Abstract

Background

Dysregulation of the human Transforming Acidic Coiled Coil (TACC) genes is thought to be important in the development and progression of multiple myeloma, breast and gastric cancer. Recent, large-scale genomic analysis and Serial Analysis of Gene Expression data suggest that TACC1 and TACC3 may also be involved in the etiology of ovarian tumors from both familial and sporadic cases. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the occurrence of alterations of these TACCs in ovarian cancer.

Methods

Detection and scoring of TACC1 and TACC3 expression was performed by immunohistochemical analysis of the T-BO-1 tissue/tumor microarray slide from the Cooperative Human Tissue Network, Tissue Array Research Program (TARP) of the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA. Tumors were categorized as either positive (greater than 10% of cells staining) or negative. Statistical analysis was performed using Fisher's exact test and p < 0.05 (single comparisons), and p < 0.02 (multiple comparisons) were considered to be significant. Transgenomics WAVE high performance liquid chromatography (dHPLC) was used to pre-screen the TACC3 gene in constitutional DNA from ovarian cancer patients and their unaffected relatives from 76 families from the Gilda Radner Familial Ovarian Cancer Registry. All variant patterns were then sequenced.

Results

This study demonstrated absence of at least one or both TACC proteins in 78.5% (51/65) of ovarian tumors tested, with TACC3 loss observed in 67.7% of tumors. The distribution pattern of expression of the two TACC proteins was different, with TACC3 loss being more common in serous papillary carcinoma compared with clear cell carcinomas, while TACC1 staining was less frequent in endometroid than in serous papillary tumor cores. In addition, we identified two constitutional mutations in the TACC3 gene in patients with ovarian cancer from the Gilda Radner Familial Ovarian Cancer Registry. These patients had previously tested negative for mutations in known ovarian cancer predisposing genes.

Conclusion

When combined, our data suggest that aberrations of TACC genes, and TACC3 in particular, underlie a significant proportion of ovarian cancers. Thus, TACC3 could be a hitherto unknown endogenous factor that contributes to ovarian tumorigenesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

It is apparent that for a normal cell to develop into a highly delocalized metastatic cancer, multiple genetic events are required to overcome the normal mechanisms that control the growth and development of healthy tissue. About 10% of ovarian cancer patients inherit a familial predisposition, and of those cases, only 35–50% can be attributed to the inheritance of defects in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 tumor suppressor genes [1, 2]. In addition, BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations are not directly involved in the initiation events leading to the development of sporadic tumors, indicating that additional, as yet unidentified genes must play a significant role in the etiology of both familial and sporadic ovarian cancer. In ovarian cancer, comparative genomic hybridization (CGH), multicolor spectral karyotyping (SKY), and loss of heterozygosity (LOH) studies have identified several regions of the genome that may contain novel genes involved in the development and progression of ovarian cancer [3–5]. These techniques have indicated that deletions or rearrangements of 4p16 and 8p11, the loci for TACC3 and TACC1 respectively, commonly occur in 40% of ovarian cancer cell lines and primary tumors from both familial and sporadic cases [3–5]. SAGE (Serial Analysis of Gene expression) analysis further suggests that TACC3 and TACC1 are downregulated in ovarian tumors and ovarian cancer cell lines [6]. Thus, based upon both the location of TACC1 and TACC3 in regions consistently associated with ovarian cancer [3, 5] and SAGE expression data [6], we have set out to determine the occurrence of alterations of these TACCs in ovarian cancer.

Methods

Serial Analysis of Gene Expression (SAGE)

The results of SAGE analysis of libraries generated by the method of Velculescu et al [7] were downloaded from the SAGEMAP section of the Gene Expression Omnibus website at the National Center for Biotechnology Information [6], and critically assessed for reliability to specifically predict expression of TACC3 and TACC1 in ovarian tissue and tumors. SAGE profiles used for TACC3 and TACC1 were [8] and [9], respectively.

Tissue and tumor microarrays

T-BO-1 and IMH-343 tissue and tumor microarray slides were obtained from the Cooperative Human Tissue Network, Tissue Array Research Program (TARP) of the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD, USA) and Imgenex Corporation (San Diego, CA, USA), respectively. Each of these microarrays contain normal tissues that are known to express TACC1 and TACC3 [10–12]. Clear cell carcinomas on the tissue/tumor slides, which cannot be graded using the World Health Organisation or FIGO systems [13], were classified as grade 3, as recommended by the NCCN practice guidelines [14].

Immunohistochemical staining

Immunohistochemical procedures were first optimized using formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded MCF7 and HT-29 cell lines prepared in our laboratory. Conditions were then further optimized using mixed normal/tumor human tissue microarrays (Imgenex Corporation).

Tumor microarrays were deparaffinized in three changes of xylene and rehydrated using graded alcohols at room temperature. Endogenous peroxidase was quenched with aqueous 3% H2O2 for 20 min. and washed with PBS-Tween20 (PBS/T). Antigen retrieval was performed with citrate buffer pH 6.0 by heating twice in a microwave for 10 min., and then cooling to room temperature for 15 min. Following a PBS/T wash, the slides were placed in a humidity chamber and 0.03% w/v casein in PBS/T was applied to the tissue sections for 30 min. to block non-specific binding. This was then replaced with the primary anti-TACC3 antibody (#sc5885, Santa Cruz Biotech., Santa Cruz, CA, USA) at 1 μg/ml and left overnight at 4°C. As a negative control, a duplicate slide was incubated with antibody that had been precompeted with 10-fold excess of TACC3 peptide competitor [Santa Cruz #sc5885P] for 2 hr. at room temperature prior to use. The slides were then washed with PBS/T, followed by the biotinylated secondary antibody [Santa Cruz #sc2042 Donkey anti-goat] for 30 min. A PBS/T wash was followed by incubation with streptavidin-peroxidase reagent [#50-242, Zymed, Carlsbad, CA, USA] for 30 min. PBS/T was used as a wash and then chromogen DAB [#K3466, DAKO, Carpinteria, CA, USA] was applied for 5 min. (color reaction product – brown). The slides were then counterstained with Hematoxylin (blue in figures), dehydrated, cleared and finally coverslipped.

