Abstract

Background

Typical symptoms and signs of a clinical condition may be absent in spinal cord injury (SCI) patients.

Case presentation

A male with paraplegia was passing urine through penile sheath for 35 years, when he developed urinary infections. There was no history of haematuria. Intravenous urography showed bilateral hydronephrosis. The significance of abnormal outline of bladder was not appreciated. As there was large residual urine, he was advised intermittent catheterisation. Serum urea: 3.5 mmol/L; creatinine: 77 umol/L. A year later, serum urea: 36.8 mmol/l; creatinine: 632 umol/l; white cell count: 22.2; neutrophils: 18.88. Ultrasound: bilateral hydronephrosis. Bilateral nephrostomy was performed. Subsequently, blood tests showed: Urea: 14.2 mmol/l; Creatinine: 251 umol/l; Adjusted Calcium: 3.28 mmol/l; Parathyroid hormone: < 0.7 pmol/l (1.1 – 6.9); Parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP): 2.3 pmol/l (0.7 – 1.8). Ultrasound scan of urinary bladder showed mixed echogenicity, which was diagnosed as debris. CT of pelvis was interpreted as vesical abscess. Urine cytology: Transitional cells showing mild atypia. Bladder biopsy: Inflamed mucosa lined by normal urothelial cells.

A repeat ultrasound scan demonstrated a tumour arising from right lateral wall; biopsy revealed squamous cell carcinoma. In view of persistently high white cell count and high calcium level, immunohistochemistry for G-CSF and PTHrP was performed. Dense staining of tumour cells for G-CSF and faintly positive staining for C-terminal PTHrP were observed. This patient expired about five months later.

Conclusion

This case demonstrates how delay in diagnosis of bladder cancer could occur in a SCI patient due to absence of characteristic symptoms and signs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In the patients with spinal cord injury (SCI), diagnosis of a clinical condition may be delayed because these patients do not manifest traditional symptoms and signs. For example, the symptoms and signs of hydronephrosis due to urinary calculus may be bizarre and non-specific in SCI patients. [1]. In a tetraplegic patient, pyonephrosis with perinephric abscess was detected only during autopsy. [1]. We experienced problems in early diagnosis of bladder cancer in a SCI patient due to difficulties in interpretation of intravenous urography, ultrasound scan of urinary bladder and CT of pelvis, and failure to recognise the significance of persistently high white cell count and elevated C-reactive protein.

Bladder cancer may very rarely produce granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF). [2–9]. Kawanishi and associates [9] described a 84-year-old male with bladder cancer in whom, the white cell count was 46,900/mm3 in the peripheral blood and G-CSF was 226 pg/ml (normal: 30 pg/ml). The leucocyte count in the peripheral blood returned to the normal range after resection of the tumour (partial cystectomy). But leucocytosis recurred one month post-operatively and CT scan revealed intrapelvic tumour recurrence.

Bladder cancer has been shown to produce parathyroid hormone related protein (PTHrP), albeit very rarely. [10, 11]. Simultaneous production of both G-CSF and PTHrP is extremely uncommon. [12–14]. The gene encoding G-CSF and PTHrP is in the long arm of chromosome 17 and the short arm of chromosome 12, respectively. [12]. It is possible that there might be a specific abnormality in these chromosomes for simultaneous production of G-CSF and PTHrP.

We report a SCI patient who presented with recurrent urinary infection. The white cell count was high and calcium level in peripheral blood was raised. Bladder tumour was discovered and immunohistochemistry revealed positive immunostaining for G-CSF and PTHrP.

We believe that this case represents the first report of bladder cancer in a SCI patient with simultaneous production of G-CSF and PTHrP.

