Abstract

Background

Genetic variants of proteins involved in lipid metabolism may play an important role in determining the susceptibility for complications associated with type II diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Goal of the present study was to determine the association of cholesteryl ester transfer protein Taq I B, D442G, and APOE Hha I polymorphisms with T2DM and its complications.

Methods

Study subjects were 136 patients and 264 healthy controls. All polymorphisms were detected using PCR-RFLP and statistical analysis done with χ2 test and ANOVA.

Results

Although CETP Taq I B polymorphism was not associated with the T2DM, yet B1B2 genotype was significantly (p = 0.028) associated with high risk of hypertension in diabetic patients (OR = 3.068, 95% CI 1.183–7.958). In North Indians D442G variation in CETP gene was found to be absent. Frequency of APOE HhaI polymorphism was also not different between patients and controls. In diabetic patients having neuropathy and retinopathy significantly different levels of total-cholesterol [(p = 0.001) and (p = 0.029) respectively] and LDL-cholesterol [(p = 0.001) and (p = 0.001) respectively] were observed when compared to patients with T2DM only. However, lipid levels did not show any correlation with the CETP Taq I B and APOE Hha I genetic polymorphisms.

Conclusion

CETP Taq I B and APOE Hha I polymorphism may not be associated with type II diabetes mellitus in North Indian population, however CETP Taq I B polymorphism may be associated with hypertension along with T2DM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Dyslipidemia is a major cardiovascular risk factor in type II diabetes mellitus (T2DM) with coronary heart disease being the most common cause of death. Risk relates to raised triglycerides (TG) and decreased high density lipoproteins (HDL) as well as raised low density lipoproteins (LDL). In diabetes, lipid risk thresholds are lower and interactions with other cardiovascular risk factors are more powerful, compared with general population. Hypertension is upto twice as common in diabetic patients as in general population [1]. Studies have shown that lipid abnormalities might contribute to the development and progression of diabetic nephropathy [2]. Hypercholesterolemia is a major determinant of decline of renal function in patients with diabetes [3].

Genetic polymorphisms of the enzymes and proteins involved in lipid metabolism like cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) and apolipoprotein E have been shown to affect plasma lipid concentrations [4]. CETP modifies HDL, LDL and very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) levels. It transfers cholesterol esters (CE) from CE rich particles (HDL and LDL) to triglyceride rich particles (VLDL) in exchange of triglyceride from the latter [5]. There has been an ongoing debate as to whether CETP is pro- or anti-atherogenic as it provides a mechanism for the transfer of cholesterol from the cardioprotective HDL subfraction to the potentially atherogenic LDL subfraction [6]. CETP gene encompasses 16 exons and it has been localized on chromosome 16q21. Several genetic polymorphisms have been reported which may be associated with alteration in CETP activity. Taq I B polymorphism has been most widely studied, which results from a silent mutation in nucleotide 277, in intron 1 of the gene. The polymorphism has been associated with decreased CETP mass and an increase in HDL-cholesterol [7–9]. The Taq I polymorphism B1 allele of CETP has been shown to be an independent risk factor for development of cerebral vascular disease, in patients with T2DM [10]. The locus has also been reported to modulate the risk for diabetic complications in patients with T2DM and effect seems to be different between men and women [11]. Another polymorphism D442G (Asp442-->Gly) in exon 15 of CETP is located close to the active site of the enzyme and leads to reduced plasma CETP mass and specific activity [12]. The mutation is more prevalent in Japanese subjects with high HDL-levels (>100 mg/dL) [12–14].

Apolipoprotein E (Apo E) plays a central role in clearance of lipoprotein remnants by serving as a ligand for LDL and apo E receptors. The gene for apo E is approximately 3.7 kb in length and contains 4 exons. It has been mapped to chromosome 19q13 in humans. Three different APOE alleles (ε2, ε3, and ε4) give six phenotypes. The protein isoforms result from interchanges of cysteine and arginine at the residue 112 and 158. In apo E2, cysteine occurs at both positions; in apo E4 arginine is located at both positions; and in apo E3 cysteine occupies position 112 and arginine, position 158. Based on homozygosity or heterozygosity of these apo E isoproteins, a total of six phenotypes (E2/2, E3/3, E4/4, E4/2, E4/3, and E3/2) are present in the population [15]. APOE gene polymorphism has been shown to be associated with the development of diabetic nephropathy in T2DM patients in Taiwan [2]. Apo ε4 allele may speed up the rate of decline of glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in patients with progressive diabetic renal disease [16]. Studies have shown ε2 as positive and ε4 as negative factor for the progression of diabetic nephropathy [17, 18].

