Abstract

Background

Vitiligo is a hypopigmentation disorder affecting 1 to 4% of the world population. Fifty percent of cases appear before the age of 20 years old, and the disfigurement results in psychiatric morbidity in 16 to 35% of those affected.

Methods

Our objective was to complete a comprehensive, systematic review of the published scientific literature to identify natural health products (NHP) such as vitamins, herbs and other supplements that may have efficacy in the treatment of vitiligo. We searched eight databases including MEDLINE and EMBASE for vitiligo, leucoderma, and various NHP terms. Prospective controlled clinical human trials were identified and assessed for quality.

Results

Fifteen clinical trials were identified, and organized into four categories based on the NHP used for treatment. 1) L-phenylalanine monotherapy was assessed in one trial, and as an adjuvant to phototherapy in three trials. All reported beneficial effects. 2) Three clinical trials utilized different traditional Chinese medicine products. Although each traditional Chinese medicine trial reported benefit in the active groups, the quality of the trials was poor. 3) Six trials investigated the use of plants in the treatment of vitiligo, four using plants as photosensitizing agents. The studies provide weak evidence that photosensitizing plants can be effective in conjunction with phototherapy, and moderate evidence that Ginkgo biloba monotherapy can be useful for vitiligo. 4) Two clinical trials investigated the use of vitamins in the therapy of vitiligo. One tested oral cobalamin with folic acid, and found no significant improvement over control. Another trial combined vitamin E with phototherapy and reported significantly better repigmentation over phototherapy only. It was not possible to pool the data from any studies for meta-analytic purposes due to the wide difference in outcome measures and poor quality ofreporting.

Conclusion

Reports investigating the efficacy of NHPs for vitiligo exist, but are of poor methodological quality and contain significant reporting flaws. L-phenylalanine used with phototherapy, and oral Ginkgo biloba as monotherapy show promise and warrant further investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Vitiligo is a hypopigmentation disorder where the loss of functioning melanocytes causes the appearance of white patches on the skin. Vitiligo affects 1% of the world population [1], but the prevalence has been reported as high as 4% in some South Asian, Mexican and American populations [2, 3]. Vitiligo can develop at any age, but several studies report that 50% of cases appear before the age of 20 [4–6]. Barona found that in patients with unilateral vitiligo the mean age at onset was 16.3 years (95% CI: 12 to 19 years), compared to 24.8 years (95% CI: 22 to 28 years) in patients with bilateral vitiligo [7].

Sixteen to 35% of patients with vitiligo experience significant psychiatric morbidity [8]. Depression (10%), dysthymia (7–9%), sleep disturbances (20%), suicidal thoughts (10%), suicidal attempts (3.3%) and anxiety (3.3%) have been found in those affected with vitiligo [8]. Vitiligo can also lead to difficulties in forming relationships, avoidance of certain social situations, and difficulties in sexual relationships [9]. Vitiligo can be confused with leprosy, which also causes loss of pigment, thus further stigmatizing patients [10].

Several systematic reviews assessing the clinical efficacy of topical corticosteroids, narrowband ultraviolet light B (UVB), psoralen with ultraviolet light A exposure (PUVA), calcipotriol, l-phenylalanine, topical immunomodulators (tacrolimus and pimecrolimus), excimer laser, and surgical therapy in the management of symptoms associated with vitiligo have recently been published, including in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) and by the Cochrane Collaboration [1, 11, 12]. These reviews conclude that there is some evidence that topical steroids are of benefit, but report concerns with long term side effects of topical steroids. The review authors also report some evidence for the efficacy of phototherapy (UVA or UVB) as a monotherapy, or combined with psoralens or calcipotriol. However, concerns are raised about side effects such as phototoxic reactions, blistering, and lack of data on long term skin cancer risk. All three systematic reviews conclude that use of topical immunomondulators shows promise, but that further evaluation is needed. In addition, the systematic review by Whitton [1] performed for the Chochrane collaboration and the systematic review published by Forschner [11] in JAMA indicate that L-phenylalanine use with phototherapy appears promising, but that more research is necessary before firm conclusions can be drawn.

