Abstract

Background

Wife beating is an important public health problem in many developing countries. We assessed the rates of wife beating and examined factors associated with wife beating in 1995 and 2005 in Egypt.

Methods

We used data from two Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) conducted in Egypt in 1995 and 2005 using multistage household sampling. Data related to wife beating included information from 7122 women in 1995 and 5612 women in 2005. Logistic regression was used to analyze factors independently associated with wife beating. Special weights were used to obtain nationally representative estimates.

Results

In 1995 17.5% of married women in Egypt experienced wife beating in the last 12 months, in 2005 – 18.9% or 16.0%, using different measures. The association between socio-demographic differentials and wife beating was weaker in the newer survey. The 12-month prevalence of wife beating was lower only when both partners were educated, but the differences across education levels were less pronounced in 2005. Based on the information available in the 2005 survey, more educated women experienced less severe forms of wife beating than less educated women.

Conclusion

Different measures used in both surveys make a direct comparison difficult. The observed patterns indicate that the changes in prevalence may be masked by two opposite processes occurring in the society: a decrease in (severe forms of) wife beating and an increase in reporting of wife beating. Improving the access to education for women and raising education levels in the whole society may help reducing wife beating.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Intimate partner violence is a worldwide problem, present in all cultures and societies [1]. The rates of wife beating are higher among young couples, in poor and less educated, but beating occurs in all socio-economic groups and also across more mature couples [2, 3]. The prevalence of wife abuse and battering has been studied extensively in many societies including Arabic countries [4–7]. Consistent with the high acceptance of wife beating, surveys in Egypt, Palestine, and Tunisia indicated a very high prevalence of wife beating in these countries [8]. Egypt is a country with both a high prevalence of wife beating compared to other countries [9, 10] and an exceptionally high level of approval regarding the husbands' right to wife beating [11, 12]. For instance, almost 9 in 10 ever-married women accept at least one reason for wife beating in Egypt [12]. Many activities to educate women and improve the situation in Egypt, including an increased availability of shelters may have affected the attitude towards the acceptability of beating [13]. Also a new divorce law was introduced in 2000 [14]. While this law still makes the divorce difficult, it was an improvement towards previous status.

Two Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) conducted 10 years apart (in 1995 and 2005) in Egypt obtained information about wife beating [11, 15]. In these two surveys different methodologies were used to assess wife beating. In 1995, DHS introduced for the first time a module assessing the status of woman in the country including a single non-standardized question on wife beating [9]. This was the first attempt to collect information on wife beating in the history of DHS. In 2005, a standardized approach of measuring wife beating was used, which is based on 8 items describing different forms of violence. While comparing the information collected in the surveys three different underlying mechanisms of the observed difference should be considered: an impact of the different way the question was asked, a change in prevalence of wife beating over time and/or a change in reporting of wife beating. We use the data of these surveys to a) assess the rates of wife beating in 1995 and 2005, and b) examine factors associated with wife beating in the two surveys. Additionally, we assess more in depth the association between education of both partners and the patterns of violence.

Methods

Sample

Several DHS were conducted in Egypt, but only two of them investigated issues surrounding wife beating: the surveys conducted in 1995 and 2005 (further: EDHS-1995 and EDHS-2005). Both EDHS were nationally representative household surveys applying multistage sampling technique [11, 15]. DHS's all over the world apply a standard questionnaire with several modules covering information about reproductive health of women such as contraceptive knowledge and use, fertility preferences and attitudes about family planning, pregnancy outcomes, breastfeeding and socio-economic characteristics [16]. EDHS-1995 was started in January 1995 and finished in December 1995. EDHS-2005 lasted from February to July 2005. Both surveys conducted household interviews using standardized questionnaire in Arabic language. In both survey the response rates were very high (about 99%). In EDHS-1995 an additional module was included to collect information regarding the women's status in households, including information about wife beating. This was done in one-third of all households selected for EDHS-1995 (n = 7122). The module was used for the first time in Egypt by DHS [9]. In EDHS-2005 information about wife beating was obtained for a randomly selected subsample for the anaemia testing (n = 5612). The 2005 survey used standardized questions based on guidelines from the World Health Organization and were first implemented in the DHS in Nicaragua in 1998 [9].

