at least 4 herbal medicine trials.

Results

From a total of 79 potentially relevant reviews preselected in the literature screening process, 58 (published in 65 papers) met the inclusion criteria [7–71]. Eleven reports were not truly systematic reviews (not meeting inclusion criterion 2) [72–82], 5 dealt with isolated substances of plant origin [83–87] and 4 were excluded for other reasons (one disease- focused review with less than 4 herbal medicine trials [88], one review not on preventative or therapeutic use [89], two reviews not truly herbal medicine [90, 91]).

More than half of the reports reviewed gingko, hypericum or garlic preparations. No less than 13 systematic reviews dealed with ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba) extracts (see table 1). Seven of these reviewed trials (total number of trials covered in any of the reviews 15) in patients with intermittent claudication [7–13]. Most of these reviews concluded that ginkgo extracts were significantly more effective than placebo in increasing measures like walking distance but the clinical relevance of the effects was felt to be moderate by some reviewers. The five reviews dealing with dementia and cerebral insufficiency (total number of trials included about 50) all draw positive conclusions [13–17]. However, many of the older trials were in patients with minor cognitive impairment and more evidence is needed to decide whether ginkgo extracts have clinically relevant beneficial effects in more severe forms of dementia. Finally, one review found that ginkgo extracts might be effective in the treatment of tinnitus [18] and another found insufficient evidence for efficacy in patients with macular degeneration [19].

The effectiveness of St. John's wort (Hypericum perforatum) extracts in depression was investigated in nine reviews [20–30] (total number of trials covered 29; see table 2). Mainly due to slight differences in the inclusion criteria (for example, restriction to trials with a minimum of 6 weeks observation or with a minimum quality score) the respective study collections differed to a considerable amount. However, the conclusions were very similar. Hypericum extracts have been shown to be superior to placebo in mild to moderate depressive disorders. There is growing evidence that hypericum is as effective as other antidepressants for mild to moderate depression and causes fewer side effects but further trials are still needed to establish long-term effectiveness and safety.

Eight reviews have been performed on garlic (Allium sativum) for cardiovascular risk factors [31–38] (total number of trials covered about 50) and lower limb atherosclerosis [39] (see table 2). A modest short-term effect over placebo on lipid-lowering seems to be established but the clinical relevance of these effects is uncertain. Data from randomised trials on cardiovascular mortality are not available. Effects on blood pressure seem to be at best minor. The available results on fibrinolytic activity and platelet aggregation are promising but insufficient to draw clear conclusions. A specific problem in research on garlic is the great variety of garlic preparations used: the exact content of bioactive ingredients in these is often unclear.

Three reviews (covering a total of about 30 trials) have been performed on preparations containing extracts of Echinacea (Echinacea purpurea, pallida or angustifolia), two of which by the same study group [40–43]. The results suggest that Echinacea preparations may have some beneficial effects mainly in the early treatment of common colds. Similar to garlic a major problem is the high variaton of bioactive compounds between different Echinacea preparations. Cranberries (Vaccinium macrocarpon) for urinary tract infections [44, 45], mistletoe (Viscum album) for cancer [46–48], peppermint (Mentha piperita) oil for irritable bowel syndromes [49, 50] and saw palmetto (Serenoa repens) for benign prostate hyperplasia [51–53] have each been subject to two reviews. For saw palmetto there is good evidence for efficacy over placebo while for the other three the data are inconclusive (see table 3).

Single systematic reviews have been published on aloe (Aloe vera) [54], artichoke (Cynara scolymus) leave extract [55], evening primrose (Oenothera biennis) oil [56], feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium) [57], ginger (Zingiber officinialis) [58], ginseng (Panax ginseng) [59], horse chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum) seeds [60], kava (Piper methysticum) [61], milk thistle (Silybum marianum) [62], a fixed combination of three herbal extracts [63], rye-grass pollen (Secale cereale) extract [64, 65], tea tree (Melaleuca alternafolia) oil [66], and valerian (Valehana officinalis) root [67] (see table 4). The only review which focused on a herbal intervention which is not marketed as a drug or food supplement was on cabbage leaves for breast engorgement and included a single small-scale trial [68]. Chinese herbal therapy for atopic eczema [69] and a variety of herbs for lowering blood glucose [70] and for analgesic and anti-inflammatory purposes [71] have also been reviewed. For some of these herbal preparations the evidence is promising but further studies are considered necessary to establish efficacy in almost every case.