Genetic epidemiologic studies, familial aggregation, familial transmission pattern, and twin concordance rates suggest the importance of genetic susceptibility underlying the development of T2DM. High incidence of disease in North Indian population and lack of study exploring the genetic basis of diabetes made us to study the association of CETP Taq I B and D442G; and APOE Hha I polymorphisms with T2DM.

Methods

Subjects

The study comprised of 136 T2DM patients (mean age 46.96 ± 9.38 yr.) and 264 healthy individuals (mean age 47.39 ± 16.64 yr.). Patients were enrolled from the outpatients attending the clinics of Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Institute of Medical Sciences from November 2003 to April 2004. Most patients belonged to State of Uttar Pradesh in North India. Subjects were classified as diabetic if they had fasting glucose concentrations ≥126 mg/dL or 2-hour glucose concentrations ≥200 mg/dL after a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test [19, 20]. These patients were further classified according to their complication into groups – neuropathy, nephropathy, retinopathy, hypertension, and T2DM without complication, after reviewing their medical chart. Neuropathy was defined as presence of distal sensory loss in feet. Nephropathy was defined as presence of gross albumin in urine >300 mg/d in 24 hr collection of urine sample. Retinopathy was defined as presence of retinal vascular microaneurysm, blot hemorrhages, or cotton wool spots. Hypertension was defined as presence of blood pressure of ≥140/90 mm Hg at three different readings on different days. None of the patients were on lipid lowering therapy at the time of drawing their sample. All the patients were on oral hypoglycemic agent Glimepride or Metformin or both.

The controls were the healthy staff members of institute with negative oral glucose tolerance test. Only those patients and controls were included who did not have the history of coronary artery disease, neoplasia, or other metabolic disorder.

Study was approved from the ethical committee of the institute. After an informed consent an overnight fasting blood sample was taken in EDTA for analysis of lipids and DNA. The plasma was separated by centrifugation at 3000 rpm within 10 minutes of blood collection for the lipid analysis. The genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leucocytes pellet using the standard salting out method [21].

Lipids levels

In plasma, total cholesterol, triglyceride, and HDL-cholesterol were analyzed using commercially available kits (Accurex Biomedical Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India). For HDL-cholesterol estimation, selective precipitation of other lipoproteins was done using sodium tungstate and magnesium chloride. LDL-cholesterol was calculated according to previously described method [22].

Genotyping

CETP Taq I B and D442G polymorphisms

A fragment of 535 bp in intron 1 of the CETP gene was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in a DNA thermal cycler (DNA Engine PTC-100, MJ Research, Inc) using primers forward 5'-CACTAGCCCAGAGAGA-GGAGTGCC-3' and, reverse 5'-CTGAGCCCAGCCGCACACTAAC-3' [23]. For D442G polymorphism analysis primers used to amplify exon 15 and flanking sequences were as follows: forward 5'-GTGTTTACAGCCCTCATGAAC-3' and reverse 5'-AAGCCAAAGTCCATCTCTGCAG-3' [24]. Each amplification was performed using 200 ng of genomic DNA in a volume of 25 μl using 12.5 pmol of each primer, 200 μM each dNTPs, 15 mM MgCl2, 100 mM Tris and two units of Taq polymerase (Bangalore Genei, Bangalore). DNA templates were initially denatured at 95°C for three minutes, followed by 30 cycles with denaturation at 95°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 60°C for 30 seconds and, extension at 72°C for 45 seconds and finally, an extension at 72°C for five minutes. The PCR products were subjected to restriction digestion with 4 U of the restriction endonuclease Ta qI for 15 μl of PCR sample at 65°C for three hours in the buffer recommended by the manufacturer (MBI Fermentas, USA).

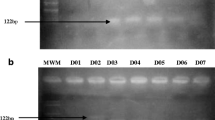

Taq I B genotype was determined by electrophoresis of restricted PCR product on 2% agarose gel followed by ethidium bromide staining. Presence of Taq I site (B1 allele) gave two bands of 174 bp and 361 bp and absence (B2 allele) showed one band of 535 bp.

For genotyping of D442G polymorphism, Taq I digested PCR products were run on 20% polyacrylamide gel. This product has two sites for Taq I. Homozygous subjects with DD give two bands (218 bp and 69 bp) and heterozygous show four bands (218 bp, 69 bp, 41 bp and 28 bp) and homozygous for G allele show three bands (218 bp, 41 bp, and 28 bp).