Case presentation

This male patient sustained complete traumatic paraplegia below T-5, at the age of six years when he was run over by a car in June 1965. He had penile sheath drainage. Intravenous urography (10/11/1994) showed normal kidneys, pelvicalyceal systems and ureters. There was a bladder diverticulum on the left side. He was doing well for 35 years. Then he started getting recurrent urinary infection. There was no history of passing blood in urine. Intravenous urography (24/07/2000) showed bilateral hydronephrosis, and hydroureter, more marked on the right side. The bladder outline was noted to be abnormal. (Figure 1). Since large amount of residual urine resulted in dilution of the contrast in the urinary bladder, further diagnostic information could not be obtained. This patient was advised to perform intermittent catheterisation in order to achieve complete, low-pressure emptying of urinary bladder. Serum urea was 3.5 mmol/L; creatinine: 77 umol/L. The significance of abnormal outline of the right side of the urinary bladder was not fully appreciated at that time.

A follow-up intravenous urography (23/10/2000) showed normal left kidney and ureter. But there was no excretion of contrast by the right kidney. Neither ultrasound scan of urinary bladder, nor cystoscopy, was performed at this stage. A MAG-3 renogram was requested to assess differential kidney function. MAG 3 renogram, which was performed on 18/06/2001, showed evidence of a cold area presumably corresponding to the right hydronephrotic kidney. Very little function was demonstrated in the left renal area. The nuclear medicine physician alerted that the patient had renal failure. On 18 June 2001, serum urea was 36.8 mmol/L; creatinine: 632 umol/L. Results of blood tests (urea, creatinine, calcium, C-reactive protein, white cell count, neutrophils, and adjusted calcium) from 03/07/2000 to 28/11/2001, are shown in seven charts in additional file 1.

Bilateral percutaneous right nephrostomy was performed. Following nephrostomy drainage, blood tests showed: Urea: 14.2 mmol/l; Creatinine: 251 umol/l; Calcium: 2.92 mmol/l; Adjusted Calcium: 3.28 mmol/l; Parathyroid hormone: < 0.7 pmol/l (1.1 – 6.9); PTHrP: 2.3 pmol/l (0.7 – 1.8).

Ultrasound scan of urinary bladder (29/06/2001) showed mixed echogenicity in bladder and the presence of debris or turbid urine was suspected; impression was chronic infection. Chest X-ray showed clear lungs. Urinary cytology (05/07/2001) revealed occasional small clusters of transitional cells and these showed mild atypia consistent with regenerative or inflammatory atypia. (Figure 2). The appearances were predominantly those of a purulent bladder washout with occasional mildly atypical epithelial cells probably representing no more than inflammation or regeneration and there was no convincing evidence of neoplasia.

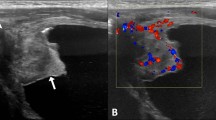

Cystoscopy was performed and biopsy was taken on 05/07/2001. Histology showed moderately inflamed transitional cell mucosa including one or two small papillary processes, which were lined by normal urothelial cells. There was no cytological atypia and no evidence of squamous carcinoma. A CT of pelvis showed a 10 × 6 cm "lesion" within the urinary bladder containing pockets of air; appearances were those of inflammatory process with abscess formation. Bone scan showed dislocation of left hip; avascular necrosis of right humeral head; no osseous metastases. A repeat ultrasound scan of urinary bladder (04/07/2001) demonstrated an 8 × 6 cm diameter tumour arising from the floor and right lateral wall, which on colour Doppler imaging was seen to be moderately vascular. (Figure 3). Transurethral resection was attempted on 27/07/2001. But it was not successful due to bleeding and consequent poor visibility. The bladder was fixed. Therefore, suprapubic cystostomy was performed. The bladder contained necrotic tumour. Debulking was done.

Histopathology revealed necrotic, keratinising, invasive, moderately differentiated, squamous carcinoma of the bladder. (Figure 4). Where present, the overlying intact epithelium showed squamous metaplasia, with dysplasia up to and including squamous carcinoma in situ. The small amount of identifiable muscle present was infiltrated by tumour, which was therefore, at least stage pT2a, and almost certainly pT2b or worse.

