Abstract

Background

Melanoma is the fastest growing tumor of the skin, which disproportionately affects younger and middle-aged adults. As melanomas are visible, recognizable, and highly curable while in early stages, early diagnosis is one of the most effective measures to decrease melanoma-related mortality. Skin self-examination results in earlier detection and removal of the melanoma. Due to the elevated risk of survivors for developing subsequent melanomas, monthly self-exams are strongly recommended as part of follow-up care. Yet, only a minority of high-risk individuals practices systematic and regular self-exams. This can be improved through patient education. However, dermatological education is effective only in about 50% of the cases and little is known about those who do not respond. In the current literature, psychosocial variables like distress, coping with cancer, as well as partner and physician support are widely neglected in relation to the practice of skin self-examination, despite the fact that they have been shown to be essential for other health behaviors and for adherence to medical advice. Moreover, the current body of knowledge is compromised by the inconsistent conceptualization of SSE. The main objective of the current project is to examine psychosocial predictors of skin self-examination using on a rigorous and clinically sound methodology.

Methods/Design

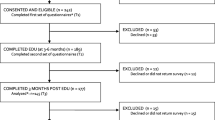

The longitudinal, mixed-method study examines key psychosocial variables related to the acquisition and to the long-term maintenance of skin self-examination in 200 patients with melanoma. Practice of self-exam behaviors is assessed at 3 and 12 months after receiving an educational intervention designed based on best-practice standards. Examined predictors of skin self-exam behaviors include biological sex, perceived self-exam efficacy, distress, partner and physician support, and coping strategies. Qualitative analyses of semi-structured interviews will complement and enlighten the quantitative findings.

Discussion

The identification of short and long-term predictors of skin self-examination and an increased understanding of barriers will allow health care professionals to better address patient difficulties in adhering to this life-saving health behavior. Furthermore, the findings will enable the development and evaluation of evidence-based, comprehensive intervention strategies. Ultimately, these findings could impact a wide range of outreach programs and secondary prevention initiatives for other populations with increased melanoma risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Melanoma – prevalence, survival and risk factors

Cutaneous melanoma, which disproportionately affects younger and middle-aged adults, is the fastest growing skin tumor. It is the most common form of cancer in women aged 25–29 and is second only to breast cancer in women 30–34 years old. Approximately 60% of all melanomas occur before the age of 65 years [1–5]. Compared to most other cancers, which generally begin to metastasize when they reach a diameter of approximately 1 cm, melanomas can metastasize when they are only 1 mm in depth, which translates into a 1000-fold increase in inherent metastatic potential [6, 7]. Hence, the depth of a melanoma at diagnosis is the strongest individual predictor of survival as there are no effective therapies once the tumor has spread [8, 9].

Populations with an increased risk for developing melanoma include individuals previously diagnosed with melanoma, first-degree relatives of melanoma survivors, patients with non-melanoma skin cancer, and individuals with many or atypical moles [10–12]. A personal history of melanoma is associated with a life-long elevated risk for developing subsequent melanomas [12–14], with up to 11 of 100 melanoma patients developing a second melanoma, typically within 7 years of the first [15–18].

There is consensus within the clinical and scientific communities that 1) intervention strategies designed to reduce cutaneous melanoma-related mortality must focus on early diagnosis of pre-metastatic tumors [11], p. 50]; and that 2) the highest impact intervention strategies will target high-risk individuals [10–12, 19, 20]. Because melanoma is recognizable and highly curable when detected early, but increasingly therapy-resistant and lethal as the tumor progresses, secondary prevention interventions can have a significant impact on reducing mortality [12, 21–24]. Secondary prevention of melanoma involves early detection via clinical skin exams or skin self-exams [10, 25].

The importance of skin self-examination (SSE)

About 75% of melanomas are detected by patients themselves or by spouses, friends, or other lay persons [26–30]. Early detection programs have been proven successful for the general public and for high-risk populations. For example, a large-scale melanoma-screening program involving participant education on SSE significantly reduced melanoma-related mortality by decreasing the incidence of melanomas with a thickness greater than 0.75 mm [31]. Similarly, an Australian randomized controlled trial (RCT) found that a population screening program, which included a melanoma awareness campaign, led to a reduction in thickness of melanomas diagnosed during the campaign [32, 33]. A large-scale population-based case–control study found that SSE was significantly associated with decreased risk of secondary melanoma and of advanced disease, and that SSE reduced melanoma-related mortality by 63% [34]. In this study patients who conducted rigorous SSE, using mirrors to examine one’s back, presented with significantly thinner melanomas than participants who did not perform SSE. A subsequent study with 816 melanoma patients supported the benefits of SSE as early diagnosis was significantly related with the practice of SSE [27]. A prospective study including 2,008 patients diagnosed with stage I - IV melanoma demonstrated that early detection of recurrence results in a significant benefit regarding overall survival probability [19]. Finally, in a study with 1,062 melanoma patients (stages I & II) 19% of patients experienced a melanoma recurrence, which was most often self-detected and led directly to seeking early medical advice [35]. Self-detection, not physician detection, independently predicted survival in this study. Consequently, guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), an alliance of 21 of the world's leading cancer centers, state that upon completion of the melanoma staging and treatment procedures all patients with stage IA to stage IV melanomas should be advised to self-examine their skin monthly [36]. Dermatological and cancer associations also recommend the regular practice of SSE and provide education materials on SSE conduct for the general public [37–39].

In sum, there is evidence that individuals who perform SSE present for treatment of melanomas at an earlier disease phase, have 50% less advanced melanoma and demonstrate significantly lower melanoma-related mortality [10, 27, 34, 35]. Many melanoma survivors do not, however, practice regular SSE following their initial treatment. Thus, an important challenge is how to achieve better adherence to this practice [40–42].

Facilitating skin self-examination

Even though cutaneous melanoma are readily visible on the skin surface and it is well-known that SSEs are related to better prognosis [32, 40, 41, 43, 44], most melanoma survivors do not perform systematic skin exams regularly [27, 34, 45, 46]. These observations have prompted research efforts to determine factors that may influence whether SSE is performed. Studies have shown, for instance, that having a personal or family history of skin cancer [40] is related to SSE. Demographic characteristics associated with SSE in the general population as well as in melanoma survivors include being female and having a higher level of education [27, 40, 45]. Unlike medical and demographic factors linked to SSE, which are not generally amenable to intervention, psychosocial and educational factors associated with SSE are potential targets of interventions to improve adherence to SSE instructions. Psychosocial and educational factors associated with SSE behaviors in melanoma survivors and other high-risk individuals include greater knowledge about melanoma and SSE [40, 47, 48], higher perceived susceptibility [40, 49], positive attitude towards SSE [40, 50], confidence in being able to perform an efficacious skin self-exam [40, 48–50], and being comfortable with having one’s partner assist in SSE [51, 52]. There is also preliminary evidence that the level of anxiety and the psychosocial strain resulting from a melanoma diagnosis affect self-exam practice [53]. Furthermore, being informed about SSE by a health care professional has been shown to be associated with SSE performance [45, 50, 54, 55], and several intervention studies in high-risk populations have reported improvement of SSE after standardized dermatological education [50, 56, 57]. However, improved SSE was documented for only 37% to 63% of the participants of these studies. Longer term effects of the dermatological education could not be determined as the follow-up period only ranged from 3 to 6 months in these studies. Furthermore, little is known about the patients who do not respond to dermatological education. Given that existing interventions to improve SSE have had limited success, it is important to better understand the degree to which patients adhere to SSE and to identify potentially modifiable factors that may influence adherence.