Antigen retrieval for TACC1 was essentially as described above. Slides were then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary anti-TACC1 antibody (#07-229, Upstate, Lake Placid, NY, USA) at 1 μg/ml. Concentration matched rabbit IgG (1 μg/ml) was used on a duplicate slide, instead of the primary TACC1 antibody, as a negative control for immunostaining. The slides were then placed on a DAKO autostainer with the following program; 1) one PBS/T wash; 2) incubation with a biotinylated secondary antibody [Vector Elite kit] for 30 min.; 3) one PBS/T wash; and then 4) incubation with ABC reagent [Vector Elite kit] for 30 min. PBS/T was used as a final wash and chromogen-DAB [DAKO] was applied for 5 min. (color reaction product – brown). The slides were then counterstained with Hematoxylin and dehydrated, cleared and coverslipped.

Image analysis

Tumor microarrays were examined by light microscopy and cores were categorized into either positive (+) or negative (-) staining for TACC3 and TACC1, with (+) staining representing those cores where greater than 10% of the cells had detectable staining, otherwise they were scored (-). No staining was observed in the negative controls, which were serial tumor microarray slides that were incubated with either peptide block or IgG depending upon the test antibody. Positive controls were normal tissues on each tissue and tumor array, and normal ovarian surface epithelium. Images were captured using a Nikon eclipse E600 microscope with Spot insight digital camera and Spot Advanced software version 4.0.1 (Diagnostic Instruments, MI, USA).

Statistical analysis

Fisher's exact test was performed using GraphPad Prism Version 3.03, (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA, http://www.graphpad.com). All tests were two-sided and p < 0.05 and p < 0.02 were considered to be significant for single and multiple comparisons respectively.

Mutation analysis using Transgenomic WAVE dHPLC

The TACC3 gene was screened for mutations using the Transgenomic WAVE dHPLC system [15]. The sequence of each fragment to be amplified by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was first analyzed using the WAVE melting profile software program to determine gradient and column temperature conditions for each PCR product. Individual exons and intronic regions encompassing the 5' and 3' splice sites were then amplified from a standard commercial normal human placental DNA sample (conditions and primer sequences available on request). These PCR products were then used to establish the actual melting profiles for each exon. Test samples were mixed with the standard normal control PCR product at a 1:1 ratio and denatured at 95°C for 5 min., followed by slow cooling to room temperature at the rate of 0.1°C every four seconds to enhance heteroduplex formation. WAVE dHPLC analysis was then performed and patterns compared with matched normal sibling controls (non-symptomatic) and the unmixed normal control pattern. For all variant patterns detected, aliquots from the original PCR reaction were then directly sequenced by the Roswell Park Cancer Institute Biopolymer core facility. Variant sequences were cross-referenced against GenBANK and Single Nucleotide Polymorphism databases [16], to test for occurrence in a wider population sample. New gene alterations that were found only in cDNAs from normal tissues in the databases, or found in normal and affected individuals in our test subjects were labelled as polymorphisms.

All investigations were performed after approval by the Roswell Park Cancer Institute institutional review board.

Results

Expression analysis of TACC1 and TACC3 in ovarian tumors

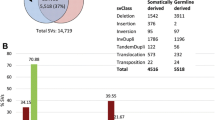

TACC1 and TACC3 are expressed in the epithelia of a number of different tissues, including the mammary gland and the ovary [17–19] (Fig. 1), suggesting that these proteins may be required for the normal maintenance of the epithelial component of organs within the body. Published SAGE (Serial Analysis of Gene Expression) analysis suggests that TACC1 expression is absent in 3 out of 7 bulk ovarian tumors and cell lines (Figure 3). Furthermore, TACC3 is downregulated in all 7 of the bulk ovarian tumors and tumor cell lines, compared with the normal human ovarian surface epithelium (HOSE) (Figure 3) [6]. Notably, similar to the two transciption factors GATA4 and GATA6 [20], TACC3 downregulation occurs in IOSE29, an immortalized ovarian surface epithelial cell line, suggesting that loss of TACC3 expression may be an early event during the immortalization process. To determine whether the pattern of gene expression noted by SAGE analysis is also evident in patient tumors, we assessed ovarian tumor microarrays from the National Cancer Institute multi-tumor tissue microarray (TARP) facility for expression of both proteins. 65 of the 75 OSE tumors on the tissue/tumor microarray could be evaluated for both TACC1 and TACC3 expression after the immunostaining procedure. Representative images demonstrating positive or negative tumor staining compared to normal human ovarian surface epithelium are shown in Fig. 1. A total of 21 (32.3%) and 41 (63.1%) showed positive staining for TACC3 and TACC1 respectively (Table 1). Thus, 44 (67.7%) and 24 (36.9%) could be categorized as absent or minimal expression for TACC3 and TACC1 respectively, similar to the results observed in the SAGE analysis. In addition, the allocation of TACC1 and TACC3 status to each core showed that 78.5% of the tumors exhibited negative immunoreactivity for one or both proteins. Within the ovarian tumor set tested (n = 65), there was a significant difference in the expression of TACC1 compared to TACC3 (Fisher's exact test, p = 0.0008) (Fig. 2). Expression of neither protein was associated with tumor grade. In all cases where TACC3 expression was observed, the protein was excluded from the nucleus (Fig. 1), contrary to the predominantly nuclear localization observed in the normal ovarian surface epithelium in vivo [17–19] (Fig 1). These results indicate that tumors derived from the ovarian surface epithelium exhibit low/negative expression or aberrant localization of TACC3, which may biologically contribute to development of these tumors.