He developed a fistula at the site of suprapubic cystostomy. This patient received intravenous infusion of 60 mg of disodium pamidronate at periodic intervals to control hypercalcemia. He was not considered suitable for radiotherapy or chemotherapy. He had a progressive downhill course and expired about five months after bladder cancer was diagnosed.

Immunohistochemistry for G-CSF and PTHrP

In view of persistently high white cell count and high calcium level, immunohistochemistry of tumour tissue for both G-CSF and PTHrP was performed independently in two reputed laboratories. Experienced pathologists of international standing interpreted the slides of immuno-staining, and they were unaware of each other's findings.

An immunohistochemical examination of tumour biopsy for both G-CSF and PTHrP was done in Kidney Disease Centre, Saitama Medical School, 38 Morohongo, Moroyamamachi, Iruma, Saitama 3500495, Japan, on paraffin-embedded thin sections. Anti human C-PTHrP sheep serum (109–141, provided by Daiichi Radioisotope Laboratories Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and anti-human G-CSF rabbit serum (provided by Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) were used as primary antibodies. Biotin-rabbit anti sheep IgG (Zymed Laboratories, Inc., CA, U.S.A.), and ENVISION Polymer (peroxidase labelled polymer conjugated to anti-mouse and anti-rabbit Immunoglobulins, DAKO, CA, U.S.A.) served as second antibodies, respectively. The sections were subjected to immunostaining using a Histofine DAB substrate kit (Nichirei Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

Immunohistochemistry for both G-CSF and PTHrP were carried out on formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded, thin sections of tumour biopsy in the Department of Pathology, Saiseikai Central Hospital, Minatoku, Tokyo, Japan, with the following antibodies. The antibody for PTHrP was purchased from the Biogenesis Ltd. England, U.K. (Catalogue number 7170–9208). Anti rG-CSF rabbit polyclonal antibody (Lot number V-1-9) was obtained from the Chugai Pharmaceutical Company, Tokyo, Japan. The scientists in both laboratories were not aware that immunohistochemistry for G-CSF and PTHrP were being carried out in another laboratory for confirmation.

Thus two laboratories carried out immunohistochemistry for both G-CSF and PTHrP, and the results of immunostaining for G-CSF and PTHrP were consistent. G-CSF was distributed in the major population of neoplastic cells. Figure 5 represents immuno-histochemistry for G-CSF, which was carried out in the Kidney Disease Centre, Saitama Medical School, 38 Morohongo, Moroyamamachi, Iruma, Saitama 3500495, Japan. Figure 6 shows immuno-histochemistry for G-CSF, which was performed in Department of Pathology, Saiseikai Central Hospital, Minatoku, Tokyo, Japan.

Immunohistochemistry for PTHrP showed positive immunostaining for C-terminal PTHrP in the tumour cells, albeit less dense than G-CSF. Figure 7 shows immuno-histochemistry for PTHrP, which was carried out in the Kidney Disease Centre, Saitama Medical School, 38 Morohongo, Moroyamamachi, Iruma, Saitama 3500495, Japan. Figure 8 represents immuno-histochemistry for PTHrP, which was performed in Department of Pathology, Saiseikai Central Hospital, Minatoku, Tokyo, Japan.

Estimation of G-CSF and interleukin-8 (IL-8) in blood

Since this patient had elevated white cell count, G-CSF and IL-8 were estimated in blood on two occasions. Seven ml of blood was taken in a gel-free heparinised tube for estimation of G-CSF, and IL-8. Plasma was separated in a refrigerated centrifuge. The plasma sample was stored at -20 degrees Celsius and transported within 72 hours on dry ice to Division of Immunobiology, National Institute for Biological Standards and Control, Blanche Lane, South Mimms, Potters Bar, England. IL-8 levels in the plasma were estimated using an ELISA as described previously [15]. G-CSF was measured by bioassay using the GNFS-60 cell-line[16].

Results of bioassay for G-CSF and ELISA for IL-8 revealed that the plasma levels of G-CSF and IL-8 were below detectable limits.