Although many clinical trials examining the use of natural health product (NHP) interventions (e.g., vitamins, minerals, herbal medicines and other supplements) for vitiligo have been published, we were unable to find any systematic reviews of these. Here we report the results of a systematic review of controlled clinical trials investigating the efficacy of NHPs in the treatment of vitiligo.

Methods

Our objective was to complete a comprehensive, systematic review of the published scientific literature to identify NHPs that may have efficacy in the treatment of vitiligo. The databases and search terms used are listed in Table 1. All databases were searched for all available years up to August 27, 2007. The first two items (vitiligo, leucoderma) were searched individually in each database and combined together using the "OR" boolean. All search terms except the first two (vitiligo, leucoderma) were searched individually in each database and combined together using the "OR" boolean. The results from the searches of the first two bullets were then combined with the rest of the search terms by utilizing the "AND" boolean.

The resulting list was assessed for inclusion and exclusion criteria based on title and abstract. Full reports of the studies that matched the inclusion criteria were collected, translated where necessary, and re-assessed to make a final decision regarding inclusion or exclusion. The assessment process was completed by OS, in consultation with HB.

This systematic review included prospective controlled clinical human trials. Randomization was not a requirement for inclusion in the review. Only studies which used NHPs as defined by Health Canada [13] were selected. Essentially, Health Canada defines any compound found in nature that is used for health purposes as a NHP including: vitamins, minerals, and any product derived from a plant, animal, fungi or algae. In addition, the patients in the trials must have been diagnosed with any form of vitiligo as defined by Merck [14]. The Merck manual defines vitiligo as a loss of skin melanocytes leading to sharply demarcated depigmented areas, often systematically spread. Diagnosis is made by examination, and skin lesions are accentuated under Wood's light. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were determined a priori. We included trials published in any language, treating males or females of any age and skin type. Epidemiological association studies, and publications where the full study report was not available were excluded.

The included trials were assessed for design quality using the Jadad scale [15]. Based on the Jadad scale, one point is assigned if the study is described as randomized; one point is given if the study is described as double blind, and one point is awarded if there is a description of withdrawals and dropouts in the report. Additionally, one point is awarded if the randomization method was described and is appropriate (e.g., random number tables or computer generated sequence), and one final point is awarded if the double blinding method was described and is appropriate. If the randomization or double blinding methods were inappropriate, one point for each inappropriate method is deducted. The maximum score is 5, indicating a high quality trial. Previous reviews report a mean Jadad score of 3.12 for herbal trials [16], and a mean Jadad score of 3.2 for trials of conventional medicine [17]. A study by Klassen directly comparing the quality of CAM (complementary and alternative medicine) and conventional medicine trials reports a median Jadad score of 3 for CAM and 2 for conventional medicine trials, citing no significant difference between the two [18]. These findings are consistent with another recently published study comparing the quality of placebo-controlled trials of western phytotherapy with conventional medicine, which concluded that the quality of phytotherapy trials was superior to those of conventional medicine [19].

In addition to the information required to calculate the Jadad score, the following information was extracted from each paper: study design, number of participants, compliance, inclusion and exclusion criteria, intervention, outcome measure, results and adverse events. This information was collected to facilitate comparison with the Cochrane Collaboration's review of conventional biomedical vitiligo treatments [1].

Results

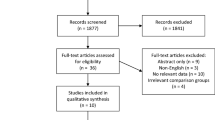

The initial search of NHP search terms and Vitiligo resulted in 986 citations. A manual review of titles and abstracts was conducted to identify studies appearing to meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria which resulted in 47 articles. The full text of these articles was obtained and reviewed. Studies without a control group, epidemiological reports, and incomplete reports were discarded. This process resulted in 15 articles that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Details of these studies are summarized in Table 2.

Of the 15 trials included in this review 11 were published in English, three in Chinese, and one in French. Trial reports published in Polish, Russian, German, Spanish and Italian were reviewed during the second stage of data collection; however, these were either incomplete, did not involve NHPs, or were uncontrolled and therefore did not meet our inclusion criteria. Of the trials included in this review, ten studied NHPs as an adjunct to UVA or UVB, and five investigated NHPs as the primary treatment. We group the clinical trials into four broad categories of NHP interventions: L-phenylalanine, traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) products, herbs, and vitamins.