Immunohistochemical analysis of tumor micoarrays. Representative normal human ovarian surface epithelium and tumor cores stained for TACC1 (panels A-E), and TACC3 (panels F-J) proteins to show positive and negative staining. TACC protein expression is detected as a brown signal against the blue Hematoxylin counterstain. In all cases where TACC3 expression was observed, the protein was excluded from the nucleus of the ovarian tumor cells, unlike the observable nuclear and cytoplasmic expression of TACC1. A, normal ovarian surface epithelium with nuclear/cytoplasmic TACC1 staining; B, serous papillary TACC1 +ve; C, serous papillary TACC1 -ve; D, endometroid TACC1 +ve; E, endometroid TACC1 -ve; F, normal ovarian surface epithelium with nuclear TACC3 staining; G, serous papillary TACC3 +ve; H, serous papillary TACC3 -ve; I, clear cell TACC3 +ve; J, clear cell TACC3 -ve. A-H: Main panel original magnification ×40; insets show whole tumor core at original magnification ×10.

Next, we examined the association of expression of each TACC protein with specific types of tumor to test whether the distribution of each TACC varied between subtypes (Summarized in Table 1). TACC3 expression was observed in 21.4% (9 of 42) serous papillary, 40% (2 of 5) mucinous, 42.8% (3 of 7) endometroid, and 63.6% (7 of 11) clear cell ovarian tumor cores. A significant difference in TACC3 expression between tumor types was noted, with TACC3 being expressed less frequently in serous papillary tumors than clear cell tumors (Fisher's exact test, p = 0.0113). In contrast, TACC1 was detected in 71.4% (30 of 42) serous papillary, 60% (3 of 5) mucinous, 28.6% (2 of 7) endometroid and 54.5% (6 of 11) clear cell ovarian tumor cores. TACC1 expression was less frequent in endometroid than in serous papillary tumors (Fisher's exact test p = 0.0406). Noticeably, TACC3 compared with TACC1 staining in serous papillary tumors was significantly different (Fisher's exact test, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2). There was no significant difference between their expression in clear cell, endometroid or mucinous tumor types. However, as it is more difficult to obtain large numbers of these less common types of ovarian cancer, it should be stressed that further analysis will be required to investigate whether relationships between tumor type and grade will hold in a larger sample set.

Mutation analysis of the TACC3 gene in familial ovarian cancer

The prevalence of structural aberrations in 4p16 noted during ovarian tumorigenesis indicates that this region could contain one or more genes whose normal role is to control the growth and maintenance of the ovarian surface epithelium [3–5]. Thus, loss of one copy of 4p16 in the developing ovarian tumor may result in haploinsufficiency, or unmask a pathogenic mutation in one or more of the genes in this region. With the evidence from the expression analysis presented above, it would appear that a significant number of ovarian cancers lack TACC3 expression. As the TACC3 gene is located within 4p16 [11], we next investigated whether constitutional mutations occur within the TACC3 gene in familial ovarian cancer. Thus, mutation analysis was performed on the TACC3 coding sequence, and the corresponding intron/exon boundaries of this 16 exon gene. Specifically, we used the Transgenomics WAVE dHPLC technology as a pre-screening approach to sample constitutional DNA from ovarian cancer patients and their unaffected relatives from 76 families from the Gilda Radner Familial Ovarian Cancer Registry. These families had previously tested negative for mutations in known ovarian cancer predisposition genes, including BRCA1 and BRCA2, and thus the underlying genetic predisposition in these families is currently unknown [2].

We identified novel sequence variants in a number of the samples, but most of these were due to polymorphisms in the intronic sequence included in the amplified products. However, novel sequence substitutions were also identified in the TACC3 coding sequence (Table 2), many of which resulted in no change at the protein level. Four nucleotide substitutions, not found in the GenBANK or SNP databases, which did alter the protein sequence were identified in both normal and affected sibs and thus also categorized as novel polymorphisms. In most cases, the alterations resulted from C to T base changes in CpG dinucleotides. Intriguingly, we identified a relatively rare insertion/deletion polymorphism in two 12mer amino acid repeats encoded by exon four [11]. The identification of this polymorphism could explain the previously reported variable number of copies of a distinct 24 amino acid repeat found in mouse TACC3 cDNAs from various sources [11, 18, 21]; although in only one case was the corresponding exon (exon 4) sequenced [18].