Discussion

Our overview shows that a considerable number of systematic reviews on herbal medicines is available. In the majority of cases the reviewers considered the available evidence as promising but only very rarely as convincing and sufficient as a firm basis for clinical decisions. The methodological quality of the primary studies has been criticized by many reviewers.

Our summary of the existing studies must be interpreted with caution. What we performed is a systematic review of systematic reviews which inherently bears a large risk of oversimplification. Readers who want to reliably assess the evidence for a given herb for a defined condition should read the respective reviews. Our collection – which to the best of our knowledge is complete up to summer 2000 – is aimed at facilitating the access and giving an idea of the amount of the available evidence. Based on the increase of herbal medicine reviews in recent years we expect that at least ten new publications will become available in the year 2001.

Most of the currently available systematic reviews address herbal preparations which are marketed and widely used in industrialized countries. However, the widespread traditional use of herbs in the Third World is rarely ever investigated and has not been subjected to systematic reviews. The many herbs used in folk medicine or other traditional uses of herbs (for example, hypericum is used for a variety of ailments other than depression including enuresis, diarrhoea, gastritis, bronchitis, asthma, sleeping disorders etc.) seem to be rarely investigated. Furthermore, practitioners of herbal medicine often combine different herbs and use unconventional diagnostic approaches to adapt prescriptions to single patients. It seems likely that these traditional forms of herbal medicine will remain underresearched relative to single herbal preparations due to the lack of financial incentive for sponsors and due to methodological problems.

Herbal medicines products are not, in general, subject to patent protection. This reduces the motivation for drug companies to invest in trials. Many of the existing herbal medicine manufacturers are comparably small companies, often with limited research resources and expertise. Maybe partly for these reasons, the quality of many older herbal medicine trials is low. Furthermore, negative trials which could threaten the company's survival might not become published.

A fundamental problem in all clinical research of herbal medicines is whether different products, extracts, or even different lots of the same extract are comparable and equivalent. This is a major issue in the expert research community and a major obstacle to a reliable assessment for the non-expert. For example, Echinacea products can contain other plant extracts, use different plant species (E. purpurea, pallida or angustifolia), different parts (herb, root, both), and might have been produced in quite different manners (hydro- or lipophilic extraction). Pooling studies that use different herbal products in a quantitative meta- analysis can be misleading. Health care professionals and patients considering to prescribe or take a particluar herbal product should check carefully whether the respective product or extract has been tested in the trials included in a review. On the health food store shelf the high quality, standardized products used in the trials might not be available. Only a herbal medicine expert can judge with some certainty whether the results can be extrapolated to the product of interest.

On the level of health care policies the available systematic reviews more often provide insight into the deficiencies of the evidence than guidance for decision making. Trials on hard endpoints are very rarely available and observation periods have generally been short. The clinical relevance of the observed effects is not always clear.

Herbal medicines are generally considered as comparably safe. While this is probably correct case reports show that severe side effects and relevant interactions with other drugs can occur. For example, hypericum extracts cause considerably fewer side effects than tricyclic antidepressants [92] but can decrease the concentration of a variety of other drugs by enzyme induction [93]. Several reviews summarizing side effects and interactions have been published [94–98].

In conclusion, the systematic reviews collected for this analysis are a good tool to get an overview of the available evidence from clinical trials in the area of herbal medicine. However, applying the findings to patients care is problematic for those who are not experts in herbal medicine. In this case it might be better to directly search the literature for clinical trials of the respective product.

References

Vickers A, Zollman CE: ABC of complementary medicine: herbal medicine. BMJ. 1999, 319: 1050-1053.

Schwabe U: Arzneimittel der besonderen Therapierichtungen (Naturheilmittel). In Arzneiverordnungs-Report 1998. Edited by Schwabe U, Paffrath D. Berlin: Springer,. 1999, 621-656.

Brevoort P: The booming US botanical market. A new overview. HerbalGram. 1998, 44: 33-51.

Barnes J: Phytotherapy: consumer and pharmacist perspectives. In: Herbal medicine – a concise overview for professionals. Edited by Ernst E. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann,. 2000, 19-33.

