Abstract

Background

There is growing evidence that male circumcision (MC) prevents heterosexual acquisition of HIV by males in sub-Saharan Africa, the region of the world heavily affected by the HIV pandemic. While there is growing support for wide-spread availability and accessibility of MC in Africa, there is limited discussion about the prevalence of physical complications of male circumcision on the continent.

Methods

A systematic literature search and review of articles in indexed journals and conference abstracts was conducted to collect and analyze prevalence of complications of MC in Anglophone sub-Saharan Africa. Information extracted included: indications for MC, complications reported, age of patients and category of circumcisers.

Results

There were 8 articles and 2 abstracts that were suitable for the analysis. The studies were not strictly comparable as some reported on a wide range of complications while others reported just a limited list of possible complications. Prevalence of reported complications of MC ranged from 0% to 50.1%. Excluding the study with 50.1%, which was on a series of haemophilia patients, the next highest prevalence of complications was 24.1%. Most of the complications were minor. There was no firm evidence to suggest that MCs performed by physician surgeons were associated with lower prevalence of complications when compared with non-physician health professionals.

Conclusion

The available data are inadequate to obtain a reasonable assessment of the prevalence of complications of MC in sub-Saharan Africa. Some of the available studies however report potentially significant prevalence of complications, though of minor clinical significance. This should be considered as public health policy makers consider whether to scale-up MC as an HIV preventative measure. Decision for the scale-up will depend on a careful cost-benefit assessment of which physical complications are certainly an important aspect. There is need for standardized reporting of complications of male circumcision.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The HIV pandemic is among the most critical public health challenges facing the African continent. Observational studies and three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have reported that male circumcision can prevent HIV acquisition heterosexually by men [1–3]. Williams et al [4] have conducted mathematical models showing that wide-scale implementation of MC has the potential of reducing 2.0 million (1.1–3.8 million) new HIV infections in the first ten years of implementation in sub-Saharan Africa.

Several studies have reported on the acceptability of male circumcision for the prevention of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa [5–7]. In a review, Westercamp and Bailey report that there is sufficient research evidence to suggest that male circumcision is acceptable in sub-Saharan Africa for the prevention of HIV transmission [8]. However, Mills and Siegfried have suggested a "cautious optimism" approach towards male circumcision [9]. There is on-going debate as to whether male circumcision should be routinely performed for the purpose of preventing heterosexual transmission of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa [10–15].

While the literature has focused on the role of MC in the prevention of transmission of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa, we argue that there has not been commensurate interest in the estimation of safety and complications potentially associated with any scale-up in MC in Africa. In conducting this review, we were motivated to find out the available evidence regarding the reported prevalence of complications of MC in Africa. We therefore conducted a review of the published literature to attempt to answer the question: What has been the reported prevalence of complications of MC in sub-Saharan Africa? A secondary question is: Who is conducting MC in Africa?

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

We searched for all reports in peer-reviewed journals that reported on complications of male circumcision in sub-Saharan Africa and abstracts from the International Conference on AIDS (2004 and 2006). Journal databases searched included: African Journals Online (AJOL), MEDLINE, OVID, Google Scholar and Web of Science. The search period was limited to 1980 and August 2006. We used the key word: "circumcision". Studies were included for analysis if they reported on any series of patients in Anglophone Africa on whom male circumcision had been conducted and complications reported. ASM, RM and JII participated in the data collection. Data abstracted included: author details, location of study, number of patients circumcised in the reported series, ages of patients, inclusion criteria for procedure, prevalence of complications, nature of complications reported, period of follow-up for reporting of complications, indications for circumcision and who performed the circumcisions. Only studies published in English were included, irrespective of study design. Our method used applicable recommendations from the Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines as reported by Stroup et al [16].

Results

Clinical characteristics of cases

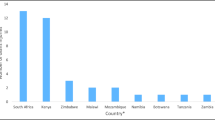

Eight articles and two conference abstracts were considered suitable for the review. The papers reported on studies conducted in Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa and Tanzania. Table 1 reports on indications reported for MC, exclusion criteria of cases, length of period of follow-up and the range of complications reported, which included zero reporting. Zero reporting means type of complication was reported as having never occurred.

Studies included randomized controlled clinical trials and reports of routine clinical work. The inclusion and exclusion criteria in the series of cases were diverse with the RCTs reporting stringent inclusion criteria of cases while the routine series of patients were generally less restrictive. The lists of complications reported in studies were different. The period of follow-up to document complications were variable ranging from just immediate post-operative up to a year. 4 of the 10 studies did not report follow-up time.