APOE polymorphism

The primers used to analyze the APOE were as follows: Forward 5'-ACAGAATTCGCCCCGGCCTGGTACAC-3' and Reverse 5' TAAGCTTGGCACGGCTGTCCAAGG A-3' [25]. The PCR products were initially denatured at 95°C for five minute, cycling conditions were 95°C for one minute, 58°C for one minute, 70°C for one minute (30 cycles) followed by final extension at 72°C for 10 minutes. After PCR amplification, 10 units of Hha I were added for digestion (>3 h at 37°C). The digested product was run on 20% polyacrylamide gel at 300 V, stained with ethidium bromide and visualized under ultraviolet light.

Statistical evaluation

Data was analyzed using the statistical software (SPSS vs.11.5). Direct gene counting method was used to determine the frequency of genotypes and alleles. The chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was used to determine differences in frequencies. P-value < 0.05 was considered as significant. All continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD. The normality in the distribution of total-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, triglyceride and LDL-cholesterol was confirmed by using normal probability plots. Since total-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, triglyceride and LDL-cholesterol were not distributed normally they were naturally log transformed. Significant covariates for each dependent trait were identified using Pearson's correlation with 5% level of significance. Sex and BMI were found to be significant covariates for total cholesterol, sex for triglyceride and HDL-cholesterol, and BMI for LDL-cholesterol. Total cholesterol, triglyceride, HDL-cholesterol, and LDL-cholesterol values were subjected to a linear regression procedure to obtain adjusted values for significant covariates. ANOVA was performed to determine genetic source of variation for biochemical traits in control population separately. Lipid variables were taken as dependent variable and the genetic marker as independent. If this test was significant, Tukey posthoc test was performed to find out which genotype/allele differed significantly from others. All calculations were done in total samples as well as in males and females separately

Results

Table 1 and table 2 show the demographic and lipid profile of study population respectively. Plasma concentrations of total-cholesterol (p = 0.001) and LDL-cholesterol (p = 0.00008) levels were significantly higher in T2DM patients than in controls but HDL-cholesterol and triglyceride levels were not significantly different (Table 2 – unadjusted values). After stratification of population on the basis of gender same pattern of lipid profile was found. Overall, males had lower circulating levels than females in patients as well as in controls.

CETP Taq I B polymorphism

In controls the frequency of B1 and B2 alleles of CETP Taq I B gene was 52.65% and 47.35% respectively, which is similar to most of Caucasian populations. The observed genotypes B1B1, B1B2, and B2B2 were in Hardy Weinberg equilibrium. Analysis of the polymorphism showed that the frequency of B2 allele and B2B2 genotype was not significantly different in patients and controls (43.75% vs 47.35% and 16.91% vs 21.97%, Table 3). Further stratification of data according to gender (Table 4) did not show any association with the disease. After subdividing study population into different age groups no significant association was found but B1B2 genotype showed weak association and risk (p = 0.054; OR 3.826, 95% CI 0.916–15.98) for disease in 61–75 age group (Table 5).

When patient population was sub-divided according to the associated complications viz., neuropathy, nephropathy, retinopathy, hypertension, and no complication, B1B2 genotype was significantly (p = 0.018) associated with high risk of hypertension in diabetic patients (OR = 3.068, 95% CI 1.183–7.958), and B1B1 was found to be significantly protective (p = 0.038, OR = 0.139, 95% CI 0.018–1.093) for hypertension (Table 6).

CETP D442G polymorphism

For D442G no polymorphism was found in patient or control population, only D allele was present (Table 3).

APOE Hha I polymorphism

Frequencies of all APOE genotypes were not significantly different between the diabetic and control group in total or after stratifying according to gender or age (Table 7).

Genetic polymorphisms and lipid profile

In diabetic patients having neuropathy significantly different levels of total cholesterol (p = 0.001) and LDL-cholesterol (p = 0.001) were found than in T2DM only patients. Unadjusted values were higher in T2DM patients with neuropathy than in patients with T2DM only (total-cholesterol, 225.89 ± 45.18 mg/dL vs. 186.45 ± 51.56 mg/dL and LDL-cholesterol, 152.33 ± 41.07 mg/dL vs. 105.72 ± 44.09 mg/dL respectively) but adjusted values were higher in patients with T2DM only than in patients with T2DM and neuropathy (total-cholesterol, 5.09 ± 0.07 vs. 5.00 ± 0.06 mg/dL and LDL-cholesterol, 4.45 ± 0.09 vs. 4.32 ± 0.11 mg/dL respectively). In T2DM patients with retinopathy adjusted total-cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol levels were significantly (p = 0.029 and p = 0.001 respectively) lower (5.00 ± 0.10 vs. 5.09 ± 0.07 mg/dL and 4.29 ± 0.11 vs. 4.45 ± 0.09 mg/dL respectively) than patients with T2DM only.