Significantly, in two unrelated patients from different families, we identified sequence alterations that were not present in unaffected sib(s) in the respective families or unrelated samples. In one case, a heterozygous C to T mutation in exon 6 was detected in the affected sister, but not her unaffected sister or sibling (Table 2). This mutation results in the dramatic change of amino acid 514 from glycine to negatively charged glutamic acid, and was not identified in any other normal or affected individuals from the registry, so far tested. Cross-referencing this sequence to GenBANK revealed only five occurrences of this mutation in cDNAs from the Expressed Sequence Tag database, all of which were derived from tumor tissues (including brain tumors and leukemias). The underlying c.1541G>A nucleotide substitution was detected in the SNP database from a survey of 71 individuals (subdivided into three panels based upon ethnicity), with the minor A allele frequency ranging from 0.312 in the Caucasian North American panel to 0.109 in the African American panel, frequencies that are higher than our detection of this allele in the Gilda Radner registry i.e. in one affected individual in the 76 families tested. In the second family, a heterozygous constitutional mutation was detected in exon 3 that resulted in a serine-leucine change at amino acid 93 in a patient diagnosed with clear cell ovarian carcinoma. This sequence change was not identified in other individuals from the registry, or in the GenBANK and SNP databases. The mother of this patient was previously diagnosed with uterine cancer (although the exact subtype of tumor was not recorded), and was also heterozygous for the same mutation. Two sisters, who are currently disease-free, do not carry the mutation. These data suggest that TACC3 may be a new familial predisposition or modifier locus for gynecological cancer.

Discussion

TACC1 and TACC3 are expressed in the epithelial components of several tissues in the body, including the mammary gland and the ovary. Based upon inferences from current SAGE data and accumulating genomic analysis, the specific goal of this report was to determine the potential significance of these proteins in the development of ovarian cancer. This has revealed that 78.5% of ovarian tumors lack appreciable expression of TACC1 and/or TACC3. In particular, we have determined that 67.7% (44 of 65) of ovarian tumors lose expression of TACC3. Subdivision of the tumors suggested a difference in the distribution pattern of expression of the two TACC proteins, with TACC3 loss being more common in serous papillary carcinoma compared with clear cell carcinomas, while TACC1 staining was less frequent in endometroid than in serous papillary tumor cores. However, due to the relatively small numbers of tumors in each histological category, particularly the rarer endometroid and mucinous subtypes, firm conclusions about the exact distribution pattern will require analysis of a much larger sample set. Furthermore, we detected constitutional mutations in the TACC3 gene in ovarian cancer patients from the Gilda Radner Familial Ovarian Cancer registry, in the absence of mutations in known predisposition genes.

During growth and progression, tumors can undergo a substantial amount of genomic rearrangement, including translocations, deletions and amplifications. Although many of these changes are random, due to the inherent genomic instability that can occur during tumor cell division, consistent abnormalities in the same or related tumor types can suggest that one or more genes in a particular region may be involved in the pathogenesis of the disease. Several different cancers, and in particular, breast, ovarian, endometrial and cervical cancers exhibit loss of 4p16 [5, 22–27], the site of the TACC3 gene [11, 10]. Thus, if TACC3 were a significant player in the pathogenesis of cancer, we would expect that a proportion of these tumors could similarly lose expression of TACC3. Indeed, in a survey of 500 resected breast tumors, TACC3 protein was significantly reduced in approximately 50% of the tumors [28]. In contrast, Affymetrix microarray analysis has revealed that levels of TACC3 mRNA increase during the transition of breast cancer from preinvasive ductal carcinoma in situ to invasive ductal carcinoma [29], suggesting that TACC3 may impart a proliferative advantage to a subset of breast cancers. A more recent study has indicated that TACC2 and TACC3 are members of a set of 21 proteins that are strong prognostic indicators of clinical outcome in breast cancer [30]. In addition, TACC3 is located within 200 kb of a translocation breakpoint cluster region associated with multiple myeloma, which results in TACC3 upregulation. This suggests that an increase in TACC3 may contribute to the pathogenesis of this B-Cell disorder [11]. A similar dichotomy in the expression pattern of TACC1 has been observed, in that TACC1 can be upregulated or lost in cancer [28, 31, 32]. This may in part be explained by as yet unidentified tissue specific functions of these proteins or the existence of cancer-associated alternative splice products, as evidenced for TACC1 in gastric cancer [32]. However, currently there is no firm evidence for alternative splicing of TACC3 in normal or cancerous tissues.

Each human TACC gene maps to a region of the genome that is consistently associated with tumorigenesis and progression. Rearrangements of the short arm of chromosome 8 are noted in several different cancers [3, 33–35]. Typically, these rearrangements span a significant portion of 8p21-8p11, encompassing the TACC1 locus. Similarly, loss of chromosome 10, in particular the region of chromosome 10q25-26 flanked by the DNA markers D10S221 to D10S216, which encompasses the TACC2 locus, is a frequent occurrence in cancers of different origins (Reviewed in [36]). While this could suggest that the TACC genes may be mutated in a proportion of these cancers, to our knowledge, no report has directly assessed this possibility. With the prevalence of aberrations in the expression of TACC3 in the ovarian tumor arrays, we screened the coding sequence of the TACC3 gene in 76 ovarian cancer families that do not have mutations in known ovarian predisposition loci, such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 [1, 2]. This led to the identification of several new coding polymorphisms, which were found in normal and affected individuals in our test subjects. With the relatively late age of onset of ovarian cancer, it remains possible that some of the siblings that have been classified as normal may actually be asymptomatic carriers. Thus, some of these novel polymorphisms may actually represent low penetrance modifiers of ovarian cancer risk, in a similar manner to BARD1 polymorphisms that were subsequently shown to be associated with increased breast cancer risk in the general population [37–39].