Complications of male circumcision

Table 2 reports on the total number of cases in a series group, age of patients, categories of circumciser and prevalence of complications reported. The prevalence of complication reported ranged from 0% to 50.1% in a series of hemophiliacs. Different professional categories performed circumcision. There were equivocal reports on the comparison of complications between circumcisions performed by nurses versus those performed by physicians.

Association between category of circumciser and complications

Several studies reported high prevalence of complications when circumcision was conducted by untrained personnel. Osuigwe et al [23] reported that midwives were associated with 30.6% complications compared to physicians at 14.5%. However, physicians at a university teaching hospital were associated with fewer complications compared to private and mission hospital physicians. The series of cases by Magoha [26] and Manji [25] were operated on by one physician in each case and no comparisons could be made about the skill of the circumciser. Auvert et al study [20] used general physicians for all their subjects. Okeke et al [19] reported more complications with nurses compared to physicians. However, the difference was not statistically significant.

Discussion

There is limited published literature on the complications of male circumcision in sub-Saharan Africa. The available evidence regarding the prevalence of complications in male circumcision is conflicting, with some studies reporting significantly high complications prevalence and at least one study reporting no complications. It is plausible to consider that a study that may not have reported a single complication may indeed have none to report or that complications may have been consider so minor as to be 'worth' reporting. In case of complications that may be experienced at home and there are significant barriers to access medical care, it is conceivable to expect that many patients will not present to health facilities for care following minor to moderate complications. Another explanation for no report of complications may be that the patients may have presented for management of complications at a different facility from where they obtained circumcision.

In virtually all the studies reviewed, the majority of complications reported were of minor clinical consequence. The exception was the study by Shittu and Shokunbi [24] which reported on a special group of patients i.e. hemophiliacs, with extremely high risk of bleeding from minimal trauma. The interpretation of prevalence of complications in this study must be made within these special circumstances. Other than the report of bleeding, no other complication was reported. It is unlikely though that bleeding was the only complication experienced; rather it would seem that this was the main focus of the study.

Reports on complications of male circumcision also differ in so far as the time after the circumcision that complications were reported i.e. early versus late complications. Yegane et al [27] for instance have reported on possible late complications of MC which include granuloma formation, penile rotation and secondary chordee [27]. In some of the studies that were reviewed in our study like that of Bailey et al [17] where patients were followed up for complications for 8 days, long term complications such as keloid formation may have been missed. Bailey et al's randomized controlled study however was of much longer duration and the assessment of long term complications was possible, but not reported. In general, most of the studies we reviewed reported on bleeding and infections only. Auvert's et al study however had reported an extensive list of possible complications and included zero reporting. Of the complications reported by Auvert et al, 13 (31.7%) reported pain, excessive bleeding (15%), infection (5%), damage to penis (5%), 1 anesthetic complications and 9 complaints of problems with appearance.

The prevalence of complications of MC in North America has been reported in the range of 0.2% to 0.5% [28]. However, the true prevalence of complications is not known as ways of ascertaining these will always underestimate the true prevalence [28]. Ben Chaim et al [29] have reported on series of 19,478 male infant circumcision conducted in Israel, of which only 66 (1.3%) recorded complications. This study reported fewer complications than most of the studies we reviewed but prevalence was higher than the single study that reported no complications.

The study by Okafor et al [22] which reported no complications, had potentially 119 neonates but 17 were excluded for a variety of reasons. This could suggest that proper selected of MC candidates will be necessary to minimize complications. However, such conclusion may not be justified in the absence of data on the criteria for exclusion i.e. the selection may have or may have not influenced the prevalence of complications.

There are always concerns about the safety of MC in sub-Saharan African health systems. Mattson et al reported on the feasibility of performing MC in health facilities in Kenya. The lack of basic instruments and inadequate supplies were identified as crucial limitations in facilitating provision of safe MC in that country [30]. Ahmed [31] studied circumcision practices in Anjouan, Comoros and reported that circumcisions by trained lay people were as safe as those carried out by physicians in hospitals. Training and supervision was emphasized in this series.

The special cases of complications in haemophiliacs deserve special mention. It has been reported that the use of fibrin glue or the "diathermic knife" may prevent bleeding and transfusion with blood factors [32, 33]. These supplies will need to be considered if MC is to be scaled-up, but will increase the cost of the procedure.