Lipid profile analysis did not show any significant difference in distribution among genotypes of CETP Taq I B polymorphism or APOE Hha I polymorphism. In T2DM patients though the levels of total-cholesterol and triglyceride were higher in ε4 allele carriers than in ε2 or ε3 allele carriers, but the difference was not statistically significant (Table 8).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study of its kind in North Indian population. We studied association of CETP Taq I B, CETP D442G, and APO E Hha I polymorphisms with T2DM and with complications associated with the disease. In the present study, no association of CETP Taq I B polymorphism with the disease was found but B1B2 genotype was risk factor for hypertension along with diabetes (P = 0.028). However, B1B1 was found to be protective (P = 0.038).

CETP is a key regulator of lipid metabolism and polymorphism of the gene may be associated with complications of diabetes mellitus. B1B1 carriers have been reported to show lowest and B2B2 carriers highest HDL-cholesterol concentration [26–31]. but no association of Taq I B polymorphism was found in several other studies [32–34] A recent study in Singapore population comprising Chinese, Malays, and Asian Indians also showed that B2 allele was associated with high HDL-cholesterol concentration. Inspite of highest frequency of B2 allele, the HDL-cholesterol levels were lower in Asian Indians than in Chinese and Malays [35].

We found that B1B1 is protective for diabetes associated hypertension which seems contradictory to reports relating B1B1 with low HDL-cholesterol and B2B2 with high HDL-cholesterol. Relvas et al. [36] also found a higher prevalence of the B2B2 genotype of the CETP gene among diabetics than that observed in non-diabetics. These contradictory results indicate towards two possibilities. Firstly, Taq I B polymorphism is not the only determinant of HDL-cholesterol level, other polymorphisms or mutation in the CETP are more potent determinant. Various mutations/polymorphisms resulting in amino acid substitutions, namely A373P, I405V and R451Q, have been found to be independent variations from the Taq I B polymorphism effecting HDL-cholesterol and CETP activity [27, 33, 37–39]. Secondly, actual gene responsible/protective for hypertension may be different which is in linkage disequilibrium with CETP Taq I B polymorphism. Klerkx et al. [5] also showed that the Taq I B polymorphism is not instrumental in determining CETP or HDL-C levels, but is a marker for the -629 promoter variant.

D442G polymorphism has been implicated in alteration of CETP activity. The D442G acts in dominant negative manner with severe effect in heterozygous state [14]. A high prevalence of two different CETP gene mutations (D442G, 5.1%; intron 14G:A, 0.5%), was found in men of Japanese ancestry in the Honolulu Heart Program and mutations were associated with decreased CETP (-35%) and increased HDL-cholesterol levels (+10% for D442G) [40]. In our population exonic mutation D442G of CETP gene was not observed. In other populations of the world frequency of D442G varies greatly [41, 42], in some it is not even polymorphic [43] (Table 9). In Japan, D442G mutation in CETP gene is around 7% in random male samples [44]. Frequency of the D442G substitution in Chinese showed enormous variations (0.2%–5%) [45–48] which may be due to ethnic differences in the studied populations. Absence of D442G polymorphism shows similarity of our population with Caucasians.

Earlier studies in T2DM patients have shown that ε2 and ε4 alleles of APOE are associated with high risk for dyslipidemia, nephropathy, retinopathy, and coronary artery disease [18, 49–51] but other studies have shown contradictory results. Powell et al. [52] showed that APOE gene polymorphism is not linked to amyloid formation or progression of islet dysfunction in T2DM. No significant difference was found in APOE genotype frequencies between hypertriglyceridemic and normotriglyceridemic among T2DM patients [53]. Study in San Luis Valley, Colorado also showed, no significant effect of the APOE polymorphism on cholesterol levels among diabetics [54]. Another study in individuals with family history of diabetes showed that APOE polymorphism is not associated with lipids in men or women [55]. A previous study from Mumbai, India showed that APOE phenotype frequencies were not different between diabetic patients and healthy controls [56]. Our study also supports no association of APOE Hha I polymorphism with either T2DM or lipid variation. However molecular mechanism leading to lipid variation is not fully clear and various gene-gene and gene-environment interactions have also been observed, suggesting complex mechanisms leading to complications in T2DM patients.

Although our study found abnormal lipid profile in diabetes patients and its association with complications like diabetic neuropathy and retinopathy, yet these lipid profile abnormalities did not correlate with CETP Taq I B or APOE Hha I polymorphisms. In T2DM patients with neuropathy, unadjusted values of total-cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol were higher than, patients with T2DM only. After adjusting for covariates, results were opposite which shows the effect of covariates on lipid variation. The absence of any association of lipid profile with genetic subgroups suggest involvement of other environmental and genetic factors in the regulation of circulating lipid levels as well as the complex mechanism of T2DM.