Bodeker GC: Editorial. J Altem Complement Med. 1996, 3: 323-326.

Linde K, Vickers A, Hondras M: Systematic reviews of complementary therapies – an annotated bibliography. Part 1: acupuncture. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2001, 1: 3-10.1186/1472-6882-1-3.

Pittler MH, Ernst E: Ginkgo biloba extract for the treatment of intermittent claudication: a meta- analysis of randomized trials. Am J Med. 2000, 108: 276-281. 10.1016/S0002-9343(99)00454-4.

Moher D, Pham B, Ausejo M, Saenz A, Hood S, Barber GG: Pharmacological management of intermittent claudication: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Drugs. 2000, 59: 1057-1070.

Ernst E: Ginkgo biloba in der Behandlung der Claudicatio intermittens. Fortschr Med. 1996, 114: 85-87.

Schneider B: Ginkgo-biloba-Extrakt bei peripheren arteriellen Verschlusskrankheiten. Meta Analyse von kontrollierten klinischen Studien. Arzneim-Forsch/Drug Res. 1992, 42(1): 428-436.

Letzel H, Schoop W: Gingko-biloba-Extrakt EGb 761 und Pentoxifyllin bei Claudicatio intermittens. Sekundäranalyse zur klinischen Wirksamkeit. VASA. 1992, 21: 403-410.

Kleijnen J, Knipschild P: Gingko biloba for intermittent claudication and cerebral insufficiency. In: Kleijnen J. Food supplements and their efficacy. Maastricht: Rijksuniversiteit Limburg,. 1991, 83-94.

Weiss G, Kallischnigg G: Gingko-biloba-Extrakt (EGb 761) – Meta-Analyse von Studien zum Nachweis der therapeutischen Wirksamkeit bei Hirnleistungsstorungen bzw. peripherer arterieller Verschlusskrankheit. Muench med Wschr. 1991, 10: 138-142.

Ernst E, Pittler MH: Ginkgo biloba for dementia: a systematic review of double-blind, placebo- controlled trials. Clin Drug Invest. 1999, 17: 301-308.

Oken BS, Storzbach DM, Kaye JA: The efficacy of ginkgo biloba on cognitive function in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 1998, 55: 1409-1415. 10.1001/archneur.55.11.1409.

Hopfenmuller W: Nachweis der therapeutischen Wirksamkeit eines Ginkgo biloba-Spezialextraktes – Meta-Analyse von 11 klinischen Studien mit Patienten mit Hirnleistungsstörungen im Alter. Arzneim-Forsch /Drug Res. 1994, 44(ll): 1005-1013.

Kleijnen J, Knipschild P: Gingko biloba for cerebral insufficiency. Br J din Pharmacol. 1992, 34: 352-358.

Ernst E, Stevinson C: Ginkgo biloba for tinnitus: a review. Clin Otolaryngol. 1999, 24: 164-167. 10.1046/j.1365-2273.1999.00243.x.

Evans JR: Ginkgo biloba extract for age-related macular degeneration (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 1. 2000, . Oxford: Update Software.

Gaster B: St John's wort for depression. A systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2000, 160: 152-156. 10.1001/archinte.160.2.152.

Williams JW, Mulrow CD, Chiquette E, Hitchcock Noel P, Aguilar C, Cornell J: A systematic review of newer pharmacotherapies for depression in adults: Evidence report summary. Ann Int Med. 2000, 132: 743-756.

Mulrow CD, Williams JW, Trivedi M: Treatment of depression – newer pharmacotherapies. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1998, 34: 409-795.

Kim HL, Streltzer J, Goebert D: St. John's wort for depression: A meta-analysis of well-defined clinical trials. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999, 187: 532-539. 10.1097/00005053-199909000-00002.

Stevinson C, Ernst E: Hypericum for depression. An update of the clinical evidence. Neuropsychopharmacol. 1999, 9: 501-505. 10.1016/S0924-977X(99)00032-2.

Linde K, Mulrow CD: St John's wort for depression (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 4. 1998, . Oxford: Update Software.

Linde K, Ramirez G, Mulrow CD, Pauls A, Weidenhammer W, Melchart D: St John's wort for depression – an overview and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. BMJ. 1996, 313: 253-258.