In addition, we identified two germline constitutional missense mutations that were specific to the affected patient, and were not found in currently unaffected siblings or unaffected members of the Gilda Radner registry. In addition, the Ser93Leu substitution was not found in normal individuals or cDNAs from the SNP or GenBANK databases. Significantly, the mother of the patient that carried the Ser93Leu substitution was also heterozygous for the same mutation and had previously been treated for a uterine cancer of undetermined type, while two siblings without this mutation remain disease free to date. In the Gilda Radner registry, the risk for uterine cancer is approximately five fold higher than the general population, and this risk increases with the number of first degree relatives diagnosed with ovarian cancer [40]. A similar finding was observed in a separate genealogy-based study [41]. Indeed, a link between ovarian and uterine cancer may not be surprising given the common embryonic origin of the epithelium of the female reproductive tract i.e. the coelomic epithelium [42]. In an independent study, in one BRCA1 linked family, the daughter of a patient diagnosed with ovarian cancer not only had bilateral breast cancer, but also uterine leiomyomata [43, 44]. In addition, a germ line missense mutation in the BRCA1 associated protein BARD1 can give rise to independent tumors in the breast, ovary (clear cell carcinoma) and endometrium (also a clear cell carcinoma) [37]. This connection is particularly intriguing considering the recent observation that the C. elegans TAC protein interacts directly with the C. elegans homologue of BARD1 [45]. Unfortunately, we were unable to obtain additional tumor samples from our patients or material from an additional affected family member for further study. The Gly514Glu mutation, noted in the second family, is also present in five cDNAs derived from cancer cell lines or tumors in the expressed sequence tag (EST) database. Interestingly, the TACC3 sequence cloned by McKeveney et al [21] also contains the Gly514Glu substitution. Once again, this sequence was derived from a leukemia cell line, not from a normal tissue counterpart, suggesting that mutations in TACC3 may also be a feature of other hematological malignancies, in addition to the previously documented aberrant expression observed in multiple myeloma [46]. Intriguingly, two previous studies have reported an increased risk of ovarian cancer in the daughters of mothers with multiple myeloma [47, 48], raising the possibility that TACC3 is a candidate gene contributing to the familial association of these two diseases. Further, larger population studies will be required to confirm whether both these changes represent rare polymorphisms, low penetrance modifiers that contribute to ovarian cancer development and/or are direct pathological mutations.

Potential functional significance of alterations of TACC3 in the ovarian surface epithelium

The TACC genes were first identified as potential oncogenes and tumor suppressors in breast cancer [10, 36, 49]. However, it is apparent from their proposed functions in cell division, transcriptional and posttranscriptional control, that they have the potential to interact with pathways that are commonly mutated in several different forms of cancer. TACC3 has an evolutionarily conserved interaction with the microtubule associated proteins and mitotic regulators, chTOG [50], and Aurora A kinase, and can be phosphorylated by the latter (Reviewed in [51]). In addition, a genetic interaction between TACC3 and p53 has been suggested, based upon work carried out in mice [52]. Intriguingly, we have recently found that TACC3 associates with a BRCA1-containing complex (Lauffart et al unpublished), and Boulton et al [45] have shown that C. elegans TAC directly interacts with the C. elegans homologue of BARD1. These functional interactions suggest that loss of the TACC proteins may promote tumor progression by increasing aberrations in centrosomal duplication and function, or DNA damage responses [10, 53]. In addition, TACC3 has been shown to interact with nuclear localized transcription factors [18, 51, 54] and histone acetyltransferases [55]. Overexpression of TACC3 in hematopoietic cells results in aberrant localization of FOG1 [54], a regulator of the GATA transcription factors. Intriguingly, similar to TACC3, two members of this latter family, GATA 4 and GATA 6, are either lost or mislocalized in ovarian tumors [20]. Given the potential ability of TACC3 to interact with proteins known to be involved in ovarian tumorigenesis, our data therefore raise the possibility that TACC3 mutation, mislocalization or loss may serve as alternative mechanisms of functional inactivation of GATA4/6 and BRCA1 leading to the dedifferentiation and malignant development of the ovarian surface epithelium.

Conclusion

This report documents the first recorded analysis of the TACC genes during the development of ovarian cancer. We have now shown that 78.5% of ovarian tumors lack appreciable expression of TACC1 and/or TACC3 proteins, confirming the inferences made from published SAGE analysis. Together with the novel finding that constitutional mutations in the TACC3 gene may be associated with a subset of familial ovarian/gynecological malignancies, this study, therefore, suggests that the TACCs, and TACC3 in particular, are intimately involved in the mechanisms leading to the development of ovarian cancer.

References

Gayther SA, Russell P, Harrington P, Antoniou AC, Easton DF, Ponder BA: The contribution of germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations to familial ovarian cancer: no evidence for other ovarian cancer-susceptibility genes. Am J Hum Genet. 1999, 65: 1021-1029. 10.1086/302583.

Werness BA, Ramus SJ, Dicioccio RA, Whittemore AS, Garlinghouse-Jones K, Oakley-Girvan I, Tsukada Y, Harrington P, Gayther SA, Ponder BA, Piver MS: Histopathology, FIGO stage, and BRCA mutation status of ovarian cancers from the Gilda Radner Familial Ovarian Cancer Registry. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2004, 23: 29-34. 10.1097/01.pgp.0000101083.35393.cd.