Discussion

Receptors of G-CSF have been confirmed on the cell surfaces of several non-haematopoietic cell types, including bladder cancer cells. Tachibana and associates determined the expression of receptors of granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSFR) in five different human bladder cancer cell lines and 26 primary bladder cancers. Three, out of the five cultured cell lines, exhibited G-CSFR mRNA signals when the reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) method was used. With in situ RT-PCR, the tumour cells of 6 out of 26 primary bladder tumour specimens (23.1%) presented positive G-CSFR mRNA signals [17].

G-CSF produced by non-haematopoietic malignant cells has been reported to be capable of inducing a leukemoid reaction in the host through intense stimulation of leucocyte production. This is illustrated by the case of a 76-year-old man who had a metastatic transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder and who demonstrated marked leucocytosis, his peripheral blood leucocyte count was 94,900 leucocytes/mm3, his serum G-CSF level was 103 pg/ml. The culture medium in which the cancer cells were grown exclusively contained a significant amount of G-CSF (5560 pg/ml) [18]. G-CSF production in human bladder cancer is most frequently associated with aggressive tumour cell growth and a poor clinical outcome. [19]. Sadly, poor prognosis of C-GSF-producing bladder tumour became true in our patient. The bladder cancer showed positive immunostaining for G-CSF, and he died about five months after bladder cancer was diagnosed.

What did we learn from this case?

1. The cardinal symptom of vesical malignancy is haematuria. But this typical feature of bladder cancer was absent in this SCI patient. Amongst seventeen SCI patients in whom bladder cancer was detected at the Memphis Veterans Affairs Hospital during a surveillance programme for vesical malignancy, seven patients did not have haematuria. [20]. This patient did not pass blood in urine at any time. Therefore, we failed to appreciate the significance of abnormal outline of the right side of the urinary bladder and did not suspect bladder cancer in intravenous urography.

2. This SCI patient with bladder cancer presented with recurrent urinary infection. We did not perform cystoscopy during this patient's initial visits to the hospital. We have learnt lessons from this case and now we perform cystoscopy in the following categories of SCI patients:

SCI patients with abnormal bladder outline as demonstrated by ultrasound examination, or by intravenous urography.

SCI patients with hydronephrosis as demonstrated by ultrasound scan

SCI patients with unilateral non-visualisation of kidney in whom the previous intravenous urography showed normal upper tracts.

SCI patients in whom upper tract dilatation persists even after instituting a regimen of regular intermittent catheterisation.

SCI patients with recurrent urinary infection.

SCI patients who pass blood in urine

Cystoscopy to screen for squamous cell cancer of the bladder in spinal cord injured patients with chronic or recurrent urinary tract infection resulted in an earlier stage at diagnosis and appears to convey a survival advantage. [21]. But the cost effectiveness of cystoscopy in SCI patients with recurrent urinary infection needs to be assessed as recurrent urinary infection is not uncommon in SCI patients.

Typical symptoms of bladder cancer were absent in this SCI patient. This patient had elevated C-reactive protein, and persistently high white cell count. Initially, we attributed high white cell count and C-reactive protein to urinary infection and prescribed repeated courses of antibiotics. We made a wrong diagnosis of debris in ultrasound scan of the urinary bladder; we interpreted CT of pelvis as showing vesical abscess. Only when high white cell count persisted despite treatment with multiple courses of antibiotics, we realised that high white cell count could be tumour related, and then performed immunostaining of tumour tissue for G-CSF. Lo and behold, immunostaining for G-CSF was positive. Health professionals from various disciplines worked together to reach the correct diagnosis of bladder cancer producing both PTHrP and G-CSF. We learn that a joint team approach in reaching a diagnosis, and in implementing a treatment regime, is likely to reduce delays in diagnosis and improve the quality of care of SCI patients [22].