Limitations in existing evidence on psychosocial factors that may influence skin self-examination

Existing research on the association between psychosocial factors and SSE has been limited by how SSE has been operationalized, the limited inclusion of psychosocial variables, and the duration of studies. Estimates of SSE vary substantially depending on the way the information is elicited [25, 58, 59]. In some studies, this information has been collected by simply asking patients if they perform SSE without inquiring about the surface of skin examined or by inquiring ambiguously about frequency (e.g., rarely, sometimes, often) instead of using specific frequency categories (e.g., weekly, monthly, twice a year). As a result, rates of thorough SSE amongst melanoma survivors have ranged between 14% and 75% in different studies [30, 34, 45, 46, 60, 61]. Another limitation of previous research is that key psychological variables, such as psychological distress, coping and professional/personal support, are widely neglected in relation to SSE. First, while distress is a very well known risk factor for non-compliance with medical advice in general [62–64], only few studies assessing SSE included a measure of psychological distress [65, 66]. Second, while research has shown a higher prevalence of avoidant coping in skin cancer patients compared to both other cancer patients and healthy controls [67–72], only one study has examined the potential link between coping strategies and SSE in melanoma survivors [66]. Third, social support plays a crucial role in the psychological adjustment to living with the threat of melanoma [73, 74]. Research indicates that social support and coping are strongly interdependent in melanoma patients [69, 75]. Research has also shown that physician support is particularly important for melanoma patients, who indicated "trusting my doctors" and "following the medical advice exactly" as the two most frequent coping behaviors right after melanoma removal as well as during follow-up care [53]. Yet, to date only one study has examined coping behaviors in relation to SSE and physician support of SSE hasn’t been studied at all. Furthermore, research has shown that adherence to health behavior recommendation tends to decrease over longer time periods [62, 76]. However, previous studies documenting adherence to standardized SSE instructions only involved a 3 to 6-month follow-up assessment [50, 56, 57]. And lastly, while the combination of quantitative and qualitative methods can provide a more complete understanding of a phenomenon, mixed-method studies investigating the barriers and facilitators of SSE are lacking.

In sum, early detection of melanoma via SSE is effective for decreasing melanoma-related mortality. However, despite being recommended by clinical care guidelines, the majority of high-risk individuals do not practice SSE regularly or thoroughly. Rates of SSE can be improved through patient education, but little is known about those who do or do not respond optimally to medical advice on SSE. Acquiring knowledge on the best predictors of SSE practice will enable researchers and clinicians to design intervention protocols to target core issues in melanoma prevention, and, thus, hopefully, reduce mortality rates from secondary melanoma.

Study objectives

The main objective of this study is to identify short- and long-term predictors of SSE after providing best-practice clinical care, which includes medical advice on SSE, and to better understand challenges and opportunities for secondary prevention of melanoma in high-risk individuals. Specific objectives include:

-

(1)

To determine the extent of thorough SSE performance, defined in terms of completeness and frequency, at 3 months (i.e., Endpoint 1) and at 12 months (i.e., Endpoint 2) after receiving a standardized dermatological education session on SSE during melanoma follow-up care.

-

(2)

To identify psychosocial variables, including distress, coping strategies, and physician and partner support that are independently associated with thorough SSE at 3 months and at 12 months following a standardized dermatological education session.

-

(3)

To use qualitative methods to understand psychosocial factors, including physician and spousal support of SSE (or lack thereof), that help patients to affectively, cognitively and behaviorally adjust to the melanoma diagnosis and to the continuous need for SSE.

Hypotheses

-

1.

The prevalence of thorough SSE will be higher during the first 3 months than during month 9 to 12 after standardized dermatological education on SSE.

-

2.

Sex will predict SSE in terms of frequency and completeness. Psychosocial variables, including partner and physician support, psychological distress and coping strategies, will significantly predict additional variance in SSE performance assessed at 3 months and at 12 months after standardized dermatological education on SSE.

-

3.

Physician and spousal support of SSE will play an important role for the patient’s psychological adjustment to the melanoma diagnosis and to the continuous need for SSE.

Method/Design

Participants and procedures

Ethical approval of the study protocol was granted by the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine, McGill University (reference no. A11-B39-11B). Eligible patients will include English- and French-speaking adult patients with a confirmed diagnosis of melanoma who seek services at McGill teaching hospitals. Together, these hospitals treat over 400 new melanoma patients annually [77, 78]. Previous psychosocial studies with cancer populations at the same hospitals [30, 79, 80] and at other sites [81–92] reported participation rates between 57-86%, with a mean of 76%. Attrition rates range between 4% and 24% in psychosocial studies with an assessment up to 18 months after the treatment of patients with melanoma [56, 93] or other cancers [67, 82, 83, 94–97]. Enrollment will take place over 2 years and continue until 200 participants have completed the study. A sample of 200 participants provides sufficient statistical power for the analyses (for power estimates see section Data analysis). At all time points the questionnaires will be provided as paper-pencil versions. Participants will be asked up to 3 times to mail back questionnaires completed at home. Interviews will be conducted over the telephone.