Rao PH, Harris CP, Yan LX, Li XN, Mok SC, Lau CC: Multicolor spectral karyotyping of serous ovarian adenocarcinoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2002, 33: 123-132. 10.1002/gcc.1221.

Suzuki S, Moore DH, Ginzinger DG, Godfrey TE, Barclay J, Powell B, Pinkel D, Zaloudek C, Lu K, Mills G, Berchuck A, Gray JW: An approach to analysis of large-scale correlations between genome changes and clinical endpoints in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2000, 60: 5382-5385.

Ramus SJ, Pharoah PD, Harrington P, Pye C, Werness B, Bobrow L, Ayhan A, Wells D, Fishman A, Gore M, Dicioccio RA, Piver MS, Whittemore AS, Ponder BA, Gayther SA: BRCA1/2 Mutation Status Influences Somatic Genetic Progression in Inherited and Sporadic Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Cases. Cancer Res. 2003, 63: 417-423.

Gene Expression Omnibus repository. http://www ncbi nlm nih gov/SAGE/. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SAGE/]

Velculescu VE, Zhang L, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW: Serial analysis of gene expression. Science. 1995, 270: 484-487.

SAGE Tag to Gene Mapping Retrieve by SAGE tag: ACTCAATAAA. http://www ncbi nlm nih gov/SAGE/index cgi?cmd=tagsearch&org=Hs&tag=ACTCAATAAA&anchor=NLAIII. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SAGE/index.cgi?cmd=tagsearch&org=Hs&tag=ACTCAATAAA&anchor=NLAIII]

SAGE Tag to Gene Mapping Retrieve by SAGE tag: TTTCATTGCC. http://www ncbi nlm nih gov/sage/index cgi?&anchor=NLAIII&cmd=tagsearch&tag=TTTCATTGCC&org=Hs. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sage/index.cgi?&anchor=NLAIII&cmd=tagsearch&tag=TTTCATTGCC&org=Hs]

Still IH, Hamilton M, Vince P, Wolfman A, Cowell JK: Cloning of TACC1, an embryonically expressed, potentially transforming coiled coil containing gene, from the 8p11 breast cancer amplicon. Oncogene. 1999, 18: 4032-4038. 10.1038/sj.onc.1202801.

Still IH, Vince P, Cowell JK: The third member of the transforming acidic coiled coil-containing gene family, TACC3, maps in 4p16, close to translocation breakpoints in multiple myeloma, and is upregulated in various cancer cell lines. Genomics. 1999, 58: 165-170. 10.1006/geno.1999.5829.

National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer ResearchTechnology Initiatives, Tissue Array Research Program (TARP). http://ccr cancer gov/tech_initiatives/tarp/default asp. [http://ccr.cancer.gov/tech_initiatives/tarp/default.asp]

Shimizu Y, Kamoi S, Amada S, Akiyama F, Silverberg SG: Toward the development of a universal grading system for ovarian epithelial carcinoma: testing of a proposed system in a series of 461 patients with uniform treatment and follow-up. Cancer. 1998, 82: 893-901. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19980301)82:5<893::AID-CNCR14>3.0.CO;2-W.

Morgan RJ, Alvares RR, Armstrong DK, Copeland L, Fiorica J, Fishman DD, Fowler J, Gershenson D, Greer BE, Johnston C, Kessinger A, Lele S, Locker GY, Matulonis V, Ozols RF, Sabbatini P, Teng N: NCCN Practice guidelines for ovarian cancer. National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Complete library of NCCN Oncology Practice Guidelines. 2000

Kuklin A, Munson K, Gjerde D, Haefele R, Taylor P: Detection of single-nucleotide polymorphisms with the WAVE DNA fragment analysis system. Genet Test. 1997, 1: 201-206.

dbSNP Homepage. http://www ncbi nlm nih gov/SNP/index html. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/index.html]

Aitola M, Sadek CM, Gustafsson JA, Pelto-Huikko M: Aint/Tacc3 is highly expressed in proliferating mouse tissues during development, spermatogenesis, and oogenesis. J Histochem Cytochem. 2003, 51: 455-469.

Sadek CM, Jalaguier S, Feeney EP, Aitola M, Damdimopoulos AE, Pelto-Huikko M, Gustafsson J: Isolation and characterization of AINT: a novel ARNT interacting protein expressed during murine embryonic development. Mech Dev. 2000, 97: 13-26. 10.1016/S0925-4773(00)00415-9. http://PM:0011025203

Sadek CM, Pelto-Huikko M, Tujague M, Steffensen KR, Wennerholm M, Gustafsson JA: TACC3 expression is tightly regulated during early differentiation. Gene Expr Patterns. 2003, 3: 203-211. 10.1016/S1567-133X(02)00066-2.

Capo-chichi CD, Roland IH, Vanderveer L, Bao R, Yamagata T, Hirai H, Cohen C, Hamilton TC, Godwin AK, Xu XX: Anomalous expression of epithelial differentiation-determining GATA factors in ovarian tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2003, 63: 4967-4977.

McKeveney PJ, Hodges VM, Mullan RN, Maxwell P, Simpson D, Thompson A, Winter PC, Lappin TR, Maxwell AP: Characterization and localization of expression of an erythropoietin- induced gene, ERIC-1/TACC3, identified in erythroid precursor cells. Br J Haematol. 2001, 112: 1016-1024. 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02644.x.