Conclusion

CETP Taq I B and APOE Hha I polymorphism may not be associated with type II diabetes mellitus in north Indian population, however CETP Taq I B polymorphism may be associated with certain complications along with T2DM.

References

Poirier Paul, Després Jean-Pierre: Lipid Disorders in Diabetes. Textbook of diabetes 2. Edited by: Pickup JC, Williams G. 2003, Massachusetts: Bleckwell Science, 54.1-54.21.

Hsieh MC, Lin SR, Yang YC, Chen HC, Lin JN, Shin SJ: Higher frequency of apolipoprotein E2 allele in type 2 diabetic patients with nephropathy in Taiwan. J Nephrol. 2002, 15: 368-73.

Kimura H, Suzuki Y, Gejyo F, Karasawa R, Miyazaki R, Suzuki S, Arakawa M: Apolipoprotein E4 reduces risk of diabetic nephropathy in patients with NIDDM. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998, 31: 666-73.

Hadjadj S, Gallois Y, Simard G, Bouhanick B, Passa P, Grimaldi A, Drouin P, Tichet J, Marre M: Lack of relationship in long-term type 1 diabetic patients between diabetic nephropathy and polymorphisms in apolipoprotein epsilon, lipoprotein lipase and cholesteryl ester transfer protein. Genetique de la Nephropathie Diabetique Study Group. Donnees Epidemiologiques sur le Syndrome d'Insulino-Resistance Study Group. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000, 15: 1971-1976. 10.1093/ndt/15.12.1971.

Klerkx AH, Tanck MW, Kastelein JJ, Molhuizen HO, Jukema JW, Zwinderman AH, Kuivenhoven JA: Haplotype analysis of the CETP gene: not TaqIB, but the closely linked -629CA polymorphism and a novel promoter variant are independently associated with CETP concentration. Hum Mol Genet. 2003, 12: 111-123. 10.1093/hmg/ddg013.

Noone E, Roche HM, Black I, Tully AM, Gibney MJ: Effect of postprandial lipaemia and Taq 1B polymorphism of the cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) gene on CETP mass, activity, associated lipoproteins and plasma lipids. Br J Nutr. 2000, 84: 203-9.

Agellon LB, Quinet EM, Gillette TG, Drayna DT, Brown ML, Tall AR: Organization of the human cholesterylester transfer protein gene. Biochemistry. 1990, 29: 1372-1376. 10.1021/bi00458a004.

Zuliani G, Hobbs HH: EcoNI polymorphism in the human cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990, 18: 2834-

Freeman DJ, Griffin BA, Holmes AP, Lindsay GM, Gaffney D, Packard CJ, Shepherd J: Regulation of plasma HDL cholesterol and subfraction distribution by genetic and environmental factors. Associations between the TaqI B RFLP in the CETP gene and smoking and obesity. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994, 14: 336-344.

Fidani L, Goulas A, Crook R, Petersen RC, Tangalos E, Kotsis A, Hardy J: An association study of the cholesteryl ester transfer protein TaqI B polymorphism with late onset Alzheimer's disease. Neuroscience Letters. 2004, 357: 152-154. 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.11.071.

Bernard S, Moulin P, Lagrost L, Picard S, Elchebly M, Ponsin G, Chapuis F, Berthezene F: Association between plasma HDL-cholesterol concentration and Taq1B CETP genepolymorphism in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Lipid Res. 1998, 39: 59-65.

Takahashi K, Jiang XC, Sakai N, Yamashita S, Hirano K, Bujo H, Yamazaki H, Kusunoki J, Miura T, Kussie P, Matsuzawa Y, Saito Y, Tall A: A missense mutation in the cholesteryl ester transfer protein gene with possible dominant effects on plasma high density lipoproteins. J Clin Invest. 1993, 92: 2060-2064.

Brown ML, Inazu A, Hesler CB, Agellon LB, Mann C, Whitlock ME, Marcel YL, Milne RW, Koizumi J, Mabuchi H, Takeda R, Tall AR: Molecular basis of lipid transfer protein deficiency in a family with increased high-density lipoproteins. Nature. 1989, 342: 448-451. 10.1038/342448a0.

Inazu A, Jiang XC, Haraki T, Yagi K, Kamon N, Koizumi J, Mabuchi H, Takeda R, Takata K, Moriyama Y, Doi M, Tall A: Genetic cholesteryl ester transfer protein deficiency caused by two prevalent mutations as a major determinant of increased levels of high density lipoprotein cholesterol. J Clin Invest. 1994, 94: 1872-1882.