During regular clinic visits up to 12 months after their melanoma diagnosis, i.e., at time 1 (T1), eligible patients will be advised by the clinical care staff about the opportunity to participate in the study. In addition, the study will be advertised through flyers and posters in the waiting room area, which will allow interested patients to proactively contact the research team about study participation. The research assistant will provide study information to interested patients, verify study eligibility and collect written, informed consent. Participants will be asked to complete baseline questionnaires on sociodemographic and illness-related information, past SSE behaviors, and psychological functioning at the clinic. Alternatively participants can complete the questionnaires at home and return them to the research team by mail. The research assistant (RA) will access the participants’ medical charts in order to complete the medical information sheet. The second assessment will take place in conjunction with the delivery of the dermatological education at the clinic 3 to 6 months after T1, i.e., at time 2 (T2). Participants will complete questionnaires about distress, coping strategies, physician support and about SSE knowledge, attitude, and self-efficacy. In addition, participants who, at the time of data collection, report having a spouse (i.e., having a committed intimate relationship), will be asked to answer questions related to their partner’s impact on SSE practice. Furthermore, these patients will be asked to take home a survey for their spouse, which mirrors the partner-related questions that the patient is asked to answer regarding SSE. Also at time 2, all study participants will receive a 20-minute standardized dermatological education on SSE derived from empirical evidence [14, 29, 47, 50, 65, 98–104] and best practice guidelines [36, 38, 105–109]. Patients will be encouraged to attend the education session together with a significant other (e.g., spouse, other family member, friend) who could assist them with SSE. During the education session, the dermatology-trained RA, i.e., the health educator, will emphasize the usefulness of monthly whole body exams as an effective measure to detect suspicious skin lesions as early as possible. The educator will provide detailed information about how to conduct an effective SSE. This will include an explanation of the well-established ABCDE paradigm (lesion Asymmetry; Border irregularity; Color variation; Diameter; Evolution, e.g. change in size, shape, symptoms, etc.) [110–113] for the detection and interpretation of pigmented lesions by lay persons and health care professionals. Furthermore, the educator will provide handouts, which will assist participants with regular SSE, including a summarizing brochure on melanoma [114], a bookmark with color printed examples of lesions [111], a leaflet providing the link to an online video modeling skin self-examination [115], and a SSE Journal to record skin spots of concern and body parts covered during each home SSE [116, 117]. At the end of this 20-minute session, the educator will encourage the participant to reflect on their SSE intentions. Subsequently the participant will be asked to note down in the SSE journal if, when, where, and assisted by whom the participant plans to conduct self-exams. At time 3 (T3), i.e., 3 months after the dermatological education, participants are invited by letter to fill out questionnaires assessing distress, coping strategies, physician and spousal support as well as SSE knowledge, attitude, and self-efficacy. In addition, a 10-minute, structured SSE behavior interview with the RA will be scheduled for T3 to assess practice of SSE over the last 3 months. At time 4 (T4), 12 months after the dermatological education, participants will be invited by letter to complete an assessment identical to T3, i.e., questionnaires and SSE behavior interview. At T4 a subsample of 30 patients, which will include the first 15 men and the first 15 women who consent to participate, will be invited to take part in a 50-minute individual, semi-structured interview based on the McGill Illness Narrative Interview [118] focusing on the following questions: 1) how patients deal with the diagnosis and how they experience the illness; 2) their experience regarding SSE, including how they deal with the ongoing need for thorough SSEs and obstacles to SSE; 3) their experience of physician support of SSE, or lack thereof, and how they deal with it; and 4) their experience of partner support of SSE, or lack thereof, and what facilitates or hinders partner support and how they deal with it. Biological sex is considered explicitly given that previous melanoma research suggests that this is a key variable in relation to SSE [27, 45, 119–121]. Participants will be invited to share and report their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in each of the 4 domains, which were selected based on their relevance to the cancer trajectory and their presumed significance for SSE practice.

Measures

Descriptive and independent variables: predictors of skin self-examination

Study measures were selected based on their wide use in cancer research, on their psychometric properties, and on their direct relevance to the objectives of the project. They are used to assess descriptive and independent variables, which are expected to have an effect on SSE behaviors during the first 3 months (T1) and 12 months (T2) after dermatological education.

The Sociodemographic Information Form [67] includes questions about age, sex, education, having a spouse, socioeconomic status, and cancer diagnosis. With the Medical Information Sheet [30] the RA gathers data such as time since diagnosis, melanoma stage and depth, previous diagnosis of cancer, melanoma treatment and disease progression. The Skin Cancer Prevention Scale [122] captures whether patients performed SSE and have been advised by health care providers about SSE prior to their current melanoma diagnosis. The Skin Cancer Knowledge Scale, based on questionnaires by Hay et al. 2006 [65] and Manne et al. 2006 [45], assesses knowledge regarding melanoma risk, melanoma warning signs and SSE. The SSE Attitude Scale, an adaptation of Manne’s SSE Benefits and Barriers Scale [45], assesses perceptions of SSE importance, personal gain through SSE, and barriers to SSE. The SSE Self-Efficacy Scale, based on Weinstock et al. 2007 [123], captures an individual’s self-confidence in performing effective skin self-exams. The Physician SSE Support Scale [124] inquires about the perceived interest that the treating physician conveys regarding the patient’s practice of SSE. The Berlin Social Support Scale [125] assesses the patient’s perception of emotional, instrumental and informational illness support provided by their spouse (patient perception and partner perception). The Skin Cancer Index [126, 127] is a self-report scale focusing on emotional, social and appearance-related concerns associated with skin cancer. The Patient Health Questionnaire, PHQ-4, [128] screens for symptoms of depression and anxiety. The COPE Inventory [129] inquires about an individual’s use of coping strategies, e.g., mental disengagement, behavioral disengagement, focus on and venting of emotions, use of instrumental social support, denial, humor, use of emotional social support, planning and others.

Dependent variables: skin self-examination

Adherence to medical advice on SSE is assessed at 3 months (T3) and at 12 months (T4) after the standardized education session. Based on prior SSE research [30, 45, 58] and on recommendations for a monthly, comprehensive skin self-exam from the Canadian Dermatology Association [130], the American Academy of Dermatology [108] and the American Cancer Society [38], a structured SSE-behavior interview was developed and pilot tested [30]. During this 10-minute interview the RA records SSE behaviors in terms of SSE completeness and frequency. With the help of a calendar and the body map, which participants receive during the education session in order to document each SSE at home, SSE is recorded for five specified areas of the body: 1) head and neck; 2) front upper body including arms and shoulders; 3) front lower body including groin/genital area, legs, and feet; 4) back upper body including lower back; 5) back lower body including buttocks and back of legs. SSE assistance by significant others and the use of melanoma pictures during the self-exams will be documented. The first dependent variable, Completeness of SSE, refers to the examination of the 5 body areas mentioned above. The RA inquires about each of these 5 parts of the body for each skin self-exam reported by the patient over the last three months at T3 and at T4. The interviewer gives one point for each body area examined, for a possible total of 5 points reflecting the completeness, in regards to the 5 body areas, of each SSE conducted. A mean score (on 5) is calculated across all SSEs. The second dependent variable is Frequency of SSE over a given time period. Over the period of 3 months covered by the assessment at T3 and at T4, ideal frequency would be 3 SSEs, with more than 3 SSEs reflecting too high a frequency, and less than 3 reflecting too low a frequency. The total count of SSEs (i.e., how many times a patient performed a SSE) over 3 months will be used to determine if the frequency with which an individual patient conducted SSEs was too low, ideal or too high, which will be used for the data analysis.