Outcome variables

The outcome variable in our analysis: beaten by husband in the last 12 months (yes/no) was created from several questions, asked in slightly different ways in the two surveys. In EDHS-1995 the questions were "From the time you were married has anyone ever beaten you?", "Can you tell me who has done this to you since you were married?" and "Approximately, how many times were you beaten [by this person] in the past one year?". Women who answered positively on the first question, named their husband as the person doing the beating in the second question, and reported being beaten by husband once or more in the last 12 months were classified into the "yes" group. All remaining women were classified as "no". In EDHS-2005 several questions regarding the type of beating were asked, namely "Does/did" your (last) husband ever push you, shake you, or throw something at you; slap you or twist your arm; punch you with his fist or with something that could hurt you; kick you or drag you; try to strangle you or burn you; threaten you with a knife, gun, or other type of weapon; attack you with a knife, gun, or other type of weapon; physically force you to have sexual intercourse with him when you did not want to?" and "How often did this happen during the last 12 months?". Women who gave a positive answer for any type of beating and reported that it happened once or more in the last 12 months were classified as "yes", all remaining women as "no" – this is used as standard definition in the further text. We also used a more restricted definition of wife beating in the 2005 survey, based only on 6 items: slap you or twist your arm; punch you with his fist or with something that could hurt you; kick you or drag you; try to strangle you or burn you; threaten you with a knife, gun, or other type of weapon; attack you with a knife, gun, or other type of weapon.

Socio-demographic variables

We analysed the association between several socio-demographic factors such as age, age at first marriage, place of residence (urban vs. rural), region, educational level of respondent and partner, religion, current working status and wife beating. We also included the variable blood relationship to husband (with two categories "yes" and "no") in the analysis, since beating occurs more frequently in partnerships with blood relationship [17]. The original variable consisted of seven categories for different degrees of blood relationship; any type of blood relationship was classified as yes.

Statistical analysis

Chi-square test was used to analyse bivariate associations between wife beating and the other variables. In a second step, all considered variables were included jointly in a multivariable logistic regression model for each survey separately. Prior to analysis we ruled out a multicollinearity between independent variables using methods described by Allison [18].

The simultaneous associations of the education of both spouses with the outcome were investigated in a separate analysis. The model included education of each of the spouses, interaction between them, the indicator variable coding the difference between both surveys and the interaction between education and the indicator variable. In this way we could investigate whether education of the other partner had a modifying effect and whether the effects of education and their interaction were different in the two survey rounds. This model was reduced by removing terms for which the Wald-test indicated no significance and from the final model the proportion of women experiencing wife beating was calculated for different education categories. For this analysis the four education categories for the respondent and her husband were each collapsed into two: low = no/primary education and high = secondary/higher education.

In the next step we aimed to classify women according to the kind of wife beating they are experiencing. Since the EDHS-2005 investigated 8 different types of wife beating and some of them were highly correlated, we performed first a factor analysis to find underlying patterns of violence. The obtained factors were used to define clusters of women experiencing different forms of violence. Then the association between forms of experienced violence and education level of the women was investigated.

In all analyses, special weights (included in the dataset) were used to obtain nationally representative estimates. Data analysis was performed using the statistical program SAS for Windows, version 9.1.

Results

Description of the sample

In general, some positive tendencies can be observed over the period of ten years between the two EDHS (Table 1): The education level of the women and their partners increased substantially; the percentage of women with no education decreased by 10 percent and the percentage of women with higher education increased by 4 percent. The same was observed for their partners; the percentage of men with no education decreased by 8 percent and the percentage of highly educated men increased by 4 percent. Smaller differences were observed for the current working status of women. The percentages of women with a very young age at marriage or at birth of their first child were substantially reduced. Also a considerably lower percentage of marriages between related individuals (with a blood relationship) was observed in the newer survey round.

12 month prevalence and factors associated with wife beating

The prevalence of wife beating in the last 12 months was 17.5% in 1995 and 18.9% in 2005, based on the single question in 1995 and all items used in 2005. When in the 2005 survey wife beating was defined only based on the items clearly referring to beating the resulting prevalence was 16%. The most frequent forms of wife beating were pushing and slapping (Table 2).

The bivariate analysis indicates that the proportion of beaten women was lower in urban regions than in rural in both survey years (Table 3, 2nd and 4th column). The proportion of women who experienced beating was considerably higher among women with no education compared to those with higher education in both surveys. The same trend was observed for partner's education. Wife beating decreased with age of the respondent, but was higher for women who married and had first birth at a young age.

In multivariable logistic regression, all differences between categories of the above mentioned variables in regard to wife beating were reduced (Table 3, 3rd and 5th column). The estimates for education in bivariate and multivariable analysis were similar for a woman's education but not for her partner's education. We observed minor differences when the analysis was repeated with the outcome variable based on restricted items (data not shown).