Climent J, Martinez-Climent JA, Blesa D, Garcia-Barchino MJ, Saez R, Sanchez-Izquierdo D, Azagra P, Lluch A, Garcia-Conde J: Genomic loss of 18p predicts an adverse clinical outcome in patients with high-risk breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2002, 8: 3863-3869.

Forozan F, Mahlamaki EH, Monni O, Chen Y, Veldman R, Jiang Y, Gooden GC, Ethier SP, Kallioniemi A, Kallioniemi OP: Comparative genomic hybridization analysis of 38 breast cancer cell lines: a basis for interpreting complementary DNA microarray data. Cancer Res. 2000, 60: 4519-4525.

Wang ZC, Lin M, Wei LJ, Li C, Miron A, Lodeiro G, Harris L, Ramaswamy S, Tanenbaum DM, Meyerson M, Iglehart JD, Richardson A: Loss of Heterozygosity and Its Correlation with Expression Profiles in Subclasses of Invasive Breast Cancers. Cancer Res. 2004, 64: 64-71.

Sherwood JB, Shivapurkar N, Lin WM, Ashfaq R, Miller DS, Gazdar AF, Muller CY: Chromosome 4 deletions are frequent in invasive cervical cancer and differ between histologic variants. Gynecol Oncol. 2000, 79: 90-96. 10.1006/gyno.2000.5922.

Nagase S, Sato S, Tezuka F, Wada Y, Yajima A, Horii A: Deletion mapping on chromosome 10q25-q26 in human endometrial cancer. Br J Cancer. 1996, 74: 1979-1983.

Sato T, Saito H, Morita R, Koi S, Lee JH, Nakamura Y: Allelotype of human ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 1991, 51: 5118-5122.

Conte N, Charafe-Jauffret E, Delaval B, Adelaide J, Ginestier C, Geneix J, Isnardon D, Jacquemier J, Birnbaum D: Carcinogenesis and translational controls: TACC1 is down-regulated in human cancers and associates with mRNA regulators. Oncogene. 2002, 21: 5619-5630. 10.1038/sj.onc.1205658.

Ma XJ, Salunga R, Tuggle JT, Gaudet J, Enright E, McQuary P, Payette T, Pistone M, Stecker K, Zhang BM, Zhou YX, Varnholt H, Smith B, Gadd M, Chatfield E, Kessler J, Baer TM, Erlander MG, Sgroi DC: Gene expression profiles of human breast cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003, 100: 5974-5979. 10.1073/pnas.0931261100.

Jacquemier J, Ginestier C, Rougemont J, Bardou VJ, Charafe-Jauffret E, Geneix J, Adelaide J, Koki A, Houvenaeghel G, Hassoun J, Maraninchi D, Viens P, Birnbaum D, Bertucci F: Protein expression profiling identifies subclasses of breast cancer and predicts prognosis. Cancer Res. 2005, 65: 767-779.

Rhodes DR, Barrette TR, Rubin MA, Ghosh D, Chinnaiyan AM: Meta-analysis of microarrays: interstudy validation of gene expression profiles reveals pathway dysregulation in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2002, 62: 4427-4433.

Line A, Slucka Z, Stengrevics A, Li G, Rees RC: Altered splicing pattern of TACC1 mRNA in gastric cancer. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2002, 139: 78-83. 10.1016/S0165-4608(02)00607-6.

Adelaide J, Chaffanet M, Imbert A, Allione F, Geneix J, Popovici C, van Alewijk D, Trapman J, Zeillinger R, Borresen-Dale AL, Lidereau R, Birnbaum D, Pebusque MJ: Chromosome region 8p11-p21: refined mapping and molecular alterations in breast cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1998, 22: 186-199. 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2264(199807)22:3<186::AID-GCC4>3.0.CO;2-S.

Pan Y, Lui WO, Nupponen N, Larsson C, Isola J, Visakorpi T, Bergerheim US, Kytola S: 5q11, 8p11, and 10q22 are recurrent chromosomal breakpoints in prostate cancer cell lines. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2001, 30: 187-195. 10.1002/1098-2264(2000)9999:9999<::AID-GCC1075>3.3.CO;2-8.

Theillet C, Adelaide J, Louason G, Bonnet-Dorion F, Jacquemier J, Adnane J, Longy M, Katsaros D, Sismondi P, Gaudray P: FGFRI and PLAT genes and DNA amplification at 8p12 in breast and ovarian cancers. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1993, 7: 219-226.

Lauffart B, Gangisetty O, Still IH: Molecular cloning, genomic structure and interactions of the putative breast tumor suppressor TACC2. Genomics. 2003, 81: 192-201. 10.1016/S0888-7543(02)00039-3.

Thai TH, Du F, Tsan JT, Jin Y, Phung A, Spillman MA, Massa HF, Muller CY, Ashfaq R, Mathis JM, Miller DS, Trask BJ, Baer R, Bowcock AM: Mutations in the BRCA1-associated RING domain (BARD1) gene in primary breast, ovarian and uterine cancers. Hum Mol Genet. 1998, 7: 195-202. 10.1093/hmg/7.2.195.

Karppinen SM, Heikkinen K, Rapakko K, Winqvist R: Mutation screening of the BARD1 gene: evidence for involvement of the Cys557Ser allele in hereditary susceptibility to breast cancer. J Med Genet. 2004, 41: e114-10.1136/jmg.2004.020669.