It is reasonable to expect that prevalence of complications from MC in Africa is likely to be higher than in countries with well-resourced health systems. While that expectation is reasonable and perhaps will be realized, a recent publication by Archibald et al is also informative [34]. Archibald et al compared contamination of blood culture specimens at Duke Medical Center (Durham, North Carolina, United States), Kamuzu Central Hospital (Malawi) and Muhimbili National Hospital (Tanzania). Contamination of specimens at both African centers was less than 2% while it was 28% at Duke Medical Center. The expectation that developing country health systems will always perform poorly when compared to developed nation health systems may therefore not be justified.

Conclusion

The literature on prevalence of complications following male circumcision in sub-Saharan Africa is limited. Most of the complications reported have been of minor clinical consequence. Reporting practices also have been varied such that comparisons among studies with regard to age of patients, indications for circumcision, duration of follow-up of complications and categories of circumcisers are difficult. There is need to develop and encourage standardized reporting of complications of male circumcisions. We believe that the finding that there is not enough data to suggest that MC is associated with more than the 'average' risk in Africa is important as public policy discussions gain momentum as whether to scale-up provision and accessibility of the procedure to prevent HIV transmission.

References

Auvert B, Buve A, Lagarde E, Kahindo M, Chege J, Retenberg N, Musonda R, Laourou M, Akam E, Weiss HA, Study Group on the heterogeneity of HIV Epidemics in African Cities: Male circumcision and HIV infection in four cities in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2001, 15 (Suppl 4): S31-40. 10.1097/00002030-200108004-00004.

National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases: Adult male circumcision significantly reduces risk of acquiring HIV: trials in Kenya and Uganda stopped early. Press release. [http://www3.niaid.nih.gov/news/newsrelease/2006/AMC1206.htm]

Roehr B: Dramatic drop in HIV infection halts circumcision trials. BMJ. 2007, 337: 11-10.1136/bmj.39073.473634.DB.

Williams BG, Lloyd-Smith JO, Gouws E, Hankins C, Getz WM, Hargrove J, de Zoysa I, Dye C, Auvert B: The potential impact of male circumcision on HIV in sub-Saharan Africa. PLos Med. 2006, 3: e262-10.1371/journal.pmed.0030262. Published online 2006 July 11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030262.

Scott BE, Weiss HA, Viljoen JI: The acceptability of male circumcision as an HIV intervention among a rural Zulu population, KwaZulu, Natal, South Africa. AIDS Care. 2005, 17: 304-13. 10.1080/09540120412331299744.

Ngalande RC, Levy J, Kapondo CP, Bailey RC: Acceptability of male circumcision for the prevention of HIV infection in Malawi. AIDS Behav. 2006, 10: 377-85. 10.1007/s10461-006-9076-8.

Bailey RC, Muga R, Poulussen R, Abicht H: The acceptability of male circumcision to reduce HIV infections in Nyanza province, Kenya. AIDS Care. 2002, 14: 27-40. 10.1080/09540120220097919.

Westercamp N, Bailey RC: Acceptability of male circumcision for the prevention of HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: a review. AIDS Behav. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9169-4.

Mills E, Siegfried N: Cautious optimism for new HIV/AIDS prevention strategies. Lancet. 2006, 368: 1236-10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69513-5.

Selemogo M: The money issue. PLoS Med. 2006, 3: e73-10.1371/journal.pmed.0030073.

Glass M: Rubbery figures. PLoS Med. 2006, 3: e70-10.1371/journal.pmed.0030070.

Siegfried N: Does male circumcision prevent HIV infection?. PLoS Med. 2006, 3: e393-10.1371/journal.pmed.0030393.

Vines J: Major potential confounder not addressed. PLoS Med. 2006, 3: e63-10.1371/journal.pmed.0030063.

Potterat JJ, Brewer DD, Muth SQ, Brody S: The protective effect of male circumcision as a faith lift for the troubled paradign of HIV epidemiology in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS Med. 2006, 3: e64-10.1371/journal.pmed.0030064.

Kahn JK, Marseille E, Auvert B: Cost effectiveness of male circumcision for HIV prevention in a South African setting. PLoS Med. 2006, 3: e517-10.1371/journal.pmed.0030517.

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB: Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000, 283: 2008-12. 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008.

Bailey RC, Moses S, Agot K, Parker CB, Maclean I, Ndinya-Achola JO: A randomized controlled trial of male circumcision to reduce HIV incidence in Kisumu, Kenya: progress to date. XV International AIDS Conference. 2006, Abstract no. TUAC0201.