The most commonly studied intervention was L-phenylalanine, assessed in three trials as an adjuvant to UVA or UVB phototherapy [20, 21] (Siddiqui references two trials in one paper), and in one trial with other agents but without phototherapy [22]. At doses ranging from 50 mg/kg to 100 mg/kg for 6 to 18 months, all trials reported beneficial effects. The studies recruited from 19 to 149 patients. Two of the studies had a Jadad score of 0, and two had a Jadad score of 3. The main problems were lack of randomization and poor control in two studies, high participant dropout in another trial, and inconsistent outcome measures. It is not possible to pool the data from the studies for meta-analytic purposes due to the wide differences in outcome measures. Overall there is moderate evidence that L-phenylalanine has efficacy as an adjunctive agent to phototherapy. Additional controlled research that focuses on L-phenylalanine in conjunction with UVA or UVB phototherapy is necessary to confirm these preliminary findings.

Three trials used traditional Chinese medicinal herbs for the treatment of vitiligo [23–25]. Each clinical trial used different remedies, some given by themselves, or in conjunction with phototherapy or sun tan advice. Specifically, Liu used a Xiaobai mixture containing walnut, red flower, black sesame, black beans, zhi bei fu ping, lu lu tong, and plums; details of the products investigated were not provided for the other two trials. All three trials compared the NHP intervention to conventional biomedical treatments of vitiligo (phototherapy, corticosteroids, or psoralen) in the control group. The studies ranged from 74 to 329 patients and 2–3 months. Even though two of the studies are relatively large (329 and 232 participants), participants were divided into multiple groups. No further details of group allocation are provided. All three trials indicate positive results for the NHP intervention. All three trials received a Jadad score of 1. Varying and poorly described treatments, small treatment group size, and inconsistent outcome measures were the main problems with the studies. It is not possible to pool the data from the studies for meta-analytic purposes due to the varying treatments and differences in outcome measures. Overall, there is weak evidence that some traditional Chinese medicinal herbs may be useful for the treatment of vitiligo. None of the treatments' effects have been replicated and overall the studies are of poor methodological quality.

Six trials investigated the use of plants in the treatment of vitiligo. Four of these trials utilized plants as photosensitizing agents (Picorrhiza kurroa, a khellin extract, and two Polypodium leucotomos) [26–29] all given orally in conjunction with UVA or UVB phototherapy; one investigated the use of oral Ginkgo biloba by itself (40 mg TID) [2]; and one investigated the topical use of an extract of Cucumis melo [30]. Treatments lasted from 3 to 12 months, and the studies were small, ranging from 9 to 50 participants. Only one trial by Middelkamp-Hup utilising Polypodium leucotomos was of good quality, scoring 5 on the Jadad scale, while the quality of the other four trials was poor, reflected by Jadad scores ranging from 0 to 2. The main problems with the studies were the small sample size, poor study design, and inconsistent outcome measures. Overall, there is weak evidence that photosensitizing plants can be effective in conjunction with phototherapy, and moderate evidence that Ginkgo biloba by itself can be useful for vitiligo. Cucumis melo treatment was not found to be statistically significant over placebo cream. Additional research to confirm these preliminary trials is necessary.

Two trials investigated the use of vitamins as adjuvants to UVA or UVB phototherapy [31, 32]. Oral cobalamin (1000 mcg BID) and folic acid (5 mg BID) were given in one trial, and oral vitamin E was given in another (900 IU, type of vitamin E not specified). After 12 months of treatment the cobalamin and folic acid study reported no significant difference compared to a phototherapy control. On the other hand, 6 months of treatment with combined vitamin E and phototherapy achieved significantly better repigmentation than phototherapy only. The studies were small, ranging from 27 to 30 participants, and neither had a Jadad score greater than 2. There was a lack of statistical information, and inconsistent outcome measures were used. Overall, there is no evidence for using oral cobalamin and folic acid with phototherapy for the treatment of vitiligo, while the evidence for vitamin E as an adjunct to phototherapy is weak.

Only five trials discussed adverse events, the most common of which were erythema, pruritis, and nausea. Erythema was reported in studies utilizing phototherapy. Pruritis was reported in trials using metoxsalen with Picorrhiza kurroa and Polypodium leucotomos with phototherapy. Nausea and gastrointestinal complaints were reported in trials utilizing Ginkgo biloba, P. leucotomos with phototherapy, and Vitamin E with phototherapy. It is difficult to ascertain whether the NHPs or their concomitant treatments caused these adverse reactions. All reported adverse reactions were minor. Most studies did not adequately report adverse events, and the small sample size of the trials makes generalizations difficult. A complete list of adverse events reported is in Table 3.