Utermann G: Apolipoprotein E polymorphism in health and disease. Am Heart J. 1987, 113: 433-440. 10.1016/0002-8703(87)90610-7.

Lehtinen S, Rantalaiho V, Wirta O, Pasternack A, Laippala P, Koivula T, Lehtimaki T: Apolipoprotein E gene polymorphism, hypercholesterolemia and glomerular filtration rate in type 2 diabetic subjects: a 9-year follow-up study. J Biomed Sci. 2003, 10: 260-5. 10.1159/000068712.

Horita K, Eto M, Makino I: Apolipoprotein E2, renal failure and lipid abnormalities in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Atherosclerosis. 1994, 107: 203-11. 10.1016/0021-9150(94)90021-3.

Eto M, Saito M, Okada M, Kume Y, Kawasaki F, Matsuda M, Yoneda M, Matsuki M, Takigami S, Kaku K: Apolipoprotein E genetic polymorphism, remnant lipoproteins, and nephropathy in type 2 diabetic patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002, 40: 243-51. 10.1053/ajkd.2002.34502.

American Diabetes association: Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2004, 27 (suppl 1): 5-10.

American Diabetes association: Screening for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004, 27 (suppl 1): 11-14.

Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF: A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988, 16: 1215-

Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS: Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma without use of preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972, 18: 499-502.

Fumeron F, Betoulle D, Luc G, Behague I, Ricard S, Poirier O, Jemaa R, Evans A, Arveiler D, Marques-Vidal P: Alcohol intake modulates the effect of a polymorphism of the cholesteryl ester transfer protein gene on plasma high density lipoprotein and the risk of myocardial infarction. J Clin Invest. 1995, 96: 1664-71.

Arashiro R, Katsuren K, Maung KK, Fukuyama S, Ohta T: Effect of a common mutation (D442G) of the cholesteryl ester transfer protein gene on lipids and lipoproteins in children. Pediatr Res. 2001, 50: 455-9.

Hixson JE, Vernier DT: Restriction isotyping of human apolipoprotein E by gene amplification and cleavage with HhaI. J Lipid Res. 1990, 31: 545-8.

Kuivenhoven JA, Jukema JW, Zwinderman AH, de Knijff P, McPherson R, Bruschke AV, Lie KI, Kastelein JJ: The role of a common variant of the cholesteryl ester transfer protein gene in the progression of coronary atherosclerosis. The Regression Growth Evaluation Statin Study Group. New Engl J Med. 1998, 338: 86-93. 10.1056/NEJM199801083380203.

Corbex M, Poirier O, Fumeron F, Betoulle D, Evans A, Ruidavets JB, Arveiler D, Luc G, Tiret L, Cambien F: Extensive association analysis between the CETP gene and coronary heart disease phenotypes reveals several putative functional polymorphisms and gene-environment interaction. Genet Epidemiol. 2000, 19: 64-80. 10.1002/1098-2272(200007)19:1<64::AID-GEPI5>3.0.CO;2-E.

Ordovas JM, Cupples LA, Corella D, Otvos JD, Osgood D, Martinez A, Lahoz C, Coltell O, Wilson PW, Schaefer EJ: Association of cholesteryl ester transfer protein-TaqIB polymorphism with variations in lipoprotein subclasses and coronary heart disease risk: the Framingham study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000, 20: 1323-1329.

Corella D, Saiz C, Guillen M, Portoles O, Mulet F, Gonzalez JI, Ordovas JM: Association of TaqIB polymorphism in the cholesteryl ester transfer protein gene with plasma lipid levels in a healthy spanish population. Atherosclerosis. 2000, 152: 367-376. 10.1016/S0021-9150(99)00477-3.

Chaaba R, Hammami S, Attia N, Smaoui M, Masmoudi AS, Mahjoub S, Ben Hamda K, Hammami M: Association of plasma cholesteryl ester transfer protein activity and polymorphism with coronary artery disease extent in Tunisian type II diabetic patients. Clin Biochem. 2005, 38: 373-8. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2004.12.011.

Boekholdt SM, Sacks FM, Jukema JW, Shepherd J, Freeman DJ, McMahon AD, Cambien F, Nicaud V, de Grooth GJ, Talmud PJ, Humphries SE, Miller GJ, Eiriksdottir G, Gudnason V, Kauma H, Kakko S, Savolainen MJ, Arca M, Montali A, Liu S, Lanz HJ, Zwinderman AH, Kuivenhoven JA, Kastelein JJ: Cholesteryl ester transfer protein TaqIB variant, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, cardiovascular risk, and efficacy of pravastatin treatment: individual patient meta-analysis of 13,677 subjects. Circulation. 2005, 111: 278-87. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000153341.46271.40.