Data analysis

In all relevant cases, additional analyses, including interaction effects and subsample differences, will be examined. Data analyses related to objective 1 ( i.e., determining the extent of thorough SSE performance defined in terms of frequency and completeness): Descriptive and inferential statistics will be employed to gain a differential picture of patients’ practice of SSE in terms of completeness and frequency at T3 and T4 for the total sample as well as for subsamples according to sex, age, having a partner, etc. Data analyses related to objective 2 (i.e., identifying psychosocial variables independently associated with thorough SSE): First, hierarchical multiple regressions will be performed with SSE completeness as dependent variable using T3 data, i.e., 3 months after standardized dermatological education. The independent variables described above will be entered block-wise, i.e., 1st block: sex; 2nd: skin cancer knowledge, attitude toward SEE; 3rd: self-efficacy for performing SSE; 4th: skin cancer-specific distress measure; 5th: partner support and physician support; 6th: total score of the coping measure (note that analyses will be repeated with the individual coping subscales). Second, a multinomial regression will be conducted with the same predictor variables and SSE frequency (i.e., too low, ideal and too high frequency) as the dependent variable. The strategies described for T3 will be repeated using the data collected at T4, i.e., 12 months after the education session. With the projected sample size of N = 200, a minimal R2 increment of .08 will be detected with .79 power. The power for detecting a R2 increment of .09 will be .85. The variance explained by both blocks and individual variables will be examined. The two dependent variables are treated separately because they reflect different aspects of SSE practice. As a second step, they may also be clustered and the resulting composite measure of SSE behavior will serve as the dependent variable in regressions similar to the ones described above. Data analyses related to objective 3 ( using qualitative methods for an in-depth understanding of psychosocial factors related to SSE): Data saturation in qualitative theme analysis, depending on the level of structure of the interview, is often achieved with a sample of 10–15 participants who are examined intensively, while larger samples typically add only minimal new data [131]. Consensual Qualitative Research [131–133] will be applied to the semi-structured interviews of 15 male and 15 female patients. This qualitative method is based on principles of grounded theory [134] and aims at developing a theory directly grounded in the phenomena under study. As a first step, the 2 independent sets of interviews will be theme analyzed to establish preliminary categorizations through open coding. To guide this, the following preliminary questions will be used: how do patients cognitively, affectively and behaviorally adjust to cancer diagnosis and treatment?; how and why do patients engage in or refrain from performing SSE?; how do they experience practicing SSE (e.g., does SSE evoke discomfort, does it trigger tumor fear, does it lead to a sense of safety and control?); in which ways do significant others support or undermine SSE practice?; do patients find it hard to ask significant others for help with SSE or do patients feel overwhelmed by a others’ motivation to help?; and in which ways are physicians experienced as helpful or as non-supportive? Axial coding will then be conducted by which open codes are reviewed and synthesized. As a final step, selective coding will be conducted in order to articulate theories derived from the data and establish the inter-relations between the constructs that were found. By definition, Consensual Qualitative Research is conducted independently by two raters, who then meet to discuss their coding until a consensus is reached. A third independent rater will be available to address disagreements. All proposals are then edited by an editor.

Discussion

Given the lack of therapeutic options for melanoma, the importance of SSE for the early detection of melanoma, and the limited body of knowledge regarding psychosocial predictors of SSE, this project is expected to generate greatly needed information regarding short- and long-term facilitators and barriers to SSE. By explaining which psychosocial factors affect acquisition and maintenance of SSE, the findings will help to tailor health services and prevention strategies as well as guide professional psychosocial support in order to overcome psychological challenges for sustained SSE practice. The derived knowledge, including information about effective self-management strategies, will not only be disseminated via scientific journals but also amongst health service providers, e.g., within the North-American Cancer Patient Education Network (CPEN), which unites health care professionals to promote models of excellence in patient, family, and community education across the continuum of care. Moreover, the findings are expected to also affect high-risk individuals not previously diagnosed with melanoma by informing secondary prevention efforts for populations such as individuals with non-melanoma skin cancer, with dysplastic nevi or with a family history of skin cancer. Lastly, this study is setting the basis for the design of a state-of-the-art psychosocial intervention program tailored to the SSE risk profile of an individual. The impact of such a psychological complement to standard dermatological education on optimal SSE practice can then be evaluated in an RCT.

Abbreviations

- SSE:

-

Skin self-examination

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- RA:

-

Research assistant

- T1:

-

Time 1

- T2:

-

Time 2

- T3:

-

Time 3

- T4:

-

Time 4

- FRSQ:

-

Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec

- CIHR:

-

Canadian Institutes of Health Research

- PORT:

-

Psychosocial Oncology Research Training.

References

Bleyer A, O’Leary M, Barr R, Ries LAG (Eds): NIH Pub. No. 06–5767 In Cancer Epidemiology in Older Adolescents and Young Adults 15 to 29 Years of Age, Including SEER Incidence and Survival: 1975–2000. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2006.

Ries LA, Wingo PA, Miller DS, Howe HL, Weir HK, Rosenberg HM: The annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1973–1997, with a special section on colorectal cancer. Cancer 2000, 88: 2398–2424. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(20000515)88:10<2398::AID-CNCR26>3.0.CO;2-I

Hausauer AK, Swetter SM, Cockburn MG, Clarke CA: Increases in melanoma among adolescent girls and young women in California: trends by socioeconomic status and UV radiation exposure. Arch Dermatol 2011,147(7):783–789. 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.44

de Vries E, Bray FI, Coebergh JW, Parkin DM: Changing epidemiology of malignant cutaneous melanoma in Europe 1953–1997: rising trends in incidence and mortality but recent stabilizations in western Europe and decreases in Scandinavia. Int J Cancer 2003, 107: 119–126. 10.1002/ijc.11360

Horner MJ, Ries LAG, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Howlader N, Altekruse SF, Feuer EJ, Huang L, Mariotto A: SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2006. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2009.

Safarians S, Sternlight MD, Freiman CJ, Huaman JA, Barsky SH: The primary tumor is the primary source of metastasis in a human melanoma/SCID model. Implications for the direct autocrine and paracrine epigenetic regulation of the metastatic process. Int J Canc 1996,66(2):151–158. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960410)66:2<151::AID-IJC2>3.0.CO;2-1

Yang EV, Kim SJ, Donovan EL, Chen M, Gross AC, Webster Marketon JI, Barsky SH, Glaser R: Norepinephrine upregulates VEGF, IL-8, and IL-6 expression in human melanoma tumor cell lines: implications for stress-related enhancement of tumor progression. Brain Behav Immun 2009,23(2):267–275. 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.10.005

Balch CM, Buzaid AC, Soong SJ, Atkins MB, Cascinelli N, Coit DG: Final version of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system for cutaneous melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2001, 19: 3635–3648.

Berwick M, Erdei E, Hay J: Melanoma epidemiology and public health. Dermatol Clin 2009,27(2):205–214. 10.1016/j.det.2008.12.002

Markovic SN, Erickson LA, Rao RD, Weenig RH, Pockaj BA, Bardia A, Vachon CM, Schild SE, McWilliams RR, Hand JL: Malignant melanoma in the 21st century, part 1: Epidemiology, risk factors, screening, prevention, and diagnosis. Mayo Clin Proc 2007, 82: 364–380.

Rhodes AR: Cutaneous melanoma and intervention strategies to reduce tumor-related mortality: What we know, what we don't know, and what we think we know that isn't so. Dermatol Ther 2006, 19: 50–69. 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2005.00056.x

Geller AC, Swetter SM, Brooks K, Demierre MF, Yaroch AL: Screening, early detection, and trends for melanoma: Current status (2000–2006) and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007, 57: 555–572. 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.06.032

Burdern AD, Vestey JP, Srel M, Aitchison TC, Hunter JA, MacKie RM: Multiple primary melanoma: Risk factors and prognostic implications. Br Med J 1994, 309: 376.