Volz HP: Controlled clinical trials of hypericum extract in depressed patients – an overview. Pharmacopsychiat. 1997, 30 (suppl): 72-75.

Ernst E: St. John's Wort, an anti-depressant? A systematic, criteria-based review. Phytomedicine. 1995, 2: 67-71.

Volz HP, Laux P: Potential treatment for subthreshold and mild depression: A comparison of St. John's wort extracts and fluoxetine. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2000, 41 (suppl 1): 133-137.

Friede M, Wüstenberg P: Johanniskraut zur Therapie von Angstsyndromen bei depressiven Verstimmungen. Ztschr Phytother. 1998, 19: 309-317.

Lawrence V, Mulrow C, Ackerman R: Garlic: Effects on cardiovascular risks and disease, protective effects against cancer, and clinical adverse effects. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment: Number 20. 2000, [http://www.ahcpr.gov/clinic/garlicsum.htm]

Stevinson C, Pittler MH, Ernst E: Garlic for treating hypercholesterinemia – a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Ann Intern Med. 2000, 133: 420-429.

Silagy C, Neil A: Garlic as a lipid lowering agent – a meta-analysis. J Roy Coll Phys. 1994, 28: 39-45.

Neil HAW, Silagy CA, Lancaster : Garlic powder in the treatment of moderate hyperlipidaemia: a controlled trial and meta-analysis. J Roy Coll Pract London. 1996, 30: 329-334.

Warshafsky S, Kamer RS, Sivak SL: Effect of garlic on total serum cholesterol. Ann Int Med. 1993, 119: 599-605.

Silagy CA, Neil HA: A meta-analysis of the effect of garlic on blood pressure. J Hypertension. 1994, 12: 463-468.

Kleijnen J: Controlled clinical trials in humans on the effects of garlic supplements. In: Kleijnen J. Food supplements and their efficacy. Maastricht: Rijksuniversiteit Limburg,. 1991, 73-82.

Kleijnen J, Knipschild P, ter Riet G: Garlic, onions and cardiovascular risk factors. A review of the evidence from human experiments with emphasis on commercially available preparations. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1989, 28: 535-544.

Jepson RG, Kleijnen J, Leng GC: Garlic for lower limb atherosclerosis (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 4. 1998, . Oxford: Update Software.

Barrett B, Vohmann M, Calabrese C: Echinacea for upper respiratory tract infection. J Fam Pract. 1999, 48: 628-635.

Melchart D, Linde K, Fischer P, Kaesmayr J: Echinacea for prevention and treatment of the common cold (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 1. 1999, . Oxford: Update Software.

Melchart D, Linde K, Worku F, Bauer R, Wagner H: Immunmodulation mit Echinacea-haltigen Arzneimittein – eine kriteriengestützte Analyse der kontrollierten klinischen Studien. Forsch Komplementärmed. 1994, 1: 26-36.

Melchart D, Linde K, Worku F, Bauer R, Wagner H: Immunomodulation with Echinacea – a systematic review of controlled clinical trials. Phytomedicine. 1994, 1: 245-254.

Jepson RG, Mihaljevic L, Craig J: Cranberries for the prevention of urinary tract infections (Cochrane Review). In The Cochrane Library, Issue 4. 1998, . Oxford: Update Software.

Jepson RG, Mihaljevic L, Craig J: Cranberries for the treatment of urinary tract infections (Cochrane Review). In The Cochrane Library, Issue 4. 1998, . Oxford: Update Software.

Kleijnen J, Knipschild P: Mistletoe treatment for cancer. Review of controlled trials in humans. Phytomedicine. 1994, 1: 255-260.

Kiene H: Klinische Studien zur Misteltherapie karzinomatöser Erkrankungen. Therapeutikon. 1989, 6: 347-353.

Kiene H: Klinische Studien zur Misteltherapie der Krebserkrankung. Eine kritische Würdigung. Herdecke: Dissertation,. 1989

Jailwala J, Imperiale TF, Kroenke K: Pharmacologic treatment of the irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med. 2000, 133: 136-147.

Pittler MH, Ernst E: Peppermint oil for irritable bowel syndrome: a critical review and meta- analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998, 93: 1131-1135. 10.1016/S0002-9270(98)00224-X.

Boyle P, Robertson C, Lowe F, Roehborn C: Meta-analysis of clinical trials of Permixon in the treatment of symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 2000, 55: 533-539. 10.1016/S0090-4295(99)00593-2.