Meguro S, Takei I, Murata M, Hirose H, Takei N, Mitsuyoshi Y, Ishii K, Oguchi S, Shinohara J, Takeshita E, Watanabe K, Saruta T: Cholesteryl ester transfer protein polymorphism associated with macroangiopathy in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Atherosclerosis. 2001, 156: 151-156. 10.1016/S0021-9150(00)00606-7.

Kakko S, Tamminen M, Paivansalo M, Kauma H, Rantala AO, Lilja M, Reunanen A, Kesaniemi YA, Savolainen MJ: Variation at the cholesteryl ester transfer protein gene in relation to plasma high density lipoproteins cholesterol levels and carotid intima-media thickness. Eur J Clin Invest. 2001, 31: 593-602. 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2001.00859.x.

Goto A, Sasai K, Suzuki S, Fukutomi T, Ito S, Matsushita T, Okamoto M, Suzuki T, Itoh M, Okumura-Noji K, Yokoyama S: Cholesteryl ester transfer protein and atherosclerosis in Japanese subjects: a study based on coronary angiography. Atherosclerosis. 2001, 159: 153-163. 10.1016/S0021-9150(01)00476-2.

Tai ES, Ordovas JM, Corella D, Deurenberg-Yap M, Chan E, Adiconis X, Chew SK, Loh LM, Tan CE: The Taq IB and -629C>A polymorphisms at the cholesteryl ester transfer protein locus: associations with lipid levels in a multiethnic population. The 1998 Singapore National Health Survey. Clin Genet. 2003, 63: 19-30. 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2003.630104.x.

Relvas WG, Izar MC, Helfenstein T, Fonseca MI, Colovati M, Oliveira A, Ihara SS, Han SW, Las Casas AA, Fonseca FA: Relationship between gene polymorphisms and prevalence of myocardial infarction among diabetic and non-diabetic subjects. Atherosclerosis. 2005, 178: 101-5. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.05.025.

Funke H, Wiebusch H, Fuer L, Muntoni S, Schulte H, Assmann G: Identification of mutations in the cholesteryl ester transfer protein in Europeans with elevated high density lipoprotein cholesterol [abstract]. Circulation. 1994, 90: I-241.

Kuivenhoven JA, de Knijff P, Boer JM, Smalheer HA, Botma GJ, Seidell JC, Kastelein JJ, Pritchard PH: Heterogeneity at the CETP gene locus. Influence on plasma CETP concentrations and HDL cholesterol levels. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997, 17: 560-568.

Gudnason V, Kakko S, Nicaud V, Savolainen MJ, Kesaniemi YA, Tahvanainen E, Humphries S: Cholesteryl ester transfer protein gene effect on CETP activity and plasma high-density lipoprotein in European populations. The EARS Group. Eur J Clin Invest. 1999, 29: 116-128. 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1999.00412.x.

Zhong S, Sharp DS, Grove JS, Bruce C, Yano K, Curb JD, Tall AR: Increased coronary heart disease in Japanese-American men with mutation in the cholesteryl ester transfer protein gene despite increased HDL levels. J Clin Invest. 1996, 97: 2917-23.

Song GJ, Han GH, Chae JJ, Namkoong Y, Lee HK, Park YB, Lee CC: The effects of the cholesterol ester transfer protein gene and environmental factors on the plasma high density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in the Korean population. Mol Cells. 1997, 7: 615-619.

Choi HS, Park JB, Han KO, Yim CH, Jung HY, Jang HC, Yoon HK, Cho DH, Shin HH, Han IK: A common mutation in cholesteryl ester transfer protein gene and plasma HDL cholesterol level before and after hormone replacement therapy in Korean postmenopausal women. Korean J Intern Med. 2002, 17: 83-87.

Freeman DJ, Samani NJ, Wilson V, McMahon AD, Braund PS, Cheng S, Caslake MJ, Packard CJ, Gaffney D: A polymorphism of the cholesteryl ester transfer protein gene predicts cardiovascular events in non-smokers in the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study. Eur Heart J. 2003, 24: 1833-1842. 10.1016/j.ehj.2003.07.001.

Inazu A, Koizumi J, Mabuchi H: Cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) deficiency and increased HDL cholesterol levels (hyperalphalipoproteinemia). Rinsho Byori. 1996, 44: 322-326.