Uliasz A, Lebwohl M: Patient education and regular surveillance results in earlier diagnosis of second primary melanoma. Int J Dermatol 2007, 46: 575–577. 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.02704.x

Ferrone CR, Ben Porat L, Panageas KS, Berwick M, Halpern AC, Patel A: Clinicopathological features of and risk factors for multiple primary melanomas. J Am Med Assoc 2005, 294: 1647–1654. 10.1001/jama.294.13.1647

Kang S, Barnhill RL, Mihm MC, Sober AJ: Multiple primary cutaneous melanomas. Cancer 1992,70(7):1911–1916. 10.1002/1097-0142(19921001)70:7<1911::AID-CNCR2820700718>3.0.CO;2-Q

Manganoni AM, Farisoglio C, Tucci G, Facchetti F, Calzavara Pinton PG: The importance of self-examination in the earliest diagnosis of multiple primary cutaneous melanomas: A report of 47 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2007, 21: 1333–1336. 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02263.x

Stam-Posthuma JJ, Van Duinen C, Scheffer E, Vink J, Bergman W: Multiple primary melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001, 44: 22–27. 10.1067/mjd.2001.110878

Garbe C, Paul A, Kohler-Spath H, Ellwanger U, Stroebel W, Schwarz M: Prospective evaluation of a follow-up schedule in cutaneous melanoma patients: Recommendations for an effective follow-up strategy. J Clin Oncol 2003, 21: 520–529. 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.091

Weinstock MA: Progress and prospects on melanoma: The way forward for early detection and reduced mortality. Clin Cancer Res 2006, 12: 2297–2300. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2559

Berwick M, Armstrong BK, Ben-Porat L, Fine J, Kricker A, Eberle C: Sun exposure and mortality from melanoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005, 97: 195–199. 10.1093/jnci/dji019

Cokkinides V, Weinstock M, Glanz K, Albano J, Ward E, Thun M: Trends in sunburns, sun protection practices, and attitudes toward sun exposure protection and tanning among US adolescents, 1998–2004. Pediatrics 2006, 118: 853–864. 10.1542/peds.2005-3109

Gandini S, Sera F, Cattaruzza MS, Pasquini P, Picconi O, Boyle P: Meta-analysis of risk factors for cutaneous melanoma: II. Sun exposure. Eur J Cancer 2005, 41: 45–60. 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.10.016

Kennedy C, Bajdik CD, Willemze R, De Gruijl FR, Bouwes Bavinck JN: The influence of painful sunburns and lifetime sun exposure on the risk of actinic keratoses, seborrheic warts, melanocytic nevi, atypical nevi, and skin cancer. J Invest Dermatol 2003, 120: 1087–1093. 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12246.x

Kasparian N, McLoone J, Meiser B: Skin cancer-related prevention and screening behaviors: a review of the literature. J Behav Med 2009,32(5):406–428. 10.1007/s10865-009-9219-2

Brady MS, Oliveria SA, Christos PJ, Berwick M, Coit DG, Katz J: Patterns of detection in patients with cutaneous melanoma. Cancer 2000, 89: 342–347. 10.1002/1097-0142(20000715)89:2<342::AID-CNCR19>3.0.CO;2-P

Carli P, De Giorgi V, Palli D, Maurichi A, Mulas P, Orlandi C: Dermatologist detection and skin self-examination are associated with thinner melanomas: Results from a survey of the Italian Multidisciplinary Group on Melanoma. Arch Dermatol 2003, 139: 607–612. 10.1001/archderm.139.5.607

Epstein DS, Lange JR, Gruber SB, Mofid M, Koch SE: Is physician detection associated with thinner melanomas? J Am Med Assoc 1999, 281: 640–643. 10.1001/jama.281.7.640

Schwartz JL, Wang TS, Hamilton TA, Lowe L, Sondak VK, Johnson TM: Thin primary melanomas: associated detection patterns, lesion characteristics, and patient characteristics. Cancer 2002, 95: 1562–1568. 10.1002/cncr.10880

Körner A, Coroiu A, Martins C, Wang B: Predictors of skin self-examination before and after a melanoma diagnosis: The role of medical advice and patient’s level of education. Int Arch Med 2013, 6: 8. 10.1186/1755-7682-6-8

Schneider JS, Moore DH 2nd, Mendelsohn ML: Screening program reduced melanoma mortality at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, 1984 to 1996. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008, 58: 741–749. 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.10.648

Aitken JF, Janda M, Elwood M, Youl PH, Ring IT, Lowe JB: Clinical outcomes from skin screening clinics within a community-based melanoma screening program. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006, 54: 105–114. 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.08.072

Aitken JF, Youl PH, Janda M, Lowe JB, Ring IT, Elwood M: Increase in skin cancer screening during a community-based randomized intervention trial. Int J Cancer 2006, 118: 1010–1016. 10.1002/ijc.21455

Berwick M, Begg CB, Fine JA, Roush GC, Barnhill RL: Screening for cutaneous melanoma by skin self-examination. J Natl Cancer Inst 1996, 88: 17–23. 10.1093/jnci/88.1.17

Dalal KM, Zhou Q, Panageas KS, Brady MS, Jaques DP, Coit DG: Methods of detection of first recurrence in patients with stage I/II primary cutaneous melanoma after sentinel lymph node biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol 2008, 15: 2206–2214. 10.1245/s10434-008-9985-z

Coit DG, Andtbacka R, Anker CJ, Bichakjian CK, Carson WE, Daud A, Dilawari RA, DiMaio D, Guild V, Halpern AC: NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®): Melanoma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2012,10(3):366–400.

National Cancer Institute: What You Need To Know About™ Melanoma and Other Skin Cancers. Rockville, MD; 2010.

American Cancer Society: Skin Cancer - Melanoma: Early Detection, Diagnosis, and Staging. [http://www.cancer.org/cancer/skincancer-melanoma/overviewguide/melanoma-skin-cancer-overview-diagnosed]

American Academy of Dermatology: Skin Exams Save Lifes: Body Mole Map. [http://www.aad.org/spot-skin-cancer/understanding-skin-cancer/how-do-i-check-my-skin]

Robinson JK, Fisher SG, Turrisi RJ: Predictors of skin self-examination performance. Cancer 2002, 95: 135–146. 10.1002/cncr.10637

Geller AC, O'Riordan DL, Oliveria SA, Valvo S, Teich M, Halpern AC: Overcoming Obstacles to Skin Cancer Examinations and Prevention Counseling for High-Risk Patients: Results of a National Survey of Primary Care Physicians. J Am Board Fam Pract 2004,17(6):416–423. 10.3122/jabfm.17.6.416

Robinson JK, Mallett KA, Turrisi R, Stapleton J, Robinson JK, Mallett KA, Turrisi R, Stapleton J: Engaging Patients and their Partners in Preventive Health Behaviors: The Physician Factor. Arch Dermatol 2009,145(4):469–473. 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.2

Koh HK, Miller DR, Geller AC, Clapp RW, Mercer MB, Lew RA: Who discovers melanoma? Patterns from a population-based survey. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992,26(6):914–919. 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70132-Y

Terushkin V, Halpern AC: Melanoma early detection. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2009,23(3):481–500. 10.1016/j.hoc.2009.03.001