References

Vaidyanathan S, Singh G, Soni BM, Hughes P, Watt JW, Dundas S, Sett P, Parsons KF: Silent hydronephrosis/pyonephrosis due to upper urinary tract calculi in spinal cord injury patients. Spinal Cord. 2000, 38: 661-668. 10.1038/sj.sc.3101053.

Otani N, Kumamoto Y, Tsukamoto T, Satoh T, Sakauchi F: Bladder carcinoma producing granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Urol Int. 1994, 52: 115-117.

Akiyama A, Ohkubo Y, Hokoishi F, Ito T, Tsuchiya A, Kusama H: Bladder carcinoma producing granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF). A case report. Nippon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi. 1994, 85: 1135-1138.

Nishimura K, Higashino M, Hara T, Oka T: Bladder cancer producing granulocyte colony-stimulating factor: a case report. Int J Urol. 1996, 3: 152-154.

Nemoto R, Nakamura I, Oshika Y, Nakamura M: Transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder producing granulocyte colony-stimulating factor: a case report of molecular diagnosis. Br J Urol. 1996, 78: 653-654. 10.1046/j.1464-410X.1996.21234.x.

Ito S, Iwai Y, Fujii T, Yoshida N, Hayashi S: Two cases of bladder tumor producing granulocyte colony stimulating factor. Hinyokika Kiyo. 1999, 45: 57-60.

Iwata T, Araki H, Kushima R, Date S, Tanaka S: A case of bladder tumor producing granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Hinyokika Kiyo. 1999, 45: 847-850.

Kajio K, Hasegawa Y, Ihara K, Harada S, Kawauchi S, Fukuda T, Naito S: Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor producing undifferentiated carcinoma of urinary bladder: a case report. Nippon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi. 2000, 91: 679-682.

Kawanishi H, Aoyama T, Yoshida T, Sasaki M, Itoh T: Bladder carcinoma producing granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF): a case report. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2001, 47: 429-432.

Yoshida T, Suzumiya J, Katakami H, Kimura N, Hisano S, Kikuchi M, Okumura M: Hypercalcemia caused by PTH-rP associated with lung metastasis from urinary bladder carcinoma: an autopsied case. Intern Med. 1994, 33: 673-676.

Maeda Y, Nakazawa H, Yoshimura N, Okuda H, Oshima T, Ito F, Onitsuka S, Kihara T, Goya N, Toma H: Bladder carcinoma presenting with hypercalcemia: a case report. Hinyokika Kiyo. 1997, 43: 137-140.

Kamai T, Arai G, Takagi K, Kamai T, Arai G, Takagi K: Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and parathyroid hormone related protein producing bladder cancer. J Urol. 1999, 161: 1565-1566. 10.1097/00005392-199905000-00044.

Ueno M, Ban S, Ohigashi T, Nakanoma T, Nonaka S, Hirata R, Iida M, Deguchi N: Simultaneous production of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and parathyroid hormone-related protein in bladder cancer. Int J Urol. 2000, 7: 72-75. 10.1046/j.1442-2042.2000.00141.x.

McRae SN, Gilbert R, Deamant FD, Reese JH: Poorly differentiated carcinoma of bladder producing granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and parathyroid hormone related protein. J Urol. 2001, 165: 527-528. 10.1097/00005392-200102000-00049.

Wadhwa M, Seghatchian MJ, Lubenko A, Contreras M, Dilger P, Bird C, Thorpe R: Cytokine levels in platelet concentrates: quantitation by bioassays and immunoassays. British Journal of Haematology. 1996, 93: 225-234. 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1996.4611002.x.

Wadhwa M, Bird C, Dilger P, Mire-Sluis AR, Thorpe R: Quantitative biological assays for cytokines. In: Cytokine Cell Biology – A Practical Approach. Edited by: FR Balkwill. 2000, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 207-239. 3

Tachibana M, Miyakawa A, Uchida A, Murai M, Eguchi K, Nakamura K, Kubo A, Hata JI: Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor expression on human transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Br J Cancer. 1997, 75: 1489-1496.