Ishitobi M, Miyoshi Y, Hasegawa S, Egawa C, Tamaki Y, Monden M, Noguchi S: Mutational analysis of BARD1 in familial breast cancer patients in Japan. Cancer Lett. 2003, 200: 1-7. 10.1016/S0304-3835(03)00387-2.

Jishi MF, Itnyre JH, Oakley-Girvan IA, Piver MS, Whittemore AS: Risks of cancer among members of families in the Gilda Radner Familial Ovarian Cancer Registry. Cancer. 1995, 76: 1416-1421.

Kerber RA, Slattery ML: The impact of family history on ovarian cancer risk. The Utah Population Database. Arch Intern Med. 1995, 155: 905-912. 10.1001/archinte.155.9.905.

Auersperg N, Wong AS, Choi KC, Kang SK, Leung PC: Ovarian surface epithelium: biology, endocrinology, and pathology. Endocr Rev. 2001, 22: 255-288. 10.1210/er.22.2.255.

Paley PJ, Swisher EM, Garcia RL, Agoff SN, Greer BE, Peters KL, Goff BA: Occult cancer of the fallopian tube in BRCA-1 germline mutation carriers at prophylactic oophorectomy: a case for recommending hysterectomy at surgical prophylaxis. Gynecol Oncol. 2001, 80: 176-180. 10.1006/gyno.2000.6071.

Agoff SN, Mendelin JE, Grieco VS, Garcia RL: Unexpected gynecologic neoplasms in patients with proven or suspected BRCA-1 or -2 mutations: implications for gross examination, cytology, and clinical follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002, 26: 171-178. 10.1097/00000478-200202000-00003.

Boulton SJ, Martin JS, Polanowska J, Hill DE, Gartner A, Vidal M: BRCA1/BARD1 Orthologs Required for DNA Repair in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Biol. 2004, 14: 33-39. 10.1016/j.cub.2003.11.029.

Stewart JP, Thompson A, Santra M, Barlogie B, Lappin TR, Shaughnessy JJ: Correlation of TACC3, FGFR3, MMSET and p21 expression with the t(4;14)(p16.3;q32) in multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2004, 126: 72-76. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.04996.x.

Hemminki K, Granstrom C: Familial clustering of ovarian and endometrial cancers. Eur J Cancer. 2004, 40: 90-95. 10.1016/S0959-8049(03)00627-0.

Stratton JF, Thompson D, Bobrow L, Dalal N, Gore M, Bishop DT, Scott I, Evans G, Daly P, Easton DF, Ponder BA: The genetic epidemiology of early-onset epithelial ovarian cancer: a population-based study. Am J Hum Genet. 1999, 65: 1725-1732. 10.1086/302671.

Chen HM, Schmeichel KL, Mian IS, Lelievre S, Petersen OW, Bissell MJ: AZU-1: A Candidate Breast Tumor Suppressor and Biomarker for Tumor Progression. Mol Biol Cell. 2000, 11: 1357-1367.

Gard DL, Becker BE, Josh RS: MAPping the eukaryotic tree of life: structure, function, and evolution of the MAP215/Dis1 family of microtubule-associated proteins. Int Rev Cytol. 2004, 239: 179-272.

Still IH, Vettaikkorumakankauv AK, DiMatteo A, Liang P: Structure-function evolution of the transforming acidic coiled coil genes revealed by analysis of phylogenetically diverse organisms. BMC Evol Biol. 2004, 4: 16-10.1186/1471-2148-4-16.

Piekorz RP, Hoffmeyer A, Duntsch CD, McKay C, Nakajima H, Sexl V, Snyder L, Rehg J, Ihle JN: The centrosomal protein TACC3 is essential for hematopoietic stem cell function and genetically interfaces with p53-regulated apoptosis. EMBO J. 2002, 21: 653-664. 10.1093/emboj/21.4.653.

Gergely F, Karlsson C, Still I, Cowell J, Kilmartin J, Raff JW: The TACC domain identifies a family of centrosomal proteins that can interact with microtubules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000, 97: 14352-14357. 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14352.

Garriga-Canut M, Orkin SH: Transforming acidic coiled-coil protein 3 (TACC3) controls friend of GATA-1 (FOG-1) subcellular localization and regulates the association between GATA-1 and FOG-1 during hematopoiesis. J Biol Chem. 2004, 279: 23597-23605. 10.1074/jbc.M313987200.

Gangisetty O, Lauffart B, Sondarva GV, Chelsea DM, Still IH: The transforming acidic coiled coil proteins interact with nuclear histone acetyltransferases. Oncogene. 2004, 23: 2559-2563. 10.1038/sj.onc.1207424.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6874/5/8/prepub

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the Elsa U. Pardee Foundation, developmental funds support from the Roswell Park Cancer Institute, and Core grant P30-CA16056-27 from the National Cancer Institute. We thank Dr James L. Kepner (Department of Biostatistics) for his helpful advice.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

BL analyzed the tumor microarrays, and performed all statistical analysis and data presentation. MMV and JDB performed the immunohistochemical procedures. WAVE dHPLC and mutation analysis of families from the Gilda Radner Familial Ovarian Registry was carried out by RE, DC, and RAD. IHS conceived and designed the project, analyzed tumor microarray data and drafted the complete manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Lauffart, B., Vaughan, M.M., Eddy, R. et al. Aberrations of TACC1 and TACC3 are associated with ovarian cancer. BMC Women's Health 5, 8 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-5-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-5-8