Discussion

Most of the clinical trials identified were uncontrolled, and thus could not be included in this review. Of the controlled clinical trials reviewed, most were of poor methodological quality with only one trial receiving a Jadad score of four or greater, and 13 receiving a score of three or less. Only five trials could be classified as randomized controlled trials. We found that most of the studies were poorly reported, often lacking information on dosage frequency, dosage strength, participant withdrawal, statistical analyses and randomization. Few were double blind, and there is no mention of compliance in any report. These findings are consistent with the poor quality of vitiligo trials of conventional biomedical treatments, as discussed in the systematic review by Whitton [1] for the Cochrane collaboration.

Whitton [1] also expressed concern with the lack of common, reliable outcome parameters and the variation of methods for scoring repigmentation. Our findings mirror this problem. We found that most NHP trials set several repigmentation ranges and measured the number of participants falling into each category at the end of treatment. These repigmentation ranges seem to be arbitrary and vary between trials, making data pooling and comparing results across treatments difficult.

Further clinical research in the treatment of vitiligo is necessary. Two areas are particularly intriguing. First, well designed clinical trials should attempt to replicate the studies utilizing L-phenylalanine in conjunction with phototherapy treatment. Several small clinical trials published so far provide positive results consistently with replication, but larger more definitive trials are necessary. Second, the use of Ginkgo biloba alone for the treatment of vitiligo holds potential promise. The use of Gingko biloba without phototherapy is likely to avoid the adverse reactions and unknown long term risks associated with phototherapy. If effective, Ginko biloba would also be a less costly and easier treatment for vitiligo. Parsaud's trial is methodologically sound, and provides promising results. However, one published trial is not enough evidence to impact clinical practice. The need to find a safe and effective treatment is particularly important with vitiligo, where up to 50% of cases develop in the paediatric population; at a time when the condition has the greatest impact on psychological development.

The poor quality of vitiligo trials has been recognized. Several validated vitiligo outcome measures have recently been suggested and should be utilized in future clinical trials. One such measure is the Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (VASI) which takes into account both the lesion area and the intensity of depigmentation [33]. An even more precise measurement of vitiligo has been described by the Vitiligo European Task Force [34]. The first component summarizes relevant disease and patient information, while the second component is an assessment system evaluating the extent of depigmentation using the rule of 9's. (The rule of 9's is a quick way of estimating the affected skin's surface area, where the palm is 1% of the surface area; arms, and face & scalp are each 9% of the surface area; and legs, the back, and front are 18% each). In addition, the disease is staged based on cutaneous and hair pigmentation of the largest lesion in each body area, and ranked on a scale from 0–4. Assessment of spreading is based on a Wood's lamp examination of the largest lesion in each body area. The clinical use of this system has been evaluated by several European University clinics, and has showed good internal reliability [34]. Future trials should also differentiate and evaluate vitiligo treatments among their ability to induce stability, thus arresting further depigmentation, and repigmentation.

Our review is limited by the poor quality of the clinical trials. While there are many published clinical trials using NHPs for the treatment of vitiligo, there is a lack of randomized clinical trials. The different NHPs tested, and the variability of the outcome measures make it impossible to pool any data. Many trials seem to be explorative trials, with no published follow up investigations replicating the findings.

Conclusion

Reports investigating the efficacy of NHPs for vitiligo exist, but are of poor methodological quality and contain significant reporting flaws. Most trials use NHPs as an adjunct to UVA or UVB phototherapy. There are few controlled trials assessing efficacy of NHPs for vitiligo, but those that have been published generally show weakly positive outcomes with few adverse reactions. L-phenylalanine used with phototherapy shows promise. The use of oral Ginkgo biloba as monotherapy for vitiligo is also promising. Ginkgo's apparent efficacy without the need for phototherapy, thus eliminating the adverse events inherent with phototherapy make it a therapeutic option worth investigating. Further high quality investigations into the use of NHPs in the treatment of vitiligo, particularly L-phenylalanine and Ginkgo biloba are needed.