In regard to differences in factors between the two EDHS rounds associated with wife beating, we found significant results for the education of the partner, the interaction between a woman's and her partner's education, region of the country and age at first marriage (data not shown). In 2005 the decrease in wife beating with increasing level of partner's education was less pronounced. Similarly, the difference between regions was reduced as compared to 1995. In regard to the age at first marriage, the difference occurred only in the group marrying at age 30 plus years: such women had a reduced risk for wife beating in 1995 and increased risk in 2005. The analysis repeated with the outcome variable based on restricted items displayed only minor differences (data not shown).

When the effects of a woman's and her partner's education were both taken into account, the prevalence of wife beating was reduced only when both partners had secondary or higher education (Table 4). The extent of this reduction was lower in 2005 in comparison to 1995.

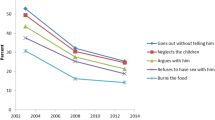

Patterns of violence

Factor analysis revealed three underlying forms of violence: extreme (items: strangled/burned, threatened with weapon, attacked with weapon), strong (items: kicked/dragged, punched) and moderate (items: pushed, slapped/twisted, not forced sexually). Women who experienced violence in the past 12 months clustered in four groups which can be defined by patterns of violence (Figure 1). The smallest group (2.3%) experienced extreme forms of violence; the largest group (52.5%) scored low on all three forms of violence; 18.6% experienced mainly moderate forms of violence and 26.6% experienced strong and moderate forms of violence.

Patterns of wife beating and proportion of women within clusters defined by these patterns in 2005 survey (only women who experienced wife beating within last 12 months) (on the y-axis score indicating average values of the given group relative to the remaining population – 0 is the median score in the total sample).

Discussion

Information from two DHS conducted 10 years apart in Egypt was evaluated to investigate the prevalence of and factors associated with wife beating. Despite the different measurements of wife beating in two surveys we found almost similar prevalence and patterns of risk factors in both surveys. This similarity can be resulting from an increased reporting due to a change in attitudes or because of a more detailed questioning in the newer survey, paralleling a true decrease in the prevalence between the surveys. Formally, the Arabic translation of the question used in the 1995 survey covered almost all items used in the 2005 questionnaire [19], and the most frequently in 2005 reported items would qualify as beating, but some items might be less obvious. We therefore conducted additional analyses with a more restricted selection of items for the outcome variable in 2005 survey, which resulted in only a slight change in the reported prevalence. Still, a more detailed question used in 2005 may have prompted higher reporting than the single question used in 1995. While we are not aware of any study directly comparing the two approaches used in DHS surveys with respect to reporting of violence, there is some evidence that asking about violence in different sections of the questionnaire, using different wording and multidimensional measures improves reporting of violence [20, 21]. While the issue of the extent of underreporting remains unresolved, there was also some indication of societal changes affecting the reporting of violence, which can be seen in the patterns of reporting and milder forms of violence experienced by better educated women. Differential reporting of violence across different characteristics of the respondents was observed in other studies [22] and additional dynamics can be introduced by changes in attitudes towards violence in the society.

Our analysis showed less pronounced risk factors associated with wife beating in the more recent EDHS and thus more homogeneity in wife beating across the strata of the population. This could be caused by a more general acceptance of wife beating in the population [12] or for example increased reporting of milder forms of violence in groups with lower prevalence.

When the education of both partners was evaluated jointly, it became clear that the woman's education made the difference with regard to wife beating. However, the rate of wife beating was reduced only when also the partner had secondary or higher education himself (the other case, when woman had a higher education than her partner, did not show a reduction in wife beating). Also the forms of wife beating differed by education level, a finding not reported from previous studies, but one that seems likely. A higher educational level of the respondent and her partner was found to be associated with a lower risk of violence also in the recent review by Jewkes [6]. On the contrary, most of the previous studies focused on education of the female partner only [23–26]. In a study in rural areas of Bangladesh, wife beating was reduced when women contributed economically to the household [23]. But the relationship between education of the women and wife beating is more complex: when women had a higher level of education than their partners, the levels of wife beating were higher in a study in Albania [27]. Communistic countries encouraged women's education, and women's rights were part of the political agenda [28]. In Turkey, women in higher education have career development perspectives which are partly better than in Western European countries [29]. But while dominant religion in Turkey is also Islam, there are strong cultural differences between Arabic Islamic countries and Turkey, and educated women might face more difficulties in Arabic Islamic countries [30]. Higher levels of violence experienced by educated women when their partner was less educated were also found in Kenya, with 50% of the population adhering to Islam [31]. In summary, it appears that raising education levels in the whole society, both men and women, is needed to reduce violence. When solely men are granted benefits of education, their violence behaviour might remain determined by patriarchal ideology and gender roles [32, 33].