Manne S, Lessin S: Prevalence and correlates of sun protection and skin self-examination practices among cutaneous malignant melanoma survivors. J Behav Med 2006, 29: 419–434. 10.1007/s10865-006-9064-5

Mujumdar UJ, Hay JL, Monroe-Hinds YC, Hummer AJ, Begg CB, Wilcox HB, Oliveria SA, Berwick M: Sun protection and skin self-examination in melanoma survivors. Psychooncology 2009,18(10):1106–1115. 10.1002/pon.1510

DiFronzo LA, Wanek LA, Morton DL: Earlier diagnosis of second primary melanoma confirms the benefits of patient education and routine postoperative follow-up. Cancer 2001, 91: 1520–1524. 10.1002/1097-0142(20010415)91:8<1520::AID-CNCR1160>3.0.CO;2-6

Friedman RJ, Rigel DS, Silverman MK, Kopf AW, Vossaert KA: Malignant melanoma in the 1990s: The continued importance of early detection and the role of physician examination and self-examination of the skin. Canc J Clin 1991,41(4):201–226. 10.3322/canjclin.41.4.201

Azzarello LM, Dessureault S, Jacobsen PB: Sun-protective behavior among individuals with a family history of melanoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006,15(1):142–145. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0478

Robinson JK, Turrisi R, Stapleton J: Efficacy of a partner assistance intervention designed to increase skin self-examination performance. Arch Dermatol 2007, 143: 37–41. 10.1001/archderm.143.1.37

Robinson JK, Stapleton J, Turrisi R: Relationship and partner moderator variables increase self-efficacy of performing skin self-examination. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008, 58: 755–762. 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.12.027

Robinson JK, Turrisi R, Stapleton J: Examination of mediating variables in a partner assistance intervention designed to increase performance of skin self-examination. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007, 56: 391–397. 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.10.028

Körner A, Augustin M, Zschocke I: Health behaviors of skin cancer patients in melanoma follow-up care. Z Gesundh 2011,19(1):2–12. 10.1026/0943-8149/a000035

Chiu V, Won E, Malik M, Weinstock MA: The use of mole-mapping diagrams to increase skin self-examination accuracy. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006,55(2):245–250. 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.02.026

Robinson JK, Rigel DS, Amonette RA: What promotes skin self-examination? J Am Acad Dermatol 1998, 38: 752–757. 10.1016/S0190-9622(98)70204-X

Berwick M, Oliveria S, Luo ST, Headley A, Bolognia JL: A pilot study using nurse education as an intervention to increase skin self-examination for melanoma. J Cancer Educ 2000, 15: 38–40.

Oliveria SA, Dusza SW, Phelan DL, Ostroff JS, Berwick M, Halpern AC: Patient adherence to skin self-examination effect on nurse intervention with photographs. Am J Prev Med 2004, 26: 152–155. 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.10.006

Weinstock MA, Risica PM, Martin RA, Rakowski W, Smith KJ, Berwick M: Reliability of assessment and circumstances of performance of thorough skin self-examination for the early detection of melanoma in the Check-It-Out Project. Prev Med 2004, 38: 761–765. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.01.020

Hamidi R, Peng D, Cockburn M: Efficacy of skin self-examination for the early detection of melanoma. Int J Dermatol 2010,49(2):126–134. 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04268.x

Kasparian NA, Branstrom R, Chang YM, Affleck P, Aspinwall LG, Tibben A, Azizi E, Baron-Epel O, Battistuzzi L, Bruno W: Skin examination behavior: The role of melanoma history, skin type, psychosocial factors, and region of residence in determining clinical and self-conducted skin examination. Arch Dermatol 2012,148(10):1–10.

McPherson M, Elwood M, English DR, Baade PD, Youl PH, Aitken JF: Presentation and detection of invasive melanoma in a high-risk population. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006,54(5):783–792. 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.08.065

DiMatteo MR, Giordani PJ, Lepper HS, Croghan TW: Patient adherence and medical treatment outcomes: A meta-analysis. Med Care 2002,40(9):794–811. 10.1097/00005650-200209000-00009

DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW: Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: Meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med 2000, 160: 2101–2107. 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101

Hay JL, Buckley TR, Ostroff JS: The role of cancer worry in cancer screening: A theoretical and empirical review of the literature. Psychooncology 2005,14(7):517–534. 10.1002/pon.864

Hay JL, Oliveria SA, Dusza SW, Phelan DL, Ostroff JS, Halpern AC: Psychosocial mediators of a nurse intervention to increase skin self-examination in patients at high risk for melanoma. Canc Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006, 15: 1212–1216. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0822

Zschocke I, Rhein J, Grimme H, Stein B, Muthny FA, Augustin M: Self-examination of patients with malignant melanoma in the aftercare: Relevance of psychosocial factors and instructions by the physicians. Dermatol Psychosom 2000, 1: 8–14. 10.1159/000057992

Roberts N, Czajkowska Z, Radiotis G, Körner A: Distress and coping strategies among patients with skin cancer. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2012, . 10.1007/s10880-012-9319-y

Hamama-Raz Y, Solomon Z, Schachter J, Azizi E: Objective and subjective stressors and the psychological adjustment of melanoma survivors. Psychooncology 2007, 16: 287–294. 10.1002/pon.1055

Sollner W, Zschocke I, Zingg-Schir M, Stein B, Rumpold G, Fritsch P, Augustin M: Interactive patterns of social support and individual coping strategies in melanoma patients and their correlations with adjustment to illness. Psychosomatics 1999,40(3):239–250. 10.1016/S0033-3182(99)71241-7

Temoshok L: Malignant melanoma, AIDS, and the complex search for psychosocial mechanisms. Advances 1991, 7: 20–28.

Kneier AW: The psychological challenges facing melanoma patients. Surg Clin North Am 1996,76(6):1413–1421. 10.1016/S0039-6109(05)70523-5

Kneier AW, Temoshok L: Repressive coping reactions in patients with malignant melanoma as compared to cardiovascular disease patients. J Psychosom Res 1984,28(2):145–155. 10.1016/0022-3999(84)90008-4

Lichtenthal W, Cruess DG, Schuchter LM, Ming ME: Psychosocial factors related to the correspondence of recipient and provider perceptions of social support among patients diagnosed with or at risk for malignant melanoma. J Health Psychol 2003,8(6):705–719. 10.1177/13591053030086005

Dirksen S: Perceived well-being in malignant melanoma survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum 1989,16(3):353–358.

Kasparian NA, McLoone JK, Butow PN: Psychological responses and coping strategies among patients with malignant melanoma: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Dermatol 2009,145(12):1415–1427. 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.308

Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK: Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. 4th edition. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008.

Cancer Registry - McGill University Health Centre: Prevalence of cutaneous melanoma at the McGill University Health Centre in 2000–2007. Montreal, QC: McGill University Health Centre; 2009.

Prevalence of cutaneous melanoma at the Jewish General Hospital in 2005–2007: Title. Thesis Type. Jewish General Hospital: University; 2008.