Abbreviations

- CAM:

-

complementary and alternative medicine

- JAMA:

-

the Journal of the American Medical Association

- NHP:

-

natural health product

- PUVA:

-

psoralen with ultra violet light A

- TCM:

-

traditional Chinese medicine

- UVB:

-

ultra violet light B.

References

Whitton ME, Ashcroft DM, Barrett CW, Gonzalez U: Interventions for vitiligo [Systematic Review]. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007;(3)

Parsad D, Pandhi R, Juneja A: Effectiveness of oral Ginkgo biloba in treating limited, slowly spreading vitiligo. Clinical & Experimental Dermatology 2003,28(3):285–287. 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2003.01207.x

Sehgal VN, Srivastava G: Vitiligo: compendium of clinico-epidemilogical features. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2007,73(3):149–156.

Halder RMMD, Nootheti PKMD: Ethnic skin disorders overview. [Miscellaneous]. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology June 2003;48(6 (Part 2)) Supplement:S143-S148

Behl PN, Bhatia RK: 400 cases of vitiligo - A clinicotherapeutic analysis. Indian J Dermatol 1971, 17: 51–53.

Mehta HR, Shah KC, Theodore C: Epidemiological study of vitiligo in Surat area, South Gujarat. Indian Journal of Medical Research 1973, 61: 145–154.

Barona M, Arrunategui A, Falabella R, Alzate A: An epidemiologic case-control study in a population with vitiligo. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 1995,33(4):621–625. 10.1016/0190-9622(95)91282-7

Ongenae K, Beelaert L, Van Geel N, Naeyaert JM: Psychosocial effects of vitiligo. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2006,20(1):1–8. 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2005.01369.x

Porter J, Beuf AH, Nordlund JJ, Lerner AB: The effect of vitiligo on sexual relationships. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 1990,22(1 Pt 1):221–222.

Porter J, Beuf AH, Nordlund JJ, AB. L: Response to cosmetic disfigurement: Patients with vitiligo. Cutis 1987,39((6)):493–494.

Forschner T, Buchholtz S, Stockfleth E: Current state of vitiligo therapy - evidence based analysis of the literature. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2007,5(6):467–475. 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2007.06280.x

Grimes PEMD: New Insights and New Therapies in Vitiligo. [Miscellaneous Article]. JAMA February 9, 2005;293(6):730–735

Canada H[http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/prodnatur/index-eng.php]

Beers MH, Berkow R: The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy. 1999, 835–836.

Jadad A, Moore A, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds J, Gavaghan D, McQuay D: Assessing the Quality of Reports of Randomized Clinical Trials: Is Blinding Necessary? Controlled Clinical Trials 1996, 17: 1–12. 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4

Gagnier JJ, DeMelo J, Boon H, Rochon P, Bombardier C: Quality of Reporting of Randomized Controlled Trials of Herbal Medicine Interventions. The American Journal of Medicine 2006,119(9):800.e1–11. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.02.006

Peloso PM, Gross AR, Haines TA, Trinh K, Goldsmith CH, Aker P: Medicinal and injection therapies for mechanical neck disorders: a Cochrane systematic review. Journal of Rheumatology 2006,33(5):957–967.

Klassen T, Pham B, Lawson M, Moher D: For randomized controlled trials, the quality of reports of complementary and alternative medicine was as good as reports of conventional medicine. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2005, 58: 763–768. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.08.020

Nartey L, Huwiler-Muntener K, Shang A, Liewald K, Juni P, Egger M: Matched-pair study showed higher quality of placebo-controlled trials in Western phytotherapy than conventional medicine. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2007, 787–794.

Cormane RH, Siddiqui AH, Westerhof W, Schutgens RB: Phenylalanine and UVA light for the treatment of vitiligo. Archives of Dermatological Research 1985,277(2):126–130. 10.1007/BF00414110

Siddiqui AH, Stolk LML, Bhaggoe R, Hu R, Schutgens RBH, Westerhof W: L-Phenylalanine and UVA irradiation in the treatment of vitiligo. Dermatology 1994,188(3):215–218.