Youngest age group showed highest odds ratios of wife beating in both surveys. This is consistent with the findings of another study in Egypt [34]. Younger women have also short duration of marriage and young age at marriage, both factors which can contribute to higher prevalence of violence. In contrary, there was no effect of woman's age on prevalence of violence as reported by men in a study in Bangladesh [35]. In Bangladesh the prevalence of physical violence in the last 12 months was between 60 and 70% across all age groups, which is substantially higher than in our analysis and suggests a higher cultural acceptance of violence. Women having fewer children (adjusted for age) had lower risk of being beaten in our analysis. This might indicate less traditional cultural background and thus lower acceptance of violence among these women. This finding is consistent with the findings of other studies in Bangladesh [35] and Mexico [36].

Conclusion

Beating by an intimate partner remains highly prevalent in Egypt, despite increasing levels of education in the population and initiatives to reduce wife beating. However, patterns of wife beating may have moved towards less severe forms in recent years. The woman's level of education appears a strong determinant of reduced wife beating, but only when her partner is also educated. Thus, improving women's access to education and raising levels of education in the whole society are promising strategies to reduce wife beating. Wife beating is all prevalent – not limited to selected risk groups – therefore interventions oriented towards the whole society rather than risk group oriented interventions are warranted. The concurrence of different trends and developments – like shifts in the level of education in the society or codes of behaviour within a social position – results in a very complex picture of societal changes. To allow an analysis of trends, studies should use the same and standardized instruments. Additionally, changes in reporting attitudes should be measured and potential changes in patterns of wife beating should be taken into consideration.

References

Heise L, Ellsberg M, Gottmoeller M: A global overview of gender-based violence. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002, 78 (Suppl 1): S5-14. 10.1016/S0020-7292(02)00038-3.

Hedin LW, Janson PO: Domestic violence during pregnancy. The prevalence of physical injuries, substance use, abortions and miscarriages. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000, 79: 625-630. 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2000.079008625.x.

Hedin LW: [Abuse of women is a public health problem. All female patients over the age of 14 should be part of a routine screening program]. Lakartidningen. 2002, 99: 2268-4.

Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts CH: Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence. Lancet. 2006, 368: 1260-1269. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69523-8.

Zink T, Jacobson CJ, Pabst S, Regan S, Fisher BS: A lifetime of intimate partner violence: coping strategies of older women. J Interpers Violence. 2006, 21: 634-651. 10.1177/0886260506286878.

Jewkes R: Intimate partner violence: causes and prevention. Lancet. 2002, 359: 1423-1429. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08357-5.

Haj-Yahia MM: The incidence of wife abuse and battering and some sociodemographic correlats as revealed by two national surveys in Palestinian society. Journal of Family Violence. 2000, 14: 347-374. 10.1023/A:1007554229592.

Douki S, Nacef F, Belhadj A, Bouasker A, Ghachem R: Violence against women in Arab and Islamic countries. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2003, 6: 165-171. 10.1007/s00737-003-0170-x.

Kishor S, Johnson K: Profiling Domestic Violence; A Multi-Country Study, 2004. Report. 2004, Calverton, Maryland, USA, ORC Macro, MEASURE DHS+

Ammar NH: Beyond the shadows: domestic spousal violence in a "democratizing" Egypt. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2006, 7: 244-259. 10.1177/1524838006292520.

El-Zanaty F, Hussein EM, Shawky GA, Way AA, Kishor S: Egypt Demographic and Health Survey 1995. Final Report. Report. 1996, Calverton, Maryland, USA, National Population Council (Egypt) and Macro International Inc

Boy A, Kulczycki A: What we know about intimate partner violence in the Middle East and North Africa. Violence Against Women. 2008, 14: 53-70. 10.1177/1077801207311860.

Benninger-Budel C: Implementation of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women by Egypt. 2001, Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women. 24th session, OMCT

Human Rights Watch: Divorced from Justice: Women's Unequal Access to Divorce in Egypt. Report. 2004, 16;8 (E).

El-Zanaty F, Way A: Egypt Demographic and Health Survey 2005. Final Report. Report. 2006, Cairo, Egypt, Ministry of Health and Population, National Population Council, El-Zanaty and Associates and ORC Macro

Measure DHS: Demographic and Health Surveys. 2006, Calverton, USA, Macro International

Aderibigbe YA: Violence in America: a survey of suicide linked to homicides. J Forensic Sci. 1997, 42: 662-665.