Khanna M, Fortier-Riberdy G, Smoller B, Dinehart SM: Reporting tumor thickness for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol 2002, 29: 321–323. 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2002.290601.x

Lebel S, Jakubovits G, Rosberger Z, Loiselle C, Seguin C, Cornaz C, Ingram J, August L, Lisbona A: Waiting for a breast biopsy. Psychosocial consequences and coping strategies. J Psychosom Res 2003,55(5):437–443. 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00512-9

Couper JWBS, Love A, Duchesne G, Macvean M, Kissane DW: The psychosocial impact of prostate cancer on patients and their partners. Med J Aust 2006,185(8):428–432.

Hersch J, Juraskova I, Price M, Mullan B: Psychosocial interventions and quality of life in gynaecological cancer patients: A systematic review. Psychooncology 2009, 18: 795–810. 10.1002/pon.1443

Dale HLAP, Humphris GM: Systematic review of post-treatment psychosocial and behaviour change interventions for men with cancer. Psychooncology 2010, 19: 227–237. 10.1002/pon.1598

Schou I, Ekeberg O, Karesen R, Sorensen E: Psychosocial intervention as a component of routine breast cancer care—who participates and does it help? Psychooncology 2008,17(7):716–720. 10.1002/pon.1264

Lebel S, Rosberger Z, Edgar L, Devins GM: Predicting stress-related problems in long-term breast cancer survivors. J Psychosom Res 2008, 65: 513–523. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.07.018

Moadel AB, Shah C, Wylie-Rosett J, Harris MS, Patel SR, Hall CB, Sparano JA: Randomized Controlled Trial of Yoga Among a Multiethnic Sample of Breast Cancer Patients: Effects on Quality of Life. J Clin Oncol 2007,25(28):4387–4395. 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.6027

Antoni MH, Wimberly SR, Lechner SC, Kazi A, Sifre T, Urcuyo KR, Phillips K, Smith RG, Petronis VM, Guellati S: Reduction of Cancer-Specific Thought Intrusions and Anxiety Symptoms With a Stress Management Intervention Among Women Undergoing Treatment for Breast Cancer. Am J Psychiatry 2006,163(10):1791–1797. 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.10.1791

McCorkle R, Dowd M, Ercolano E, Schulman-Green D, Williams A, Siefert ML, Steiner J, Schwartz P: Effects of a nursing intervention on quality of life outcomes in post-surgical women with gynecological cancers. Psychooncology 2009,18(1):62–70. 10.1002/pon.1365

Manne SL, Rubin S, Edelson M, Rosenblum N, Bergman C, Hernandez E, Carlson J, Rocereto T, Winkel G: Coping and Communication-Enhancing Intervention Versus Supportive Counseling for Women Diagnosed With Gynecological Cancers. J Consult Clin Psychol 2007,75(4):615–628.

Velji K: Effect of an individualized symptom education program on the symptom distress of women receiving radiation therapy for gynecological cancers. Toronto: University of Toronto; 2006.

Nolte S, Donnelly J, Kelly S, Conley P, Cobb R: A randomized clinical trial of a videotape intervention for women with chemotherapy-induced alopecia: a gynecologic oncology group study. Oncol Nurs Forum 2006,33(2):305–311. 10.1188/06.ONF.305-311

Chan YM, Lee PWH, Fong DYT, Fung ASM, Wu LYF, Choi AYY, Ng TY, Ngan HYS, Wong LC: Effect of Individual Psychological Intervention in Chinese Women With Gynecologic Malignancy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol 2005,23(22):4913–4924. 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.069

Geller AC, Emmons KM, Brooks DR, Powers C, Zhang Z, Koh HK, Heeren T, Sober AJ, Li F, Gilchrest BA: A randomized trial to improve early detection and prevention practices among siblings of melanoma patients. Cancer 2006,107(4):806–814. 10.1002/cncr.22050

Andersen BL: Biobehavioral outcomes following psychological interventions for cancer patients. J Consult Clin Psychol 2002,70(3):590–610.

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination CRD Report 30. In The effects of psychosocial interventions in cancer and heart disease: a review of systematic reviews. York: University of York; 2005.

Lostumbo L, Carbine N, Wallace J, Ezzo J: Prophylactic mastectomy for the prevention of breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010, CD002748.

Nezu AM, Nezu CM, Felgoise SH, McClure KS, Houts PS, Nezu AM, Nezu CM, Felgoise SH, McClure KS, Houts PS: Project Genesis: assessing the efficacy of problem-solving therapy for distressed adult cancer patients. J Consult Clin Psychol 2003,71(6):1036–1048.

Boone SL, Stapleton J, Turrisi R, Ortiz S, Robinson JK, Mallett KA, Boone SL, Stapleton J, Turrisi R, Ortiz S: Thoroughness of skin examination by melanoma patients: influence of age, sex and partner. Australas J Dermatol 2009,50(3):176–180. 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2009.00533.x

Blum A, Brand CU, Ellwanger U, Schlagenhauff W, Stroebel W, Rassner G: Awareness and early detection of cutaneous melanoma: An analysis of factors related to delay in treatment. Br J Dermatol 1999, 141: 783–787. 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.03196.x

Francken A, Thompson JF, Bastiaannet E, Hoekstra HJ: Detection of the first recurrence in patients with melanoma: three quarters by the patient, one quarter during outpatient follow-up. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2008, 152: 557–562.

Carli P, DeGiorgi V, Chiarugi A, Stante M, Giannotti B: Multiple synchronous cutaneous melanomas: implications for prevention. Int J Dermatol 2002,41(9):583–585. 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01605.x

Goggins WB, Tsao H: A population-based analysis of risk factors for a second primary cutaneous melanoma among melanoma survivors. Cancer 2003, 97: 639–643. 10.1002/cncr.11116

Walter FM, Humphrys E, Tso S, Johnson M, Cohn S: Patient understanding of moles and skin cancer, and factors influencing presentation in primary care: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract 2010,11(62):1471–2296.

Francken AB, Shaw HM, Accortt NA, Soong SJ, Hoekstra HJ, Thompson JF: Detection of first relapse in cutaneous melanoma patients: implications for the formulation of evidence-based follow-up guidelines. Ann Surg Oncol 2007, 14: 1924–1933. 10.1245/s10434-007-9347-2

Melanoma Network of Canada: About melanoma: Detection & Prevention.

Murchie P, Hannaford PC, Wyke S, Nicolson MC, Campbell NC: Designing an integrated follow-up programme for people treated for cutaneous malignant melanoma: A practical application of the MRC framework for the design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. Fam Pract 2007, 24: 283–292. 10.1093/fampra/cmm006

Garbe C, Hauschild A, Volkenandt M, Schadendorf D, Stolz W, Reinhold U: Evidence and interdisciplinary consensus-based German guidelines: Diagnosis and surveillance of melanoma. Melanoma Res 2007,17(6):393–399. 10.1097/CMR.0b013e3282f05039

American Academy of Dermatology: Guidelines for Performing a Skin Self-Exam. [http://www.aad.org/spot-skin-cancer/understanding-skin-cancer/how-do-i-check-my-skin]

National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Program: Diagnosis and Treatment of Early Melanoma. NIH Consens Statement Online 1992 Jan 27–29;10(1):1–26. [http://consensus.nih.gov/1992/1992Melanoma088html.htm]

Abbasi NR, Shaw HM, Rigel DS, Friedman RJ, McCarthy WH, Osman I, Kopf AW, Polsky D: Early diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma: Revisiting the ABCD criteria. J Am Med Assoc 2004, 292: 2771–2776. 10.1001/jama.292.22.2771

Canadian Dermatology Association: The ABCDEs of Malignant Melanoma. 2008.