Rojas-Urdaneta JE, Poleo-Romero AG: [Evaluation of an antioxidant and mitochondria-stimulating cream formula on the skin of patients with stable common vitiligo]. [Spanish]. Investigacion Clinica 2007,48(1):21–31.

Cheng YQ, Shi DR: [Clinical analysis of the effects of a combined therapy with Vernonia anthelmintica and others on 329 cases of vitiligo]. [Chinese]. Chung Hsi i Chieh Ho Tsa Chih Chinese Journal of Modern Developments in Traditional Medicine 7(6):350–351.

Liu ZJ, Xiang YP: [Clinical observation on treatment of vitiligo with xiaobai mixture]. [Chinese]. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi Zhongguo Zhongxiyi Jiehe Zazhi/Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional & Western Medicine/Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Xue Hui, Zhongguo Zhong Yi Yan Jiu Yuan Zhu Ban 2003,23(8):596–598.

Jin Qx, M. WJ, D. ZS, Y. GM, P. WH, Y. SS: Clinical efficacy observation of combined treatment with Chinese traditional medicine and western medicine for 407 cases of vitiligo (Chinese). Journal of Clinical Dermatology 1983,12(1):9–11.

Bedi KL, Zutshi U, Chopra CL, Amla V: Picrorhiza kurroa, an Ayurvedic herb, may potentiate photochemotherapy in vitiligo. J Ethnopharmacol 1989,27(3):347–352. 10.1016/0378-8741(89)90009-3

Valkova S, Trashlieva M, Christova P: Treatment of vitiligo with local khellin and UVA: comparison with systemic PUVA. [Report]. Clin Exp Dermatol 2004,29(2):180–184. 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2004.01462.x

Middelkamp-Hup MA, Bos JD, Rius-diaz F, Gonzalez S, Westerhof W: Treatment of vitiligo vulgaris with narrow-band UVB and oral Polypodium leucotomos extract: a randomized double blind placebo-controlled study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2007,21(7):942–950. 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.02132.x

anonymous: Systemic immunomodulatory effects of Polypodium leucotomos as an adjuvant to PUVA therapy in generalized vitiligo: a pilot study. Journal of Dermatological Science 2006, 213–216.

Khemis A, Ortonne JP: Comparative study of vegetable extracts possessing active superoxide dismutase and catalase (Vitix) plus selective UVB phototherapy versus an excipient plus selective UVB phototherapy in the treatment of common vitiligo. [French]. Nouvelles Dermatologiques 2004,23(1):45–46.

Tjioe M, Gerritsen MJ, Juhlin L, van de Kerkhof PC: Treatment of vitiligo vulgaris with narrow band UVB (311 nm) for one year and the effect of addition of folic acid and vitamin B12.[erratum appears in Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82(6):485.]. Acta Dermato-Venereologica 2002,82(5):369–372. 10.1080/000155502320624113

Akyol M, Celik VK, Ozcelik S, Polat M, Marufihah M, Atalay A: The effects of vitamin E on the skin lipid peroxidation and the clinical improvement in vitiligo patients treated with PUVA. European Journal of Dermatology 2002,12(1):24–26.

Hamzavi I, Jain H, McLean D, Shapiro J, Haishan Z, Lui H: Parametric Modeling of Narrowband UVB Phototherapy for Vitiligo Using a Novel Quantitative Tool. Archives of Dermatology 2004, 140: 677–683. 10.1001/archderm.140.6.677

Taieb A, Picardo M: The definition and assessment of vitiligo: a consensus report of the Vitiligo European Task Force. Pigment Cell Research 2007, 20: 27–35. 10.1111/j.1600-0749.2006.00355.x

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-5945/8/2/prepub

Acknowledgements

Translators: Vickie Chang, Kosta Cvijovic, Kathy Szczurko, Svitlana Yurchenko, Rishma Walji.

Funding: During the duration of this project Orest Szczurko received a Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Paediatrics Masters Scholarship from the Sick Kids Foundation; Heather Boon was funded as a Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

OS conceived of the study, carried out the data collection and review, drafted the manuscript and approved the final submitted version. HSB conceived of the study, guided the design, helped to resolve methodological concerns, critically revised the manuscript and approved the final submitted version.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Szczurko, O., Boon, H.S. A systematic review of natural health product treatment for vitiligo. BMC Dermatol 8, 2 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-5945-8-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-5945-8-2