Wilt TJ, Ishani A, MacDonald R, Stark G, Mulrow C, Lau J: Serenoa repens for treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 1. 2000, . Oxford: Update Software.

Wilt TJ, Ishani A, Stark G, MacDonald R, Lau J, Mulrow C: Saw palmetto extracts for treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia – a systematic review. JAMA. 1998, 280: 1604-1609. 10.1001/jama.280.18.1604.

Vogler BK, Ernst E: Aloe vera: A systematic review of its clinical effectiveness. Br J Gen Pract. 1999, 49: 823-828.

Pittler MH, Ernst E: Artichoke leaf extract for serum cholesterol reduction. Perfusion. 1998, 11: 338-340.

Morse PF, Horrobin DF, Manku MS: Meta-analysis of placebo-controlled studies of the efficacy of Epogam in the treatment of atopic eczema. Relationship between plasma essential fatty acid changes and responses. Br J Dermatol. 1989, 121: 75-90.

Vogler BK, Pittler MH, Ernst E: Feverfew as a preventive treatment for migraine: a systematic review. Cephalalgia. 1998, 18: 704-708. 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1998.1810704.x.

Ernst E, Pittler MH: Efficacy of ginger for nausea and vomiting: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Intern J Anesth. 2000, 84: 367-371.

Vogler BK, Pittler MH, Ernst E: The efficacy of ginseng. A systematic review of randomised clinical trials. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1999, 55: 567-575. 10.1007/s002280050674.

Pittler MH, Ernst E: Horse-chestnut seed extract for chronic venous insufficiency. Arch Dermatol. 1998, 134: 1356-1360. 10.1001/archderm.134.11.1356.

Pittler MH, Ernst E: Efficacy of kava extract for treating anxiety: systematic review and meta- analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000, 20: 84-89. 10.1097/00004714-200002000-00014.

Lawrence V, Mulrow C, Jacobs B: Report on milk thistle: Effects on liver disease and cirrhosis and clinical adverse effects. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment: Number 21. [http://www.ahcpr.gov/clinic/milktsum.htm]

Ernst E: The efficacy of Phytodolor for the treatment of musculoskeletal pain – a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Natural Medicine Journal. 1999, Summer: 14-7.

MacDonald R, Ishani A, Rutks I, Wilt TJ: A systematic review of Cernilton for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Br J Urol Int. 2000, 85: 836-841. 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00365.x.

Wilt TJ, MacDonald R, Ishani A, Rutks I, Stark G: Cernilton for benign prostatic hyperplasia (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 2. 2000, . Oxford: Update Software.

Ernst E, Huntley A: Tea tree oil: a systematic review of randomised clinical trials. Forsch Komplementärmed. 2000, 7: 17-20. 10.1159/000057164.

Stevinson C, Ernst E: Valerian for insomnia: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Medicine. 2000, 1: 91-99. 10.1016/S1389-9457(99)00015-5.

Renfrew MJ, Lang S: Do cabbage leaves prevent breast engorgement? (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 4. 1998, . Oxford: Update Software.

Armstrong NC, Ernst E: The treatment of eczema with Chinese herbs: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1999, 48: 262-264. 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00004.x.

Ernst E: Plants with hypoglycaemic activity in humans. Phytomedicine. 1997, 4: 73-78.

Ernst E, Chrubasik S: Phyto-anti-inflammatories: a systematic review of randomized, placebo- controlled, double-blind trials. Rheum Dis Clin North America. 2000, 26: 13-27.

Budeiri D, Li Wan Po A, Dornan JC: Is Evening Primrose Oil of value in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome?. Controlled Clin Trials. 1996, 17: 60-68. 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00082-8.

Diehm C: The role of oedema protective drugs in the treatment of venous insufficiency: a review of evidence based on placebo-controlled clinical trials with regard to efficacy and tolerance. Phlebology. 1996, 11: 23-29.

Evans MF, Morgenstern K: St. John's wort: an herbal remedy for depression?. Canadian Family Physician. 1997, 43: 1735-1736.

Giles JT, Palat CR, Chien SH, Chang ZG, Kennedy DT: Evaluation of echinacea for treatment of the common cold. Pharmacotherapy. 2000, 20: 690-697.