Hui SP: Frequency and effect on plasma lipoprotein metabolism of a mutation in the cholesteryl ester transfer protein gene in the Chinese. Hokkaido Igaku Zasshi. 1997, 72: 319-327.

Hsu LA, Ko YL, Hsu KH, Ko YH, Lee YS: Genetic variations in the cholesteryl ester transfer protein gene and high density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in Taiwanese Chinese. Hum Genet. 2002, 110: 57-63. 10.1007/s00439-001-0640-z.

Zhuang Y, Wang J, Qiang H, Li Y, Liu X, Li L, Chen G: Cholesteryl ester transfer protein levels and gene deficiency in Chinese patients with cardio-cerebrovascular diseases. Chin Med J (Engl). 2002, 115: 371-374.

Zheng KQ, Zhang SZ, Zhang KL, Zhang L, He Y, Kong XD, Sun Y, Su ZG: Study on the association of cholesteryl ester transfer protein gene mutations with the susceptibility to coronary atherosclerotic heart disease. Zhonghua Yi Xue Yi Chuan Xue Za Zhi. 2003, 20: 23-26.

Eto M, Horita K, Morikawa A, Nakata H, Okada M, Saito M, Nomura M, Abiko A, Iwashima Y, Ikoda A: Increased frequency of apolipoprotein epsilon 2 allele in non-insulin dependent diabetic (NIDDM) patients with nephropathy. Clin Genet. 1995, 48: 288-92.

Zhang X, Liu B, Bai H, Tian H, Wu Z, Zhang R, Fang D, Zhang R, Xu Y, Yao J, Ren : Study on apolipoprotein E gene polymorphism in Chinese type 2 diabetes mellitus. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2003, 34: 75-7.

Araki S, Koya D, Makiishi T, Sugimoto T, Isono M, Kikkawa R, Kashiwagi A, Haneda M: APOE polymorphism and the progression of diabetic nephropathy in Japanese subjects with type 2 diabetes: results of a prospective observational follow-up study. Diabetes Care. 2003, 26: 2416-20.

Powell DS, Maksoud H, Charge SB, Moffitt JH, Desai M, Da Silva Fihlo RL, Hattersley AT, Stratton IM, Matthews DR, Levy JC, Clark A: Apolipoprotein E genotype, islet amyloid deposition and severity of Type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2003, 60: 105-10. 10.1016/S0168-8227(02)00281-4.

Kim JH, Lee EJ, Kwon OH: Apolipoprotein E genotyping and phenotyping in type II diabetes mellitus patients with hypertriglyceridemia. Clin Biochem. 1997, 30: 47-52. 10.1016/S0009-9120(96)00130-0.

Kamboh MI, Aston CE, Hamman RF: The relationship of APOE polymorphism and cholesterol levels in normoglycemic and diabetic subjects in a biethnic population from the San Luis Valley, Colorado. Atherosclerosis. 1995, 112: 145-59. 10.1016/0021-9150(94)05409-C.

Oh JY, Barrett-Connor E, Rancho Bernardo Study Group: Apolipoprotein E polymorphism and lipid levels differ by gender and family history of diabetes: the Rancho Bernardo Study. Clin Genet. 2001, 60: 132-7. 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2001.600207.x.

Inamdar PA, Kelkar SM, Devasagayam TP, Bapat MM: Apolipoprotein E polymorphism in non-insulin-dependent diabetics of Mumbai, India and its effect on plasma lipids and lipoproteins. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2000, 47: 217-23. 10.1016/S0168-8227(99)00126-6.

Wu JH, Lee YT, Hsu HC, Hsieh LL: Influence of CETP gene variation on plasma lipid levels and coronary heart disease: a survey in Taiwan. Atherosclerosis. 2001, 159: 451-8. 10.1016/S0021-9150(01)00524-X.

Jap TS, Wu YC, Tso YC, Chiu C: A novel mutation in the intron 1 splice donor site of the cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP) gene as a cause of hyperalphalipoproteinemia. Metabolism. 2000, 51: 394-7. 10.1053/meta.2002.30527.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6823/5/7/prepub

Acknowledgements

Dr S. Bhattacharya is grateful to Vice-Chancellor of King George Medical University Lucknow for granting study leave to avail DBT training fellowship at SGPGIMS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

MD carried out the experimentation and data analysis. SB participated in clinical characterization of patients and experimentation. BM participated in the design of the study and coordination.

Manjusha Dixit, Sandeep Bhattacharya contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Dixit, M., Bhattacharya, S. & Mittal, B. Association of CETP TaqI and APOE polymorphisms with type II diabetes mellitus in North Indians: a case control study. BMC Endocr Disord 5, 7 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6823-5-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6823-5-7