Rigel DS, Russak J, Friedman R: The Evolution of Melanoma Diagnosis: 25 Years Beyond the ABCDs. Canc J Clin 2010,60(5):301–316. 10.3322/caac.20074

Rigel DS, Friedman RJ, Kopf AW, Polsky D: ABCDE - an evolving concept in the early detection of melanoma. Arch Dermatol 2005, 141: 1032–1034. 10.1001/archderm.141.8.1032

Canadian Dermatology Association: Brochure - Malignant Melanoma. Public education material. Ottawa, ON; 2008.

La Roche-Posay Laboratoire Dermatologique: Before showing it to the sun, show it to a dermatologist. Patient Education Material. Montreal, QC; 2012.

Körner A: Skin Self-Examination Journal. Unpublished patient education material. QC, Montreal: McGill University, Department of Educational and Counselling Psychology; 2011.

Moumne S, Czajkowska Z, Wang B, Khanna M, Körner A: The body map diary: Research tool and means for secondary prevention of melanoma. In Poster presented at the Annual conference of the Canadian Association of Psychosocial Oncology (CAPO): May 2011; Toronto, Canada. : ; 2011.

Groleau D, Young A, Kirmayer LJ: The McGill Illness Narrative Interview (MINI): an interview schedule to elicits meanings and modes of reasoning related to illness experience. Transcult Psychiatry 2006,43(4):671–691. 10.1177/1363461506070796

Miller DR, Geller AC, Wyatt SW, Halpern A, Howell JB, Cockerell C, Reilley BA, Bewerse BA, Rigel D, Rosenthal L, Amonette R, Sun T, Grossbart T, Lew RA, Koh HK: Melanoma awareness and self-examination practices: results of a United States survey. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996,34(6):962–970. 10.1016/S0190-9622(96)90273-X

Geller AC: Educational and screening campaigns to reduce deaths from melanoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2009,23(3):515–527. 10.1016/j.hoc.2009.03.008

Swetter S, Johnson T, Miller D, Layton C, Brooks K, Geller A: Melanoma in middle-aged and older men: a multi-institutional survey study of factors related to tumor thickness. Arch Dermatol 2009,145(4):397–404. 10.1001/archdermatol.2008.603

Körner A Ethics application for pilot study no. 10–126-PSY. In Adherence to medical advice - Understanding barriers and facilitators of skin self- examination in patients with melanoma. Montreal, QC: McGill University Health Centre; 2010.

Weinstock MA, Risica PM, Martin RA, Rakowski W, Dube C, Berwick M: Melanoma early detection with thorough skin self-examination: The "Check It Out" randomized trial. Am J Prev Med 2007, 32: 517–524. 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.024

Körner A Research protocol no. A00-B39–11B approved by the Institutional Review Board. In Reducing Melanoma-Related Mortality in High Risk Individuals: Barriers and Facilitators of Adherence to Skin Self-Examination. Montreal, QC: Faculty of Medicine, McGill University; 2011.

Schulz U, Schwarzer R: Long-term effects of spousal support on coping with cancer after surgery. J Soc Clin Psychol 2004,23(5):716–732. 10.1521/jscp.23.5.716.50746

Matthews BA, Rhee JS, Neuburg M, Burzynski ML, Nattinger AB: Development of the facial skin care index: a health-related outcome index for skin cancer patients. Dermatol Surg 2006,32(7):924–934. 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32197.x

Rhee J, Matthews B, Neuburg M, Logan B, Burzynski M, Nattinger A: The skin cancer index: clinical responsiveness and predictors of quality of life. Laryngoscope 2007,117(3):399–405. 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31802e2d88

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Lowe B: The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: A systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2010,32(4):345–359. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006

Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK: Assessing Coping Strategies - a Theoretically Based Approach. J Pers Soc Psychol 1989,56(2):267–283.

Canadian Dermatology Association: A Guide to Skin Cancer Self-Examination. Ottawa, ON; 2008.

Hill CE, Thompson BJ, Williams EN: A guide to conducting consensual qualitative research. Counsel Psychol 1997,25(4):517–572. 10.1177/0011000097254001

Hill C, Knox S, Thompson B, Nutt EW, Hess SA: Consensual qualitative research: An update. Counsel Psychol 2005, 52: 162–205.

Paulus T, Woodside M, Ziegler M: Extending the conversation: Qualitative research as dialogic collaborative process. Qual Rep 2008, 13: 226–243.

Strauss A, Corbin J: Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-5945/13/3/prepub

Acknowledgements

We thank our patients for their trust and Claudia Martins, MD, MSc, for her invaluable support of the patient education sessions. We extend our thanks to our dedicated clinical care and research teams for their contribution to the successful implementation of this study protocol.

Funding statement

This study is funded by operating grants from the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec (FRQS) and the Ride to Conquer Cancer (RTCC) research fund. Furthermore the study is supported through student training awards: Ms. DiMillo’s work is supported by a FRSQ doctoral training award; Ms. Czajkowska is supported by doctoral training awards from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and from the Psychosocial Oncology Research Training (PORT) program; Ms. Coroiu’s work is supported by Master’s training awards from CIHR, FRSQ and PORT. Dr. Drapeau was supported by a Career Award from the FRSQ. Dr. Thombs was supported by a New Investigator Award from the CIHR. The funding is non-commercial. While all funding applications underwent full peer-review, none of the funding bodies influences study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit this manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or non-financial competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AK conceptualized the study, designed the research protocol, directly oversees the implementation of the study, drafted the research proposal submitted to the funding agency, and wrote the current manuscript. MD contributed substantially to the initial design of the research methodology and performed the power calculations. BT reviewed the initial study design and critically revised the current manuscript for important intellectual content. MD, GB, ZR, and AS contributed to the development of the study protocol, to its implementation at the participating clinical sites and to revisions of the current manuscript. BW and MK supervise the determination of patient eligibility to join the study as well as the delivery of the study intervention. Both provided feedback on the study protocol, on the design of the study intervention and on final revisions of the current manuscript. BW provides the training of the health educator. AC participated in the review and selection of the study measures, designed the study database, oversees data entry, and edited several drafts of this manuscript. RG coordinates the study, contributed to the design and implementation of the study intervention, and provided feedback on this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Körner, A., Drapeau, M., Thombs, B.D. et al. Barriers and facilitators of adherence to medical advice on skin self-examination during melanoma follow-up care. BMC Dermatol 13, 3 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-5945-13-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-5945-13-3