Kiwanuka N, Gray R, Serwadda D, Kigozi G, Watya S, Wawer M: Circumcision for HIV of a pilot study in Rakai, Uganda. XV International AIDS Conference. 2004, Abstract no. TuPe c4771

Okeke LI, Asinobi AA, Ikuerowo OS: Epidemiology of complications of male circumcision in Ibadan, Nigeria. BMC Uro. 2006, 6: 21-10.1186/1471-2490-6-21. Published online 2006 August 25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-6-21

Auvert B, Taljaard D, Lagarde L, Sobngwi-Tambekou J, Sitta R, Puren A: Randomized, Controlled Intervention Trial of Male Circumcision for Reduction of HIV Infection Risk: The ANRS 1265 Trial. PLoS Med. 2005, 2 (11): e298-10.1371/journal.pmed.0020298. Published online 2005 October 25. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020298.

Krieger JN, Bailey RC, Opeya J, Ayieko B, Opiyo F, Agot K, Parker C, Ndinya-Achola JO, Magoha GA, Moses S: Adult male circumcision: results of a standardized procedure in Kisumu district, Kenya. BJU International. 2005, 96: 1109-1113. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05810.x.

Okafor PLS, Orakwe JC, Osuigwe AN, Chianakwana GU: Experience with immediate post-partum circumcision. Nigerian Medical Practitioner. 2005, 47: 9-11.

Osuigwe AN, Ikechebelu JI, Okafor PIS: Circumcision-related complications in the male: experience among the Igbos of Southeast Nigeria. African Journal of Urology. 2004, 10: 246-51.

Shittu OB, Shokunbi WA: Circumcision in hemophiliacs: the Nigerian experience. Hemophilia. 2001, 7: 534-6. 10.1046/j.1365-2516.2001.0537b.x.

Manji KP: Circumcision of the young infant in a developing country using the Pastibell™. Annals of Trop Paediatr. 2000, 20: 101-04.

Magoha GAO: Circumcision in various Nigerian and Kenyan Hospitals. East Afr Med J. 1999, 76: 583-86.

Yegane RA, Kheirollahi AR, Salehi NA, Bashashati M, Koshdel JA, Ahmadi M: Late complications of circumcision in Iran. Pediatr Surg Int. 2006, 22: 442-5. 10.1007/s00383-006-1672-1.

Rose VL: AAP updates its recommendations on circumcision. American Academy of Pediatrics. Am Fam Physician. 1999, 59: 2918, 2923-

Ben Chaim J, Levin PM, Binyamin J, Hardak B, Ben-Meir D, Mor Y: Complications of circumcision in Israel: a one year multi-center survey. Isr Med Assoc J. 2005, 7: 368-70.

Mattson CL, Muga R, Poulussen R, Onyango T, Bailey RC: Feasibility of medical male circumcision in Nyanza Province, Kenya. East Afr Med J. 2004, 81: 320-35.

Ahmed A: Circumcision practice in Anjouan. Trop Doct. 2000, 30: 52-53.

Karaman MI, Zulfikar B, Caskurlu T, Ergenekon E: Circumcision in haemophiliacs: a cost effective method using a novel device. J Pediatr Surg. 2004, 39: 1562-4. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.06.025.

Avanoglu A, Çelik A, Ulman IJ, Özcan C, Kavakli K, Nisli G, Gokdemir A: Safer circumcision in patients with haemophilia: the use of fibrin glue for local haemostasis. BJU Int. 1999, 83: 91-4. 10.1046/j.1464-410X.1999.00909.x.

Archibald LK, Pallangyo K, Kazembe P, Barth Reller LB: Blood culture contamination in Tanzania, Malawi, and the United States: a microbiological tale of three cities. J Clin Microbiol. 2006, 44: 4425-29. 10.1128/JCM.01215-06.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2490/7/4/prepub

Acknowledgements

ASM is supported by a Fogarty International Center training grant to the University of North-Carolina at Chapel Hill. We thank African Journals Online for making available electronic copies of articles indexed in their data base.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

ASM conceived the idea of the study, participated in identifying papers for review and drafting of manuscript. ASM is guarantor of manuscript.

HWP participated in identifying papers for review, analysis and drafting of manuscript. RM participated in identifying papers for review and drafting of manuscript.

JII participated in identifying papers for review, analysis and drafting of manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript submitted.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Muula, A.S., Prozesky, H.W., Mataya, R.H. et al. Prevalence of complications of male circumcision in Anglophone Africa: a systematic review. BMC Urol 7, 4 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2490-7-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2490-7-4