Josey ES, Tackett RL: St. John's wort: a new alternative for depression?. Intern J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1999, 37: 111-119.

Kleijnen J, ter Riet G, Knipschild P: Teunisbloemolie. Een overzichtvan gecontroleerd onderzoek. Pharmaceutisch Weekblad. 1989, 124: 418-423.

Knipschild P: Ginseng: pep of nep?. Pharmaceutisch Weekblad. 1988, 123: 4-11.

McPartland JM, Pruitt PL: Medical marijuana and its use by the immunocompromised. Altern Ther Health Med. 1997, 3: 39-45.

Weihmayr T, Ernst E: Die therapeutische Wirksamkeit von Crataegus. Fortschr Med. 1996, 114: 27-29.

Wettstein A: Cholinesterase inhibitors and ginkgo extracts – are they comparable in the treatment of dementia? Comparison of published placebo-controlled efficacy studies of at least six months duration. Phytomed. 2000, 6: 393-401.

Wong AHC, Smith M, Boon HS: Herbal remedies in psychiatric practice. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998, 55: 1033-1044. 10.1001/archpsyc.55.11.1033.

Ernst E, Pittler MH: Yohimbine for erectile dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Urol. 1998, 159: 433-436.

Mclntosh HM, Olliaro P: Artemisin derivatives for treating uncomplicated malaria (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 2. 2000, . Oxford: Update Software.

Mclntosh HM, Olliaro P: Artemisin derivatives for treating severe malaria (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 2. 2000, . Oxford: Update Software.

Pittler MH, Ernst E: Artemether for severe malaria: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Clin Infect Dis. 1999, 28: 597-601.

Wilt TJ, Ishani A, MacDonald R, Stark G, Mulrow C, Lau J: Beta-sitosterols for benign prostatic hyperplasia (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 1. 2000, . Oxford: Update Software.

Dumont L, Mardirosoff C, Tramér M: Efficacy and harm of pharmacological prevention of acute mountain sickness: a quantiative systematic review. BMJ. 2000, 321: 267-272. 10.1136/bmj.321.7256.267.

Ernst E: Can allium vegetables prevent cancer?. Phytomed. 1997, 4: 79-83.

Joy CB, Mumby-Croft R, Joy LA: Polyunsaturated fatty acid (fish or evening primrose oil) for schizophrenia (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 2. 2000, . Oxford: Update Software.

Young GL, Jewell MD: Creams to prevent striae gravidarum (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 4. 1998, . Oxford: Update Software.

Ernst E, Rand Jl, Barnes J, Stevinson C: Adverse effects profile of the herbal antidepressant St. John's wort (Hypericum perforatum L.). Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1998, 54: 589-594. 10.1007/s002280050519.

Ernst E: Second thoughts about safety of St John's wort. Lancet. 1999, 354: 2014-2015. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)00418-3.

De Smet PAGM: Health risks of herbal remedies. Drug Safety. 1995, 13: 81-93.

Miller LG: Herbal medicine. Selected clinical considerations focusing on known or potential drug- herb interactions. Arch Intern Med. 1998, 158: 2200-2211. 10.1001/archinte.158.20.2200.

Fugh-Berman A: Herb-drug interactions. Lancet. 2000, 355: 134-138. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)06457-0.

Ernst E: Possible interactions between synthetic and herbal medicinal products. Part 1: a systematic review of the indirect evidence. Perfusion. 2000, 13: 4-15.

Ernst E: Possible interactions between synthetic and herbal medicinal products. Part 2: a systematic review of the direct evidence. Perfusion. 2000, 13: 60-70.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/backmatter/1472-6882-1-5-b1.pdf

Acknowledgements

KL's work was partly funded by the NIAMS grant 5 U24-AR-43346-02 and by the Carl and Veronica Carstens Foundation, Essen, Germany. We would like to thank Brian Berman for his support, his help to get funding and his patience in awaiting the completion of our work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interest

KL, DM, GtR, and AV have been involved in some of the reviews analyzed. These were extracted and assessed by other members of the team.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Linde, K., ter Riet, G., Hondras, M. et al. Systematic reviews of complementary therapies – an annotated bibliography. Part 2: Herbal medicine. BMC Complement Altern Med 1, 5 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-1-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-1-5