Tachibana M, Miyakawa A, Tazaki H, Nakamura K, Kubo A, Hata J, Nishi T, Amano Y: Autocrine growth of transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder induced by granulocyte-colony stimulating factor. Cancer Res. 1995, 55: 3438-3443.

Tachibana M, Murai M: G-CSF production in human bladder cancer and its ability to promote autocrine growth: a review. Cytokines Cell Mol Ther. 1998, 4: 113-120.

Delnay KM, Stonehill WH, Goldman H, Jukkola AF, Dmochowski RR: Bladder histological changes associated with chronic indwelling urinary catheter. J Urol. 1999, 161: 1106-1108. 10.1097/00005392-199904000-00013.

Navon JD, Soliman H, Khonsari F, Ahlering T: Screening cystoscopy and survival of spinal cord injured patients with squamous cell cancer of the bladder. J Urol. 1997, 157: 2109-2111. 10.1097/00005392-199706000-00020.

Vaidyanathan S, Hughes PL, Soni BM, Singh G, Mansour P, Sett P: Unpredicted spontaneous extrusion of a renal calculus in an adult male with spina bifida and paraplegia: report of a misdiagnosis. Measures to be taken to reduce urological errors in spinal cord injury patients. BMC Urology. 2001, 1: 3-10.1186/1471-2490-1-3.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2490/2/8/prepub

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patient's father, who kindly agreed for publication of this case in BioMed Central Urology. The authors wish to record their sincere gratitude to the patient and to his family for their help in publication of this case in BioMed Central. While he was alive, the patient permitted us to send his biopsy specimens to Japan for immunohistochemistry for PTHrP and G-CSF. The patient gave permission to take blood samples twice for PTHrP and G-CSF assay.

We wish to record our gratitude to Dr Dan Theodorescu, Department of Urology, University of Virginia Health Sciences Centre, Charlottesville, Virginia, USA and Dr Yoichi Mizutani, Department of Urology, Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, Kyoto, Japan, for their valuable comments.

The authors thank Dr Tatsuhiko Hayashi, Department of Internal Medicine, Tokyo Saiseikai Central Hospital, 1-4-17 Mita, Minato-Ku, Tokyo 108-0073, Japan, for his valuable help in immunohistochemistry.

The authors thank AstraZeneca (Ms Charlotte Lawledge), Pharmacia (Ms Joanne Thomas), and Shire Pharmaceuticals (Mr Patrick Tierney) for financial support, which enabled the Regional Spinal Injuries Centre, Southport, UK to become an institutional member of BioMed Central.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared

Authors' contribution

SV managed the patient in the clinic, proposed that the tumour was probably producing G-CSF and PTHrP, arranged various tests, obtained consent from the patient and subsequently from the patient's father, and wrote the manuscript. PM interpreted histopathology slides of bladder biopsies. MU and KY performed immunohistochemistry for G-CSF and PTHrP independently in two separate laboratories. MW carried out G-CSF and interleukin-8 assay. PH supervised interpretation of intravenous urography, and performed colour Doppler imaging. GS performed cystoscopy and bladder biopsies. BMS was the consultant in charge of the patient. IW supervised initial processing of blood samples for PTHrP and G-CSF assay, and interpreted blood biochemistry results. All authors contributed to the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12894_2002_11_MOESM1_ESM.xls

Additional file 1: Urea, Creatinine, Calcium, C-reactive protein, White Cell Count, Neutrophils, Adjusted Calcium; Results of blood tests from 03 July 2000 to 28 November 2001. (XLS 81 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Vaidyanathan, S., Mansour, P., Ueno, M. et al. Problems in early diagnosis of bladder cancer in a spinal cord injury patient: Report of a case of simultaneous production of granulocyte colony stimulating factor and parathyroid hormone-related protein by squamous cell carcinoma of urinary bladder. BMC Urol 2, 8 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2490-2-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2490-2-8