Allison PD: Logistic regression using the SAS system: theory and application. 2000, Cary, NC: SAS Institute, 2

Diop-Sidibe N, Campbell JC, Becker S: Domestic violence against women in Egypt–wife beating and health outcomes. Soc Sci Med. 2006, 62: 1260-1277. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.022.

Dekeseredy WS: Enhancing the quality of survey data on woman abuse. Examples from a national Canadian study. Violence Against Women. 1995, 1: 158-173. 10.1177/1077801295001002004.

Smith M: Enhancing the quality of survey data on violence against women: a feminist aproach. Gender&Society. 1994, 8: 109-127.

Ellsberg M, Heise L, Pena R, Agurto S, Winkvist A: Researching domestic violence against women: methodological and ethical considerations. Stud Fam Plann. 2001, 32: 1-16. 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2001.00001.x.

Bates LM, Schuler SR, Islam F, Islam K: Socioeconomic factors and processes associated with domestic violence in rural Bangladesh. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2004, 30: 190-199.

Karamagi CA, Tumwine JK, Tylleskar T, Heggenhougen K: Intimate partner violence against women in eastern Uganda: implications for HIV prevention. BMC Public Health. 2006, 6: 284-10.1186/1471-2458-6-284.

Koenig MA, Lutalo T, Zhao F, Nalugoda F, Wabwire-Mangen F, Kiwanuka N, et al: Domestic violence in rural Uganda: evidence from a community-based study. Bull World Health Organ. 2003, 81: 53-60.

Rickert VI, Wiemann CM, Harrykissoon SD, Berenson AB, Kolb E: The relationship among demographics, reproductive characteristics, and intimate partner violence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002, 187: 1002-1007. 10.1067/mob.2002.126649.

Burazeri G, Roshi E, Jewkes R, Jordan S, Bjegovic V, Laaser U: Factors associated with spousal physical violence in Albania: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2005, 331: 197-201. 10.1136/bmj.331.7510.197.

Mahon R, Williams F: Gender and State in Postcommunist Societies: Introduction. Social Polititcs (electronic citation). 2007, 14 (3): 281-283.

Lundberg IE, Ozen S, Gunes-Ayata A, Kaplan MJ: Women in academic rheumatology. Arthritis Rheum. 2005, 52: 697-706. 10.1002/art.20881.

Cwikel J, Lev-Wiesel R, Al-Krenawi A: The physical and psychosocial health of Bedouin Arab women in the Negev region of Israel. Violence Against Women. 2003, 9: 240-257. 10.1177/1077801202239008.

Lawoko S, Dalal K, Jiayou L, Jansson B: Social inequalities in intimate partner violence: a study of women in Kenya. Violence Vict. 2007, 22: 773-784. 10.1891/088667007782793101.

Haj-Yahia MM: Wife abuse and battering in the sociocultural context of Arab society. Fam Process. 2000, 39: 237-255. 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2000.39207.x.

Haj-Yahia MM: Can people's patriarchal ideology predict their beliefs about wife abuse? The case of Jordanian men. Journal of community psychology. 2005, 33: 545-567. 10.1002/jcop.20068.

Yount K: Resources, family organization and domestic violence against married women in Minya, Egypt. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005, 67: 579-596. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00155.x.

Aklimunnessa K, Khan M, Kabir M, Mori M: Prevalence and correlates of domestic violence by husbands against wives in Bangladesh: evidence from a national survey. Journal of Men'S Health and Gender. 2007, 4: 52-63. 10.1016/j.jmhg.2006.10.016.

Diaz-Olavarrieta C, Ellertson C, Paz F, de Leon SP, arcon-Segovia D: Prevalence of battering among 1780 outpatients at an internal medicine institution in Mexico. Soc Sci Med. 2002, 55: 1589-1602. 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00293-3.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6874/8/15/prepub

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the ORC, Macro International for providing us with the datasets from Egypt Demographic and Health Surveys 1995 and 2005. We also thank the reviewers for their extensive comments on the manuscript, which helped us to clarify several aspects.

Funding: The paper was prepared during a three months scholarship of SL at the University of Bielefeld, which was supported by an unrestricted educational grant from the Egyptian embassy in Germany.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

MKA performed the analysis and drafted the manuscript. RTM contributed to the development of the research question, supervised the analysis and wrote the final version of the manuscript. SL developed the idea of the analysis and provided comments on the manuscript. ED and MMHK contributed to the discussion section. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Manas K Akmatov, Rafael T Mikolajczyk contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Akmatov, M.K., Mikolajczyk, R.T., Labeeb, S. et al. Factors associated with wife beating in Egypt: Analysis of two surveys (1995 and 2005). BMC Women's Health 8, 15 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-8-15

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-8-15